Abstract

Background

B-vitamins are essential for one-carbon metabolism and have been linked to colorectal cancer (CRC). Although associations with folate have frequently been studied, studies on other plasma vitamins B2, B6, and B12 and CRC are scarce or inconclusive.

Methods

Nested case-control study within the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition, including 1365 incident CRC cases and 2319 controls matched for study center, age, and sex. We measured the sum of B2 species riboflavin and flavin mononucleotide, and the sum of B6 species pyridoxal 5′-phosphate, pyridoxal, and 4-pyridoxic acid as indicators for vitamin B2 and B6 status, as well as vitamin B12 in plasma samples collected at baseline. In addition, we determined eight polymorphisms related to one-carbon metabolism. Relative risks (RRs) for CRC were estimated using conditional logistic regression, adjusted for smoking, education, physical activity, BMI, alcohol consumption, and intakes of fiber, red- and processed meat.

Results

RRs comparing highest to lowest quintile (95% confidence interval, Ptrend) were: 0.71 (0.56–0.91, 0.02) for vitamin B2, 0.68 (0.53–0.87, <0.001) for vitamin B6, and 1.02 (0.80–1.29, 0.19) for vitamin B12. The associations for vitamin B6 were stronger in males who consumed ≥ 30g alcohol/day. The polymorphisms were not associated with CRC.

Conclusions

Higher plasma concentrations of vitamins B2 and B6 are associated with a lower CRC risk.

Impact

This European population-based study is the first to indicate that vitamin B2 is inversely associated with CRC, and is in agreement to previously suggested inverse associations of vitamin B6 with CRC.

Keywords: Plasma vitamins B2, B6, and B12; genetic variants; colorectal cancer; prospective study

INTRODUCTION

The one-carbon metabolism is related to carcinogenesis because of its involvement in the synthesis of purines and pyrimidines for subsequent DNA synthesis, and in the synthesis of methionine for DNA methylation. Aberrations in DNA synthesis and DNA methylation may contribute to colorectal carcinogenesis. B-vitamins and related genetic polymorphisms are essential for the one-carbon metabolism, and may therefore be associated with colorectal cancer (CRC) (1). Among the B-vitamins, folate has been studied most extensively in relation to CRC. The majority of studies on folate intake indicate a 20% to 40% CRC risk reduction in individuals with the highest compared to the lowest intake, whereas associations between plasma concentrations of folate and CRC risk are inconsistent (1). Other B-vitamins, such as vitamins B2, B6, and B12 are also involved in the one-carbon metabolism.

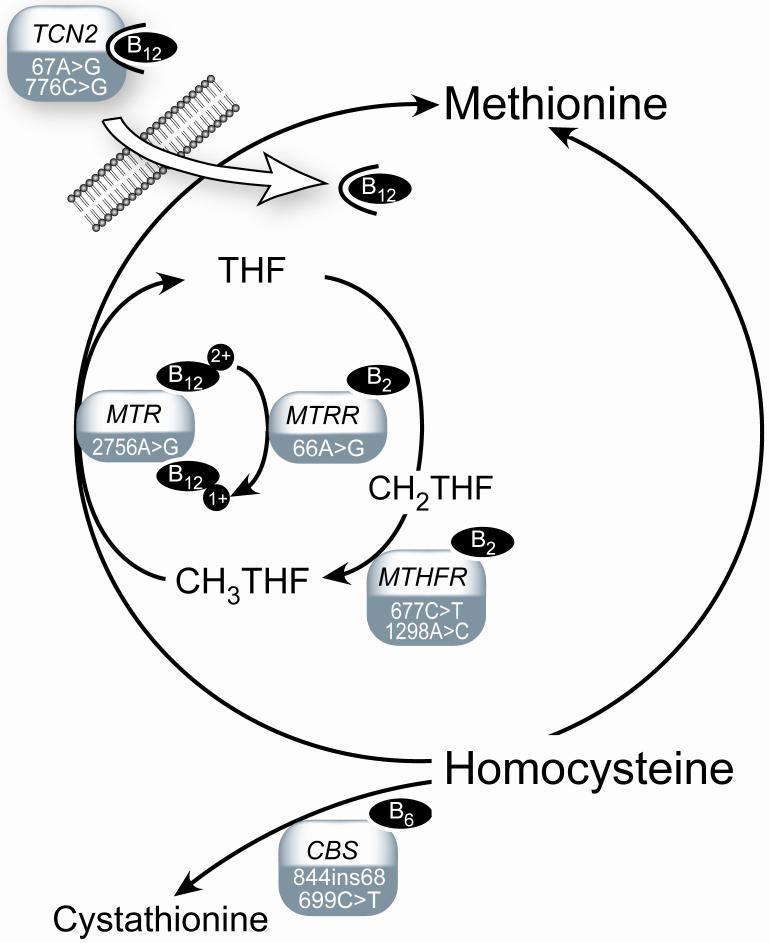

Vitamins B2 and B6 are related since the interconversion of some vitamin B6 species require the vitamin B2 forms flavin mononucleotide (FMN) and flavin dinucleotide (FAD) as cofactors (2). Moreover, vitamin B2 serves as co-factor for the methyl-metabolizing enzymes methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) which regenerates 5-methyltetrahydrofolate from tetrahydrofolate, and methionine synthase reductase (MTRR) which activates methionine synthase (MS). Vitamin B6 is cofactor for the enzyme cystathionine ß-synthase (CBS) involved in the transsulfuration pathway where homocysteine is converted into cystathionine. Vitamin B12 acts as co-factor for methionine synthase reductase (MTRR) and methionine synthase (MS), the latter catalyzing the remethylation of homocysteine to methionine. Transcobalamin II (TCN2) is essential for the uptake of vitamin B12 from the intestine (Figure 1). Suboptimal concentrations of the B-vitamin co-factors as well as related genetic polymorphisms may affect the activity of these enzymes.

FIGURE 1. One-carbon metabolism and related enzymes and genetic polymorphisms.

Cysta, cystathionine; CBS, cystathionine ß-synthase; CH2THF, methylenetetrahydrofolate; CH3THF, methyltetrahydrofolate; MTHFR, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (provision of 5-methylfolate for homocysteine remethylation); MTR, methionine synthase (remethylation of homocysteine to methionine); MTRR, methionine synthase reductase (activiation of methionine synthase); THF, tetrahydrofolate; TCN2, transcobalamin-II (vitamin B12 transport).

The majority of studies on associations of B2 (3-9) and vitamin B12 (4-14) with CRC have reported null findings. A recent meta-analysis of nine studies on vitamin B6 intake and four studies on plasma vitamin B6 concentrations revealed inverse associations with CRC risk (15). Previous research on associations between genetic variants and CRC risk has focussed mainly on MTHFR 677C→T and 1298C→A polymorphisms, which were generally inversely associated with CRC (1). In contrast, genetic variants of MTR (14, 16, 17), MTRR (4, 18, 19), CBS (4, 20-23), and TCN2 (18, 19), have been less studied in relation to CRC, and show inconsistent associations. In addition to potential interactions between B-vitamins and SNPs (24, 25), there is also some evidence for an interaction between plasma vitamin B6 and alcohol consumption (26).

Studies on plasma vitamin B2 (9), vitamin B6 (15) and plasma vitamin B12 (9, 10) concentrations and CRC risk are sparse. In addition, associations between B-vitamins and CRC risk may be modified by SNPs related to one-carbon metabolism and alcohol consumption (24, 26). Therefore, we conducted a large nested case-control study (including 1365 CRC cases and 2319 matched controls) within the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC), which is sufficiently large to address these questions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population and Collection of Blood Samples

The design and methods of EPIC have previously been described (27). Briefly, the EPIC cohort included participants from 23 centers in 10 European countries (Denmark, France, Greece, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden and United Kingdom). Between 1992 and 1998, country-specific dietary questionnaires, standardized lifestyle and personal history questionnaires plus anthropometric data were collected from all participants, and a blood samples were taken from 80% of the cohort members. Follow-up is based on population cancer registries (Denmark, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom) or through health insurance records, pathology registries, and active contact with study subjects or next of kin (France, Germany and Greece). The follow-up period for the present study was for cases included in reports received at IARC until June 2003 representing centers using cancer registry data, and until March 2004 for France, Germany and Greece.

Fasting (46%) or non-fasting (54%) blood samples of at least 30mL were drawn. B-vitamins and related metabolites did not significantly differ across fasting and non-fasting participants. Blood samples were stored at 5-10°C while protected from light and transported to local laboratories for processing and aliquoting (27). Exceptions from this procedure were the EPIC-Oxford and EPIC-Norway centers, where whole blood samples were collected through a network of general practitioners (Oxford and Norway) and health conscious people (Oxford) and transported to a central laboratory via mail. The whole blood samples were protected from light, but were exposed to ambient temperatures for up to 48 hours. As B-vitamins are partly degraded by such handling, all EPIC-Oxford (55 cases, 107 controls) and EPIC-Norway (5 cases, 9 controls) samples were excluded from the present analyses.

In all countries, except Denmark and Sweden, blood was separated into 0.5mL fractions (serum, plasma, red cells and buffy coat for DNA extraction). Each fraction was placed into straws, which were heat sealed and stored in liquid nitrogen (−196°C). One half of all aliquots were stored at local study centres and the other half in the central EPIC biorepository at the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC; Lyon, France). In Denmark, blood fraction aliquots of 1.0mL were stored locally at −150°C under nitrogen vapour. In Sweden, erythrocyte, plasma, and buffy coat samples were fractioned prior to freezing, and stored locally in −80°C freezers. This study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC; Lyon, France) and those of all EPIC centers. All EPIC participants have provided written consent for the use of their blood samples and all data.

Nested Case-Control Study Design and Selection of Study Subjects

Colon cancer was defined as tumors in the cecum, appendix, ascending colon, hepatic flexure, transverse colon, splenic flexure, descending and sigmoid colon (C18.0-C18.7 as per the 10th Revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Injury and Causes of Death), as well as tumors that were overlapping or unspecified (C18.8 and C18.9). Colorectal cancer (CRC) was defined as a combination of colon and rectal cancer. Cancers of the rectum were defined as tumors occurring at the recto-sigmoid junction (C19) or rectum (C20). The present study includes 1365 incident CRC cases (colon n=846; rectal n=519). The distribution of cases (colon/rectal) by country was (204/174) in Denmark, Sweden (100/84), France (30/3), Greece (14/13), Germany (98/61), Italy (106/43), The Netherlands (102/49), Spain (78/43), and United Kingdom (114/49).

Controls with available blood samples were randomly selected from cohort members still alive and free of cancer at the time of diagnosis of the cases. Controls were matched to cases by gender, age (±2.5 years), and study center (to account of centre specific differences in questionnaire design, blood collection procedures, etc.). An exception were Danish cases (n=378) and controls (n=373), who were post-hoc matched using the “greedy” algorithm, a macro (gmatch) provided by the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine (28, 29) to be run in SAS. The greedy algorithm sorts cases and controls randomly and the macro matches the first case with the closest available control according to specified matching criteria, which is repeated until all cases are matched. The mean (range) difference in age between cases and controls in the overall study except the Danish population, and between Danish cases and controls within each caseset was 0 (−2.4 to 1.8) and −1.03 (−5.0 to 4.9) years, respectively.

Laboratory measurements

Vitamin B2 measures included plasma concentrations of riboflavin and flavin mononucleotide (FMN), and pyridoxal’ 5-phosphate (PLP), pyridoxal (PL) and 4-pyridoxic acid (PA) were measured for vitamin B6 status. All B2 and B6 vitamers were determined by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry in the same laboratory (30). For PLP, PL ,PA and riboflavin the within- and between-day CVs were below 11%, while for FMN the CVs were 12-22%. Within- and between-day coefficients of variation for total-B2 were 7%-11% and for total-B6 3%-7%. Plasma vitamin B12 was determined by a Lactobacillus leichmannii microbiological assay (31), and plasma methylmalonic acid (MMA; inverse marker for vitamin B12 status) was measured with a method based on methylchloroformate derivatization and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (32). Vitamin B12 and MMA concentrations were analyzed in the same laboratory, with within- and between-day coefficients of variation of <5% (32). Unspiked and spiked plasma samples with unknown endogenous concentrations were used for these experiments.

Eight polymorphisms of genes encoding enzymes involved in the one-carbon metabolism were determined by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (33, 34). These included cystathionine ß-synthase (CBS 699C→T; rs234706, and the CBS 844ins68 insertion), methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR 677C→T; rs1801133 and MTHFR 1298A→C; rs1801131), methionine synthase (MTR 2756A→G; rs1805087), methionine synthase reductase (MTRR 66A→G; rs1801394), and transcobalamin II (TCN2 67A→G; rs RsaI and 776C→G; rs1801198).

Statistical Methods

Because riboflavin and FMN are interconvertable (35), as well as PLP and PL (36), and PA is formed from PL, we considered the sum of riboflavin and FMN as a measure for vitamin B2 status, and the sum of PLP, PL, and PA as a measure of vitamin B6 status. Both the summary variables as well as individual vitamin B2 and B6 species were presented. Differences in concentrations of the vitamins B2, B6, B12, and MMA between different groups were assessed by Mann Whitney U tests or χ2-tests where appropriate.

Relative risks (risk ratios (RR)) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) for CRC risk in relation to plasma B-vitamins were estimated by conditional logistic regression using the SAS LOGISTIC procedure, stratified by the case-control set. Relative risks for CRC were examined across quintiles with cut-off points based on the distribution of the B-vitamins in all 2319 controls combined. Potential confounders included smoking status (never, former, current, missing), alcohol consumption (continuous), dietary fiber (continuous), intake of red and processed meat (continuous), physical activity (inactive, moderately inactive, moderately active, active), educational level (none, primary school completed, technical/professional school, secondary school, university degree, not specified), and body mass index (BMI, kg/m2). Although none of these variables substantially altered the crude risk estimates, we present results of both the univariate and adjusted models. The adjusted models additionally adjusted for mutual B-vitamins and folate. Likelihood ratio tests were used to assess linear trends across categories using values for quintile categories as the quantitative score of exposure. We also tested for effect modification by European region (North (Denmark, Sweden) vs Central (France, United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Germany) vs South (Italy, Spain, Greece)), time from blood donation to cancer diagnosis (≤3.6 (median follow-up time) yrs vs. >3.6 yrs), age (≤60 yrs vs. >60 yrs), sex, alcohol intake (0-30 grams/day vs. ≥30 grams/day), and plasma folate concentrations (≤11.3 nmol/L vs. >11.3 nmol/L; based on median concentrations in this cohort). Effect modification was tested by adding the product term of the B-vitamins (as categorical variables) and potential effect modifiers in the model. To investigate whether potential effect modification by alcohol intake was different for males and females, analyses were done by adding the product term of the B-vitamins, alcohol intake and sex in the model (while retaining lower order terms).

Associations between the polymorphisms and CRC risk were studied with conditional logistic regression. The risk estimates were calculated with the wild types - the most common genotypes in the natural population - as the reference categories. A trend test with equally spaced integer weights (0,1,2) for the genotypes was used to summarize the effect of each polymorphism. Effect modification of the SNP-CRC risk associations by B-vitamin concentrations and alcohol consumption were studied with conditional logistic regression, but by stratifying on country instead of the matched sets and with age and sex as covariates.

All statistical tests were performed with SAS statistical software, version 9.1. Statistical tests were 2-tailed and P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Characteristics of cases and controls

The distribution of sex, and mean age at recruitment was comparable among the 1365 cases and 2319 controls (Table 1). The median (range) follow up time between blood donation and the diagnosis of CRC was 3.6 (0.0–10.3) years. Apart from the concentration of the B6 vitamer PLP, which was higher in cases compared to their matched controls (P=0.02), the sum variables of vitamins B2 and B6, vitamin B12 and MMA concentrations were similar between cases and controls. The distribution of vitamin B2 and B6 among controls was skewed, with a longer tail at higher concentrations. Concentrations of the vitamin B6 species correlated strongly with each other after adjustment for age, sex and study center (Spearman correlation coefficients ranged from 0.64 to 0.74, all correlations P<0.01; data not shown). In addition, riboflavin correlated with FMN (0.34, P<0.01), and the correlation between vitamin B12 and MMA was −0.24 (P<0.01).

Table 1.

Characteristics of incident CRC cases and their matched controls

| Cases | Controls | Pdifference | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Number of individuals | 1365 | 2319 | |

| Sex, female, n (%) | 697 (51) | 1213 (52) | 0.54 |

| Mean age (y) (min-max) | |||

| At recruitment | 58.9 (30.1 - 76.9) | 58.7 (30.0 – 76.6) | 0.40 |

| At blood donation | 59.1 (36.8 - 77.0) | 58.9 (36.6 – 76.6) | 0.44 |

| At diagnosis | 62.8 (37.7 - 81.2) | n.a. | |

| Lag time | 3.6 (0.01 - 10.3) | n.a. | |

| Smoking status, n (%) | 0.02 | ||

| Never | 559 (41) | 1024 (44) | |

| Former | 447 (33) | 774 (33) | |

| Current | 344 (25) | 508 (22) | |

| Alcohol drinking, n (%) | < 0.01 | ||

| abstainers | 93 (7) | 166 (7) | |

| 1- 30 grams/ day | 983 (72) | 1784 (77) | |

| ≥ 30 grams/ day | 281 (21) | 372 (16) | |

| Median (5 -95 percentile) | |||

| Vitamin B2 sum (nmol/L) | 20.6 (9.4 - 65.7) | 20.6 (10.1 - 74.7) | 0.36 |

| Riboflavin (nmol/L) | 14.8 (6.1 - 60.6) | 14.8 (5.9 - 53.7) | 0.37 |

| FMN (nmol/L) | 5.4 (2.1 – 16.3) | 5.3 (1.9 - 15.3) | 0.20 |

| Vitamin B6 sum (nmol/L) | 63 (31 - 197) | 65 (32 – 222) | 0.20 |

| PLP (nmol/L) | 33.2 (14.2 – 111) | 32.1 (13.2 - 93.8) | <0.01 |

| PL (nmol/L) | 13.4 (6.7 - 44.0) | 13.1 (6.2 - 38.3) | 0.16 |

| PA (nmol/L) | 16.5 (7.8 - 72.5) | 17.3 (7.8 - 74.3) | 0.17 |

| Cobalamin (pmol/L) | 288 (162 - 498) | 288 (161 - 501) | 0.97 |

| MMA (μmol/L) | 0.17 (0.12 - 0.32) | 0.17 (0.12 - 0.30) | 0.32 |

Differences in plasma concentrations of the vitamins B2, B6, B12, and MMA were assessed by Wilcoxon signed rank test, while categorical variable differences were assessed by McNemar’s tests.

Compared to women, among men concentrations of the vitamin B2 sum and vitamin B12 were lower, whereas the vitamin B6 sum concentration was higher (Table 2). Participants younger than 60 years had lower vitamin B2 sum and MMA concentrations, and higher vitamin B12 concentrations, as compared to older individuals. Among current smokers, the vitamin B2 sum, vitamin B6 sum, and B12 concentrations were lower compared to former and never smokers. The sum variables of vitamin B2 and B6 were also lower among participants from Southern European countries compared to Central and Northern European countries. Individuals consuming ≥30 grams alcohol/day had lower concentrations of the vitamin B2 sum and vitamin B12 compared to those drinking less, except for vitamin B6. Finally, vitamin B12 concentrations were slightly higher in those with the variant TCN2 677GG genotype, whereas concentrations of other vitamins did not differ according to genotype (P for all differences>0.05; data not shown).

Table 2.

Concentrations (median (5 – 95 percentile)) of indices for vitamin B2, B6, and B12 by demographic and lifestyle characteristics in control cohort members (n=2319)

| Vitamin B2 indices | Vitamin B6 indices | Vitamin B12 indices | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Vitamin B2 sum (nmol/L) |

Riboflavin (nmol/L) |

FMN (nmol/L) |

Vitamin B6 sum (nmol/L) |

PLP (nmol/L) |

PL (nmol/L) |

PA (nmol/L) |

Cobalamin (pmol/L) |

MMA (μmol/L) |

||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Sex | Male | 1105 | 19.2 (9.5; 71.3) |

13.4 (5.6 - 58.9) |

5.3 (2.2 - 17.9) |

69.5 (33.5; 190.5) |

35.6 (15.1 - 97.4) |

13.8 (6.8 - 36.1) |

18.4 (8.5 - 56.5) |

274 (154 – 467) |

0.17 (0.12 - 0.32) |

| Female | 1213 | 21.8 (10.9; 77.0) |

16.2 (6.9 - 64.5) |

5.4 (2.0 - 15.7) |

60.5 (31.1; 288.5) |

31.2 (13.4 - 130.0) |

13.1 (6.6 - 58.1) |

15.2 (7.3 – 106) |

303 (170 – 517) |

0.17 (0.11 - 0.31) |

|

| Pdifference† | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.60 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.10 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.49 | ||

| Age | < 60 | 1274 | 20.0 (9.8; 73.3) |

13.8 (5.9 - 58.9) |

5.7 (2.2 - 16.4) |

62.9 (32.1; 217.8) |

33.9 (14.7 - 115.0) |

12.8 (6.5 - 41.9) |

15.6 (7.5 - 67.0) |

294 (167 – 488) |

0.16 (0.11 - 0.27) |

| ≥ 60 | 1044 | 21.4 (10.4; 74.7) |

15.9 (6.8 - 64.2) |

4.9 (2.0 - 15.8) |

66.2 (32.1; 228.2) |

32.8 (13.8 - 105.0) |

13.9 (6.9 - 45.9) |

17.7 (8.3 - 81.8) |

279 (153 – 506) |

0.18 (0.12 - 0.35) |

|

| Pdifference† | <0.005 | <.001 | <0.001 | 0.21 | 0.02 | <0.005 | <0.001 | <0.005 | <0.001 | ||

| Region* | North | 731 | 23.4 (12.3; 83.1) |

16.6 (6.8 - 64.2) |

6.5 (3.1 - 16.3) |

75.0 (34.0/ 328.6) |

36.9 (14.3 - 141.5) |

16.2 (6.5 - 76.0) |

21.1 (8.9 - 125) |

290 (166 - 478) |

0.17 (0.12 - 0.31) |

| Central | 999 | 21.5 (10.8; 80.9) |

16.0 (7.4 - 66.2) |

4.8 (1.9 - 16.5) |

65.4 (32.4; 211.3) |

33.0 (14.8 - 110.0) |

13.6 (7.3 - 37.1) |

16.3 (8.1 - 64.8) |

276 (161 – 481) |

0.18 (0.12 - 0.32) |

|

| South | 588 | 16.3 (8.1; 64.0) |

11.2 (4.8 - 51.5) |

4.9 (2.0 - 14.9) |

55.2 (28.6; 115.4) |

29.9 (13.3 - 73.2) |

11.0 (6.2 - 22.9) |

13.5 (6.5 - 29.6) |

304 (160 – 550) |

0.16 (0.11 - 0.31) |

|

| Pdifference‡ | <0.001 | <0.001 | <.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Smoking | Never | 1024 | 21.8 (11.2; 83.4) |

16.3 (7.0 - 68.7) |

5.5 (2.1 - 16.5) |

65.4 (33.3; 225.9) |

34.2 (15.5 - 109.0) |

13.7 (7.2 - 47.0) |

16.5 (8.1 - 75.9) |

296 (166 – 503) |

0.17 (0.12 - 0.30) |

| Former | 774 | 21.0 (9.6; 87.7) |

15.0 (6.3 - 71.8) |

5.3 (2.1 - 16.8) |

69.1 (34.0; 216.1) |

35.1 (15.5 - 120.0) |

14.2 (7.1 - 40.1) |

18.2 (8.5 - 71.0) |

283 (161 – 498) |

0.17 (0.12 - 0.32) |

|

| Current | 507 | 18.4 (9.5; 57.8) |

12.3 (5.1 - 47.0) |

5.4 (2.1 - 14.2) |

57 (26.5; 220.6) |

28.9 (11.8 - 105.0) |

11.9 (5.4 - 41.6) |

14.7 (6.6 - 64.9) |

277 (147 – 482) |

0.16 (0.11 - 0.33) |

|

| Ptrend§ | <0.005 | <0.005 | 0.22 | 0.91 | 0.05 | 0.76 | 0.78 | <0.005 | 0.91 | ||

| Alcohol | abstainer | 166 | 19.3 (8.9; 87.6) |

14.3 (5.7; 65.3) |

5.0 (2.2; 15.0) |

59.4 (25.7; 228.2) |

29.5 (12.2; 120.0) |

13.2 (5.2; 54.8) |

16.7 (6.8; 83.5) |

321 (183; 527) |

0.16 (0.11; 0.32) |

| (grams/day) | 1- 30 | 1784 | 21.0 (10.4; 73.3) |

15.3 (6.5; 62.6) |

5.3 (2.0; 15.8) |

63.4 (32.0; 227.9) |

32.2 (14.3; 109.0) |

13.2 (6.6; 44.7) |

16.3 (7.8; 74.3) |

287 (161; 496)0 |

0.17 (0.12; 0.32) |

| ≥ 30 | 372 | 19.4 (9.4; 76.2) |

12.7 (5.4; 53.7) |

6.0 (2.3; 21.4) |

75.5 (35.2; 207.7) |

41.7 (16.4; 116.0) |

14.8 (7.7; 38.4) |

19.2 (8.1; 57.3) |

280 (162; 481) |

0.16 (0.11; 0.28) |

|

| Pdifference† | 0.03 | <0.001 | <0.005 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.005 | <0.005 | ||

North: Sweden and Denmark; Central:United Kingdom

Pdifference (two-sided) calculated by Mann Whitney U test; abstainers were excluded from statistical analyses on alcohol consumption

Pdifference (two-sided) calculated by Kruskall Wallis test

Ptrend (two-sided) calculated by regression models

Associations between B-vitamins and CRC

Matched analyses revealed that vitamins B2 and B6 were inversely associated with CRC, with RRs per quintile ((95% CI), Ptrend) of 0.94 ((0.89-0.99), 0.02) for the sum of vitamin B2, and 0.94 ((0.89-0.99), 0.01) for the sum of vitamin B6 (Table 3). These associations were similar after further adjustment. Regarding the individual vitamers, risk reductions were strongest for FMN (5th vs. 1st quintile 35%, Ptrend<0.01), and for PLP (41%, Ptrend<0.01). When stratifying by anatomical site, these associations were observed for colon cancer risk, but not for rectal cancer risk with an exception for PLP. Vitamin B12 was not associated with CRC risk (Table 3), nor was plasma folate, as presented elsewhere (37). All the models as presented in Table 3 were also additionally adjusted for mutual B-vitamins and folate. However, these analyses did not materially change associations (data not shown).

Table 3.

Relative risks (95% CI)* for colorectal, colon, and rectal cancer by quintiles† of indices for vitamins B2, B6, and B12 status

| Matched analyses | Matched + covariate adjusted analyses | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | N cases/ controls |

RR/ quintile | Ptrend‡ | N cases/ controls |

RR/ quintile | Ptrend§ | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 |

|

|

|

||||||||||

| CRC | |||||||||||

| Vitamin B2 sum | 1336/ 2254 | 0.94 (0.89; 0.99) |

0.02 | 1296/ 2175 | 0.94 (0.88; 0.99) |

0.02 | 1 | 0.73 (0.58; 0.92) |

0.83 (0.65; 1.05) |

0.73 (0.57; 0.93) |

0.71 (0.56; 0.91) |

| Riboflavin | 1358/ 2315 | 0.97 (0.92; 1.02) |

0.21 | 1318/ 2236 | 0.97 (0.92; 1.02) |

0.27 | 1 | 0.88 (0.70; 1.10) |

0.84 (0.66; 1.07) |

0.84 (0.66; 1.07) |

0.87 (0.68; 1.11) |

| FMN | 1337/ 2254 | 0.89 (0.85; 0.95) |

<0.001 | 1297/ 2175 | 0.89 (0.84; 0.94) |

<0.001 | 1 | 0.77 (0.61; 0.97) |

0.81 (0.64; 1.02) |

0.54 (0.42; 0.69) |

0.65 (0.50; 0.83) |

| Vitamin B6 sum | 1338/ 2276 | 0.94 (0.89; 0.99) |

0.01 | 1298/ 2197 | 0.93 (0.88; 0.98) |

0.02 | 1 | 0.91 (0.72; 1.13) |

0.83 (0.66; 1.05) |

0.92 (0.73; 1.17) |

0.68 (0.53; 0.87) |

| PLP | 1359/ 2316 | 0.90 (0.85; 0.95) |

<0.001 | 1319/ 2237 | 0.89 (0.84; 0.94) |

<0.001 | 1 | 0.80 (0.64; 1.00) |

0.73 (0.58; 0.91) |

0.73 (0.57; 0.92) |

0.59 (0.47; 0.76) |

| PL | 1355/ 2302 | 0.95 (0.90; 1.00) |

0.06 | 1315/ 2223 | 0.90 (0.85; 0.95) |

0.03 | 1 | 0.79 (0.63; 0.99) |

0.73 (0.57; 0.93) |

0.84 (0.66; 1.07) |

0.70 (0.54; 0.90) |

| PA | 1346/ 2288 | 1.00 (0.95; 1.06) |

0.90 | 1306/ 2209 | 0.94 (0.89; 0.99) |

0.83 | 1 | 1.04 (0.82; 1.31) |

1.24 (0.98; 1.56) |

1.07 (0.84; 1.37) |

1.01 (0.78; 1.30) |

| Cobalamin | 1362/ 2303 | 1.02 (0.96; 1.07) |

0.58 | 1322/ 2225 | 1.03 (0.97; 1.08) |

0.19 | 1 | 0.86 (0.69; 1.08) |

1.02 (0.81; 1.28) |

1.08 (0.85; 1.35) |

1.02 (0.80; 1.29) |

| MMA | 1365/ 2313 | 0.99 (0.94; 1.04) |

0.72 | 1325/ 2234 | 1.02 (0.96; 1.08) |

0.97 | 1 | 1.09 (0.87; 1.36) |

1.16 (0.92; 1.46) |

1.18 (0.94; 1.49) |

0.94 (0.74; 1.21) |

| COLON | |||||||||||

| Vitamin B2 sum | 630/ 1436 | 0.91 (0.85; 0.97) |

<0.005 | 805/ 1392 | 0.91 (0.85; 0.97) |

0.01 | 1 | 0.74 (0.56; 1.00) |

0.72 (0.54; 0.97) |

0.66 (0.49; 0.89) |

0.66 (0.48; 0.90) |

| Riboflavin | 842/ 1467 | 0.95 (0.89; 1.02) |

0.15 | 817/ 1423 | 0.96 (0.89; 1.02) |

0.19 | 1 | 0.88 (0.66; 1.16) |

0.81 (0.60; 1.09) |

0.74 (0.55; 1.00) |

0.86 (0.63; 1.15) |

| FMN | 831/ 1436 | 0.86 (0.80; 0.92) |

<0.001 | 806/ 1392 | 0.87 (0.81; 0.93) |

<0.001 | 1 | 0.76 (0.58; 1.01) |

0.76 (0.57; 1.01) |

0.53 (0.39; 0.73) |

0.59 (0.43; 0.81) |

| Vitamin B6 sum | 829/ 1446 | 0.93 (0.87; 1.00) |

0.05 | 804/ 1402 | 0.93 (0.86; 1.00) |

0.01 | 1 | 0.93 (0.70; 1.23) |

0.75 (0.56; 1.01) |

0.89 (0.67; 1.20) |

0.69 (0.50; 0.96) |

| PLP | 843/ 1468 | 0.90 (0.85; 0.97) |

<0.005 | 818/ 1424 | 0.90 (0.84; 0.97) |

<0.005 | 1 | 0.79 (0.60; 1.04) |

0.62 (0.47; 0.83) |

0.74 (0.55; 0.99) |

0.63 (0.46; 0.86) |

| PL | 839/ 1460 | 0.95 (0.88; 1.02) |

0.13 | 814/ 1416 | 0.94 (0.87; 1.01) |

0.08 | 1 | 0.73 (0.54; 0.97) |

0.67 (0.49; 0.91) |

0.80 (0.59; 1.08) |

0.68 (0.49; 0.94) |

| PA | 834/ 1454 | 1.02 (0.95; 1.09) |

0.58 | 809/ 1410 | 1.02 (0.95; 1.09) |

0.63 | 1 | 1.11 (0.83; 1.50) |

1.28 (0.96; 1.72) |

1.13 (0.83; 1.54) |

1.07 (0.78; 1.48) |

| Cobalamin | 844/ 1461 | 1.00 (0.94; 1.07) |

0.97 | 819/ 1418 | 1.01 (0.94; 1.08) |

0.05 | 1 | 0.76 (0.57; 1.01) |

1.03 (0.77; 1.36) |

0.90 (0.67; 1.22) |

0.95 (0.70; 1.28) |

| MMA | 846/ 1467 | 0.97 (0.90; 1.04) |

0.34 | 821/ 1423 | 0.99 (0.92; 1.06) |

0.67 | 1 | 1.32 (0.99; 1.76) |

1.08 (0.81; 1.46) |

1.24 (0.93; 1.67) |

0.95 (0.69; 1.30) |

| RECTAL | |||||||||||

| Vitamin B2 sum | 506/ 818 | 1.00 (0.92; 1.09) |

0.96 | 491/ 783 | 0.99 (0.90; 1.09) |

0.81 | 1 | 0.73 (0.48; 1.09) |

1.14 (0.75; 1.73) |

0.94 (0.61; 1.43) |

0.84 (0.55; 1.28) |

| Riboflavin | 516/ 848 | 1.00 (0.91; 1.09) |

0.95 | 501/ 813 | 1.00 (0.91; 1.10) |

0.93 | 1 | 0.88 (0.59; 1.32) |

0.95 (0.63; 1.45) |

1.06 (0.69; 1.62) |

0.92 (0.60; 1.40) |

| FMN | 506/ 818 | 0.95 (0.87; 1.04) |

0.27 | 491/ 783 | 0.91 (0.83; 1.01) |

0.06 | 1 | 0.80 (0.53; 1.20) |

0.91 (0.60; 1.37) |

0.55 (0.36; 0.85) |

0.74 (0.48; 1.15) |

| Vitamin B6 sum | 509/ 830 | 0.95 (0.87; 1.03) |

0.19 | 494/ 795 | 0.94 (0.86; 1.03) |

0.20 | 1 | 0.85 (0.57; 1.25) |

1.06 (0.71; 1.57) |

1.01 (0.67; 1.51) |

0.69 (0.46; 1.04) |

| PLP | 516/ 848 | 0.90 (0.83; 0.98) |

0.01 | 501/ 813 | 0.89 (0.81; 0.97) |

0.01 | 1 | 0.84 (0.57; 1.23) |

1.01 (0.68; 1.49) |

0.74 (0.49; 1.11) |

0.58 (0.39; 0.87) |

| PL | 516/ 842 | 0.96 (0.88; 1.04) |

0.31 | 501/ 807 | 0.95 (0.87; 1.04) |

0.28 | 1 | 0.93 (0.63; 1.37) |

0.86 (0.58; 1.27) |

0.96 (0.64; 1.45) |

0.77 (0.51; 1.17) |

| PA | 512/ 834 | 0.98 (0.90; 1.08) |

0.72 | 497/ 799 | 1.00 (0.91; 1.10) |

0.98 | 1 | 0.93 (0.63; 1.38) |

1.20 (0.82; 1.76) |

1.02 (0.68; 1.53) |

0.95 (0.63; 1.45) |

| Cobalamin | 518/ 842 | 1.04 (0.96; 1.13) |

0.31 | 503/ 807 | 1.06 (0.97; 1.15) |

0.23 | 1 | 1.15 (0.78; 1.70) |

1.00 (0.68; 1.46) |

1.42 (0.97; 2.07) |

1.17 (0.80; 1.73) |

| MMA | 519/ 846 | 1.03 (0.95; 1.12) |

0.50 | 504/ 811 | 1.03 (0.94; 1.12) |

0.54 | 1 | 0.82 (0.56; 1.20) |

1.33 (0.91; 1.93) |

1.15 (0.79; 1.69) |

0.96 (0.64; 1.43) |

NOTE: Counts do not necessarily add to the total sum due to missing data.

lower quintile is reference category. All analyses are matched for age, sex, study center and date of blood collection. The matched + covariate adjusted analyses are further adjusted for smoking status, education level, physical activity, fiber intake, intake of red and processed meat, alcohol consumption, and BMI.

The cut off values for the quintiles of the vitamin B2 sum were 14.2, 18.1, 23.5, and 33.4 μmol/L; for riboflavin they were 9.4, 12.8, 17.2, and 25.4 μmol/L; for FMN they were 3.3, 4.6, 6.3, and 8.8 μmol/L; for the vitamin B6 sum they were 45.4, 57.7, 72.6, and 105.3 μmol/L; for PLP they were 21.7, 29.1, 38.4, and 56.6 μmol/L; for PL they were 9.4, 11.8, 15.0, and 20.6 μmol/L; for PA they were 11.1, 14.6, 19.2, and 29.0 μmol/L; for vitamin B12 they were 220, 266, 312, and 380 pmol/L; and for MMA they were 0.14, 0.16, 0.18, and 0.22 μmol/L.

Ptrend (two-sided) in risk calculated with conditional logistic regression models without any covariates in the model using values for quintile categories as the quantitative score of exposure

Ptrend (two-sided) in risk calculated with conditional logistic regression models with the covariates in the model using values for quintile categories as the quantitative score of exposure

We also assessed potential effect modification of the vitamin – CRC associations by sex, age, European region, time between blood donation and cancer diagnoses, and plasma folate concentrations. The association between vitamin B2 and CRC was modified by folate status (Pinteraction=0.03), whereby an inverse association of the sum of vitamin B2 and CRC was observed among individuals with folate concentrations >11.3 nmol/L (51% risk reduction for the 5th vs. 1st quintile, Ptrend<0.01), and a 7% risk increase among subjects with folate concentrations <11.3 nmol/L (Ptrend=0.71). Although none of the other interaction terms were statistically significant, we also observed significant trends for the associations between vitamin B2 sum and vitamin B6 sum with CRC risk among females, individuals younger than 60 years, and those living in Central European countries. Furthermore, the association of vitamin B6 with CRC risk was stronger in individuals diagnosed within the first 3.6 years after enrollment compared to associations in individuals diagnosed later. Relative risks of 5th vs. 1st quintile (95%CI), Ptrend) observed within the first 3.6 years were 0.61 ((0.43 - 0.86), <0.01) for the sum of vitamin B6, 0.55 ((0.39 - 0.77), <0.01) for PLP, and 0.59 ((0.41 - 0.83), <0.01) for PL. Relative risks observed after the first 3.6 years were 0.80 ((0.56 - 1.14), 0.43) for the sum of vitamin B6, 0.67 ((0.48 - 0.94), 0.05) for PLP, and 0.88 ((0.63 - 1.25), 0.86) for PL. However, lag time did not significantly modify the overall association between the sum of vitamin B6, PLP, and PL with CRC risk, as indicated by Pinteraction of 0.48, 0.57, and 0.29, respectively.

In addition, we explored the associations between the vitamins and CRC risk by subgroups of alcohol intake, and observed stronger inverse associations of the vitamin B2 sum and the vitamin B6 sum with CRC risk in individuals drinking ≥30 grams alcohol/day (Table 4). Further stratification of these alcohol analyses by sex revealed even stronger inverse associations for the vitamin B6 sum in males consuming ≥30 grams alcohol/day compared to males who drink less alcohol (Ptrend<0.01; Pinteraction=0.01). Associations between individual vitamin B2 and B6 species with CRC risk in subgroups of alcohol intake did not differ materially from those associations observed for sum scores. Furthermore, stratified analyses using a cut off point of 15 g alcohol/day did not materially alter associations between any of the B-vitamins and CRC risk (data not shown).

Table 4.

Adjusted relative risks (95% CI)* for colorectal cancer by quintiles† of indices for vitamins B2, B6, and B12 status by alcohol consumption and sex

| Alcohol | N cases/ controls |

Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Ptrend‡ | Pinteraction§ | Pinteraction|| | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Vitamin B2 sum | ||||||||||

| Overall | Abstainer | 83/ 144 | 1 | 0.88 (0.30; 2.54) |

1.51 (0.48; 4.72) |

1.01 (0.31; 3.23) |

1.06 (0.31; 3.72) |

0.82 | ||

| 1-30 g/d | 939/ 1671 | 1 | 0.83 (0.63; 1.09) |

0.92 (0.70; 1.20) |

0.85 (0.65; 1.12) |

0.83 (0.63; 1.09) |

0.27 | |||

| ≥ 30 g/d | 274/ 360 | 1 | 0.55 (0.33; 0.92) |

0.65 (0.39; 1.10) |

0.60 (0.34; 1.04) |

0.56 (0.32; 0.98) |

0.07 | 0.21 | ||

| Males | 1-30 g/d | 386/ 700 | 1 | 0.80 (0.53; 1.22) |

1.23 (0.82; 1.85) |

1.16 (0.76; 1.76) |

0.87 (0.56; 1.35) |

0.82 | ||

| ≥ 30 g/d | 220/ 285 | 1 | 0.50 (0.28; 0.89) |

0.66 (0.37; 1.19) |

0.76 (0.41; 1.40) |

0.50 (0.26; 0.96) |

0.15 | 0.14 | ||

| Females | 1-30 g/d | 553/ 971 | 1 | 0.84 (0.58; 1.20) |

0.75 (0.52; 1.08) |

0.69 (0.48; 0.99) |

0.80 (0.57; 1.14) |

0.17 | 0.27 | |

| ≥ 30 g/d | 54/ 75 | 1 | 0.58 (0.14; 2.40) |

0.53 (0.14; 1.94) |

0.20 (0.04; 0.99) |

0.52 (0.15; 1.80) |

0.22 | 0.55 | 0.91 | |

| Vitamin B6 sum | ||||||||||

| Overall | Abstainer | 86/ 149 | 1 | 0.53 (0.20; 1.41) |

0.73 (0.27; 1.96) |

1.04 (0.39; 2.80) |

0.39 (0.11; 1.39) |

0.54 | ||

| 1-30 g/d | 940/ 1691 | 1 | 0.92 (0.71; 1.18) |

0.78 (0.60; 1.02) |

0.91 (0.70; 1.19) |

0.76 (0.58; 1.01) |

0.09 | |||

| ≥ 30 g/d | 272/ 357 | 1 | 0.94 (0.49; 1.80) |

0.91 (0.47; 1.76) |

0.70 (0.37; 1.35) |

0.55 (0.28; 1.07) |

0.03 | 0.12 | ||

| Males | 1-30 g/d | 392/ 718 | 1 | 1.18 (0.77; 1.80) |

0.80 (0.52; 1.23) |

1.17 (0.77; 1.77) |

0.80 (0.51; 1.26) |

0.44 | ||

| ≥ 30 g/d | 218/ 282 | 1 | 0.56 (0.25; 1.25) |

0.50 (0.22; 1.13) |

0.41 (0.19; 0.91) |

0.34 (0.15; 0.76) |

0.01 | 0.01 | ||

| Females | 1-30 g/d | 548/ 973 | 1 | 0.79 (0.58; 1.08) |

0.80 (0.57; 1.12) |

0.77 (0.54; 1.10) |

0.76 (0.53; 1.09) |

0.14 | 0.50 | |

| ≥ 30 g/d | 54/ 75 | 1 | 2.21 (0.52; 9.36) |

1.79 (0.40; 8.07) |

3.19 (0.67; 15.20) |

0.92 (0.19; 4.49) |

0.86 | 0.34 | 0.03 | |

| Cobalamin | ||||||||||

| Overall | Abstainer | 88/ 154 | 1 | 0.36 (0.12; 1.11) |

0.77 (0.27; 2.26) |

0.75 (0.28; 2.01) |

0.56 (0.21; 1.53) |

0.66 | ||

| 1-30 g/d | 959/ 1708 | 1 | 0.94 (0.73; 1.22) |

1.10 (0.86; 1.42) |

1.06 (0.82; 1.38) |

1.05 (0.80; 1.37) |

0.49 | |||

| ≥ 30 g/d | 275/ 363 | 1 | 0.76 (0.46; 1.26) |

0.68 (0.41; 1.15) |

1.00 (0.60; 1.68) |

0.93 (0.54; 1.60) |

0.91 | 0.76 | ||

| Males | 1-30 g/d | 401/ 722 | 1 | 0.97 (0.67; 1.41) |

1.27 (0.88; 1.83) |

1.11 (0.75; 1.66) |

1.07 (0.69; 1.65) |

0.48 | ||

| ≥ 30 g/d | 221/ 289 | 1 | 0.93 (0.53; 1.64) |

0.73 (0.41; 1.31) |

1.07 (0.59; 1.96) |

0.99 (0.53; 1.84) |

0.93 | 0.66 | ||

| Females | 1-30 g/d | 558/ 986 | 1 | 0.89 (0.62; 1.29) |

0.96 (0.68; 1.37) |

1.03 (0.73; 1.45) |

1.00 (0.71; 1.41) |

0.72 | 0.76 | |

| ≥ 30 g/d | 54/ 74 | 1 | 0.45 (0.11; 1.76) |

0.58 (0.14; 2.31) |

0.73 (0.22; 2.45) |

0.71 (0.19; 2.59) |

0.80 | 0.90 | 0.78 | |

| MMA | ||||||||||

| Overall | Abstainer | 88/ 155 | 1 | 1.16 (0.45; 2.96) |

1.97 (0.68; 5.73) |

0.92 (0.33; 2.59) |

1.20 (0.43; 3.36) |

0.93 | ||

| 1-30 g/d | 961/ 1714 | 1 | 1.07 (0.82; 1.40) |

1.10 (0.85; 1.43) |

1.17 (0.90; 1.53) |

0.91 (0.69; 1.21) |

0.80 | |||

| ≥ 30 g/d | 276/ 365 | 1 | 1.45 (0.88; 2.39) |

1.28 (0.75; 2.17) |

1.28 (0.76; 2.17) |

1.28 (0.73; 2.27) |

0.53 | 0.63 | ||

| Males | 1-30 g/d | 400/ 723 | 1 | 1.19 (0.79; 1.81) |

1.33 (0.88; 2.03) |

1.22 (0.80; 1.85) |

1.01 (0.66; 1.54) |

0.98 | ||

| ≥ 30 g/d | 222/ 290 | 1 | 1.62 (0.92; 2.84) |

1.56 (0.86; 2.84) |

1.49 (0.83; 2.69) |

1.51 (0.81; 2.83) |

0.24 | 0.40 | ||

| Females | 1-30 g/d | 561/ 991 | 1 | 1.01 (0.71; 1.43) |

0.98 (0.70; 1.37) |

1.19 (0.84; 1.68) |

0.86 (0.59; 1.24) |

0.80 | 0.98 | |

| ≥ 30 g/d | 54/ 75 | 1 | 1.30 (0.37; 4.61) |

0.58 (0.13; 2.52) |

0.87 (0.23; 3.28) |

0.72 (0.14; 3.67) |

0.52 | 0.32 | 0.31 | |

NOTE: Counts do not necessarily add to the total sum due to missing data.

lower quintile is reference category. All analyses are matched for age, sex, study center and date of blood collection and further adjusted for smoking status, education level, physical activity, fiber intake, intake of red and processed meat, alcohol consumption, and BMI.

The cut off values for the quintiles of vitamin B2 sum were 14.2, 18.1, 23.5, and 33.4 μmol/L; for the vitamin B6 sum they were 45.4, 57.7, 72.6, and 105.3 μmol/L; for vitamin B12 they were 220, 266, 312, and 380 pmol/L; and for MMA they were 0.14, 0.16, 0.18, and 0.22 μmol/L.

Ptrend (two-sided) in risk calculated with conditional logistic regression models with the covariates in the model using values for quintile categories as the quantitative score of exposure

Pinteraction (two-sided) of the vitamin – CRC association by alcohol consumption (abstainers excluded) for the overall model, and separately for males and females.

Pinteraction (two-sided) of the vitamin – CRC association by sex, separately for individuals with low alcohol consumption (abstainers excluded) and high alcohol consumption.

The polymorphisms and their associations with CRC risk

All the SNPs were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (χ2 test P-values >0.05 for all SNPs). Table 5 shows that the genotype distributions of the CBS 699C→T, CBS 844ins68, TCN2 67A→G, and TCN2 776C→G polymorphisms did not differ among colorectal, colon, and rectal cases and their matched controls, nor were these polymorphisms associated with cancer risk. Stratification by European region yielded similar associations between the studied genotypes and CRC risk (data not shown).

Table 5.

Distribution of genotypes by cancer site, and their associations with CRC risk

| CRC-ALL | COLON | RECTAL | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | N cases/ controls |

OR (95% CI) | N cases/ controls |

OR (95% CI) | N cases/ controls |

OR (95% CI) | |

|

|

|

|

|||||

| CBS 699 | CC | 583/1056 | 1 | 356/ 702 | 1 | 226/ 361 | 1 |

| CT | 603/1040 | 1.04 (0.90; 1.21) | 374/ 656 | 1.12 (0.94; 1.35) | 230/ 389 | 0.93 (0.74; 1.18) | |

| TT | 141/ 253 | 1.00 (0.79; 1.26) | 83/ 148 | 1.11 (0.82; 1.50) | 58/ 103 | 0.87 (0.60; 1.25) | |

| Ptrend | 0.78 | 0.25 | 0.39 | ||||

| CBS ins | 0 ins | 1233/2150 | 1 | 761/ 1367 | 1 | 472/ 783 | 1 |

| 1 ins | 212/ 358 | 1.02 (0.85; 1.23) | 137/ 231 | 1.04 (0.83; 1.31) | 75/ 127 | 1.00 (0.73; 1.36) | |

| 2 ins | 9/ 18 | 0.89 (0.40; 2.00) | 4/ 12 | 0.65 (0.21; 2.04) | 5/ 6 | 1.29 (0.39; 4.34) | |

| Ptrend | 0.89 | 0.96 | 0.87 | ||||

| TCN2 67 | AA | 1026/1789 | 1 | 622/ 1147 | 1 | 406/ 649 | 1 |

| AG | 263/ 490 | 0.95 (0.80; 1.12) | 162/ 312 | 0.98 (0.79; 1.21) | 100/ 181 | 0.87 (0.66; 1.15) | |

| GG | 19/18 | 0.87 (0.50; 1.53) | 13/ 22 | 1.03 (0.51; 2.08) | 5/ 16 | 0.54 (0.20; 1.51) | |

| Ptrend | 0.42 | 0.88 | 0.15 | ||||

|

TCN2 776 |

CC | 415/ 749 | 1 | 253/ 482 | 1 | 162/ 273 | 1 |

| CG | 648/1170 | 0.99 (0.85; 1.16) | 401/ 762 | 0.99 (0.81; 1.20) | 248/ 412 | 1.01 (0.78; 1.30) | |

| GG | 266/ 435 | 1.10 (0.90; 1.33) | 160/ 266 | 1.13 (0.88; 1.46) | 105/ 169 | 1.04 (0.76; 1.43) | |

| Ptrend | 0.45 | 0.42 | 0.81 | ||||

wildtype is reference category.

Most of the associations between the SNPs and CRC were not modified by quintiles of B-vitamin status (Pinteraction>0.19 for all relevant interactions; data not shown). A previous report (37), included MTHFR 677C→T, MTHFR 1298A→C, MTR 2756A→G, and MTRR 66A→G polymorphisms, which were not independently associated with CRC risk. However, among these SNPs, we observed effect modification of the association between MTRR 66A→G and CRC risk by vitamin B2 status as measured in the current study (Pinteraction=0.04). The variant MTRR 66GG genotype conferred a statistically significant lower CRC risk in individuals with concentrations <18.1 nmol/L of the sum of B2: RR=0.57 (CI: 0.35-0.93, Ptrend=0.02), whereas a statistically non-significant higher CRC risk was observed in individuals with concentrations >33.4 nmol/L (RR (95% CI, Ptrend) GG vs. AA=1.24 (0.75-2.04, 0.51). Finally, the SNP-CRC associations were neither modified by B-vitamin concentrations, nor by alcohol consumption (Pinteractions>0.05; data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this large European cohort, we investigated the associations of plasma vitamins B2, B6, B12, and genetic variants of the one-carbon metabolism with CRC risk. Overall, plasma vitamin B2 and B6 status were inversely associated with CRC. In addition, we observed that the inverse association between vitamin B6 and CRC was more pronounced among males who consumed more than 30 grams of alcohol/day. None of the SNPs were associated with CRC risk, and generally the vitamins did not modify these associations.

The present study is the largest prospective study on plasma B-vitamins and CRC risk published so far, allowing for well powered subgroup analyses. Extensive information on lifestyle factors enabled us to control for potential confounders and assessment of possible effect modifications. Another important strength of this study is the collection of blood samples prior to cancer diagnosis. Also, study centers collected and stored blood samples according to a standardized protocol (27), and all biochemical analyses were performed in one laboratory, thereby optimizing sample treatment and avoiding between-laboratory method variability. The overall observed associations between the vitamins and age, sex, and smoking status (23, 33, 38) are in line with previous findings, supporting the integrity of biochemical data. Furthermore, the range of plasma concentrations observed for vitamin B12 (10) and vitamin B6 (9) are comparable to those in other European studies, whereas vitamin B6 concentrations were slightly lower compared to those observed in American studies (39-41), which may be explained by widespread supplement use in the USA. Data on supplement use, and specifically use of B-vitamins, in the EPIC cohort are sparse. However, in a subsample of the EPIC population, single 24-hour recalls revealed a clear north-south gradient in supplement use, with higher consumption in Northern than in Southern European countries, and higher consumption for women than for men (42). Moreover, none of the European countries applied mandatory fortification of any of the B-vitamins. As national fortification policies vary considerably throughout the European Union, the European Commission aims to harmonise voluntary food fortification across European countries in the near future (43).

Two out of four studies on the associations between vitamin B6 and CRC (9, 39-41) reported median follow-up time of 6 years (9) and 10 years (41), compared to the present study with a median follow up time of 3.6 years. A potential drawback of cohort studies with relatively short follow up is reverse causality, i.e. the phenomenon that preclinical disease influences exposure status. This is more likely to affect individuals diagnosed early than those diagnosed later. In this respect, Lee et al (41) previously observed a stronger inverse association between vitamin B6 and CRC in an earlier compared to a later follow-up period. Although in our study, the associations between vitamin B6 sum and all its individual species and risk of CRC appeared more pronounced in those diagnosed within the first years of follow-up compared to those diagnosed later, it should be emphasized that there was no statistical evidence for effect modification by the duration of follow-up. Nevertheless, to present analyses according to different lengths of follow-up time should be recommended in future studies.

The most important dietary sources of vitamin B2 are milk and dairy products (44), whereas vitamin B6 may be obtained from various food groups, including fruit, vegetables and meat (45). After ingestion, free FMN and FAD are converted to riboflavin, whereas all vitamin B6 species are converted into PLP and PL. FMN acts as a cofactor and PA is the catabolite product of these reactions (36, 45). As the sum variables for vitamin B2 and vitamin B6 might account for any interconversion between the two B2 species (35, 46-48) and the three B6 species (36, 45, 49), they are used as a supplementary variable to determine vitamin B2 and vitamin B6 status, respectively.

Few epidemiological studies have investigated plasma concentrations of B-vitamins in relation to CRC risk (9, 10, 39, 41). The present study observed a risk reduction of 29% for individuals in the highest quintile of the sum of vitamin B2 concentration compared to those in the lowest quintile. Though riboflavin has been suggested as the best plasma marker of vitamin B2 status (50), no relation with CRC was found for riboflavin, whereas it was found for FMN. FMN serves as a cofactor in the synthesis of PLP (2, 51), which is the active form of vitamin B6. Interestingly, in line with previous studies on plasma PLP (39, 41), we observed an inverse association between the sum of vitamin B6 and CRC. We did not observe an association between plasma vitamin B12 and its marker MMA and CRC, whereas Dahlin et al (10) observed that plasma vitamin B12 was inversely associated with rectal cancer. In the Aspirin/Folate Polyp Prevention Study, which investigated the effects of folic acid supplementation on incidence of new colorectal adenomas in persons with a history of adenomas, high plasma concentrations of PLP and riboflavin at baseline seem to protect against colorectal adenomas (52). Methodological differences in cross-sectional, prospective, and intervention studies, as well as differences between data on intake (3-8, 11-13, 26) and plasma concentrations (9, 10, 14, 39, 41), may have resulted in inconsistencies between studies. However, taking all epidemiological studies into account, current evidence suggests a role for the vitamins B2 and B6 in colorectal carcinogenesis.

Notably, folate and vitamin B12 are carriers of one-carbon units, whereas vitamins B2 (53) and B6 (54) are involved in many pathways other than one-carbon metabolism. Vitamin B2 serves as co-factor in fat, amino acid, carbohydrate and vitamin metabolisms (53), whereas vitamin B6 has been shown to reduce oxidative stress, affects cell proliferation and angiogenesis (55). As CRC risk was not related to concentrations of folate (37) and vitamin B12 in this cohort, the inverse association between risk and vitamin B2 and B6 may reflect mechanisms not involving one-carbon metabolism. Both vitamin B2 and B6 are cofactors within the kynurenine metabolism which is related to inflammation (56). An inverse association of PLP with the inflammatory marker C-reative protein, which has been related to several cancer types, has also been reported (57).

Alcohol consumption may reduce bioavailability of folate (58) and vitamin B6 (59). So far, only two studies investigated the interaction between vitamin B6 status, alcohol consumption and CRC (39, 60), and both studies suggest that a sufficient vitamin B6 status may prevent development of colorectal cancer particular in persons with high alcohol consumption, results which are in agreement with data for males of the present study.

Regarding the role of genetic variants in the one-carbon metabolism and CRC, we did not observe that the polymorphisms investigated were associated with CRC. Although some associations have been reported, previous studies did not consistently demonstrate associations of similar one-carbon SNPs and CRC (4, 18-21, 23). Furthermore, generally variable B-vitamin status did not modify the associations between SNPsand CRC risk. Despite the large study population, the sample size might still have been too small to detect associations with CRC risk, interactions between genes and European region, and interactions between genes and vitamins, and may also have resulted in chance findings. Nevertheless, we observed that the association between MTRR 66A→G and CRC was modified by vitamin B2 status. Furthermore, the polymorphisms presented in this study may not cover all genetic variability of the studied genes, however, they represent a collection of polymorphisms in genes encoding central enzymes of the one-carbon metabolism. All these variants have been demonstrated to influence one-carbon metabolism (61) and some have been related to cancer (18, 19, 23). Future studies could adopt a more pathway-oriented approach to the data analysis in a mathematical model, integrating all the B-vitamins and polymorphisms involved in the one-carbon metabolism (62).

In summary, this large prospective European multicenter study revealed that plasma concentrations of vitamins B2 and B6 were inversely associated with CRC risk. However, unlike preceding studies, none of the studied polymorphisms related to one-carbon metabolism were associated with CRC in this large European cohort.

Acknowledgments

Financial support

European Commission: Public Health and Consumer Protection Directorate 1993-2004; Research Directorate-General 2005; Ligue contre le Cancer (France); Société 3M (France); Mutuelle Générale de l’Education Nationale; Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM); German Cancer Aid; German Cancer Research Center; German Federal Ministry of Education and Research; Danish Cancer Society; Health Research Fund (FIS) of the Spanish Ministry of Health (RCESP-C03/09; RTICCC (C03/10); the participating regional governments and institutions of Spain; Cancer Research UK; Medical Research Council, UK; Stroke Association, UK; British Heart Foundation; Department of Health, UK; Food Standards Agency, UK; Wellcome Trust, UK; Greek Ministry of Health and Social Solidarity; Hellenic Health Foundation and Stavros Niarchos Foundation; Italian Association for Research on Cancer (AIRC); Compagnia San Paolo, Italy; Dutch Ministry of Public Health, Welfare and Sports; Dutch Ministry of Health; Dutch Prevention Funds; LK Research Funds; Dutch ZON (Zorg Onderzoek Nederland); World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF); Swedish Cancer Society; Swedish Scientific Council; Regional Government of Skane, Sweden; Norwegian Cancer Society; Foundation to promote research into functional vitamin B12-deficiency, Norway. We would like to thank B. Hemon and C. Casagrande (IARC-WHO) for their assistance in database preparation, and Tove Følid, Halvard Bergesen, and Gry Kvalheim (Section for Pharmacology, University of Bergen) for their laboratory assistance in analyses of B-vitamins.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Kim YI. Folate and colorectal cancer: an evidence-based critical review. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2007;51:267–92. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200600191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCormick DB. Two interconnected B vitamins: riboflavin and pyridoxine. Physiol Rev. 1989;69:1170–98. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1989.69.4.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.La Vecchia C, Braga C, Negri E, et al. Intake of selected micronutrients and risk of colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 1997;73:525–30. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19971114)73:4<525::aid-ijc12>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Le Marchand L, Donlon T, Hankin JH, Kolonel LN, Wilkens LR, Seifried A. B-vitamin intake, metabolic genes, and colorectal cancer risk (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2002;13:239–48. doi: 10.1023/a:1015057614870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Otani T, Iwasaki M, Hanaoka T, et al. Folate, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, and vitamin B2 intake, genetic polymorphisms of related enzymes, and risk of colorectal cancer in a hospital-based case-control study in Japan. Nutr Cancer. 2005;53:42–50. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5301_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shin A, Li H, Shu XO, Yang G, Gao YT, Zheng W. Dietary intake of calcium, fiber and other micronutrients in relation to colorectal cancer risk: Results from the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2938–42. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murtaugh MA, Curtin K, Sweeney C, et al. Dietary intake of folate and co-factors in folate metabolism, MTHFR polymorphisms, and reduced rectal cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18:153–63. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0099-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharp L, Little J, Brockton NT, et al. Polymorphisms in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene, intakes of folate and related B vitamins and colorectal cancer: a case-control study in a population with relatively low folate intake. Br J Nutr. 2008;99:379–89. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507801073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinstein SJ, Albanes D, Selhub J, et al. One-carbon metabolism biomarkers and risk of colon and rectal cancers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:3233–40. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dahlin AM, Van Guelpen B, Hultdin J, Johansson I, Hallmans G, Palmqvist R. Plasma vitamin B12 concentrations and the risk of colorectal cancer: a nested case-referent study. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:2057–61. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harnack L, Jacobs DR, Jr., Nicodemus K, Lazovich D, Anderson K, Folsom AR. Relationship of folate, vitamin B-6, vitamin B-12, and methionine intake to incidence of colorectal cancers. Nutr Cancer. 2002;43:152–8. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC432_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishihara J, Otani T, Inoue M, Iwasaki M, Sasazuki S, Tsugane S. Low intake of vitamin B-6 is associated with increased risk of colorectal cancer in Japanese men. J Nutr. 2007;137:1808–14. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.7.1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kune G, Watson L. Colorectal cancer protective effects and the dietary micronutrients folate, methionine, vitamins B6, B12, C, E, selenium, and lycopene. Nutr Cancer. 2006;56:11–21. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5601_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma J, Stampfer MJ, Christensen B, et al. A polymorphism of the methionine synthase gene: association with plasma folate, vitamin B12, homocyst(e)ine, and colorectal cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8:825–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larsson SC, Orsini N, Wolk A. Vitamin B6 and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Jama. 2010;303:1077–83. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen J, Giovannucci E, Hankinson SE, et al. A prospective study of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase and methionine synthase gene polymorphisms, and risk of colorectal adenoma. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:2129–32. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.12.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ulvik A, Vollset SE, Hansen S, Gislefoss R, Jellum E, Ueland PM. Colorectal cancer and the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase 677C -> T and methionine synthase 2756A -> G polymorphisms: a study of 2,168 case-control pairs from the JANUS cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:2175–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hazra A, Wu K, Kraft P, Fuchs CS, Giovannucci EL, Hunter DJ. Twenty-four non-synonymous polymorphisms in the one-carbon metabolic pathway and risk of colorectal adenoma in the Nurses’ Health Study. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1510–9. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koushik A, Kraft P, Fuchs CS, et al. Nonsynonymous polymorphisms in genes in the one-carbon metabolism pathway and associations with colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:2408–17. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ott N, Geddert H, Sarbia M. Polymorphisms in methionine synthase (A2756G) and cystathionine beta-synthase (844ins68) and susceptibility to carcinomas of the upper gastrointestinal tract. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134:405–10. doi: 10.1007/s00432-007-0301-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pufulete M, Al-Ghnaniem R, Rennie JA, et al. Influence of folate status on genomic DNA methylation in colonic mucosa of subjects without colorectal adenoma or cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:838–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shannon B, Gnanasampanthan S, Beilby J, Iacopetta B. A polymorphism in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene predisposes to colorectal cancers with microsatellite instability. Gut. 2002;50:520–4. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.4.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharp L, Little J. Polymorphisms in genes involved in folate metabolism and colorectal neoplasia: a HuGE review. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:423–43. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hustad S, Midttun Ø , Schneede J, Vollset SE, Grotmol T, Ueland PM. The methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase 677C-->T polymorphism as a modulator of a B vitamin network with major effects on homocysteine metabolism. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:846–55. doi: 10.1086/513520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ulrich CM. Nutrigenetics in cancer research--folate metabolism and colorectal cancer. J Nutr. 2005;135:2698–702. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.11.2698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larsson SC, Giovannucci E, Wolk A. Vitamin B6 intake, alcohol consumption, and colorectal cancer: a longitudinal population-based cohort of women. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1830–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riboli E, Kaaks R. The EPIC Project: rationale and study design. European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26(Suppl 1):S6–14. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.suppl_1.s6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bergstralh EJ, Kosanke JL, Jacobsen SJ. Software for optimal matching in observational studies. Epidemiology. 1996;7:331–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenbaum P. Optimal matching for observational studies. J Am Stat Assoc. 1989;84:1024–32. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Midttun Ø , Hustad S, Solheim E, Schneede J, Ueland PM. Multianalyte quantification of vitamin B6 and B2 species in the nanomolar range in human plasma by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Chem. 2005;51:1206–16. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.051169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kelleher BP, Broin SD. Microbiological assay for vitamin B12 performed in 96-well microtitre plates. J Clin Pathol. 1991;44:592–5. doi: 10.1136/jcp.44.7.592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Windelberg A, Arseth O, Kvalheim G, Ueland PM. Automated assay for the determination of methylmalonic acid, total homocysteine, and related amino acids in human serum or plasma by means of methylchloroformate derivatization and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Clin Chem. 2005;51:2103–9. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.053835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyer K, Fredriksen A, Ueland PM. High-level multiplex genotyping of polymorphisms involved in folate or homocysteine metabolism by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. Clin Chem. 2004;50:391–402. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.026799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meyer K, Fredriksen A, Ueland PM. MALDI-TOF MS genotyping of polymorphisms related to 1-carbon metabolism using common and mass-modified terminators. Clin Chem. 2009;55:139–49. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.115378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foraker AB, Khantwal CM, Swaan PW. Current perspectives on the cellular uptake and trafficking of riboflavin. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2003;55:1467–83. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coburn SP. Modeling vitamin B6 metabolism. Adv Food Nutr Res. 1996;40:107–32. doi: 10.1016/s1043-4526(08)60023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eussen S, Vollset S, Igland J, et al. Plasma folate, related genetic variants and colorectal cancer risk in EPIC. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0841. Accepted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Bree A, Verschuren WM, Kromhout D, Kluijtmans LA, Blom HJ. Homocysteine determinants and the evidence to what extent homocysteine determines the risk of coronary heart disease. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:599–618. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wei EK, Giovannucci E, Selhub J, Fuchs CS, Hankinson SE, Ma J. Plasma vitamin B6 and the risk of colorectal cancer and adenoma in women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:684–92. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Le Marchand L, White KK, Nomura AM, et al. Plasma levels of B vitamins and colorectal cancer risk: the multiethnic cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2195–201. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee JE, Li H, Giovannucci E, et al. Prospective study of plasma vitamin B6 and risk of colorectal cancer in men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:1197–202. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skeie G, Braaten T, Hjartåker A, et al. Use of dietary supplements in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition calibration study. Eur J Clin Nutr. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2009.83. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.European Commission Health and Consumer Protection Directorate-General . Discussion paper on the setting of maximum and minimum amounts for vitamins and minerals in foodstuffs. European Communities; Brussels, Belgium: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Powers HJ. Riboflavin (vitamin B-2) and health. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:1352–60. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.6.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leklem J. Present knowledge in nutrition. ILSI Press; Washington, DC: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Merrill AH, Jr., McCormick DB. Affinity chromatographic purification and properties of flavokinase (ATP:riboflavin 5′-phosphotransferase) from rat liver. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:1335–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamada Y, Merrill AH, Jr., McCormick DB. Probable reaction mechanisms of flavokinase and FAD synthetase from rat liver. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1990;278:125–30. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(90)90240-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karthikeyan S, Zhou Q, Mseeh F, Grishin NV, Osterman AL, Zhang H. Crystal structure of human riboflavin kinase reveals a beta barrel fold and a novel active site arch. Structure. 2003;11:265–73. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Midttun Ø , Hustad S, Schneede J, Vollset SE, Ueland PM. Plasma vitamin B-6 forms and their relation to transsulfuration metabolites in a large, population-based study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:131–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hustad S, McKinley MC, McNulty H, et al. Riboflavin, flavin mononucleotide, and flavin adenine dinucleotide in human plasma and erythrocytes at baseline and after low-dose riboflavin supplementation. Clin Chem. 2002;48:1571–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anderson BB, Saary M, Stephens AD, Perry GM, Lersundi IC, Horn JE. Effect of riboflavin on red-cell metabolism of vitamin B6. Nature. 1976;264:574–5. doi: 10.1038/264574a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Figueiredo JC, Levine AJ, Grau MV, et al. Vitamins B2, B6, and B12 and risk of new colorectal adenomas in a randomized trial of aspirin use and folic acid supplementation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:2136–45. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rivlin RS. Riboflavin metabolism. N Engl J Med. 1970;283:463–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197008272830906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Komatsu S, Yanaka N, Matsubara K, Kato N. Antitumor effect of vitamin B6 and its mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1647:127–30. doi: 10.1016/s1570-9639(03)00076-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Matsubara K, Komatsu S, Oka T, Kato N. Vitamin B6-mediated suppression of colon tumorigenesis, cell proliferation, and angiogenesis (review) J Nutr Biochem. 2003;14:246–50. doi: 10.1016/s0955-2863(03)00009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schroecksnadel K, Frick B, Winkler C, Fuchs D. Crucial role of interferon-gamma and stimulated macrophages in cardiovascular disease. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2006;4:205–13. doi: 10.2174/157016106777698379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Friso S, Jacques PF, Wilson PW, Rosenberg IH, Selhub J. Low circulating vitamin B(6) is associated with elevation of the inflammation marker C-reactive protein independently of plasma homocysteine levels. Circulation. 2001;103:2788–91. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.23.2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Halsted CH, Villanueva JA, Devlin AM, Chandler CJ. Metabolic interactions of alcohol and folate. J Nutr. 2002;132:2367S–72S. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.8.2367S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lumeng L, Li TK. Vitamin B6 metabolism in chronic alcohol abuse. Pyridoxal phosphate levels in plasma and the effects of acetaldehyde on pyridoxal phosphate synthesis and degradation in human erythrocytes. J Clin Invest. 1974;53:693–704. doi: 10.1172/JCI107607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Slattery ML, Schaffer D, Edwards SL, Ma KN, Potter JD. Are dietary factors involved in DNA methylation associated with colon cancer? Nutr Cancer. 1997;28:52–62. doi: 10.1080/01635589709514553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fredriksen A, Meyer K, Ueland PM, Vollset SE, Grotmol T, Schneede J. Large-scale population-based metabolic phenotyping of thirteen genetic polymorphisms related to one-carbon metabolism. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:856–65. doi: 10.1002/humu.20522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ulrich CM, Neuhouser M, Liu AY, et al. Mathematical modeling of folate metabolism: predicted effects of genetic polymorphisms on mechanisms and biomarkers relevant to carcinogenesis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:1822–31. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]