Abstract

The Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic function (ECF) σM factor is activated by cell envelope stress elicited by antibiotics, and by acid, heat, ethanol, and superoxide stresses. Here, we have used several complementary approaches to identify genes controlled by σM. In many cases, expression is only partially dependent on σM due to both overlapping promoter recognition with other ECF σ factors and the presence of additional promoter elements. Genes regulated by σM have a characteristic pattern of induction in response to cell envelope-acting antibiotics as evidenced by hierarchical clustering analysis. σM also contributes to the expression of the Spx transcription factor and thereby indirectly regulates genes of the Spx regulon. Cell envelope stress responses also include regulons controlled by σW, σB, and several two-component regulatory systems (e.g. LiaRS, YycFG, BceRS). Activation of the σM regulon increases expression of proteins functioning in transcriptional control, cell wall synthesis and shape determination, cell division, DNA damage monitoring, recombinational repair, and detoxification.

Keywords: sigma factor, antibiotic, peptidoglycan, vancomycin, regulation

Introduction

The adaptation of bacteria to extracytoplasmic stresses requires mechanisms of trans-membrane signaling. Among the most common signaling mechanisms are the ubiquitous two component regulatory systems (TCS) in which a trans-membrane sensor kinase controls the activity of a cytosolic response regulator (Mascher et al., 2006), and extracytoplasmic function (ECF) σ factors in which σ factor activity is controlled by one or more trans-membrane regulators (anti-σ factors and accessory proteins) (Helmann, 2002; Ravio and Silhavy, 2001).

Bacillus subtilis encodes seven extracytoplasmic function (ECF) σ factors (Helmann, 2002). The σW regulon is the best understood and includes ~60 genes induced by the presence of cell wall-active antibiotics (Cao et al., 2002a; Cao et al., 2002b; Helmann, 2006). Mutants lacking σW have a significantly increased sensitivity to fosfomycin and a variety of antibacterial peptides and bacteriocins produced by Bacillus spp. (Butcher and Helmann, 2006; Cao et al., 2001). The σX regulon includes genes that affect peptidoglycan turnover and modulate cell surface charge, including D-alanylation of teichoic acids and synthesis of phosphatidylethanolamine (Cao and Helmann, 2004; Huang and Helmann, 1998). Mutants lacking σX have altered surface properties and an increased sensitivity to cationic antimicrobial peptides (Cao and Helmann, 2004). A number of σM dependent operons have been described, and the expression and activity of σM is elevated under acid, heat, salt, superoxide and cell envelope stresses (Cao and Helmann, 2002; Jervis et al., 2007; Minnig et al., 2003; Ohki et al., 2003b; Thackray and Moir, 2003). However, a detailed understanding of the composition, and ultimately the role, of the σM regulon is lacking.

Knowledge of the remaining ECF σ factors (σY, σV, σZ, and σYlaC) is also sparse. The σY regulon includes an autoregulated heptacistronic operon, postulated to encode a toxic peptide, and one additional verified gene (ybgB) encoding a putative immunity protein for an antimicrobial peptide (Cao et al., 2003; Tojo et al., 2003). Analysis of genes induced by overexpression of σV revealed extensive overlap with target operons that are also activated, under other conditions, dependent upon σX and/or σW (Zellmeier et al., 2005). This reflects the challenge of defining the regulons controlled by ECF σ factors when there is partial, or even extensive, overlap in promoter specificity (Cao and Helmann, 2002; Mascher et al., 2007; Minnig et al., 2003; Qiu and Helmann, 2001). It is also possible that overexpression of σV activates either synthesis or activity of other ECF σ factors. Similarly, a transcriptome analysis of gene expression as measured 2 hours after overexpression of each of the seven ECF σ factors in B. subtilis identified numerous operons that were up-regulated by multiple σ factors (Asai et al., 2003). However, it is unclear whether these proposed targets result from direct or indirect effects of σ factor activity over this long period of induction and no further analysis or promoter identification studies were reported.

As a class, ECF σ factors are often control cell envelope stress responses (Alba and Gross, 2004; Helmann, 2002; Ravio and Silhavy, 2001). Cell envelope stress can be broadly defined as resulting from chemical or genetic impairment of the assembly, maintenance, or function of the cell membranes and wall. Many antibiotics target enzymes needed for peptidoglycan biosynthesis and exposure of cells to these compounds elicits a cell envelope stress response. Other compounds may interfere with the synthesis or integrity of the cell membranes and induce a related stress response (Darwin, 2005; Raivio, 2005; Rowley et al., 2006). For example, many cationic antimicrobial peptides, bacteriocins, and some organic solvents and detergents interfere with the integrity of the cytoplasmic membrane (Bauer and Dicks, 2005; Breukink and de Kruijff, 2006; Duque et al., 2007; Martinez et al., 2007). Misfolding or overexpression of secreted proteins can also trigger envelope stress and activate the synthesis of appropriate degradation enzymes or protein chaperones (Hyyrylainen et al., 2005). While the regulatory pathways and the precise regulons differ between organisms, it is clear that envelope stresses elicit a complex set of overlapping responses to help maintain the integrity of the cell membrane and wall.

Here, we identify genes controlled by σM. In addition to confirming most of the previously assigned regulon members (Jervis et al., 2007), we provide evidence that σM contributes to the transcription of many additional operons, including genes important for cell wall biosynthesis, shape determination and cell division, DNA damage responses, and detoxification enzymes. In addition, a subset of genes previously assigned to the σX and/or σW regulons are here shown to respond to cell envelope-active compounds in a pattern characteristic of σM-dependent control.

Results and Discussion

Strategy for defining the σM regulon

In previous work, 13 promoters (controlling 18 genes) were defined as σM-dependent based, in large part, on their induction in a strain engineered to overproduce σM and the confirmation of the corresponding transcription start points by 5′-RACE (Jervis et al., 2007) (Table 1a; and references therein). In a separate study, the mRNA levels for ~50 genes were found to be up-regulated at least 3-fold 2 hours after induction of σM and were therefore assigned as candidate members of the σM regulon (Asai et al., 2003). However, this list of candidates has never been tested and appears to contain a number of false positives. Moreover, the similar promoter recognition properties of different ECF σ factors leads to overlapping recognition (Huang et al., 1998; Mascher et al., 2007; Qiu and Helmann, 2001). While in many cases these regulatory overlaps are physiologically relevant, overexpression of individual ECF σ factors may also lead to non-physiological activation of promoters normally regulated by related σ factors.

Table 1.

Genes regulated directly by σM

| Operon1 | Promoter Element2 | 5′ UTR3 | +1 Evidence4 | ECF σ 5 | WT6 (+/− Van) | sigM (+/−Van) | HC7 | ROMA8 | lacZ fusion9 | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Previously assigned σM promoters (19 genes in B. subtilis 168) | ||||||||||

| sigM yhdLK | taatgTGCAACtttaaacctttcttatgCGTGtataacaTAga | 18 | PE | M(W) | 7.2 | 1.0 | M1 | 3–4 | M | (Horsburgh and Moir, 1999) |

| yqjL | tttagAGAAACgatcggctaaggttctcCGTCtccctagtaga | 25 | RO (W) | MW | 33.2 | 1.0 | M2 | 3 | (M) | (Cao et al., 2005) |

| ypbG | acgatAGAAACgtcttttttta-ttgtcCGTCttattgatAag | 28 | RACE (2) | M | 15.2 | 0.77 | M1 | 1 | M | (Jervis et al., 2007) |

| ydaH | cgtacTGAAACctccttgtcttctttccAGTCttatctctAgg | 25 | RACE (2) | M | 20.1 | 1.0 | M1 | 3 | M | (Jervis et al., 2007) |

| yfnI | aaatgTGAAACgaaatgaaggtttctttCGTCcagtgattGgt | 184 | RACE (2) | M | 4.6 | 0.5 | M1 | 3 | M | (Jervis et al., 2007) |

| (maf)ysxA mreBCDminCD | taaatCGAAACttttcaccagaagaaaaCGTCcaatggttGgc | 460 | RACE (2) | MV(W) | 6.8 | 0.5 | M1 | (3),1–2 | MXW | (Jervis et al., 2007; Pietiainen et al., 2005; Thackray and Moir, 2003) |

| (sms)disA yacLM | ttatcTGAAACcgatatggagtatatttCGTCtgctatacAag | 890 | RACE | M | 3.2 | 1.3 | M2 | 1 | M | (Jervis et al., 2007; Thackray and Moir, 2003) |

| ypuA | aaaaaTGAAACctgaatctctttatctcCGTCtaacctaaCgg | 81 | RACE | M | [2.9] | - | M3 | - | MXW | (Jervis et al., 2007; Pietiainen et al., 2005) |

| bcrC | ttattTGAAACttttcatgagtaagattAGTCtactaaAtata | 23 | RACE | MX(VX) | 6.3 | 1.4 | M1 | 2 | (MX) | (Cao et al., 2002b; Ohki et al., 2003a; Thackray and Moir, 2003) |

| tarA [W23 strains] | taagTTGAAACgattttctt-tctgctgCGTCatttattTtgt | PE | MX | Not applicable; operon not present in 168 strains | (Huang et al., 1998; Minnig et al., 2003) | |||||

| divIC | atgttTGAAACttcttcctgtgaaaatgCGTCtaactttTAga | 113 | PE | MWX(V) | 2.8 | 0.9 | M1 | 4 | (MX) | (Huang et al., 1998; Minnig et al., 2003) |

| B. Newly defined σM promoters (18 genes) | ||||||||||

| (murG)murB divIBylxXW sbp | ttacgGGAAACccgagagcctctgaagtCGTCtcaataaaGac | 603 | RACE | (MWY) | 8.9 | 0.5 | M1 | (1)1–2 | M | This work |

| yngC | aaaatTGTAACcatcttgctcgtcaatcAGTCatataataGtg | 31 | RACE | (MX) | 2.8 | 1.0 | M1 | 2 | [1] | This work |

| ycgRQ | caaagTGAAACgatcctttcccctcctcCGTCaaacaagcagt | 58 | no product | (MVWX) | 4.8 | 0.8 | M1 | - | MXW | This work |

| recUponA | caagcTGAAACagactgccttttaagtcAGTCattgaccagcc | 214 | no product | (M) | 2.8 | 0.7 | M1 | 1 | [2] | This work |

| (ydbO-ydbP(as))-ddlmurF | cgggcTGAAACaatttcgtctcttgttgCGTCttttattaTga | 1110 | RACE | (MX) | 1.6 | 0.7 | M1,2 | 1 | [1] | This work |

| yebC | aaagaTAAAACcatttcatacgatatacCGTCatgtagatGtg | 115 | RACE | 5.8 | 4.8 | - | 4 | M | This work | |

| ywtF | gtcgcCGAAACattttacct-gctgcggCGTCcaatataaGgt | 148 | RACE | 3.2 | 0.9 | M1 | 3 | [1] | This work | |

| rodA | tcaatCGAAACatttcggtt-tatgataCGTCatatttcgTgt | 128 | RACE | 2.2 | 1.0 | M3 | 4 | M | This work | |

| ypuD | aaatgTGAAACatattcccgttatgcatCGTTatattaattAt | 88 | RACE | 13.0 | 6.8 | M2 | - | MXW | This work | |

| ytpAB | tgaagTGTAACtgatggcctat-cgtggCGTCatcttcaaTga | 265 | RACE | 1.3 | 1.0 | M2 | 2 | [1] | This work | |

| C. Previously assigned σW/X promoters activated by σM (20 genes) | ||||||||||

| ywaC | attcaTAGAACcttgcagcagacagggaCGTCtagtacatGga | 38 | RACE | W(M) | 9.2 | 1.5 | M1 | 4 | M | This work, (Cao et al., 2002a) |

| yjbC spx | aaaaaTGAAACcatggcggaagttcgcaCGTCtttatagaTgt | 76 | RO (WX) | WX | (3.3) | (1.4) | M3 | 4 | MXW | (Cao et al., 2002a) |

| yrhHIJ | tctatTGAAACatttttcaatacattgcCGTCtagttggTacc | 87 | PE | X(M) | (7.0) | (1.5) | M2,3 | 3 | M | (Huang et al., 1998) (Jervis et al., 2007) |

| abh | aagcgGGAAACtttttcaaagtttcattCGTCtaCGATaTAttG | 62 | PE | WX | 2.1 | 1.2 | M4 | 4 | - | (Huang and Helmann, 1998) |

| dltABCDE | aaaaaTGAAACtttttgagc-atctgatCGTCaaataatcAtG | 204 | PE,RO (X) | X(WV) | 2.1 | 0.8 | M3 | 1–2 | (X) | (Cao and Helmann, 2004) |

| ywnJ | ttttcTGTtACtttttgctttgttttacCGTCtatgtagttAc | 37 | PE RO(WX) | WX(M) | 3.5 | 1.0 | M2 | - | [2] | This work, (Asai et al., 2003; Cao and Helmann, 2004) |

| yceCDEFG | ttttaCGAAACtttgaTATAATaacaaaCGTAtatattagtaa | 79 | RO(W),PE | W(M) | 3.6 | 2.9 | M4 | 1–2 | (WXM) | (Cao et al., 2002a) |

| pbpX | tttttGACAACttttttagggctttattCGTCtaacaaaacgt | 39 | WX | 2.6 | 0.5 | M1 | 2 | (X) | (Cao and Helmann, 2004) | |

| rapD | taaaaTGTAACcaactgtcaatgagagcCGTCaaaagttaTga | 45 | PE | X | 1.6 | 1.0 | M2 | 1 | - | (Huang and Helmann, 1998) |

| D. Candidate promoter sites possibly recognized by σM (10 genes) | ||||||||||

| secDF | aactaTGCAACcgttgagtcatttaaaaCGTCtaattggctgg | 85 | no product | 1.0 | 0.6 | - | 1 | MXW | This work | |

| metA | tactgTGAAACcaaaaggcgtgtcagtgCGTTttatttaaaga | 106 | no product | 2.6 | 2.0 | M3 | 2 | MXW | This work | |

| yacAhprTftsH yacBC | ttattTGAAACaacgcttatcg-tgatcAGTGttttagcgctt | 139 | no product | 3.0 | 1.5 | M1,2 | 1 | [1] | This work | |

| ytnA | ctttgTGTAACagacaacaaggctttcgAGTAgtcgaaagcCt | 105 | RACE | (MV) | 1.2 | 0.4 | - | 2 | [2] | This work |

| ywbNO | aaataCAAAACaaatgatcagtcctataCGTCttatgatAaat | 94 | PE | W | 0.9 | 0.8 | M3 | 3 | [1] | (Huang et al., 1998) |

Operon structure is indicated based on distance between adjacent genes and co-regulation in transcriptome studies (Sierro et al., 2007). Initial genes in parentheses indicate an internal promoter element. In the specific case of (ydbO-ydbP(as))-ddlmurF, (as) indicates the anti-sense orientation of the ydbP gene (see Fig. 5).

Recognition elements for σM (-35 and -10 regions) and mapped start points for transcription are in bold. Note that yceC also has a σA-dependent start site (-10 region in bold).

Distance from the indicated +1 site to the start codon of the first co-directional gene.

Evidence for the indicated +1 assignment is either from 5′-RACE (RACE), primer extension (PE), or run-off transcription (RO) studies as indicated (using the holoenzyme form indicated parenthetically). RACE(2) indicates that the start site was determined both in this work and also by (Jervis et al., 2007). “no product” indicates that the indicated promoter site was not detected using 5′-RACE. References for start site determination are in the last column.

ECF σ indicates which, if any, σ factors have been previously implicated in transcription from the indicated promoter. Those σ factors indicated parenthetically were identified as factors which, when overproduced, would lead to at least a >3-fold increase in one or more gene of the corresponding operon after 2 hours of induction (Asai et al., 2003). No further evidence of promoter activity or recognition have been reported prior to the work reported herein.

Fold change refers to the first gene in the operon. Where data were not available (due to a bad spot on the array), numbers shown are for the next gene in the operon (shown in parentheses) or from previous measurements of the vancomycin stimulon (Cao et al. 2002b; shown in brackets).

HC refers to the position of the gene(s) in the hierarchical clustering diagram of Fig. 3. A “-“ indicates that the gene did not cluster within M1–M4 (note that yebC fell between clusters M2 and M3).

ROMA indicates the signal intensity of the gene(s) in the ROMA experiment of Fig. 2. The indicated a σM-dependent increase in signal intensity of: “4”, 1000–2500 units (9 genes total), “3”, 333 to 999 units (15 genes), “2”, 100–332 units (34 genes), and “1”, 40–99 units (63 genes). Some genes were not detected due to bad spots in the microarray (yjbC, ypuA, yrhH), but downstream genes in the operon were detected (except for ypuA which is monocistronic).

Inferred σ factor dependence of the cloned promoter region as judged by analysis of lacZ transcriptional fusions in this work (e.g. Fig. 6). Inferred σ factor dependencies from previous studies of reporter fusions are in parentheses. [1] indicates the promoter fusion was active, but not obviously σM dependent. [2] indicates a promoter fusion with little or no activity. “-“ indicates not tested.

Herein, we define the σM regulon and provide evidence that this extracytoplasmic function σ factor contributes to the antibiotic-inducible expression of ~57 genes (30 operons) associated with known or candidate σM-activated promoter elements, including several sites previously assigned to either or both the σX and σW regulons. A comprehensive listing of σM-regulated genes, together with a summary of evidence from this and previous studies, is presented in Table 1. In addition, several genes regulated by Spx, a transcription factor previously associated with disulfide stress responses (Zuber, 2004), are also induced by cell envelope-active compounds in a pattern consistent with σM-mediated induction.

To define the σM regulon we looked for genes that satisfy most or all of the following criteria. First, we identified genes that were induced by vancomycin, a known inducer of σM-regulated genes (Cao et al., 2002b; Mascher et al., 2003). In most cases, these genes were induced little if at all in a sigM null mutant strain. Second, we used ROMA (run-off transcription followed by microarray analysis; Caoet al., 2002a) to identify those genes transcribed by reconstituted σM holoenzyme. Third, we sought to identify plausible σM-dependent promoters using computer-based consensus searches followed by 5′-RACE to identify transcriptional start sites. For several promoters, transcriptional fusions were used to determine the relative role of σM, σW, and σX in promoter activity. Fourth, we used hierarchical clustering (de Hoon et al., 2004) to identify additional genes that were induced by cell envelope-active antibiotics in a pattern consistent with a primary role of σM in gene regulation. These four approaches converged to define a set of ~57 genes (30 operons) that are likely to be direct targets for transcriptional activation by σM under conditions of antibiotic stress (Table 1). An additional 10 genes are associated with candidate promoters which can not yet be confidently assigned to the σM-regulon (Table 1d).

Identification of σM-dependent genes in the vancomycin stimulon

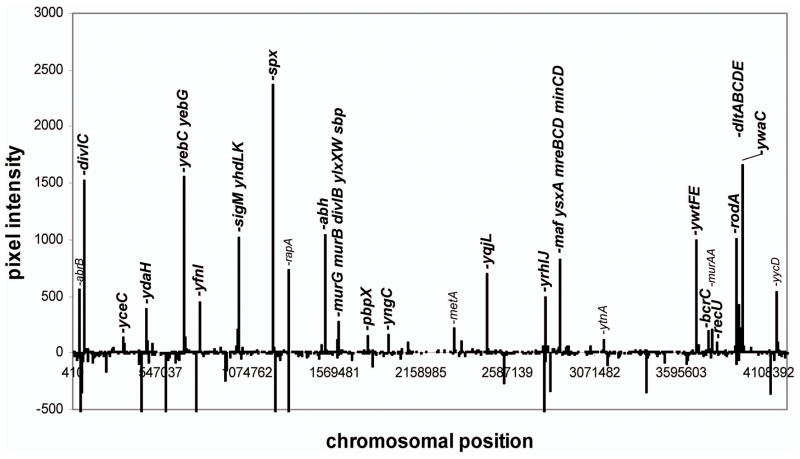

Vancomycin, an inhibitor of peptidoglycan biosynthesis, is a known inducer of both the autoregulated sigM operon and several previously described σM-regulated genes (Cao et al., 2002b; Thackray and Moir, 2003). We have used DNA microarray-based analysis to identify σM-dependent members of the vancomycin stimulon. The vancomycin stimulon includes >250 genes induced at least 2-fold after 10 min. of treatment (Fig. 1), consistent with previous studies (Cao et al., 2002b; Mascher et al., 2003). Most of the induced genes are members of known regulons including those controlled by the LiaRS TCS (Jordan et al., 2006), σW (Cao et al., 2002a), and σB (Price et al., 2001). The two most strongly induced genes, liaI and liaH, are the first two genes in the strongly activated liaI operon controlled by the cell envelope stress-inducible LiaRS TCS (Mascher et al., 2004). Vancomycin also induces genes controlled by the σY and YvrI regulatory proteins (S. MacLellan and JDH, unpublished results), and the ytrA and ywoB operons, consistent with previous studies (Cao et al., 2002b). Induction of the σB regulon by vancomycin was also noted previously (Mascher et al., 2003), although this regulon is apparently not induced by cell wall-active antibiotics in B. licheniformis (Wecke et al., 2006). Numerous other genes, as analysed herein, are known or candidate members of the σM regulon.

Figure 1.

The vancomycin stimulon. Averaged signal intensity for each gene is plotted for cells grown in the absence of vancomycin (x-axis) or presence of vancomycin for 10 min. (y-axis). Genes induced by vancomycin were assigned to regulons as indicated in the inset. “sigM(new)” indicates those genes assigned to the σM regulon in this work.

To determine which of the vancomycin-inducible genes were likely targets for σM, we determined the vancomycin stimulon in sigM mutant cells. As expected, known members of the σM regulon were induced by vancomycin in wild-type, but not in the sigM mutant (Table 1a). A number of additional genes and operons not previously assigned to the σM regulon (e.g. the murG, ycgR, recU, and ywaC operons) were also induced in a σM-dependent manner and were associated with plausible σM-dependent promoter elements (Table 1b and 1c).

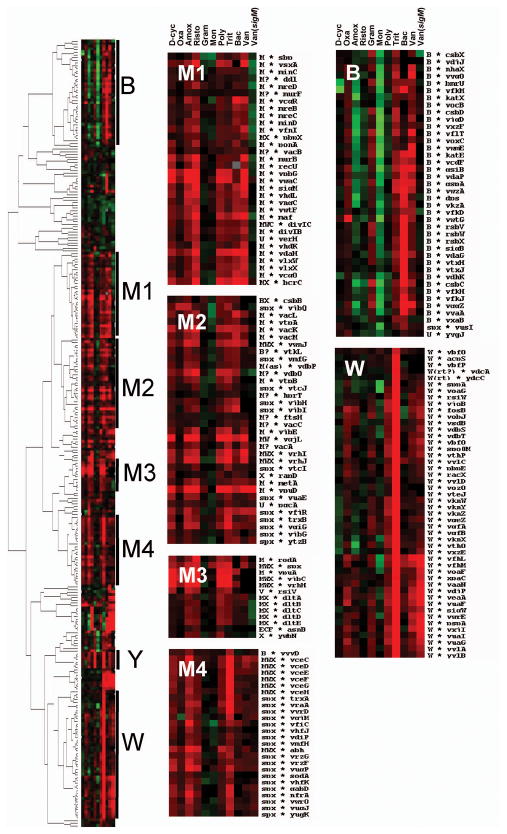

Identification of genes transcribed by σM holoenzyme in vitro using ROMA

We used ROMA (Cao et al., 2002a) to identify genes likely to be under the direct transcriptional control of σM. Total genomic DNA was transcribed in vitro by purified RNA polymerase with and without the addition of saturating levels of σM. The two RNA samples were labeled with fluorophores and hybridized to DNA microarrays as for a conventional transcriptome analysis. In this case, however, the relevant parameter is not fold-change, but rather the difference in signal intensity in the presence versus the absence of σM (Fig. 2). Absolute signal intensities are not particularly meaningful in this assay, since signal intensity depends on promoter efficiency in vitro, which is imperfectly correlated with in vivo activity. Thus, ROMA provides only a qualitative visualization of the transcriptional activity of the σM holoenzyme.

Figure 2.

σM activated genes assigned by ROMA. The σM-dependent increase in signal intensity is plotted vs. chromosome position. Note that the y-axis has been truncated so that genes with a large decrease in signal intensity are truncated at −500 pixel units (these typically result from strong σA-dependent promoters that are inhibited by addition of a large excess of σM). Gene symbols in larger font are assigned, based on the work reported herein, as at least partially σM-dependent in vivo.

There is a generally good correspondence between the ROMA results and the in vivo transcriptome analyses: many of the genes that were induced by vancomycin and appeared to be σM-dependent also gave positive signals in the ROMA assay. In other cases, genes associated with positive ROMA signals were not strongly induced by vancomycin, but were activated by other cell envelope-active compounds in a manner characteristic of σM (see below). The appearance of a positive ROMA signal suggests that these genes are likely to be direct targets for the σM holoenzyme. Indeed, of the 19 σM-dependent promoters assigned in this work (Table 1a–c), 14 correspond to positive ROMA signals. The genes that were not detectably transcribed in vitro under these conditions may require additional factors for their expression, the promoters may be relatively weak, or the promoters may be dependent on negative supercoiling for activity. Thus, there appear to be relatively few false negatives in this assay.

In contrast, the ROMA technique does yield a significant number of signals that do not correlate with our consensus list of σM-dependent promoters. Five of these may in fact be recognized by σM in vivo, but this cannot be confidently asserted based on the available date (Table 1d). Further analysis revealed that most of the remaining signals (~30 genes) result from readthrough transcription from upstream σM-dependent genes (Supplementary Material; Table S4). The high sensitivity of the ROMA assay can lead to strong signals in this in vitro assay even though the corresponding genes are not significantly affected by σM in vivo. This likely reflects the facts that transcription termination is more efficient in vivo (in the presence of additional factors such as NusA; Borukhov et al., 2005) and the expression of some of these downstream genes is normally at a sufficiently high level that readthrough transcription is not physiologically significant. For these reasons, in previous analyses we have used restriction enzyme digested genomic DNA to help limit transcription to promoter proximal regions (Cao et al., 2002a; Cao et al., 2003; Cao and Helmann, 2004).

Identification of σM-dependent promoters using consensus searches and 5′-RACE

Consensus-directed searches for promoter elements can identify a significant fraction of the genes regulated by alternative σ factors as shown in our previous work on the σW regulon (Huang et al., 1999) and in related studies of the Streptomyces coelicolorσR (Paget et al., 2001) and enterobacterial σE regulons (Rhodius et al., 2006). Here, we searched the B. subtilis genome for sequences similar to previously verified σM-activated promoter sites (Jervis et al., 2007). Since σM, σX, and σW all recognize rather similar promoter sequences (Mascher et al., 2007), this approach identified candidate promoters that may be regulated by any one (or more) of these and perhaps other ECF σ factors.

Candidate ECF-type promoters were found preceding most of the genes that were tentatively assigned to the σM regulon based on the transcriptome and ROMA experiments (Table 1). To determine whether transcription initiation events occur at these sites in vivo, we used 5′-RACE to map transcription start points in RNA samples isolated from cells treated with vancomycin. These experiments confirm the activity of 14 predicted promoter elements (Table 1) including four that were also characterized using 5′-RACE by Jervis et al. (2007) (ypbG, ydaH, yfnI and maf). Start sites for several other genes were previously determined in the course of characterizing the σX and σW regulons (Table 1a, 1c). Further, the divIC and tarA promoters from B. subtilis W23 are also controlled by both σX and σM (Minnig et al., 2003). Note that the tarA operon, required for synthesis of ribitol-based teichoic acids, is present in B. subtilis W23 strains, but not in B. subtilis 168 (which has glycerol-based teichoic acids).

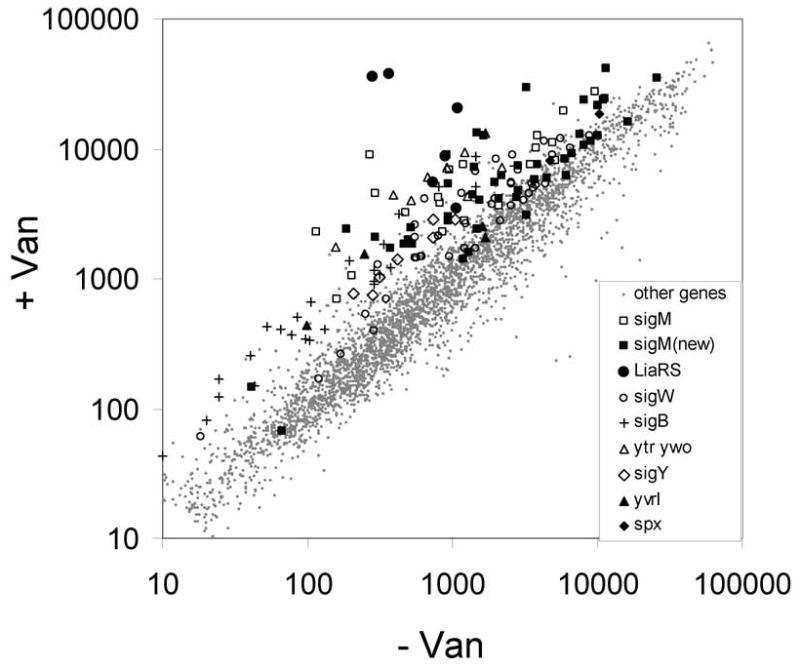

Hierarchical clustering analysis of cell envelope stress regulated genes

We reasoned that those genes primarily dependent on σM for their expression should share a common pattern of transcriptional responses in cells challenged with a variety of antibiotics. To test this hypothesis, we performed a hierarchical clustering analysis using transcriptional profiling studies of B. subtilis treated with ten different cell envelope-active compounds including bacitracin (Mascher et al., 2003), vancomycin (in both wild-type and sigM mutant cells; this study), and 8 compounds studied by Hutter et al. (2004b). As expected, genes induced by particular sets of cell envelope-active compounds tend to form discrete clusters, often corresponding to regulons. To simplify the data representation, we repeated the clustering analysis using a subset of 293 genes corresponding to the σM, σY, σW, LiaRS, and BceRS regulons, and antibiotic-inducible members of the σB, Spx, and YycFG regulons (see experimental procedures). We also included additional genes that clustered with these regulons in our initial genome-wide analysis and all other genes induced >3-fold by vancomycin.

While the precise nature of the cluster diagram varies with different sets of starting genes, most of the genes controlled (at least in part) by σM were consistently found in one or more distinct clusters, each with a similar overall pattern of responsiveness. These clusters are clearly distinguished from the σB and σW regulons (Fig. 3), and from regulons controlled by σY, LiaRS, or other stress responsive pathways. These results imply, at least for this set of stress conditions, that the contribution of σM to gene expression is sufficiently strong as to impart a characteristic response profile (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Hierarchical clustering analysis of gene expression in response to antibiotic stress. The antibiotic treatments included D-cycloserine (D-cyc), oxacillin (Oxa), amoxicillin (Amox), Ristocetin (Risto), gramicidin A (Gram), monensin (Mon), polymyxin B (Poly), Triton-X-114 (Tri), bacitracin (Bac), and vancomycin (Van) in both the wild-type and sigM mutant strains. Gene expression data was clustered based on expression level. Genes regulated by σB (B), σM (M1-M4), σY (Y), and σW (W) are highlighted. Red indicates induction, and green repression, under the specified treatment condition (see Experimental Procedures for details).

Figure 4.

Characteristic induction profile of the σM, σW, σB, σY, and Spx regulons. The induction profiles (log scale) for the clusters highlighted in Fig. 3 are compared. See Figure 3 for abbreviations.

As expected, many of the genes under the direct control of σM (e.g. cluster M1; Figs. 3 and 4) are induced by vancomycin in wild-type, but not in the sigM mutant. In contrast, the σW and σY regulons are induced in both genetic backgrounds. The σW regulon was most strongly induced by Triton-X-114 treatment, whereas σY responded strongly to both Triton-X-114 and gramicidin. For reasons that are not yet clear, induction of the σB regulon by vancomycin appeared to depend on σM. One caveat with this analysis is that our studies and those of Hutter et al. (2004b) were done in different strains of B. subtilis 168 and with differing times of exposure.

σM-dependent transcripts with unusually long 5′-untranslated regions

Most σM-dependent promoters are located adjacent to the regulated gene(s) with a predicted 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) of <200 nt. However, several exceptions are apparent (Fig. 5). As noted previously, the predicted disA (formerly yacK) and ysxA(radC) transcripts have 5′-UTRs of 890 and 459 nt, respectively (Jervis et al., 2007). The promoter upstream of disA (designated Psms) is within the radA/sms gene which encodes a paralog of the recombination protein RecA and functions in recombination-dependent DNA repair (Lovett, 2006). It is possible that an amino-terminal truncated variant of RadA/Sms could be translated from the resulting transcript, although this speculation has not yet been tested. The downstream disA gene encodes a DNA integrity scanning protein (DisA) important for sensing DNA damage (Bejerano-Sagie et al., 2006). The promoter upstream of ysxA (Pmaf) is within maf which encodes an NTPase that may function in cleansing the cellular NTP pool of xanthine and inosine triphosphates (Zheng et al., 2005).

Figure 5.

Gene organization for selected σM-regulated operons. Promoter sites are indicated by bent arrows with a subscript to indicate the relevant form(s) of holoenzyme. Genes in black are predicted to be cotranscribed based on gene organization and coexpression data (Sierro et al., 2007). The antisense oriented gene ydbP is shown in white. Transcription terminators are indicated by “lollipop” structures.

We identified two additional σM-dependent transcription units with unusually long 5′-UTRs (or possibly encoding amino-terminal truncated proteins). The promoter inside murG was confirmed by 5′-RACE and is predicted to produce a transcript with a 603 nt 5′-UTR upstream of murB. It seems unlikely that an amino-terminally truncated MurG would be functional since the missing protein region includes several active site residues (Crouvoisier et al., 2007). This candidate promoter was originally identified based on a consensus search, but strong supporting evidence emerged from analysis of its unusual pattern of induction: unlike other σM-dependent promoters, murG was apparently induced only by vancomycin and bacitracin and not by any of the antibiotics investigated by Hutter et al. (2004b). Thus, murG does not cluster with other σM-regulated genes, including those presumably encoded by the same transcript. This apparent inconsistency can be explained by the fact that the arrays used by Hutter et al. contain short dsDNA probes corresponding to the 5′-region of each gene and, in this case, the murG probe is upstream of the assigned promoter. In contrast, the arrays we have used contain either PCR products corresponding to the entire ORF (bacitracin induction experiments; Mascher et al., 2003) or ssDNA probes (65-mers; this work) from within genes (in this case, downstream of the intragenic promoter). Thus, depending on the design of the arrays, murG is either detected or not as antibiotic-inducible whereas the downstream genes in this operon (murB, divIB, ylxW, ylxX and sbp) are induced in a pattern consistent with σM regulation (cluster M1).

The promoter located within ydbO also generates a transcript with an unusually long 5′-UTR (~1110 nt) and the first co-directional gene is ddl, encoding D-ala-D-ala ligase. This promoter would also generate an antisense message for the convergent ydbP gene. Consistent with this hypothesis, apparent induction of ydbP was detected with several antibiotics investigated by Hutter et al. which, because of the dsDNA probes used in these arrays (Hutter et al., 2004b), could correspond to antisense transcripts (Fig. 3; cluster M2). Induction of this gene was not detected with the ssDNA probes used in our arrays. The ydbP gene encodes a thioredoxin-like protein thought to be under σB control (Petersohn et al., 1999). It is not yet known whether this antisense transcript is physiologically relevant, but the fact that induction of this RNA is detected in vivo would be consistent with such a role. Both ddl and murF are weakly induced by vancomycin-inducible in wild-type (1.6-, 1.3-fold, respectively; Table 1), but not in sigM mutant strains (0.7-fold), consistent with their expression from the PydbO promoter element. Weak induction (1.3 to 2.0-fold) of these genes by vancomycin was also observed in previous studies (Cao et al., 2002b; Hutter et al., 2004b) and the overall pattern of response to cell envelope-active antibiotics is consistent with σM activation (Fig. 3).

Regulation of the complex yjbC-spx operon by σM

The spx gene is subject to unusually complex regulation (Fig. 5). This gene is co-expressed with the upstream yjbC gene as a 1.2 kb transcript (Antelmann et al., 2000). Primer extension analysis of transcripts initiating upstream of yjbC revealed multiple start sites, including one corresponding to a promoter recognized in vitro by both σW and σX (Antelmann et al., 2000; Cao et al., 2002a). Both the yjbC and spx genes are induced in a strain engineered to overproduce σM (Jervis et al., 2007). In the arrays used in this study, spx was only weakly induced (3.3-fold), and there was no signal from the yjbC oligonucleotide. However, both genes are induced by vancomycin in previous studies (induction values after 10 min of 9.0- and 5.6-fold, respectively in Cao et al., 2002b; and 9.0- and 4.0-fold, respectively in Hutter et al., 2004b). Moreover, spx gives an exceptionally strong signal in the ROMA experiment (Fig. 2). Taken together, these findings lead us to suggest that the induction of spx by antibiotics likely reflects transcription from the upstream ECF-class promoter preceding yjbC (PyjbC).

The yjbC and spx genes are separated by 184 nt and spx is clearly subject to additional regulatory inputs. For example, there is a σA-type promoter (P3) immediately upstream of spx that is negatively regulated by the PerR and YodB repressors (Leelakriangsak et al., 2007; Leelakriangsak and Zuber, 2007). In addition, a σM-dependent promoter was proposed in this intergenic region (Jervis et al., 2007), although it has an atypical -10 element (TGAC) and we failed to detect promoter activity from this region when cloned as a lacZ reporter fusion (data not shown). Together with the observed co-induction of yjbC and spx, we suggest that induction of spx by cell envelope-active compounds originates from PyjbC.

Identification of antibiotic-inducible genes regulated by Spx

In the course of this work, we noted that one previously identified σM-dependent gene (yraA) was assigned an unusual promoter with a non-canonical -35 region (it lacks the “AAC” motif) and -10 region (missing the otherwise invariant GT dinucleotide) (Jervis et al., 2007). Upon closer inspection, we realized that the mapped transcription start site is preceded by plausible -35 (TTGAag) and extended -10 (TGtTATtcT) elements for σA. Moreover, a search of the literature revealed that yraA was among the genes most strongly induced by Spx (Nakano et al., 2003a). Since transcription of spx can be activated by σM (Jervis et al., 2007), we hypothesized that Spx, in turn, induced yraA.

In addition to yraA, several other genes positively activated by Spx (Nakano et al., 2003a) are also antibiotic-inducible (Fig. 3 and 4; cluster M4). The results of hierarchical clustering suggest that the induction of Spx by σM is physiologically significant. Specifically, the overall response pattern of known Spx-activated genes was more similar to the σM than to the σW regulon (Fig. 4; compare M4 with M1 and W). However, the yjbCspx operon can be induced by other ECF σ factors including σW. Indeed, Spx-regulated genes were weakly induced by vancomycin under our conditions independent ofσM, presumably reflecting activation of PyjbC by σW.

Spx has been characterized as a positive regulator of the disulfide stress response (activated by diamide) and a negative regulator of several operons controlled by two-component systems (including the ComA-dependent srfABCD operon) (reviewed in Zuber, 2004). However, Spx had not previously been implicated as a regulator of antibiotic stress-induced genes.

Determining the relative contributions of σM, σX, and σW using reporter fusions

The collective evidence of transcriptional profiling, ROMA, promoter consensus search and 5′-RACE, and hierarchical clustering analysis defines a large list of 57 genes that are likely to be direct targets for σM (Table 1). However, in some cases the observed vancomycin induction was only partially dependent onσM. This could be due to the presence of other antibiotic-inducible promoters or to overlapping recognition amongst ECF σ factors (Mascher et al., 2007). Indeed, several of the promoters herein assigned as σM-dependent were previously characterized as candidate members of the σX and/or σW regulons (Table 1c).

To further define the role of σM in directing transcription from these promoter elements, we generated a set of ectopically integrated transcriptional reporter fusions. For comparison, we included the autoregulatory site (PM) preceding sigM (Horsburgh and Moir, 1999), a site known to be completely dependent on σM for activity (Fig. 6a). A subset of the newly identified σM-dependent promoters were also largely dependent on σM for activity including ywaC, yrhH, and murG (Fig. 6a). In other cases, there was a significant amount of basal promoter activity that was independent of σM (Fig. 6b). Nevertheless, σM contributes, at least partially, to the induction observed upon exposure to vancomycin. For at least some of this latter set of promoters, the residual promoter activity is apparently due to overlapping recognition by σX and/or σW. In several cases (maf, ypuD, ycgR, metA, yjbC, secDF) promoter activity was reduced to background levels in the sigM sigX sigW triple mutant (data not shown). In three other cases (yebC, rodA, and ywtF) there was full activity even in the triple mutant. This could be due to recognition of this same site by another ECF σ factor, or possibly to the presence of an additional promoter on the cloned DNA fragment.

Figure 6.

Dependence of selected promoters on σM, σX, and σW analysed with lacZ fusions. Reporter fusions were generated with cloned promoter regions integrated ectopically into SPβ. Cells were grown to mid-logarithmic phase and either induced or not with vancomycin for 10 min. prior to assay. Strains were assayed in the genetic backgrounds indicated in the inset where CU1065 represents wild-type and sigM indicates the sigM null mutant strain.

Our hierarchical clustering results (Fig. 3) suggest that several sites previously assigned as belonging to the σX and/or σW regulons respond in a pattern consistent with a dominant role of σM in their expression. Whereas most σW-controlled genes cluster tightly together (Fig. 3; cluster W), several promoters recognized by σW (yceC, ywaC; Cao et al., 2002a) or by both σW and σX (e.g. ywbN, yjbC, and abh; Helmann, 2002) can now be seen to respond to cell envelope stress in a manner consistent with σM-regulation. Similarly, the σX-activated rapD and dltABCD operons (Cao and Helmann, 2004) respond, at least under these stress conditions, as σM-regulated operons. These findings reinforce the notion that most σW-dependent genes are exclusively expressed by σW, whereas many genes dependent on σX and/or σM have promoter sites recognized by multiple ECF σ factors.

Functional characterization of the σM regulon

The work reported here indicates that σM controls a much larger regulon than previously envisioned. Altogether, we estimate that at least 57 genes (30 operons) are associated with promoters directly responsive to σM (Table 1a–c) and another 20–30 genes are activated indirectly by Spx. Functions under the direct control of σM (Table 2) include (i) gene regulation, (ii) cell wall synthesis, shape determination, and cell division, (iii) DNA monitoring and repair, and (iv) detoxification. Presumably, up-regulation of these genes in cells exposed to inhibitors of cell wall synthesis is adaptive. However, there are clearly redundant pathways for protection against many antibiotic stresses and a sigM mutant strain does not display a significantly increased sensitivity to most cell envelope active compounds (Mascher et al., 2007). The exceptions include bacitracin (Cao and Helmann, 2002), moenomycin, SDS, and some beta-lactams (Mascher et al., 2007). This presumably reflects the redundancy in antibiotic-inducible ECF σ factor regulons since a sigM sigX sigW triple mutant is significantly increased in antibiotic sensitivity relative to a sigX sigW double mutant (Mascher et al., 2007).

Table 2.

Functional Roles ofσM-Regulated Genes

| Category (Operon)1 | Function or homology | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Regulation | ||

| sigM yhdLK | ECF σ and anti-σ factors | (Horsburgh and Moir, 1999) |

| yjbCspx | Spx transcription factor | (Zuber, 2004) |

| abh | Transition state regulator (AbrB paralog) | (Strauch et al., 2007) |

| ywaC | ppGpp synthase (putative) | (Nanamiya et al., 2007) |

| rapD | Response regulator aspartate phosphatase | (Ogura and Fujita, 2007) |

| ywtF | Transcription factor; LytR family | |

| Cell Division and Shape | ||

| divIC | Cell division; component of septosome (with DivIB) | (Minnig et al., 2003) |

| (murG)B divIB ylxXW sbp | MurB; UDP-N-acetylenolpyruvoyl glucosamine reductase. DivIB; Cell-division initiation protein | (Real and Henriques, 2006) |

| rodA | Cell-division membrane protein | (Henriques et al., 1998) |

| (maf)ysxAmreBCDminCD | Cell division and shape determination | (Daniel and Errington, 2003; Stewart, 2005) |

| Cell Envelope Synthesis | ||

| yfnI | Similar to Lipoteichoic acid synthase | (Grundling and Schneewind, 2007) |

| bcrC | Undecaprenyl pyrophosphate (UPP) phosphatase | (Bernard et al., 2005) |

| tarA (W23) | Teichoic acid (ribitol containing) | (Minnig et al., 2003) |

| (ydbO-ydbP(as))-ddlmurF | D-Ala-D-Ala ligase; MurF | |

| recUponA | PBP1; high mol. weight penicillin binding protein | (Pedersen and Setlow, 2000) |

| dltABCDE | D-alanylation of teichoic acids | (Cao and Helmann, 2004) |

| pbpX | Low molecular weight penicillin binding protein | (Cao and Helmann, 2004) |

| DNA monitoring and repair | ||

| (sms)disA yacLM | DisA; DNA integrity monitoring protein | (Bejerano-Sagie et al., 2006) |

| recUponA | RecU; Holliday junction cleavage enzyme | (Sanchez et al., 2005) |

| Detoxification | ||

| yrhHIJ | YrhH; putative methyltransferase (induced in smc mutant). YrhI; BscR regulator of cytochrome P450 expression. YrhJ; cytochrome P450 CYP102A3 | (Lee et al., 2001) |

| yqjL | Hydrolase; paraquat resistance | (Cao et al., 2005) |

| yceCDEFG | Tellurium resistance operon | |

| Miscellaneous | ||

| ytpAB | YtpA; hydrolysis of 2-sn-acyl of phosphatidylglycerol (bacilysocin synthesis) | (Tamehiro et al., 2002) |

| ? ytnA | amino acid/polyamine/organocation transporter | |

| ? metA | homoserine O-succinyltransferase | |

| ? yacA [hprT ftsHyacBC] | YacA; tRNA-modifying enzyme. HprT; hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase. FtsH; AAA family membrane protease | (Hunt et al., 2006; Ikeuchi et al., 2005) |

| ? secDF | Required for efficient protein secretion | (Bolhuis et al., 1998) |

| ? ywbNO | YwbN; peroxidase for elemental Fe uptake | (Ollinger et al., 2006) |

| Unknown Functions | ||

| ypbG | marker for inhibitionof cell wall biosynthesis | (Hutter et al., 2004a) |

| ydaH | uncharacterized membrane protein (COG0728) | |

| ypuA | marker for inhibitionof cell wall biosynthesis | (Urban et al., 2007) |

| yngC | membrane-associated protein (COG0586: DedA) | |

| ycgRQ | YcgR; Predicted permease (COG0701) | |

| yebC, ypuD, ywnJ | Hypothetical conserved |

A “?” indicates genes that are possibly activated by σM (Table 1d).

(i) σM-dependent regulatory proteins

Activation of σM enhances expression of several known or putative regulatory proteins. These include σM itself, which is cotranscribed with two membrane proteins that negatively regulate σM activity (Horsburgh and Moir, 1999). YwaC is a recently characterized ppGpp synthase, and may function to modulate gene expression (Nanamiya et al., 2007). Recently, ywaC was shown to be induced by depletion of teichoic acids or treatment with cell envelope-active antibiotics, but not antibiotics that target translation, DNA metabolism, or other functions (E. Brown, personal communication). Other candidate regulators controlled, at least in part, by σM include YwtF, a putative transcription factor related to the LytR family, the transition state regulator Abh (Strauch et al., 2007), and RapD, a putative response regulator aspartate phosphatase that negatively regulates ComA-dependent genes (Ogura and Fujita, 2007). It is interesting to note that both RapD and Spx appear to target the ComPA TCS for negative regulation (Nakano et al., 2003b).

We can speculate about the possible significance of Spx as a target of σM control. Spx controls several genes that contribute to the maintenance of a reducing intracellular environment (Nakano et al., 2005; Zuber, 2004). It has recently been suggested that many bactericidal antibiotics kill cells by the generation of reactive oxygen species (Kohanski et al., 2007). Thus, induction of the Spx regulon may help prevent cell death. It is worth noting that in Lactococcus lactis antibiotic stress activates a TCS orthologous to LiaRS (CesRS) which, in turn, activates one of seven Spx paralogs, SpxB. SpxB contributes to peptidoglycan acetylation and thereby contributes to resistance against cell wall hydrolysis (Veiga et al., 2007). The role of B. subtilis Spx in antibiotic resistance and/or cell envelope modification awaits further study.

(ii) Cell wall synthesis, shape determination, and cell division

The results presented here identify cell wall synthesis and shape determination genes as a major category of σM-regulated functions. Since many of these loci encode essential functions, it is clear that they are not exclusively under σM control. Many of these loci have multiple promoter elements and can be transcribed as complex sets of overlapping mRNAs. Nevertheless, the hierarchical clustering results imply that these loci are induced by a variety of cell envelope-active compounds with a pattern typical for σM-regulated genes.

σM also emerges as an important regulator of peptidoglycan biosynthesis enzymes (MurB, MurF, Ddl, PonA, PbpX; reviewed in Foster and Popham, 2002), a candidate lipoteichoic acid synthase (YfnI; Grundling and Schneewind, 2007), teichoic acid modification functions (Dlt operon; Cao and Helmann, 2004), and an enzyme needed for recycling of the lipid II carrier (BcrC; Bernard et al., 2005). In addition, σM contributes to the expression of several cell division proteins including DivIC, DivIB, MreB, MreC, MinC, MinD, and RodA (Bhavsar and Brown, 2006; Errington et al., 2003; Stewart, 2005). These proteins are likely to be under complex regulation. A σA-dependent promoter has also been identified upstream of divIB, for example (Harry et al., 1994). In W23, although not in 168 strains, σM also contributes directly to teichoic acid synthesis by activating transcription of the tar operon (Minnig et al., 2003).

σM also appears to activate transcription of the ytpAB operon. The YtpA protein functions in processing of membrane lipids by hydrolysis of the 2-sn-acylated fatty acid chain of phosphatidylglycerol to generate a singly acylated derivative referred to as bacilysocin (Tamehiro et al., 2002). This compound is reported to have antibacterial activity, but it is not clear if it is ever released from growing cells. Thus, this protein may actually play a role in some aspect of membrane synthesis, repair, or recycling.

(iii) DNA monitoring and repair

Activation of σM may also increase cellular defenses against DNA damage. The ysxA locus encodes a putative DNA repair gene related to E. coli radC which functions in recombinational repair. However, the original radC mutation was later found to map to recG, leaving the function of radC (and by implication, ysxA) uncertain (Lombardo and Rosenberg, 2000). As noted above, activation of the σM-dependent promoter within the sms/radA gene may lead to expression of a truncated form of the Sms/RadA protein, a RecA-like DNA binding protein important for the recombinational repair of stalled replication forks (Lovett, 2006). This same promoter activates expression of disA (formerly yacK), encoding a recently described DNA integrity scanning protein that moves rapidly along the chromosome apparently scanning for DNA damage (Bejerano-Sagie et al., 2006).

(iv) Detoxification

The σM regulon includes numerous proteins with probable functions in detoxification, although few molecular details are yet known. YqjL is a putative hydrolase that contributes to resistance to paraquat and other superoxide-generating compounds with a 2,2′-dipyridyl ring (Cao et al., 2005). The yceCDEFG operon is homologous to tellurite resistance determinants. Our results indicate that σM can also activate expression of the yrhH gene encoding a putative methyltransferase. Although the function of this gene is unknown, it has recently been shown to be induced in a mutant strain defective for Smc, the structural maintenance of chromosome protein involved in chromosome compaction and partitioning (Britton et al., 2007). Transcriptome results suggest that activation of the yrhH promoter also leads to increased expression of the downstream yrhI and yrhJ genes. Indeed, Moir and coworkers had previously assigned yrhJ to the σM regulon on the basis of studies using an integrational reporter fusion (Thackray and Moir, 2003). However, 5′-RACE studies targeted to yrhJ only identified the known σA-dependent promoter (Lee et al. 2001) in the yrhH-yrhI intergenic region (Jervis et al., 2007). The yrhI and yrhJ genes encode a regulatory protein (designated FatR; Gustafsson et al., 2001) and cytochrome P450 CYP102A3. This inducible P450 monooxygenase oxidizes long and branched-chain unsaturated fatty acids (Gustafsson et al., 2004). It has been proposed that this system might be involved in regulation of membrane fluidity or as a defense against toxic fatty acids.

The σM regulon is induced by chemical and genetic perturbation of envelope synthesis and function

Representative σM-regulated genes have been previously observed as induced by antibiotic-stress and other conditions potentially affecting the cell envelope including acid, ethanol, heat, and superoxide stresses (Thackray and Moir, 2003). In addition, genes herein assigned to the σM regulon have been previously proposed as markers for specific classes of cell envelope stress. For example, Hutter et al. (2004a) identified ypuA as gene selectively induced by cell wall synthesis inhibitors, but not by a variety of other antibiotic classes. Similarly, Brown and colleagues have identified ywaC as a gene strongly induced by depletion of teichoic acids and by several antibiotics that target the cell wall (E. Brown, personal communication). σM regulon genes are also induced by cationic antimicrobial peptides including LL-37 (Pietiainen et al., 2005). In addition, a subset were found to be significantly induced by secretion stress elicited by depletion of the PrsA foldase (Hyyrylainen et al., 2005). However, in these and related studies, the nature of the regulatory pathways controlling gene induction were generally not defined. Based on the results reported here, it appears that induction of the σM regulon in general is a good reporter for inhibition of cell envelope biosynthesis and function.

Conclusions

Here we provide our best current assessment of the scope of the σM regulon and reveal a major role for this ECF σ factor in controlling essential functions related to cell envelope biogenesis and cell division. Defining the σM regulon has been challenging, in large part because of the extensive overlap with other regulatory systems including those controlled by other ECF σ factors. Nevertheless, the strategy used here, employing a combination of in vivo and in vitro transcriptomics, hierarchical clustering, and promoter mapping and characterization has yielded a generally consistent picture and allows us to assign at least 30 operons (~57 genes) as being directly transcribed by σM. Future studies will be required to more fully characterize the physiological significance of these regulatory changes in adaptation to cell envelope stresses.

Experimental procedures

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

All B. subtilis and E. coli strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in the Supplementary Material, Tables 1–3. All B. subtilis strains were derived from wild type 168 strain CU1065. Bacteria were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C with vigorous shaking. For E. coli, 100 μg ml−1 of amplicillin was used to select for Ampr. For B. subtilis, antibiotics used for selection were as followed: 100 μg ml−1 of spectinomycin for Spcr, 10 μg ml−1 of kanamycin for Kanr, 10 μg ml−1 of neomycin for Neor, and 1 μg ml−1 of erythromycin and 25 μg ml−1 of lincomycin for macrolide-lincomycin-streptogramin B resistance (MLSr).

Construction of the spx-null mutant

A chromosomal deletion was created by long-flanking homology PCR (LFH-PCR). Flanking fragments were amplified with Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene), and the flanking fragments and antibiotic resistance gene were joined with the Expand Long Template PCR system (Roche). Primers 3819 and 3820 were used to amplify the upstream fragment, and primers 3821 and 3822 were used to amplify the downstream fragment. Detailed protocols are available at http://www.micro.cornell.edu/cals/micro/research/labs/helmann-lab/supplements.cfm.

RNA preparation and Microarray analysis

A B. subtilis microarray, consisting of 4109 gene-specific antisense oligonucleotides (65-mers; Sigma-Genosys), was printed at the W.M. Keck Foundation Biotechnology Resource Laboratory, Yale University. Each slide contains 8,447 features corresponding to duplicates of each ORF-specific oligonucleotide, additional oligonucleotides of control genes, and a 50% DMSO blank control. To identify sigM-dependent genes, three separate sets of microarray experiments were performed, including (i) a comparison of transcript levels between CU1065 with and without vancomycin, (ii) a comparison of transcript levels between CU1065 and the HB0031 (sigM::kan) strain with and without vancomycin and (iii) a comparison of transcript levels between CU1065 and HB4728 (spx::spc) strain with and without vancomycin. The cell cultures were grown to an OD600 of 0.4 and split into two flasks with equal volume, vancomycin was added to one flask to a final concentration of 2 μg ml−1 (10X MIC), and cells were harvested 10 min after treatment.The total RNA was prepared from two different cultures (biological replicates). The RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) was used to extract total RNA. DNase treatment of RNA was performed by using TURBO DNA-free™ DNase and removal reagents (Ambion). RNA concentrations were quantified using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Tech. Inc., Wilmington, DE). cDNA was synthesized and differentially labeled using the SuperScript™ Plus Indirect cDNA labeling System (Invitrogen). cDNA was generated from 20 μg of RNA using random primers in a reverse transcriptase reaction at 42°C for 2 h. cDNA was purified using a Qiagen PCR purification kit (Qiagen) prior to indirect labeling with Alexa Fluor 555 or Alexa Fluor 647 (at least 3 h at room temperature). Labeled cDNA was purified using a Qiagen PCR purification kit (Qiagen) to remove any unincorporated dye and the labeled cDNA was quantified. Both labeled cDNA populations were applied onto a microarray slide and hybridized overnight at 42°C for 16–18 h. After washing, hybridized microarray slides were analyzed using a GenePix™ 4000B array scanner (Axon Instruments, Inc.). Two microarray replicates were performed for each biological replicate. Images were processed using the GenePix Pro 4.0 software package which produces (R,G) fluorescence intensity pairs for each gene. Fluorescent signal intensities were imported into Microsoft Excel. Each expression value is represented by at least four separate measurements (duplicate spots on each of two slides). Mean values and standard deviations were calculated with Excel. The microarray datasets were filtered to remove those genes that were not expressed at levels significantly above background in either condition (sum of mean fluorescence intensity <100). In addition, the mean and standard deviation of the fluorescence intensity were computed for each gene and those where the standard deviation was greater than the mean value were ignored. The induction values were calculated by using the signal intensities of vancomycin-treated samples divided by untreated samples. Microarray datasets and related files (Microsoft Excel files and files generated using Cluster 3.0 and Treeview) are available at http://www.micro.cornell.edu/cals/micro/research/labs/helmann-lab/supplements.cfm.

Cloning, expression and purification of σM protein

The sigM gene was PCR amplified from B. subtilis chromosomal DNA with oligonuclotides designed to engineer an NcoI site upstream and a BamHI site downstream of the sigM gene. The PCR product was cloned into pET16b (Novagen) via the NcoI and BamHI sites to generate pWE01. The sequence of sigM in pWE01 was verified by DNA sequencing (Cornell DNA sequencing facility). The resultant plasmid was used to transform BL21/DE3(pLys) cells. Cells were grown to mid-logarithmic phase at 37 °C in 1 liter of LB medium and 100 mg ml−1 of ampicillin. σM expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG for 3 h at 37°C. Cells were collected by centrifugation, resuspended in 20 ml of disruption buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 2 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 233 mM NaCl, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol) and lysed with a French pressure cell at 10,000 psi followed by brief sonication, and the inclusion bodies were recovered by centrifugation. The inclusion bodies were washed twice with 10 ml TEDG buffer (10mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 10 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM DTT, 10% glycerol) containing 0.5% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 and then dissolved in 10 ml of the same buffer plus 1% (vol/vol) Sarkosyl. After centrifugation to remove the insoluble fraction, the supernatant was gradually diluted to 100 ml with TEDG–0.01% Triton X-100, to allow renaturation of σM, and then loaded onto a 5-ml Q-Sepharose (Sigma) column equilibrated with TEDG–0.01% (vol/vol) Triton X-100. After washing with 50 ml of TEDG–0.15 M NaCl–0.01% Triton X-100, σM was eluted with TEDG–0.4 M NaCl–0.01% Triton X-100. σM was further purified by chromatography on an FPLC Superdex-75 column (Amersham biosciences) in TEDG buffer containing 0.15 M NaCl followed by dialysis into TEDG–0.1 M NaCl–0.01% (vol/vol) Triton X-100–50% (vol/vol) glycerol and storage at −80°C.

Run-off transcription assay followed by microarray analysis (ROMA)

ROMA experiments were performed as described previously (Cao et al., 2002a; Cao and Helmann, 2004) with modifications. Purified σM was added in 20-fold molar excess relative to the purified RNA polymerase (mostly core with some contaminating σA). With the σM autoregulated promoter as a template, the specificity of σM-dependent transcription was optimal between 50 and 100 mM KCl (data not shown). For ROMA experiments, 100 mM KCl (final concentration) was used. Reactions (50 μl) contained 1 μg B. subtilis strain CU1065 genomic DNA which was sheared by vortexing, 0.1 μM RNAP with and without 2 μM σM, 1.25 μM δ factor mixed in transcription buffer (180 mM Tris-HCl (pH8.0), 100 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, 100 mM KCl, 10 mM DTT, 100 μg ml−1 BSA, 50% (vol/vol) glycerol, 40 units RNasin (Invitrogen) and NTP mixture (800 μM ATP, GTP, CTP and UTP). RNAP, σM and δ were mixed on ice for at least 15 minutes to form holoenzyme before the addition of template DNA. Incubation at 37°C was continued for 10 minutes to allow the binding of the holoenzyme to promoter regions. The NTPs were then added to the reaction mixture and transcription was allowed to proceed for 20 minutes at 37°C.

Reactions were terminated by addition of 200 μl stop solution (2.5 M NH4OAc, 10 mM EDTA, 15 μg ml−1 linear polyacrylamide), extracted with phenol/chloroform, and precipitated with ethanol. The RNA pellets were dissolved in 20μl DEPC-treated water and treated with TURBO DNA-free™ DNase and removal reagents (Ambion) to remove DNA templates. For each experiment, a control reaction was performed in which σM which was omitted. The cDNA synthesis, cDNA labeling and hybridization were performed as described for microarray analysis. Two or three replicate experiments were performed.

Consensus search procedures and computer analyses

All promoter consensus search protocols were performed using the SubtiList graphical interface http://genolist.pasteur.fr/SubtiList/) and the pattern search algorithm. This site allows the search to be performed on the whole genome, or limited to regions within a defined distance of annotated open reading frames. In addition, specific invariant or degenerate bases can be designated.

5′-RACE PCR

Total RNA was isolated from strain CU1065 which was induced with vancomycin as described above. 2 μg of total RNA was used as a template for reverse transcription using Multiscribe™ Revese transcriptase (Taqman, Roche) and a gene-specific primer (GSP1). The resulting cDNA was purified using a gel extraction purification kit (Qiagen) and a poly(dC) tail added at the 3′-end with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (New England Biolabs). The resulting cDNA was amplified by PCR using a poly-dG primer to anneal at the poly(dC) tail and a second gene-specific primer (GSP2), complementary to a region upstream of the GSP1 primer. PCR products were separated by gel electrophoresis and sequenced.

Hierarchical clustering analysis

Hierarchical clustering was performed using Cluster 3.0 (de Hoon et al., 2004) and transcriptome datasets derived either from this work or from previously published studies (Hutter et al., 2004b; Mascher et al., 2003). The datasets represent the following treatment conditions and times: 16 μg ml−1 D-cycloserine (40 min), 0.25 μg ml−1 oxacillin (40 min), 16 μg ml−1 amoxicillin (40 min), 0.5 μg ml−1 ristocetin (10 min), 0.03 μg ml−1 gramicidin A (10 min), 0.125 μg ml−1 monensin (10 min), 64 μg ml−1 polymyxin B (10 min), 64 μg ml−1 Triton-X-114 (10 min), 100 μg ml−1 bacitracin (5 min), 2 μg ml−1 vancomycin (wild-type; 10 min), 2 μg ml−1 vancomycin (sigM mutant; 10 min). After hierarchical clustering the output was visualized using TreeView (Eisen et al., 1998). Initial studies were done using whole genome datasets. For the cluster analysis of Fig. 3, we chose genes regulated by σM (Jervis et al., 2007), σY(Cao et al., 2003), σW (Cao et al., 2002a; Wiegert et al., 2001), the LiaRS (Jordan et al., 2006) and BceRS (Mascher et al., 2003; Ohki et al., 2003a) TCS, and antibiotic-inducible members of the σB (Price et al., 2001), Spx (Nakano et al., 2003a), and YycFG TCS (Bisicchia et al., 2007; Salzberg and Helmann, 2007). In addition, we included additional genes that clustered with these known regulons in an initial genome-wide analysis and all other genes induced at least 3-fold by vancomycin.

Construction of transcriptional fusions

Putative promoter regions were amplified from B. subtilis chromosomal DNA using a forward primer (~100 bp upstream of the -35 consensus) with restriction site HindIII and a reverse primer (typically ~50 bp downstream of the start codon) with restriction site BamHI (Table S2). The resulting fragments were digested with HindIII and BamHI and cloned into pJPM122 (Slack et al., 1991) and verified by DNA sequencing. Promoter fusions were introduced into the SPβ prophage by a double-crossover event, in which each pJPM122 derivative was linearized with ScaI and transformed into B. subtilis strain ZB307A with selection for neomycin resistance. The SPβ lysates were prepared by heat induction and used to transduce CU1065, HB0031, and HB4715.

β-Galactosidase assay

To test the promoter induction, CU1065, HB0031, and HB4715 strains containing promoter fusions were grown overnight in LB medium containing appropriate antibiotics and diluted 1:100 into 5 ml of LB medium. Each culture was grown until an OD600 ~ 0.4, the cultures were induced by adding of 2 μg ml−1 vancomycin (final concentration). The cultures were incubated for additional 30 min at 37°C then 1 ml of uninduced and induced samples were collected by centrifugation. The β-Galactosidase activity of each sample was measured according to Miller (1972).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM-047446).

References

- Alba BM, Gross CA. Regulation of the Escherichia coliσE-dependent envelope stress response. Mol Microbiol. 2004;52:613–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2003.03982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antelmann H, Scharf C, Hecker M. Phosphate starvation-inducible proteins of Bacillus subtilis: proteomics and transcriptional analysis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4478–4490. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.16.4478-4490.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai K, Yamaguchi H, Kang CM, Yoshida K, Fujita Y, Sadaie Y. DNA microarray analysis of Bacillus subtilis sigma factors of extracytoplasmic function family. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;220:155–160. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer R, Dicks LM. Mode of action of lipid II-targeting lantibiotics. Int J Food Microbiol. 2005;101:201–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejerano-Sagie M, Oppenheimer-Shaanan Y, Berlatzky I, Rouvinski A, Meyerovich M, Ben-Yehuda S. A checkpoint protein that scans the chromosome for damage at the start of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Cell. 2006;125:679–690. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard R, El Ghachi M, Mengin-Lecreulx D, Chippaux M, Denizot F. BcrC from Bacillus subtilis acts as an undecaprenyl pyrophosphate phosphatase in bacitracin resistance. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:28852–28857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413750200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhavsar AP, Brown ED. Cell wall assembly in Bacillus subtilis: how spirals and spaces challenge paradigms. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:1077–1090. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisicchia P, Noone D, Lioliou E, Howell A, Quigley S, Jensen T, Jarmer H, Devine KM. The essential YycFG two-component system controls cell wall metabolism in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 2007;65:180–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolhuis A, Broekhuizen CP, Sorokin A, van Roosmalen ML, Venema G, Bron S, Quax WJ, van Dijl JM. SecDF of Bacillus subtilis, a molecular Siamese twin required for the efficient secretion of proteins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21217–21224. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borukhov S, Lee J, Laptenko O. Bacterial transcription elongation factors: new insights into molecular mechanism of action. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:1315–1324. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breukink E, de Kruijff B. Lipid II as a target for antibiotics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:321–332. doi: 10.1038/nrd2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton RA, Kuster-Schock E, Auchtung TA, Grossman AD. SOS induction in a subpopulation of structural maintenance of chromosome (Smc) mutant cells in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:4359–4366. doi: 10.1128/JB.00132-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher BG, Helmann JD. Identification of Bacillus subtilis sigma-dependent genes that provide intrinsic resistance to antimicrobial compounds produced by Bacilli. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:765–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao M, Bernat BA, Wang Z, Armstrong RN, Helmann JD. FosB, a Cysteine-Dependent Fosfomycin Resistance Protein under the Control of σW, an Extracytoplasmic-Function σ Factor in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:2380–2383. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.7.2380-2383.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao M, Helmann JD. Regulation of the Bacillus subtilis bcrC bacitracin resistance gene by two extracytoplasmic function sigma factors. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:6123–6129. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.22.6123-6129.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao M, Kobel PA, Morshedi MM, Wu MF, Paddon C, Helmann JD. Defining the Bacillus subtilisσW regulon: a comparative analysis of promoter consensus search, run-off transcription/macroarray analysis (ROMA), and transcriptional profiling approaches. J Mol Biol. 2002a;316:443–457. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao M, Wang T, Ye R, Helmann JD. Antibiotics that inhibit cell wall biosynthesis induce expression of the Bacillus subtilisσW and σM regulons. Mol Microbiol. 2002b;45:1267–1276. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao M, Salzberg L, Tsai CS, Mascher T, Bonilla C, Wang T, Ye RW, Marquez-Magana L, Helmann JD. Regulation of the Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic function protein σY and its target promoters. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:4883–4890. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.16.4883-4890.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao M, Helmann JD. The Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic-function σX factor regulates modification of the cell envelope and resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:1136–1146. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.4.1136-1146.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao M, Moore CM, Helmann JD. Bacillus subtilis paraquat resistance is directed by σM, an extracytoplasmic function σ factor, and is conferred by YqjL and BcrC. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:2948–2956. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.9.2948-2956.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouvoisier M, Auger G, Blanot D, Mengin-Lecreulx D. Role of the amino acid invariants in the active site of MurG as evaluated by site-directed mutagenesis. Biochimie. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel RA, Errington J. Control of cell morphogenesis in bacteria: two distinct ways to make a rod-shaped cell. Cell. 2003;113:767–776. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00421-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin AJ. The phage-shock-protein response. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57:621–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Hoon MJ, Imoto S, Nolan J, Miyano S. Open source clustering software. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1453–1454. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duque E, Rodriguez-Herva JJ, de la Torre J, Dominguez-Cuevas P, Munoz-Rojas J, Ramos JL. The RpoT regulon of Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E and its role in stress endurance against solvents. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:207–219. doi: 10.1128/JB.00950-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Errington J, Daniel RA, Scheffers DJ. Cytokinesis in bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2003;67:52–65. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.1.52-65.2003. table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster SJ, Popham DL. Structure and Synthesis of Cell wall, Spore Cortex, Teichoic Acids, S-layers, and Capsules. In: Sonenshein AL, Hoch J, Losick R, editors. Bacillus subtilis and Its Closest Relatives: From Genes to Cells. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2002. pp. 21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Grundling A, Schneewind O. Synthesis of glycerol phosphate lipoteichoic acid in Staphylococcus aureus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8478–8483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701821104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson MC, Palmer CN, Wolf CR, von Wachenfeldt C. Fatty-acid-displaced transcriptional repressor, a conserved regulator of cytochrome P450 102 transcription in Bacillus species. Arch Microbiol. 2001;176:459–464. doi: 10.1007/s002030100350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson MC, Roitel O, Marshall KR, Noble MA, Chapman SK, Pessegueiro A, Fulco AJ, Cheesman MR, von Wachenfeldt C, Munro AW. Expression, purification, and characterization of Bacillus subtilis cytochromes P450 CYP102A2 and CYP102A3: flavocytochrome homologues of P450 BM3 from Bacillus megaterium. Biochemistry. 2004;43:5474–5487. doi: 10.1021/bi035904m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harry EJ, Rowland SL, Malo MS, Wake RG. Expression of divIB of Bacillus subtilis during vegetative growth. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1172–1179. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.4.1172-1179.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmann JD. The extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors. Adv Microb Physiol. 2002;46:47–110. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(02)46002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmann JD. Deciphering a complex genetic regulatory network: the Bacillus subtilisσW protein and intrinsic resistance to antimicrobial compounds. Sci Prog. 2006;89:243–266. doi: 10.3184/003685006783238290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques AO, Glaser P, Piggot PJ, Moran CP., Jr Control of cell shape and elongation by the rodA gene in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:235–247. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsburgh MJ, Moir A. σM, an ECF RNA polymerase sigma factor of Bacillus subtilis 168, is essential for growth and survival in high concentrations of salt. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:41–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Fredrick KL, Helmann JD. Promoter recognition by Bacillus subtilisσW: autoregulation and partial overlap with the σX regulon. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3765–3770. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.15.3765-3770.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Helmann JD. Identification of target promoters for the Bacillus subtilisσX factor using a consensus-directed search. J Mol Biol. 1998;279:165–173. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Gaballa A, Cao M, Helmann JD. Identification of target promoters for the Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic function σ factor, σW. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:361–371. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt A, Rawlins JP, Thomaides HB, Errington J. Functional analysis of 11 putative essential genes in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology. 2006;152:2895–2907. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.29152-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutter B, Fischer C, Jacobi A, Schaab C, Loferer H. Panel of Bacillus subtilis reporter strains indicative of various modes of action. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004a;48:2588–2594. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.7.2588-2594.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutter B, Schaab C, Albrecht S, Borgmann M, Brunner NA, Freiberg C, Ziegelbauer K, Rock CO, Ivanov I, Loferer H. Prediction of mechanisms of action of antibacterial compounds by gene expression profiling. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004b;48:2838–2844. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.8.2838-2844.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyyrylainen HL, Sarvas M, Kontinen VP. Transcriptome analysis of the secretion stress response of Bacillus subtilis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;67:389–396. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-1898-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeuchi Y, Soma A, Ote T, Kato J, Sekine Y, Suzuki T. molecular mechanism of lysidine synthesis that determines tRNA identity and codon recognition. Mol Cell. 2005;19:235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jervis AJ, Thackray PD, Houston CW, Horsburgh MJ, Moir A. SigM-responsive genes of Bacillus subtilis and their promoters. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:4534–4538. doi: 10.1128/JB.00130-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan S, Junker A, Helmann JD, Mascher T. Regulation of LiaRS-dependent gene expression in Bacillus subtilis: identification of inhibitor proteins, regulator binding sites, and target genes of a conserved cell envelope stress-sensing two-component system. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:5153–5166. doi: 10.1128/JB.00310-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, Hayete B, Lawrence CA, Collins JJ. A common mechanism of cellular death induced by bactericidal antibiotics. Cell. 2007;130:797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TR, Hsu HP, Shaw GC. Transcriptional regulation of the Bacillus subtilis bscR-CYP102A3 operon by the BscR repressor and differential induction of cytochrome CYP102A3 expression by oleic acid and palmitate. J Biochem (Tokyo) 2001;130:569–574. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a003020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leelakriangsak M, Kobayashi K, Zuber P. Dual negative control of spx transcription initiation from the P3 promoter by repressors PerR and YodB in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:1736–1744. doi: 10.1128/JB.01520-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leelakriangsak M, Zuber P. Transcription from the P3 promoter of the Bacillus subtilis spx gene is induced in response to disulfide stress. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:1727–1735. doi: 10.1128/JB.01519-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo MJ, Rosenberg SM. radC102 of Escherichia coli is an allele of recG. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:6287–6291. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.22.6287-6291.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovett ST. Replication arrest-stimulated recombination: Dependence on the RecA paralog, RadA/Sms and translesion polymerase, DinB. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5:1421–1427. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]