Abstract

Myxozoans are enigmatic endoparasitic organisms sharing morphological features with bilateria, protists and cnidarians. This, coupled with their highly divergent gene sequences, has greatly obscured their phylogenetic affinities. Here we report the sequencing and characterization of a minicollagen homologue (designated Tb-Ncol-1) in the myxozoan Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae. Minicollagens are phylum-specific genes encoding cnidarian nematocyst proteins. Sequence analysis revealed a cysteine-rich domain (CRD) architecture and genomic organization similar to group 1 minicollagens. Homology modelling predicted similar three-dimensional structures to Hydra CRDs despite deviations from the canonical pattern of group 1 minicollagens. The discovery of this minicollagen gene strongly supports myxozoans as cnidarians that have radiated as endoparasites of freshwater, marine and terrestrial hosts. It also reveals novel protein sequence variation of relevance to understanding the evolution of nematocyst complexity, and indicates a molecular/morphological link between myxozoan polar capsules and cnidarian nematocysts. Our study is the first to illustrate the power of using genes related to a taxon-specific novelty for phylogenetic inference within the Metazoa, and it exemplifies how the evolutionary relationships of other metazoans characterized by extreme sequence divergence could be similarly resolved.

Keywords: phylum-restricted gene, polar capsules, nematocysts, Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae

1. Introduction

The availability of DNA sequence information has revolutionized interpretations of the phylogenetic relationships among metazoan taxa. Initially achieved through molecular phylogenies based on 18s rDNA [1,2], subsequent phylogenomic approaches analysing multiple genes [3] are generating further inferences about metazoan evolutionary relationships. It is widely accepted that broad taxon sampling and a multi-gene approach are critical for improving the phylogenetic resolution of the metazoan tree of life [4,5]. Nevertheless, when such sampling is adopted, certain taxonomic groups can remain inherently problematic owing to extreme divergence of their DNA sequences. Furthermore, phylogenomic studies can themselves result in conflicting interpretations (e.g. regarding the placement of ctenophores [4,5]). An alternative approach to resolving the position of at least some problematic taxa is to focus on taxonomically restricted genes that can act as phylogenetic markers [6]. Analysis of genes linked to a complex character should provide a powerful approach to phylogenetic inference since these genes are unlikely to have evolved convergently. Here, we demonstrate the use of taxonomically restricted genes to inform on the much-debated phylogenetic affinities of the Myxozoa and exemplify how this approach can help to resolve impasses created by highly divergent sequence evolution among the Metazoa.

Myxozoans are endoparasites that use aquatic invertebrates (worms and freshwater bryozoans) as definitive hosts and vertebrates (typically fish) as secondary hosts, causing a number of economically important diseases in the latter [7,8]. Myxozoans were long classified as protists because of their extreme morphological degeneracy, but 18S rDNA sequence data and demonstration of multicellularity eventually confirmed a metazoan affinity [9,10]. Subsequent phylogenetic analyses based on 18S rDNA grouped myxozoans variously as a sister taxon to the Bilateria or within the Cnidaria, reflecting the extreme sequence divergence of the Myxozoa and whether the aberrant Polypodium hydriforme (a cnidarian intracellular parasite of oocytes of acipenseriform fish) was included in analyses [11]. A recent phylogenomic study based on analyses of 50 protein-coding genes [12] provided evidence that myxozoans group within the cnidarians and demonstrated the contaminant nature of Hox genes suggestive of a bilaterian affinity [13]. However, scepticism regarding myxozoan affinities remains owing to limitations of the phylogenomic study, including problems of missing data, bootstrap support of only 70 per cent, an inability to reject alternative placements under certain models, inclusion of only a small number of cnidarians and the absence of P. hydriforme genes in analyses [11,14,15]. In addition, longitudinal muscles in the worm-like myxozoan Buddenbrockia plumatellae occur as independent blocks of muscles typical of mesoderm [16], a body layer putatively lacking in cnidarians [17]. Finally, recent phylogenetic analyses combining 18S rDNA and 28S rDNA, and much broader taxon-sampling, have grouped Myxozoa with the Bilateria [11], while further studies have demonstrated relatively stable positions within both the Bilateria and the Cnidaria, depending on model selection, taxon and data-sampling [15]. The definitive placement of the Myxozoa is therefore regarded as not yet resolved [14].

All myxozoans possess intracellular organelles known as polar capsules that contain an eversible tubule used to attach to hosts (figure 1a). Nematocysts are the main diagnostic feature of the phylum Cnidaria and also consist of an intracellular capsule with an inverted tubule. Nematocysts are used for prey capture and defence. These similarities in structure and function of polar capsules and nematocysts led to early suggestions that myxozoans are cnidarians [18,19]. Recent research has provided evidence that cnidarian-specific minicollagen and NOWA (nematocyst outer wall antigen) genes encode for key functional constituents of nematocyst walls. Specifically, an interlinking minicollagen–NOWA scaffold enables nematocyst walls to withstand the extremely high osmotic pressure required for nematocysts to act as explosive organelles [20,21].

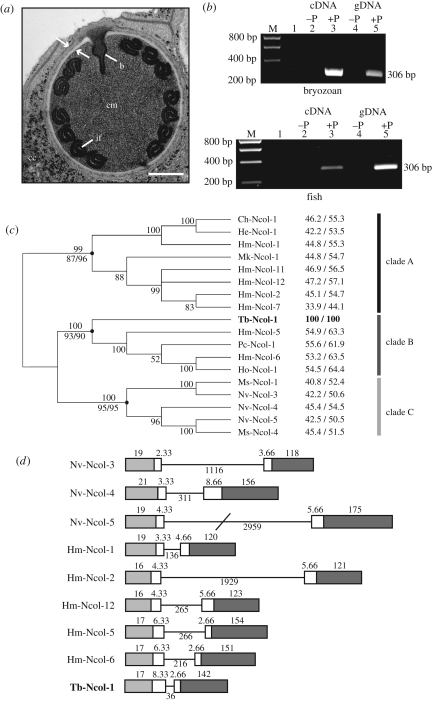

Figure 1.

Myxozoan polar capsule, PCR profiles, minicollagen phylogeny and minicollagen gene organization. (a) Transmission electron micrograph of polar capsule of an undescribed but close relative of T. bryosalmonae showing the capsule wall with characteristic electron-dense and lucent regions (arrows), the coiled inverted filament (if), the capsule matrix (cm), the base of the inverted filament (b) and thin valve cells overlying the capsulogenic cell (cc) except where the polar filament discharges. Scale bar, 0.33 µm. (b) PCR profile showing the presence of Tb-Ncol-1 in control (−P) and T. bryosalmonae-infected (+P) bryozoan (top) and rainbow trout (bottom) cDNA and genomic DNA. Lane 1, negative control (water as template). M, size marker. (c) Unrooted BI tree based on the alignment of 17 known group 1 minicollagen sequences using full-length amino acid sequences. Posterior probabilities above nodes. Bootstrap values for NJ and ML analysis below nodes with black circles. Amino acid sequence identity/similarity to Tb-Ncol-1 is on the right. Sequences partition into three groups representing known hydrozoan and cubozoan sequences with a single Gly-X-Y domain (clade A), hydrozoan sequences with a double Gly-X-Y domain (clade B) and all known anthozoan group 1 minicollagens (clade C). (d) Gene organization of known group 1 minicollagens and Tb-Ncol-1 based on sequences from the initiating ATG codon in exon I. Coding regions are represented as solid boxes. Numbers refer to corresponding amino acid number. Light grey, white and dark grey boxes represent the signal peptide, propeptide and the mature minicollagen peptide, respectively. Solid bar is the single intron within the ORF of each gene (number of basepairs below). Note conservation of the intron phase as indicated by the interrupted codon fraction. Nematostella genomic sequences obtained as in figure 2. Hydra magnipapillata genomic sequences obtained from NCBI genomes database with the genome scaffold numbers and first basepair positions as follows: Hm-Ncol-1, NW_002189376 (position 297); Hm-Ncol-2, NW_002163809 (position 52 189); Hm-Ncol-12, NW_002164275 (position 113 860); Hm-Ncol-5, NW_002161445 (position 9789); Hm-Ncol-6, NW_002160847 (position 89071).

A set of distinct domains in minicollagens are key to nematocyst wall assembly and functionality (see electronic supplementary material, figure S1). A central collagen triple helix domain (characterized by 12–16 Gly-X-Y repeats) provides flexibility to walls [22]. Adjacent are polyproline stretches of variable length followed by terminal conserved cysteine-rich domains (CRDs). The latter stabilize the capsule wall by covalently crosslinking with similar CRDs in the NOWA protein and other minicollagens, forming a highly resistant network via disulphide bonds. The unique polarity of minicollagen CRDs results in differing structures despite an identical cysteine pattern [23,24]. Such variation in the CRD domain is postulated to underlie the evolution of nematocyst complexity within the Cnidaria via the acquisition of minicollagens as novel modular units [25,26].

Here we report the sequencing and characterization of a group-1-like minicollagen gene (Tb-Ncol-1) from a cDNA library of the myxozoan Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae, the causative agent of salmonid proliferative kidney disease. The discovery of Tb-Ncol-1 provides strong support for the hypothesis that myxozoans are indeed cnidarians, suggests a direct molecular/morphological link between polar capsules and nematocysts, and demonstrates novel CRD variation relevant to the molecular evolution of minicollagen protein domain structure and folds. In addition, the discovery of Tb-Ncol-1 illustrates the power of employing taxonomically restricted genes in phylogenetic placement and represents the first example of using a gene associated with a phylum-specific morphological novelty to infer placement within the Metazoa.

2. Material and methods

(a). Gene discovery and characterization

A normalized full-length cDNA library was constructed from total RNA purified from T. bryosalmonae spore sacs (see electronic supplementary material, text file). Two hundred and eighty-eight sequenced cDNA clones were assembled and analysed with the AlignIR program (LI-COR). Sequence similarity searches were performed by BLAST [27,28] and FASTA [29]. Nucleotide and amino acid sequences representing known minicollagens were obtained from the NCBI protein and EST databases or from the TGI EST database (http://compbio.dfci.harvard.edu/tgi/). Sequences representing Nematostella vectensis minicollagen homologues were obtained from the Nematostella genome assembly ([30]; http://genome.jgi-psf.org/Nemve1/Nemve1.home.html). Multiple sequence alignments were initially generated using CLUSTALW v. 1.82 [31]. Protein size predictions and amino acid composition were determined using ProtParam (http://us.expasy.org/tools/protparam.html) and potential N-glycosylation sites identified using the NetNGlyc program (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetNGlyc/). Signal peptide prediction and protein domain architecture were assessed using the SignalP v. 3.0 program [32] and the SMART (Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool) program [33,34], respectively.

(b). Obtaining full-length cDNA and verification of gene origin

Primers to Tb-Ncol-1 were designed in the 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) to confirm the sequence corresponding to the full-length open reading frame (ORF) (F1 and R1; electronic supplementary material, figure S2), and to elucidate the genomic organization of Tb-Ncol-1 using T. bryosalmonae-infected bryozoan cDNA and genomic DNA as PCR templates. The cDNA sequence (expected product size of 564 bp) was aligned to the genomic sequence (600 bp) and the intron–exon boundaries identified using the SIM4 program [35]. Hydra minicollagen genomic sequences were obtained from the NCBI genomes database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/mapview/map_search.cgi?taxid=6085). Nematostella minicollagen sequences were obtained from the Nematostella genome assembly.

To verify that the newly discovered minicollagen homologue was T. bryosalmonae in origin, PCR analysis was conducted with primers F2 and R2, using cDNA and genomic DNA from uninfected and T. bryosalmonae-infected bryozoans and rainbow trout kidney tissue.

(c). Phylogenetic analysis

Based on the domain structure, multiple sequence alignments were generated using the MEGA v. 4.1 program [36] with gaps introduced to increase identity. Phylogenetic analyses were performed using neighbour-joining (NJ) and maximum-likelihood (ML) under JTT + I + Γ model. Bayesian inference (BI) was calculated using aamodelpr = mixed allowing the selection of the best substitution model as a parameter of the analysis. Neighbour-joining analyses were conducted within the Mega program and were bootstrapped 10 000 times. Maximum-likelihood analyses were performed in PHYML [37] and bootstrapped 500 times. Bayesian inference was performed in MrBayes v. 3.0b4 [38], with posterior probabilities based on 200 000 generations on two independent runs of four MCMC chains, with every 500th tree saved and the last 75 per cent of trees used to create the consensus tree. Amino acid sequence identities and similarities were calculated using the MatGat v. 2.02 program [39].

(d). Homology modelling

Three-dimensional models of the N- and C-terminal CRD of Tb-Ncol-1 were constructed using the homology modelling web server, ESyPred3D v. 1.0 [40], using the experimentally determined CRDs of the Hydra molecule Hm-Ncol-1 obtained from the NCBI Molecular Model Database [41] (PDB accession nos 1SOP [42] and 1ZPX [24]) as templates. Output PDB files were uploaded using the NCBI protein structure similarity search service, VAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/VAST/vastsearch), and viewed using Cn3D v. 4.1 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/CN3D/cn3d.shtml).

3. Results and discussion

(a). Tb-Ncol-1 is homologous to cnidarian group 1 minicollagens

A BLAST search demonstrated that the sequence of a cDNA clone from our full-length T. bryosalmonae cDNA library (electronic supplementary material, figure S2) was homologous to cnidarian minicollagen genes. The full-length cDNA transcript consisted of 620 bp (accession no. FN662483) that translated into a 170 amino acid ORF. The genomic sequence, determined from T. bryosalmonae-infected host genomic DNA, was 656 bp in length (accession no. FN662484). PCR analysis detected Tb-Ncol-1 in infected but not in uninfected host tissues (figure 1b), and the product was confirmed to be Tb-Ncol-1 by sequence analysis. The Tb-Ncol-1 mature peptide (142 amino acids) presents key features of minicollagens (figure 2), including a central collagen-like domain of repeated Gly-X-Y units flanked by two polyproline sequences of six (N-terminal) and seven (C-terminal) residues in length. N-terminal and C-terminal of the polyproline sequences are CRDs containing six cysteine residues arranged as CxxCxxxCxxxCxxxCC and CxxxCxxxxxCxxxCxxxCC, respectively.

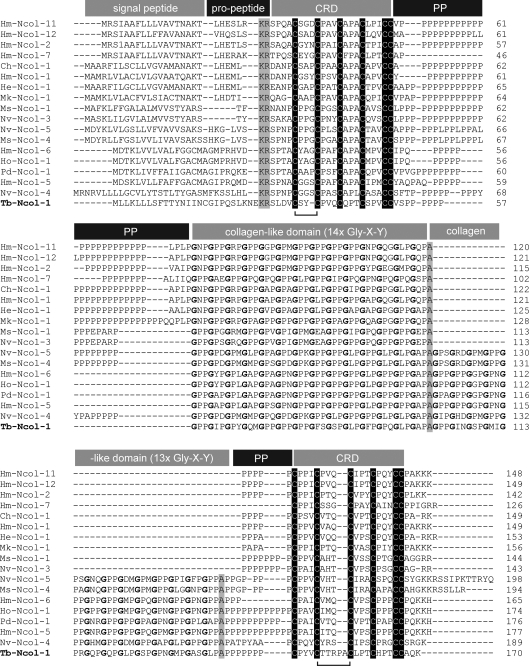

Figure 2.

Multiple alignment of the predicted Tb-Ncol-1 translation with known group 1 minicollagens. Gaps introduced to increase identity are shown by dashes. Highlighted features include the cysteine arrangement in the N- and C-terminal CRDs. Brackets indicate spatial differences between cysteines in the N-terminal and C-terminal CRDs between Tb-Ncol-1 and the canonical CRDs in other group 1 minicollagens. Predicted signal peptides, the conserved KR endopeptidase cleavage site, non-helical alanines and residues directing the three-dimensional structure, and disulphide arrangements in both CRDs are highlighted. Glycine residues in the two collagen triple helix domains are in bold. Abbreviations: Hm, Hydra magnipapillata; Ch, Clytia hemisperica; He, Hydractinia eichinata; Mk, Malo kingi; Ho, Hydra oligactis; Pd, Podocoryne carnea; Ms, Metridium senile; Nv, Nematostella vectensis; Tb, Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae. Sequences obtained from NCBI protein and EST databases under the following accession nos: Hm-Ncol-1, CAA43379; Hm-Ncol-2, CAA43380; Hm-Ncol-5, CF656203; Hm-Ncol-6, CF658139; Ch-Ncol-1, ABY71252; He-Ncol-1, DT621782; Mk-Ncol-1, ACN93684; Ms-Ncol-1, FC836938; Ms-Ncol-4, FC827212; Ho-Ncol-1, C0K091; Pd-Ncol-1, DY450665; Hm-Ncol-11, BP512837; Hm-Ncol-12, TC3264; Hm-Ncol-7, TC066. The genome scaffold and first base pair positions of the Nematostella minicollagens are: Nv-Ncol-3, scaffold 23 position 1 380 889; Nv-Ncol-4, scaffold 5 position 998 944; Nv-Ncol-5, scaffold 5 position 993 833.

Multiple amino acid alignment of Tb-Ncol-1 with medusozoan and anthozoan group 1 minicollagens (figure 2) reveals several features that specifically relate Tb-Ncol-1 to group 1 minicollagens, as opposed to group 2 or 3 minicollagens. These include the 14 + 13 arrangement of the repeating Gly-X-Y units in the central collagen-like domain and the identical cysteine sequence patterns in the two CRDs. However, there are two unique differences in the Tb-Ncol-1 CRDs. There are only two amino acids between the first and second cysteine (C1 and C2) in the N-terminal CRD, and there are five amino acids between C3 and C4 in the C-terminal CRD (figure 2). The T. bryosalmonae minicollagen sequence also shows the highest overall homology to group 1 minicollagens, with amino acid identities and similarities ranging from 33.9 to 55.6 per cent and 44.1 to 64.4 per cent, respectively (figure 1c). Homology between Tb-Ncol-1 and group 2 and 3 minicollagens was lower (29.2–41.6% identity and 34.3–55.3% similarity; electronic supplementary material, table S1). Minicollagens from groups 2 and 3 are more complex than group 1 minicollagens owing to duplication and further diversification of the two CRDs [26]. Unlike all other minicollagens, a potential N-glycosylation site (NXS/T) was detected in the second Gly-X-Y domain of Tb-Ncol-1.

(b). Tb-Ncol-1 is sister to medusozoan group 1 minicollagens

Phylogenetic analyses identified three clades of group 1 minicollagens with high percentage bootstrap confidence and high posterior probabilities (figure 1c). All medusozoan group 1 minicollagens possessing a single Gly-X-Y domain formed clade A. Tb-Ncol-1 possesses a double Gly-X-Y domain and grouped with known double Gly-X-Y-containing group 1 hydrozoan minicollagens (clade B). Anthozoan group 1 minicollagens formed clade C regardless of whether they had a single or double Gly-X-Y domain. Our phylogenetic analysis is of course limited by the paucity of available minicollagen sequences and is currently heavily biased towards hydrozoan sequences. Greater resolution of the relationship of Tb-Ncol-1 to other group 1 minicollagens requires increased representation of these genes from across the cnidaria. Also, increased sampling within myxozoans may uncover further minicollagen variants and representatives of other minicollagen groups.

(c). Genomic organization

Comparison of the T. bryosalmonae minicollagen genomic sequence with the others currently available (three Nematostella and five Hydra minicollagen group 1 genomic sequences) revealed a similar pattern of genomic organization (figure 1d). All nine sequences possess a single intron ranging in size from 36 bp in Tb-Ncol-1 to 2959 bp in Nv-Ncol-5, with the intron–exon boundaries in the Tb-Ncol-1 sequence conforming to the known GT/AG donor/acceptor site rule [43]. Exon I carries the signal peptide and exon II the mature minicollagen peptide. The pattern with which the intron interrupts the propeptide in Tb-Ncol-1 is most similar to that in the Hydra sequences, Hm-Ncol-5/6. Although our study describes the presence of a single intron in the ORF of Tb-Ncol-1, we cannot dismiss the possibility that additional introns may be present in the 5′ UTR of Tb-Ncol-1 as seen in the Hydra minicollagen, Hm-Ncol-6 [6].

(d). Predicted CRD three-dimensional structure

Minicollagens are unique among CRD-containing proteins in that dramatically different three-dimensional structures are produced from an identical cysteine sequence pattern [23,24,42]. It has been demonstrated experimentally via recombinant protein expression that single amino acid changes in CRD domains with the canonical cysteine sequence pattern can produce two three-dimensional structures [23]. These results suggest that protein evolution may proceed via intermediate ‘bridge’ states that contain novel and ancestral structures in dynamic equilibrium. Minicollagen CRDs thus provide evidence that minor sequence variation can lead to global structural switches in proteins that retain a conserved structural framework, allowing adaptive walks and structural innovation through functional intermediates [25]. As such, minicollagens contribute to an emerging view of protein dynamism and evolvability [44]. Minor variation in minicollagen CRD sequences may therefore contribute to different nematocyst morphologies achieved by distinct combinations of minicollagens and NOWA [26].

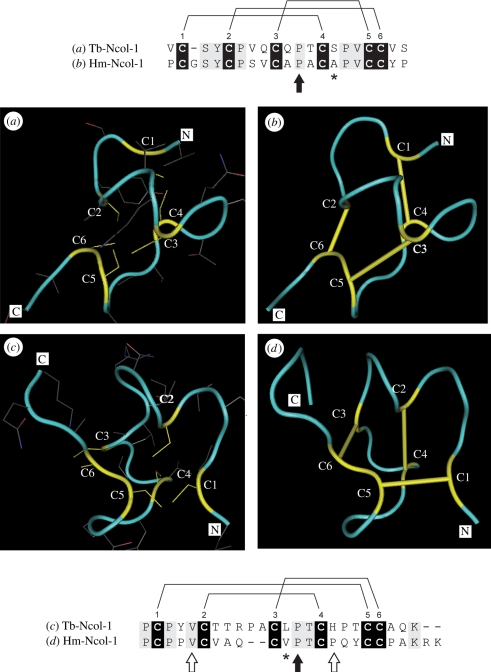

The CRDs characterized for Tb-Ncol-1 are so far unique among group 1 minicollagens, differing from both each other and the respective CRDs in other group 1 minicollagens in the number of amino acid residues in certain regions of the canonical cysteine sequence pattern [26]. Nevertheless, homology modelling predicted only minor differences between the three-dimensional CRD structures of Tb-Ncol-1 and Hm-Ncol-1 (figure 3). The amino acid deletion between C1 and C2 in the N-terminal CRD of Tb-Ncol-1 is associated with a tighter loop compared with the Hm-Ncol-1 structure. Similarly, the extra two amino acids between C2 and C3 in the C-terminal CRD of Tb-Ncol-1 are associated with a tight hairpin loop, while an open loop occurs in Hm-Ncol-1. The positions of the cysteines and side chains in the Tb-Ncol-1 CRDs are very similar to those in Hm-Ncol-1, so the same disulphide arrangement is likely to exist in the mature Tb-Ncol-1 molecule. Thus, it would be expected that intramolecular disulphide bonds would occur between C1 and C4, C2 and C6, and C3 and C5 in the N-terminal CRD, and between C1 and C5, C2 and C4, and C3 and C6 in the C-terminal CRD, as demonstrated experimentally for the Hm-Ncol-1 molecule [24,42]. Notably, the central proline between C3 and C4 in both CRDs that in Hydra directs formation of the correct disulphide linkages is conserved. Overall, these insights suggest that although certain single amino acid changes can result in major variation in three-dimensional structure [23], others will not.

Figure 3.

Tubular secondary structure representations of the N- and C-terminal CRDs of (a,c) Tb-Ncol-1 and (b,d) Hm-Ncol-1, and corresponding sequence alignments. The CRDs of Tb-Ncol-1 and Hm-Ncol-1 were aligned and three-dimensional structural models representing the Tb-Ncol-1 CRDs built using Hm-Ncol-1 N- and C-terminal CRDs as templates (PDB accession nos 1ZPX [24] and 1SOP [42], respectively). Protein backbones in blue and cysteine residues (including side chains) in yellow. Solid yellow bars are experimentally determined intramolecular disulphide bonds in the Hm-Ncol-1 CRDs. Alignments corresponding to the (a,b) N-terminal CRDs and (c,d) C-terminal CRDs indicate the known/predicted cysteine–cysteine arrangement. Cysteines are highlighted in black. All other identical residues in grey. Asterisks show amino acids of strong similarity. Black arrows show proline residues that direct the disulphide bond patterns in both CRDs. White arrows show the position of the conformation switching residues in the C-terminal CRD. Note that only the valine between C1 and C2 in the Tb-Ncol-1 C-terminal CRD is conserved.

The lack of evidence for substantial variation in three-dimensional structure in Tb-Ncol-1 relative to the Hydra minicollagen despite sequence variation is in keeping with protein structures generally being far more conserved than their sequences [45]. Nevertheless, it is of interest to speculate on the relative diversity in three-dimensional CRD structures that might be expected. Within the Myxozoa, three-dimensional CRD structural variation may be limited relative to that in the free-living cnidarians, reflecting differences in life history. Myxozoan polar capsules function solely to attach small infectious spores to hosts and their tubules are unadorned. On the other hand, nematocysts in free-living cnidarians have evolved numerous functions, including attachment to live and relatively large prey, the delivery of toxins and defence, and their tubules can possess barbs and spines that aid in these processes. At present, our insights are limited by paucity of information on minicollagen sequences, but future studies may illustrate the molecular basis for protein structure–function relationships by focusing strategically on minicollagens across the Cnidaria.

4. Conclusions

Sequencing and characterization of Tb-Ncol-1 addresses the much-debated phylogenetic position of the myxozoans by providing strong evidence for placement within the Cnidaria, and a sister-taxon relationship to the Medusozoa. Alternative hypotheses are that: (i) nematocysts did not originate in cnidarians but in protozoans [26,46]; (ii) nematocysts have been lost in bilaterians apart from unique retention in the Myxozoa. The former hypothesis could be explained by lateral organelle or gene transfer from protists that possess extrusible organelles similar to nematocysts [47–49] or the presence of nematocysts in the first metazoans [26]. However, the absence of nematocysts in sponges, ctenophores, placozoans, choanoflagellates and in bilaterians, as well as the absence of minicollagens in the genomes of representatives of relevant taxa (e.g. the placozoan Trichoplax adhaerens, the sponge Amphimedon queenslandica, the choanoflagellate Monosiga brevicollis and all bilaterian genomes sequenced to date), would have to be explained by the multiple independent loss of these characters. This renders scenarios of nematocysts in lineages other than cnidarians unlikely (apart from a protistan lineage if nematocysts originated by lateral organelle or gene transfer). Furthermore, the selective pressure for possessing nematocysts is illustrated by their retention throughout the Cnidaria and by nudibranchs that sequester nematocysts from hydroid prey. The loss of such effective organelles would be surprising. We also note that phylogenomic analyses of 50 protein-coding genes [12] provide independent evidence against the second hypothesis.

Several lines of evidence suggest that Tb-Ncol-1 is related to group 1 minicollagens, including conservation of the central Gly-X-Y domain, close similarity of the two single CRD domains, relatively high amino acid identity and similarity values, and a similar genomic organization. In addition, three-dimensional modelling of the CRD domain predicts a structure similar to that of a Hydra CRD, with minor shape variations reflecting deviations from sequence patterns characterizing all known minicollagen CRDs. More generally, our study provides strong evidence that the radiation of cnidarians as endoparasites of freshwater, marine and terrestrial hosts represents a major event in the evolution of basal metazoans. Our study also reveals novel protein sequence variation that is likely to be relevant to understanding the evolution of nematocyst complexity and reflective of a molecular/morphological link between myxozoan polar capsules and cnidarian nematocysts. Finally, our conclusions represent the first example of inferring phylogenetic placement on the basis of genes that contribute to a phylum-specific morphological novelty within the Metazoa.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by BBSRC grant BB/F003242/1. We thank Dr Jun Zou (SFIRC) for assistance with the homology modelling and Alan Curry (Manchester Royal Infirmary) for image of polar capsule. The manuscript has benefitted by comments from Drs Jun Zou, Stuart Piertney (Aberdeen University) and Alex Gruhl (Natural History Museum).

References

- 1.Halanych K. M., Bacheller J. D., Aguinaldo A. M. A., Liva S. M., Hillis D. M., Lake J. A. 1995. Evidence from 18S ribosomal DNA that the lophophorates are protostome animals. Science 267, 1641–1643 10.1126/science.7886451 (doi:10.1126/science.7886451) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguinaldo A. M. A., Turbeville J. M., Linford L. S., Rivera M. C., Garey J. R., Raff R. A., Lake J. A. 1997. Evidence for a clade of nematodes, arthropods and other moulting animals. Nature 387, 489–493 10.1038/387489a0 (doi:10.1038/387489a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunn D. W., et al. 2008. Broad phylogenomic sampling improves resolution of the animal tree of life. Nature 452, 745–749 10.1038/nature06614 (doi:10.1038/nature06614) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hejnol A., et al. 2009. Assessing the root of bilaterian animals with scalable phylogenomic methods. Proc. R. Soc. B 276, 4261–4270 10.1098/rspb.2009.0896 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0896) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Philippe H., et al. 2009. Phylogenomics revives traditional views on deep animal relationships. Curr. Biol. 19, 1–7 10.1016/j.cub.2009.02052 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.02052) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milde S., Hemmrich G., Anton-Erxleben F., Khalturin K., Wittlieb J., Bosch T. C. G. 2009. Characterization of taxonomically restricted genes in a phylum-restricted cell type. Genome Biol. 10, R8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feist S. W., Longshaw M. 2006. Phylum Myxozoa. In Fish diseases and disorders. Vol. 1: Protozoan and metazoan infections (ed. Wood P. T. K.), pp. 230–296 2nd edn. Wallingford, UK: CABI Publishing [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lom J., Dykova I. 2006. Myxozoan genera: definition and notes on taxonomy, life-cycle terminology and pathogenic species. Folia Parasitol. 53, 1–36 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smothers J. F., von Dohlen C. D., Smith L. H., Spall R. D. 1994. Molecular evidence that the myxozoan protists are metazoans. Science 265, 1719–1721 10.1126/science.8085160 (doi:10.1126/science.8085160) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lom J., Dyková I. 1997. Ultrastructural features of the actinosporean phase of Myxosporea (phylum Myxozoa): a comparative study. Acta Protozool. 36, 83–103 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans N., Lindner A., Raikova E., Collins A., Cartwright P. 2008. Phylogenetic placement of the egnimatic parasite, Polypodium hydriforme, within the Phylum Cnidaria. BMC Evol. Biol. 8, 139. 10.1186/1471-2148-8-139 (doi:10.1186/1471-2148-8-139) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiménez-Guri E., Philippe H., Okamura B., Holland P. W. H. 2007. Buddenbrockia is a Cnidarian worm. Science 317, 116–118 10.1126/science.1142024 (doi:10.1126/science.1142024) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson C. L., Canning E. U., Okamura B. 1998. A triploblast origin for Myxozoa? Nature 392, 346–347 10.1038/32801 (doi:10.1038/32801) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins A. G. 2009. Recent insights into cnidarian phylogeny. Smithsonian Contrib. Mar. Sci. 38, 139–149 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans N., Holder M., Barbeitos M., Okamura B., Cartwright P. In press The phylogenetic position of Myxozoa: exploring conflicting signals in phylogenomic and ribosomal datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. (doi:10.1093/molbev/msq159) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okamura B., Curry A., Wood T. S., Canning E. U. 2002. Ultrastructure of Buddenbrockia sp. identifies it as a myxozoan and verifies the bilaterian origin of the Myxozoa. Parasitology 124, 215–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burton J. D., Nielson H., von Heijne G., Brunak S. 2008. Insights from diploblasts: the evolution of mesoderm and muscle. J. Exp. Zool. 310B, 5–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Štolc A. 1899. Actinomyxidies, nouveau groupe de Mesozoaires parent des Myxosporidies. Bull. Int. Acad. Sci. Bohem. 22, 1–12 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weill R. 1938. L'interpretation des cnidosporidies et la valeur taxonomique de leur cnidome. Leur cycle comparé à la phase larvaire des Narcoméduses cuninides. Travaux de la Station Zoologique de Wimereaux 13, 727–744 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engel U., Pertz O., Fauser C., Engel J., David C. N., Holstein T. W. 2001. A switch in disulfide linkage during minicollagen assembly in Hydra nematocysts. EMBO J. 20, 3063–3073 10.1093/emboj/20.12.3063 (doi:10.1093/emboj/20.12.3063) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adamczyk P., Meier S., Gross T., Hobmayer B., Grzesiek S., Bachinger H. P., Holstein T. W., Özbek S. 2007. Minicollagen-15, a novel minicollagen isolated from Hydra, forms tubule structures in nematocysts. J. Mol. Biol. 376, 1008–1020 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.10.090 (doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2007.10.090) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Özbek S., Pertz O., Schwager M., Lustig A., Holstein T. W., Engel J. 2002. Structure/function relationships in the minicollagen of Hydra nematocysts. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 49 200–49 204 10.1074/jbc.M209401200 (doi:10.1074/jbc.M209401200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meier S., Jensen P. R., David C. N., Chapman J., Holstein T. W., Grzesiek S., Özbek S. 2007. Continuous molecular evolution of protein-domain structures by single amino acid changes. Curr. Biol. 17, 173–178 10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.063 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.063) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milbradt A. G., Boulegue C., Moroder L., Renner C. 2005. The two cysteine-rich head domains of minicollagen from Hydra nematocysts differ in their cystine framework and overall fold despite an identical cysteine sequence pattern. J. Mol. Biol. 354, 591–600 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.080 (doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.080) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meier S., Özbek S. 2007. A biological cosmos of parallel universes: does protein structural plasticity facilitate evolution? BioEssays 29, 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.David C. N., Özbek S., Adamczyk P., Meier S., Pauly B., Chapman J., Hwang J. S., Gojobori T., Holstein T. W. 2008. Evolution of complex structures: minicollagens shape the cnidarian nematocyst. Trends Genet. 24, 431–438 10.1016/j.tig.2008.07.001 (doi:10.1016/j.tig.2008.07.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altschul S. F., Madden T. L., Schaffer A. A., Zhang J. H., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipman D. J. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389–3402 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389 (doi:10.1093/nar/25.17.3389) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pearson W. R., Lipman D. I. 1988. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 85, 2444–2448 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2444 (doi:10.1073/pnas.85.8.2444) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Putman N., et al. 2007. Sea anemone genome reveals ancestral eumetazoan gene repertoire and genomic organisation. Science 317, 86–94 10.1126/science.1139158 (doi:10.1126/science.1139158) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J. 1994. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighing, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 4673–4680 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673 (doi:10.1093/nar/22.22.4673) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bendtsen J. D., Nielson H., von Heijne G., Brunak S. 2004. Improved prediction of signal peptides: Signal P 3.0. J. Mol. Biol. 340, 783–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Letunic I., Copley R. R., Pils B., Pinkert S., Schultz J., Bork P. 2006. SMART, 5: Domains in the context of genomes and networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, D257–D260 10.1093/nar/gkj079 (doi:10.1093/nar/gkj079) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schultz J., Copley R. R., Doerks T., Ponting C. P., Bork P. 2000. SMART: a web-based tool for the study of genetically mobile domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 231–234 10.1093/nar/28.1.231 (doi:10.1093/nar/28.1.231) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Florea L., Hartzell G., Zhang Z., Rubin G. M., Miller W. 1998. A computer program for aligning a cDNA sequence with a genomic DNA sequence. Genome Res. 8, 967–974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar S., Tamura K., Nei M. 1994. MEGA: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software for microcomputers. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 10, 189–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guindon S., Gacuel O. 2003. A simple, fast and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst. Biol. 52, 696–704 10.1080/10635150390235520 (doi:10.1080/10635150390235520) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ronquist F., Huelsenbeck J. P. 2003. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19, 1572–1574 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Campanella J. J., Bitincka L., Smalley J. 2003. MatGAT: An application that generates similarity/identity matrices using protein or DNA sequences. BMC Bioinformatics 4, 29. 10.1186/1471-2105-4-29 (doi:10.1186/1471-2105-4-29) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lambert C., Leonard N., De Bolle X., Depiereux E. 2002. ESyPred3D: prediction of proteins 3D structures. Bioinformatics 18, 1250–1256 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.9.1250 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/18.9.1250) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y., et al. 2007. MMDB: annotating protein sequences with Entrez's 3D-structure database. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, D298–D300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pokidysheva E., et al. 2004. The structure of the Cys-rich terminal domain of Hydra minicollagen, which is involved in disulfide networks of the nematocyst wall. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 30 395–30 401 10.1074/jbc.M403734200 (doi:10.1074/jbc.M403734200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Senapathy P., Shapiro M. B., Harris N. L. 1990. Splice junctions, branch-point sites: sequence statistics, identification, and applications to genome project. Methods Enzymol. 183, 252–278 10.1016/0076-6879(90)83018-5 (doi:10.1016/0076-6879(90)83018-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tokuriki N., Tawfik D. S. 2009. Protein dynamism and evolvability. Science 324, 203–207 Recent insights into cnidarian phylogeny. Smithsonian Contrib. Mar. Sci.38, 139–149. (doi:10.1126/science.1169375) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chothia C., Lesk A. M. 1986. The relation between the divergence of sequence and structure in proteins. EMBO J. 5, 823–826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Canning E. U., Okamura B. 2004. Biodiversity and evolution of the Myxozoa. Adv. Parasitol. 56, 43–131 10.1016/S0065-308X(03)56002-X (doi:10.1016/S0065-308X(03)56002-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hausmann K. 1978. Extrusive organelles in protists. Int. Rev. Cytol. 52, 197–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Raikov I. G. 1992. Unusual extrusive organelles in karyorelictid ciliates: an argument for the ancient origin of this group. BioSystems 28, 195–201 10.1016/0303-2647(92)90020-Y (doi:10.1016/0303-2647(92)90020-Y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shostak S. 1993. A symbiogenetic theory for the origin of cnidocysts in Cnidaria. BioSystems 29, 49–58 10.1016/0303-2647(93)90081-M (doi:10.1016/0303-2647(93)90081-M) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]