Multiple elements in the eIF4G1 N-terminus promote assembly of eIF4G1•PABP mRNPs in vivo

The translation initiation factor eIF4G1 mediates mRNA circularization via interaction with poly(A)-binding protein (PABP) and the cap-binding factor eIF4E. This study reveals that PABP/eIF4G1-mediated closed-loop formation is not essential for translation, as this interaction is only one of several contact points that are required for eIF4G1/mRNA complex formation.

Keywords: eIF4G, initiation, translation, PABP, yeast

Abstract

eIF4G is the scaffold subunit of the eIF4F complex, whose binding domains for eIF4E and poly(A)-binding protein (PABP) are thought to enhance formation of activated eIF4F•mRNA•PABP complexes competent to recruit 43S pre-initiation complexes. We found that the RNA-binding region (RNA1) in the N-terminal domain (NTD) of yeast eIF4G1 can functionally substitute for the PABP-binding segment to rescue the function of an eIF4G1-459 mutant impaired for eIF4E binding. Assaying RNA-dependent PABP–eIF4G association in cell extracts suggests that RNA1, the PABP-binding domain, and two conserved elements (Box1 and Box2) between these segments have overlapping functions in forming native eIF4G•mRNA•PABP complexes. In vitro experiments confirm the role of RNA1 in stabilizing eIF4G–mRNA association, and further indicate that RNA1 and Box1 promote PABP binding, in addition to RNA binding, by the eIF4G1 NTD. Our findings indicate that PABP–eIF4G association is only one of several interactions that stabilize eIF4F•mRNA complexes, and emphasize that closed-loop mRNP formation via PABP–eIF4G interaction is non-essential in vivo. Interestingly, two other RNA-binding regions in eIF4G1 have critical functions downstream of eIF4F•mRNA assembly.

Introduction

Selection of the translation initiation codon in eukaryotic mRNA generally occurs by the scanning mechanism, which begins with recruitment to the small (40S) ribosomal subunit of methionyl initiator tRNA in a ternary complex with eIF2•GTP in a reaction stimulated by several other initiation factors, namely, eIF1, eIF1A, eIF3, and eIF5. The resulting 43S pre-initiation complex (PIC) binds to activated mRNA, which is bound at its m7G-cap by the eIF4F complex, comprising cap-binding protein eIF4E, eIF4G, and RNA helicase eIF4A, thought to provide a single-stranded binding site for the ribosome near the mRNA 5′ end. eIF4G is a scaffold protein that, for the mammalian version, harbours binding domains in its N-terminus for poly(A)-binding protein (PABP) and eIF4E, and in its middle and C-terminal regions for eIF4A and eIF3. The eIF4G–eIF3 interaction is thought to create a protein bridge between the activated eIF4F•mRNA•PABP complex and the 43S PIC (LeFebvre et al, 2006). Budding yeast contains two eIF4G isoforms that are ∼50% identical in sequence to one another and also related to eIF4G proteins from other eukaryotes (Goyer et al, 1993). Although both yeast isoforms interact with PABP (Tarun and Sachs, 1996; Tarun et al, 1997), eIF4E (Altmann et al, 1989; Goyer et al, 1989), and eIF4A (Dominguez et al, 1999; Neff and Sachs, 1999), direct interactions with eIF3 have not been detected, and interactions with eIF5 and eIF1 might functionally substitute for eIF3–eIF4G interaction in mRNA recruitment in this organism (He et al, 2003).

Eliminating the yeast gene encoding eIF4G1 (TIF4631), but not that encoding eIF4G2 (TIF4632), confers a slow-growth (Slg−) phenotype (de la Cruz et al, 1997) and translation initiation defect (Clarkson et al, 2010), consistent with the fact that eIF4G1 is expressed at higher levels than is eIF4G2 (encoded by TIF4632) (Tarun and Sachs, 1996; von der Haar and McCarthy, 2002; Ghaemmaghami et al, 2003; Clarkson et al, 2010). Indeed, strains engineered to express only eIF4G2 or eIF4G1 at a level equivalent to the combination of both isoforms in wild type (WT) display no growth or translation initiation defects (Clarkson et al, 2010). These results, together with the fact that simultaneously deleting both TIF4631 and TIF4632 is lethal (Goyer et al, 1993), indicate that eIF4G1 or eIF4G2 can function interchangeably to execute the critical function of eIF4G in translation initiation in yeast.

The cap structure and poly(A) tail make independent contributions to increasing the translational efficiency of mRNAs (Sachs, 2000), and in vitro experiments suggest that the cap and PABP/poly(A) tail have overlapping functions in mRNA recruitment by the 43S PIC in yeast extracts (Tarun and Sachs, 1995). Consistent with this, mutations impairing cap binding by eIF4E and poly(A) binding by PABP are synthetically lethal in yeast (Kessler and Sachs, 1998). There is also genetic evidence that cap–poly(A) cooperation depends on simultaneous binding of eIF4E and PABP to their respective binding regions in eIF4G. Thus, in a yeast mutant lacking eIF4G2, deletion of the N-terminal 300 amino acids (aa) of eIF4G1 (tif4631-ΔN300), including the PABP-binding domain (Tarun and Sachs, 1996), was lethal only when combined with the temperature-sensitive mutation tif4631-459, which substitutes two conserved leucines in the eIF4E-binding motif of eIF4G1. Both the ΔN300 truncation and a four-residue substitution in the PABP-binding region of eIF4G1 (mutation −213) abolished the stimulatory effect of the poly(A) tail on translation in vitro (Tarun et al, 1997). There is evidence that cap–poly(A) cooperation in mammalian extracts likewise depends on eIF4G–PABP interaction (Michel et al, 2000), and that mutationally disrupting eIF4G–PABP interaction reduces 48S PIC assembly, 80S initiation complex formation, and overall translational efficiency in cell extracts (Kahvejian et al, 2005; Hinton et al, 2007).

It is thought that cap–poly(A) cooperation involves the ability of eIF4E and PABP, by interacting with the two free ends of mRNA and their respective binding domains in eIF4G, to form a circular ‘closed-loop' complex (Sachs, 2000). Indeed, there is evidence that PABP stimulates eIF4F•mRNA interaction in a manner dependent on direct eIF4G–PABP association in extracts of mammalian (Kahvejian et al, 2005) and yeast cells (Amrani et al, 2008). Other reports indicate that PABP binding to eIF4G allosterically enhances eIF4F binding to the cap structure for yeast (von Der Haar et al, 2000) and plant factors (Wei et al, 1998), although this may not apply to mammals (Hinton et al, 2007).

There is evidence that the RNA-binding activity lodged in the central region of mammalian eIF4G also enhances eIF4F binding to the capped 5′ end of mRNA in vitro, presumably by contributing an additional contact of eIF4F with mRNA besides the eIF4E–cap association (Yanagiya et al, 2009). In fact, it was found that the eIF4E–cap interaction adds little to the binding affinity of purified eIF4F for mRNAs >60 nt in length (Kaye et al, 2009). However, unlike eIF4E–cap interaction, eIF4G presumably must compete with other general RNA-binding proteins for binding to mRNA in vivo. The ability of eIF4G to also interact with the PABP-bound poly(A) tail apparently provides another means of out-competing general RNA-binding proteins (that do not interact with PABP). Thus, by simultaneously interacting with eIF4E/cap, PABP/poly(A) tail, and the body of mRNA, eIF4G can assemble a highly stable mRNP (Svitkin et al, 2009). It is unclear whether the PABP–eIF4G interaction is important because it enables mRNA circularization per se or, rather, because of its participation in cooperative binding of eIF4G to mRNA.

The key evidence that PABP–eIF4G interaction is essential for yeast cell viability when eIF4E–eIF4G interaction is impaired is that the −459 mutation in the eIF4E-binding site of eIF4G1 is synthetically lethal with the N-terminal truncation (−ΔN300) that eliminates the PABP-binding domain of eIF4G1, but not in combination with a smaller truncation (−ΔN187) that leaves the PABP-binding domain intact (Tarun et al, 1997). However, these results could be explained differently by proposing that eliminating a distinct function carried out by aa 1–187 simultaneously with removing the PABP-binding domain between aa 188–299 (Tarun et al, 1997) is responsible for the synthetic lethality of the −459,ΔN300 double mutation. It is also unknown whether combining mutations in the eIF4E- and PABP-binding domains in eIF4G1 have additive effects on assembly of eIF4F•mRNA•PABP complexes in vivo.

In this report, we show that eliminating the canonical PABP-binding domain of eIF4G1 is not sufficient for synthetic lethality with the −459 mutation in the eIF4E-binding site. Rather, the extreme N-terminus of eIF4G1 (aa 1–82), which has RNA-binding activity (Berset et al, 2003) and is henceforth denoted RNA1, must be removed together with the PABP-binding domain to produce a lethal reduction in the function of the eIF4G1-459 mutant protein. We further show that the region between RNA1 and the PABP-binding domain contains two segments conserved in Saccharomyces eIF4G homologs, dubbed Box1 and Box2, that also functionally overlap with the PABP-binding domain in vivo. Moreover, we present biochemical evidence that RNA1, Box1, Box2, and the PABP-binding domain all contribute to the assembly of native eIF4G•mRNA•PABP complexes present in cell extracts. Interestingly, we also found that both the RNA1 and the Box1 segments enhance direct PABP binding to the canonical PABP-binding domain in the eIF4G1 N-terminal domain (NTD). Our findings indicate that, while the eIF4G–PABP interaction is important, RNA binding by the eIF4G1 NTD also makes a significant, overlapping contribution to forming eIF4G•mRNA complexes in vivo. These results suggest that the role of eIF4G–PABP interaction in closed-loop formation is not fundamentally important and only represents one of several interactions that stabilize eIF4G binding to mRNA.

Results

Evidence that the PABP-binding, Box1–Box2, and RNA1 regions in the NTD have overlapping functions with the eIF4E-binding domain in eIF4G1

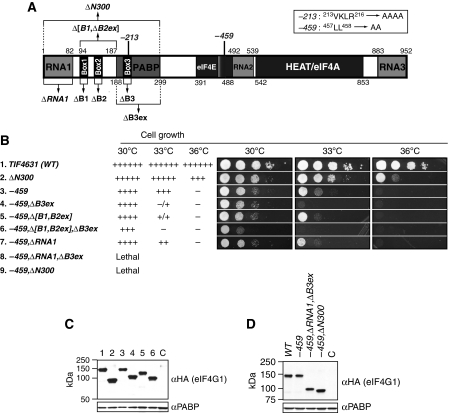

The –ΔN300 mutation removes the first 300 aa of eIF4G1, including the known PABP-binding domain between aa 188–299 (Tarun and Sachs, 1996, 1997) (Figure 1A). As shown previously, in a (tif4632Δ) strain lacking eIF4G2, −ΔN300 confers a moderate slow-growth phenotype (Slg−) at 30°C, but a more substantial growth defect at 36°C (Figure 1B, row 2). The −459 mutation, which makes alanine substitutions of conserved residues (L457, L458) in the eIF4E-binding motif (Figure 1A), also confers an Slg− phenotype at 30°C but is lethal at 36°C (Figure 1B, row 3). As reported previously, combining these two mutations is synthetically lethal at all temperatures (Tarun et al, 1997) (Figure 1B, row 9). To determine whether the lethal effect of combining the –ΔN300 and −459 mutations can be attributed simply to eliminating the PABP-binding domain between aa 188–299 (Tarun and Sachs, 1996; Tarun et al, 1997), we combined −459 with an internal deletion that removes only this region, dubbed (for reasons explained below) the −ΔB3ex mutation for ‘deletion of extended region around homology Box3' (Figure 1A). Surprisingly, the resulting −459,ΔB3ex double mutant is viable and grows indistinguishably from the −459 single mutant at 30°C, although it grows much more slowly than the −459 mutant at the semi-permissive temperature of 33°C (Figure 1B, rows 3 and 4). This exacerbated growth defect is not attributable to the instability of the mutant protein, as western analysis of whole-cell extracts (WCEs) revealed no reduction in the steady-state level of eIF4G1 conferred by the −459,ΔB3ex double mutation (Figure 1C, lanes 1, 3, and 4). Thus, eliminating the canonical PABP-binding domain does not account for the lethal effect of removing the N-terminal 300 residues from the eIF4G1-459 mutant protein. (To facilitate comparisons of different mutants, the growth phenotypes of all mutants are summarized in Supplementary Table SI of the Supplementary data in addition to being presented in the relevant regular figures).

Figure 1.

Deletion of the PABP-binding domain is not lethal in combination with the −459 substitution in the eIF4E-binding domain of eIF4G1 in cells lacking eIF4G2. (A) Schematic representation of yeast eIF4G1, showing the locations of RNA-binding domains (RNA1–RNA3), canonical PABP-binding domain (PABP), eIF4E-binding domain (eIF4E), HEAT repeat domain that binds eIF4A (HEAT/eIF4A), and locations of Box1 (aa 94–111), Box2 (aa 128–150), Box3 (aa 197–224), the [Box1,Box2ext] region (aa 94–187), Box3ext region (aa 188–300), and point mutations −213 and −459. The regions removed by the indicated deletions are indicated with brackets. (B) Growth phenotypes of tif4632Δ strains harbouring the indicated HA-tagged TIF4631 alleles on a low-copy TRP1 plasmid, derived by plasmid shuffling from strain YAS2282. Serial 10-fold dilutions of each strain were spotted on SC-Trp and incubated at 30, 33, or 36°C for 2 days. Amounts of growth at different dilutions were summarized as 6+ (WT growth) to 1+, −/+, or – (no growth). The following strains were employed for rows 1–7, respectively: EPY88, EPY206, EPY52, EPY82, EPY87, EPY86, and EPY93. (C) Expression of HA-tagged mutant eIF4G1 proteins. Strains described in (B) were grown at 30°C in SC-Trp and WCEs were subjected to western blot analysis with anti-HA and PABP antibodies (to control for amounts of total protein). Lanes 1–6 contain WCEs from the strains described in rows 1–6, respectively, in panel (B). The WCE in lane C derives from strain YAS2069 harbouring untagged TIF4631. (D) Expression of lethal mutant proteins. Strains harbouring the indicated WT or mutant tif4631-HA alleles and untagged TIF4632 were grown in SC-Trp,-Ura, and subjected to western blot analysis as in (C), employing the following strains: EPY132, EPY133, EPY102, EPY205, and EPY161 (lane C, untagged control).

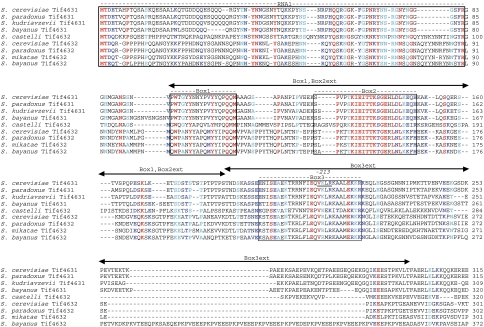

We considered next the possibility that the region immediately upstream of the PABP-binding domain contributes to eIF4G1 function. This idea was supported by a multiple sequence alignment of Saccharomyces cerevisiae eIF4G1 and eIF4G2 with eIF4G proteins from closely related Saccharomyces species (Figure 2), which revealed two conserved segments between aa 94–111 and aa 128–150, dubbed Boxes 1 and 2, respectively. A third region of strong sequence similarity, designated Box3, maps between aa 197–224 within the PABP-binding domain (Figure 2), and includes the four residues, V213–K–L–R216, whose substitution with alanines by the −213 mutation impaired binding of PABP to recombinant eIF4G1 in vitro (Tarun et al, 1997). We found that deleting aa 94–187, encompassing Box1, Box2, and a portion of the residues between Box2 and Box3 (the [Box1,Box2ext] region, Figures 1A and 2), only slightly exacerbates the Slg− phenotype of the −459 mutation (Figure 1B, cf. rows 5 and 3 at 33°C); however, this Δ[B1,B2ex] mutation clearly intensifies the growth defect conferred by the −459,ΔB3ex double mutation in the resulting triple mutant (Figure 1B, cf. rows 6 and 4 at 30°C), without reducing eIF4G1 expression (Figure 1C, lanes 4 and 6). These findings suggest that sequences in the [Box1,Box2ext] region functionally overlap with the canonical PABP-binding region (aa 188–299) in eIF4G1.

Figure 2.

Identification of conserved sequence elements Box1, Box2, and Box3 in the eIF4G1 NTD. ClustalW multiple sequence alignments of the N-terminal region of eIF4G proteins from the indicated Saccharomyces species constructed using the Fungal Alignment Viewer on the Saccharomyces genome database (SGD) at http://www.yeastgenome.org/HCContents.shtml. RNA1, and Boxes 1, 2, and 3 are enclosed in boxes and the residues altered by tif4631–213 in Box3 are underlined.

The fact that the −459,Δ[B1,B2ex],ΔB3ex triple mutant is viable at 30°C, whereas the −459,ΔN300 mutant is inviable (Figure 1B, rows 6 and 9) implies that the region encompassing RNA1 (residues 1–82) also functionally overlaps with these other three regions in the eIF4G1 NTD. Trachsel and colleagues showed previously that the RNA1 fragment binds single-stranded RNA with a Kd of ∼5 μM, but that its elimination by –ΔRNA1 from otherwise WT eIF4G1 had no effect on cell growth (Berset et al, 2003). We also observed that deleting RNA1 alone has no effect on growth (Supplementary Table SI), and that it only slightly exacerbates the Slg− phenotype of the −459 mutation in the −459,ΔRNA1 double mutant (Figure 1B, rows 3 and 7 at 33°C). Importantly, however, combining –ΔRNA1 and –ΔB3ex with −459 in a triple mutant is lethal (Figure 1B, row 8), and western analysis of cells coexpressing untagged WT eIF4G2 (to overcome the lethality) revealed no effect of combining these mutations on HA-eIF4G1 expression (Figure 1D; Supplementary Figure S1 in Supplementary data). (Note that Supplementary Figure S1 contains the western analysis of all eIF4G1 mutant proteins examined in this study.) Thus, simultaneously eliminating RNA1 and the PABP-binding domain is required to recapitulate the lethality of the –ΔN300 truncation of the eIF4G1-459 mutant protein.

Evidence that Box1, Box2, and Box3 all contribute to eIF4G1•PABP mRNP assembly in vivo

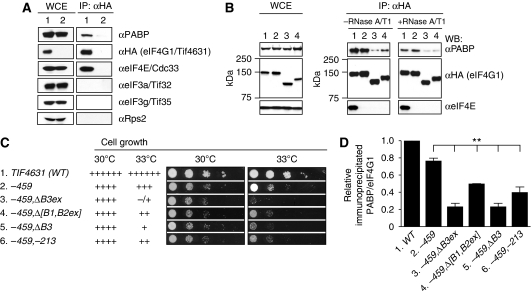

To evaluate the contributions of the eIF4E-binding domain and the multiple conserved regions in the eIF4G1 NTD on formation of eIF4F•PABP mRNPs in vivo, we examined the interaction of PABP with HA-tagged eIF4G1 by coimmunoprecipitation analysis of WCEs. As shown in Figure 3A, a fraction of PABP and eIF4E specifically coimmunoprecipitates with HA-tagged WT eIF4G1 (IP panel, lanes 1 and 2), whereas two eIF3 subunits and a 40S component Rps2 do not, implying that the eIF4F•PABP complexes are not stably associated with 43S PICs in WCEs. Furthermore, the amount of PABP, but not eIF4E, that coimmunoprecipitated with HA-eIF4G1 was greatly diminished by treatment of immune complexes with RNAses A and T1 (Figure 3B, IP panels, αPABP blot, cf. lane 1 in –RNAse versus +RNAse panels). This last result implies that the eIF4G1–PABP interaction in WCEs is strongly stabilized by mRNA. Tarun and Sachs (1996) also reported that coimmunoprecipitation of native PABP and eIF4G is RNAase sensitive, and that PABP binding to recombinant eIF4G in vitro is likewise sensitive to RNAse treatment of the eIF4G. These results suggested that direct PABP–eIF4G interaction is relatively weak and must be stabilized by mutual binding of both proteins to RNAs that copurify with eIF4G from bacteria. Accordingly, we likewise interpret the RNAse-sensitive eIF4G1•PABP complexes recovered by immunoprecipitation as representing native mRNPs containing eIF4F and PABP tethered to the same mRNA molecules. Thus, to quantify the effects of eIF4G1 mutations on eIF4F•PABP mRNP levels, we measured the western blot signals for PABP and eIF4G1 recovered in replicate immunoprecipitations conducted without RNAse treatment, calculated the PABP:eIF4G1 ratios for each mutant, and normalized the results to the corresponding PABP:eIF4G1 ratio for the WT strain.

Figure 3.

The [Box1Box2ext] region in addition to the canonical PABP-binding domain (Box3ext region) enhances native eIF4G1·PABP mRNP formation. (A) eIF4G1 coimmunoprecipitates with PABP and eIF4E, but not with eIF3 or Rps2. Strains EPY88 and YAS2069 containing HA-eIF4G1 (lane 1) or untagged eIF4G1 (lane 2), respectively, were cultured in SC-Trp and WCEs were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies. The immune complexes were resolved by 4–20% SDS–PAGE and subjected to western analysis using antibodies listed on the right, examining 5% of input (WCE) and 22% of immunoprecipitates (IP: αHA). (B) eIF4G1–PABP interaction in WCEs is sensitive to RNase treatment. HA-tagged eIF4G1 was immunoprecipitated as in (A) from strains EPY88, EPY52, EPY82, and EPY87 containing, respectively, WT (lane 1), –459 (lane 2), −459,ΔB3ex (lane 3), or –459,Δ[B1,B2ex] (lane 4). TIF4631-HA alleles and immune complexes were incubated at 26°C for 30 min in the presence or absence of RNases A and T1 before western analysis. (C) Growth phenotypes for strains with the indicated TIF4631-HA genotypes were assessed as in Figure 1B, employing strains EPY88, EPY52, EPY82, EPY87, EPY112, and EPY46. (D) Three independent coimmunoprecipitation experiments were conducted without RNAase treatment on the indicated strains and the western blot signals for PABP and eIF4G1 were quantified using NIH ImageJ software. PABP:eIFG1 ratios were calculated and normalized to the corresponding ratio for the WT strain. The mean±s.e.m. calculated from the replicate experiments is plotted. Statistical significance of the differences between the −459 and indicated mutants were assessed using an unpaired Student's t-test (**P<0.01).

Using this approach, we found that the −459 mutation in the eIF4E-binding domain abolishes coimmunoprecipitation of eIF4E with HA-eIF4G1, but produces only a small (∼20%) reduction in the mean PABP:eIF4G1 ratio in the immune complexes (Figure 3B, IP/–RNase panel, cf. lanes 1 and 2; see quantification in Figure 3D, columns 1 and 2). This finding suggests that eIF4G and PABP form mRNPs with relatively high efficiency in the absence of a stable interaction between eIF4E and eIF4G. Importantly, combining −459 with deletion of either the PABP-binding domain (–ΔB3ex) or the [Box1,Box2ext] region (–Δ[B1,B2ex]) further reduces the yield of eIF4G1•PABP mRNPs recovered from WCEs to ∼25% and 50% of the WT level, respectively (Figure 3B, IP, –RNAse, cf. lanes 1, 3, and 4; Figure 3D, lanes 1, 3, and 4). These findings suggest that the Box1–Box2 region functions in conjunction with the PABP-binding domain to enhance the assembly or stability of eIF4G1•PABP mRNPs.

To dissect in greater detail the residues in the canonical PABP-binding domain required for eIF4G1•PABP mRNP assembly, we compared the effects of removing all 112 residues of the Box3ext region (−ΔB3ex) with those of eliminating only the 28 residues in Box3 (−ΔB3), or with those of alanine substitutions of the four conserved residues in Box3 altered by the −213 mutation (Tarun and Sachs, 1997). Results in Figure 3C reveal that −ΔB3 and −213 have a less severe effect than does removing the entire PABP-binding domain by −ΔB3ex in exacerbating the growth defect at 33°C conferred by the −459 mutation (33°C, rows 2–3 and 5–6). Consistent with the growth phenotypes, the −213,−459 double mutation produces a smaller reduction than does the −459,ΔB3ex combination in the yield of immunoprecipitated eIF4G1•PABP mRNPs (Figure 3D, lanes 2, 3, 6). These results indicate that the −213 mutation does not completely inactivate the PABP-binding domain in eIF4G1, and at least on the basis of growth phenotypes, –ΔB3ex exceeds the effect of –ΔB3 in exacerbating the effect of the −459 mutation. The latter suggests that residues surrounding Box3 in the Box3ext segment might contribute to the function of the PABP-binding domain.

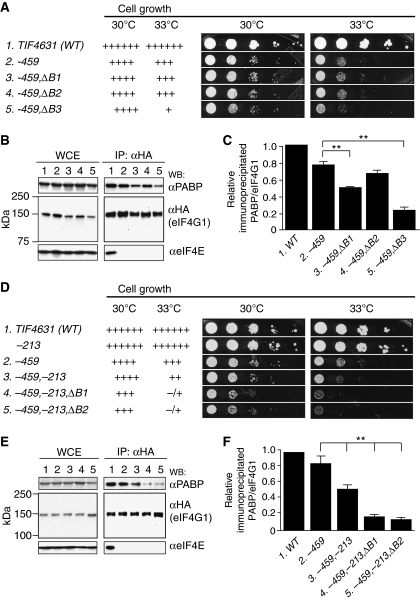

To assess the relative importance of Boxes 1–3 in eIF4G1•PABP mRNP formation, we compared the effects of combining mutation −459 with each of the three small deletions (−ΔB1, –ΔB2, or −ΔB3) that remove Boxes 1–3 individually. Unlike −ΔB3, neither −ΔB1 nor –ΔB2 exacerbates the Slg− phenotype conferred by −459 (Figure 4A). Consistent with this, −ΔB2 has only a small effect on eIF4G1•PABP mRNP levels in the coimmunoprecipitation assay (Figure 4B and C, lanes 2 and 4). Furthermore, while −ΔB1 reduces eIF4G1•PABP mRNP levels, it has a smaller effect than does −ΔB3 (Figure 4B and C, lanes 3 and 5). Together, these findings indicate that Box1 and Box2 are less important than Box3 in promoting eIF4G1•PABP mRNP assembly and cell growth. This conclusion is consistent with the above findings that eliminating the [Box1,Box2ext] region is less deleterious to cell growth and eIF4G1•PABP mRNP assembly than is removing the Box3ext region (Figure 3C and D).

Figure 4.

Box1 and Box2 functionally overlap with the canonical PABP-binding domain (Box3ext) of eIF4G1 in promoting cell growth and native eIF4G1·PABP mRNP formation. (A) Growth phenotypes for strains with the indicated TIF4631-HA genotypes were assessed as in Figure 1B, employing strains EPY88, EPY52, EPY130, EPY131, and EPY112. (B, C) Coimmunoprecipitation analysis conducted without RNAse treatment as in Figure 3B and D for strains listed in (A). Lane designations in (B) are identical to row designations in (A) and column designations in (C) (**P<0.01). (D–F) Analyses conducted as in (A–C) for the following strains of indicated TIF4631-HA genotype: EPY88, YAS2075, EPY52, EPY46, EPY187, and EPY188. Lane designations in (E) are identical to row designations in (D) and column designations in (F) (**P<0.01).

To provide further evidence that Box1 and Box2 contribute individually to eIF4G1 function, we combined the −ΔB1 or –ΔB2 mutation with the −213 substitution in Box3, which impairs but does not fully inactivate the PABP-binding domain, and thus ‘sensitizes' eIF4G1 to other mutations that reduce eIF4G1•PABP mRNP assembly. Each of the −ΔB1 and −ΔB2 mutations exacerbated the Slg− phenotype conferred by the −459,−213 double mutation (Figure 4D, cf. lanes 3–5), and also the reduction in eIF4G1•PABP mRNP levels produced by the −459,−213 combination (Figure 4E and F, cf. lanes 3–5). Thus, while less critical than Box3, it seems clear that residues in Box1 and Box2 functionally overlap with the canonical PABP-binding domain to promote eIF4G1•PABP mRNP assembly in vivo.

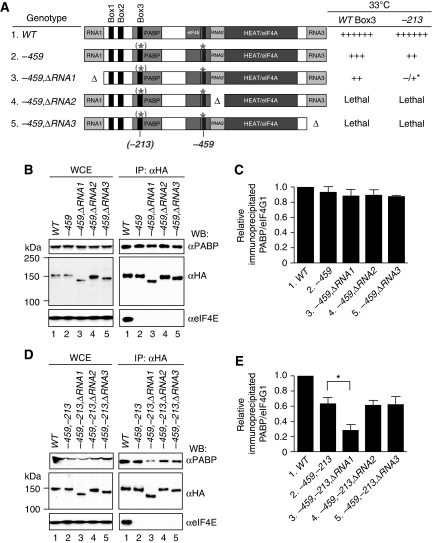

RNA1 and the PABP-binding domain cooperate with the eIF4E-binding domain in eIF4G1 to promote eIF4G1•PABP mRNP assembly in vivo

As noted earlier, simultaneously deleting Box1, Box2, and the entire PABP-binding domain from eIF4G1-459 is not lethal, and additionally removing RNA1 is required to account for the lethality of eliminating residues 1–300 from eIF4G1-459 (Figure 1B). Consistent with the above finding that deleting RNA1 has little effect on growth when combined with only the –459 mutation in the eIF4E-binding site (Figure 1B, rows 3 and 7), the −459,−ΔRNA1 double mutant supports a WT level of eIF4G1•PABP mRNP assembly in the coimmunoprecipitation assay (Figure 5B and C, lanes 2 and 3). By contrast, −ΔRNA1 consistently reduced the eIF4G1•PABP mRNP level below that produced by the −459,−ΔB3ex double mutation when combined with these mutations in the lethal triple mutant (Supplementary Figure S2, lanes 4 and 5). However, because coimmunoprecipitation of PABP is already strongly impaired by the −459,−ΔB3ex double mutation, removing RNA1 in this situation has a relatively small effect on the eIF4G1•PABP mRNP level. Accordingly, we also combined −ΔRNA1 with the −459,−213 double mutation, which, as shown above, maintains a substantial level of eIF4G1•PABP mRNPs. Importantly, −ΔRNA1 clearly reduces the eIF4G1•PABP mRNP level below that given by −459,−213 alone (Figure 5D and E, lanes 2 and 3). The –ΔRNA1 mutation also exacerbates the growth defect conferred by the −459,−213 double mutation (Figure 5A, ‘−213′ column, rows 2 and 3). Thus, simultaneously eliminating RNA1 and impairing the canonical PABP-binding domain in the eIF4G1-459 mutant provokes an additive reduction in eIF4G1•PABP mRNP assembly. The contribution of RNA1 to eIF4G1•PABP mRNP assembly discerned in these experiments helps to account for the lethality of the −459,−ΔRNA1,−ΔB3ex triple mutant.

Figure 5.

The RNA1 domain and canonical PABP-binding domain (Box3ext) in eIF4G1 functionally overlap in promoting cell growth and eIF4G1·PABP mRNP assembly. (A) Growth phenotypes at 33°C for strains of the indicated TIF4631-HA genotypes either lacking (column headed ‘WT Box3') or containing (column headed ‘−213') the −213 mutation. The schematics depict the presence of the relevant deletions or point mutations in eIF4G1, with parenthesis enclosing −213 to signify its presence in only one of the two constructs summarized on each row. The following strains were analysed: row 1, EPY88 and YAS2075; row 2, EPY52 and EPY46; row 3, EPY93 and EPY207. Strains containing constructs in rows 4 and 5 are inviable. (*) The phenotype of the −459,ΔRNA1,−213 triple mutant, shown in the last column of row 3, is unstable and faster growing revertants arise rapidly. (B, C) Coimmunoprecipitation analysis without RNAse treatment for the following strains of indicated TIF4631-HA genotype that also harbour untagged TIF4632: EPY132, EPY133, EPY157, EPY103, and EPY104. (D, E) Coimmunoprecipitation analysis without RNAse treatment for the following strains of indicated TIF4631-HA genotype that also harbour untagged TIF4632: EPY132, EPY203, EPY200, EPY201, and EPY202 (*P<0.05).

RNA-binding domains RNA2 and RNA3 perform important functions downstream of mRNA activation in vivo

eIF4G1 contains two other RNA-binding domains: RNA2, located C-terminal to the eIF4E-binding domain, and RNA3, at the extreme C-terminus (Berset et al, 2003). In contrast to our results with RNA1, deleting either RNA2 or RNA3 from eIF4G1-459 is lethal (Figure 5A), but it does not affect expression of the mutant protein in viable cells coexpressing untagged WT eIF4G2 (Supplementary Figure S1). Interestingly, deletion of neither RNA2 nor RNA3 significantly reduces the yield of eIF4G1•PABP mRNPs formed by eIF4G1-459 in the coimmunoprecipitation assay (Figure 5B and C, lanes 2, 4, and 5). To confirm this conclusion, we combined the −ΔRNA2 or −ΔRNA3 mutation with −459,−213 double mutation, which sensitizes eIF4G1 to other defects in eIF4G1•PABP mRNA assembly. Neither −ΔRNA2 nor −ΔRNA3 further reduced eIF4G1•PABP association relative to that observed for the parental −459,−213 double mutant (Figure 5D and E, lanes 2, 4, and 5). These findings indicate that RNA2 and RNA3 each perform a critical function(s) at a step of initiation subsequent to mRNA activation that apparently cannot be provided by RNA1.

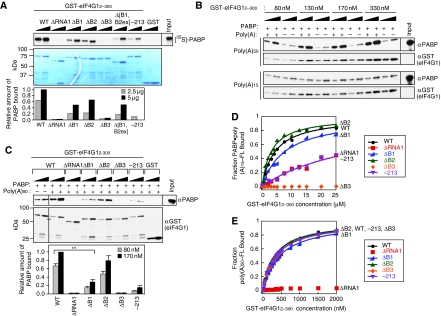

Reconstitution of the contributions of RNA1, Box1, and Box2 to eIF4G1•PABP mRNP formation in vitro

We next sought to reconstitute the effects of mutations in the N-terminus of eIF4G1 on eIF4G1•PABP mRNP assembly in vitro. To this end, we purified recombinant GST fusions from Escherichia coli containing the N-terminal aa 2–300 of WT eIF4G1, or variants lacking functional RNA1, Box1, Box2, or Box3. The fusion proteins were immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads and incubated with [35S]-methionine-labelled PABP synthesized in vitro in nuclease-treated rabbit reticulocyte lysate (RRL). After extensive washing, the bound fraction was eluted, resolved by SDS–PAGE, and visualized by fluorography. As shown in Figure 6A, ∼10% of the input [35S]-PABP bound to WT GST-eIF4G12−300. As expected from previous results (Tarun and Sachs, 1996), this interaction was sensitive to RNAse treatment of the in vitro translated PABP (data not shown), suggesting the formation of GST–eIF4G12−300•PABP mRNPs with both proteins tethered to the same RNA molecules, presumably the PABP mRNA used to program the RRL. As GST–eIF4G12−300 lacks the eIF4E-binding domain, there should be no contribution of eIF4E–eIF4G interaction to the formation of these mRNPs.

Figure 6.

In vitro analysis of the roles of RNA1 and Boxes 1–3 in eIF4G1·PABP mRNP assembly, PABP binding, and RNA binding. (A) RNA1 and Box3 are critically required for RNA-dependent association of recombinant PABP and the eIF4G1 NTD in RRL. Different amounts (2.5 or 5 μg) of WT or mutant GST–eIF4G12–300 fusions immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads were incubated with [35S]-PABP synthesized in RRL. After washes, 50% of bound proteins were resolved by SDS–PAGE and visualized by fluorography (upper panel), together with 10% of the input RRL (rightmost lane). Bound GST–eIF4G12–300 proteins were visualized by Coomassie Blue staining (middle panel). Amounts of bound [35S]-PABP for the indicated mutants relative to WT were calculated and the mean values from two independent experiments are plotted (bottom panel). (B) eIF4G1 NTD–PABP interaction is enhanced by RNA tethering. WT micrococcal nuclease treated, immobilized GST–eIF4G12–300 (from 80 to 330 nM) was incubated with micrococcal nuclease treated, purified PABP (at 66 nM) in the presence or absence of 1 μM poly(A)50 or poly(A)15 RNA. After washing the beads, 1 and 2% of bound proteins (loaded in adjacent lanes headed by black wedges) were subjected to western analysis with antibodies against PABP or GST, and 0.2% of the input PABP was loaded in the rightmost lane. (C) RNA1, Box1, and Box3 are required to form GST–eIF4G12–300–PABP complexes tethered to poly(A)50. Micrococcal nuclease treated, immobilized WT or mutant GST–eIF4G12–300 proteins were incubated at 80 or 170 nM with purified PABP and poly(A)50, as in (B). Western signals were quantified and amounts of bound PABP for the indicated mutants relative to WT were calculated from four independent experiments. Mean ratios±s.e.m. are plotted in the bottom panel (**P<0.01). (D) Both RNA1 and Box3 are required for direct PABP binding to the eIF4G1 NTD. poly(A)15–FL (30 nM) was pre-bound to PABP (500 nM) and incubated with different concentrations of the indicated GST–eIF4G12–300 proteins, and the increase in fluorescence anisotropy of poly(A)15–FL was measured. Each point is the average of four to seven independent experiments. Kd values derived from the data are given in column 2 of Table I. (E) RNA1 is required for poly(A)50–FL binding to the eIF4G1 NTD. Binding of poly(A)50–FL (30 nM) to the indicated GST–eIF4G12–300 proteins was measured as in (D). Each point is the average of at least three independent experiments. Kd values derived from the data are given in column 3 of Table I.

Applying this assay to the mutant GST–eIF4G12−300 proteins, we found that eliminating RNA1 or Box3 from GST–eIF4G12−300 essentially abolished formation of the GST–eIF4G12−300•PABP complexes, whereas the −213 substitution or eliminating Box1 or Box2 substantially reduced, but did not abolish, complex formation (Figure 6A). The fact that eliminating Box3 has a stronger effect than does eliminating Box1, Box2, or the −213 substitution is consistent with the results of our coimmunoprecipitation analysis of native eIF4G1•PABP complexes shown above. The effect of eliminating RNA1 differs between the two assays, however, abolishing GST–eIF4G12−300–PABP interaction in vitro but having no effect on PABP's association with the eIF4G-459 mutant in yeast WCEs (Figure 5B and C). One possibility to explain this discrepancy is that RNA2 or RNA3 (lacking in GST–eIF4G12−300) might substitute for the RNA-binding function of RNA1 in full-length eIF4G1, even though RNA1 cannot perform the putative post-assembly function(s) of RNA2 or RNA3 deduced above.

To rule out possible contributions of other proteins in the RRL to complex formation between GST–eIF4G12−300 and PABP, we conducted binding assays with purified recombinant PABP. Additionally, we employed two different RNAs in the binding reactions: a poly(A) 50-mer and a poly(A) 15-mer. With increasing concentrations of the WT GST–eIF4G12−300 fusion protein, we observed dose-dependent recovery of PABP in the bound fraction in the presence of poly(A)50 (Figure 6B, the two upper panels). By contrast, low-level constitutive recovery of PABP was seen in the presence or absence of poly(A)15 (Figure 6B, lower panels). These findings suggest that PABP binding to eIF4G12−300 at these concentrations (66 nM PABP and ⩽330 nM GST–eIF4G12−300) is dependent on tethering of these proteins to the same poly(A)50 molecules, which cannot occur with the shorter poly(A)15 molecules. This conclusion fits with the fact that PABP has a binding site of 12 A nucleotides (Sachs et al, 1987), and with the results below indicating that direct PABP–GST–eIF4G12−300 interaction occurs with a Kd of ≈4 μM.

Using poly(A)50 in the tethering assay with purified PABP and GST–eIF4G12−300, we obtained results similar in most respects to those in Figure 6A obtained using PABP translated in the RRL. Thus, eliminating RNA1 or Box3 essentially abolishes formation of the GST–eIF4G12−300•PABP•poly(A)50 RNP, whereas both the −213 substitution and eliminating Box1 produce significant, but less severe, reductions in RNP formation (Figure 6C). However, we did not observe a significant effect of –ΔB2 in this more defined assay.

We wished to determine whether the RNA1 and Box1 regions in eIF4G1 contribute to direct PABP–eIF4G interaction. To this end, we used fluorescently labelled poly(A)15 and measured the increase in fluorescence anisotropy of the pre-formed PABP–poly(A)15 complex as a function of increasing amounts of GST–eIF4G12−300 (Figure 6D). As poly(A)15 is too small to permit tethering of GST–eIF4G12−300 to the PABP•poly(A)15 complex (Figure 6B), it serves only as the fluorescent ‘tag' on PABP in these binding assays. The anisotropy measurements revealed a Kd of 4.0 μM for the GST–eIF4G12−300•PABP•poly(A)15 complex (Table I, column 2), fairly similar to that reported previously (27 μM) for binding of the N-terminal region of human PABP to the PABP-binding segment of human eIF4GI (Groft and Burley, 2002). Analysis of the GST–eIF4G12−300 mutants in this assay revealed that, as might be expected, eliminating Box3 abolished interaction, whereas the −213 substitution produced an ∼10-fold reduction in binding affinity (Figure 6D; Table I, column 2). Interestingly, removing RNA1 impaired binding to the same extent as –213, indicating a significant role for this region in PABP binding by eIF4G1. ΔB1 produced a modest, but statistically significant, two-fold increase in Kd, whereas ΔB2 had no effect on the PABP–eIF4G12−300 interaction. The Box3ext segment, lacking RNA1, Box1, and Box2, bound to PABP–poly(A)15 with the same affinity as did the ΔRNA1 fragment (Table I, column 2). We interpret these findings to indicate that RNA1 and Box1 make substantial and modest contributions, respectively, to the direct interaction of PABP with the Box3ext region of the eIF4G1 NTD.

Table 1. Affinities of mutant and WT GST-eIF4G12–300 proteins for PABP and poly(A)50.

| GST-eIF4G12−300 construct | Dissociation constants (Kd) | |

|---|---|---|

| GST-eIF4G12–300· PABP–poly(A)15−FLa (μM) | GST-eIF4G12–300· poly(A)50−FLb (nM) | |

| WT | 4.0±0.6 | 330±36 |

| ΔRNA1 | 33±6.5** | NBc |

| ΔB1 | 8.0±0.9** | 455±22* |

| ΔB2 | 3.4±0.9 | 324±35 |

| ΔB3 | NBc | 371±11 |

| −213 | 36±3.6** | 361±10 |

| Δ[B1,B2ex] | 8.9d | 437±30 |

| Box3ext (Δ1–187) | 36±2.3** | NBc |

| Values are the averages of four to seven (a) or at least three (b) independent experiments. Errors denote the standard errors of the mean (s.e.m.). | ||

| cNo binding was detectable. | ||

| dThis value is the average of two independent experiments. | ||

| Statistical significance of the differences between mutant and WT were assessed using an unpaired Student's t-test (*P<0.05; **P<0.01). | ||

Finally, we analysed the effects of these mutations on RNA-binding activity by measuring the increase in anisotropy of fluorescently labelled poly(A)50 on binding to GST–eIF4G12−300 or its mutant derivatives (in the absence of PABP) (Figure 6E; Table I, column 3). The Kd obtained from this assay for WT GST–eIF4G12−300, 330 nM, is considerably smaller than that found previously for the isolated RNA1 fragment (5 μM) using a filter-binding assay and a 38-nt A-rich single-stranded RNA (Berset et al, 2003). As might be expected, elimination of RNA1 abolished detectable binding of poly(A)50 in this assay, whereas ΔB3 and –213 had no effect on binding (Table I, column 3). Eliminating Box1 alone produced a small, but statistically significant increase in Kd, suggesting that the Box1 region slightly enhances the RNA-binding activity of the RNA1 segment of the eIF4G1 NTD.

Interestingly, we found that elimination of Box1, either alone or together with Box2, completely abolished RNA binding to GST–eIF4G12−300 in an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) using a radiolabelled 43-nt RNA as ligand (Supplementary Figure S3). As expected, the ΔRNA1 mutation also abolished RNA binding in this EMSA experiment. By contrast, eliminating Box2 or Box3 moderately reduced RNA binding, and the –213 mutation had no effect on the interaction (Supplementary Figure S3). One possibility to account for the much stronger effect of ΔB1 in the EMSA assay compared with the anisotropy-binding assay (Table I) is to propose that Box1 interacts with, or affects the conformation of, the RNA1 region, such that eliminating Box1 opens up the structure of the RNA•eIF4G12−300 complex in a way that increases both the association and the dissociation rates for RNA by similar amounts. This would produce only a small change in Kd but could dramatically lower the yield of RNA•eIF4G12−300 complexes in the non-equilibrium conditions of the EMSA assay. In any event, we conclude that RNA1 provides the principal RNA-binding activity of the eIF4G1 NTD and that Box1 makes a supporting contribution to this activity.

Discussion

In this report, we have dissected the contributions of different segments of the eIF4G1 NTD and its three RNA-binding domains to the function of eIF4G1 in forming activated eIF4G•PABP mRNPs. Previous results led to the conclusion that the PABP-binding domain of eIF4G1, between aa 188–299, is dispensable for normal growth at 30°C, but is essential when eIF4G1 harbours the −459 mutation that disrupts eIF4E–eIF4G1 association (Tarun and Sachs, 1997). We found that this is not the case, however, and that additionally removing the NTD RNA1 (aa 1–82) is required to recapitulate the lethality of removing residues 1–300 from the eIF4G1-459 protein. We also provided evidence that eliminating RNA1 decreases the abundance of native eIF4G1•PABP mRNPs present in cell extracts when both PABP and eIF4E interactions with eIF4G1 are compromised. The role of RNA1 in stimulating eIF4G1•PABP RNP complexes was reconstituted in vitro using a GST–eIF4G1 NTD fusion and recombinant PABP. At low concentrations of these proteins, it appeared that complex formation required RNAs long enough to permit binding of GST–eIF4G12−300 and PABP to the same molecules. Both RNA1 and the canonical PABP-binding domain (Box3) were essential for PABP association with GST–eIF4G12−300 in these tethering assays.

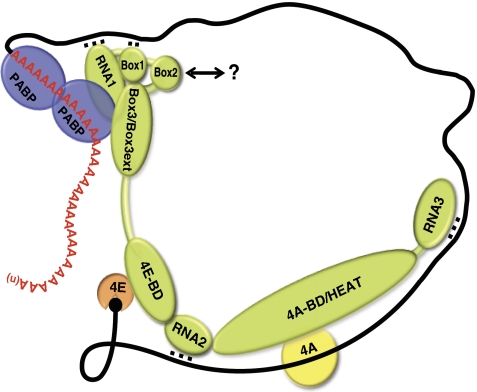

By measuring RNA-independent binding of PABP to GST–eIF4G12−300 (at much higher protein concentrations), we found that eliminating Box3 abolished direct interaction between PABP and GST–eIF4G12−300. As eliminating Box3 does not affect RNA binding by GST–eIF4G12−300, we conclude that Box3 stabilizes eIF4G12−300–PABP mRNPs solely by providing a direct contact with PABP. As expected, removing RNA1 eliminated the RNA-binding activity of GST–eIF4G12−300, but, interestingly, it also significantly reduced direct (non-tethered) binding of PABP to GST–eIF4G12−300. The role of RNA1 in facilitating eIF4G1–PABP interaction could be indirect; for example, RNA1 might associate with the Box3 region and allosterically stimulate its binding to PABP (Figure 7). Alternatively, RNA1 could provide an auxiliary PABP-binding site of lower affinity, which is insufficient on its own for detectable GST–eIF4G12−300–PABP interaction in vitro and for assembly of native eIF4G1•PABP mRNPs. In any event, our results suggest that RNA1 stabilizes eIF4G1•PABP mRNPs both by enhancing eIF4G1 interaction with PABP and by enabling direct binding of the eIF4G1 NTD to mRNA (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Model depicting the functions of multiple elements in the eIF4G1 NTD in promoting interactions with mRNA or PABP to enhance assembly of the closed-loop eIF4F mRNP. The ability of RNA1 to enhance direct binding of the eIF4G1 NTD to PABP, promoting mRNA circularization, could result from direct binding of RNA1 to PABP or through interaction of RNA1 with the canonical PABP-binding domain in eIF4G1 (containing Box3), allosterically stimulating PABP binding. RNA1 also interacts directly with the mRNA, and Box1 directly or indirectly enhances this interaction. Box2 may recruit another unknown factor (?) that promotes eIF4F mRNP assembly. RNA2 and RNA3 might also contact mRNA (as depicted) and help to stabilize the eIF4F·mRNP, but each of them has another critical function downstream in the pathway, possibly 43S PIC attachment or ribosomal scanning. 4E-BD, eIF4E-binding domain; 4A-BD, eIF4A-binding domain.

We found that the region between RNA1 and the canonical PABP-binding domain in eIF4G1 contains two additional segments conserved among eIF4G proteins from different Saccharomyces species, Box1 and Box2, which also contribute to eIF4G1•PABP mRNP formation in vivo. This conclusion arises most clearly from the fact that eliminating Box1 or Box2 exacerbates both the Slg− phenotype and defect in eIF4G1•PABP mRNP formation of the eIF4G1-459,−213 mutant. A contribution of Box1 in forming eIF4G12−300•PABP mRNPs was also observed in vitro, and Box1 makes a moderate contribution to both direct PABP binding and RNA binding by the eIF4G1 NTD. These activities might well account for the reductions in eIF4G1•PABP mRNP levels and cell growth that result when Box1 is eliminated from the eIF4G1-459,−213 mutant. Alternatively, Box1 could provide a binding site for another factor, for example eIF4B or the DEAD-box helicase Ded1, that promotes eIF4G1•mRNA•PABP assembly or stability in vivo. This last explanation could also be invoked to account for the stimulatory effect of Box2 on eIF4G1•PABP mRNP assembly in vivo, because eliminating Box2 from GST–eIF4G12−300 had no effect on direct PABP or RNA binding in vitro.

Combining all of our findings on the effects of mutating different segments in the eIF4G1 NTD on cell growth and interactions of eIF4G with PABP and RNA, we propose that activation of mRNA by eIF4F involves redundant interactions of eIF4G1 with the eIF4E/cap and PABP/polyA tail and also direct binding of eIF4G1 to mRNA (Figure 7). Multiple elements in the eIF4G1 NTD contribute to the strength of PABP–eIF4G1 and mRNA–eIF4G1 interactions, with the canonical PABP-binding domain (Box3) and RNA1 contributing the most to the direct interactions with PABP and mRNA, respectively. RNA1 also significantly stimulates direct PABP–eIF4G interaction, and Box1 and Box2 promote eIF4G interactions with PABP or mRNA, possibly by interacting with the Box3 or RNA1 domain to promote ligand binding by these segments, or by recruiting other factors that promote eIF4F•mRNA interaction.

Interestingly, a sequence alignment of eIF4G proteins that includes additional fungal species and mammalian eIF4GI reveals that the Box2 region is more highly conserved than Box3 (Supplementary Figure S4). This alignment also shows an overlap between Box2 and the PABP-binding segment in human eIF4GI (KRERKTIRIRD--PNQG------GKDITEEIMSG) (Groft and Burley, 2002), which is unrelated to the canonical PABP-binding element (Box3) in yeast eIF4G proteins. Box3 also shows no obvious relationship to the PABP-binding motifs PAM1 and PAM2 identified in other mammalian PABP-binding proteins (Khaleghpour et al, 2001). Thus, it appears that different segments of the NTD have evolved to mediate tight PABP binding in yeast versus mammalian eIF4G proteins. Burley and colleagues showed that the N-terminal region of mammalian PABP (aa 1–190) can interact with the PABP-binding domain in eIF4GI (aa 132–160) in the absence of poly(A) with a Kd of 27 μM (Groft and Burley, 2002). We measured a Kd of 4.0 μM for direct binding of full-length yeast PABP to the entire eIF4G1 NTD. Perhaps, the tighter interaction observed here reflects the contributions (direct or indirect) of RNA1 or Box1/Box2 to PABP binding by yeast eIF4G1. Interestingly, a fragment of human eIF4GI of aa 45–160 was found to bind PABP more tightly than does a smaller fragment (aa 132–160) containing only the minimal PABP-binding motif (Imataka et al, 1998; Groft and Burley, 2002), which might indicate contributions to PABP binding from multiple segments in the human eIF4GI NTD as well.

In the course of reconstituting GST–eIF4G12−300•PABP mRNPs from purified proteins, we observed that poly(A)50, but not poly(A)15, can support PABP binding to GST–eIF4G12−300 at poly(A) concentrations where the PABP should be saturated with poly(A) (Deardorff and Sachs, 1997). The inactivity of poly(A)15 in this assay implies that poly(A) does not allosterically activate PABP for binding to eIF4G1 NTD at submicromolar concentrations of these proteins in the manner suggested previously (Tarun and Sachs, 1996). Our results are consistent with the avidity model proposed for PABP–eIF4G interaction, in which longer poly(A) tails increase the local concentration of PABP molecules and allow for greater binding to eIF4G despite high association and dissociation rates (Groft and Burley, 2002). However, it is also possible, as we suggested above, that poly(A)50 is simply long enough to allow simultaneous, cooperative binding of PABP and the eIF4G1 NTD to one another and to the same RNA molecule.

Our results also provide new insights into the functions of the other two RNA-binding domains in eIF4G1. We found that eliminating either RNA2 or RNA3 is lethal in combination with the –459 mutation. Given that eliminating RNA1 or the canonical PABP-binding segment (with –ΔB3ex) does not even exacerbate the Slg− phenotype of the −459 mutant at 30°C, it seems clear that RNA2 and RNA3 are more critical than any of the elements in the eIF4G1 NTD when eIF4E binding to eIF4G1 is impaired. Indeed, eliminating RNA3 confers a marked Slg− phenotype even with no other mutations present in eIF4G1 (Supplementary Table S1). Our finding that eliminating RNA2 or RNA3 does not provoke any further reduction in the amount of PABP coimmunoprecipitating with eIF4G1-459,–213 strongly suggests that eliminating RNA2 or RNA3 impairs a critical step of initiation downstream of eIF4G1•PABP mRNP formation. This conclusion would not contradict the above suggestion that RNA2 or RNA3 can substitute for the mRNA-binding function of RNA1 during mRNA activation if we stipulate that RNA2 and RNA3 participate in multiple steps of the initiation pathway involving RNA interactions with eIF4G1.

RNA2 or RNA3 might contribute to the function of eIF4G1 in recruitment of the 43S PIC to the mRNA, or they could stimulate ribosomal scanning. The central region of mammalian eIF4G1 has been implicated in ribosomal scanning in several studies (Pestova and Kolupaeva, 2002; Prevot et al, 2003; Poyry et al, 2004), but it is unclear whether RNA binding by this region of eIF4GI contributes to this function. On the other hand, Yanagiya et al (2009) presented evidence that recombinant eIFGI fragments containing the central region of eIF4GI and exhibiting RNA-binding activity, or a heterologous RNA-binding domain fused to eIF4GI fragments, enhance eIF4F binding to the cap structure of mRNA in vitro, and thus appear to promote mRNA activation. Additional experiments will be required to determine whether RNA2 and RNA3 in yeast eIF4G1 enhance 43S PIC binding to mRNA or subsequent ribosomal scanning. Either possibility would be consistent with our finding that deleting RNA2 or RNA3 is lethal in the presence of the −459 mutation, as the cap–eIF4E interaction with eIF4G1 could be critical for directing attachment of the 43S PIC to the 5′ end of the mRNA and establishing 5′ to 3′ directional scanning for selection of 5′-proximal AUG codons.

Simultaneous deletion of RNA1, Box1, Box2, and the canonical PABP-binding domain in eIF4G1 by the ΔN300 mutation from otherwise WT eIF4G1 has a much less severe phenotype than does the –459 single mutation (Tarun and Sachs, 1997) (Figure 1B, rows 2 and 3). This finding indicates that the eIF4E–eIF4G1 interaction, together with possible contributions from RNA2, RNA3, and other C-terminal regions in eIF4G1, suffices for efficient assembly of eIF4F•mRNA complexes when both PABP and mRNA interactions with the eIF4G1 NTD are absent. Even when eIF4E–eIF4G1 association is impaired by the −459 substitution, and when the Box1–Box2 region is also missing, the canonical PABP-binding domain is dispensable for translation as long as RNA1 is still intact. These findings indicate that closed-loop formation via PABP–eIF4G interaction is not essential in vivo.

Association of RNA1 with the mRNA in conjunction with cap/eIF4E–eIF4G interaction could mediate mRNA loop formation, but by interacting with different segments in the mRNA, a lariat of variable loop size would be produced, rather than a circle with poly(A) tail and cap in proximity. This prediction assumes that RNA1 does not share with PABP a strong preference for poly(A), which we confirmed by anisotropy-binding assays showing that the affinity of the eIF4G NTD for the 43-nt UC-rich mRNA used in Supplementary Figure S3 is actually somewhat greater than for poly(A)50 (data not shown). We cannot exclude that a closed-loop mRNP can still be formed by eIF4G1 mutants that lack the PABP-binding domain through an unknown mechanism. However, there is a strong possibility that a closed-loop per se is not fundamentally important for translation initiation, and that PABP–eIF4G1 association serves primarily as one of several redundant interactions that stabilize eIF4G binding to mRNA—which is a key event for efficient recruitment of the 43S PIC and ribosomal scanning. Indeed, PABP, but not eIF4G, is dispensable for translation initiation on native mRNAs in reconstituted systems (Pestova and Kolupaeva, 2002; Mitchell et al, 2010), and also in reticulocyte lysates unless supplemented with a non-specific RNA-binding protein like YB-1. It is thought that by stabilizing eIF4F•mRNA association through its simultaneous interaction with eIF4G and the poly(A) tail, PABP can overcome the ability of YB-1 and other RNA-binding proteins to compete with eIF4F for mRNA binding (Svitkin et al, 2009). Our results imply that this proposed function for PABP, dependent on the Box3 region, is also dispensable in vivo unless both eIF4E- and mRNA-binding activities of eIF4G1 are compromised. Although the genetic findings in yeast indicate that mRNA circularization is not essential for translation, they do not exclude the possibility that it enhances some aspect of initiation, or that closed-loop formation facilitates the functions of regulatory proteins or miRNAs that bind to the 3′UTR and target interactions of eIF4G with eIF4E or the 43S PIC (Sonenberg and Hinnebusch, 2007).

Materials and methods

Plasmids and yeast strains

All plasmids employed in this study are listed in Table II and details of their construction are provided in the Supplementary data. All yeast strains employed are listed in Table III. Strains YAS2282, −2069, −2075, −2070, −2104, and −2071 were purchased from the ATCC (Manassas, VA). All novel strains in Table III were constructed by introducing a TRP1 CEN4 plasmid with the appropriate TIF4631-HA allele into YAS2282. The resulting transformants were replica plated on 5-fluoroorotic acid plates lacking tryptophan (FOA-Trp) and incubated at 30°C to evict the resident URA3 plasmid containing WT TIF4632 (Guthrie and Fink, 1991; Tarun and Sachs, 1997). No visible growth on FOA-Trp plates after 5 to 7 days indicated a lethal phenotype.

Table 2. Plasmids used in this study.

| Yeast plasmid | Relevant feature | Source |

|---|---|---|

| pBAS2004 | TIF4632 URA3 CEN4 | Tarun and Sachs (1996) |

| pBAS2078 | TIF4631 TRP1 CEN4 | Tarun and Sachs (1997) |

| pBAS3157 | TIF4631-HA TRP1 CEN4 | Tarun and Sachs (1997) |

| pEP88 | TIF4631-HA-Bam TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP206 | tif4631-HA-Bam-Δ1–300 TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pBAS3158 | tif4631-HA-459 TRP1 CEN4 | Tarun and Sachs (1997) |

| pEP112 | tif4631-HA-Bam-459,Δ197–224 TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP87 | tif4631-HA-Bam-459,Δ94–187 TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP86 | tif4631-HA-Bam-459,Δ94–300 TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP82 | tif4631-HA-459,Δ188–300 TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP46 | tif4631-HA-213,–459 TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP130 | tif4631-HA-Bam-459,Δ94–111 TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP131 | tif4631-HA-Bam-459,Δ128–150 TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pBAS3120 | tif4631–213 TRP1 CEN4 | Tarun and Sachs (1997) |

| pEP187 | tif4631-HA-Bam-213,–459,Δ94–111 TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP188 | tif4631-HA-Bam-213,–459,Δ128–150 TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP93 | tif4631-HA-Bam-459,Δ1–82 TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP205 | tif4631-HA-Bam-459,Δ1–300 TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP102 | tif4631-HA-Bam-459,Δ1–82,Δ188–300 TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP103 | tif4631-HA-Bam-459,Δ492–539 TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP104 | tif4631-HA-459,Δ883–952 TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP177 | tif4631-HA-Bam-Δ1–82 TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP58 | tif4631-Δ1–187 TRP1 CEN4 | Tarun et al (1997) |

| pEP113 | tif4631-HA-Bam-Δ492–539 TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP199 | tif4631-HA-Δ883–952 TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP148 | tif4631-HA-Bam-459,Δ1–187 TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP207 | tif4631-HA-Bam-213,–459,Δ1–82 TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP201 | tif4631-HA-Bam-213,–459,Δ492–539 TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP202 | tif4631-HA-213,–459,Δ883–952 TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP115 | tif4631-HA-Bam-459,Δ1–82,Δ197–224 TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP59a | tif4631–459,Δ1–187 TRP1 CEN4 | Tarun et al (1997) |

| pEP60b | tif4631-Δ1–300 TRP1 CEN4 | Tarun et al (1997) |

| pEPB1c | PT7lac-GST-TIF46312–300-His6 PT7lac-CDC33 | This study |

| pEPB6c | PT7lac-GST-tif46312–300-Δ1–82 (RNA1)-His6 PT7lac-CDC33 | This study |

| pEPB7c | PT7lac-GST-tif46312–300-Δ94–111 (ΔB1)-His6 PT7lac-CDC33 | This study |

| pEPB8c | PT7lac-GST-tif46312–300-Δ128–150 (ΔB2)-His6 PT7lac-CDC33 | This study |

| pEPB9c | PT7lac-GST-tif46312–300-Δ197–224 (ΔB3)-His6 PT7lac-CDC33 | This study |

| pEPB10c | PT7lac-GST-tif46312–300-Δ94–187 (Δ[B1,B2ex])-His6 PT7lac-CDC33 | This study |

| pEPB11c | PT7lac-GST-tif46312–300–213-His6 PT7lac-CDC33 | This study |

| pEPB12c | PT7lac-GST-tif46312–300-Δ1–187-His6 PT7lac-CDC33 | This study |

| aThis plasmid was rescued from yeast strain YAS2104 (Tarun et al, 1997). | ||

| bThis plasmid was rescued from yeast strain YAS2071 (Tarun et al, 1997). | ||

| cThe different TIF4631 fragments were inserted at the BamHI and HindIII sites of pEPB1. Bacterial strain BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIL was transformed with the indicated plasmids. | ||

Table 3. S. cerevisiae strains used in this study.

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| YAS2282 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg | Tarun and Sachs (1997) |

| tif4632∷ura3 pBAS2004 [pTIF4632 URA3 CEN4] | ||

| YAS2069 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷LEU2 | Tarun and Sachs (1997) |

| tif4632∷ura3 pBAS2078 [pTIF4631 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| EPY88 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg | This study |

| tif4632∷ura3 pEP88 [TIF4631-HA-Bam TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| EPY206 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg | This study |

| tif4632∷ura3 pEP206 [tif4631-HA-Bam-Δ1–300 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| EPY52a | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg | Tarun and Sachs (1997) |

| tif4632∷ura3 pBAS3158 [tif4631-HA-459 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| EPY112 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg | This study |

| tif4632∷ura3 pEP112 [tif4631-HA-Bam-459,Δ197–224 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| EPY87 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg | This study |

| tif4632∷ura3 pEP87 [tif4631-HA-Bam-459,Δ94–187 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| EPY86 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg | This study |

| tif4632∷ura3 pEP86 [tif4631-HA-Bam-459,Δ94–300 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| EPY82 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg | This study |

| tif4632∷ura3 pEP82 [tif4631-HA-459,Δ188–300 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| EPY46 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg | This study |

| tif4632∷ura3 pEP46 [tif4631-HA-213,–459 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| EPY130 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg | This study |

| tif4632∷ura3 pEP130 [tif4631-HA-Bam-459,Δ94–111 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| EPY131 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg | This study |

| tif4632∷ura3 pEP131 [tif4631-HA-Bam-459,Δ128–150 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| YAS2075 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷LEU2 | Tarun and Sachs (1997) |

| tif4632∷ura3 pBAS3120 [tif4631–213 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| EPY187 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg | This study |

| tif4632∷ura3 pEP187 [tif4631-HA-Bam-213,–459,Δ94–111 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| EPY188 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg | This study |

| tif4632∷ura3 pEP188 [tif4631-HA-Bam-213,–459,Δ128–150 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| EPY93 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg | This study |

| tif4632∷ura3 pEP93 [tif4631-HA-Bam-459,Δ1–82 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| EPY132 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg | This study |

| tif4632::ura3 pEP88 [TIF4631-HA-Bam TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| pBAS2004 [pTIF4632 URA3 CEN4] | ||

| EPY133 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg | This study |

| tif4632∷ura3 pBAS3158 [tif4631-HA-459 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| pBAS2004 [pTIF4632 URA3 CEN4] | ||

| EPY205 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg | This study |

| tif4632∷ura3 pEP205 [tif4631-HA-Bam-459,Δ1–300 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| pBAS2004 [pTIF4632 URA3 CEN4] | ||

| EPY157 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg tif4632∷ura3 | This study |

| pEP93 [tif4631-HA-Bam-459,Δ1–82 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| pBAS2004 [pTIF4632 URA3 CEN4] | ||

| EPY158 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg tif4632∷ura3 | This study |

| pEP82 [tif4631-HA-459,Δ188–300 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| pBAS2004 [pTIF4632 URA3 CEN4] | ||

| EPY102 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg tif4632∷ura3 | This study |

| pEP102 [tif4631-HA-Bam-459,Δ1–82,Δ188–300 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| pBAS2004 [pTIF4632 URA3 CEN4] | ||

| EPY103 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg tif4632∷ura3 | This study |

| pEP103 [tif4631-HA-Bam-459,Δ492–539 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| pBAS2004 [pTIF4632 URA3 CEN4] | ||

| EPY104 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg tif4632∷ura3 | This study |

| pEP104 [tif4631-HA-459,Δ883–952 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| pBAS2004 [pTIF4632 URA3 CEN4] | ||

| EPY161b | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg | Tarun and Sachs (1997) |

| tif4632∷ura3 pBAS2004 [pTIF4632 URA3 CEN4] | ||

| pBAS2078 [pTIF4631 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| EPY203 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg tif4632∷ura3 | This study |

| pEP46 [tif4631-HA-213,–459 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| pBAS2004 [pTIF4632 URA3 CEN4] | ||

| EPY200 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg tif4632∷ura3 | This study |

| pEP207 [tif4631-HA-Bam-213,–459,Δ1–82 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| pBAS2004 [pTIF4632 URA3 CEN4] | ||

| EPY201 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg tif4632∷ura3 | This study |

| pEP201 [tif4631-HA-Bam-213,–459,Δ492–539 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| pBAS2004 [pTIF4632 URA3 CEN4] | ||

| EPY202 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 | This study |

| pEP202 [tif4631-HA-213,–459,Δ883–952 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| pBAS2004 [pTIF4632 URA3 CEN4] | ||

| EPY177 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg | This study |

| tif4632∷ura3 pEP177 [tif4631-HA-Bam-Δ1–82 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| EPY58c | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg | |

| tif4632::ura3 pEP58 [tif4631-Δ1–187 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| EPY113 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg tif4632∷ura3 | This study |

| pEP113 [tif4631-HA-Bam-Δ492–539 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| EPY199 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632∷ura3 | This study |

| pEP199 [tif4631-HA-Δ883–952 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| EPY148 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg | This study |

| tif4632∷ura3 pEP148 [tif4631-HA-Bam-459,Δ1–187 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| EPY207 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg tif4632∷ura3 | This study |

| pEP207 [tif4631-HA-Bam-213,–459,Δ1–82 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| EPY115 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4∷HIS3 tif4631∷leu2hisg tif4632∷ura3 | This study |

| pEP115 [tif4631-HA-Bam-459,Δ1–82,Δ197–224 TRP1 CEN4] | ||

| aThe plasmid pBAS3158 was transformed into yeast strain YAS2282.Transformants were plated on 5-fluoroorotic acid plates lacking tryptophan (FOA-W) to eliminate the plasmid expressing wild-type TIF4632. | ||

| bThe plasmid pBAS2078 was transformed into yeast strain YAS2282. | ||

| cThe plasmid pEP58 was rescued from yeast strain YAS2070 (Tarun et al, 1997) and transformed into yeast strain YAS2282.Transformants were plated on FOA-W plates to eliminate the plasmid expressing wild-type TIF4632. | ||

Coimmunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis

Yeast strains were grown in 100 ml of SC-Trp, or SC-Trp also lacking uracil (SC-Ura,-Trp), to an A600 of 0.5–0.8, and WCEs were prepared as described in the Supplementary data. For coimmunoprecipitation, 0.5–2 mg of WCEs was diluted with lysis buffer to 500 μl and incubated with 12.5 μg of agarose-conjugated anti-HA antibodies overnight at 4°C with rocking. Immune complexes captured on agarose beads were collected by centrifugation, washed five times with 500 μl of lysis buffer (−protease inhibitors) containing 0.015 % SDS (w/v), and resuspended in 45–60 μl of 2 × Laemmli sample buffer. After boiling for 5 min, samples were resolved by 4–20% SDS–PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, and probed with appropriate antibodies. Immune complexes were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For western blot analysis of WCEs, extracts were prepared by trichloroacetic acid extraction, as previously described (Reid and Schatz, 1982). The sources of antibodies are provided in the Supplementary data.

GST–eIFG12−300 pulldowns of PABP

Reactions with [35S]-PABP in RRL: [35S]-PABP was synthesized in the presence of [35S]methionine using the TNT Quick Coupled Transcription/Translation RRL kit (Promega), according to the manufacturer's instructions, partially purified by ammonium sulphate precipitation (Qiu et al, 1998), and resuspended in 50 μl of Buffer AG (20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 12.5 % glycerol). GST–eIF4G12−300 fusions were expressed in E. coli and purified as described in the Supplementary data. Purified GST fusion proteins were immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (GE Healthcare), treated with RNase T1 (6795 U, Sigma) at 26°C for 30 min, washed four times with PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100, and resuspended in 240 μl of Buffer AT (20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.1% Triton X-100). Ten microliters of [35S]-PABP was mixed with the beads and incubated at 4°C for 2 h with rocking. Beads were washed five times with 1 ml of Buffer AT, resuspended in 25 μl of 2 × Laemmli sample buffer, and separated by SDS–PAGE. Gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue, fixed with destaining solution (50% methanol, 10% glacial acetic acid), treated with En3HanceTM Autoradiography Enhancer (Perkin-Elmer), dried, and subjected to fluorography at −70°C.

Reactions with purified PABP: Recombinant, micrococcal nuclease-treated PABP (1.1 μg), purified as described in the Supplementary data, was incubated on ice for 30 min with poly(A)50 or poly(A)15 RNA (1 μM; Thermo Scientific), and then mixed with micrococcal nuclease-treated GST–eIF4G12−300 fragments immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads in a final volume of 250 μl of Buffer AT. After 2 h at 4°C, beads were washed three times with Buffer AT, resuspended in 200 μl of 2 × Laemmli loading buffer, and analysed by western blot analysis.

Fluorescence anisotropy assays

Assays were performed as described previously with minor modifications (Maag and Lorsch, 2003; Nanda et al, 2009), as described in the Supplementary data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Alan Sachs, John McCarthy, and Jon Warner for generous gifts of strains, plasmids, or antibodies, and Byung-Sik Shin for excellent technical advice. This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, an NIH grant to JRL (GM62128), and an American Heart Association award (SEW).

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Altmann M, Sonenberg N, Trachsel H (1989) Translation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: initiation factor 4E-dependent cell-free system. Mol Cell Biol 9: 4467–4472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amrani N, Ghosh S, Mangus DA, Jacobson A (2008) Translation factors promote the formation of two states of the closed-loop mRNP. Nature 453: 1276–1280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berset C, Zurbriggen A, Djafarzadeh S, Altmann M, Trachsel H (2003) RNA-binding activity of translation initiation factor eIF4G1 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. RNA 9: 871–880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson BK, Gilbert WV, Doudna JA (2010) Functional overlap between eIF4G isoforms in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS One 5: e9114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Cruz J, Iost I, Kressler D, Linder P (1997) The p20 and Ded1 proteins have antagonistic roles in eIF4E-dependent translation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 5201–5206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff JA, Sachs AB (1997) Differential effects of aromatic and charged residue substitutions in the RNA binding domains of the yeast poly(A)-binding protein. J Mol Biol 269: 67–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez D, Altmann M, Benz J, Baumann U, Trachsel H (1999) Interaction of translation initiation factor eIF4G with eIF4A in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 274: 26720–26726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaemmaghami S, Huh WK, Bower K, Howson RW, Belle A, Dephoure N, O'Shea EK, Weissman JS (2003) Global analysis of protein expression in yeast. Nature 425: 737–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyer C, Altmann M, Lee HS, Blanc A, Deshmukh M, Woolford JL, Trachsel H, Sonenberg N (1993) TIF4631 and TIF4632: Two yeast genes encoding the high-molecular-weight subunits of the cap-binding protein complex (eukaryotic initiation factor 4F) contain an RNA recognition motif-like sequence and carry out an essential function. Mol Cell Biol 13: 4860–4874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyer C, Altmann M, Trachsel H, Sonenberg N (1989) Identification and characterization of cap binding proteins from yeast. J Biol Chem 264: 7603–7610 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groft CM, Burley SK (2002) Recognition of eIF4G by rotavirus NSP3 reveals a basis for mRNA circularization. Mol Cell 9: 1273–1283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie C, Fink G (1991) Guide to yeast genetics and molecular biology. Methods Enzymol 194: 1–863 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H, von der Haar T, Singh CR, Ii M, Li B, Hinnebusch AG, McCarthy JE, Asano K (2003) The yeast eukaryotic initiation factor 4G (eIF4G) HEAT domain interacts with eIF1 and eIF5 and is involved in stringent AUG selection. Mol Cell Biol 23: 5431–5445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton TM, Coldwell MJ, Carpenter GA, Morley SJ, Pain VM (2007) Functional analysis of individual binding activities of the scaffold protein eIF4G. J Biol Chem 282: 1695–1708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imataka H, Gradi A, Sonenberg N (1998) A newly identified N-terminal amino acid sequence of human eIF4G binds poly (A)-binding protein and functions in poly(A)-dependent translation. EMBO J 17: 7480–7489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahvejian A, Svitkin YV, Sukarieh R, M'Boutchou MN, Sonenberg N (2005) Mammalian poly(A)-binding protein is a eukaryotic translation initiation factor, which acts via multiple mechanisms. Genes Dev 19: 104–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye NM, Emmett KJ, Merrick WC, Jankowsky E (2009) Intrinsic RNA binding by the eukaryotic initiation factor 4F depends on a minimal RNA length but not on the m7G cap. J Biol Chem 284: 17742–17750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler SH, Sachs AB (1998) RNA recognition motif 2 of yeast Pab1p is required for its functional interaction with eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4G. Mol Cell Biol 18: 51–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaleghpour K, Svitkin YV, Craig AW, DeMaria CT, Deo RC, Burley SK, Sonenberg N (2001) Translational repression by a novel partner of human poly(A) binding protein, Paip2. Mol Cell 7: 205–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeFebvre AK, Korneeva NL, Trutschl M, Cvek U, Duzan RD, Bradley CA, Hershey JW, Rhoads RE (2006) Translation initiation factor eIF4G-1 binds to eIF3 through the eIF3e subunit. J Biol Chem 281: 22917–22932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maag D, Lorsch JR (2003) Communication between eukaryotic translation initiation factors 1 and 1A on the yeast small ribosomal subunit. J Mol Biol 330: 917–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel YM, Poncet D, Piron M, Kean KM, Borman AM (2000) Cap-Poly(A) synergy in mammalian cell-free extracts. Investigation of the requirements for poly(A)-mediated stimulation of translation initiation. J Biol Chem 275: 32268–32276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell S, Walker S, Algire M, Park E-H, Hinnebusch A, Lorsch J (2010) The 5′-7-methylguanosine cap on eukaryotic mRNAs serves both to stimulate canonical translation initiation and block an alternative pathway. Mol Cell 39: 950–962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanda JS, Cheung YN, Takacs JE, Martin-Marcos P, Saini AK, Hinnebusch AG, Lorsch JR (2009) eIF1 controls multiple steps in start codon recognition during eukaryotic translation initiation. J Mol Biol 394: 268–285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff CL, Sachs AB (1999) Eukaryotic translation initiation factors eIF4G and eIF4A from Saccharomyces cerevisiae physically and functionally interact. Mol Cell Biol 19: 5557–5564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestova TV, Kolupaeva VG (2002) The roles of individual eukaryotic translation initiation factors in ribosomal scanning and initiation codon selection. Genes Dev 16: 2906–2922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poyry TA, Kaminski A, Jackson RJ (2004) What determines whether mammalian ribosomes resume scanning after translation of a short upstream open reading frame? Genes Dev 18: 62–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevot D, Decimo D, Herbreteau CH, Roux F, Garin J, Darlix JL, Ohlmann T (2003) Characterization of a novel RNA-binding region of eIF4GI critical for ribosomal scanning. EMBO J 22: 1909–1921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu H, Garcia-Barrio MT, Hinnebusch AG (1998) Dimerization by translation initiation factor 2 kinase GCN2 is mediated by interactions in the C-terminal ribosome-binding region and the protein kinase domain. Mol Cell Biol 18: 2697–2711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid GA, Schatz G (1982) Import of proteins into mitochondria. Yeast cells grown in the presence of carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone accumulate massive amounts of some mitochondrial precursor polypeptides. J Biol Chem 257: 13056–13061 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs A (2000) Physical and functional interactions between the mRNA cap structure and the poly(A) tail. In Sonenberg N, Hershey JWB, Mathews MB (eds) Translational Control of Gene Expression, Sonenberg N, Hershey JWB, Mathews MB (eds) pp 447–465. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press [Google Scholar]

- Sachs AB, Davis RW, Kornberg RD (1987) A single domain of yeast poly(A)-binding protein is necessary and sufficient for RNA binding and cell viability. Mol Cell Biol 7: 3268–3276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonenberg N, Hinnebusch AG (2007) New modes of translational control in development, behavior, and disease. Mol Cell 28: 721–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svitkin YV, Evdokimova VM, Brasey A, Pestova TV, Fantus D, Yanagiya A, Imataka H, Skabkin MA, Ovchinnikov LP, Merrick WC, Sonenberg N (2009) General RNA-binding proteins have a function in poly(A)-binding protein-dependent translation. EMBO J 28: 58–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarun SZ Jr, Sachs AB (1997) Binding of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) to eIF4G represses translation of uncapped mRNA. Mol Cell Biol 17: 6876–6886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarun SZ, Sachs AB (1995) A common function for mRNA 5′ and 3′ ends in translation initiation in yeast. Genes Dev 9: 2997–3007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarun SZ, Sachs AB (1996) Association of the yeast poly(A) tail binding protein with translation initiation factor eIF-4G. EMBO J 15: 7168–7177 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarun SZ, Wells SE, Deardorff JA, Sachs AB (1997) Translation initiation factor eIF4G mediates in vitro poly (A) tail-dependent translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94: 9046–9051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Der Haar T, Ball PD, McCarthy JE (2000) Stabilization of eukaryotic initiation factor 4E binding to the mRNA 5′-Cap by domains of eIF4G. J Biol Chem 275: 30551–30555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von der Haar T, McCarthy JE (2002) Intracellular translation initiation factor levels in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and their role in cap-complex function. Mol Microbiol 46: 531–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei CC, Balasta ML, Ren J, Goss DJ (1998) Wheat germ poly(A) binding protein enhances the binding affinity of eukaryotic initiation factor 4F and (iso)4F for cap analogues. Biochemistry 37: 1910–1916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagiya A, Svitkin YV, Shibata S, Mikami S, Imataka H, Sonenberg N (2009) Requirement of RNA binding of mammalian eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4GI (eIF4GI) for efficient interaction of eIF4E with the mRNA cap. Mol Cell Biol 29: 1661–1669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.