Abstract

The serine threonine kinase Raf-1 plays a protective role in many cell types, but its function in pancreatic β-cells has not been elucidated. In the present study, we examined whether primary β-cells possess Raf-1 and tested the hypothesis that Raf-1 is critical for β-cell survival. Using reverse transcriptase-PCR, Western blot, and immunofluorescence, we identified Raf-1 in human islets, mouse islets, and in the MIN6 β-cell line. Blocking Raf-1 activity using a specific Raf-1 inhibitor or dominant-negative Raf-1 mutants led to a time- and dose-dependent increase in cell death, assessed by real-time imaging of propidium iodide incorporation, TUNEL, PCR-enhanced DNA laddering, and Caspase-3 cleavage. Although the rapid increase in apoptotic cell death was associated with decreased Erk phosphorylation, studies with two Mek inhibitors suggested that the classical Erk-dependent pathway could explain only part of the cell death observed after inhibition of Raf-1. An alternative Erk-independent pathway downstream of Raf-1 kinase involving the pro-apoptotic protein Bad has recently been characterized in other tissues. Inhibiting Raf-1 in β-cells led to a striking loss of Bad phosphorylation at serine 112 and an increase in the protein levels of both Bad and Bax. Together, our data strongly suggest that Raf-1 signaling plays an important role regulating β-cell survival, via both Erk-dependent and Bad-dependent mechanisms. Conversely, acutely inhibiting phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase Akt had more modest effects on β-cell death. These studies identify Raf-1 as a critical anti-apoptotic kinase in pancreatic β-cells and contribute to our understanding of survival signaling in this cell type.

A reduction in pancreatic β-cell survival is a critical pathogenic event in type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes, and rare monogenic forms of the disease. Moreover, increased β-cell death has been implicated in the failure of clinical islet transplantation (1–3). Several kinases have been investigated for their possible roles in β-cell survival, with PI3 3-kinase and Akt receiving the most attention to date (4–8). Transgenic mice that overexpress constitutively active Akt in their β-cells are protected against streptozotocin-induced diabetes (9, 10) and overexpression of constitutively active Akt protects INS-1 cells from free fatty acid-induced apoptosis (11). However, mice with an 80% reduction in islet Akt activity did not show increased apoptosis or reduced β-cell mass (12, 13), suggesting the possibility that other kinases may contribute to β-cell survival.

The Ras-Raf-mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade mediates pro-survival signals in many cell types. However, this signaling pathway remains understudied in pancreatic β-cells. Members of this pathway are found in human and mouse islets, as well as in β-cell lines (14–17). The Raf kinase is a critical hub in this cascade, as it integrates multiple upstream signals and controls several downstream effectors. All three Raf isoforms (A-Raf, B-Raf, and C-Raf/Raf-1) share a common structure but they differ in their expression profile, regulation, and the extent to which they depend on Erk for their biological action (18). Of the three Raf isoforms, Raf-1 appears to be preferentially involved in anti-apoptotic signaling, rather than being specific for the control of proliferation (19, 20).

Raf-1 activity is controlled by its phosphorylation status and subcellular localization (21–24). Raf-1 is recruited to the plasma membrane by Ras, a guanine-nucleotide-binding protein (24–26). Subsequent to Raf-1 activation in the plasma membrane, Raf-1 is known to physically associate with and activate Mek, an upstream kinase activator of Erk kinases (27–29). Thus, Raf-1 is a link between Ras and Erk. The role of Erk in β-cell survival remains a controversial topic, with some studies supporting an anti-apoptotic role (17, 30–32) and others suggesting a requirement for Erk in β-cell apoptosis (14, 32, 33). A body of literature from other cell types also suggests that Raf-1 may have a unique pro-survival effect independent of Erk activity (19, 20). Raf-1 knock-out mice die around mid-gestation with increased apoptosis in several tissues (19). Surprisingly, the activity and levels of both Mek and Erk are normal, suggesting the ability of the other Raf isoforms to compensate for Raf-1 or that Raf-1 may promote survival independent of Erk. This Erk-independent pathway appears to involve the Bcl-2-mediated targeting of Raf-1 to the mitochondria where Raf-1 phosphorylates Bad. This event prevents Bad from triggering the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway (34, 35). Whether this function of Raf-1 plays a role in β-cell survival is unclear.

The objective of the present study was to examine whether Raf-1 is present in β-cells and to determine whether this kinase plays a role in β-cell survival. We observed that a small molecule Raf-1 inhibitor and dominant-negative Raf-1 mutants caused β-cell apoptosis. Blocking Raf-1 signaling led to the dephosphorylation of Bad in addition to the inactivation of Erk. These findings are the first to implicate Raf-1 in β-cell survival.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

The following inhibitors were obtained from Cal-biochem (La Jolla, CA): a Raf-1 inhibitor (Raf-1i; also known as GW5074; 5-iodo-3-[(3,5-dibromo-4-hydroxyphenyl)methylene]-2-indolinone), two different Mek inhibitors, PD98059 (2′-amino-3′-methoxyflavone) and UO126 (1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis(2-aminophenylthio)butadiene), the PI 3-kinase inhibitor LY294002 (2-(4-morpholinyl)-8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one), as well as two Akt inhibitors, Akt Inhibitor VII (TATAkti) and Akt Inhibitor VIII (1,3-dihydro-1-(1-((4-(6-phenyl-1H-imidazo[4,5-g]quinoxalin-7-yl)phenyl)methyl)-4-piperidinyl)-2H-benzimidazol-2-one (Akti-1/2). Other reagents were from Sigma. Unless otherwise indicated, doses of specific inhibitors were expected to be maximally effective based on their known IC50 values. For the Raf-1 inhibitor, we used concentrations within the values reported to block the kinase in intact cells (5–100 μM) (36, 37).

Cell Culture

Primary islets were isolated from 3–4-month-old C57Bl6/J mice (Jax, Bar Harbor, MA) using collagenase and filtration as described previously (38). Human islets were provided through the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Centre for Human Islet Transplant and Beta-cell Regeneration, directed by Dr. Garth Warnock. Islets were cultured in 35 × 10-mm Nunc suspension dishes (Nalge, Rochester, NY) at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 media with 5 mM glucose (unless indicated otherwise). Media was supplemented with 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and brought to pH 7.4 with NaOH. MIN6 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 25 mM glucose with 10% penicillin/streptomyosin (Invitrogen).

Gene Expression Detection

Total RNA was isolated from mouse primary islets and MIN6 cells using the Qiagen RNeasy kit (Mississauga, ON). cDNA was reverse-transcribed using SuperScript III from Invitrogen. PCR amplification (in the linear range) was carried out using 1 cycle of 94 °C for 5 min, 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 45 s, and 1 cycle of 72 °C for 7 min. Primers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA): A-Raf (forward, 5′-AGCA-TCCAGGATCTGTCTGG-3′; reverse, 5′-ACCTGCATGAGGCTGGAGTC-3′), B-Raf (forward, 5′-GGCCAGGCTCTGTTCAATG-3′; reverse, 5′-CTCTTTGCTGAAGGGCATCT-3′), and C-Raf/Raf-1 (forward, 5′-AGTTAGAGCCGAGCGGACTT-3′; reverse, 5′-AGTCCAAAGCCATTGCTGAT-3′).

Immunofluorescence Imaging

Immunofluorescence analysis of endogenous Raf-1 in dispersed islet β-cells and MIN6 cells was performed as described (39, 40) using a Zeiss 200M microscope equipped with a ×100 (1.45 numerical aperture) objective. Cells were fixed in fresh 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, permeabilized using 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min, and blocked using 10% normal goat serum. Raf-1 was detected using a rabbit polyclonal primary antibody (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA) and goat secondary antibody conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). Primary antibodies to insulin (Linco Research, St. Charles, MO) were detected with goat secondary antibodies conjugated to Texas Red (Jackson ImmunoResearch). 1 μg of DNA of Raf-1-GFP, Raf-151–131-GFP, Raf-151–220-GFP, kindly provided by Dr. Tamás Balla (Endocrinology and Reproduction Research Branch, National Institutes of Health), and 1 μg of DNA of mitochondria-targeted dsRed vector, kindly provided by Dr. Heidi M. McBride (University of Ottawa), were co-transfected into MIN6 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) for 24 h before adding 0.1 μg/ml of Hoechst 33342 DNA dye (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen) and performing live cell imaging. Pearson correlation between Raf-1-Gfp fusion proteins and DsRed-Mito or Hoescht (nucleus) was calculated using SlideBook 4.2 software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO).

Analysis of Programmed Cell Death

An incubated, high-throughput imaging system (KineticScan, Cellomics Inc., Pittsburgh, PA) was used to measure cell death in MIN6 cells and primary mouse dispersed β-cells treated with various inhibitors. Cell death was counted in real-time by imaging propidium iodide incorporation into nuclear DNA. This dye only crosses the plasma membrane of dying cells. Primary mouse islets were dispersed (~5,000–10,000 cells/well) 24 h after isolation and allowed to attach in a 96-well Viewplate (Packard, Meriden, CT), centrifuged for 30 s at 200 × g, and left to grow overnight before adding treatments. MIN6 cells at ~75% confluence (~10,000–15,000 cells/well) were seeded in a 96-well Viewplate and left to grow overnight and washed before adding treatment media. Treatments were prepared in serum-free media containing 2.5 ng/μl of propidium iodide. Data analysis was performed using a macro written by Dr. Dan Luciani in Microsoft Excel. Three independent cultures were analyzed per imaging run and each experimental run was performed on at least three different days.

The terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase biotin-dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) technique was also employed to measure programmed cell death. MIN6 cells were seeded onto glass coverslips at 75% confluence and ~20 human or mouse islets were dispersed per coverslip. Cells were incubated overnight before being treated for 24 h. After incubation with the appropriate treatments, cells were washed 3 times with ice-cold phosphate-buffered-saline (PBS) before being fixed with fresh 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 10 min, then permeabilized for 10 min with 0.1% Triton X-100 and blocked with DAKO Protein Block Serum-Free (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) for 30 min. The TUNEL in situ cell death detection kit was used (Roche Applied Science, Laval, QC) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were mounted in Vectashield medium with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA). Islet apoptosis was also measured using a previously described variation of a PCR-enhanced DNA laddering protocol modified for use in small numbers of islets (13, 41).

Raf-1 Fusion Proteins Over-expression

Raf-1 fusion proteins (Raf-1-Gfp, Raf-151–131-Gfp, and Raf-151–220-Gfp) were transiently overexpressed in MIN6 cells under the control of the cytomegalovirus promoter. Raf-151–131-Gfp and Raf-151–220-Gfp displayed a dominant-negative effect on Erk activity as previously described (42)(see “Results”). Enhanced Gfp (EGfp) cDNA was transfected as a control. Forty-eight hours after transfection using Lipofectamine 2000, MIN6 cells were washed twice with PBS (minus MgCl2 and CaCl2) before adding trypsin, and resuspending the cell pellet in PBS with 2% fetal bovine serum. To ensure that only cells containing Raf-1 fusions were studied, Gfp-positive cells were sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (BD FACS Vantage SE/DIVA). The resulting cells (~200,000 cells) were washed twice with ice-cold PBS before adding lysis buffer with protease inhibitor (Cell Signaling). Whole cell lysates were freeze-thawed before being subjected to Western blotting (see below).

Protein Detection by Immunoblot

MIN6 cells, human islets, or mouse islets were washed twice after treatments with ice-cold PBS before adding cell lysis buffer with protease inhibitor mixture (Cell Signaling). Whole cell lysates were freeze-thawed twice and protein concentrations were determined using the BCA protein assay (Pierce). Protein lysates (30–40 μg) were subjected to PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. Membranes were then blocked with I-block solution (Tropix, Bedford, MA), washed, and probed with primary antibodies. Primary antibodies against Erk1/2, phosphorylated Erk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), Bad, phosphorylated Bad (Ser112), Bax, Bcl-2, phosphorylated Ask-1 (Thr845), Ask-1, and cleaved Caspase-3 were from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). Primary mouse monoclonal antibody to β-Actin was from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO). Primary rabbit monoclonal antibody to Chop/Gadd 153 was from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA). Secondary antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling. Immunodetection was performed with ECL Western Blotting Detection Reagents from Amersham Biosciences. Densitometric analysis was performed using Photoshop (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA).

Insulin Secretion Analysis in Islet Perifusion and Conditioned Media in MIN6 Cells

Mouse islets were cultured overnight after isolation after which groups of 100 size-matched islets were suspended with Cytodex microcarrier beads (Sigma) in 300-μl plastic chambers of an Acusyst-S perifusion apparatus (Endotronics, Minneapolis, MN). Islets were perifused at 37 °C and 5% CO2 at 0.5 ml min−1 with a Krebs-Ringer buffer containing: 129 mM NaCl, 5 mM NaHCO3, 4.8 mM KCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 10 mM HEPES, 3 mM glucose, and 5 g/liter radioimmunoassay grade bovine serum albumin (Sigma). Prior to sample collection, islets were equilibrated under basal (3 mM glucose) conditions for 1 h. We also collected conditioned media from MIN6 cells treated with Raf-1i, Akti-1/2, UO126, and PD98059 for 3 h. Insulin secretion was measured using a radioimmunoassay (Rat Insulin RIA Kit, Linco Research, St. Charles, MO).

Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as mean ± S.E. Statistical significance was determined using unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t tests calculated in Excel. Results were considered to be statistically significant when p < 0.05. All human islet experiments were replicated on islets from at least 3 donors.

RESULTS

Identification of Raf-1 Kinase in β-Cells

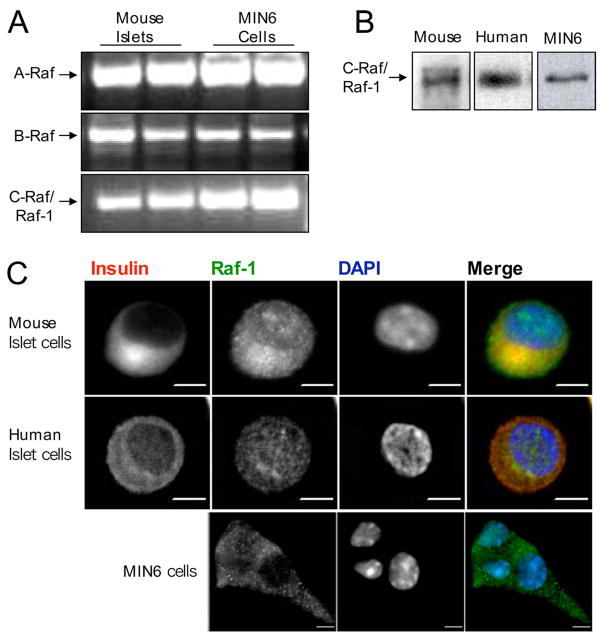

Despite its potential importance in pro-survival signaling, the presence and sub-cellular localization of Raf-1 have not been directly assessed in pancreatic β-cells to our knowledge. First, we examined the gene expression of the three members of the Raf family kinase in MIN6 cells and mouse islets by reverse transcriptase-PCR and determined that all three isoforms were present (Fig. 1A). B-Raf and Raf-1 were previously identified in human islets by immunohistochemistry and immunoblotting, respectively (15). Due to the predominant anti-apoptotic role of Raf-1, we focused on this isoform and confirmed its protein expression in primary mouse and human islets and MIN6 cells using Western blotting (Fig. 1B). Although these results demonstrate that Raf-1 is present in islets, they do not provide information regarding the β-cell-specific expression or subcellular localization of this protein. To address this, we used immunofluorescence imaging. We observed that endogenous Raf-1 is expressed in dispersed β-cells from both mouse and human islets and in MIN6 cells. In primary islet cells, Raf-1 was localized in the cytoplasm and the nucleus, which was consistent with studies in other cell types (43). In MIN6 cells, we found Raf-1 immunoreactivity primarily in the cytoplasm, although some cells also showed nuclear staining. Together these findings indicate that Raf-1 is present in primary and transformed pancreatic β-cells.

FIGURE 1. Expression of Raf isoforms in pancreatic β-cells.

A, total RNA was extracted from mouse islets and MIN6 cells and gene expression levels were analyzed by semi-quantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR (n = 3). B, Raf-1 protein expression was detected in human and mouse islets as well as in the MIN6 cell line using Western blot (n = 3). C, immunofluorescence imaging of Raf-1 in mouse β-cells, human β-cells, and MIN6 dispersed islet cells showing Raf-1 localization in the cytoplasm and the nucleus (>1000 cells examined). Scale bar, 5 μm. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Inhibition of Endogenous Raf-1 Signaling Induces β-Cell Apoptosis

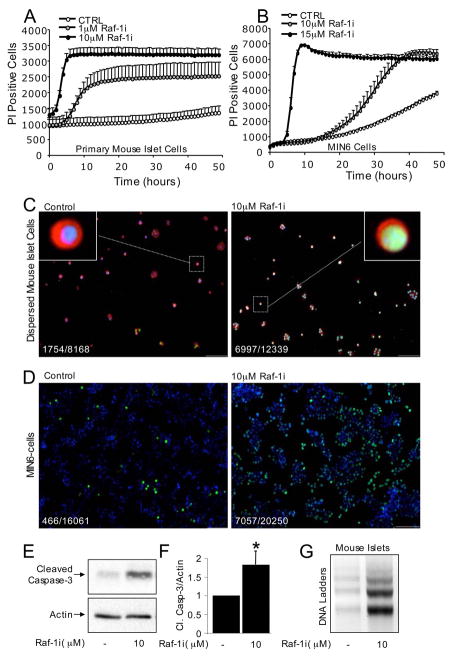

After establishing that Raf-1 is expressed in β-cells, we examined the consequences of blocking endogenous Raf-1 signaling in this cell type using a commercially available Raf-1 inhibitor (Raf-1i) reported to be highly selective for Raf-1 (100 times more selective compared with a panel of related kinases) (44). We hypothesized that disrupting Raf-1 signaling may lead to β-cell death. Indeed, inhibiting Raf-1 signaling in both primary mouse islet cells and transformed MIN6 β-cells increased cell death in a time- and dose-dependent manner as determined by the real-time monitoring of propidium iodide incorporation (Fig. 2, A and B). A massive increase in apoptotic β-cell death in the presence of the Raf-1 inhibitor was confirmed in MIN6 cells using the fluorescent TUNEL technique (Fig. 2, C and D). A similar increase in apoptosis was observed when TUNEL was combined with insulin staining in primary mouse islet cells (Fig. 2C) and human islet cells (data not shown). The Raf-1 inhibitor also increased Caspase-3 cleavage in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Figs. 2E and 7, C and E), suggesting that a reduction in Raf-1 kinase activity leads to the activation of this executioner Caspase. We further confirmed that Raf-1i evokes apoptotic programmed cell death using DNA ladder analysis on mouse islets (Fig. 2G) and MIN6 cells (data not shown). Together, these results clearly demonstrate that blocking Raf-1 kinase triggers a rapid and robust apoptotic response in primary human and mouse β-cells and in the MIN6 β-cell line. Thus, endogenous Raf-1 activity appears to be essential for β-cell survival.

FIGURE 2. Inhibition of endogenous Raf-1 signaling in primary mouse islet cells and MIN6 cells causes β-cell death.

Rapid increase in propidium iodide (PI) incorporation in dispersed mouse islet cells (A) and MIN6 cells (B) treated with the specific inhibitor of Raf-1 kinase, Raf-1i (n = 9). Raf-1i increases β-cell death in a dose-and time-dependent manner. Raf-1i also caused β-cell apoptosis assessed by TUNEL staining of mouse islet β-cells (C) and MIN6 cells within 24 h (D). C, dispersed mouse β-cells stained for insulin are red, TUNEL positive cells are green, and cell nuclei stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole are blue. D, TUNEL-positive MIN6 cells are green and nuclei are blue. TUNEL staining experiments were repeated independently with similar results using dispersed human and mouse islets (≥8,168 cells examined for each condition) and MIN6 cells (≥16,061 cells for each condition). The ratio of TUNEL positive cells/total cells examined is shown as an inset. E, cleaved Caspase-3 protein levels in MIN6 cells treated with Raf-1i for 6 h (n = 3). F, quantification of cleaved Caspase-3 protein levels corrected to control. G, Raf-1i induces DNA laddering in intact mouse islets (n = 3). Asterisk denotes significant difference (p < 0.05) between the control and treatment.

FIGURE 7. The relative roles of Raf-1 and PI 3-kinase/Akt signaling on ER stress and in β-cell apoptosis.

Rapid increase in propidium iodide incorporation in dispersed mouse islet cells (A) and MIN6 cells (B) treated with specific inhibitors of Raf-1 kinase (Raf-1i), PI 3-kinase (LY294002), or Akt kinase (Akti-1/2 and TATAkt-in). Like Raf-1i, LY294002 and Akti-1/2 increased β-cell death in a dose- and time-dependent manner, suggesting that all three kinases play a role in β-cell survival (n = 6). C, effects of Raf-1i and Akti-1/2 on the expression of CHOP, an ER stress marker, and cleavage of caspase-3 in MIN6 cells treated for 3 h (n = 3). C, phosphorylated and total Erk and phosphorylated (Ser112) Bad and total Bad levels in MIN6 cells treated with Raf-1i and Akti-1/2 for 3 h (n = 3). Quantification of Chop/β-Actin ratio (D) and cleaved Caspase-3/β-Actin ratio (E) normalized to control. F, quantification of Bad Ser112/total Bad protein ratio normalized to the control. G, quantification of total Bad/β-Actin ratio corrected to control. H, quantification of phosphorylated and the total Erk level ratio normalized to control. Asterisk denotes a significant difference (p < 0.05) between the control and treatment.

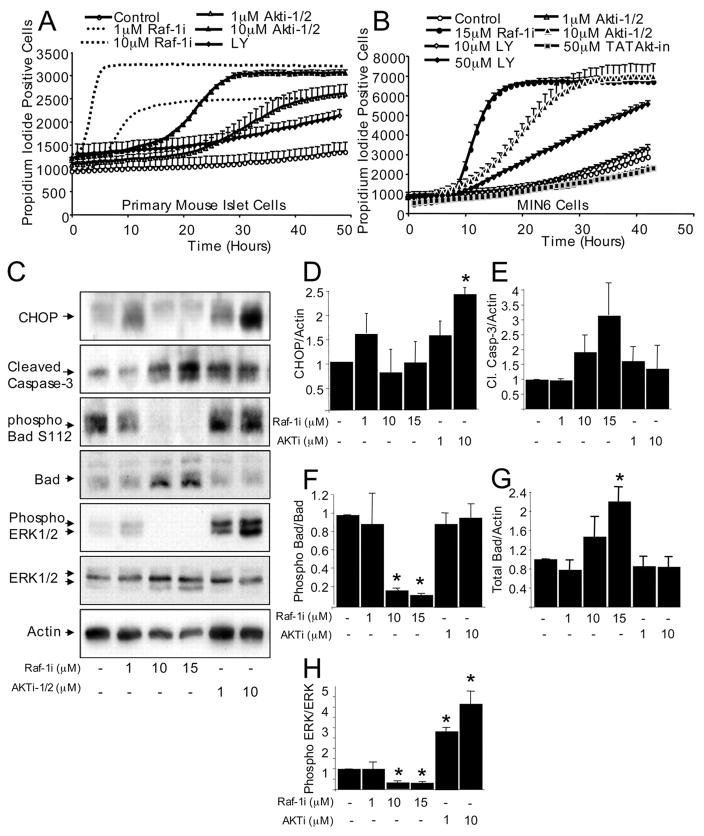

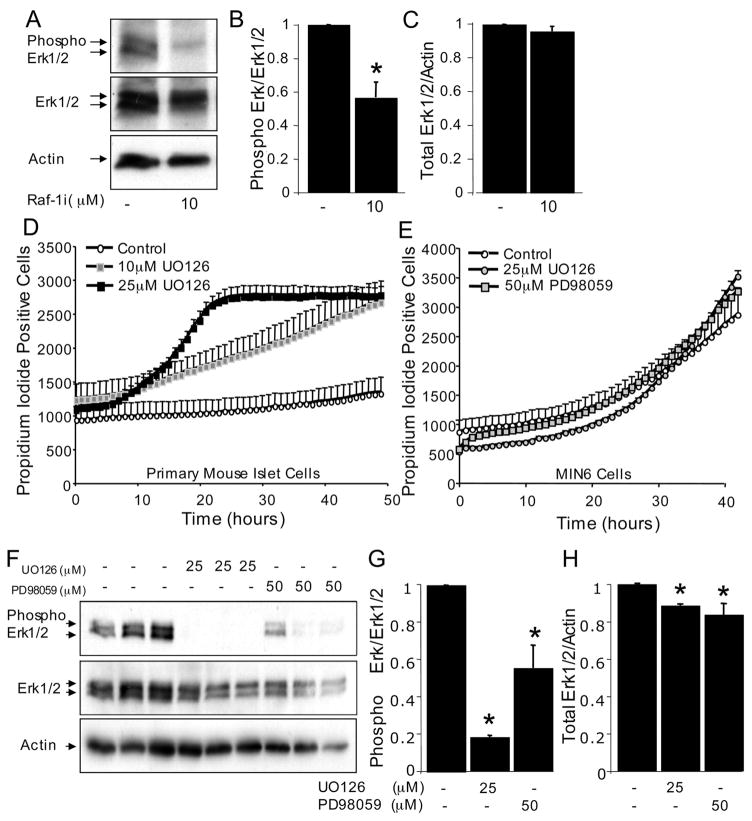

Raf-1 Inhibitor Reduces Erk and Bad Phosphorylation

The mechanism by which Raf-1 inhibition caused apoptosis was investigated next, using MIN6 cells as a model. We first examined the phosphorylation and activation state of Erk, the canonical downstream target of Raf-1. Western blot analysis revealed that Raf-1i decreased Erk phosphorylation, but did not alter the total levels of Erk protein (Fig. 3, A–C). Mek is known to mediate the effects of Raf-1 on Erk phosphorylation. To test the hypothesis that endogenous Mek serves an anti-apoptotic role in β-cells, cell death in the presence of two Mek inhibitors, UO126 and PD98059, was examined. These inhibitors had modest apoptosis-inducing effects in MIN6 cells and in primary mouse islet cells (Fig. 3, D–E), suggesting that a component of the pro-survival actions of Raf-1 may be mediated via Mek and Erk. However, the effects of the Mek inhibitors were less rapid and robust than those observed with the Raf-1 inhibitor. As expected, both Mek inhibitors reduced Erk phosphorylation levels (Fig. 3, F–H). Together, these results implicate Mek and Erk in β-cell survival.

FIGURE 3. Roles of Erk and Mek in Raf-1 inhibitor-induced β-cell death.

A, phosphorylated and total Erk levels in MIN6 cells treated with Raf-1i for 6 h (n = 3). B, quantification of phosphorylated Erk to total Erk protein levels normalized to control. C, quantification of total Erk/β-Actin protein levels normalized to control. Moderate increase in propidium iodide incorporation in dispersed mouse islet cells (D) and MIN6 cells (E) treated with Mek inhibitors, UO126 and PD98059. F, phosphorylated and total Erk levels in MIN6 cells treated with UO126 and PD98059 for 3 h (n = 3). G, quantification of phosphorylated Erk to total Erk protein levels normalized to control. H, quantification total Erk/β-Actin ratio normalized to control. Asterisk denotes significant difference (p < 0.05) between the control and treatment.

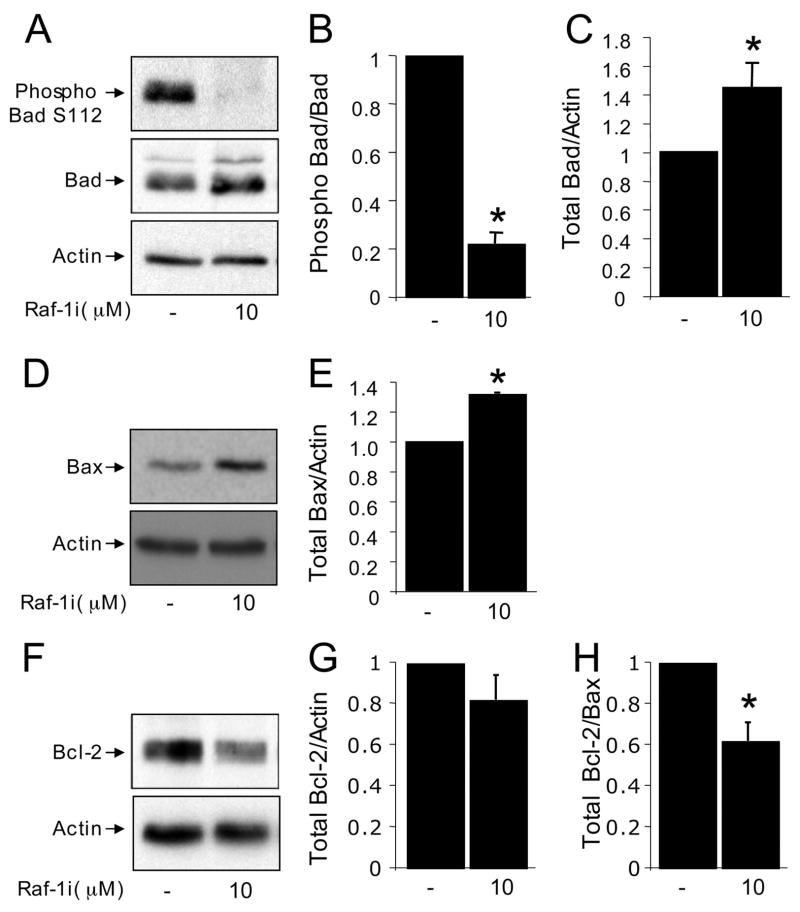

The observation that the modest cell death subsequent to inhibiting Mek could not fully account for the effects of the Raf-1 inhibitor led us to examine alternative pathways. Several recent studies have suggested that the pro-survival effects of Raf-1 can be mediated by phosphorylating Bad on serine 112, which contributes to the inactivation and sequesterization of this pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member by 14-3-3 proteins (34, 36). Thus, we hypothesized that inhibition of Raf-1 signaling might reduce Bad phosphorylation. Indeed, a marked and rapid reduction in Bad phosphorylation was observed in β-cells treated with the Raf-1 inhibitor (Fig. 4, A and B). Studies in other cell types have demonstrated that when Bad is dephosphorylated, it migrates to the mitochondria where it can dimerize with Bcl-XL (45), leading to the release of Bax, an initiator of apoptosis. We found that Raf-1 inhibitor increased the protein expression of both Bad and Bax (Fig. 4, B–E). Because the ratio of Bcl-2 to Bax is thought to determine sensitivity to apoptosis, we also analyzed whether Raf-1i affected Bcl-2 levels. Indeed, the ratio of Bax to Bcl-2 was increased (Fig. 4, F–H). Together, these data further implicate Raf-1 in the control of β-cell apoptosis and point to an emerging Bad-dependent pathway as a contributing mechanism in this action.

FIGURE 4. Effects of Raf-1 inhibitor on Bad, Bcl-2, and Bax.

A, phosphorylated Bad (Ser112) and total Bad in MIN6 cells treated with Raf-1i for 6 h (n = 3). B, quantification of the ratio of phosphorylated Bad Ser112 to total Bad protein (normalized to control). C, quantification of total Bad/β-Actin protein ratio normalized to control. D, Raf-1i increased Bax protein levels in MIN6 cells treated for 6 h (n = 3). E, quantification of total Bax/β-Actin protein ratio normalized to control. F, Bcl-2 protein levels/β-Actin protein normalized to the control (n = 3). G, quantification of total Bcl-2/β-Actin protein levels normalized to control. H, Bcl-2/Bax ratio. Asterisk denotes significant difference (p < 0.05) between the control and treatment.

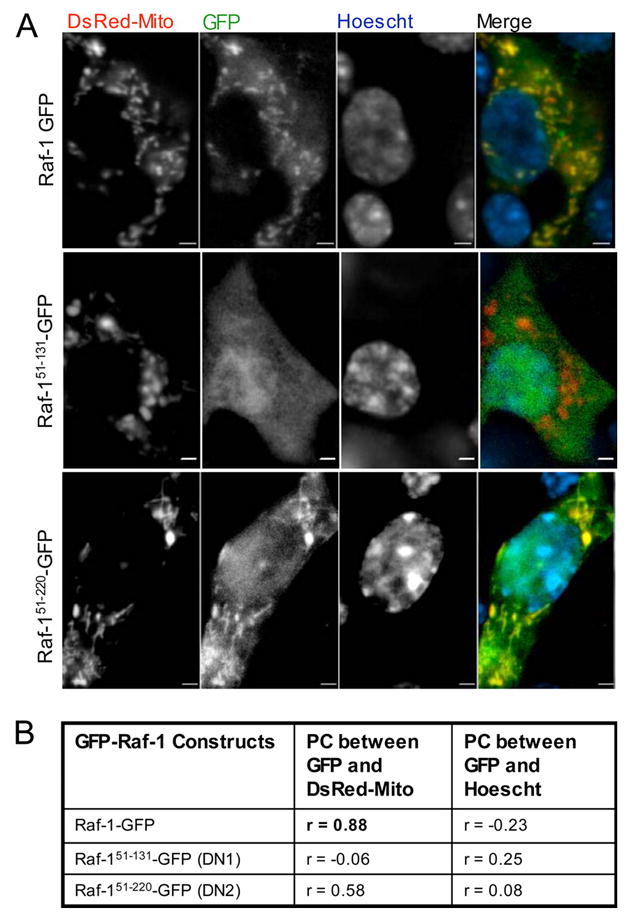

Effects of Dominant-negative Raf-1 on β-Cell Death

Given the caveats inherent to all pharmacological inhibitors, we also employed Raf-1-Gfp fusion proteins to inhibit or enhance Raf-1 signaling in β-cells. First, we confirmed the overexpression and examined the localization of three different Raf-1-Gfp fusion proteins using live cell imaging in MIN6 cells. The overexpressed full-length Raf-1-Gfp fusion protein was found in the cytoplasm and at the mitochondria, but not in the nucleus (Fig. 5A). We also utilized two dominant-negative truncated mutants of Raf-1, Raf-151–131-Gfp and Raf-151–220-Gfp, both of which have been previously described to inhibit Raf-1 signaling (42). We observed that Raf-151–220-Gfp was localized in the cytoplasm and mitochondria and partially in the nucleus. The short form of Raf-151–131-Gfp was mainly localized in the cytoplasm and the nucleus (Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5. Localization of Raf-1-Gfp fusion proteins in MIN6 cells.

Widefield, deconvolution fluorescence imaging of Raf-1-Gfp fusion proteins and mitochondrial-targeted red fluorescent protein (DsRed-Mito) co-transfected into MIN6 cells. A, DsRed-Mito colocalizes strongly with Raf-1-Gfp, modestly with Raf-151–220-Gfp, but not with Raf-151–131-Gfp. B, Pearson correlation between Raf-1-Gfp fusion proteins and DsRed-Mito or Hoechst DNA dye (nucleus) were calculated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Scale bar, 2 μm.

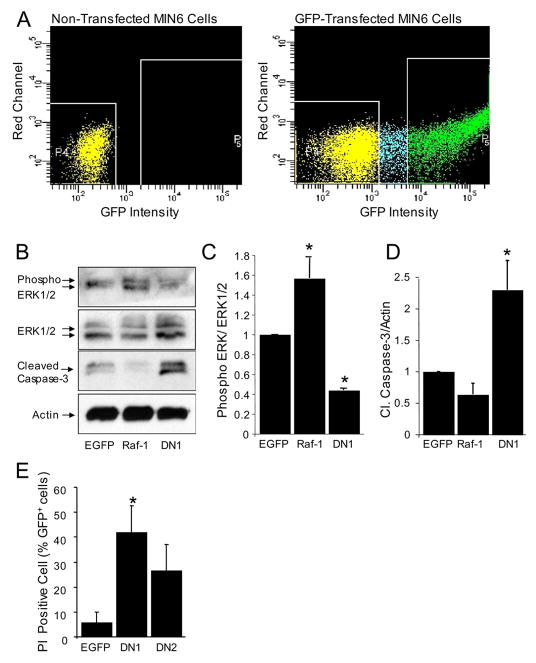

To determine the effect of overexpressing Raf-1 mutants in β-cell death, we measured Caspase-3 cleavage 24 h after transfection. In initial experiments with about 10% transfection efficiency, we observed an increase of ~20% in Caspase-3 cleavage compared with control (data not shown). Thus, to enrich our Raf-1-Gfp-expressing MIN6 cell population, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS; Fig. 6A) was employed prior to measuring Erk phosphorylation and caspase-3 cleavage. We observed that overexpression of Raf-1-Gfp increased Erk phosphorylation and modestly reduced Caspase-3 cleavage (Fig. 6, B–D), suggesting the possibility that overexpression of Raf-1 may protect β-cells from apoptosis. Conversely, overexpression of dominant-negative Raf-1 mutants significantly reduced Erk phosphorylation and increased the expression of cleaved Caspase-3 compared with control cells transfected with EGfp alone. Moreover, we observed an increase in propidium iodide incorporation in cells expressing dominant-negative Raf-1 mutants (Fig. 6E). Overall, our data from experiments using the pharmacological inhibitor and Raf-1 mutants point to Raf-1 as a critical pro-survival kinase in the β-cell.

FIGURE 6. Expressed Raf-1-Gfp fusion proteins inhibit Raf-1-mediated Erk activation and induces MIN6 cells β-cell death.

A, sample FACS scatter plots showing non-GFP expressing MIN6 cells and Gfp-positive cells. B, phosphorylated Erk and cleaved Caspase-3, total Erk, and β-Actin in FACS-enriched Gfp-positive MIN6 cells (n = 3). C, quantification of phosphorylated Erk/total Erk protein ratio normalized to control. D, quantification of cleaved Caspase-3 protein/β-Actin ratio normalized to control. E, expression of dominant-negative Raf-1 fusion proteins caused an increased in propidium iodide incorporation in MIN6 cells. Asterisk denotes significant difference (p < 0.05) between the control and treatment.

Roles and Mechanisms of Raf-1 and PI 3-Kinase/Akt Signaling in β-Cell Apoptosis

Raf-1, Erk, PI 3-kinase, and Akt are vital components of numerous pro-survival signaling cascades in many cell types. Among these kinases, the PI 3-kinase and Akt have received the majority of the attention in the β-cell. To assess in parallel the relative importance of these kinases in the context of β-cell survival, we measured cell death in real-time in the presence of specific inhibitors in primary mouse islet cells and MIN6 cells. PI 3-kinase was inhibited using LY294002. Two different Akt inhibitors were employed (TATAkt-in and Akti-1/2). In the presence of LY294002, an increase in the number of propidium iodide-positive cells was detected (Fig. 7, A and B), supporting the notion that the PI 3-kinase is important for β-cell survival (5, 46). Inhibiting Akt caused an increase in β-cell death, but to a lesser extent compared with the Raf-1 inhibitor (Fig. 7, A and B). The increase in apoptotic β-cell death in the presence of Raf-1i and Akti-1/2 was associated with the cleavage of Caspase-3 (Fig. 7C). Recent studies have implicated ER-stress response in β-cell apoptosis (47–49) and pointed to Akt as a critical suppressor of this form of programmed cell death (50). Treatment of MIN6 cells with Akti-1/2 caused a dose-dependent increase in Chop, a well established marker of ER stress (Fig. 7C). In contrast, Raf-1i induced only modest Chop expression at low but not at high concentrations at this time point (Fig. 7C). We also detected a trend toward increased Chop levels in isolated human islets treated with Raf-1i (data not shown). Together these experiments demonstrate that multiple kinase cascades play important roles in β-cell survival.

Next we examined the mechanisms involved in pro-survival signaling downstream of Akt and Raf-1 and assessed cross-talk between these signaling networks in the β-cell. The Raf-1 kinase has been previously identified as a point of cross-talk between Akt and Erk signaling cascades (51). Although it has been postulated that both the PI 3-kinase/Akt and Raf-1/Erk signaling cascades are activated simultaneously to magnify cell survival signals, depending on the cell context, Akt can negatively affect Raf-1 activity by phosphorylation at Ser259 (52). In the presence of Akti-1/2, this negative regulation appears to be attenuated resulting in an increase in Erk phosphorylation (Fig. 7, C and H). This suggests the possibility that a compensatory mechanism can be up-regulated to maintain β-cell survival under conditions where Akt is inhibited. Interestingly, unlike Raf-1i, Akti-1/2 did not alter Bad phosphorylation at Ser112 or total Bad protein levels (Fig. 7, C, F, and G), pointing to a difference in the targets of these two kinases. The ability of Akt to negatively regulate Raf-1 may explain why we see a robust and enhanced β-cell death in the presence of Raf-1i and only moderate death in the presence of Akt inhibitors.

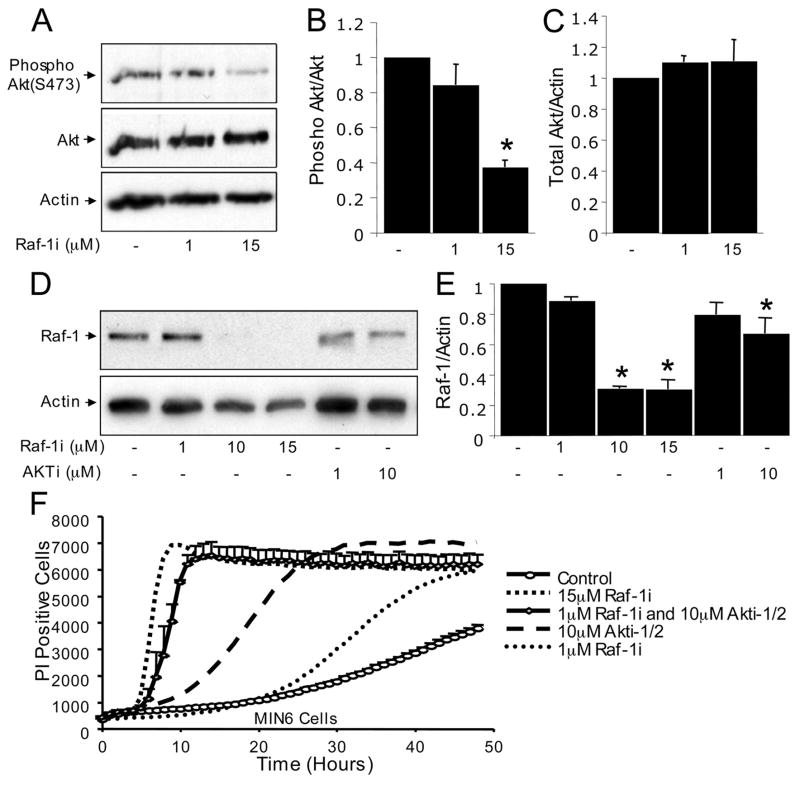

It is not clear whether inhibition of Raf-1 kinase signaling directly affects Akt activity. Raf-1 gene ablation in the heart did not alter Akt phosphorylation or total protein level (20). Interestingly, MIN6 cells treated with Raf-1i had reduced Akt phosphorylation (Fig. 8, A–C). Therefore, Raf-1 kinase may affect Akt directly or indirectly through an upstream kinase. We also examined the autoregulatory effects of blocking Raf-1 signaling. Raf-1i, as well as Akti-1/2 reduced the apparent total Raf-1 protein level, supporting the notion that Raf-1 signaling can exert positive feedback on itself (53). These results strongly suggest important functional interactions between Raf-1- and Akt-dependent signaling networks in β-cells.

FIGURE 8. Raf-1 inhibitor reduces Akt activity and Raf-1 protein levels.

A, phosphorylated Akt (Ser473) and total Akt in MIN6 cells treated with Raf-1i for 3 h (n = 3). B, quantification of phosphorylated Akt (Ser473) and total Akt protein levels normalized to the control. C, quantification of total Akt normalized to the control. D, Raf-1i and Akti-1/2 both reduced total Raf-1 protein levels in MIN6 cells. E, quantification as shown (n = 3). Note that this is the same β-Actin loading control shown in Fig. 7C. F, additive effects of blocking both Raf-1 and Akt on β-cell death. Rapid increase in propidium iodide (PI) incorporation in the presence of Raf-1i alone, or the combination of Raf-1i and Akti-1/2 MIN6 cells (n = 3). Asterisk denotes a significant difference (p < 0.05) between the control and treatment.

The suppression of Raf-1 protein levels presented an opportunity to address whether any of the known kinase-independent downstream targets of Raf-1 may be involved in β-cell survival. Aside from its ability to phosphorylate key downstream proteins such as Erk and Bad, Raf-1 has also been proposed to protect cells by serving as a scaffolding protein (54). Deletion of the Raf-1 gene has been associated with increased activity of apoptosis signaling kinase-1 (Ask-1), an event that does not require Raf-1 catalytic activity (55). Therefore, we assessed Ask-1 phosphorylation and total Ask-1 protein levels in our model (56). Although we were unable to detect Raf-1i-induced changes in Ask-1 phosphorylation at Thr845, we did observe a trend toward increased total Ask-1 expression at the highest dose of the inhibitor (data not shown). Overall, our data point to an important role for the kinase-dependent actions of Raf-1 in β-cell survival.

Effects of Combined Inhibition of Raf-1 and Akt on β-Cell Death

Given the differences in their downstream mechanisms, we hypothesized that simultaneously blocking both Raf-1 and Akt signaling would cause an additive effect on β-cell death. A massive increase in β-cell death was observed in the presence of both Raf-1 and Akt inhibitors when compared with individual treatments (Fig. 8F). These results further support the concept that the downstream anti-apoptotic targets of Raf-1 and Akt are distinct. Moreover, whereas inhibiting Akt alone results in an up-regulation of Erk phosphorylation, blocking Raf-1 negates this compensatory response. Collectively, these results identify Raf-1 as a critical kinase mediating β-cell survival and point to complex interactions with the Akt signaling system.

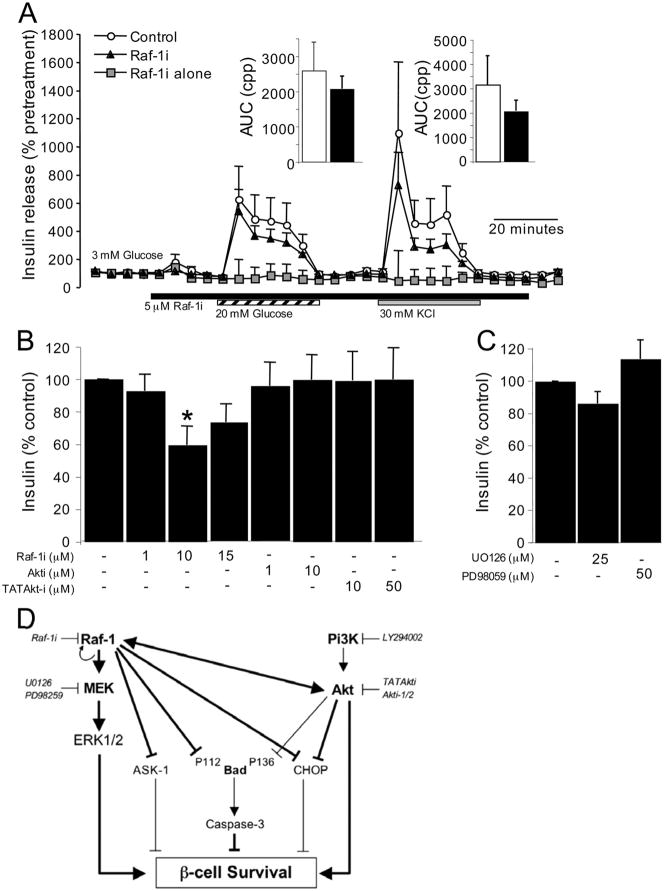

Effects of Raf-1 Signaling on Insulin Secretion

In addition to mediating β-cell survival, many kinases have been implicated in β-cell function. Thus, the effects of blocking Raf-1 signaling on basal and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion were examined. Using a perifusion approach to examine the dynamics of insulin secretion in primary mouse islets, we found that acute treatment with Raf-1i had a moderate, negative effect on both phases of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (Fig. 9A), prior to the appearance of any cell death (see Fig. 2). Similarly, inhibition of Raf-1 and Erk, but not Akt, resulted in modestly decreased insulin secretion from MIN6 cells (Fig. 9, B and C). Thus, Raf-1 and Erk appear to regulate both the survival and, to a lesser degree, the function of pancreatic β-cells.

FIGURE 9. Effects of Raf-1 inhibitor on insulin secretion in primary islets and MIN6 cells.

A, groups of 100 mouse islets were perifused with Krebs-Ringer buffer containing 3 mM glucose. Islets were exposed to 20 mM glucose (striped bar), 30 mM KCl (gray bar), in the presence or absence of 5 μM Raf-1i (black bar). Control islets (open circles) were exposed to glucose and KCl without Raf-1i. Islets treated with Raf-1i (closed triangle) were also exposed to glucose and KCl. Some islets were exposed to Raf-1i alone (gray squares) without glucose or KCl. Values are normalized to the pretreatment levels of insulin secretion to compensate for uneven numbers of islets in each column (n = 4). Area under the curve (AUC) was measured as the cumulative percent pre-treatment (cpp) and shown as insets. Insulin levels were measured in conditioned media of MIN6 cells treated with Raf-1i, Akti-1/2, UO126, and PD98059 for 3 h (n = 3) (B and C). Asterisk denotes a significant difference (p < 0.05) between the control and treatment. D, simplified diagram of the pro-survival Raf-1/Erk and PI 3-kinase/Akt signaling network in the β-cell. Major pro-survival factors in the β-cell activate a series of common signaling events that can be broadly divided into two arms, namely the PI 3-kinase/Akt and the Raf-1/Erk pathways. Activation of Raf-1 can lead to the induction of Erk activity or reduction of the pro-apoptotic effects of Ask-1, Bad, and Chop. Akt signaling prevents β-cell apoptosis in part through Foxo1, a negative regulator of β-cell survival (not shown) and by regulating other pro-apoptotic proteins (Bad and Chop). Raf-1 and Akt cross-talk at multiple levels and their signals are interdependent and coordinated to maintain β-cell survival. Interactions examined in the present study are illustrated by the thick lines, whereas interactions addressed by previous research are indicated by thin lines.

DISCUSSION

The objectives of the present study were to examine the expression of Raf-1 kinase in the β-cell, to assess whether its activity is critical for β-cell survival, and to determine the downstream targets that mediate this action. Our study had five major findings. First, we confirmed the presence and functional relevance of the Raf-1 kinase in primary pancreatic β-cells from both mouse and human islets, as well as in the MIN6 β-cell line. Second, we determined that inhibiting Raf-1 kinase activity results in a rapid and robust programmed cell death in both primary islets and the MIN6 β-cell line. Third, we determined that Raf-1 protects β-cells via both Erk-dependent and -independent modes. In the latter cascade, Raf-1 inhibition dephosphorylates Bad at serine 112 and increases the levels of Bax. Fourth, we found that Raf-1 and Akt work together to promote β-cell survival and that blocking both Raf-1 and Akt signaling caused additive β-cell death. Fifth, we observed that Raf-1 plays a small but significant role in insulin secretion. Collectively, these findings establish Raf-1 as a key node in the network of β-cell survival proteins.

The conclusion that Raf-1 suppresses apoptosis in β-cells is supported by studies using a small molecule inhibitor, and also by experiments where full-length Raf-1 or dominant-negative Raf-1 mutants were overexpressed in MIN6 cells. The chemical inhibitor and both dominant-negative Raf-1 mutants significantly reduced Erk activation. The mechanisms by which the mutant proteins act as dominant negatives are likely to be overlapping but may not be identical, as suggested by their distinct subcellular distribution. Both mutants contain the Ras-binding domain, but lack the C-terminal kinase domain. Only Raf-151–220-Gfp contains the cysteine-rich domain, which may lead to differential targeting (42). Nevertheless, both dominant-negative Raf-1 mutants caused increased cell death, suggesting that their common targets (e.g. Erk) are important for β-cell survival.

Attenuation of Raf-1 kinase activity or ablation of Raf-1 protein levels is known to cause apoptosis in many cell types. The most well known function of Raf-1 kinase involves the activation of the Mek/Erk signaling. However, the generation of mice lacking the Raf-1 gene showing intact Mek/Erk activity levels enabled the identification of multiple downstream effectors other than Mek/Erk. Specifically, Raf-1 directly interacts with and phosphorylates Bad (34). In addition, deletion of the Raf-1 gene was associated with increased activity of Ask-1 (20) and mice lacking the Ask-1 gene are resistant to apoptosis induced by blocking Raf-1 signaling. Raf-1 and Ask-1 have been reported to interact directly and it has been suggested that Raf-1 catalytic activity is not required for inhibition of Ask-1-induced cell death (55). Our data were inconclusive on the role of Ask-1 in β-cells and future studies will be required. On the other hand, our data provide strong evidence for the notion that Raf-1 acts via both Erk and Bad phosphorylation in β-cells. Because Raf-1 is a central hub of numerous pro-survival signaling pathways, it is conceivable that simultaneous activation of Mek/Erk pathways and inhibition of Bad may be required to maximize β-cell survival (20).

Although ours is the first study to directly examine the consequences of blocking Raf-1 in primary and transformed β-cells, a possible role for Raf-1 in β-cell fate could be inferred from several previous studies. For example, overexpression of RKIP, a protein known to inhibit Raf-1 kinase, prevented proliferation of transformed β-cells, suggesting the possibility that Raf-1 may be involved in β-cell expansion (14). Erk, a well known downstream target of Raf-1, has also been shown to participate in pathways controlling β-cell survival. It has been reported in several studies that acute glucose and protein kinase A signaling may regulate β-cell growth and survival through Erk (17, 30, 57). On the other hand, others have shown that activation of Erk is required for human islet apoptosis in response to chronic exposure to high glucose concentrations or interleukin-1β (33). Thus, Erk signaling is activated in both pro-survival and pro-apoptotic conditions, but the outcome may depend on the timing and duration of Erk activation (58). As reported by Longuet et al. (59), Erk may also regulate insulin secretion by phosphorylating Synapsin I, a protein that is involved in insulin exocytosis (60). In the present study, we confirm that in both MIN6 cells and isolated mouse islets, blocking Raf-1 moderately reduces insulin secretion. Overall, our data further support the concept that Erk can transmit pro-survival signals and may promote insulin secretion in β-cells. However, our results with the Raf-1 inhibitor also point to the presence of important mechanisms downstream of Raf-1 that may not involve Erk.

To date, the majority of studies on β-cell survival pathways have focused primarily on the Akt kinase, its upstream regulators and downstream targets. Interestingly, transgenic mice expressing a dominant-negative/kinase-dead form of Akt under the control of the insulin promoter have normal β-cell mass and do not display increased islet cell apoptosis (12, 13). Moreover, Aikin et al. (61) reported that freshly isolated human islets have increased Akt phosphorylation despite amplified β-cell apoptosis. Thus, Akt activity alone may not be able to completely prevent β-cell death. Several other classes of pro-survival kinases are known to be important in the β-cell. For example, protein kinase A is also a critical regulator of β-cell survival. Protein kinase A acts via Erk to activate cAMP-response element-binding protein (Creb) (57, 62), which in turn controls the expression of pro-survival genes such as Bcl-2 and Insulin receptor substrate 2 (63–65). Together with the findings of others, our results demonstrate that multiple signaling kinases other than Akt are important for β-cell survival. Moreover, our data further emphasize the importance of cross-talk and interdependence of multiple kinases in the network of β-cell survival genes.

All forms of diabetes are characterized by loss of functional insulin-producing β-cells. Thus, efforts to prevent β-cell apoptosis during the pathogenesis of diabetes are necessary to ameliorate the course of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Furthermore, a reduction in β-cell apoptosis during the process of human islet culture and transplantation would likely improve graft function in transplanted islets. In the present study, we demonstrated for the first time that Raf-1 kinase is important for β-cell survival. The regulation and downstream targets of this protein warrant further investigation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Dan Luciani, Elise Kohn, Christopher McIntosh, Chris Proud, and Shernaz Bamji for helpful discussions and advice, Grace Li for assistance with mouse husbandry, Xiaoke Hu for assistance with and Dr. Michael Underhill for access to the Cellomics KineticScan instrument.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by operating grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to J. D. J.) and the Canadian Diabetes Association.

The abbreviations used are: PI, phosphatidylinositol; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase biotin-dUTP nick end labeling; Ask-1, apoptosis signaling kinase-1; Erk, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; Mek, mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorter; Gfp, green fluorescent protein; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; ER, endoplasmic reticulum.

References

- 1.Augstein P, Stephens LA, Allison J, Elefanty AG, Ekberg M, Kay TW, Harrison LC. Mol Med. 1998;4:495–501. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donath MY, Halban P. Diabetologia. 2004;47:581–589. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1336-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramachandran S, Desai NM, Goers TA, Benshoff N, Olack B, Shenoy S, Jendrisak MD, Chapman WC, Mohanakumar T. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:1696–1703. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kulkarni RN, Bruning JC, Winnay JN, Postic C, Magnuson MA, Kahn CR. Cell. 1999;96:329–339. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80546-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hashimoto N, Kido Y, Uchida T, Asahara S, Shigeyama Y, Matsuda T, Takeda A, Tsuchihashi D, Nishizawa A, Ogawa W, Fujimoto Y, Okamura H, Arden KC, Herrera PL, Noda T, Kasuga M. Nat Genet. 2006;38:589–593. doi: 10.1038/ng1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lingohr MK, Dickson LM, McCuaig JF, Hugl SR, Twardzik DR, Rhodes CJ. Diabetes. 2002;51:966–976. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.4.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohanty S, Spinas GA, Maedler K, Zuellig RA, Lehmann R, Donath MY, Trub T, Niessen M. Exp Cell Res. 2005;303:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hennige AM, Burks DJ, Ozcan U, Kulkarni RN, Ye J, Park S, Schubert M, Fisher TL, Dow MA, Leshan R, Zakaria M, Mossa-Basha M, White MF. J Clin Investig. 2003;112:1521–1532. doi: 10.1172/JCI18581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuttle RL, Gill NS, Pugh W, Lee JP, Koeberlein B, Furth EE, Polonsky KS, Naji A, Birnbaum MJ. Nat Med. 2001;7:1133–1137. doi: 10.1038/nm1001-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernal-Mizrachi E, Wen W, Stahlhut S, Welling CM, Permutt MA. J Clin Investig. 2001;108:1631–1638. doi: 10.1172/JCI13785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wrede CE, Dickson LM, Lingohr MK, Briaud I, Rhodes CJ. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49676–49684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208756200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernal-Mizrachi E, Fatrai S, Johnson JD, Ohsugi M, Otani K, Han Z, Polonsky KS, Permutt MA. J Clin Investig. 2004;114:928–936. doi: 10.1172/JCI20016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson JD, Bernal-Mizrachi E, Alejandro EU, Han Z, Kalynyak TB, Li H, Beith JL, Gross J, Warnock GL, Townsend RR, Permutt MA, Polonsky KS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19575–19580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604208103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang L, Fu Z, Binkley C, Giordano T, Burant CF, Logsdon CD, Simeone DM. Surgery. 2004;136:708–715. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trumper J, Ross D, Jahr H, Brendel MD, Goke R, Horsch D. Diabetologia. 2005;48:1534–1540. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1820-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomez E, Pritchard C, Herbert TP. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48146–48151. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209165200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Briaud I, Lingohr MK, Dickson LM, Wrede CE, Rhodes CJ. Diabetes. 2003;52:974–983. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.4.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baccarini M. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:3271–3277. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mikula M, Schreiber M, Husak Z, Kucerova L, Ruth J, Wieser R, Zatloukal K, Beug H, Wagner EF, Baccarini M. EMBO J. 2001;20:1952–1962. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.8.1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamaguchi O, Watanabe T, Nishida K, Kashiwase K, Higuchi Y, Takeda T, Hikoso S, Hirotani S, Asahi M, Taniike M, Nakai A, Tsujimoto I, Matsumura Y, Miyazaki J, Chien KR, Matsuzawa A, Sadamitsu C, Ichijo H, Baccarini M, Hori M, Otsu K. J Clin Investig. 2004;114:937–943. doi: 10.1172/JCI20317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kovacina KS, Yonezawa K, Brautigan DL, Tonks NK, Rapp UR, Roth RA. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:12115–12118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blackshear PJ, Haupt DM, App H, Rapp UR. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:12131–12134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.App H, Hazan R, Zilberstein A, Ullrich A, Schlessinger J, Rapp U. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:913–919. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.2.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koide H, Satoh T, Nakafuku M, Kaziro Y. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:8683–8686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marais R, Light Y, Paterson HF, Marshall CJ. EMBO J. 1995;14:3136–3145. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07316.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warne PH, Viciana PR, Downward J. Nature. 1993;364:352–355. doi: 10.1038/364352a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kyriakis JM, App H, Zhang XF, Banerjee P, Brautigan DL, Rapp UR, Avruch J. Nature. 1992;358:417–421. doi: 10.1038/358417a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dent P, Haser W, Haystead TA, Vincent LA, Roberts TM, Sturgill TW. Science. 1992;257:1404–1407. doi: 10.1126/science.1326789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howe LR, Leevers SJ, Gomez N, Nakielny S, Cohen P, Marshall CJ. Cell. 1992;71:335–342. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90361-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mandrup-Poulsen T. Diabetes. 2001;50(Suppl 1):S58–S63. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.2007.s58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hugl SR, White MF, Rhodes CJ. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17771–17779. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pavlovic D, Andersen NA, Mandrup-Poulsen T, Eizirik DL. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2000;11:267–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maedler K, Storling J, Sturis J, Zuellig RA, Spinas GA, Arkhammar PO, Mandrup-Poulsen T, Donath MY. Diabetes. 2004;53:1706–1713. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang HG, Rapp UR, Reed JC. Cell. 1996;87:629–638. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81383-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peruzzi F, Prisco M, Morrione A, Valentinis B, Baserga R. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:25990–25996. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103188200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jin S, Zhuo Y, Guo W, Field J. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24698–24705. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413374200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edwards LA, Verreault M, Thiessen B, Dragowska WH, Hu Y, Yeung JH, Dedhar S, Bally MB. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:645–654. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salvalaggio PR, Deng S, Ariyan CE, Millet I, Zawalich WS, Basadonna GP, Rothstein DM. Transplantation. 2002;74:877–879. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200209270-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson JD, Ahmed NT, Luciani DS, Han Z, Tran H, Fujita J, Misler S, Edlund H, Polonsky KS. J Clin Investig. 2003;111:1147–1160. doi: 10.1172/JCI16537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dror V, Nguyen V, Walia P, Kalynyak TB, Hill JA, Johnson JD. Diabetologia. 2007;50:2504–2515. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0835-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson JD, Han Z, Otani K, Ye H, Zhang Y, Wu H, Horikawa Y, Misler S, Bell GI, Polonsky KS. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:24794–24802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401216200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bondeva T, Balla A, Varnai P, Balla T. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:2323–2333. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-01-0019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang S, Ghosh RN, Chellappan SP. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:7487–7498. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lackey K, Cory M, Davis R, Frye SV, Harris PA, Hunter RN, Jung DK, McDonald OB, McNutt RW, Peel MR, Rutkowske RD, Veal JM, Wood ER. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2000;10:223–226. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00668-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zha J, Harada H, Osipov K, Jockel J, Waksman G, Korsmeyer SJ. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24101–24104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stiles BL, Kuralwalla-Martinez C, Guo W, Gregorian C, Wang Y, Tian J, Magnuson MA, Wu H. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2772–2781. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.7.2772-2781.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harding HP, Ron D. Diabetes. 2002;51(Suppl 3):S455–S461. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2007.s455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oyadomari S, Araki E, Mori M. Apoptosis. 2002;7:335–345. doi: 10.1023/a:1016175429877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oyadomari S, Koizumi A, Takeda K, Gotoh T, Akira S, Araki E, Mori M. J Clin Investig. 2002;109:525–532. doi: 10.1172/JCI14550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Srinivasan S, Ohsugi M, Liu Z, Fatrai S, Bernal-Mizrachi E, Permutt MA. Diabetes. 2005;54:968–975. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.4.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jun T, Gjoerup O, Roberts TM. Sci STKE. 1999. p. PE1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zimmermann S, Moelling K. Science. 1999;286:1741–1744. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zimmermann S, Rommel C, Ziogas A, Lovric J, Moelling K, Radziwill G. Oncogene. 1997;15:1503–1511. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hindley A, Kolch W. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:1575–1581. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.8.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen J, Fujii K, Zhang L, Roberts T, Fu H. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7783–7788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141224398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tobiume K, Saitoh M, Ichijo H. J Cell Physiol. 2002;191:95–104. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Costes S, Broca C, Bertrand G, Lajoix AD, Bataille D, Bockaert J, Dalle S. Diabetes. 2006;55:2220–2230. doi: 10.2337/db05-1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marshall CJ. Cell. 1995;80:179–185. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90401-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Longuet C, Broca C, Costes S, Hani EH, Bataille D, Dalle S. Endocrinology. 2005;146:643–654. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Matsumoto K, Ebihara K, Yamamoto H, Tabuchi H, Fukunaga K, Yasunami M, Ohkubo H, Shichiri M, Miyamoto E. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:2053–2059. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aikin R, Hanley S, Maysinger D, Lipsett M, Castellarin M, Paraskevas S, Rosenberg L. Diabetologia. 2006;49:2900–2909. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0476-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dalle S, Longuet C, Costes S, Broca C, Faruque O, Fontes G, Hani EH, Bataille D. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20345–20355. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312483200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wilson BE, Mochon E, Boxer LM. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5546–5556. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xiang H, Wang J, Boxer LM. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:8599–8606. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01062-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jhala US, Canettieri G, Screaton RA, Kulkarni RN, Krajewski S, Reed J, Walker J, Lin X, White M, Montminy M. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1575–1580. doi: 10.1101/gad.1097103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]