Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To determine if systemic corticosteroid therapy is associated with improved outcomes for children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP).

METHODS:

In this multicenter, retrospective cohort study we used data from 36 children's hospitals for children aged 1 to 18 years with CAP. Main outcome measures were length of stay (LOS), readmission, and total hospitalization cost. The primary exposure was the use of adjunct systemic corticosteroids. Multivariable regression models and propensity scores were used to adjust for confounders.

RESULTS:

The 20 703 patients whose data were included had a median age of 4 years. Adjunct corticosteroid therapy was administered to 7234 patients (35%). The median LOS was 3 days, and 245 patients (1.2%) required readmission. Systemic corticosteroid therapy was associated with shorter LOS overall (adjusted hazard ratio [HR]: 1.24 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.18–1.30]). Among children who received treatment with β-agonists, the LOS was shorter for children who had received corticosteroids compared with children who had not (adjusted HR: 1.36 [95% CI: 1.28–1.45]). Among children who did not receive β-agonists, the LOS was longer for those who received corticosteroids compared with those who did not (adjusted HR: 0.85 [95% CI: 0.75–0.96]). Corticosteroids were associated with readmission of patients who did not receive concomitant β-agonist therapy (adjusted odds ratio: 1.97 [95% CI: 1.09–3.57]).

CONCLUSIONS:

For children hospitalized with CAP, adjunct corticosteroids were associated with a shorter hospital LOS among patients who received concomitant β-agonist therapy. Among patients who did not receive this therapy, systemic corticosteroids were associated with a longer LOS and a greater odds of readmission. If β-agonist therapy is considered a proxy for wheezing, our findings suggest that among patients admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of CAP, only those with acute wheezing benefit from adjunct systemic corticosteroid therapy.

Keywords: pneumonia, bacterial pneumonia, child, therapy, epidemiology

WHAT'S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT:

Corticosteroids inhibit the expression of many proinflammatory cytokines released during the course of community-acquired pneumonia infection. Corticosteroids have been found in some studies to be associated with improved clinical outcomes in adults with pneumonia. No studies have investigated corticosteroid use in children with pneumonia.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS:

Results showed that corticosteroid treatment in children with pneumonia is common and its use is highly variable across institutions. Although corticosteroid therapy may benefit children with acute wheezing treated with β-agonists, corticosteroid therapy may lead to worse outcomes for children without wheezing.

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a common and serious infection in children.1–4 The pathophysiology of CAP is characterized by a complex inflammatory response triggered by entry of bacteria into the alveolar space. The acute phase of the host response is marked by migration of neutrophils and macrophages into infected alveoli,5,6 phagocytosis of invading pathogens, and release of proinflammatory cytokines. Subsequent recruitment and activation of T cells and B cells escalate the inflammatory response.7 The activation of this cascade benefits the host as long as it remains localized. However, excessive amplification of the inflammatory response may worsen the clinical course of pneumonia, leading to the destruction of lung parenchyma and, in more severe cases, to respiratory failure and septic shock.5,8 Considerable morbidity may occur in patients with CAP, even in the presence of appropriate antibiotic therapy.9–11

Corticosteroids inhibit the expression of many proinflammatory cytokines released during the course of CAP infection,7,12 and corticosteroid treatment may be a useful adjunct therapy in patients with CAP. Systemic corticosteroid therapy is associated with better outcomes for children with other infections, including bacterial meningitis caused by Haemophilus influenzae type B,13 and pneumonia caused by Pneumocystis jiroveci.14 Although several studies of adults with CAP have shown reductions in disease severity, hospital length of stay (LOS), and mortality in patients who received corticosteroids compared with patients who did not,15–18 the role of corticosteroids in the routine treatment of adults with CAP remains controversial.19,20 In children, available data are limited to those acquired through case series investigations and have demonstrated clinical improvement of patients with Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in temporal association with corticosteroid administration.21,22 We therefore sought to determine the association between adjunct corticosteroid therapy and outcomes for children hospitalized with CAP.

METHODS

Data Source

Data for this retrospective cohort study were obtained from the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS), which contains administrative data from 38 freestanding children's hospitals. Patient data are deidentified before inclusion in the database; however, encrypted medical record numbers allow for tracking of individual patients across hospitalizations. Data quality and reliability are assured through a joint effort by the Child Health Corporation of America (Shawnee Mission, KS) and PHIS-participating hospitals, as described previously.23,24 This study, for which we used a deidentified data set, was considered exempt from review by the committees for the protection of human subjects at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

Patients

Data for children aged 1 to 18 years with CAP were included in this study if the children were discharged from any of the 38 participating hospitals between January 1, 2006, and December 31, 2007. Data for children were eligible for inclusion in the study if the children received antibiotic therapy on the first day of hospitalization and if their illness satisfied 1 of the following International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) discharge diagnosis code criteria: (1) primary diagnosis of pneumonia (481–483.8, 485–486); (2) primary diagnosis of a pneumonia-related symptom (780.6 or 786.00–786.52 [except 786.1]) and a secondary diagnosis of pneumonia, empyema (510.0, 510.9), or pleurisy (511.0, 511.1, 511.9); or (3) primary diagnosis of empyema or pleurisy and a secondary diagnosis of pneumonia.25

Data for children younger than 1 year were excluded from the study because these children experience a high rate of viral bronchiolitis that may be difficult to distinguish from bacterial pneumonia. Data for patients with comorbid conditions that predisposed them to severe or recurrent pneumonia (eg, cystic fibrosis, malignancy, sickle cell disease) were excluded by use of a previously reported classification scheme.26 In addition, we excluded patient data from 2 hospitals because of incomplete reporting of discharge information to PHIS; thus, data from 36 hospitals were included in this study.

Study Definitions

We identified children with asthma in 2 ways: (1) asthma-related hospitalizations as identified by an ICD-9 code for asthma (493.0–493.92) in any discharge diagnosis field during any previous hospitalization in the 24 months before the current hospitalization; and (2) treatment with inhaled corticosteroids (eg, fluticasone) or leukotriene receptor antagonists on the first day of hospitalization for CAP, which suggested that these medications were a continuation of outpatient or baseline therapy. Children were considered to be acutely wheezing on admission if they were prescribed a β-agonist (ie, albuterol) on the first day of their hospitalization.

A patient was considered to have a pleural effusion at presentation if a pleural drainage procedure (eg, chest-tube placement) was performed within the first 2 days of hospitalization. Fluid boluses (normal saline, lactated Ringer's solution), vasoactive infusions (epinephrine, norepinephrine, dopamine, and dobutamine), blood-product administration (packed or washed red blood cells, fresh-frozen plasma, and coagulation factors), and invasive (endotracheal intubation) and noninvasive (continuous positive airway pressure) mechanical ventilation were used as measures of disease severity if administered on the first day of hospitalization.

Measured Outcomes

The primary outcomes of interest in this study were hospital LOS, readmission for CAP within 28 days of index discharge, and total hospital cost. Total hospital charges in the PHIS database were adjusted for hospital location by using the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid price/wage index. We used hospital-level cost-to-charge ratios to convert the charges to costs.

Measured Exposures

The main exposure was the use of adjunct systemic corticosteroids (administered either orally or intravenously), including dexamethasone, hydrocortisone, methylprednisolone, prednisolone, and prednisone.

Data Analysis

Categorical variables were described by using frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were described by using median, range, and interquartile range (IQR) values. Unadjusted analyses for LOS included median time to outcome, Kaplan-Meier curves, and the log-rank statistic. Unadjusted analyses for readmission included χ2 tests for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables.

Propensity scores were constructed by using multivariable logistic regression to estimate the likelihood of adjunct systemic corticosteroid therapy, given an observed set of baseline confounders.27–29 Variables entered into the model included age, gender, race, hospital, season of hospitalization, and hospitalization for asthma within the past 24 months. To account for clinical examination findings and severity of illness, the propensity model also included admission to an ICU within the first 2 days of hospitalization, administration of specific medications (eg, β-agonist therapy, vasoactive infusions), and performance of specific procedures (eg, mechanical ventilation, pleural-fluid drainage) and laboratory tests (eg, arterial blood gas measurements). The model c statistic was 0.84, a value that indicated that the model had good predictive capacity.27

Multivariable analysis was performed for data from the overall cohort to evaluate outcomes independently associated with adjunct systemic corticosteroid therapy, with adjustment for propensity score and for individual covariates.30,31 For LOS, modeling consisted of multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression, with censoring on death (n = 156, 0.75%), for which a hazard ratio (HR) of >1 indicated a shorter LOS. The probability of a shorter LOS was derived by using the following formula: probability of a shorter LOS = HR/(1 + HR).32 Results of a global test of proportional hazards for the propensity-adjusted regression model were not significant (P = .815). Therefore, a single model was fit for our primary analysis. For patients who were readmitted to the hospital, a multivariable logistic regression model was used. For analysis of hospital cost, the model consisted of multivariable linear regression with logarithmic transformation of the outcome to account for its skewed distribution.

To explore the possibility of important subgroup effects, we repeated the above analyses with stratification according to patient age and whether the patient received β-agonist therapy. To avoid overfitting, all models in these subanalyses were adjusted for propensity score but not for individual covariates.

Data were analyzed by using Stata 10 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). All analyses were clustered according to hospital. A 2-tailed P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Characteristics of the 20 703 patients whose data were eligible for study inclusion are shown in Tables 1 and 2. The median patient age was 4 years (IQR: 2–8 years). Overall, 2778 (13%) of the patients had been hospitalized with a diagnosis of asthma in the 24 months before the current hospitalization, and 3886 (19%) had received inhaled corticosteroids or leukotriene-receptor antagonists. Concomitant β-agonist therapy was common; 10 971 (53%) of patients received β-agonist therapy at the time of admission. The median percentage of patients who received concomitant β-agonist therapy at any hospital was 55% (range: 1%–77%; IQR: 46%–61%).

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Children With CAP, Stratified According to Whether They Received Adjunct Systemic Corticosteroids

| Overall (N = 20 703) | No Systemic Corticosteroids (n = 13 469) | Systemic Corticosteroids (n = 7234) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender, n | 10 117 (48.9) | 6613 (49.1) | 3504 (48.4) | .365 |

| Age category, n | <.001 | |||

| 1–5 y | 12 939 (62.5) | 8182 (60.8) | 4757 (65.8) | |

| 6–11 y | 4831 (23.3) | 3063 (22.7) | 1768 (24.4) | |

| 12–18 y | 2933 (14.2) | 2224 (16.5) | 709 (9.8) | |

| Race, n | <.001 | |||

| Black | 5082 (24.6) | 2868 (21.3) | 2214 (30.6) | |

| White | 12 891 (62.3) | 8832 (65.6) | 4059 (56.1) | |

| Other | 1996 (9.6) | 1347 (10.0) | 649 (9.0) | |

| Missing | 734 (3.6) | 422 (3.1) | 312 (4.3) | |

| Hospitalization characteristics, n (%) | ||||

| During viral respiratory seasona | 13 256 (64.0) | 8706 (64.6) | 4550 (62.9) | .013 |

| Previous asthma hospitalizationb | 2778 (13.4) | 1264 (9.4) | 1514 (20.9) | <.001 |

| ICU admission | 3392 (16.4) | 1994 (14.8) | 1398 (19.3) | <.001 |

Includes admission during the months of October through March.

Asthma-related ICD-9 discharge codes: 493.0–493.92.

TABLE 2.

Diagnostic Evaluations and Therapies of Children With CAP, Stratified According to Whether They Received Adjunct Systemic Corticosteroids

| Overall (N = 20 703), n (%) | No Systemic Corticosteroids (n = 13 469), n (%) | Systemic Corticosteroids (n = 7234), n (%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory tests and procedures | ||||

| Chest computed tomography or ultrasound | 778 (3.8) | 694 (5.2) | 84 (1.2) | <.001 |

| Respiratory virus tests | 3432 (20.9) | 2144 (20.4) | 1288 (21.7) | .051 |

| Arterial blood gas | 3399 (16.4) | 1972 (14.6) | 1427 (19.7) | <.001 |

| Complete blood count | 12 540 (60.6) | 8548 (63.5) | 3992 (55.2) | <.001 |

| Electrolytes | 7829 (37.8) | 5400 (40.1) | 2429 (33.6) | <.001 |

| Urine culture | 2508 (12.1) | 2034 (15.1) | 474 (6.6) | <.001 |

| Blood culture | 9580 (46.3) | 6709 (49.8) | 2871 (39.7) | <.001 |

| C-reactive protein | 4561 (22.0) | 2871 (22.3) | 1690 (23.4) | .001 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | 1010 (4.9) | 854 (6.3) | 156 (2.2) | <.001 |

| Early pleural drainage | 519 (2.5) | 480 (3.6) | 39 (0.5) | <.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 823 (4.0) | 500 (3.7) | 323 (4.5) | .008 |

| Therapies | ||||

| Chronic asthma medicationa | 3886 (18.8) | 1584 (11.8) | 2302 (31.8) | <.001 |

| β-Agonist therapy | 10 971 (53.0) | 4788 (35.6) | 6183 (85.5) | <.001 |

| Vasoactive infusions | 689 (3.3) | 313 (2.3) | 376 (5.2) | <.001 |

| Antibiotic regimen | <.001 | |||

| Aminopenicillin | 1129 (5.5) | 593 (4.4) | 536 (7.4) | |

| Macrolide | 1780 (8.6) | 626 (4.7) | 1154 (16.0) | |

| Cephalosporin | 8751 (42.3) | 5914 (43.9) | 2837 (39.2) | |

| Macrolide and cephalosporin | 3160 (15.3) | 1829 (13.6) | 1331 (18.4) | |

| Cephalosporin and vancomycin/clindamycin | 2403 (11.6) | 1949 (14.5) | 454 (6.3) | |

| Macrolide and aminopenicillin | 217 (1.1) | 86 (0.6) | 131 (1.8) | |

| Macrolide, cephalosporin, and vancomycin/clindamycin | 304 (1.5) | 223 (1.7) | 81 (1.1) | |

| Other | 2959 (14.3) | 2249 (16.7) | 710 (9.8) |

Patients were considered to be on chronic asthma therapy if they received an inhaled steroid or a leukotriene-receptor antagonist on admission.

Adjunct Corticosteroid Administration

Adjunct systemic corticosteroids were administered to 7234 (35%) of children overall. Corticosteroid administration practices varied widely among study hospitals. The median percentage of patients who received adjunct corticosteroid therapy at any hospital was 32% (range: 1%–51%; IQR: 24%–40%) (P < .001, χ2 test). Adjunct systemic corticosteroids were administered to 41% of patients who required ICU admission and to 34% of patients who did not require ICU admission (P < .001, χ2 test).

Length of Stay

Overall

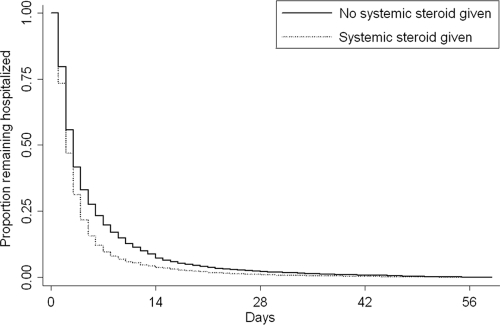

Overall, the median LOS was 3 days (IQR: 2–5 days); 17% of children had an LOS of ≥7 days and 6% of children had an LOS of ≥14 days. The LOS was ≥ 7 days for 10% of patients who received adjunct corticosteroids and for 20% of patients who did not receive them. In unadjusted analysis, systemic corticosteroid administration was associated with shorter hospital LOS (unadjusted HR: 1.26 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.20–1.32]; P < .001). The Kaplan-Meier curve that represents the proportion of patients who remained in the hospital as a function of time, stratified according to corticosteroid receipt, is shown in Fig 1.

FIGURE 1.

Kaplan-Meier curve that represents the LOS for patients who received corticosteroids and patients who did not (log-rank P < .001).

In multivariable analysis, systemic corticosteroid administration remained associated with a shorter LOS (Table 3). Both previous hospitalization for asthma (adjusted HR: 0.84 [95% CI: 0.80–0.89]; P < .001) and receipt of chronic asthma medications (adjusted HR: 0.93 [95% CI: 0.88–0.98]; P = .013) were associated with longer LOS. Receipt of β-agonist therapy was not associated with significant differences in LOS (adjusted HR: 1.04 [95% CI: 0.89–1.20]; P = .644).

TABLE 3.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Hospital LOS for Children Who Received Adjunct Systemic Corticosteroids Compared With Children Who Did Not

| Unadjusted HR (95% CI)a | Adjusted HR (95% CI)a | Pb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overallc | 1.26 (1.20–1.32) | 1.24 (1.18–1.30) | <.001 |

| Stratified according to aged | |||

| 1–5 y | 1.22 (1.16–1.28) | 1.16 (1.11–1.22) | <.001 |

| 6–11 y | 1.30 (1.22–1.38) | 1.27 (1.18–1.36) | <.001 |

| 12–18 y | 1.11 (1.02–1.20) | 1.11 (1.02–1.20) | .01 |

| Stratified according to β-agonist treatmentd | |||

| No β-agonist | 0.87 (0.76–1.01) | 0.85 (0.75–0.96) | .009 |

| β-Agonist | 1.41 (1.33–1.50) | 1.36 (1.28–1.45) | <.001 |

HR > 1 indicates a shorter hospital length of stay (ie, a greater probability of earlier discharge).

Denotes P for adjusted HR.

Overall model was also adjusted for propensity score, age, gender, race, previous asthma hospitalization, chronic asthma medication, β-agonist receipt, pleural drainage procedures, chest computed tomography or ultrasound, respiratory support, vasoactive infusions, ICU admission, arterial blood gas measurement, blood culture, and empiric antibiotic regimen.

Stratified models were adjusted only for propensity score.

Stratification according to age

Systemic corticosteroid receipt differed according to patient age (patients aged 1–5 years, 37%; aged 6–11 years, 37%; aged 12–18 years, 24%; P < .001, χ2 test). Unadjusted analysis results indicated that systemic corticosteroid therapy was associated with shorter LOS among patients in all age groups (Table 3). In propensity-adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression, corticosteroids remained associated with shorter LOS in all age groups (Table 3).

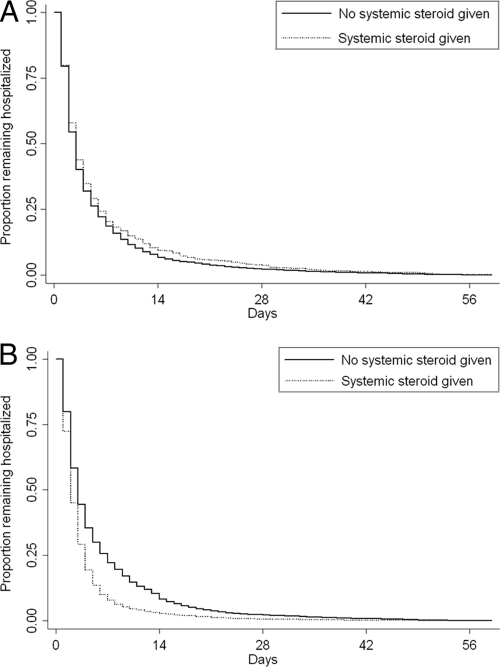

Stratification according to β-agonist therapy

Adjunct systemic corticosteroids were administered to 6183 (56.4%) of 10 971 patients who received β-agonists and 1051 (10.8%) of 9732 patients who did not receive β-agonists. In unadjusted analysis, systemic corticosteroids were associated with shorter hospital LOS among patients who received β-agonist therapy (Table 3). Kaplan-Meier curves that represent LOS according to receipt of β-agonist therapy are shown in Fig 2. The difference in LOS between patients who received corticosteroid treatment and patients who did not was statistically significant only among those patients who received β-agonist therapy (P < .001, log-rank test). In propensity-adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression, systemic corticosteroid therapy remained associated with shorter LOS among children who received β-agonist therapy (Table 3). The HR of 1.41 indicates that the odds are 1.41:1 (or the probability is 59%) that a patient who receives adjunct corticosteroid therapy will have a shorter LOS than a patient who does not receive adjunct corticosteroid therapy. In contrast, corticosteroid therapy was associated with a significantly longer LOS for patients who did not receive β-agonist therapy (Table 3).

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve that represents the LOS for patients who received corticosteroids and patients who did not among patients who did not recieve β-agonist treatment (A) (log-rank P = 0.15) and patients who did receive β-agonist treatment (B) (log-rank P < .001).

Hospital Readmission

Overall, 245 children (1.2%) were readmitted to the hospital for CAP within 28 days of index discharge. Across study hospitals, the median readmission rate was 1.3% (IQR: 0.7%–1.6%). The difference across study hospitals in the proportion of patients who required readmission was not statistically significant (P = .099, χ2 test). Readmission rates differed according to age as follows: children aged 1–5 years, 1.2%; aged 6–11 years, 0.9%; aged 12–18 years, 1.9% (P < .001, χ2 test). The readmission rate for both patients who received and those who did not receive β-agonist treatment was 1.2% (P = .62, χ2 test). In analysis of data for the overall cohort and in subanalysis of data stratified according to age, neither unadjusted nor multivariable analysis results indicated that systemic corticosteroid therapy was associated with readmission (Table 4). Subanalyses of data stratified according to β-agonist receipt indicated that corticosteroids were associated with higher odds of readmission among patients who did not receive concomitant β-agonist therapy (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Unadjusted and Adjusted 28-Day Hospital Readmission for Children Who Received Adjunct Systemic Corticosteroids Compared With Children Who Did Not

| Unadjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Pa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overallb | 0.85 (0.66–1.09) | 1.06 (0.71–1.58) | .76 |

| Stratified by agec | |||

| 1–5 y | 0.87 (0.67–1.12) | 0.93 (0.63–1.38) | .71 |

| 6–11 y | 0.63 (0.29–1.39) | 0.72 (0.21–2.46) | .601 |

| 12–18 y | 1.29 (0.68–2.48) | 1.81 (0.86–3.82) | .12 |

| Stratified according to β-agonist treatmentc | |||

| No β-agonist | 1.38 (0.75–2.55) | 1.97 (1.09–3.57) | .025 |

| β-Agonist | 0.70 (0.48–1.02) | 0.82 (0.55–1.24) | .351 |

P for adjusted odds ratio.

Overall model also was adjusted for propensity score, age, gender, race, previous asthma hospitalization, chronic asthma medication, β-agonist receipt, pleural drainage procedures, chest computed tomography or ultrasound, respiratory support, vasoactive infusions, ICU admission, arterial blood gas measurement, blood culture, and empiric antibiotic regimen.

Stratified models were adjusted only for propensity score.

Cost

Overall, the median cost for patients who were admitted to the hospital with CAP was $4719 (IQR: $2748–$10 961). Among patients who received corticosteroids, median cost was $4440, whereas among nonrecipients, it was $4941 (P < .001, Wilcoxon rank-sum test). Costs remained lower among patients who received corticosteroid treatment, according to results of subanalysis of data stratified according to age (Appendix). In subanalysis of data stratified according to β-agonist receipt, corticosteroids were associated with a higher cost among patients who did not receive β-agonists, and with a lower cost among patients who did receive β-agonists (Appendix).

DISCUSSION

In this multicenter study we examined the role of adjunct systemic corticosteroid therapy in children hospitalized with CAP. Adjunct corticosteroids were commonly used to treat children with CAP, although corticosteroid use varied considerably across participating hospitals. Corticosteroid use in CAP was not limited to patients who received concomitant β-agonist therapy. We also found that adjunct systemic corticosteroid therapy was associated with a shorter hospital LOS in the subset of patients who received concomitant β-agonist therapy. In contrast, among those patients who did not receive a β-agonist, systemic corticosteroids were associated with a longer hospital LOS and higher odds of readmission. If the administration of a β-agonist is considered as a proxy for the presence of wheezing, our findings suggest that among patients admitted with a diagnosis of CAP, only those with acute wheeze as a presenting symptom benefit from adjunct systemic corticosteroid therapy.

We found significant variation in the use of corticosteroids for CAP across hospitals. Increased illness severity and requirement for β-agonist therapy incompletely accounted for this variation. It is likely that variation in corticosteroid use across hospitals reflects poor consensus on optimal treatment of children hospitalized with CAP. Institutional culture differences may also drive variability. Randomized trials to clarify the role of adjunct corticosteroid therapy in the treatment of childhood pneumonia are necessary to determine procedures that may reduce this practice variation and optimize the care of children hospitalized with CAP.

Serum cytokines are elevated in children with CAP,33 but their expression can be inhibited by systemic corticosteroids.7 In this multicenter study of children hospitalized with CAP, we found that adjunct systemic corticosteroid therapy was associated with a shorter LOS among children who received concomitant β-agonist therapy. These effects remained even after adjustment for empiric antibiotic therapy. Our findings have important clinical implications. It is possible that the benefits of adjunct corticosteroids depend partly or exclusively on the infecting pathogen. Viruses and atypical bacterial pathogens such as M pneumoniae cause diffuse lower-airway inflammation34–36 as well as shifts in airway responsiveness.37,38 As a consequence, wheezing is common in CAP caused by viruses and atypical bacteria but uncommon in CAP caused by typical bacterial pathogens such as Streptococcus pneumoniae.39,40 The benefit of corticosteroid treatment observed among patients who received a β-agonist, a group likely to have wheezing on clinical examination, might be related to treatment of both the local inflammatory and smooth-muscle hyperreactivity components induced by infection. In contrast, mitigation of the systemic cytokine response and treatment of relative adrenal insufficiency, the proposed mechanisms of benefit in studies of adult patients,15,16,18 may be less important in children, who have lower rates of systemic complications (eg, sepsis) and death than adults with CAP.41 The timing of corticosteroid therapy relative to symptom onset, which could not be assessed in this study, may also be important, because the benefits of corticosteroids in animal models of infection were greatest in the early stages of lung inflammation.42,43

Adjunct systemic corticosteroid therapy was associated with a longer LOS and a higher odds of readmission among patients who did not receive β-agonist therapy. Corticosteroids are known to affect many aspects of the host immune response. It is possible that corticosteroid-associated impairment of the host immune response led to delayed recovery in children with bacterial pneumonia. It is also possible that systemic corticosteroids were associated with adverse effects, such as hospital-acquired infections, hypertension, and hyperglycemia, which prolonged hospitalization. Alternatively, corticosteroids may have been preferentially administered to more severely ill children (ie, confounding by indication), which caused us to underestimate the potential benefits of corticosteroids.

This study had several limitations. First, because there are no specific ICD-9 discharge diagnosis codes for CAP, it is possible that we included patients with simple asthma exacerbation rather than CAP. We minimized such misclassification by using a previously validated ICD-9 discharge diagnosis code algorithm to identify children with CAP,25 which included only children who received an antibiotic on the first day of hospitalization, and excluded patients at high risk for viral bronchiolitis (ie, those aged <1 year). We further addressed the possibility that children with wheezing had asthma rather than CAP by adjusting for previous asthma hospitalizations and by stratifying our analysis on the basis of receipt or nonreceipt of β-agonist therapy.

A second limitation was that there may have been unmeasured confounding or residual confounding by indication for adjunct corticosteroid therapy related to clinical presentation in terms of illness severity and the presence or absence of wheezing. This confounding could have influenced our results in 2 disparate ways. We expected that patients who received corticosteroid treatment would be sicker than patients who did not. We included variables associated with a greater severity of illness (such as ICU admission) in the propensity score and separately as covariates in multivariable analysis. Because we found an association between adjunct corticosteroid therapy and LOS, it is possible that the benefit of corticosteroid therapy is even greater than that found in our study. We also expected that children with previous episodes of wheezing and those with wheezing at presentation would be more likely to receive and benefit from corticosteroids. Therefore, variables associated with a history of reactive-airway disease were included in the propensity score and in the multivariable analysis. In addition, we stratified the analysis according to receipt or nonreceipt of β-agonist therapy, which should have served as a reasonable proxy for acute wheezing.

A third limitation was that we were able to record only readmissions that occurred at the same hospital as the index admission. Thus, for any patient with CAP who was readmitted and presented to a hospital not included in the PHIS database, the readmission data did not appear in our records, and the readmission was not counted. It is therefore possible that the true number of readmissions for CAP was higher than that presented here. Finally, the impact of adjunct corticosteroid therapy on other important outcomes such as progression of illness and the development of pneumonia-associated complications such as empyema could not be assessed in this study.

CONCLUSIONS

In this multicenter retrospective cohort study we found that adjunct systemic corticosteroids were associated with shorter hospital LOS overall, with particular benefit among those patients who also received concomitant β-agonist therapy. Among those patients who did not receive β-agonist therapy, systemic corticosteroids were associated with longer hospital LOS and more frequent readmissions. Our results do not support the routine use of corticosteroid treatment of children with CAP. Our findings also have important implications for the design of future clinical trials, particularly with regard to planning of sample size and study cohorts. Because the practice of prescribing adjunct corticosteroids to children with CAP is both common and highly variable, a randomized trial is warranted to allow further exploration of which pediatric populations might benefit from systemic corticosteroid therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr Weiss received support from the Infections Disease Society of American Medical Scholars Program. Drs Lee and Kronman are both recipients of a Young Investigator Award from the Academic Pediatric Association. Dr Shah received support from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant K01 AI73729) and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation under its Physician Faculty Scholar program.

APPENDIX.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Hospitalization Cost Comparison for Children Who Received Adjunct Systemic Corticosteroids Compared With Children Who Did Not

| Unadjusted β-coefficient (95% CI) | Adjusted β-coefficient (95% CI) | Pa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overallb | −0.16 (−0.25 to −0.07) | −0.11 (−0.18 to −0.05) | <.001 |

| Stratified according to agec | |||

| 1–5 y | −0.09 (−0.19 to 0.00) | −0.08 (−0.16 to −0.004) | .039 |

| 6–11 y | −0.14 (−0.23 to −0.05) | −0.16 (−0.26 to −0.05) | .004 |

| 12–18 y | −0.12 (−0.24 to 0.01) | −0.12 (−0.27 to −0.002) | .046 |

| Stratified according to β-agonist treatmentc | |||

| No β-agonist | 0.30 (0.05 to 0.54) | 0.38 (0.19 to 0.57) | <.001 |

| β-Agonist | −0.31 (−0.40 to −0.22) | −0.27 (−0.37 to −0.18) | <.001 |

P for adjusted β-coefficient.

Overall model was also adjusted for propensity score, age, gender, race, previous asthma hospitalization, chronic asthma medication, β-agonist receipt, pleural drainage procedures, chest computed tomography or ultrasound, respiratory support, vasoactive infusions, ICU admission, arterial blood gas measurement, blood culture, and empiric antibiotic regimen.

Stratified models were adjusted only for propensity score.

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

- CAP

- community-acquired pneumonia

- LOS

- length of stay

- PHIS

- Pediatric Health Information System

- ICD-9

- International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision

- IQR

- interquartile range

- HR

- hazard ratio

- CI

- confidence interval

REFERENCES

- 1. Peck AJ, Holman RC, Curns AT, et al. Lower respiratory tract infections among American Indian and Alaska Native children and the general population of U.S. Children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24(4):342–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shah SS, DiCristina CM, Bell LM, Ten Have T, Metlay JP. Primary early thoracoscopy and reduction in length of hospital stay and additional procedures among children with complicated pneumonia: results of a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(7):675–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Byington CL, Spencer LY, Johnson TA, et al. An epidemiological investigation of a sustained high rate of pediatric parapneumonic empyema: risk factors and microbiological associations. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(4):434–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grijalva CG, Nuorti JP, Arbogast PG, Martin SW, Edwards KM, Griffin MR. Decline in pneumonia admissions after routine childhood immunisation with pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in the USA: a time-series analysis. Lancet. 2007;369(9568):1179–1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mizgerd JP. Acute lower respiratory tract infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(7):716–727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Burns AR, Smith CW, Walker DC. Unique structural features that influence neutrophil emigration into the lung. Physiol Rev. 2003;83(2):309–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cazzola M, Matera MG, Pezzuto G. Inflammation: a new therapeutic target in pneumonia. Respiration. 2005;72(2):117–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sibille Y, Reynolds HY. Macrophages and polymorphonuclear neutrophils in lung defense and injury. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141(2):471–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nelson S, Bagby GJ, Bainton BG, Wilson LA, Thompson JJ, Summer WR. Compartmentalization of intraalveolar and systemic lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor and the pulmonary inflammatory response. J Infect Dis. 1989;159(2):189–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yende S, Tuomanen EI, Wunderink R, et al. Preinfection systemic inflammatory markers and risk of hospitalization due to pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(11):1440–1446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sibila O, Agusti C, Torres A. Corticosteroids in severe pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2008;32(2):259–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meduri GU, Tolley EA, Chrousos GP, Stentz F. Prolonged methylprednisolone treatment suppresses systemic inflammation in patients with unresolving acute respiratory distress syndrome: evidence for inadequate endogenous glucocorticoid secretion and inflammation-induced immune cell resistance to glucocorticoids. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(7):983–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van de Beek D, de Gans J, McIntyre P, Prasad K. Corticosteroids for acute bacterial meningitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD004405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Briel M, Bucher HC, Boscacci R, Furrer H. Adjunctive corticosteroids for Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia in patients with HIV-infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(3):CD006150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Montón C, Ewig S, Torres A, et al. Role of glucocorticoids on inflammatory response in nonimmunosuppressed patients with pneumonia: a pilot study. Eur Respir J. 1999;14(1):218–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mikami K, Suzuki M, Kitagawa H, et al. Efficacy of corticosteroids in the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization. Lung. 2007;185(5):249–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Garcia-Vidal C, Calbo E, Pascual V, Ferrer C, Quintana S, Garau J. Effects of systemic steroids in patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2007;30(5):951–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Confalonieri M, Urbino R, Potena A, et al. Hydrocortisone infusion for severe community-acquired pneumonia: a preliminary randomized study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(3):242–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Snijders D, Daniels JM, de Graaff CS, van der Werf TS, Boersma WG. Efficacy of corticosteroids in community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized double blinded clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(9):975–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Salluh JI, Povoa P, Soares M, Castro-Faria-Neto HC, Bozza FA, Bozza PT. The role of corticosteroids in severe community-acquired pneumonia: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2008;12(3):R76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee KY, Lee HS, Hong JH, et al. Role of prednisolone treatment in severe Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2006;41(3):263–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tamura A, Matsubara K, Tanaka T, Nigami H, Yura K, Fukaya T. Methylprednisolone pulse therapy for refractory Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in children. J Infect. 2008;57(3):223–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mongelluzzo J, Mohamad Z, Ten Have TR, Shah SS. Corticosteroids and mortality in children with bacterial meningitis. JAMA. 2008;299(17):2048–2055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shah SS, Hall M, Srivastava R, Subramony A, Levin JE. Intravenous immunoglobulin in children with streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(9):1369–1376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Whittle J, Fine MJ, Joyce DZ, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia: can it be defined with claims data? Am J Med Qual. 1997;12(4):187–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Feudtner C, Hays RM, Haynes G, Geyer JR, Neff JM, Koepsell TD. Deaths attributed to pediatric complex chronic conditions: national trends and implications for supportive care services. Pediatrics. 2001;107(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/107/6/e99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70(1):41–55 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stürmer T, Joshi M, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Rothman KJ, Schneeweiss S. A review of the application of propensity score methods yielded increasing use, advantages in specific settings, but not substantially different estimates compared with conventional multivariable methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(5):437–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Weitzen S, Lapane KL, Toledano AY, Hume AL, Mor V. Principles for modeling propensity scores in medical research: a systematic literature review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2004;13(12):841–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Imbens GW. Nonparametric estimation of average treatment effects under heterogeneity: a review. Rev Econ Stat. 2004;86:4–29 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Greenland S. Introduction to regression modeling. In: Rothman KJ, Greenland S. eds. Modern Epidemiology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2008:446–451 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Spruance SL, Reid JE, Grace M, Samore M. Hazard ratio in clinical trials. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(8):2787–2792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Michelow IC, Katz K, McCracken GH, Hardy RD. Systemic cytokine profile in children with community-acquired pneumonia. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2007;42(7):640–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gern JE, Martin MS, Anklam KA, et al. Relationships among specific viral pathogens, virus-induced interleukin-8, and respiratory symptoms in infancy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2002;13(6):386–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Johnston SL. Bronchial hyperresponsiveness and cytokines in virus-induced asthma exacerbations. Clin Exp Allergy. 1997;27(1):7–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Johnston SL. The role of viral and atypical bacterial pathogens in asthma pathogenesis. Pediatr Pulmonol Suppl. 1999;18:141–143 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Peebles RS, JR, Sheller JR, Johnson JE, Mitchell DB, Graham BS. Respiratory syncytial virus infection prolongs methacholine-induced airway hyperresponsiveness in ovalbumin-sensitized mice. J Med Virol. 1999;57(2):186–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Martin RJ, Chu HW, Honour JM, Harbeck RJ. Airway inflammation and bronchial hyperresponsiveness after Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in a murine model. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;24(5):577–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Michelow IC, Olsen K, Lozano J, et al. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of community-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized children. Pediatrics. 2004;113(4):701–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Biscardi S, Lorrot M, Marc E, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and asthma in children. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(10):1341–1346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(4):243–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tagliabue C, Salvatore CM, Techasaensiri C, et al. The impact of steroids given with macrolide therapy on experimental Mycoplasma pneumoniae respiratory infection. J Infect Dis. 2008;198(8):1180–1188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chu HW, Campbell JA, Rino JG, Harbeck RJ, Martin RJ. Inhaled fluticasone propionate reduces concentration of Mycoplasma pneumoniae, inflammation, and bronchial hyperresponsiveness in lungs of mice. J Infect Dis. 2004;189(6):1119–1127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]