Abstract

Objectives To understand the perspectives of people with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) as their illness progresses, and of their informal and professional carers, to inform provision of care for people living and dying with COPD.

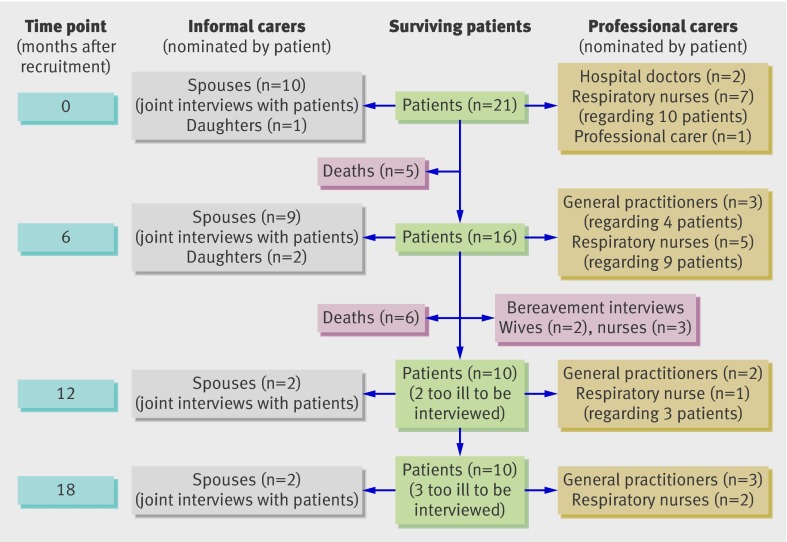

Design Up to four serial qualitative interviews were conducted with each patient and nominated carer over 18 months. Interviews were transcribed and analysed both thematically and as narratives.

Participants 21 patients, and 13 informal carers (a family member, friend, or neighbour) and 18 professional carers (a key health or social care professional) nominated by the patients.

Setting Primary and secondary care in Lothian, Tayside, and Forth Valley, Scotland, during 2007-9.

Results Eleven patients died during the study period. Our final dataset comprised 92 interviews (23 conducted with patient and informal carer together). Severe symptoms that caused major disruption to normal life were described, often in terms implying acceptance of the situation as a “way of life” rather than an “illness.” Patients and their informal carers adapted to and accepted the debilitating symptoms of a lifelong condition. Professional carers’ familiarity with the patients’ condition, typically over many years, and prognostic uncertainty contributed to the difficulty of recognising and actively managing end stage disease. Overall, patients told a “chaos narrative” of their illness that was indistinguishable from their life story, with no clear beginning and an unanticipated end described in terms comparable with attitudes to death in a normal elderly population.

Conclusions Our findings challenge current assumptions underpinning provision of end of life care for people with COPD. The policy focus on identifying a time point for transition to palliative care has little resonance for people with COPD or their clinicians and is counter productive if it distracts from early phased introduction of supportive care. Careful assessment of possible supportive and palliative care needs should be triggered at key disease milestones along a lifetime journey with COPD, in particular after hospital admission for an exacerbation.

Introduction

“Well, end stage is from the beginning, isn’t it, to a certain extent?” [F07.2 Nurse]

Globally, long term conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are responsible for an increasing proportion of deaths.1 Cancer based palliative care services, predicated on an ability to predict a terminal phase of disease,2 3 are being extended to encompass people dying with non-malignant disease.4 5 6 Prognostic indicators have been developed to aid identification of people “at risk of dying,” whose physical, psychological, social, and spiritual needs can be assessed and their care planned.2 7 There is concern, however, that the slow physical decline of patients with COPD, which is punctuated by potentially serious but unpredictable disease exacerbations, may lead to prevarication rather than provision of anticipatory care.8

About half of patients discharged after a hospital admission for COPD will die within two years.9 Markers such as severity of disease, poor nutritional status, comorbid heart disease, depression, impaired quality of life, and older age have all been shown to be associated with an overall poor prognosis.9 10 Accurate predictions of life expectancy for individual patients with COPD, however, remain extremely difficult.7 11 This difficulty with prognosis is compounded by a tendency for doctors who are familiar with patients to overestimate survival.12 The only condition where prognosis is less accurate is dementia.11

People with very severe COPD have a well recognised burden of disabling physical symptoms (especially breathlessness), compounded by comorbidity, psychological distress, and social isolation.13 14 15 16 17 Despite these issues, the needs of these patients are typically poorly addressed, and many patients have limited access to specialist palliative care services.13 14 The consultation on a strategy for services for COPD in England18 and the standards of care for COPD in Scotland19—which advocate adopting a lifelong approach to preventing, diagnosing, and providing care for people with COPD—acknowledge this deficiency and prioritise access to improved end of life care for those “sick enough to die.”

To inform current deliberations on how best to provide care for people living and dying with COPD, we undertook an in-depth inquiry seeking to understand the end of life needs of affected patients and their informal and professional carers.

Methods

Our study took place over 18 months during 2007-9. Ethical approval was obtained from the Multicentre Research Ethics Committee for Scotland (B), and governance approval was obtained from NHS Lothian, NHS Tayside, and NHS Forth Valley.

Longitudinal qualitative research using multi-perspective, serial interviews offers advantages over the more usual single “snapshot” qualitative techniques in understanding patients’ and family carers’ evolving and dynamic experience of illness (box 1).20 21 In this study, we invited patients and their nominated informal and professional carers to take part in up to four interviews at 6-9 month intervals. Multidisciplinary perspectives from the research team, an end of study workshop, and views of a lay advisory group were used to ensure breadth of interpretation of the data.22

Box 1: Features of serial multi-perspective interviews20

Advantages

Give important insights into patients’ changing experiences over the course of an illness

Enable an understanding of relationships and dynamics between patients, their families, and their professional carers

Enable an exploration of similarities and differences in the perceptions of patients and their family and professional carers

Enable an understanding of (potentially contrasting) individual needs of patients, informal carers, and professional carers

Facilitate integration of suggestions for improving services from patients, informal carers, and professional carers

Allow the development of a relationship between the patient and the researcher as a result of increased contact with participants, which facilitates discussion of sensitive issues

Disadvantages

Increased complexity of recruitment

Need to be sensitive to the disadvantages (as well as the advantages) if the patient opts for a joint interview with their informal carer

Potential for breaches of confidentiality if information from one informant is (inadvertently) relayed to another

Patient recruitment

Primary and secondary care clinicians from general practices (recruited through the Scottish Primary Care Research Network) or from hospital and community specialist respiratory services in Lothian, Tayside, and Forth Valley, Scotland, identified patients with end stage COPD. We provided information about the known predictors of a poor prognosis to aid identification of such patients,7 but specifically suggested that they should use the “surprise question”—“Would I be surprised if my patient were to die in the next 12 months?”8—to identify potential participants. We purposefully sampled to recruit men and women with different ages, social class, rurality, presence of an informal carer within the home, and current smoking status. Significant comorbidity was expected; the only exclusion criteria were inability to participate (for example, because of dementia) or other imminently life threatening illness (for example, lung cancer). A clinical assessment by a respiratory nurse established eligibility, indicators of severity, and markers known to be associated with poor prognosis.7

Recruitment of an “interview set”

At each time point, patients nominated for interview an informal carer (for example, a family member, friend, or neighbour), if they had one, and a key health or social care professional whom they regarded as important to their care at that time, thereby creating “interview sets.” The person(s) nominated could differ at different time points. Our previous studies suggested a sample of 16-20 interview sets would be sufficient to reach data saturation.20

Consent

Informed written consent was obtained from all patients at the beginning of the study and reviewed verbally before each interview. Informal and professional carers identified by the patient were asked independently for their consent to participate. Withdrawal of a patient’s consent terminated the interview set. If an informal or professional carer withdrew, interviews were allowed to continue with other members of the interview set.

Data generation

A social scientist (MK) carried out the interviews with patients and informal carers at a location of their choice, and with professional carers by phone. In-depth interviews with the patient and his or her informal carers (jointly, if preferred by the patient) were participant led, allowing people to tell their story in their own terms and at their own pace. Issues covered included the experience of living with COPD, the patient’s main concerns (whether physical, psychological, social, or spiritual), views on care and treatment, and carers’ needs and concerns (for topic guides see web appendix 1 on bmj.com). Interviews lasted between 40 and 150 minutes and were all audio recorded, with consent. Field notes were recorded after each interview.

Health and social care professionals were asked about their perception of the patients’ and informal carers’ needs, available services, and barriers to the provision of care. Bereavement interviews were, where possible, conducted with both informal and professional carers. As we came to appreciate the effect of the very long disease trajectory of COPD, we used subsequent interviews specifically to explore the patients’ “story” of their condition.

Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed and managed with a qualitative data software programme (QSR NVivo version 7; QRS International, Doncaster, Australia). Analysis was iterative throughout the study, which allowed emerging themes to be explored in later interviews; deviant cases were actively sought. The interviews with individual patients, informal carers, and professional carers were coded separately and then analysed: (a) as serial interviews with individual patients and carers to identify how needs evolved over time; (b) as integrated “patient/informal carer/professional carer” interview sets; and (c) as integrated “patient sets,” “informal carer sets,” and “professional carer sets.” Comparing and contrasting across and within these data sets highlighted emerging themes and, importantly, also divergence of perspectives.20

All transcripts were coded by MK (assisted by the study administrator), using a thematic narrative approach,23 reflecting the research questions and themes raised by the participants. We used categories informed by sociological theory on health and illness, such as Bury’s work on biographical disruption (see web appendix 2 on bmj.com).24 Frank’s typology of illness narratives was used to categorise patients’ narratives into three types: restitution, quest, or chaos (box 2).25 Restitution narratives are satisfactory stories of illness and recovery. Quest narratives tell stories of determined action and significant events that led to understanding of an illness, a search for cure, adaptation to disability, or campaigning to raise awareness or better care for the condition. By contrast, chaos narratives appear to be a disjointed series of events within which neither the narrator who is living within the story, nor the listener, can discern a clear purpose or direction.

Box 2: Frank’s typology of illness narratives

Arthur Frank’s classic text The wounded storyteller: body, illness and ethics (1995) suggests three main types of illness narrative25

1) Restitution narrative

“Yesterday I was healthy, today I am sick, but tomorrow I will be healthy again”

This narrative recounts a belief in a restoration to health and portrays illness as transitory. It is the easiest narrative to tell and to hear.

2) Quest narrative

“I have a health problem but I’m using the experience to improve the situation (for myself or others)”

In this narrative the patient uses the illness experience as an opportunity to embark on a personal quest; for example, to adjust to life with illness or to improve care and support for people with a particular condition. This narrative portrays illness as an opportunity to learn and improve, and is often found in celebrity accounts.

3) Chaos narrative

“This happened. Later on this happened. And also this happened”

This is the least heard narrative because “lived chaos” cannot be told. The story can only begin to emerge once there is an ability, however tenuous, to stand outside the chaos. Telling and hearing a chaos narrative is frustrating because it appears disjointed and without causal sequence or purpose (an anti-narrative).

The researcher and principal investigator (MK and HP) met frequently to discuss the emergent findings, to aid data synthesis and interpretation. In addition, both the lay advisory group and the multi-disciplinary steering group regularly reviewed the evolving themes and thoughts on the illness narratives in the light of their areas of expertise, knowledge of the literature, and experience.22

End of study workshop

To bridge the (typically wide) gulf between research and practice, we convened a national multi-disciplinary end of study workshop to which we invited 27 academics, policy makers, and government representatives. This allowed us not only to share and receive critical feedback on our preliminary conclusions, but also to raise awareness of our emerging findings among those responsible for service planning and provision (see web appendix 3 on bmj.com). Extensive notes were made from recordings of the four break-out groups, in which participants were invited to reflect critically on the findings and discuss and debate the implications for policy and practice.

Lay advisory group

We recruited 10 people with COPD from local “Breathe Easy” groups, a support group network run by the British Lung Foundation for people living with a lung condition and those who look after them. This lay advisory group, which was facilitated by MK, met regularly throughout the study to discuss the interview topics, the emerging findings, and the methods of disseminating the findings (see web appendix 4 on bmj.com). The comments, suggestions, and perceptions of the group were used throughout the iterative analysis process to aid interpretation. Four members of the group attended the end of study workshop.

Results

The characteristics of the 21 patients recruited to the study are given in table 1. Figure 1 gives details of the 92 interviews—23 of the patient interviews included the informal carer, and seven of the interviews with professional carers related to more than one patient. Table 2 explains our convention for describing the participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 21 patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease interviewed for the study

| Number of patients | |

|---|---|

| Sex (male/female) | 14/7 |

| Age (years; mean (SD; range)) | 71 (8; 50-83) |

| Health board | |

| Lothian | 8 |

| Forth Valley | 7 |

| Tayside | 6 |

| Demography* | |

| Inner city | 8 |

| Urban | 5 |

| Rural | 8 |

| Carer | |

| Living with family carer | 10 |

| Family carer local | 5 |

| No family carer | 6 |

| Smoking status | |

| Ex-smoker | 16 |

| Smoker | 5 |

| Comorbid disease (one or more comorbidity) | 19 |

| Clinical history | |

| Duration of symptoms (years; mean (SD)) | 18 (8) |

| Using oxygen at home | 9 |

| History of admissions for exacerbations of COPD | 13 |

| History of admissions with respiratory failure | 6 |

| Severity of COPD | |

| Spirometry FEV1 (litres; mean (SD)) | 0.63 (0.24) |

| Predicted FEV1 (%; mean (SD))† | 26 (10) |

| Oxygen saturation on air (%; mean (SD))‡ | 92 (4) |

| Medical Research Council dyspnoea score (mean (SD))§ | 4.6 (0.7) |

| Impact of disease | |

| St George’s respiratory questionnaire (mean (SD))¶ | 75.2 (11.7) |

| Hospital anxiety and depression scale, anxiety subscore (mean (SD))** | 9.4 (4.9) |

| Hospital anxiety and depression scale, depression subscore (mean (SD)) | 10.3 (4.3) |

Values are numbers of patients unless otherwise specified. COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1=forced expiratory volume in one second.

*None of the patients were from ethnic minority backgrounds.

†FEV1 <30% predicted is very severe COPD.

‡92% is the threshold for hypoxia.

§Scale 1-5, 5 is most breathless.

¶Scale 0-100, higher scores indicate worse quality of life.

**Scores above 11 indicate considerable anxiety or depression.

Fig 1 Schedule of interviews over the 18 month study

Table 2.

Conventions for describing patients and interviews

| Criterion | Example | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients | ||

| Identified by a consecutive study number and the health board in which they are registered | L = Lothian, | [L01], [L02] |

| F = Forth Valley | ||

| T = Tayside | ||

| Interviews | ||

| Patient interviews identified by the time point at which the interview took place | 1 = Baseline | [T03.1] is Tayside patient 3, baseline interview |

| 2 = 6 months | ||

| 3 = 12 months | ||

| 4 = 18 months | ||

| Informal and professional carers’ interviews indicated with reference to the patient | [F06.3 GP] is the GP nominated by Forth Valley patient 6 at the 12 month time point | |

Overview of findings

The major physical and social problems faced by the patients and their informal carers, and the considerable difficulties in accessing appropriate health and social care services, were expected findings13 14 15 16 17 and will therefore not be dwelt on in this paper. Rather, we focus on the reasons underpinning why current strategies for extending palliative care services to people living and dying with COPD is proving such a challenge 8 and suggest alternative approaches to the current policy direction.

Our report is structured under the following themes:

I Acceptance of COPD as “a way of life”

II The story of COPD

I Acceptance of COPD as “a way of life”

Apparent throughout the patients’ interviews was a sense of “acceptance” in the face of severe disease and social difficulties. COPD was something that had to be coped with “as best you can” [F07.1]. Distressing breathlessness was accepted as “the way it has worked out” [F02.1]. Patients did not actively seek out information about their condition; indeed several patients indicated that they would “rather not know” [F07.1]. For many patients their situation was made considerably worse by unsuitable housing that they seemed powerless to influence, leaving them to “do the best you can with what you’ve got” [F02.1].

“Oh I don’t ask for anything do I? So, if I asked I think I would get, I am quite sure I would because I do get excellent help from the doctors, so as I say I don’t ask . . . we manage as we are, yes, but for how long I don’t know.” [F10.1]

Although this passivity might be construed negatively, or as weary resignation to insurmountable problems, in some contexts it could also be seen as representing an appropriate adaptation to a way of life.

Interviewer: “What has helped you most over these last two years that I’ve been coming to see you?”

Patient F10.4: “Learning to accept it. To stop fighting against it and just accept it in my mind.”

The only exception was a relatively young patient with α1 antitrypsin deficiency. He and his wife had actively searched for information on the internet, joined a national organisation for people with “Alpha 1,” and campaigned to improve their circumstances.

“I’ve done a lot of shouting at the council for four years to get re-housed and it didn’t do much. I had to threaten them with a lawsuit.” [L06.1 wife]

II The story of COPD

An early observation was the contrast between the chaotic stories told by people with COPD and the well constructed and rehearsed narratives of people with, for example, lung cancer.26 Patients with COPD struggled to tell a coherent illness story distinct from their life story. These data are summarised in table 3.

Table 3.

The story of COPD: comparing and contrasting perspectives

| Patient perspective | Patient perspective: the exception (patient with α1 antitrypsin deficiency) | Professional perspective |

|---|---|---|

| 1) A story with no beginning | 1) Well rehearsed story of a dramatic diagnosis | 1) Insidious onset |

| I’ve had it forever | A dramatic beginning | Long history |

| “How it started is anybody’s guess; there is no way of knowing . . . so it has always been my belief that something happened in my younger years that started the damage.” [T06.1] Interviewer: “So when did it start?” “Um I think I was, I mean I’ve always been bothered with bronchitis and things like that through my life.” [L03.1] |

“I suppose the first place to start would be in diagnosis, really wouldn’t it, official diagnosis was August 98.” [L06.1 wife] “Slowly deteriorating from about 92-93, I started noticing getting breathless and getting worse and worse. Now I am a carpet fitter, and I mean a lot of flats and everything, it was up and down stairs and this is getting worse. I was a smoker but it never bothered me before so I thought I have to stop this, so I did cut down on cigarettes, went to the doctor and got inhalers, take that home try that one, try that one not working, try that one, changed doctor and that is when in 98 he finally found out that it was this ‘Alpha 1’ thing. Nothing they could do for it so that was the day before we got married.” [L06.1] Interviewer: “Oh my goodness!” “Day before the wedding we found out he was basically a dying man.” [L06.1 wife] Interviewer: “Good heavens, how awful!” “So my lungs was away and I was 41.” “Because I was always active as a worker like, 18 hours a day sometimes, always busy then suddenly it was stop, because I couldn’t do it anymore.” [L06.1] |

“He has got a huge file because he has been known to us for quite a long time . . . the first time I met him was 1999 when I was asked by the GP to go out and do a home visit because he was having an exacerbation of COPD . . . but he had been given a nebuliser by a predecessor, that was in 1996, after he saw the consultant.” [F09.1 nurse] |

| I’ll tell you about a milestone . . . | Insidious onset preceding diagnosis | |

| “About 18 months ago. It started off as a chest infection that I couldn’t get rid of. It was going and it sort of cleared up then a month later it was back again.” [T01.1] | “Six or seven years. Six or seven years since it became . . . initially informally and then formally diagnosed the actual COPD problem, so I think I have seen her more than anybody over the years.” [F10.1 GP] “He was only diagnosed not so long ago, he has probably had COPD for years but official diagnosis was just about 18 months ago, like from the hospital he was diagnosed years ago in the community but he had a couple of near death experiences and that was when I got told.” [F07.1 nurse] |

|

| . . . and choose a different milestone in subsequent accounts | ||

| “It started when he broke his ribs. He fell off the ladder about four years ago and broke his ribs and then he got a chest infection and any time he coughed he broke his ribs again.” [T01.4 daughter in a joint interview with her father] | ||

| I’ll link it with the story of another health problem | ||

| “I had a major op in the Infirmary in, 1985 was it? No, no, 94, 93. I had an abscess on the bowel. They thought I had cancer. I was worried.” [L04.1] | ||

| I can’t tell you “when” so I’ll tell you “how” | ||

| Interviewer: “So when did it all start?” “Well first of all it was with smoking. I was a smoker and just couldn’t stop.” [T02.1] Interviewer: “So when did it all start?” “See he was a smoker ...” [T05.1 wife] “We used to put that rubber on carpets and vulcanise it . . . we didn’t realise that we were inhaling all that smoke.” [T05.1] | ||

| 2) A middle that is a way of life | 2) Emotional upheaval and a quest | 2) A way of life for clinicians? |

| Part of ageing | Coming to terms with a long term illness | Only “ill” with exacerbations |

| “I fear I am getting worse (which is understandable), it’s like any other illness. It’s like ageing, you are getting older and that really is the illness is getting worse as well.” [F06.1] “I’m all right if I sit still. It’s all just part of getting older I suppose.” [T03.1] |

“Yes, as I say we have been through the whole spectrum of emotions with it. The denial part is the hard one because . . . now we can discuss things quite openly without fear of ornaments getting thrown and things like that but when he was going through his denial phase, it was all my fault.” [L06.1 wife] | “People like Mr X who doesn’t really bother us that much, we really only see him when he’s not well.” [F08.1 GP] |

| Nothing to be done | Quest for information, support, and appropriate care | An established routine |

| “Oh it’s certainly not very pleasant no, but that’s the way it worked out, you know I tried it, it’s not going to work for me whatever the reason. There’s nothing can be done.” [F02.1] | “After I did the research on the internet we thought, well, we can’t surely be the only people with this disease, there must be somebody else out there that we can ask or whatever.” [L06.1] “We joined a British based Alpha 1 support group, which is purely Alpha 1 sufferers and their families, and we went to a meeting at Swindon a couple of years back.” [L06.1] “I’ve done a lot of shouting at the council for four years to get re-housed and it didn’t do much I has to threaten them with a lawsuit.” [L06.1 wife] |

Interviewer: “I was going to ask you whether you have talked to him at all about what might happen in the future and how things might progress.” “No, not really. He usually has got his own [agenda in the consultation]. It’s more reassurance about how he is and chatting generally and he just likes a bit of social discourse I think.” [L04.1 GP] |

| Exacerbations are isolated episodes | Longstanding relationships | |

| “Now I’m fine, but I had a bad time over Christmas. I got a chest infection at the beginning of December and it took me till Feb to shake it off. But no, I’m fine again now. Back to normal.” [T01.4] | “We know them so well, and we’ve always been able to do something, and then it’s that part where for the rest literally what can we do?” [F07.2 nurse] | |

| 3) An uncertain and unlooked for end | 3) Discussed and planned for | 3) An uncertain and unlooked for end |

| I don’t know when | I don’t know when | I don’t know when |

| Interviewer: “So, I’ll come and see you again in about 6 months time . . .” “If I am still alive in 6 months time.” Interviewer: “I hope you will be, do you think you might not be?” “I don’t know.” [L04.1] |

“‘We can give him morphine’ [The consultant] said. ‘Now, the downside of the morphine is it will do one of two things, it will either be he will just sleep away or it will calm his breathing down enough to let us start treatment’.” [L06.1 wife] | “Is this it? Another year? Three years?” [F09.1 nurse] “. . . he has been knocking on deaths door a few times now. I think the last time he came into the Royal we really didn’t think he was going to make it through the night, never mind go home.” [L06.1 hospital doctor] |

| Unlooked for | Planning for the future | Unlooked for |

| “Even the doctor said that, it won’t get any better. What I thought, actually I could stay in the same sort of level . . .” [F07.3] “So. I certainly don’t think I’m getting any better, but I haven’t got any worse I don’t think.” [F10.4] |

“It wasn’t a difficult decision for me actually because having spoken about it at length before, you know, when he had bad episodes, about, you know, what we wanted to happen etc.” [L06.1 wife] | “Very occasionally I’ll bring it [death] up but no . . . I don’t think generally they think they are going to die of that, of COPD.” [T01.1 nurse] “. . . we are all going to die aren’t we, but it is a case of picking the time and place [to discuss it].” [L06.1 hospital doctor] |

A story with no beginning

It proved impossible for our participants to identify a “beginning” to their COPD story. Some simply acknowledged that they had “always been bothered” [L03.1] with symptoms that dated back to their “younger years” [T06.1]. Others identified a milestone (for example, point of diagnosis or a severe exacerbation) and used it as a beginning, although it was clear that disabling symptoms had preceded this beginning by many years. A different beginning could be selected in subsequent accounts, demonstrating the fluidity of the stories.

Some patients responded with well structured stories of unrelated health problems (“I had a major op in the infirmary . . . They thought I had cancer.” [L04.1]). Others answered the question of “when?” by explaining “how” smoking or their job had caused the symptoms.

Interviewer: “So when did it all start?”

Informal carer T05.1 [wife]: “See he was a smoker . . .”

Patient T05.1: “We used to put that rubber on carpets and vulcanise it . . . we didn’t realise that we were inhaling all that smoke.”

The insidious onset and lack of clear beginning to the disease was echoed by the clinicians, who described a point of “formal diagnosis of the actual COPD problem” [F10.1 GP] that was preceded by years of an “informal” recognition of the developing symptoms.

The exception again was the patient with α1 antitrypsin deficiency, who told a dramatic and well rehearsed story about how the diagnosis was confirmed the day before his wedding. Although he acknowledged that he had been “slowly deteriorating” for many years before diagnosis, the story was told as a sudden disruption to life.

Informal carer L06.1 wife: “Day before the wedding we found out he was basically a dying man.”

Interviewer: “Good heavens, how awful!”

Patient L06.1: “So my lungs was away and I was 41.

Interviewer: “That must have been a shock.”

Informal carer L06.1 [wife]: “Slightly!”

Patient L06.1: Because I was always active as a worker like, 18 hours a day sometimes, always busy then suddenly it was stop, because I couldn’t do it anymore.”

A middle that is a way of life

Unlike the narratives of people with cancer and heart failure, where accounts of the period from diagnosis are characterised by a clear sense of a developing plot with one event leading to another,26 the patients with COPD told “chaos narratives” characterised by directionless stories that were typically indistinguishable from their life story and natural ageing.

“I fear I am getting worse (which is understandable), it’s like any other illness. It’s like ageing, you are getting older and that really is the illness is getting worse as well.” [F06.1]

The participants told illness narratives about their exacerbations (for example, being increasingly breathless and rushed into hospital) or a referral for assessment for lung transplantation (such as having high hopes that were dashed after complex assessments at a distant hospital). Exacerbations were described as independent episodes interrupting “normal” life; there was little sense of a linkage, or a developing trajectory. The very slow evolution of COPD meant that some participants who had experienced a long interval between exacerbations were almost able to tell a “restitution narrative.” Table 4 shows a restitution narrative told by a 75 year old man [T01] who was able to describe himself as “well” after several months in which his very severe COPD was relatively stable. This is set against a background of a chaos narrative in which little changes over the 18 month study.

Table 4.

An example of a “restitution narrative” told against a background of a “chaos narrative” in which little changes over the 18 months study

| Time point | Quotation | Context and field notes recorded immediately after the interview |

|---|---|---|

| Interview one (May 2007) | “It started off as a chest infection that I couldn’t get rid of. It was going and it sort of cleared up then a month later it was back again. Then that sort of cleared up and finally got it cleared up then, but then it was largely my fault because I have always been one for ‘oh I’ll work it off’: just didn’t work off.” | The episode selected as the beginning of the story was the one that finally triggered a diagnosis of COPD. He blames his lifestyle rather than an underlying disease for the slow resolution. |

| Interviewer: “What have you been told about your illness, the cause and treatment, and the progress?” “Well, I’ve been told; I think I’ve been told what they know, which isn’t really a great deal considering.” “I’ve never heard of COPD. I think it’s just a catch all for asthma, bronchitis, emphysema, and that.” |

Typically for a chaos narrative, there is a general lack of enquiry about and “evaluation” of this new diagnosis perhaps because in reality he had been symptomatic for many years. | |

| Interview two (November 2007) | “I had been having a lot of chest infections, had two in three weeks, but now I feel fine again. I am not so tired as I used to be and I am breathing better, not much but . . . I am getting on better at the gym. I am actually feeling much better.” | The researcher’s field notes record a fragmented conversation in which he was “trying to give me answers but with no story to give.” |

| Descriptions of intermittent chest infections interrupt times when he is back to “normal.” | ||

| Interview three (July 2008) | Interviewer: “So how are you?” “I’m very well. Well, I feel very well. They tell me I’m not.” |

The most positive of the interviews because the patient has not had an exacerbation for some months, allowing him to tell an upbeat public story which is almost a restitution narrative. |

| Interviewer: “I really just came to catch up with you know, what’s happened since last time.” “Well, I’ve improved!” |

There is, however, a dual narrative: in reality nothing has changed. | |

| “Nothing’s changed. Same old same old! And I’m quite happy with that.” | ||

| Interview four (May 2009) | “Now I’m fine, but I had a bad time over Christmas. I got a chest infection at the beginning of December and it took me till Feb to shake it off. But no, I’m fine again now. Back to normal.” | The field notes describe a “punctured tale of recovery” owing to a troublesome exacerbation. |

| At the end of the study the researcher noted “his story is that things are the same after two years—they are not worse, they are not better either, so now we are back to the chaos narrative.” |

Although clinicians were aware of the chronic deteriorating nature of COPD, they told a parallel story of a “way of life” and colluded (at least linguistically) with the idea that the patient was “well” between exacerbations.

“People like Mr X who doesn’t really bother us that much, we really only see him when he’s not well.” [F08.1 GP]

By contrast, the patient with α1 antitrypsin deficiency and his wife told a classic “quest” narrative. They knew and accepted that the story would end in his death, but were determined to use the intervening time fighting to improve care for him and others with the condition.

“They’re not interested in people like us, as I say, well, because we’ve got . . . the wrong illness, the wrong age, well, they’ve freely admitted he’s too young!” [L06.3 wife]

An unpredictable and unanticipated end

Patients were aware that their symptoms were severe and appreciated that the future was uncertain, but—consistent with the chaos narrative—“the end” was described in terms reminiscent of a normal expectation of death rather than as an anticipated consequence of an unfolding story. In keeping with findings from surveys of attitudes to death among the public in the United Kingdom,27 our participants were aware of their own mortality (for example, an 85 year old patient commented that she “did not know” whether she would still be alive for future interviews[L05.1]). Death, however, was generally not considered as an imminent threat, and end of life wishes were generally not discussed with professional carers, friends, or family.

“I know when the nurse first said, ‘I’m referring you to [a day centre run by the local hospice]’ I thought oh God! This isn’t terminal! Not me!” [T01.3]

In telling the story of an exacerbation, several patients said “I thought I was going to die” (in the past tense), but in keeping with the restitution narrative of the acute attack, once they were restored to normal the threat receded. Interestingly, the professional carers sometimes used language that echoed the patients’ normalisation of the prospect of death.

“. . . we are all going to die aren’t we? But it is a case of picking the time and place [to discuss it].” [L06.1 hospital doctor]

Professional carers were aware that patients were deteriorating, but a transition point for palliative care was elusive. The uncertain prognosis (“Is this it? Another year? Three years?” [F09.1 nurse]) was universally cited as a barrier, but there were other more subtle influences of particular relevance in the context of long standing relationships. Some professional carers struggled with moving from “always being able to do something” to acknowledging “for the rest literally what can we do?” [F07.2 nurse]. In contrast to consultations with people with cancer where “I think it seems to come up more naturally to talk about [death]” [L03.1 GP], a familiar and comfortable pattern of consulting prevented initiating an unlooked for discussion about the future.

Interviewer: “I was going to ask you whether you have talked to him at all about what might happen in the future and how things might progress?”

Professional carer L04.1 [GP]: “No, not really. He usually has got his own [agenda in the consultation]. It’s more reassurance about how he is and chatting generally and he just likes a bit of social discourse I think.”

Again, an exception was the patient with α1 antitrypsin deficiency, who was one of only two participants in our study to have discussed the end with his doctors. He and his wife spoke openly from the very beginning of the first interview about his death and their plans for it. When faced with a decision about the use of morphine in a potentially life threatening exacerbation, his wife referred to their plans for future care.

“It wasn’t a difficult decision for me actually because having spoken about it at length before, you know, when he had bad episodes, about, you know, what we wanted to happen etc.” [L06.1 wife]

End of study workshop: comments on the data

Participants in the end of study workshop offered additional explanations for our observation of acceptance of the way of life among patients with COPD and debated the practicalities of providing supportive end of life care in the context of a condition in which it is not possible to identify a time point for transition to the palliative care approach (box 3).

Box 3: Extracts from the notes for the four multidisciplinary discussion groups at the end of project workshops

A way of life

“‘Living with COPD’ is a better term. The beginning of the dying process is the first cigarette in the bicycle shed at the age of 12.” [Group IV]

“No beginning for the healthcare professional, because it is already advanced before the professional realises there is a story.” [Group II]

“The trajectory—slowly going down. Every time they come out of hospital they go down a step—it’s not dramatic. Cancer is dramatic; the start to COPD is ‘boring’.” [Group II]

“Earlier diagnosis is making it even harder—very long trajectory.” [Group III]

Passive acceptance

“Are we talking about the professionals or the patients . . .???” [Group II]

“Could be adaptation—a way of dealing with the problem, getting on with their lives around this problem. Not necessarily a bad thing.” [Group III]

“Key is acknowledgement that one has a health condition that threatens ones life. Patients with COPD only accepted that they had an illness when they were in hospital or had an infection—otherwise life was ‘normal.’” [Group I]

Transition to palliative care

“It’s not about transition, it’s about integration.” [Group II]

“The difficult prognosis is a ‘cop out’ because the need is there. Can still support people.” [Group I]

“At least if they are on the register, someone in the practice is talking to them, whereas they are forgotten otherwise.” [Group II]

“Might be useful to think of milestones. Hospital admission (or second hospital admission) is the obvious one—should that trigger a change of gear?” [Group III]

Comparison with cancer care

“Applying the cancer model across the board is inappropriate.” [Group I]

“We have picked up the term ‘palliative care’ from cancer, maybe we need a different language?” [Group IV]

Discussion

Summary of findings

The participants in our study described severe symptoms that caused major disruption to normal life, but often in terms implying acceptance of the situation as a way of life rather than an illness. The chaos narratives of their disease stories were impossible to distinguish from their life stories, lacked a clear beginning, and had an unpredictable and unanticipated end. Professional carers’ perspectives echoed this chaos narrative, contributing to the difficulty in defining a point when palliative care might be appropriate. The policy focus on identifying a time point for transition to palliative care has little resonance with these accounts from patients, informal carers, and professional carers, and may be counterproductive if it distracts professional carers from timely consideration of providing much needed supportive care.

Passive acceptance, weary resignation, or comfortable adaptation?

The social and clinical burden described by our study participants reflects accounts in the current literature.13 14 15 16 17 Some researchers have commented on a sense of “sad resignation”28 and a tendency for people with COPD to “marginalise” their condition as the result of “old age.”29 Delegates at the end of study workshop suggested a range of explanations for this “passive acceptance,” including “stoicism,” “weary resignation” after years of futile attempts to improve their circumstances, “recalibration” analogous to the response shift recognised in quality of life research,30 or an adaptive coping strategy. Habraken et al attributed the “silence” of people with end stage COPD to them considering their limitations as normal and regarding themselves as ill only during acute exacerbations.31 Our data support this interpretation and enable us to offer a theoretically based interpretation.

Not so much an illness, more a way of life

In her seminal book Hard earned lives: accounts of health and illness from East London (1984), Cornwell identifies three categories of health problems: normal illnesses, real illnesses, and health problems that are not illnesses (table 5).32 Although our study participants all recognised the current “reality” of their illness, the lack of story, the causal link with lifestyle, and the lifelong trajectory of the disease suggest that, despite the severity of their symptoms, they classified COPD as a health problem that is not an illness. Symptoms were described as stemming from a lifetime of exposure to fumes, smoking, or both, and breathlessness was considered “part of getting older.” By contrast, exacerbations were often classified as real illnesses, but once the acute episode was over patients felt they were “back to normal.” The only exception was the man with α1 antitrypsin deficiency, in whom a genetic cause, a clear medical diagnosis, a young age, and severe symptoms signified a real illness.

Table 5.

Categories of health problems according to Cornwell’s book Hard earned lives: accounts of health and illness from East London32

| Features | |

|---|---|

| Normal illnesses | Acute conditions that medicine recognises and treats successfully. Childhood ailments and commonplace, relatively minor infections are typical examples. |

| Real illnesses | Chronic disabling conditions or more severe or life threatening conditions that medicine has a partial ability to treat. Conditions such as diabetes or epilepsy that have a clear medical diagnosis, a significant effect on the patient, and that require ongoing treatment are typical of “real illnesses.” Seeking medical advice is thus an appropriate response to having a real illness. |

| Health problems that are not illnesses | Problems associated with normal processes (for example, age related arthritis or hearing loss) or stem from the person’s lifestyle (e.g. a backache in a man with a heavy job). “Health problems that are not illnesses” are to be “coped with”; seeking medical advice is not necessarily appropriate. |

The lack of biographical disruption

The term “biographical disruption” describes the major disruptive experience of developing a chronic illness and the consequent rethinking of a person’s biography and self concept.24 33 34 More recently, the idea of a “biographically anticipated” event35—exemplified by older peoples’ experience of osteoarthritis36 and stroke37—considers that for some people in some circumstances, certain illnesses can be a “normal crisis.” Our findings extend these concepts by showing that in a very slowly progressive condition such as COPD, patients may have no sense of biographical disruption at all. In such individuals there is no illness narrative separate from their life narrative—rather, our study shows that people gradually adjust their sense of self over the years to fit within the limitations imposed by the condition. This lack of disruption may be at the root of the patients’ and carers’ acceptance and passivity, such that they neither demand nor use services. Clinicians, especially those who have a long term relationship with the patient, may share this passive acceptance of the patient’s way of life, contributing to the difficulties in identifying a transition point to palliative care.

The lack of a public story

Cancer has a well publicised “public story” in which death plays a prominent role.38 People with cancer are aware that they have a potentially fatal condition and tell a dual narrative of despair (“I’m going to die”) balanced by hope (“but I might get better”).23 By contrast, COPD is a relatively unknown condition—even the name causes confusion—with no public story to which patients can relate. As such patients often have no expectation of death and no despair, and equally no hope of cure.

Comparison with other illness trajectories

Our findings raise interesting comparisons with other disease trajectories. COPD has a lifelong trajectory (effectively from the first exposure to cigarette smoke, which may be in utero),39 and the onset of symptoms is so insidious as to be imperceptible. In contrast, despite their chronic nature, most other types of long term organ failure typically have a relatively acute presentation (for example, myocardial infarction may present as heart failure).

Another comparator might be patients who have congenital conditions. The concept of “continual biographical revision” has been used to describe how young people with cystic fibrosis attempt to normalise their lives,40 although the genetic cause of this disease and its impact during childhood distinguishes it from COPD. Morbid obesity, which is caused by lifestyle, may be a parallel health problem that is not an illness. The poorly understood disease trajectory of the frail elderly echoes recent understanding of accelerated lung ageing in smokers,41 and the biomedical model of decline in lung function,39 and may resonate best with the disease trajectory of COPD.

Strengths and limitations of study

Our 21 participants may not fully represent the diversity of people with very severe COPD. In particular, none was from an ethnic minority background, although the study cohort encompassed a broad range of demographic, social, clinical, and healthcare backgrounds. All our participants were smokers or ex-smokers, reflecting the profile of COPD in the UK, and it cannot be assumed that their attitudes can be extrapolated to non-smokers. However, the causal link of COPD with lifestyle factors described by our participants encompassed environmental exposure to a broad range of pollutants as well as smoking. Interviewing patients and informal carers together may have resulted in perspectives being modified or withheld; our experienced researcher was aware of this potential problem and could adopt strategies to enable independent voices to be heard.20 We were aware that researchers’ attitudes influence design, data collection, and analysis of qualitative studies, and used our multidisciplinary professional team and lay advisers to ensure balanced interpretation of the data.22 In addition, the comments of the delegates at the end of the study workshop added to our understanding of the emerging themes and their practical and policy implications.

Conclusions and policy implications

Our findings challenge current assumptions about models of care and have two important implications for clinicians and policy makers. Firstly, our findings suggest that, in contrast to other conditions, COPD is perceived as “a way of life” rather than an illness that disrupts life. This may underpin acceptance of and adaptation to increasing disability and major health and social needs, in a lifestyle that has become familiar over many years to patients, informal carers, and professional carers. Recognition by healthcare professionals of the risk of “passive acceptance” may enable services to be developed that actively identify and seek to address needs.

Secondly, current models of palliative care for non-malignant disease, adapted from the traditional cancer model, are predicated on an ability to identify “palliative” patients whose end of life care needs should then be assessed and addressed (and who in some systems should eschew curative care3).2 Our data suggest that a point of transition to palliative care is meaningless and impractical in COPD, a condition with no coherent story and an unanticipated end. Linking palliation of symptoms and supportive care to identifying a point of transition thus risks “prognostic paralysis.”8

We therefore propose linking holistic assessments of supportive and palliative care needs with milestones throughout the patient’s journey. Suitable milestones might be diagnosis, retirement on medical grounds, starting long term oxygen therapy, hospital admission for an exacerbation of COPD, or (from a clinicians’ perspective) a positive answer to the “surprise” question.8 The palliative care approach thus becomes progressively integrated with good care of a lifelong progressive disabling condition, with palliative care specialists available to advise on management of intractable symptoms (especially breathlessness). The historically low profile of COPD and its lack of public story is a further barrier to effective provision of supportive care. Voluntary organisations may choose to champion the disease and communicate a story to aid public understanding of this silent, lifelong, progressively disabling condition.

What is already known on this topic

The needs of people with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are poorly addressed, despite the recognised burden of disabling physical symptoms, psychological distress, and social isolation

Policy makers are extrapolating to patients with COPD models of palliative care designed for people dying from cancer, in whom a transition point to a terminal phase can be relatively easily identified

What this study adds

In contrast with many other long term conditions, COPD is perceived by patients and their informal carers as a “way of life”

Patients with COPD tell a “story” of a health problem with no clear beginning, that is indistinguishable from their life story, and with an unpredictable and unanticipated end

Clinicians may need to use a proactive management strategy in patients with COPD to minimise the risk of suboptimal management associated with patient and carer inertia.

Rather than looking for a transition point to switch to a palliative care approach, holistic assessments of needs could be linked with milestones throughout the patient’s journey (such as a hospital admission or retirement on medical grounds), which would progressively integrate supportive care into the good care for people with COPD

We are grateful to Janet Winter, Colette Lamb, and Anne Aitken, who undertook the initial clinical assessments, and to Marie Pitkethly, Colette Fulton, and June McGill, from Scottish Primary Care Research Network, who helped with recruitment. Susan Buckingham provided administrative support, and David Chinn assisted with coordination of the project within the work of the Primary Palliative Care Research Group. We thank the members of the lay advisory group, recruited by Wendy Halley from the local British Lung Foundation Breathe Easy groups, who worked with us throughout the study, and Patrick White, Declan Cawley, and Tony Davison for their perceptive comments on our draft manuscript.

Contributors: HP initiated the idea for the study and led development of the protocol, securing of funding, study administration, data analysis, interpretation of results, and writing of the paper. MK undertook all the data collection and analysis. All authors had full access to all the data and were involved in interpretation of the data. HP and MK wrote the initial draft of the paper, to which all the authors contributed. HP and MK are study guarantors.

Funding: This study was supported by the Chief Scientist’s Office of the Scottish Government. HP is supported by a primary care research career award from the Chief Scientist’s Office of the Scottish Government.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval was provided by the Multicentre Research Ethics Committee for Scotland (B), and governance approval was obtained from NHS Lothian, NHS Tayside and NHS Forth Valley. Informed written consent was obtained from all patients at the beginning of the study and reviewed verbally before each interview. Informal and professional carers identified by the patient were asked independently for their consent to participate.

Data sharing: We do not have consent to share data.

Cite this as: BMJ 2011;342:d142

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Appendix 1 Topic guides

Appendix 2 Initial coding framework

Appendix 3 The national workshop

Appendix 4 Lay advisory group

References

- 1.Mannino DM, Buist AS. Global burden of COPD: risk factors, prevalence, and future trends. Lancet 2007;370:765-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NHS End of Life Care Programme. The gold standards framework. 2010. www.goldstandardsframework.nhs.uk.

- 3.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Publication no 02154: a special way of caring for people who are terminally ill. US Department of Health and Human Services, 2008.

- 4.Department of Health. NHS end of life care strategy: promoting high quality care for all adults at the end of life. Department of Health, 2008.

- 5.World Health Organization. The solid facts: palliative care. WHO, 2004.

- 6.Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Sheikh A. Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ 2005;330:1007-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coventry PA, Grande GE, Richards DA, Todd CJ. Prediction of appropriate timing of palliative care for older adults with non-malignant life-threatening disease: a systematic review. Age Ageing 2005;34:218-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray SA, Boyd K, Sheikh A. Palliative care in chronic illness. We need to move from prognostic paralysis to active total care. BMJ 2005;330:611-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Connors AF, Dawson NV, Thomas C, Harrell F, Desbiens N, Fulkerson WJ, et al. Outcomes following acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive lung disease. The SUPPORT investigators. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;154:959-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Almagro P, Calbo E, de Echagüen AO, Quintana BBS, Heredia JL, Garau J. Mortality after hospitalization for COPD. Chest 2002;121;1441-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Christakis NA, Escarce JJ. Survival of Medicare patients after enrollment in hospice programs. N Eng J Med 1996;335:172-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christakis NA, Lamont EB. Extent and determinants of error in doctor’s prognosis in terminally ill patients: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2000;320:469-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gore JM, Brophy CJ, Greenstone MA. How well do we care for patients with end stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)? A comparison of palliative care and quality of life in COPD and lung cancer. Thorax 2000;55:1000-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Habraken JM, Willems DL, de Kort SJ, Bindels PJE. Health care needs in end-stage COPD: a structured literature review. Pat Ed Counsel 2007;68:121-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rocker GM, Sinuff T, Horton R, Hernandez P. Advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: innovative approaches to palliation. J Palliat Med 2007;10:783-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seamark DA, Seamark CJ, Halpin D. Palliative care in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a review for clinicians. J R Soc Med 2007;100:225-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lynn J, Ely EW, Zhong Z, McNiff KL, Dawson NV, Connors A, et al. Living and dying with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Am Geriatrics Soc 2000;48(suppl 5):S91-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Department of Health. Consultation on a strategy for services for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in England. Department of Health, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.NHS Quality Improvement Scotland. Clinical standards for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease services. NHS Scotland, 2010.

- 20.Kendall M, Murray SA, Carduff E, Worth A, Harris F, Lloyd A, et al. Use of multiperspective qualitative interviews to understand patients’ and carers’ beliefs, experiences, and needs. BMJ 2009;339:b4122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murray S, Sheikh A. Serial interviews for patients with progressive diseases. Lancet 2006;368:901-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malterud K, Qualitative research: standards, challenges and guidelines. Lancet 2001;358:483-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reissman CK, Narrative analysis. Sage, 1993.

- 24.Bury M. Chronic illness as biographical disruption. Sociology Health Illness 1982;4:167-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frank A. The wounded storyteller: body, illness and ethics. University of Chicago Press, 1995.

- 26.Murray SA, Boyd K, Kendall M, Worth A, Benton TF, Clausen H. Dying of lung cancer or cardiac failure: prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers in the community. BMJ 2002;325:929-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seymour JE, French J, Richardson E. Dying matters: let’s talk about it. BMJ 2010;341:c4860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elofsson LC, Ohlen J. Meanings of being old and living with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Palliat Med 2004;18:611-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Exley C, Field D, Jones L, Stokes T. Palliative care in the community for cancer and end-stage cardiorespiratory disease: the views of patients, lay-carers and health care professionals. Palliat Med 2005;19:76-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sprangers MA, Schwartz CE. Integrating response shift into health-related quality of life research: a theoretical model. Soc Sci Med 1999;48:1507-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Habraken JM, Pols J, Bindels PJE, Willems DL. The silence of patients with end-stage COPD: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract 2008;58:844-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cornwell J. Hard earned lives: accounts of health and illness from East London. Tavistock, 1984.

- 33.Charmaz K. Loss of self: a fundamental form of suffering in the chronically ill. Sociology Health Illness 1983;5:168-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams G. The genesis of chronic illness: narrative reconstruction. Sociology Health Illness 1984;6:175-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams SJ. Chronic illness as biographical disruption or biographical disruption as chronic illness? Reflections on a core concept. Sociology Health Illness 2000;22:40-67. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanders C, Donovan J, Dieppe P. The significance and consequences of having painful and disabled joints in older age: co-existing accounts of normal and disrupted biographies. Sociology Health Illness 2002;24:227-53. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pound P, Gompertz P, Ebrahim S. Illness in the context of older age: the case of stroke. Sociology Health Illness 1998;20:489-506. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diffen E. Is the ‘Jade effect’ still working? BBC News, 2010. March 22. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/magazine/8579781.stm.

- 39.Fletcher C, Peto R. The natural history of chronic airflow obstruction. BMJ 1977;1:1645-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams B, Corlett J, Dowell JS, Coyle J, Mukhopadhyay S. “I’ve never not had it so I don’t really know what it’s like not to”: nondifference and biographical disruption among children and young people with cystic fibrosis. Qual Health Res 2009;19:1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ito K, Barnes PJ. COPD as a disease of accelerated lung aging. Chest 2009;135:173-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1 Topic guides

Appendix 2 Initial coding framework

Appendix 3 The national workshop

Appendix 4 Lay advisory group