Abstract

Background

It is important to understand donor return behavior. Converting first time donors to become repeat donors is essential for maintaining an adequate blood supply.

Methods

Characteristics of 241,552 whole blood (WB) donations from first time (FT) and repeat (RPT) donors who donated in 2008 at the 5 blood centers in China were compared. A subset of 54,394 WB donors who donated between January 1 and March 31, 2008 were analyzed for their return behavior in 2008 following the index donation using logistic regression.

Results

Of all donations, 64% was from FT donors. Donors with self-reported previous donations tended to be male, older, married, donated larger volume (≥300mL), and were heavier in weight. Among donors who donated from January to March, 2008, 14% returned for subsequent WB donations by the end of 2008. The number of previous donations and blood collection location were the two strongest predictors for making subsequent donations. Donors with 1, 2–3 and more than 3 previous donations were 3.7, 5.7, and 11.0 times more likely to return than FT donors. Those who donated in a blood collection vehicle were 4 times more likely to return than those who donated at a blood center. Being female, younger and of a lower education level (≤ middle school) were positively associated with subsequent return blood donation during the follow-up period observed in this study.

Conclusion

Most of the Chinese blood supply is from first time donors. Strategies aimed at encouraging current donors to become repeat donors are needed.

Keywords: first time donor, repeat donor, donor return

INTRODUCTION

Recruiting sufficient numbers of blood donors continues to be a challenge in China.1 The blood demand for transfusion continuously increases as a result of the increasing amount of surgeries being performed. Local areas which have high demand for blood often suffer from blood shortages. For example, in Beijing, the transfusion volume has increased by 161%, from 268 000 units (200 mL per unit) in 1998 to 700 000 units in 2008, of which 70% was for patients undergoing surgery.2 The increasing epidemic of HIV and high incidence of Hepatitis increase the threat to the blood supply,2,3 thus reducing the amount of blood available for transfusion. Furthermore, blood reserves are sometimes in short supply due to large disasters and emergency events. After large natural disasters such as the 2008 Sichuan earthquake,4 many new donors gave blood in response to the crisis. However, it is doubtful that many of these donors will donate again in the future. Experience from the U.S. has shown that recruiting strategies aimed at encouraging current donors to return for regular donations are essential for maintaining an adequate blood supply.5,6 Repeat donors have consistently been shown to have a lower transfusion-transmissible infection (TTI) risk and lower unreported deferrable risks (UDRs) than first time donors both in China and worldwide.7–10 Moreover, attracting donors with a previous donation experience for repeat donation may be more cost-effective than attracting those who have never donated.11

Many donors do not donate on a regular basis. An analysis of first time donors from January 2003 to January 2008 in the American Red Cross Blood Services system showed 39% of donors returned over 13 months, and 45% returned over 25 months; the return rate of donors aged 18–59 was much lower than donors aged 16–17.12 Studies on donor return showed that donors are more likely to donate regularly if they return soon after their initial donation,6,13 and if they have a larger number of prior donation.13–15 Schreiber et al. concluded that strategies aimed at encouraging current donors to donate more frequently during the first year may help to establish regular donation behavior.6 However the Chinese National Blood Donor Law requires a minimal interval of six months between two Whole Blood (WB) donations from the same donor, although in practice, the minimal interval could be cut down to four months if the donation is only 200mL. A longer required minimal donation interval may reduce the likelihood of a new donor becoming a regular donor. Demographic factors such as age at first donation, gender, and education level have also been hypothesized to be associated with repeat donation.6,13,14 While understanding donor return behavior is essential for designing recruitment strategies, data on Chinese donors’ return behavior is lacking.

This study describes the demographic characteristics of first time and repeat WB donations from January to December 2008 from the five blood centers collaborating in the REDS-II study. We also examine demographic and donation characteristics associated with donor return behavior in donors who made WB donations from January to March in 2008 at five blood centers that are geographically and ethnically diverse.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study (REDS-II China) is part of the Retrovirus Epidemiology Donor Study-II (REDS-II) International Program. REDS-II China is funded by the U.S. National Heart Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), and is a collaboration between The Johns Hopkins University and five Chinese blood centers: Yunnan Kunming Blood Center (Kunming, Yunnan), Urumqi Blood Center (Urumqi, Xinjiang), Luoyang Blood Center (Luoyang, Henan), Mianyang Blood Center (Mianyang, Sichuan), and Liuzhou Blood Center (Liuzhou, Guangxi). The Chinese Institute of Blood Transfusion (IBT) (Chengdu, Sichuan) serves as the in-country Study Coordinating Center providing day-to-day project oversight. Westat, Inc (Rockville, MD) serves as the Data Coordinating Center for REDS-II International. FEI.com. Inc. (Hanover, MD) provides IT technical support for the data collection and transfer of study data from the blood centers to the REDS-II Data Coordinating Center. The annual collections from the five REDS-II China blood centers are approximately 3% of China’s total donation volume. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards at all participating institutions.

Donor Database

At the time of donation, all donors fill out a pre-donation questionnaire which includes basic donor demographic, donation characteristics and health information. These pre-donation questionnaires vary across the participating blood centers, but all contain the required screening fields as mandated by the Chinese Ministry of Health. The blood center staff routinely enters the donor and donation data into their operational databases, each with varying formats and levels of complexity. On a monthly basis, the blood centers extract the REDS-II data fields and export them to FEI.com Inc (FEI). for compilation. These fields include donor demographic characteristics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, education level, marital status, and occupation), donation characteristics (donation date, donation type, donation volume, donation site, number of previous donations and date of last donation), physical exam results (weight, pulse, blood pressure, and body temperature), and screening test results. Additional fields that are not routinely stored in the blood centers’ operational databases (deferral data and supplemental test results) are entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet by each blood center for delivery to FEI. After data processing (to standardize coding and formatting), FEI transmits the complete dataset from the five blood centers to Westat for data management and analysis.

Study Population

All donors who made successful WB donation(s) between January 1 and December 31, 2008 at the five blood centers were studied. Of these, a subset of 54,394 WB donors who donated between January 1 and March 31, 2008 were further studied for their return behavior in the 9 months following their index donation during January–March. All donors were between the ages of 18 and 55 as mandated by the Chinese National Blood Donor Law.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina). Allogeneic whole blood donations in 2008 were divided into two groups: donations by first time donors versus donations by repeat donors. A donor was classified as a repeat donor if the donor self-reported a previous donation(s); otherwise a donor was considered as a first time donor. Demographic and donation characteristics associated with first time and repeat donations were tabulated. In addition, donors who made WB donations from January to March 2008 were further analyzed to examine characteristics associated with donor return. Unadjusted logistic regressions were initially conducted to measure the effect of demographic characteristics (i.e., gender, age, ethnicity, education), weight, donation volume, collection site, number of previous donations, Rh type, ABO type and blood center on donor return.. We fitted the multivariate model with all the variables which were significant in the univariate analysis, and the model was re-fit until all remaining variables were statistically significant using a backward selection process. A significance level of ≤.05 was necessary for an effect to remain in the model at iteration step.

A donor was classified as a return donor if the donor made a subsequent donation by the end of 2008 following the mandatory deferral period (200 mL, 4 months; ≥300mL, 6 months) from the date of the index donation during January–March.

RESULTS

From January 1 to December 31, 2008, a total of 241,552 WB donations were collected from 226,762 donors at the five blood centers. Of the 241,552 WB donations, 64 % were donated by first time donors and 36 % were from repeat donors. In 2008, 14,784 donors in our study (7% of all donors who made WB donations) made two WB donations and 2 donors made three WB donations.

Demographic characteristics

Table 1 shows donor demographic and donation characteristics associated with first time WB donations and repeat WB donations. Fifty-nine percent of repeat donations were from males, whereas 56% of first time donations were from males. Age distribution varied substantially between donors who gave first time donations and repeat donations. Donations given by young donors, i.e. aged 25 years and younger, accounted for 63% of the total first time donations. In contrast, the same age group contributed only 40% to repeat donations. Compared to first time donations, a larger proportion of repeat donations were from donors aged 26 years and older. Donations by unmarried donors accounted for 75% of first time donations, but only 50% of repeat donations.

Table 1.

Demographic and donation characteristics of WB donations stratified by first time and repeat donations

| Donations by first time donors % |

Donations by repeat donors % |

|

|---|---|---|

| Number of donations | 153783 | 87769 |

| Male | 55.9 | 59.0 |

| Age group | ||

| <25 | 63.1 | 39.6 |

| 25 -<35 | 21.4 | 27.8 |

| 35-<45 | 12.6 | 23.9 |

| 45+ | 2.9 | 8.8 |

| Marriage Status† | ||

| Single | 74.7 | 49.8 |

| Married | 25.3 | 50.2 |

| Han Ethnicity | 85.8 | 87.5 |

| Occupation†† | ||

| Student | 31.2 | 20.9 |

| Working* | 35.8 | 46.1 |

| Other* | 32.6 | 32.1 |

| Missing | 0.4 | 1.0 |

| Education | ||

| < High school | 21.7 | 22.1 |

| High school | 18.4 | 21.2 |

| Some college | 37.8 | 37.0 |

| College and above | 21.2 | 19.1 |

| Other | 1.0 | 0.6 |

| Weight | ||

| <55kg | 34.5 | 25.5 |

| 56-65 kg | 36.3 | 32.9 |

| 66-75 kg | 18.6 | 24.1 |

| 76-85 kg | 7.8 | 12.6 |

| 86-95 kg | 2.3 | 4.0 |

| >95 kg | 0.6 | 0.9 |

| Donation site: Collection vehicle | 97.5 | 98.1 |

| Donation volume | ||

| <200 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| 200 -<300 | 27.3 | 17.7 |

| 300-<400 | 32.6 | 25.2 |

| 400 | 39.3 | 57.1 |

“Working” represents Military, Police, Government employee, Health care personnel, Commercial Services staff, Factory worker, Farming, fishing and forestry, Unemployed, Retired, and Working at home;” Other” represents other occupations not listed in “Working”.

Urumqi and Liuzhou were left out in calculating total distribution for marital status due to large “Other” and “Missing”;

Liuzhou was left out in calculating total distribution for occupation due to large “Missing”;

Most of both first time and repeat donations were made by the majority ethnic group, Han population. An analysis of the donations by the occupation of the donors found the proportion of first time donations from students to be higher than that of repeat donations (31% vs. 21%, respectively). Donations made by employed or self-employed donors constituted 46% of the repeat donations compared to 36% of first time donations. There was no effect of education level on blood donation among Chinese donors.

Repeat donors tended to weigh more than first time donors. About one third (35%) of first time donations were from donors who weighed less than 56 kg whereas one fourth (26%) of repeat donors weighed less than 56 kg. In contrast, a larger proportion of repeat donations were from donors weighing 66 kg and above.

Larger volume (400 mL) donations constituted nearly two thirds (57%) of the repeat donations but just two fifths (39%) of first time donations. Smaller volume (200− 300+ mL) donations, on the other hand, were nearly two thirds of the first time donations (60%). The vast majority of first time and repeat donations were collected at mobile blood collection vehicles. A very small proportion of the total donations were collected at blood centers. There were no differences in the distributions of ABO or Rh blood type among first time and repeat donations.

Characteristics associated with donor return

There were 54,394 donors who made their first WB donation between January and March 2008 (index donation). They were analyzed for their return behavior (Table 2). Of these, 7,625 (14%) donors returned to make subsequent WB donations in the 9 months following their index donation. After controlling for demographic and other characteristics, the number of previous donations and the blood collection location (i.e., mobile vs. center) were the two strongest predictors for making subsequent donations. Compared to first time donors, repeat donors were more likely to make subsequent donations. The likelihood of making return donations significantly increased with an increased number of previous donations. For blood collection location, donors who made their initial donations in a blood collection vehicle were 4 times more likely to make a subsequent donation than those whose baseline donation was at a blood center.

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors associated with donor return

| Unadjusted n=54,394 |

Adjusted n=54,394 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Male | 0.95 | 0.91-1.00 | 0.89 | .83-.95 |

| P=.047 | P<.0001 | |||

| Age group | ||||

| ≤25 (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| 26 -35 | 1.11 | 1.04-1.18 | 0.73 | .68-.78 |

| 36-45 | 1.61 | 1.51-1.71 | .87 | .81-.94 |

| 46+ | 2.27 | 2.07-2.49 | 1.04 | .93-1.16 |

| P<.0001 | P<.0001 | |||

| Ethnicity* | ||||

| Han (Ref) | 1.0 | |||

| Others | 0.91 | .85-.98 | ||

| Missing | .81 | .48-1.36 | ||

| P=.031 | ||||

| Education | ||||

| < High school (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| High school | 0. 98 | .91-1.06 | .89 | .83-.97 |

| Some college | 0.86 | 0.81-0.92 | 0.86 | .80-.92 |

| College and above | 0.85 | 0.79-.92 | .89 | .82-.96 |

| Missing | .67 | .50-.89 | .44 | .32-.59 |

| Other | 0.85 | .63-1.15 | .90 | .65-1.24 |

| P<.0001 | P<.0001 | |||

| Weight (kg): | ||||

| ≤55 kg (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| 56 - ≤65 kg | 1.07 | 1.00-1.14 | .93 | .86-1.00 |

| 66 - ≤75 kg | 1.25 | 1.16-1.34 | 1.0 | .91-1.09 |

| 76 - ≤85 kg | 1.37 | 1.26-1.49 | 1.0 | .89-1.12 |

| 86 - ≤95 kg | 1.34 | 1.17-1.53 | .96 | .81-1.12 |

| ≥96 kg | 1.50 | 1.17 -1.93 | 1.24 | .94-1.64 |

| Missing | .66 | .50-.89 | .61 | .45-.83 |

| P<.0001 | P<.0001 | |||

| Donation volume | ||||

| 200 -<300 (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| <200 | 0.13 | 0.02-.98 | 0.17 | 0.02-1.20 |

| 300-<400 | 1.41 | 1.31-1.51 | 1.38 | 1.19-1.60 |

| 400 | 1.88 | 1.76-2.00 | 1.37 | 1.25-1.49 |

| P<.0001 | P<.0001 | |||

| Donation site | ||||

| Blood center (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Collection vehicle | 6.19 | 4.53-8.44 | 4.16 | 3.02-5.74 |

| P<.0001 | P<.0001 | |||

|

Number of Previous donations |

||||

| 0 (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| 1 | 3.73 | 3.49-3.99 | 3.72 | 3.48-3.98 |

| 2-3 | 5.77 | 5.38-6. 17 | 5.72 | 5.32-6.14 |

| >3 | 11.29 | 10.43-12.22 | 11.01 | 10.20-12.08 |

| P<.0001 | P<.0001 | |||

| Rh typing* | ||||

| Positive (Ref) | 1.0 | |||

| Negative | 1.24 | .86-1.79 | ||

| Missing | .62 | .08-4.80 | ||

| P=.462 | ||||

| ABO typing* | ||||

| A (Ref) | 1.0 | |||

| O | 1.00 | 0.94-1.07 | ||

| B | 0.98 | 0.92-1.05 | ||

| AB | 0.90 | 0.82-.99 | ||

| Missing | .76 | .10-6.01 | ||

| P=.2303 | ||||

| Blood center | ||||

| Kunming (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Urumqi | 0.84 | .77-.91 | .98 | .83-1.16 |

| Luoyang | 1.44 | 1.35-1.54 | 1.14 | 0.97-1.35 |

| Liuzhou | 1.22 | 1.14-1.31 | 1.35 | 1.15-1.57 |

| Mianyang | 1.36 | 1.26-1.47 | 1.28 | 1.09-1.50 |

| P<.0001 | P<.0001 | |||

Variable dropped in adjusted model during backward regression

Some demographic characteristics were also associated with returning blood donors. Being female, younger, and less educated (< high school) were positively associated with a return blood donation in the 9 months following the initial donation between January and March. Donors who donated larger volumes (≥ 300 mL or 400 mL) of blood at their index donations were also more likely to return.

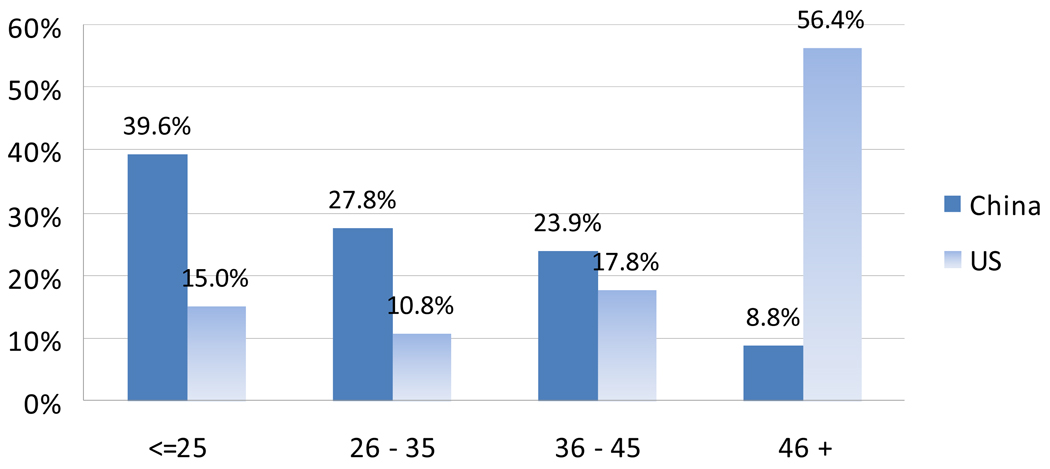

First time and repeat donations: comparison of age and gender distribution in China and the US

Age distribution

Figures 1 and 2 show the age distributions of US and Chinese donors who made first time and repeat donations in 2008. In the U.S., nearly half of the first time donations (48%) were collected from donors aged 25 years and younger whereas a reverse distribution was observed for repeat donations, such that more than half (56%) of the repeat donations were made by donors older than 46 years. This is expected since older persons are eligible to donate for a longer period of time. However this ‘reverse’ age distribution for first time and repeat donations was not seen for Chinese blood collections. In China, blood was collected predominantly from donors 25 years or younger regardless of first time/repeat donation type. Donors aged 46 and above made only a small proportion of the first time or repeat donations as compared with the US donors.

Fig. 1. Age distribution by country for repeat donations collected in 2008.

China includes 5 participating REDS-II blood centers; Yunnan Kunming Blood Center (Kunming, Yunnan), Urumqi Blood Center (Urumqi, Xinjiang), Luoyang Blood Center (Luoyang, Henan), Mianyang Blood Center (Mianyang, Sichuan), and Liuzhou Blood Center (Liuzhou, Guangxi)

U.S. includes 6 participating REDS-II blood centers; Blood Center of Wisconsin, Blood Centers of the Pacific/University of California, San Francisco, Emory University/Southern Region, American Red Cross Blood Services, Hoxworth Blood Center/University of Cincinnati Medical Center, Institute for Transfusion Medicine/LifeSource Blood Services, and New England Region, American Red Cross Blood Services

Fig. 2. Age distribution by country for first time donations collected in 2008.

China includes 5 participating REDS-II blood centers; Yunnan Kunming Blood Center (Kunming, Yunnan), Urumqi Blood Center (Urumqi, Xinjiang), Luoyang Blood Center (Luoyang, Henan), Mianyang Blood Center (Mianyang, Sichuan), and Liuzhou Blood Center (Liuzhou, Guangxi)

U.S. includes 6 participating REDS-II blood centers; Blood Center of Wisconsin, Blood Centers of the Pacific/University of California, San Francisco, Emory University/Southern Region, American Red Cross Blood Services, Hoxworth Blood Center/University of Cincinnati Medical Center, Institute for Transfusion Medicine/LifeSource Blood Services, and New England Region, American Red Cross Blood Services

Gender distribution

Overall, significantly more WB donations came from male than female donors in China in 2008 (57% vs. 43%, respectively). In contrast, in the U.S. during the same period, the proportion of WB donations were roughly equivalent for males and females (51% vs. 49%, respectively). When donations were further stratified by first time/repeat donation status, male donors in China consistently made more WB donations than female donors (56% vs. 44% in first time donors and 59% vs 41% in repeat donors). Conversely, in the U.S WB donations were not always collected more from one gender than the other (44% vs.56% in first time donors and 50% vs. 50% in repeat donors).

DISCUSSION

This study compares first time and repeat donations and examines short term donor return behavior at five Chinese regional blood centers. Compared to first time donors, repeat donors tended to be male, older (≥ 25 years), married, employed or self-employed, donated larger volume units (≥300mL) and were heavier in weight. The ratio of repeat donations to first time donations was about one to two. This was lower compared to the annual ratio of nearly four to one (78% to 22%) in the US in 2008 (Unpublished domestic REDS-II data). There were variations between blood centers. Ten percent and 4% more first time donations were collected from Kunming and Urumqi than repeat donations respectively, while more repeat than first time donations were from the other three blood centers.

Among those who donated from January to March, 2008, 14% returned for subsequent WB donations in the following 9 months. Because of the Chinese National Blood Donor Law, donors who made 200mL or ≥300mL whole blood donations are not allowed to return within four or six months, respectively; thus the eligible donation period for the study ranged between 5–7 months for donors with 200mL donations and 3–5 months for donors with ≥300mL donations. This return rate (around 20%) is comparable to the U.S. donors return rate in the first 3 months after renewed eligibility (i.e. the first 3 months after the 56 day deferral in the U.S., as compared to the first 3 months after the 6 month deferral in China (personal communication; D. Wright). Our study is limited in that the follow up time is short; however with ongoing data accumulation, we will be able to explore the donation intensity during a longer period.

Encouraging more donors to make repeat donations is key to maintaining an adequate and safe blood supply.5,6 Moreover, attracting donors who already have donation experience for regular donation may be more cost-effective than attracting those who have never donated.11 Currently, one available theory of donation behavior is that donors become habituated after three to four donations.6 Our data supported this theory in that, after adjusting for demographic and other donation characteristics, donors with more than three previous donations were 11 times more likely to return when compared to first time donors. Several studies have also confirmed that donors who give repeat donations are more likely to give future donations.11,16 Similarly, a study conducted by Zillmer et al, on donor mood states found a decrease in negative feelings about blood donation as donors returned more frequently, thus making donation a habitual process.17

Our study results are consistent with studies in developed countries; repeat donors were more likely to make return donations, and the likelihood of making return donations significantly increased with an increased number of previous donations. Perhaps the first three to four donations are the most important in conditioning donors to develop regular donation habits; thus blood centers should make special efforts to encourage donors who have recently made one or two donations to return. Active follow up may also be effective since the domestic REDS study found that a blood drive organizer/recruiter and a letter or call from the blood bank were the strongest factors influencing donation.18

Our results also showed the need for blood centers to encourage first time donors to return to donate again. Even donors with one previous donation had an odds of future return 3.7 times that of first time donors, which indicates that once donors return they are more likely to return in the future. Our findings in China are different from the U.S. in that donations were mainly from first time donors. These first time donors are potential resources to become repeat donors and deserve recruiting efforts. A study conducted by Glynn et al.18 found that first time donors were 4 times more likely to report being encouraged by family, friends, or coworkers than repeat donors. In addition, Charng, Piliavin and Callero found the number of donations was associated with social responsibility and altruistic behavior scores,19 indicating repeat donors were motivated by intrinsic factors. Therefore the recruiting strategies for first time and repeat donors should be especially tailored to reinforce their different motivations for donating blood. For first time donors, strategies such as student helper or family members sharing donation experiences with peers may be effective to attract more “curious” donors to experience the donation process. As donors become more familiar with donating, education and publication stressing donations as a socially desirable behavior and the medical need for blood may also attract repeat donors to habitually donate.

Not surprisingly, we found donors who donated at mobile collection vehicles were 4 times more likely to return than donors who donated at blood centers. Inconvenient locations were consistently cited as an important reason not to donate, especially by younger donors.16,20,21 Schreiber et al. found that not having a convenient place to donate was a significantly more important factor for donors younger than 25 years than for older donors in the US.20 In China the majority of blood donations were collected in mobile collection vehicles. Unlike the mobile collection vehicles in the U.S., mobile collection vehicles in China usually operate at same “fixed” locations in the most crowded streets of a city, where they can be accessed by more people. They also have more flexible working hours, and work on weekends to allow people to donate while shopping. Mobile collection vehicles also visit universities and colleges to facilitate student donations. As evidenced by our study, mobile collection units were an effective strategy to recruit donors; however more analysis is needed to determine if a mobile collection unit is effective in donor maintenance.

We found female, younger, lower educated, and donors donating a larger volume unit (≥300mL) were more likely to return. Since voluntary donation in China does not have a long history, it is possible that the younger generation receives different education and have a different culture than the older generation, and thus are more likely to become repeat donors in the future. However our results were based on “short-term” return behavior which was limited by the 8-month follow-up period. More studies on longer follow-up data are needed to examine if these results will remain consistent. If studies on the long-term return behavior in Chinese donors show the same results, they will be quite different from the U.S. studies which have consistently shown that older donors and donors with higher education level were more likely to become regular donors.5,6,11,22 Nguyen et al.21 found that different education groups have different motivations for donating. Unfortunately, little information is available on Chinese donors motivations and such studies are needed in order to develop targeted recruitment strategies for each donor group. Although they are deferred for a longer time, large volume donors are 1.4 times more likely to return than small volume donors. Traditionally most WB donations in China have been 200mL. In recent years, blood centers have been encouraging donors to donate larger volume WB donations (300mL or 400mL). It is possible that larger volume donors have more positive attitudes towards donation and are more willing to return.

This study happened in the same year as the 2008 Sichuan earthquake (May 12, 2008). Another paper published by our group found a significant increase in collected blood donations after the earthquake in three blood centers.23 The increase of first time donors was 2.5-fold of the repeat donors in the post earthquake week, suggesting these first time donors could be a potential pool for routine blood supply in the future. The demographic characteristics of donors in the post earthquake week were similar to those who donated during the rest of the year, suggesting the factors related to donor return were probably not affected by the earthquake.

This study has several limitations. First, we only have one year of data, and the eligible period for donors to return is limited. A donor can at most donate four times in theory if he/she donated 200mL every time and the initial donation was in January. In fact this situation was not seen in our data as most return donors donated only twice in 2008 and only two donors donated three times. Our results may therefore actually reflect only the early return rates, whereas long-term return rates may be higher. Therefore, our findings on the factors related to donor return were actually based on only one return donation, and thus may not represent the eventual overall donor return behavior. Because donors who return once are more likely to return in the future in studies of donor behaviors reported elsewhere11,18, we believe factors related to the initial return may be predictive for future multiple returns. We plan to continue our analysis of return behaviors in the future. However, these early data may be useful to develop strategies for the blood centers to increase the return donations among first time donors. Since only 5 blood centers participated in the study, they may not be representative of all blood donors in China, however, the donors at these centers were similar to the blood centers at other blood collection centers in China.

Second, the number of previous donations is self-reported data. It is possible that first time donors may have reported previous donations or repeat donors did not report previous donations. Actually we found 15 donors who donated twice in 2008, but reported no previous donations each time. Third, there is no linkage between blood centers. If a donor moves from one blood center to another, his/her donation history could not be retrieved. Fourth, we did not measure donor deferrals and were not able to estimate the proportion of donors prevented from regular donation due to health problems.

Our study shows that Chinese donors with self-reported repeat donations were more likely to give future donations.11,16 After adjusting for demographic and other donation variables, the number of previous donations is positively associated with future return, and there is a dose-response relationship. Donors who donated at mobile collection vehicles were more likely to return than those who donated in blood centers. We also found that being female, younger, less educated (<high school), and donors donating a larger volume unit (≥300mL) were more likely to return for additional donations. Future studies on long-term donor return behavior and donor motivations will help the development of improved recruitment strategies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NHLBI contract N01-HB-47175

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest relevant to the manuscript submitted to TRANSFUSION.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bay F. Why It's Really Hard to Draw Blood in China. U.S. News and World Report. 1998;125(18):44. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu X, Huang Y, Qu G, et al. Safety and current status of blood transfusion in China. The Lancet. 2010;365(9724):1420–1421. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu S, Figueroa P, Rou K, et al. Safety of the Blood Supply in a Rural Area of China. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 53 Supplement 1:S23–S26. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c7d494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang Y, Liu J, Bi X, et al. Impact of the May 12 2008 Earthquake on Blood Donations Across Five Chinese Blood Centers (abstract) Transfusion. 2009;49(3S) doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schreiber GB, Glynn SA, Damesyn M, et al. Lapsed donors: an untapped resource. Transfusion. 2003;43:17–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2003.00290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schreiber GB, Sharma UK, Wright DJ, et al. First year donation patterns predict long-term commitment for first-time donors. Vox Sanguinis. 2005;88(2):114–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2005.00593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams AE, Thomson RA, Schreiber GB, et al. Estimates of Infectious Disease Risk Factors in U.S. Blood Donors. Survey of Anesthesiology. 1998;42(3):172. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glynn SA, Kleinman SH, Schreiber GB, et al. Trends in Incidence and Prevalence of Major Transfusion-Transmissible Viral Infections in US Blood Donors, 1991 to 1996. JAMA. 2000;284(2):229–235. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zaller N, Nelson KE, Ness P, et al. Demographic characteristics and risks for transfusion-transmissible infection among blood donors in Xinjiang autonomous region, People's Republic of China. Transfusion. 2006;46(2):265–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.00711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Archer G, Buring M, Clark B, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus antibody in Sydney blood donors. Med J Aus. 1992;152:225–227. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1992.tb137122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schreiber GB, Sanchez AM, Glynn SA, Wright DJ. Increasing blood availability by changing donation patterns. Transfusion. 2003;43(5):591–597. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2003.00388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Notari EP, Zou S, Fang CT, et al. Age-related donor return patterns among first-time blood donors in the United States. Transfusion. 2009;49(10):2229–2236. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ownby HE, Kong F, Watanabe K, et al. Analysis of donor return behavior. Transfusion. 1999;39(10):1128–1135. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1999.39101128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.James R, Matthews D. Analysis of blood donor return behavior using survival regression methods. Transfus Med. 1996;6:21–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3148.1996.d01-46.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whyte G. Quantitating donor behaviour to model the effect of changes in donor management on sufficiency in the blood service. Vox Sanguinis. 1999;76:209–215. doi: 10.1159/000031053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schlumpf KS, Glynn SA, Schreiber GB, et al. Factors influencing donor return. Transfusion. 2008;48:264–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zillmer EA, Glidden RA, Honaker LM, Meyer JD. Mood states in the volunteer blood donor. Transfusion. 1989;29(1):27–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1989.29189101159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glynn S, Kleinman S, Schreiber G, et al. Motivations to donate blood: demographic comparisons. Transfusion. 2002;42(2):216–225. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2002.00008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steele WR, Schreiber GB, Guiltinan A, et al. The role of altruistic behavior, empathetic concern, and social responsibility motivation in blood donation behavior. Transfusion. 2008;48(1):43–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schreiber G, Schlumpf K, SimoneA G, et al. Convenience, the bane of our existence, and other barriers to donating. Transfusion. 2006;46(4):545–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen DD, DeVita DA, Hirschler NV, Murphy EL. Blood donor satisfaction and intention of future donation. Transfusion. 2008;48(4):742–748. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01600.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Germain M, Glynn SA, Schreiber GB, et al. Determinants of return behavior: a comparison of current and lapsed donors. Transfusion. 2007;47(10):1862–1870. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu J, Huang Y, Wang J, et al. Impact of the May 12, 2008, earthquake on blood donations across five Chinese blood centers. Transfusion. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]