Abstract

A new method for the synthesis of dihydroimidazo[1,2-a][1,3,5]triazin-4(6H)-ones via copper(I)-catalyzed hydroamination was developed. In addition, for the first time iodoalkynes were shown to participate in the copper(I)-catalyzed intramolecular hydroamination reaction with exclusive formation of E-isomers.

The unique role that purine and pyrimidine heterocycles play in biology makes them timeless subjects of research in disciplines encompassing the fields of organic synthesis, medicinal chemistry, biotechnology, and materials science.1 Small molecules containing imidazo[1,2-a]-s-triazine fragment, which is an analog of 5-aza-7-deaza-purine, have been identified as promising candidates in the treatment of Type 1 diabetes, rhinovirus infections, and against the Flaviviridae family of viruses.2 Whether the goal is the discovery of compounds with new biological function or expansion of the genetic alphabet, a methodology that allows simple and reliable access to novel purine analogs would be a valuable addition to these fields. Herein, we report a new approach toward dihydroimidazo[1,2-a][1,3,5]triazinone derivatives via a copper-catalyzed hydroamination, delivering a practical, scalable and versatile route to these rarely studied heterocycles.

The construction of imidazo[1,2-a]-s-triazine (1) core can commence from 2-aminoimidazole (2),1c;2a,b 5-azacytosine (3, X=NH2)2c,d or 1,3,5-triazine heterocycles (3, X=Cl) (Scheme 1).3a,b;2e,f However, these methodologies have not proven to be practical due to the low conversions and limited substrate scope. We envisioned assembling the imidazo[1,2-a]-s-triazine ring system via transition metal-catalyzed hydroamination of alkynyl triazinones 4,4 which are easily derived from cyanuric chloride (5).

Scheme 1.

Synthetic routes to 7-aza-5-deazapurines

First, we examined the effect of different transition metal catalysts on the intramolecular cyclization of triazine 6 as a model substrate. The results of a focused screen employing group 11 transition metals are presented in Table 1.5 Although gold(I) and silver(I) salts promoted the reaction at ambient temperature, the yields were moderate, and long reaction times were required (entries 1–2). In contrast, copper(I) salts were more active catalysts for the desired intramolecular cyclization (entries 3–11).6 The addition of water increased the yield of the reaction (cf. entries 3 and 4). The optimal results were obtained when copper(I) acetylides were generated in situ (entries 9–11).7 The addition of tris((1-benzyl-1H-1,2,3-triazolyl)methyl)amine (TBTA) ligand further improved the efficiency of the reaction (entry 11).8

Table 1.

Optimization of the reaction conditionsa

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Catalyst | Additive | Yield, %b |

| 1 | Au(PPh3)Cl[c] | AgBF4(5 mol %) | 44 |

| 2 | AgNO3[d] | - | 60 |

| 3 | [Cu(CH3CN)4]PF6[e] | - | 52 |

| 4 | [Cu(CH3CN)4]PF6 | - | 64 |

| 5 | CuOTf × ½ PhMe | - | 42 |

| 6 | CuOAc | - | 46 |

| 7 | CuI | - | 60 |

| 8 | CuTC | - | 68 |

| 9 | CuSO4 | NaAsc (20 mol %) | 70 |

| 10 | CuSO4 | NaAsc (1 equiv) | 82 |

| 11 | CuSO4 | NaAsc (20 mol %), TBTA (10 mol %) | 99 |

Conditions: 6 (0.5 mmol), 10 mol % of catalyst, CH3CN/H2O (2/1, 0.1M), 50 °C, 6h unless noted otherwise.

Isolated yield of 7.

5 mol%, DCE, rt, 48h.

20 mol%, CH3CN, rt, 48h.

CH3CN without water

A general method for the preparation of 1,3,5-triazine-2-ones (4) was then investigated. Temperature controlled sequential displacement of chlorines in 5 provides facile access to substituted 1,3,5-triazines (Scheme 2).9 However, conversion of less electrophilic intermediates, such as 8, to the corresponding 1,3,5-triazine-2-ol (10) via direct addition of hydroxide is problematic.

Scheme 2.

Cleavage of N-O bond with Cu(II)/NaAsc/O2

N,N-dialkylhydroxylamine substituted triazines (9) have been converted to the corresponding hydroxyl derivatives under acidic conditions or with prolonged heating.10 While these conditions failed to produce the desired product, treatment of 9 with CuSO4 and sodium ascorbate gave the desired 1,3,5-triazine-2-ol (10). In order to achieve good conversions, a stoichiometric amount of sodium ascorbate was employed.11

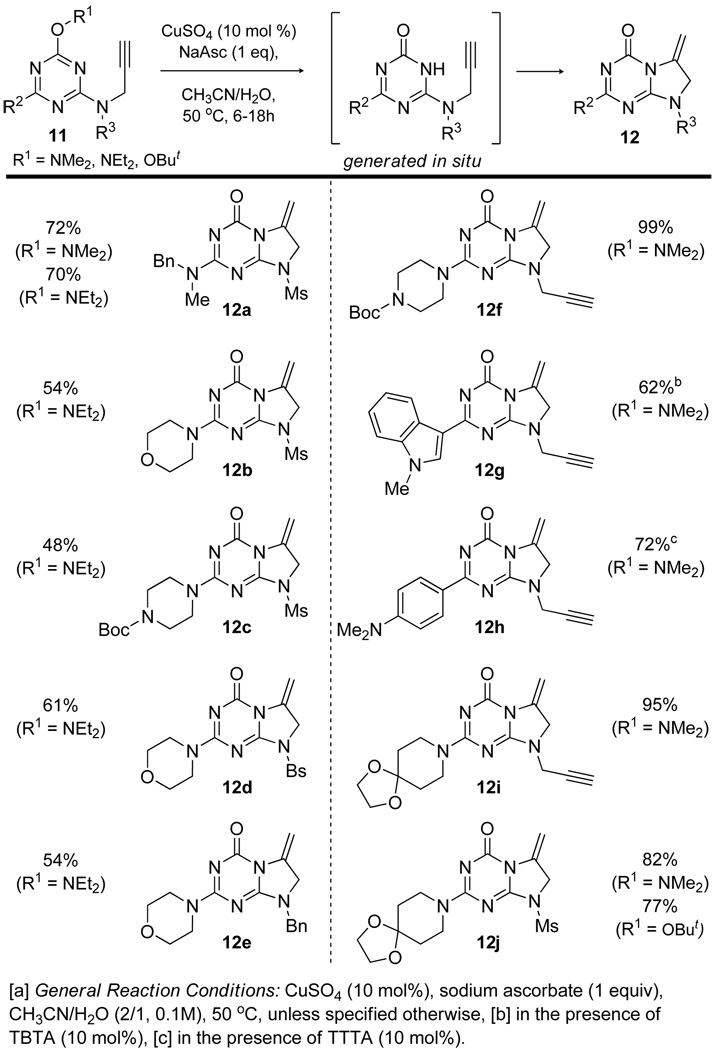

With the developed procedure in hand, the scope of the direct intramolecular hydroamination was examined (Figure 1). Both N-dimethyl and N-diethyl hydroxylamine derivatives were utilized and gave similar results (12a).12 The regiochemistry of 12a was confirmed by single crystal x-ray analysis, allowing the geometry of other cyclized products to be inferred via 1H and 13C NMR. While most substrates were easily converted to the corresponding dihydroimidazo[1,2-a][1,3,5]triazinones using the optimized conditions within 12–18 hours, cyclization to give 12g and 12h was markedly slow requiring the use of a ligand (TBTA or its analog, tris((1-tert-butyl-1H-1,2,3-triazolyl)methyl)amine, TTTA can be employed).

Figure 1.

Substrate scope for the Cu(I)-catalyzed hydroamination

1,3,5-Triazines containing NH-propargyl group (10a), or internal alkynes (10b) failed to undergo cyclization (Scheme 2). The latter result points to the activation of the alkyne via σ-copper acetylide intermediate, which was supported by the results of deuterium labeling experiment (Scheme 3). Reaction performed in deuterated solvent showed exchange of only acetylenic protons, excluding the intermediacy of allene species.

Scheme 3.

Deuterium-labeling experiment.

In principle, the acetylide intermediate can be trapped with other electrophiles in situ, for example with electrophilic iodine reagents. Our group recently reported a copper catalyzed iodination of terminal alkynes by N-iodomorpholine.13 In addition, a CuI/TTTA catalytic system was shown to activate 1-iodoalkynes toward the cycloaddition with organic azides.13 We envisioned that the same catalytic system could be employed in hydroamination of 1-iodoalkynes. Thus, several substrates were treated with N-iodomorpholine in the presence of CuI and TTTA (Figure 2) forming vinyl iodide 15 via 5-exo-dig cyclization of the transient 1-iodoalkyne. Strikingly, this process generated 15b as a single regioisomer, as confirmed by the X-ray analysis.

Figure 2.

Substrate scope for Cu(I)-catalyzed cyclization

The LC-MS analysis of the reaction mixture at different time points indicated that the observed annulation proceeds through a series of steps outlined in Scheme 4. We confirmed formation and interconversion of intermediates A, B, and C during the course of the reaction. Under the optimized reaction conditions, intermediates A and B predominate and lead to the formation of 15b. The presence of a proton source and suboptimal Cu(I)/N-iodomorpholine/substrate ratios lead to the accumulation of intermediate C and, as a result, generation of by-product 12j. Since formation of the desired product may be affected by multiple equilibria, the optimal ratio of the starting material to N-iodomorpholine is substrate dependent and needs to be optimised on a case by case basis. Regardless of the substrate, Cu(I) and TTTA are essential for the formation of vinyliodide 15b. Treatment of 11j with N-iodomorpholine for 24 h at ambient temperature in the absence of a copper catalyst gave a mixture consisting mostly of starting material and a small amount of iodoallkyne A.

Scheme 4.

Proposed sequence of steps for one-pot generation of 1-iodoalkynes and following cyclization

Thus, preliminary results suggest that Cu(I)/N-iodomorpholine system acts as a mild oxidant, and its reactivity towards alkynes is fundamentally divergent from the iodoamination reaction, which is characterized by lower chemo- and regioselectivity.14 To further support this proposal, we prepared starting material 16 and subjected it to the optimized reaction conditions and, separately, to the treatment with iodine (Scheme 5). After 18 hours at room temperature, the copper-catalyzed reaction produced exclusively 17 in 85% isolated yield, whereas reaction with iodine resulted in a complex mixture of at least four compounds.15

Scheme 5.

Comparative study of the reaction promoted by CuI/N-iodomorpholine vs. iodine

In summary, the new hydroamination protocol allowed generation of dihydroimidazo[1,2-a][1,3,5]triazinones. Further, 1-iodoalkynes were shown, for the first time, to participate in the copper(I)-catalyzed intramolecular hydroamination reaction with the exclusive formation of the E-vinyl iodides. The procedures are simple to perform, utilize inexpensive reagents and easily provide access to densely decorated purine analogs containing functional groups amenable for further derivatization.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Procedure for Intramolecular Hydroamination. Synthesis of 6-methylene-8-(methylsulfonyl)-2-(1,4-dioxa-8-azaspiro-[4.5]decan-8-yl)-7,8-dihydroimidazo-[1,2-a][1,3,5]-triazin-4(6H)-one (12j)

A reaction flask was charged with N-(4-(dimethylaminooxy)-6-(1,4-dioxa-8-azaspiro[4.5]-decan-8-yl)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)-N-(prop-2-yn-yl)-methanesulfonamide (11j) (1.50 g, 3.64 mmol), CuSO4 (365 µL, 1M, 10 mol %) and acetonitrile/water mixture (2:1, 35 mL). After addition of sodium ascorbate (0.72 g, 3.64 mmol) reaction flask was capped and heated at 50 °C for 5 hours.16 Upon completion, reaction mixture was cooled down and quenched with NH4OH/brine solution (10 mL, 1:1). Yellow crystalline precipitate was collected by filtration, washed with NH4OH/brine, water and dried in vacuo. 12j was obtained as yellow solid (1.10 g, 82% yield). mp 206 °C (dec.). 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.19 (s, 1H), 4.82 (s, 1H), 4.59 (s, 2H), 3.96 (s, 6H), 3.91 (s, 2H), 3.38 (s, 3H), 1.71 (s, 4H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 161.1, 156.1, 152.5, 132.5, 106.9, 97.8, 64.7, 48.3, 42.9, 42.8, 41.3, 35.4, 34.9. HRMS (ESI): 370.1180 (MH+) (exact 370.1180 for C14H20N5O5S).

Procedure for One-pot Generation of Iodoalkyne and Intramolecular Cyclization. Synthesis of (E)-6-(iodomethylene)-8-(methylsulfonyl)-2-(1,4-dioxa-8-azaspiro-[4.5]decan-8-yl)-7,8-dihydroimidazo[1,2-a][1,3,5]triazin-4-(6H)-one (15b)

11j (300 mg, 0.73 mmol), copper iodide (14 mg, 0.073 mmol, 10 mol%), TTTA (31 mg, 0.073 mmol, 10 mol%) and N-iodomorpholine (186 mg, 0.55 mmol) were mixed together in dry THF (7.5 mL, 0.1M). Reaction tube was flushed with N2, sealed, and stirred at room temperature for 18h. Upon completion reaction mixture was quenched with NH4Cl sat. (10 mL) and product was allowed to crystallize upon slow removal of organic solvent. Beige-yellow precipitate was collected by filtration, washed with NH4Cl sat. (10 mL), washed extensively with water and dried in vacuo to give 15b (259 mg, 96% yield). mp 200.5 °C (dec.). 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 7.11 (t, J = 2.8, 1H), 4.50 (d, J = 2.7, 2H), 3.92 (s, 4H), 3.87 – 3.82 (m, 2H), 3.82 – 3.79 (m, 2H), 3.47 (s, 3H), 1.70 – 1.62 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, D2O) δ 161.1, 156.1, 151.1, 134.8, 106.2, 63.9, 61.5, 53.4, 42.2, 42.0, 39.8, 34.6, 34.2. HRMS (ESI): 496.0140 (MH+) (exact 496.0146 for C14H19IN5O5S). Crystal suitable for the X-ray crystallographic analysis was obtained upon slow crystallization from water/DMSO mixture.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health (GM087620). We thank Prof. K. Barry Sharpless (TSRI) for helpful discussions. X-ray crystallography was performed by Dr. Arnold Rheingold and Dr. James A. Golen (UCSD).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures, compound characterization data, crystallographic information files (CIFs) and copies of 1H, 13C NMR spectra for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.a) Seela F, Melenewski A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1999:485–496. [Google Scholar]; b) Seela F, Melenewski A, Wei C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1997;7:2173–2176. [Google Scholar]; c) Rao P, Benner SA. J. Org. Chem. 2001;66:5012–5015. doi: 10.1021/jo005743h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Krueger AT, Kool ET. Chem. Biol. 2009;16:242–248. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Silverman AP, Kool ET. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:3775–3789. doi: 10.1021/cr050057+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Prisbe EJ, Verneygen JPH, Moffatt JG. J. Org. Chem. 1978;43:4774–4784. [Google Scholar]; b) Prisbe EJ, Verneygen JPH, Moffatt JG. J. Org. Chem. 1978;43:4784–4794. [Google Scholar]; c) Nair V, Lyons AG, Purdy D. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;47:8949–8968. [Google Scholar]; d) Hanami T, Oda H, Nakamura A, Urata H, Itoh M, Hayashizaki Y. ibid. 2007;48:3801–3803. [Google Scholar]; e) Balasubramanian KK, Bindumadhavan GV, Udupa MR, Krebs B. ibid. 1980;21:4731–4734. [Google Scholar]; d) Bindumadhavan GV, Balasubramanian KK. Tetrahedron. 1985;41:111–120. [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Cui P, Macdonald TL, Chen M, Nadler JL. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:3401–3405. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kim S-H, Bartholomew DG, Allen LB, Robins RK, Revankar GR, Dea P. J. Med. Chem. 1978;21:883–889. doi: 10.1021/jm00207a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ojwang JO, Ali S, Smee DF, Morrey JD, Shimasaki CD, Sidwell RW. Antiviral Res. 2005;68:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.For recent reviews on transition metal catalyzed hydramination of alkynes see: Müller TE, Hultzsch KC, Yus M, Foubelo F, Tada M. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:3795–3892. doi: 10.1021/cr0306788. Severin R, Doye S. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006;36:1407–1420. doi: 10.1039/b600981f. Widenhoefer RA, Han X. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006;(20):4555–4563.

- 5.Expanded screen of catalysts can be found in the Supporting Information section.

- 6.For a recent example of a one-pot cascade Mannich-Cu(I) promoted hydroamination of alkynes see: Wang H-F, Yang T, Xu P-F, Dixon DJ. Chemm. Comm. 2009:3916–3918. doi: 10.1039/b905629g.

- 7.Rostovtsev VV, Green LG, Fokin VV, Sharpless KB. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002;41:2596–2599. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2596::AID-ANIE2596>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan TR, Hilgraf R, Sharpless KB, Fokin VV. Org. Lett. 2004;6:2853–2855. doi: 10.1021/ol0493094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.For recent reviews on the chemistry of 1,3,5-triazines, see: Blotny G. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;62:9507–9522. Gamez P, Reedijk J. Eur. J. Inorganic Chem. 2006:29–42. Giacomelli G, Porcheddu A, de Luca L. Curr. Org. Chem. 2004;8:1497–1519.

- 10.Sanders ME, Ames MM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:5247–5250. [Google Scholar]

- 11.We are currently investigating the mechanism of this transformation; a comprehensive report will be published in due course.

- 12.tert-Butyl peroxide derivatives can be used with equal success (cf. 12j).

- 13.Hein JE, Tripp JC, Krasnova LB, Sharpless KB, Fokin VV. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:8018–8021. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noguchi M, Okada H, Watanabe M, Okuda K, Nakamura O. Tetrahedron. 1996;52:6581–6590. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Retention times and molecular ion obtained by LCMS analysis were used in structure assignment. Another major intermediate of molecular ion 498 corresponds to the addition of two iodine atoms to intermediate of general structure C (Scheme 4).

- 16.White precipitate of oxy-triazine intermediate is formed within first 30 min and gradually disappears as a reaction progresses towards 12j.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.