Interplay between lysine methylation and Cdk phosphorylation in growth control by the retinoblastoma protein

This study shows that not only lysine methylation, but also modification crosstalk is common to both histone and non-histone proteins. Inducible methylation of pRb prevents its phosphorylation by cyclin-dependent kinases, thus contributing to cell cycle arrest upon genotoxic stress.

Keywords: Cdk, methylation, phosphorylation, pRb, Set7/9

Abstract

As a critical target for cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks), the retinoblastoma tumour suppressor protein (pRb) controls early cell cycle progression. We report here a new type of regulation that influences Cdk recognition and phosphorylation of substrate proteins, mediated through the targeted methylation of a critical lysine residue in the Cdk substrate recognition site. In pRb, lysine (K) 810 represents the essential and conserved basic residue (SPXK) required for cyclin/Cdk recognition and phosphorylation. Methylation of K810 by the methyltransferase Set7/9 impedes binding of Cdk and thereby prevents subsequent phosphorylation of the associated serine (S) residue, retaining pRb in the hypophosphorylated growth-suppressing state. Methylation of K810 is under DNA damage control, and methylated K810 impacts on phosphorylation at sites throughout the pRb protein. Set7/9 is required for efficient cell cycle arrest, and significantly, a mutant derivative of pRb that cannot be methylated at K810 exhibits compromised cell cycle arrest. Thus, the regulation of phosphorylation by Cdks reflects the combined interplay with methylation events, and more generally the targeted methylation of a lysine residue within a Cdk-consensus site in pRb represents an important point of control in cell cycle progression.

Introduction

Cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks) have an important function in cell cycle control, and are often deregulated in cancer (Weinberg, 1995; Dyson, 1998). pRb is an established and important tumour suppressor (Weinberg, 1995; Dyson, 1998; Stevens and La Thangue, 2003) and a well-characterized target for Cdk activity (Morgan, 1997; Malumbres and Barbacid, 2009). Growth control by pRb is influenced by Cdk phosphorylation, in which serial phosphorylation events that drive cell cycle transitions regulate pRb-dependent cell cycle progression (Kitagawa et al, 1996; Connell-Crowley et al, 1997; Mittnacht, 1998; Sherr, 2000; Ezhevsky et al, 2001; Takaki et al, 2005). The temporal regulation of pRb phosphorylation reflects the cyclical appearance of cyclin/Cdk complexes during cell cycle progression which, in turn, impacts on the ability of pRb to control key effectors of cell cycle progression such as E2F transcription factors (Mittnacht, 1998).

The pRb–E2F interaction is highly significant because the ability of pRb to bind to E2F coincides with growth inhibition and cell cycle delay (Dyson, 1998; Stevens and La Thangue, 2003). The Rb gene is mutated in some human tumours, and functionally inactivated usually through increased Cdk activity in the majority of other tumours that harbour wild-type pRb (Stevens and La Thangue, 2003). Both mutation in the gene and functional inactivation prevent pRb from binding to E2F, leaving E2F in an active state (Dyson, 1998; Stevens and La Thangue, 2003). The interaction between pRb and E2F results in reduced transcription of target genes and, reflecting the physiological context in which this occurs, might involve different mechanisms. For example, pRb binds to the E2F-1 transcriptional activation domain, and masking of the activation domain provides one level for downregulating E2F-dependent transcription (Dyson, 1998; Blais and Dynlacht, 2007). pRb can mediate active repression by recruiting proteins that modulate chromatin, including histone deacetylase, histone methyltransferases (MTase) and chromatin remodelling proteins (Blais and Dynlacht, 2007; van den Heuvel and Dyson, 2008). This enables pRb to influence the chromatin environment of target genes, by deacetylating and methylating histone tails, facilitating binding of proteins like HP1 that enable transcriptional silencing (van den Heuvel and Dyson, 2008).

In normal cycling cells, pRb is principally under the control of Cdk activity, which phosphorylates pRb in a sequential and temporally regulated manner (Morgan, 1997). Several other post-translational mechanisms impinge on pRb. For example, pRb is acetylated by different acetyltransferases (p300 and P/CAF), and acetylation of pRb is regulated under conditions of cell cycle exit, such as differentiation and DNA damage (Chan et al, 2001; Nguyen et al, 2004; Markham et al, 2006). Further, pRb can be directly methylated on lysine residues by the Set7/9 methyltransferase, which, by creating a binding site for HP1, provides another mechanism that contributes to pRb transcriptional repression (Munro et al, 2010).

Methylation on lysine residues controls protein activity. This is particularly clear in the context of chromatin biology, where lysine methylation in core histones has a striking effect on gene activity (Martin and Zhang, 2005). The type of methylation event (mono-, di- or tri-), together with its interplay with other types of post-translational modification (Nishioka et al, 2002; Fischle et al, 2005; Latham and Dent, 2007), provides a sophisticated level of crosstalk in which lysine methylation provides an important underpinning role (Latham and Dent, 2007).

We reasoned that the interplay between post-translational modifications might be a general phenomenon, which is relevant to pathways that impact on fundamental cellular processes. To this end, we considered the possibility that cell cycle control through Cdk-dependent phosphorylation is integrated with different levels of post-translational modification. We report here that the pivotal Cdk target pRb is regulated through the interplay between phosphorylation and methylation. Significantly, pRb methylation at lysine (K)810 hinders subsequent Cdk phosphorylation throughout pRb to augment growth inhibition. Our results define a new level of control imposed on pRb, and more generally highlight the interplay between methylation and phosphorylation in regulating cell cycle progression.

Results

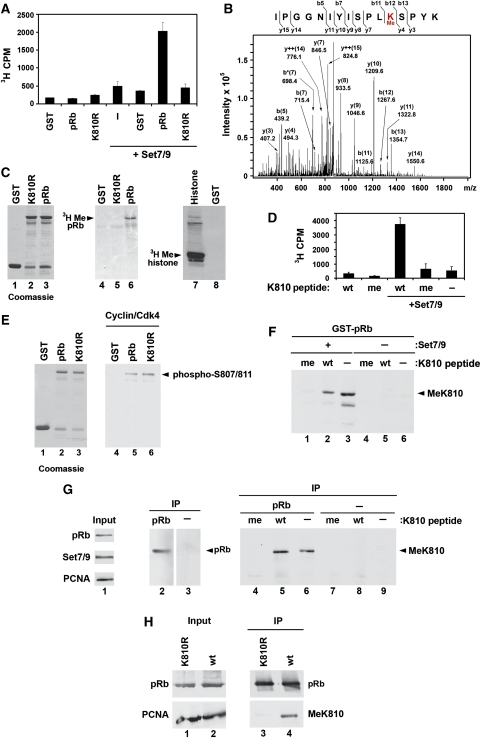

pRb is methylated at K810

pRb could be methylated by the methyltransferase Set7/9 (Figure 1A) and by mass spectrometry, we identified residue K810 in the C-terminal region of pRb as a site of methylation (Figure 1A and B). To examine the role of K810 methylation in greater detail, wild-type GST-pRb or a lysine to arginine substitution mutant (K810R) was used as a substrate for in vitro methylation. GST-pRb was efficiently methylated, contrasting with GST-pRb K810R (Figure 1A and C). Further, a pRb peptide that spans K810 was efficiently methylated by Set7/9, whereas a peptide chemically methylated on K810 was not (Figure 1D). Together, these results suggest that K810 is a site of methylation.

Figure 1.

pRb is mono-methylated by Set7/9 in vitro and in cells at lysine 810. (A) GST, GST-pRb or GST-pRb K810R (1 μg) was methylated in vitro in the presence or absence of recombinant Set7/9 (0.5 μg). After 1 h, incorporation of radio-labelled methyl groups was monitored by filter assay and scintillation counting. (B) Mass spectrometric profile of human pRb covering residues 799–814. Analysis by LC–MS/MS revealed the presence of mono-methylated lysine 810. The MS/MS spectrum of the modified tryptic peptide IPGGNIYISPLKMeSPYK [M+2H]2+ 881.1 Da (MW 1760.0 Da) is shown. Fragment ions are indicated as b and y ions. ++ represents a charge state of 2 and * represents loss of NH3. (C) GST, GST-pRb or GST-pRb K810R (1 μg) was methylated in vitro with recombinant Set7/9 (0.5 μg). After 1 h, samples were separated by SDS–PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose to permit autoradiography. The position of radio-labelled pRb and histones are marked. The coomassie blue stained gel is included as a loading control. (D) A 15 amino-acid peptide (wt—ISPLKSPYKISEGLC), containing the K810 methylation site of pRb, was used as a substrate for an in vitro methylation assay in the presence or absence of recombinant Set7/9 (0.5 μg). A peptide containing a chemically modified mono-methylated lysine at position 810 was also included as a control (me—ISPL[KMe]SPYKISEGLC). After 1 h, incorporation of radio-labelled methyl groups was monitored by filter assay and scintillation counting. (E) GST, GST-pRb or GST-pRb K810R (1 μg) was phosphorylated in vitro with recombinant cyclin D1/Cdk4 (150 ng). After 1 h, samples were separated by SDS–PAGE and analysed by immunoblotting with an anti-phospho-pRb (S807/S811) antibody. The coomassie blue stained gel is included as a loading control. The position of phospho-pRb is marked. (F) GST-pRb (1 μg) was methylated in vitro in the presence or absence of recombinant Set7/9 (0.5 μg). The reaction was halted and analysed by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting with the anti-MeK810 antibody, in the presence of 10 μg/ml competing wild-type (wt) or mono-methylated K810 peptide (me). Methylated recombinant pRb is indicated. (G) Cell extracts from U2OS cells transfected with HA-pRb (7 μg) and myc-Set7/9 (3 μg) were used in an immunoprecipitation with anti-HA (IP pRb) or non-specific antibodies (IP–). Immunoprecipitated protein was analysed by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody (lanes 2 and 3) or anti-MeK810 antibody (lanes 4–9), in the presence of 10 μg/ml competing wild-type (wt) or mono-methylated K810 peptide (me). Immunoprecipitated pRb and methylated pRb are indicated. (H) Cell extracts from U2OS cells transfected with HA-pRb (wt) or HA-pRb K810R (7 μg) were used in an immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibody (IP). Immunoprecipitated protein was analysed by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody (pRb) or anti-MeK810 antibody as indicated.

To exclude the possibility that the K810R mutant was generally inactive as an enzyme substrate, GST-pRb K810R was phosphorylated in vitro by recombinant cyclin D1/Cdk4, which is one of the Cdks that is responsible for pRb phosphorylation during cell cycle progression (Kitagawa et al, 1996; Takaki et al, 2005). The level of phosphorylation was comparable to GST-pRb (Figure 1E). Therefore, while defective for methylation, K810R still acts as an efficient substrate for Cdk phosphorylation.

To address whether methylation of pRb occurred in cells, we prepared a modification-specific antibody, anti-MeK810, against the methylated pRb peptide. Anti-MeK810 recognized the methylated pRb peptide but not the unmethylated peptide (Supplementary Figure S1A). The antibody detected methylated GST-pRb after treatment with Set7/9, with minimal reactivity against untreated GST-pRb (Figure 1F). Further, the unmodified pRb peptide competed poorly with the anti-MeK810 antibody binding to methylated GST-pRb, whereas the methylated peptide prevented binding of the anti-MeK810 antibody (Figure 1F).

In cells, when pRb and Set7/9 were co-expressed and immunoprecipitated, anti-MeK810 recognized pRb (Figure 1G). Once more, binding of anti-MeK810 was competed poorly by the unmodified pRb peptide, yet efficiently by the methylated pRb peptide (Figure 1G). A similar immunoprecipitation experiment from transfected cells was performed using the pRb derivative K810R. Unlike wild-type pRb, the K810R mutant displayed reduced levels of methylation (Figure 1H). In sum, these results suggest that pRb methylation at K810 occurs in cells.

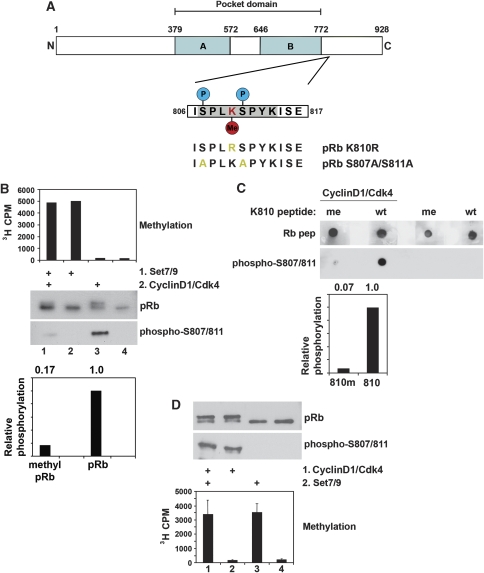

K810 resides within a Cdk-phosphorylation site

The K810 residue lies within a region phosphorylated by Cdk kinase, where K810 provides the conserved and essential basic residue (SPXK) and is flanked by serine residues S807 and S811 (Figure 2A). We reasoned therefore that methylation of K810 might influence Cdk-dependent phosphorylation of the surrounding serine residues. To test this idea, a sequential in vitro methylation and phosphorylation reaction was performed, where the effect of a prior methylation event on subsequent pRb phosphorylation was examined (Figure 2B). Methylation of pRb had a dramatic effect on subsequent Cdk phosphorylation, reducing it by ∼80% (Figure 2B). A similar effect was apparent when the methylated and unmodified pRb peptides were subjected to Cdk phosphorylation, as the wild-type pRb peptide was efficiently phosphorylated while the mono-methylated peptide was not (Figure 2C). When the experiment was performed in the reverse order, the level of pRb methylation was not affected by a pre-treatment Cdk phosphorylation step (Figure 2D), indicating that the impact of methylation on phosphorylation is directional and enforced on the hypophosphorylated form of pRb. Methylation at K810 is therefore linked to reduced levels of Cdk phosphorylation.

Figure 2.

pRb methylation by Set7/9 antagonizes phosphorylation. (A) Diagram of pRb depicting the pocket domain of the protein and the C-terminal domain containing the K810 methylation site (seen in red). The flanking serine residues that are targeted for phosphorylation by cyclin/Cdk complexes are also indicated (seen in blue). The Cdk-consensus site in this region of pRb is highlighted in grey. The sequences of the two mutant pRb proteins generated for this study (pRb K810R and pRb S807A/S811A) are also displayed, with the altered residues highlighted in yellow. (B) GST-pRb (0.5 μg) was methylated in vitro by Set7/9 (0.5 μg) for 3 h. A filter assay was performed to demonstrate that methylation of pRb had occurred (top graph). Recombinant cyclin D1/Cdk4 (150 ng) was then added to the indicated reactions in the presence of 200 μM ATP for 30 min. The reaction was subsequently halted and separated by SDS–PAGE. Immunoblotting was then performed using an anti-pRb antibody or phospho-specific pRb antibodies to neighbouring phosphorylation sites (S807/S811). The signal for pRb phosphorylation was quantified and standardized to the input pRb signal before being expressed as relative levels in the graph underneath. (C) A 15 residue peptide spanning the proposed K810 methylation site (wt) (25 μg) was combined in an in vitro phosphorylation assay with recombinant cyclin D1/Cdk4 (150 ng) and 200 μM ATP. A similar peptide containing a chemically modified mono-methylated lysine 810 was also used (me). After 1 h, reactions were spotted onto nitrocellulose and immunoblotting was performed using an anti-pRb peptide antibody (Rb pep) or a phospho-specific pRb antibody that recognizes phosphorylation at sites present in the peptide (S807/S811). The signal for pRb phosphorylation was quantified and standardized to the input peptide signal before being expressed as relative levels in the graph underneath. (D) GST-pRb (0.5 μg) was phosphorylated in vitro by cyclin D1/Cdk4 (150 ng) for 1 h. Immunoblotting with anti-pRb or anti-phospho-pRb (S807/S811) antibodies was performed to confirm phosphorylation had occurred. Recombinant Set7/9 (0.5 μg) was then added to the indicated reactions for further 30 min. The reaction was spotted onto filters and incorporation of radio-labelled methyl groups was monitored by scintillation counting.

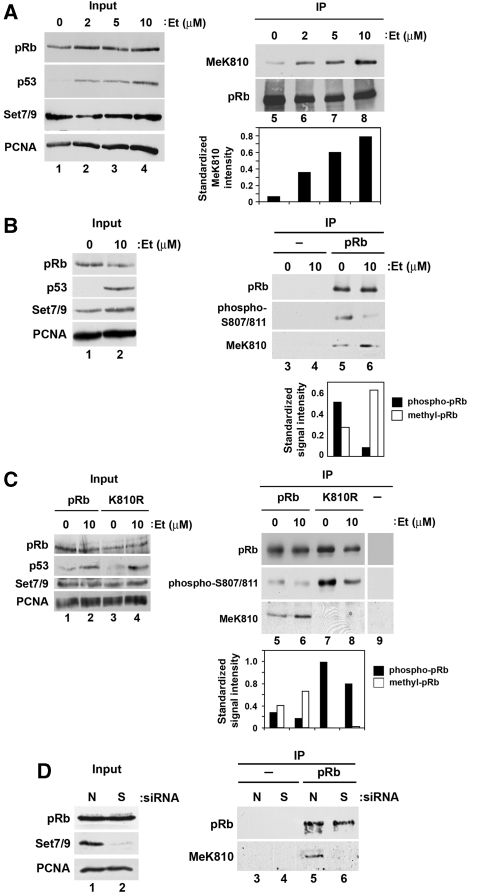

The regulation of pRb during the DNA damage response contributes to cell cycle arrest (Knudsen et al, 2000); Cdk-dependent phosphorylation is reduced, and pRb remains in the hypophosphorylated state (Knudsen et al, 2000). We considered it possible therefore that, under conditions of DNA damage, pRb methylation might be regulated. We tested this idea by co-expressing pRb and Set7/9 in U2OS cells treated with etoposide. Increased methylation was apparent in DNA damaged cells and the level of K810 methylation increased in proportion with the dose of etoposide (Figure 3A). Subsequently, we examined the phosphorylation level of methylated pRb in DNA damaged cells. The increased levels of K810 methylation coincided with reduced phosphorylation, which contrasted with untreated cells where pRb displayed high phosphorylation and low methylation levels (Figure 3B). To confirm the importance of K810 methylation in the DNA damage response, the properties of K810R were investigated (Figure 3C). Although there was a decrease in phosphorylation of K810R after etoposide treatment, the constitutive level of phosphorylation was much greater than observed for wild-type pRb and, as expected, K810 methylation was not apparent, in contrast to wild-type pRb (Figure 3C). The cell-based results therefore recapitulate the biochemical antagonism between pRb methylation and phosphorylation.

Figure 3.

pRb methylation is DNA damage responsive. (A) U2OS cells were transfected with expression vectors encoding HA-pRb (7 μg) and myc-Set7/9 (3 μg) for 24 h. Cells were then treated with the indicated amount of etoposide for further 16 h. pRb was immunoprecipitated from cells using anti-HA antibody (IP) and analysed by immunoblotting with anti-HA (pRb) or anti-MeK810 antibody. The MeK810 signal was quantified and standardized to the immunoprecipitated pRb signal in each lane to generate the graph below. (B) U2OS cells were transfected as described above. Cells were then treated with the indicated amount of etoposide for further 16 h. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated using anti-HA (IP pRb) or non-specific (IP–) antibodies. Immunoprecipitated pRb was probed with anti-HA (pRb), anti-phospho-pRb S807/S811 or anti-MeK810 antibody. The MeK810 and phospho-pRb signals were quantified and standardized to the immunoprecipitated pRb signal in each lane to generate the graph below. (C) U2OS cells were transfected as described above with HA-pRb or HA-pRb K810R. Cells were then treated with the indicated amount of etoposide for further 16 h. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA (IP pRb and K810R) or non-specific (IP–) antibody. Immunoprecipitated pRb was immunoblotted with anti-HA (pRb), anti-phospho-pRb S807/S811 or anti-MeK810 antibody. The MeK810 and phospho-pRb signals were quantified and standardized to the immunoprecipitated pRb signal in each lane to generate the graph below. (D) U2OS cells were transfected with 20 nM Set7/9 (S) or non-targeting siRNA (N) for 72 h. Endogenous pRb was then immunoprecipitated from the cell extracts using anti-pRb (IP pRb) or non-specific (IP–) antibody. The resulting immunoprecipitate was then immunoblotted with anti-pRb or anti-MeK810 antibody.

We assessed whether the results obtained with ectopic pRb reflected the control of endogenous pRb. When pRb was immunoprecipitated from U2OS cells, methylation at K810 was apparent (Figure 3D). Moreover, K810 methylation was dependent upon Set7/9 because methylation at K810 was no longer apparent upon Set7/9 depletion (Figure 3D); similar results were obtained in other cell types including HeLa cells (Supplementary Figure S1B). Thus, endogenous pRb methylation at K810 is mediated by Set7/9.

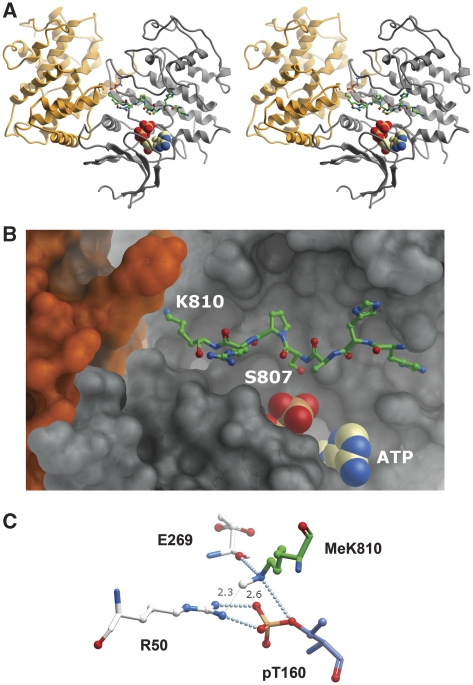

Structural implications of K810 methylation

It was of interest to consider the structural implications of pRb methylation at K810 that might help explain the observed antagonism between methylation and phosphorylation. The high-resolution crystal structure of cyclinA/Cdk2 in complex with a Cdk substrate peptide (Figure 4A) containing the SPXK-consensus site (Brown et al, 1999) provided an explanation for the reduced Cdk phosphorylation upon K810 methylation. In the substrate peptide–cyclin/Cdk complex, the lysine side chain in the consensus site, which is critical for kinase activity, is oriented towards a cleft formed at the interface of the cyclin/Cdk2 complex (Figure 4A and B). The Nɛ atom of the K residue in the substrate peptide makes, besides the charge interaction found between the positively charged Nɛ and the phosphate of phosphorylated T160 in Cdk2, essential hydrogen bond contacts towards the phosphate group of the phosphorylated T160 residue in the activation loop, and the main-chain carbonyl of E269 in the cyclin protein (Figure 4C). While methylation of the Nɛ of K810 would not necessarily result in diminished ability to form the critical salt bridges or hydrogen bonds, it is likely that lysyl methylation results in steric clashes with the cyclin/Cdk interface formed between R50 and phosphorylated T160 in Cdk2, to dislodge the K810 side chain out of its binding pocket (Figure 4C). This would lead to lower binding efficiency of the cyclin/Cdk complex to the substrate peptide and consequently reduced levels of Cdk-dependent phosphorylation.

Figure 4.

Influence of methylation on binding of a SPXK-consensus substrate peptide to the Cdk complex. (A) Stereo overview of the cyclin/Cdk2/ATP/consensus peptide complex (PDB id 1 qmz). The cyclin (orange), Cdk2 (grey) molecules are shown as ribbon diagrams, the substrate peptide (green) as ball and stick and ATP as a space-filling model. (B) The side chain of K810 of the substrate peptide (green) protrudes into a cleft formed between cyclin (orange surface) and Cdk2 (grey surface). These interactions are essential for the subsequent phosphorylation of S807 through ATP hydrolysis. (C) Model of mono-methylated K810 of the Rb substrate peptide at the cyclin/Cdk2-active site. Methylation of the Nɛ group of K810 results in steric incompatibilities (atomic distances to nh1 of R50 and to o3p of pT160 are highlighted) at the cyclin/Cdk2 interface if the essential hydrogen bond contacts (light blue spheres) are constrained. Methylation of K810 destabilizes the essential K810 contacts to the cyclin/Cdk2 interface and results in diminished binding of the substrate peptide S807 residue to the Cdk-active site.

K810 methylation impacts on E2F target genes

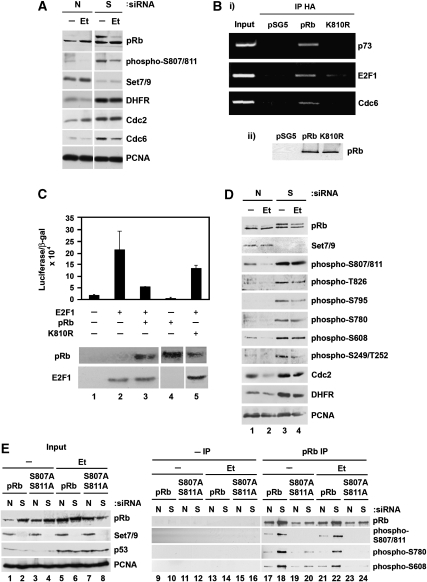

The E2F family of transcription factors is controlled through pRb and related proteins, where hypophosphorylated pRb binds to E2F thereby physically hindering transcriptional activation (Weinberg, 1995; Dyson, 1998). We considered that the enhanced pRb methylation under DNA damage conditions might be relevant to the regulation of E2F target genes, and therefore compared the expression of a number of E2F target genes, including Cdc2, Cdc6, DHFR and E2F-1 (Stevens and La Thangue, 2003) in Set7/9 depleted to control-treated cells. As expected, decreased levels of Set7/9 coincided with increased levels of pRb phosphorylation (Figure 5A; Supplementary Figure S1C). Under conditions of Set7/9 depletion, there was an increase in DHFR, Cdc2, Cdc6 and E2F-1 expression (Figure 5A and D; Supplementary Figure S1C and D). The modest reduction of pRb phosphorylation at S807/811 that occurred under DNA damage conditions with Set7/9 depletion might reflect the induction of cyclin/Cdk inhibitors, such as p21 (el-Deiry et al, 1994). Further, when ectopic wild-type pRb was expressed, the expression level of different E2F target genes (DHFR and Cdc2) was reduced, and reactivated upon Set7/9 depletion (Supplementary Figure S1E). In contrast, K810R had a minimal effect on E2F gene expression and was not affected by Set7/9 siRNA (Supplementary Figure S1E). The reduced effect of K810R to wild-type pRb reflected increased levels of K810R phosphorylation (Figure 3C) and, by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), lower binding of K810R compared with wild-type pRb to E2F sites in target genes (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Consequences of pRb methylation on cell cycle regulation. (A) U2OS cells were transfected with 20 nM Set7/9 (S) or non-targeting (N) siRNA for 72 h. Cells were also treated with 10 μM etoposide (Et) for the last 16 h where appropriate. Cell extracts were then prepared and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (B) (i) SAOS2 cells were transfected with empty vector (pSG5), HA-pRb or HA-pRb K810R (4 μg) as indicated. After 48 h, cells were cross-linked in formaldehyde and chromatin immunoprecipitation samples were prepared. Immunoprecipitation was performed using anti-HA antibody and analysed by PCR. (ii) Input levels of transfected HA-pRb and HA-pRb K810R were detected by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody (pRb). (C) SAOS2 cells were transfected with HA-pRb or HA-pRb K810R (2 μg), together with HA-E2F-1 (300 ng), the pCycE-luc reporter plasmid (300 ng) and pCMV-βgal (300 ng) as the internal control. The relative reporter activity (luciferase/β-galactosidase) is indicated with standard deviation as shown. Lower panel shows the levels of pRb and E2F-1 detected by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody. (D) U2OS cells were transfected with 20 nM Set7/9 (S) or non-targeting (N) siRNA for 72 h. Cells were also treated with 10 μM etoposide (Et) for the last 16 h where appropriate. Cell extracts were then prepared and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (E) U2OS cells were transfected with 20 nM Set7/9 (S) or non-targeting (N) siRNA. After 24 h, cells were transfected with expression vectors for HA-pRb or HA-pRb S807A/S811A (4 μg) and left for further 48 h. Cells were also treated with 10 μM etoposide (Et) for the last 16 h where appropriate. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA (pRb IP) or non-specific (–IP) antibody. Immunoprecipitated pRb was immunoblotted with anti-HA (pRb), anti-phospho-S807/811, anti-phospho-S780 or anti-phospho-S608 antibody where indicated. Quantitation of the results is presented in Supplementary Figure S1F.

Most significantly, Set7/9 influenced phosphorylation throughout pRb because, in conditions of Set7/9 depletion, a variety of other Cdk consensus sites showed enhanced levels of phosphorylation (notably T826, S608, S780, S795, S249 and T252; Figure 5D). To assess the importance of K810 methylation and S807/811 hypophosphorylation in regulating the overall level of pRb phosphorylation, we evaluated the phosphorylation status of another mutant, S807A/S811A, in which S807 and S811 had been altered to non-phosphorylatable alanine (A) residues, thus recapitulating the effect of methylation at K810 and the consequent hypophosphorylation at S807 and S811 (Figure 2B). The S807A/S811A mutant exhibited reduced phosphorylation at Cdk sites throughout pRb (Figure 5E). For example, phosphorylation at S780 and S608 was reduced compared with wild-type pRb, and Set7/9 depletion caused enhanced phosphorylation throughout wild-type pRb, this being particularly clear under DNA damage conditions, with minimal effect on S807A/S811A (Figure 5E, compare track 22 with 24; Supplementary Figure S1F). These results suggest that the ability of Set7/9 to methylate pRb at K810, and thereby hinder phosphorylation at S807/811, subsequently impacts on phosphorylation at Cdk sites throughout pRb.

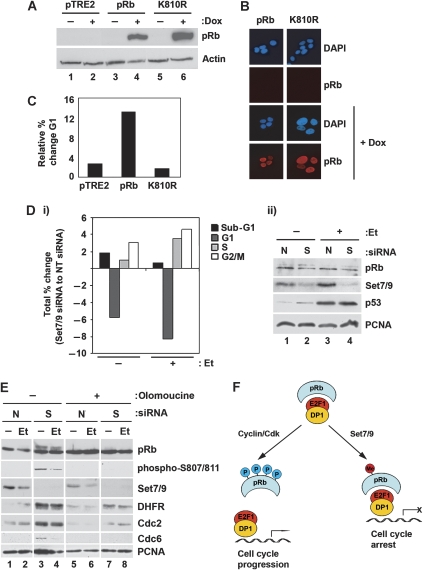

In order to examine the functional consequence of pRb methylation in cell cycle control, we studied the properties of stable cell lines in which the expression of wild-type pRb or K810R was under conditional control (using the Tet-On system). In conditions where both wild-type pRb and K810R were at a similar level of expression and location (Figure 6A and B), wild-type pRb caused a greater increase in the size of the G1 population compared with K810R, where the G1 population remained similar to the control parental cell line (Figure 6C). This result suggests that the integrity of K810 is required for efficient cell cycle arrest. This interpretation is compatible with the effect of Set7/9 depletion, which caused a reduction in the size of the G1 population (Figure 6D). Overall, therefore, K810 and Set7/9 methylation are implicated in cell cycle arrest.

Figure 6.

Cell cycle effects of methylated pRb. (A) U2OS cells stably expressing inducible wild-type pRb, pRb K810R or pTRE2 (empty vector control) were treated with 1 μg/ml doxycycline (Dox) for 72 h to induce expression. Induced pRb was detected using anti-Flag antibody. (B) Inducible wild-type pRb and pRb K810R U2OS cells were plated onto glass coverslips and treated as in (A). Induced pRb was detected using anti-Flag antibody and DAPI was used to visualize nuclei. (C) U2OS cells stably expressing inducible wild-type pRb, pRb K810R or pTRE2 (empty vector control) were treated with 1 μg/ml doxycycline for 72 h to induce expression. Cells were then prepared for cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry as detailed in Materials and methods. The mean percentage of cells observed in G1 was then derived from triplicate samples for each condition. The data were expressed in graphical format as the relative difference between the mean percentage of G1 cells before and after induction with doxycycline. (D) U2OS cells were transfected with 20 nM non-targeting (N) or Set7/9 (S) siRNA for 72 h. Cells were also treated with 10 μM etoposide for 16 h (Et) where indicated. Cells were then prepared for cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry as detailed in Materials and methods. The mean percentage of cells in each stage of the cell cycle was then derived from triplicate samples. The data were expressed in graphical format as the difference between the mean percentages of cells treated with Set7/9 siRNA or non-targeting siRNA (under the presence and absence of etoposide (Et)) (i). Actual G1 values were as follows: no etoposide treatment, non-targeting siRNA=67.16±1.20%, Set7/9 siRNA=61.38±0.48% (P<0.01); with etoposide treatment, non-targeting siRNA=56.74±0.61%, Set7/9 siRNA=48.46±0.23% (P<0.01). The corresponding immunoblot for this analysis is also shown (ii). (E) U2OS cells were transfected with 20 nM non-targeting (N) or Set7/9 (S) siRNA for 72 h. Cells were also treated with 10 μM etoposide (Et) and 300 μM olomoucine for 16 h where indicated. Cell extracts were prepared and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (F) Model depicting the effect of methylation on Cdk-dependent growth control. Cdk phosphorylation of pRb relieves cell cycle arrest by facilitating the expression of E2F target genes. Under conditions of methylation, pRb remains in a hypophosphorylated growth-arresting state, thereby limiting E2F target gene expression assisting cell cycle arrest.

Finally, to clarify the importance of functional Cdk activity in the effect of Set7/9 depletion, we treated cells with the Cdk inhibitor olomoucine (Raynaud et al, 2005). Under conditions of Set7/9 depletion and olomoucine treatment, pRb phosphorylation was not apparent and a reduced expression of E2F target genes, including DHFR, Cdc2 and Cdc6, was observed (Figure 6E). These results confirm that Set7/9 antagonizes Cdk-dependent cell cycle progression.

Discussion

Interplay between methylation and phosphorylation in pRb control

Our results suggest that a type of post-translational code governs Cdk-dependent growth control, a conclusion which has been exemplified through studying the critical Cdk target pRb. Specifically, an influential Cdk-consensus phosphorylation site in pRb is modified by methylation on lysine K810, which impedes subsequent recognition and phosphorylation by Cdks. This methylation event is sufficient to hold pRb in the hypophosphorylated state by limiting Cdk phosphorylation throughout the entire pRb protein, at Cdk sites distal to K810, thereby preventing E2F target gene expression and halting cell cycle progression (Figure 6F). At a structural level, methylation of the lysine residue interferes with Cdk recognition by virtue of impeding the tight fit between the lysyl side chain and the binding pocket in the cyclin/Cdk complex.

The physiological regulation of K810 methylation occurred in situations where Cdk-dependent phosphorylation of pRb is known to be reduced. For example, during the DNA damage response, pRb is instrumental in mediating cell cycle arrest (Knudsen et al, 2000). Under these conditions, the level of pRb methylation increased, which coincided with low levels of pRb phosphorylation. It is well established that one level of control that impacts on Cdk activity is through the induction of Cdk inhibitors, like the p53 responsive gene encoding p21/Waf1 (Vidal and Koff, 2000). Our results establish, however, that lysine modification of Cdk substrates within the consensus Cdk phosphorylation site provides an alternative and direct substrate-based mechanism that also has a major impact on Cdk activity. Such a mechanism could have widespread significance in modulating the consequences of Cdk activity on cell cycle substrates like pRb.

pRb is subject to a variety of post-translational modifications, including phosphorylation, ubiquitination, acetylation and methylation (Mittnacht, 1998; Chan et al, 2001; Uchida et al, 2005; Munro et al, 2010), and interacts with a large number of nuclear proteins involved with transcription and chromatin control (Macaluso et al, 2006). pRb regulates different cell fates, including cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, differentiation and senescence (Classon and Harlow, 2002; Giacinti and Giordano, 2006; van den Heuvel and Dyson, 2008). Our results imply that methylation at K810 through its ability to impact on Cdk phosphorylation regulates the biological activity of pRb. It is possible that pRb methylation cooperates with the induction of p21, and that both mechanisms act together as a fail safe mechanism in limiting pRb phosphorylation by Cdks.

The results described here have documented an additional site of lysine methylation, and described its interplay with pRb phosphorylation, where methylation of K810 subsequently impedes Cdk phosphorylation. This is a striking example of interplay between two different types of modification, where one event (lysine methylation) is mutually antagonistic with another event (phosphorylation), which results in opposing outcomes on pRb activity (namely active or inactive growth suppression, respectively). Moreover, as the DNA damage response is principally a protective mechanism that allows cells to survive under adverse conditions, it is possible that a pRb demethylation event occurs that subsequently allows re-entry into the cell cycle. It will be interesting to assess whether pRb is regulated by a demethylation event, and the functional consequences on cell cycle progression.

In addition to providing a new mechanism for modulating Cdk kinase activity, our study implicates Set7/9 with a key co-ordinating role in cell cycle control, as Set7/9 also targets the p53 tumour suppressor protein (Chuikov et al, 2004). As pRb and p53 take on central roles in controlling cellular proliferation, methylation may provide an important signal that integrates these two crucial pathways.

Materials and methods

Plasmids

pGEX-pRb (379–928) (Bandara et al, 1991), pGEX-Set7/9 (52–366) (Wilson et al, 2002), pGEX-Set7/9 (1–366) (Wilson et al, 2002), pSG5-HA-pRb (Markham et al, 2006), pcDNA-HA-E2F-1 (Zalmas et al, 2008), pCMV-βgal (Zalmas et al, 2008) and pCycE-luc (Botz et al, 1996) have been described previously. pcDNA-myc/his-Set7/9 was created by subcloning Set7/9 into pcDNA3.1/myc-His A (Invitrogen). pGEX-pRb-K810R, pSG5-HA-pRb-K810R and pSG5-HA-pRb-S807A/S811A were generated by site-directed mutagenesis using a QuickChange kit (Stratagene) from pGEX-pRb and pSG5-HA-pRb, respectively. pTRE2hyg-pRb and pTRE2hyg-pRb-K810R were generated by subcloning pRb (379–928) or pRb-K810R (379–928) into pTRE2hyg (Clontech). pGEX-4T1 was supplied by GE Life Sciences.

Tissue culture and transfections

U2OS, HeLa or SAOS2 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin. Transfections with the indicated plasmids were performed in 10 or 15 cm dishes using GeneJuice (Novagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were left 48 h before harvesting. RNA interference was performed using 20 nM (for U2OS cells) or 50 nM (for HeLa cells) Set7/9 siRNA (Ambion, siRNA sequence: 5′-AGAUAACAUUCGUCAUGGA-3′) or non-targeting siRNA (Dharmacon) for 72 h in oligofectamine (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation

The following antibodies were used in immunoblots: anti-pRb polyclonal (C15), anti-pRb monoclonal (IF8), anti-p53 monoclonal (DO1), anti-E2F-1 monoclonal (KH95), anti-myc monoclonal (9E10), anti-PCNA monoclonal (PC10), anti-DHFR polyclonal (E18), anti-Cdc2 monoclonal (p34 17), anti-Cdc6 monoclonal (180.2) (all from Santa Cruz), anti-phospho-pRb (S807/S811) polyclonal, anti-phospho-pRb (S608) polyclonal, anti-phospho-pRb (S780) polyclonal, anti-phospho-pRb (S795) (all from Cell Signalling), anti-phospho-pRb (S249/T252) polyclonal, anti-phospho-pRb (T826) polyclonal (both from Invitrogen), anti-Set9 polyclonal (Cell signalling) and anti-HA.11 monoclonal (Covance). The anti-MeK810 peptide antibody was generated by immunizing rabbits with a mono-methylated peptide (810m—ISPL[KMe]SPYKISEGLC) (Sigma). Serum was collected and affinity purified over a methylated and non-methylated peptide column. Immunoblot images were scanned into Photoshop (Adobe) and quantitated using Scion Image software (Scion Corporation). For immunoprecipitation, U2OS cells were transfected with HA-pRb/HA-pRb K810R/HA-pRb S807A/S811A and/or myc-Set7/9 where indicated for 24 h. Cells were then treated with the indicated amount of etoposide (Sigma) for further 16 h prior to lysis in modified RIPA (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4; 1% Igepal CA-630; 150 mM NaCl; 1 mM EDTA; 1 mM NaF; 1 mM Na3VO4; 1 mM PMSF; protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)). Cell extracts were incubated with anti-HA Ab or control mouse IgG for 1–2 h at 4°C. Endogenous pRb immunoprecipitations were performed using anti-pRb Ab. Protein G sepharose (Sigma) was added to the extracts overnight at 4°C. Protein was washed in modified RIPA (0.1% Igepal) and eluted with 2 × SDS-loading buffer.

In vitro protein methylation assays

In all, 1 μg core histones (Roche), 30 μg of pRb peptide or 1–2 μg of bacterially expressed recombinant GST-pRb or GST-pRb K810R were incubated with 0.5 μg of recombinant GST-Set7/9 in HMT buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8; 20 mM KCl; 5 mM DTT; 1 mM EDTA; 1 μCi [3H]-SAM (GE Life Sciences)) for 1 h at 30°C. Reactions were spotted onto P81 filters (Whatman) and washed three times in 50 mM NaHCO3 (pH 9.2) and once in acetone before analysis by scintillation counting. Alternatively, reactions were halted by addition of 2 × SDS-loading dye. Radio-labelled protein was separated by SDS–PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose before analysis by autoradiography.

In vitro protein phosphorylation assays

Reactions were performed as above, except 150 ng of baculovirus-expressed cyclin D1/Cdk4 (Invitrogen) was used in assay buffer containing 25 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5; 0.01% Triton X-100; 10 mM MgCl2; 0.5 mM Na3VO4; 2.5 mM DTT, 0.5 mM EGTA and 200 μM cold ATP (Sigma). In all, 25 μg of pRb peptides were used in similar reactions prior to direct spotting onto nitrocellulose for immunoblot.

Sequential in vitro methylation/phosphorylation assays

In all, 0.5 μg of GST-pRb was incubated with 3 μg GST-Set7/9 in HMT buffer for 3 h at 30°C. A fraction of this mix was analysed by scintillation counting to confirm methylation of pRb had occurred, while 200 μM cold ATP and 150 ng cyclin D1/Cdk4 was added to the remaining material for further 30 min. Reactions were halted as above and analysed by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies.

Flow cytometry

Cells were harvested using cell dissociation solution (Sigma) and washed in PBS prior to fixation in 70% ethanol in PBS at 4°C for 1 h. Fixed cells were PBS washed and resuspended in 100 μg/ml propidium iodide (Sigma) containing 125 units/ml ribonuclease A (Sigma). Cell cycle analysis was performed using a FACScan flow cytometer and CellQuest software package (Becton Dickinson). A minimum of 1 × 104 events were collected for each sample and all conditions were performed in triplicate.

Mass spectrometry analysis

GST-pRb was used in an in vitro methylation reaction using unlabelled SAM (Sigma). The reaction was halted by addition of NuPage LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen) and separated by SDS–PAGE on NuPage 10% Bis-Tris pre-cast gels (Invitrogen) using NuPage MOPS SDS running buffer (Invitrogen). Gels were stained with GelCode Blue (Thermo) and the GST-pRb protein band was excised for in-gel tryptic digestion as described previously (Jansson et al, 2008). The individual tryptic peptides were analysed by LC–MS/MS using a high-capacity ion trap tandem mass spectrometer (HCTplus™, Bruker Daltonics) coupled to a C18 reversed phase HPLC system (Dionex/LC Packings) as described (Batycka et al, 2006). MS/MS spectra were analysed using the Mascot Software package (version 2.2, Matrixscience) and Bruker DataAnalysis software (version 2.4), following the guidelines reported previously (Taylor and Goodlett, 2005).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

SAOS2 cells were transfected with empty vector, HA-pRb or HA-pRb K810R (4 μg) for 48 h. Cells were then cross-linked with formaldehyde and ChIP samples were prepared as described previously (Munro et al, 2010). Immunoprecipitations were performed using 2 μg of anti-HA antibody (HA.11, Covance). Immunoprecipitate and inputs were reverse cross-linked, DNA purified and analysed by PCR.

Luciferase reporter assays

SAOS2 cells were transfected with HA-pRb or HA-pRb K810R (2 μg), together with HA-E2F-1 (300 ng), cyclinE-luciferase reporter plasmid (300 ng) and pCMV-βgal (300 ng) as an internal control. After 48 h, extracts were prepared and analysed as described previously (Chan et al, 2001). All conditions were performed in triplicate.

pRb stable cell lines

pRb (379–928) and pRb-K810R (379–928) inducible U2OS cell lines were generated by transfecting pTRE2hyg-pRb and pTRE2hyg-pRb-K810R into a Tet-ON U2OS cell line (Clontech) and selection with hygromycin B (Invitrogen) in accordance with the Tet-ON inducible cell line system instructions (Clontech). pRb protein expression was induced using 1 μg/ml doxycycline (Invitrogen) for 48 h.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Rosemary Williams for help in the preparation of the manuscript and Wen Hwa Lee for help with the figures. Work in our laboratories is supported by CRUK, MRC, LRF, AICR, EU and the Oxford NIHR Musculoskeletal Biomedical Research Unit. The Structural Genomics Consortium is a registered charity (number 1097737) that receives funds from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, the Canadian Foundation for Innovation, Genome Canada through the Ontario Genomics Institute, GlaxoSmithKline, Karolinska Institutet, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Ontario Innovation Trust, the Ontario Ministry for Research and Innovation, Merck and Co., Inc., the Novartis Research Foundation, the Swedish Agency for Innovation Systems, the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research and the Wellcome Trust.

Author contributions: SMC designed and performed the majority of the experiments and data analysis. SM provided additional experimental data. BK performed the mass spectrometry. UO performed the structural modelling. NBLT conceived of the project, guided the research and wrote the paper.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Bandara LR, Adamczewski JP, Hunt T, La Thangue NB (1991) Cyclin A and the retinoblastoma gene product complex with a common transcription factor. Nature 352: 249–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batycka M, Inglis NF, Cook K, Adam A, Fraser-Pitt D, Smith DG, Main L, Lubben A, Kessler BM (2006) Ultra-fast tandem mass spectrometry scanning combined with monolithic column liquid chromatography increases throughput in proteomic analysis. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 20: 2074–2080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blais A, Dynlacht BD (2007) E2F-associated chromatin modifiers and cell cycle control. Curr Opin Cell Biol 19: 658–662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botz J, Zerfass-Thorne K, Spitkovaky D, Delius H, Vogt B, Eilers M, Hatzigeorgiou A, Jansen-Durr P (1996) Cell cycle regulation of the murine cyclin E gene depends on an E2F binding site in the promoter. Mol Cell Biol 16: 3401–3409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown NR, Noble ME, Endicott JA, Johnson LN (1999) The structural basis for specificity of substrate and recruitment peptides for cyclin-dependent kinases. Nat Cell Biol 1: 438–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan HM, Krstic-Demonacos M, Smith L, Demonacos C, La Thangue NB (2001) Acetylation control of the retinoblastoma tumour-suppressor protein. Nat Cell Biol 3: 667–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuikov S, Kurash JK, Wilson JR, Xiao B, Justin N, Ivanov GS, McKinney K, Tempst P, Prives C, Gamblin SJ, Barlev NA, Reinberg D (2004) Regulation of p53 activity through lysine methylation. Nature 432: 353–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Classon M, Harlow E (2002) The retinoblastoma tumour suppressor in development and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2: 910–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell-Crowley L, Harper JW, Goodrich DW (1997) Cyclin D1/Cdk4 regulates retinoblastoma protein-mediated cell cycle arrest by site-specific phosphorylation. Mol Biol Cell 8: 287–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson N (1998) The regulation of E2F by pRB-family proteins. Genes Dev 12: 2245–2262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el-Deiry WS, Harper JW, O'Connor PM, Velculescu VE, Canman CE, Jackman J, Pietenpol JA, Burrell M, Hill DE, Wang Y, Wiman KG, Mercer WE, Kastan MB, Kohn KW, Elledge SJ, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B (1994) WAF1/CIP1 is induced in p53-mediated G1 arrest and apoptosis. Cancer Res 54: 1169–1174 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezhevsky SA, Ho A, Becker-Hapak M, Davis PK, Dowdy SF (2001) Differential regulation of retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein by G(1) cyclin-dependent kinase complexes in vivo. Mol Cell Biol 21: 4773–4784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischle W, Tseng BS, Dormann HL, Ueberheide BM, Garcia BA, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Funabiki H, Allis CD (2005) Regulation of HP1-chromatin binding by histone H3 methylation and phosphorylation. Nature 438: 1116–1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacinti C, Giordano A (2006) RB and cell cycle progression. Oncogene 25: 5220–5227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson M, Durant ST, Cho EC, Sheahan S, Edelmann M, Kessler B, La Thangue NB (2008) Arginine methylation regulates the p53 response. Nat Cell Biol 10: 1431–1439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa M, Higashi H, Jung HK, Suzuki-Takahashi I, Ikeda M, Tamai K, Kato J, Segawa K, Yoshida E, Nishimura S, Taya Y (1996) The consensus motif for phosphorylation by cyclin D1-Cdk4 is different from that for phosphorylation by cyclin A/E-Cdk2. EMBO J 15: 7060–7069 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen KE, Booth D, Naderi S, Sever-Chroneos Z, Fribourg AF, Hunton IC, Feramisco JR, Wang JY, Knudsen ES (2000) RB-dependent S-phase response to DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol 20: 7751–7763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latham JA, Dent SY (2007) Cross-regulation of histone modifications. Nat Struct Mol Biol 14: 1017–1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macaluso M, Montanari M, Giordano A (2006) Rb family proteins as modulators of gene expression and new aspects regarding the interaction with chromatin remodelling enzymes. Oncogene 25: 5263–5267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malumbres M, Barbacid M (2009) Cell cycle, CDKs and cancer: a changing paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer 9: 153–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham D, Munro S, Soloway J, O'Connor DP, La Thangue NB (2006) DNA-damage-responsive acetylation of pRb regulates binding to E2F-1. EMBO Rep 7: 192–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C, Zhang Y (2005) The diverse functions of histone lysine methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6: 838–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittnacht S (1998) Control of pRB phosphorylation. Curr Opin Genet Dev 8: 21–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DO (1997) Cyclin-dependent kinases: engines, clocks, and microprocessors. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 13: 261–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro S, Khaire N, Inche A, Carr S, La Thangue NB (2010) Lysine methylation regulates the pRb tumour suppressor protein. Oncogene 29: 2357–2367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen DX, Baglia LA, Huang SM, Baker CM, McCance DJ (2004) Acetylation regulates the differentiation-specific functions of the retinoblastoma protein. EMBO J 23: 1609–1618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishioka K, Chuikov S, Sarma K, Erdjument-Bromage H, Allis CD, Tempst P, Reinberg D (2002) Set9, a novel histone H3 methyltransferase that facilitates transcription by precluding histone tail modifications required for heterochromatin formation. Genes Dev 16: 479–489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raynaud FI, Whittaker SR, Fischer PM, McClue S, Walton MI, Barrie SE, Garrett MD, Rogers P, Clarke SJ, Kelland LR, Valenti M, Brunton L, Eccles S, Lane DP, Workman P (2005) In vitro and in vivo pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationships for the trisubstituted aminopurine cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors olomoucine, bohemine and CYC202. Clin Cancer Res 11: 4875–4887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr CJ (2000) The Pezcoller lecture: cancer cell cycles revisited. Cancer Res 60: 3689–3695 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens C, La Thangue NB (2003) E2F and cell cycle control: a double-edged sword. Arch Biochem Biophys 412: 157–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaki T, Fukasawa K, Suzuki-Takahashi I, Semba K, Kitagawa M, Taya Y, Hirai H (2005) Preferences for phosphorylation sites in the retinoblastoma protein of D-type cyclin-dependent kinases, Cdk4 and Cdk6, in vitro. J Biochem 137: 381–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor GK, Goodlett DR (2005) Rules governing protein identification by mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 19: 3420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida C, Miwa S, Kitagawa K, Hattori T, Isobe T, Otani S, Oda T, Sugimura H, Kamijo T, Ookawa K, Yasuda H, Kitagawa M (2005) Enhanced Mdm2 activity inhibits pRB function via ubiquitin-dependent degradation. EMBO J 24: 160–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Heuvel S, Dyson NJ (2008) Conserved functions of the pRB and E2F families. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9: 713–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal A, Koff A (2000) Cell-cycle inhibitors: three families united by a common cause. Gene 247: 1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg RA (1995) The retinoblastoma protein and cell cycle control. Cell 81: 323–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JR, Jing C, Walker PA, Martin SR, Howell SA, Blackburn GM, Gamblin SJ, Xiao B (2002) Crystal structure and functional analysis of the histone methyltransferase SET7/9. Cell 111: 105–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalmas LP, Zhao X, Graham AL, Fisher R, Reilly C, Coutts AS, La Thangue NB (2008) DNA-damage response control of E2F7 and E2F8. EMBO Rep 9: 252–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.