Abstract

Background and Aims

Cleomaceae is one of 19 angiosperm families in which C4 photosynthesis has been reported. The aim of the study was to determine the type, and diversity, of structural and functional forms of C4 in genus Cleome.

Methods

Plants of Cleome species were grown from seeds, and leaves were subjected to carbon isotope analysis, light and scanning electron microscopy, western blot analysis of proteins, and in situ immunolocalization for ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase oxygenase (Rubisco) and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC).

Key Results

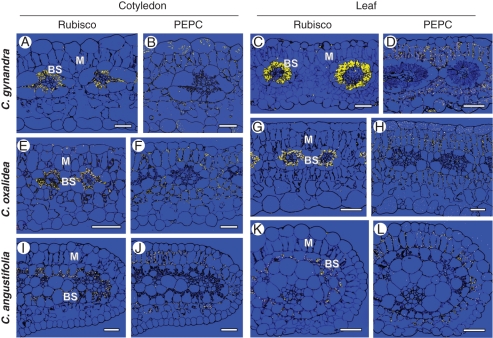

Three species with C4-type carbon isotope values occurring in separate lineages in the genus (Cleome angustifolia, C. gynandra and C. oxalidea) were shown to have features of C4 photosynthesis in leaves and cotyledons. Immunolocalization studies show that PEPC is localized in mesophyll (M) cells and Rubisco is selectively localized in bundle sheath (BS) cells in leaves and cotyledons, characteristic of species with Kranz anatomy. Analyses of leaves for key photosynthetic enzymes show they have high expression of markers for the C4 cycle (compared with the C3–C4 intermediate C. paradoxa and the C3 species C. africana). All three are biochemically NAD-malic enzyme sub-type, with higher granal development in BS than in M chloroplasts, characteristic of this biochemical sub-type. Cleome gynandra and C. oxalidea have atriplicoid-type Kranz anatomy with multiple simple Kranz units around individual veins. However, C. angustifolia anatomy is represented by a double layer of concentric chlorenchyma forming a single compound Kranz unit by surrounding all the vascular bundles and water storage cells.

Conclusions

NAD-malic enzyme-type C4 photosynthesis evolved multiple times in the family Cleomaceae, twice with atriplicoid-type anatomy in compound leaves having flat, broad leaflets in the pantropical species C. gynandra and the Australian species C. oxalidea, and once by forming a single Kranz unit in compound leaves with semi-terete leaflets in the African species C. angustifolia. The leaf morphology of C. angustifolia, which is similar to that of the sister, C3–C4 intermediate African species C. paradoxa, suggests adaptation of this lineage to arid environments, which is supported by biogeographical information.

Keywords: C3 plants, C4 plants, chloroplast ultrastructure, Cleome, Cleomaceae, immunolocalization, leaf anatomy, NAD-malic enzyme type, photosynthetic enzymes

INTRODUCTION

In certain conditions, photosynthesis in C3 plants can become CO2 limited, resulting in increased photorespiration. Ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase oxygenase (Rubisco) is a bifunctional enzyme that catalyses fixation of CO2 during photosynthesis and fixation of O2, which leads to photorespiration. High temperatures decrease both the specificity of Rubisco to function as a carboxylase and the solubility of CO2 in photosynthetic tissue, while limiting availability of water reduces stomatal conductance of CO2 into leaves. In C3 plants, there is direct fixation of atmospheric CO2 via Rubisco in chloroplast-containing mesophyll (M) tissues. C4 plants have a mechanism which concentrates CO2 around Rubisco and represses photorespiration. This occurs in most C4 plants through a dual chlorenchyma cell system called Kranz anatomy, consisting of M and bundle sheath (BS) cells. Atmospheric CO2 is captured in M cells via phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC) with formation of C4 acids, which then act as donors of CO2 via C4 acid decarboxylases to Rubisco in chloroplasts of BS cells (Edwards and Walker, 1983; Hatch, 1987; Kanai and Edwards, 1999; Sage, 2004).

Species having C4 photosynthesis have been found in 19 plant families; they are considered to have evolved independently from C3 plants >50 times in response to limiting availability of CO2 (Sage, 2004). This has resulted in substantial biochemical and structural diversity in the forms of C4, and this information is being utilized in phylogenetic studies on the origins of C4 (Kadereit et al., 2003; Kapralov et al., 2006; Sage et al., 2007; Besnard et al., 2009; Christin et al., 2009; Raghavendra and Sage, 2011).

In Kranz anatomy the outer layer of chlorenchyma cells is represented by palisade M cells and the inner layer by rounded BS (or Kranz) cells; they either surround individual veins, resulting in multiple simple Kranz units, or enclose several or all the veins, forming a compound Kranz unit, according to the classification portrayal by Peter and Katinas (2003). In both cases, various structural forms have been characterized in a number of families, showing the vast biological diversity in evolution of the C4 syndrome (Brown, 1975; Carolin et al., 1975, 1978; Dengler and Nelson, 1999; Peter and Katinas, 2003; Muhaidat et al., 2007; Edwards and Voznesenskaya, 2011). A number of characteristics are taken into account to distinguish between different structural sub-types, and in classification of biochemical sub-types. These include positioning of chlorenchyma layers with respect to vascular bundles and other tissues, positioning of veins and organelles in BS cells, the occurrence and distribution of different types of tissues in the leaf (e.g. mestome sheath in monocots, hypodermal or water storage cells in eudicots), and organelle (chloroplast and mitochondria) differentiation between M and BS cells.

There are three biochemical subtypes based on the main C4 acid decarboxylase employed, i.e. NADP-malic enzyme (NADP-ME) and NAD-malic enzyme (NAD-ME), which are found in both monocot and eudicot species, and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEP-CK) found in grasses. With respect to organelle structure, in all C4 monocot and eudicot species, BS cells in NADP-ME species have grana-deficient chloroplasts and a few, small mitochondria, while BS cells in NAD-ME species contain chloroplasts with well-developed grana and numerous large mitochondria (Dengler and Nelson, 1999; Edwards et al., 2007; Edwards and Voznesenskaya, 2011). The degree of chloroplast differentiation between two chlorenchyma cells can be shown by calculation of the ‘granal index’, which gives the percentage of the stacked thylakoids in relation to the length of all thylakoids in chloroplasts (Lichtenthaler et al., 1982). Early studies indicate that the degree of grana development in BS chloroplasts in C4 species correlates with the capacity for photosystem II (PSII) activity, linear electron flow and capacity for generation of NADPH, with low grana-containing chloroplasts being deficient in PSII and richer in PSI-mediated cyclic electron flow producing ATP (Edwards and Walker, 1983; see also Anderson, 1999). Thus, differences in grana development are considered to be associated with differences between M and BS cells in the need for NADPH relative to ATP to support C4 photosynthesis. A higher degree of grana development in BS compared with M chloroplasts is typical for species of the NAD-ME biochemical sub-group (Gamaley, 1985; Voznesenskaya and Gamaley, 1986; Voznesenskaya et al., 1999; Edwards et al., 2004; Edwards and Voznesenskaya, 2011). The M chloroplasts are considered to have a lower requirement for production of reductive power, since only ATP is needed to support an aspartate-type C4 cycle (Edwards and Walker, 1983; Voznesenskaya et al., 1999).

According to some classifications, the genus Cleome sensu lato (family Cleomaceae) includes >200 species which are pantropical in distribution and conspicuous in tropical, seasonally dry habitats (Hall et al., 2002; Sanchez-Acebo, 2005). It has long been known that one species, Cleome gynandra, is C4, since Sankhla et al. (1975) reported it has Kranz anatomy and a C4-type carbon isotope composition (δ13C). Recently, two other species, C. angustifolia and C. oxalidea, were suggested to be C4 plants based on C4/Crassulacean acid metabolism-type δ13C values of herbarium specimens (Marshall et al., 2007; Voznesenskaya et al., 2007a). Also one species, C. paradoxa, was identified as a C3–C4 intermediate based on its intermediate CO2 compensation point (27·5 µmol mol−1), leaf anatomy and ultrastructural features, and selective localization of glycine decarboxylase of the photorespiratory pathway in mitochondria of BS cells (Voznesenskaya et al., 2007a). Further studies of leaf anatomy in representative species of the genus Cleome showed that many C3 species have increased venation in leaves, and several species have both increased venation and enlarged BS cells; these features can be considered developmental progressions from C3 to C4 photosynthesis (Marshall et al., 2007). Besides interest in determining the occurrence, diversity and evolution of C4 in family Cleomaceae, there is interest in developing the C4 species C. gynandra as a model system (Brown et al., 2005; Newell et al., 2010) since, among families having C4, Cleomaceae is most closely related to family Brassicaceae, in which Arabidopsis occurs (the well-known model plant with C3-type photosynthesis). This would allow comparisons of genomes and molecular analyses between the two in efforts to identify the genes required for development of C4 photosynthesis.

The objectives of this study were to establish if C. oxalidea and C. angustifolia, along with C. gynandra, are C4 species, and to determine the degree of structural and biochemical diversity in photosynthesis in leaves and cotyledons of these species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material

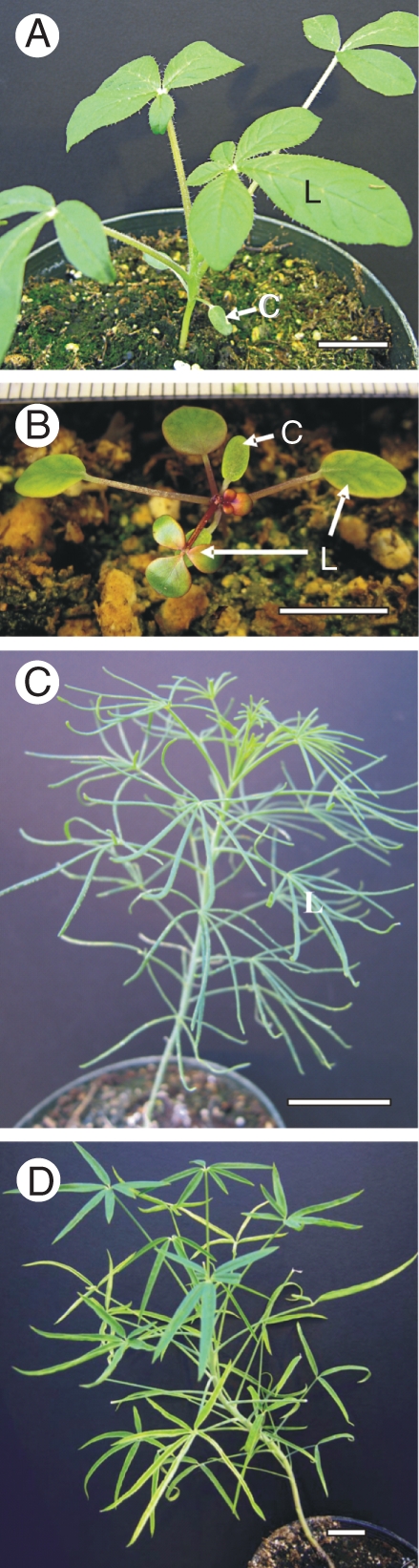

Information about the source of seeds and voucher specimens is given in Table 1. All seeds were stored at 3–5 °C prior to use and were germinated on moist paper in Petri dishes at room temperature and a photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) of 20 µmol quanta m−2 s−1. The seedlings were then transplanted to 10 or 15 cm diameter pots with commercial potting soil and grown in the Washington State University (WSU) greenhouse during the mid-winter/spring months, with an approx. 26 °C day/18 °C night thermoperiod. Maximum midday PPFD was 1200 µmol quanta m−2 s−1 on clear days. For microscopy and biochemical analyses, samples of mature cotyledons were taken from plants with at least 2–4 leaves; mature, fully expanded leaves were taken from plants approx. 4–6 weeks old (3–5 samples were taken from 2–3 different plants in both cases). All Cleome species studied are annual herbs. In nature, mature plants of C. gynandra, C. angustifolia and C. paradoxa can reach a height up to 1 m (Hooker, 1875; Oliver, 1868; Elffers et al., 1964). The African species C. africana is usually up to 0·5 m tall (Post, 1896), while the Australian endemic C. oxalidea is the only known rosette species, and has a height with bolting and floral development of only 5–15 cm (Hewson, 1982; http://florabase.calm.wa.gov.au/). A general view of plants grown in the WSU greenhouse is shown in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Source of Cleome seeds and voucher specimen references at the Marion Ownbey Herbarium, Washington State University

| Species | Source of seeds | Origin of seeds | Voucher specimens |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. gynandra L. | Kindly provided by Dr A. S. Raghavendra | Collected in Hyderabad, India | WS 369765 |

| C. oxalidea F. Muell. | Kindly provided by Dr Lyndley Craven | Collected from North-Western Australia | WS 369811 |

| C. angustifolia Forssk. | From herbarium material kindly provided by Drs A. Oskolskii and O. Maurin | Collected by Dr. O. Maurin in Kruger National Park, South Africa | WS 375818 |

| C. paradoxa R. Br. ex DC. | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, #0109051 | Yemen | WS 369807 |

| C. africana Botsch. | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, #0142768 | Egypt | WS 369771 |

Fig. 1.

General views of plants of (A) C. gynandra, (B) C. oxalidea, (C) C. angustifolia and (D) C. paradoxa. C, cotyledon; L, leaf. Scale bars: (A, C, D) = 2 cm, (B) = 1 cm.

Carbon isotope composition

δ13C values, a measure of the carbon isotope composition, were determined at WSU on leaf samples taken from plants using a standard procedure relative to PDB (Pee Dee Belemnite) limestone as the carbon isotope standard (Bender et al., 1973). Plant samples were dried at 60 °C for 24 h, milled to a fine powder, and then 1–2 mg were placed into a tin capsule and combusted in a Eurovector elemental analyser. The resulting N2 and CO2 gases were separated by gas chromatography and admitted into the inlet of a Micromass Isoprime isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS) for determination of 13C/12C ratios. δ13C values were determined: δ13C = [(Rsample/Rstandard) –1] × 1000, where δ13C is an expression of the 13C/12C of the plant sample relative to the standard (reported in parts per 1000), and Rsample and Rstandard are the 13C/12C ratio of the plant sample and the PDB limestone, respectively.

Light and electron microscopy

Samples for structural studies (3–5 pieces of leaves and cotyledons from 2–3 separate individuals for each species) were fixed at 4 °C in 2 % (v/v) paraformaldehyde and 2 % (v/v) glutaraldehyde in 0·1 m phosphate buffer (pH 7·2), post-fixed in 2 % (w/v) OsO4 and then, after a standard acetone dehydration procedure, embedded in Spurr's epoxy resin. Cross- and paradermal sections were made on a Reichert Ultracut R ultramicrotome (Reichert-Jung GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany). For light microscopy, semi-thin sections 0·8–1 µm thick were stained with 1 % (w/v) toluidine blue O in 1 % (w/v) Na2B4O7, and studied under an Olympus BH-2 (Olympus Optical Co., Ltd) light microscope equipped with an LM Digital Camera & Software (Jenoptik ProgRes Camera, C12plus, Jena, Germany). Ultra-thin sections (about 70–90 nm thick) were stained for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) with 4 % (w/v) uranyl acetate followed by 2 % (w/v) lead citrate. The transmission electron microscopes used for observation and photography were Hitachi H-600 (Hitachi, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) and JEOL JEM-1200 EX (JEOL USA, Inc., Peabody, MA, USA) equipped with a MegaView III Digital Camera and Soft Imaging System Corp. software (Lakewood, CO, USA). The granal index was calculated as the percentage of the length of appressed thylakoid membranes with reference to the total length of all thylakoid membranes in a chloroplast (Lichtenthaler et al., 1982). The lengths of non-appressed thylakoid membranes included the length of both intergranal and end granal membranes, i.e. all membranes exposed to the stroma. Measurements were made with a curvimeter Ku-A (Map Measure Meter, Russia) on micrographs on at least ten median chloroplast sections. Thylakoid density was calculated as the length of thylakoid membranes (in μm) per μm2 of chloroplast area (total stroma and thylakoid area of the chloroplast, excluding starch grains). The chloroplast area was estimated on the same micrographs using an image analysis program (UTHSCSA, Image Tool for Windows, version 3·00). The thickness of M and BS cell walls and sizes of mitochondria were measured on 15–25 TEM micrographs using the same image analysis program.

Leaf venation

Paradermal semi-thin sections (1 µm thick) of C. gynandra, C. oxalidea, C. paradoxa and C. africana leaves fixed for study by light microscopy (see the previous section) were used for observing vein density and pattern of venation. One to two leaf samples from two different plants were sectioned for this purpose. This method gives a clear picture of cell and organelle distribution in leaf but can be used only for flat leaf blades with veins distributed in one plane. To observe venation in all species studied, and especially in terete leaves of C. angustifolia which are oval in cross-sections, whole leaves (at least 3–5 from two different plants) were cleared in 70 % ethanol (v/v) until chlorophyll was removed, bleached with 5 % (w/v) NaOH overnight, and rinsed three times in water. The leaves were mounted in water and examined under UV light [with a 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) filter] on a Leica DMFSA fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems Wetzlar GmbH, Germany) using autofluorescence of lignified xylem vessels.

Western blot analysis

Proteins were extracted from leaves by homogenizing 0·2 g of tissue in 0·5 mL of extraction buffer [100 mm Tris–HCl, pH 7·5, 10 mm (w/v) MgCl2, 1 mm (w/v) EDTA, 15 mm (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol, 20 % (v/v) glycerol and 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride]. After centrifugation at 10 000 g for 10 min in a microcentrifuge, the supernatant was collected and the protein concentration was determined with Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad) using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard. The supernatant fraction was diluted 1:1 in 60 mm Tris–HCl, pH 7·5, 4 % (w/v) SDS, 20 % (v/v) glycerol, 0·5 % (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol and 0·1 % (w/v) bromphenol blue, and boiled for 5 min for SDS–PAGE. Protein samples (20 µg) were separated by 10 % SDS–PAGE, blotted onto nitrocellulose and probed overnight at 4 °C with anti-Amaranthus hypochondriacus NAD-ME IgG which was prepared against the 65 kDa α-subunit, courtesy of J. Berry (Long and Berry, 1996) (1:2000), anti-Zea mays 62 kDa NADP-ME IgG, courtesy of C. Andreo (Maurino et al., 1996) (1:2500), anti-Z. mays PEPC IgG (Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA) (1:20 000), anti-Z. mays pyruvate,Pi dikinase (PPDK) IgG, courtesy of T. Sugiyama (1:20 000), anti-Nicotiana tabacum Rubisco (large subunit) IgG, courtesy of R. Chollet (1:10,000) or anti-Urochloa maxima PEP-CK, courtesy of R. Walker (1:5000). Goat anti-rabbit IgG–alkaline phosphatase conjugate antibody (Bio-Rad) was used at a dilution of 1:50 000 for detection. Bound antibodies were localized by developing the blots with 20 mm nitroblue tetrazolium and 75 mm 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate in the detection buffer (100 µm Tris–HCl, pH 9·5, 100 mm NaCl, 5 µm MgCl2). As controls for NADP-ME and PEP-CK biochemical types, protein extracts from leaves of Eriachne aristidea F. Muell. and Spartina anglica C.E. Hubb. were used, respectively.

In situ immunolocalization

Leaf samples were fixed at 4 °C in 2 % (v/v) paraformaldehyde and 1·25 % (v/v) glutaraldehyde in 0·05 m PIPES buffer, pH 7·2. The samples were dehydrated with a graded ethanol series and embedded in London Resin White (LR White, Electron Microscopy Sciences, Fort Washington, PA, USA) acrylic resin. Antibodies used (all raised in rabbit) were anti-N. tabacum Rubisco (large subunit) IgG, courtesy of R. Chollet, and commercially available anti-Z. mays L. PEPC IgG (Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA). Pre-immune serum was used in all cases for controls.

Leaf cross-sections, 0·8–1 µm thick, were dried from a drop of water onto gelatin-coated slides and blocked for 1 h with TBST + BSA [10 mm Tris–HCl, 150 mm NaCl, 0·1 % (v/v) Tween-20, 1 % (w/v) BSA, pH 7·2]. They were then incubated for 3 h with either pre-immune serum diluted in TBST + BSA (1:100 dilution), anti-Rubisco (1:50) or anti-PEPC (1:200). The slides were washed with TBST + BSA and then treated for 1 h with 10 nm protein A–gold (diluted 1:100 with TBST + BSA). After washing, the sections were exposed to a silver enhancement reagent for 20 min according to the manufacturer's directions (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL, USA), stained with 0·5 % (w/v) Safranin O and imaged in a reflected/transmitted mode using a Zeiss Confocal LSM 510 Meta Laser Scanning Microscope (Carl Zeiss, Inc., Thornwood, NY, USA). The background labelling with pre-immune serum was very low, although occasional labelling occurred in areas where the sections were wrinkled due to trapping of antibodies/label (results not shown).

Statistical analysis

Where indicated, standard errors were determined, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed with Statistica 7·0 software (StatSoft, Inc.). Tukey's HSD (honest significant difference) tests were used to analyse differences between species and different cell types in terms of cell wall thickness, mitochondrial sizes and the chloroplast thylakoid system. All analyses were performed at the 95 % significance level.

RESULTS

Carbon isotope composition

Leaves of C. gynandra, C. oxalidea and C. angustifolia from greenhouse-grown plants, like herbarium specimens collected from natural habitats, had C4-type δ13C values. Values of C. gynandra and C. oxalidea were slightly more negative in comparison with previous analyses with field samples, but still within the range of C4 plants. Much more negative, C3-type values were observed in the C3–C4 intermediate species C. paradoxa and the C3 species C. africana (see also Voznesenskaya et al., 2007a) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Carbon isotope composition (δ13C) of leaves of representative Cleome species from greenhouse-grown plants vs. herbarium specimens.

| δ13C (°/oo) values |

||

|---|---|---|

| Species | Greenhouse-grown specimens* | Herbarium specimens |

| C. gynandra | –15·9 | –12·3†; –14·1†; –13·9‡ |

| C. oxalidea | –16·4 | –14·6†; –15·8†; –14·1‡ |

| C. angustifolia | –14·1 | –12·5†; –13·4†; –14·4§; –12·9‡ |

| C. paradoxa | –26·0† | –23·8† |

| C. africana | –30·1† | –25·7† |

* For greenhouse-grown material, n = 2.

§ Collected by Dr O. Maurin in Kruger National Park, South Africa, April, 2007.

Morphology, anatomy and venation

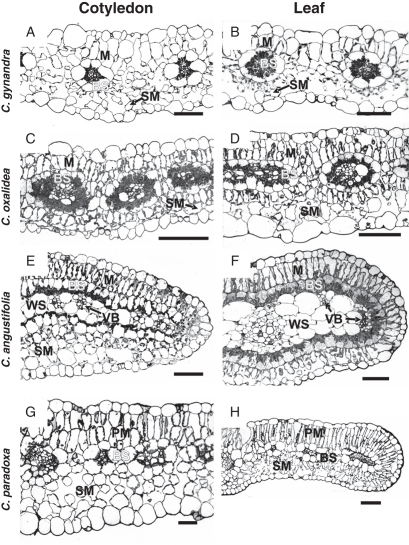

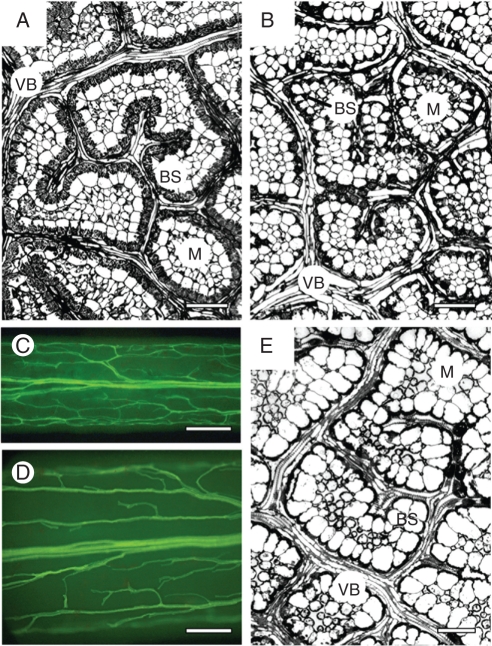

Cleome gynandra, previously the only documented C4 species in the genus, has approx. 1 cm long, oblong cotyledons and palmately compound leaves with up to five flat, broad leaflets (Fig. 1A). Greenhouse-grown plants reach a height of approx. 0·5 m (not shown). Leaves and cotyledons have a similar atriplicoid-type Kranz anatomy with two concentric layers of chlorenchyma cells (M and BS) around each lateral vascular bundle (VB); BS cells have organelles in the centripetal position (Fig. 2A, B). There is one layer of rather loosely arranged, palisade M cells on the adaxial side of the blades, while M cells adjacent to the BS cells on the abaxial side have the appearance of small, spongy parenchyma cells; also, a discontinuous hypodermal layer of spongy mesophyll is present on the abaxial side (Fig. 2A, B). A paradermal section of the leaf of this species (as well as results obtained from study of leaf clearings; not shown) shows a high density and close positioning of VBs: the numbers of M cells between BS cells of the neighbouring veins ranges from one to four (Fig. 3A; also see Voznesenskaya et al., 2007a).

Fig. 2.

General anatomy of cotyledons (A, C, E, G) and leaves (B, D, F, H) of three C4 Cleome species and the C3–C4 intermediate C. paradoxa. (A, B) C. gynandra and (C, D) C. oxalidea having atriplicoid type of anatomy in leaves and cotyledons, with multiple simple Kranz units. (E, F) C. angustifolia having different types of anatomy with single compound Kranz units in cotyledons (Kranz chlorenchyma surrounds veins distributed in the lateral plane; two additional layers of spongy mesophyll on the abaxial side) and leaves (Kranz chlorenchyma forms a continuous layer around the leaf periphery, enclosing water storage tissue and vascular bundles). (G, H) C. paradoxa with a clearly dorsiventral type of anatomy in leaves and cotyledons. BS, bundle sheath cells; M, mesophyll cells in species with Kranz anatomy; PM, palisade mesophyll; SM, spongy mesophyll; VB, vascular bundle; WS, water storage tissue. Scale bars: (A, B, E–G) = 100 µm, (C, D, H) = 50 µm.

Fig. 3.

Illustration of the venation pattern and leaf vein density on leaf paradermal sections for (A) C. gynandra, (B) C. oxalidea and (E) C. paradoxa and by leaf clearing for (C, D) C. angustifolia at lower (C) and higher (D) magnifications. Paradermal sections show close positioning of veins surrounded by bundle sheath cells with centripetally located organelles. Observation of cleared leaves of C. angustifolia (C, D) under UV light shows venation is not highly branched, and there is a cluster of veins in the marginal position. BS, bundle sheath cells; M, mesophyll cells; VB, vascular bundle. Scale bars: (A, B, E) = 25 µm, (C) = 500 µm, (D) = 250 µm.

Cleome oxalidea is a small plant with rosette leaves. After 1 month of growth in the greenhouse, plant rosettes were about 3 cm in diameter. Cotyledons were approx. 0·5 cm long and approx. 0·2 cm wide, and the first leaves were simple, rounded and approx. 0·6–0·8 cm in diameter, but, beginning with the fourth leaf, they were trifoliate (Fig. 1B). Both cotyledons and leaves have Kranz anatomy of the atriplicoid type, with palisade M cells around BS cells on both sides of the blade, and a sub-epidermal layer of spongy parenchyma cells on the abaxial side (Fig. 2C, D); however, the cotyledons have one layer of palisade M cells on the adaxial side while in leaves there are one or two layers. In contrast to C. gynandra, there is an even distribution of palisade M cells around BS cells. In both leaves and cotyledons, the large BS cells contain numerous organelles in a centripetal position (Fig. 2C, D).

Cleome angustifolia is a large plant, growing up to 1·0 m in the greenhouse (not shown). It has elongated, narrow cotyledons (0·8–1·5 cm long and 0·2–0·3 cm wide) and palmately compound leaves with 5–8 narrow leaflets (Fig. 1C). This species was found to have Kranz anatomy with two chlorenchyma layers, M and BS cells, distributed on the leaf periphery and enclosing the VBs and water storage tissue in both cotyledons and leaves (Fig. 2E, F). There are distinct structural differences between the two.

In cotyledons, there is one layer of palisade M cells on the adaxial side of the blade, while on the abaxial side the M layer consists of rather small rounded cells. In addition, there are two layers of rounded spongy parenchyma cells on the abaxial side of the cotyledon (Fig. 2E). The VBs are distributed in the lateral plane. The xylem of the VB is always in contact with the BS cells on the adaxial side of the cotyledon. On the abaxial side, the phloem of the VBs is rather often in contact with the BS layer; but, in some cases VBs are separated from BS cells by small water storage cells. Bundle sheath cells in both positions have organelles distributed centripetally, but their concentration is higher on the adaxial side.

In semi-terete, fleshy leaves of C. angustifolia, cross-sections show that the M cells are more loosely arranged on the abaxial side; and, in contrast to the cotyledons, there are no additional layers of spongy parenchyma (Fig. 2F). The middle part of the leaf contains water storage tissue, with the main vein in the centre of the leaf blade and the smaller VBs arranged internally to the BS layer on the adaxial or lateral sides of the leaf, and they are always in contact with BS cells from the xylem side (Fig. 2F). Serial sections showed that the lateral VBs extend from the main vein almost directly to the adaxial side of the leaf. A study of cleared leaves of C. angustifolia shows the central positioning of the main vein with a somewhat rare anastomosing net of a few lateral VBs compared to the dense net of veins which occur in different orders in species with atriplicoid-type anatomy (Fig. 3C, D). Usually, there is a group of several small veins which form a large cluster of vascular tissue edging the leaf in the most lateral (marginal) position; it runs almost parallel to the main vein from near the base to the tip of the leaf. Organelles in BS cells are distributed centripetally.

Cleome paradoxa is a rather large plant (reaching a height of up to 1 m in greenhouse-grown plants; not shown). Similar to C. angustifolia, it has elongated, narrow cotyledons (0·8–1·0 cm long and approx. 0·1–0·15 cm wide) and palmately compound leaves with 3–6 leaflets which are wider (about 1 cm) and more flattened than in C. angustifolia (Fig. 1D). This species has dorsiventral-type anatomy in both cotyledons and leaves (Fig. 2G, H), with two layers of palisade parenchyma cells on the adaxial side and 2–3 layers of spongy parenchyma on the abaxial side. While it lacks Kranz anatomy, it has enlarged BS cells with a high density of organelles in the centripetal position. Observations on paradermal sections of leaves show that this species has a high vein density and close positioning of VBs, which was also seen in leaf clearings (not shown); there are 1–4 M cells between BS cells of the neighbouring veins (Fig. 3E; also see results on leaves in Voznesenskaya et al., 2007a).

Cleome africana has oblong cotyledons approx. 0·5–0·8 cm long and palmately compound leaves with 3–4 leaflets (Supplementary Data Fig. S1A, available online) and represents an example of a C3 plant with dorsiventral anatomy in cotyledons and leaves. It has three layers of palisade M cells on the adaxial side, and 3–4 layers of spongy M on the abaxial side of the cotyledon and leaf (Fig. S1C, D; for leaf anatomy also see Voznesenskaya et al., 2007a). Like other species in this study having flattened leaves, C. africana has close positioning of veins with 1–3 spongy M cells between VBs, but much larger intercellular air spaces between M cells compared with all the species mentioned above (Fig. S1B; also see Voznesenskaya et al., 2007a).

Electron microscopy

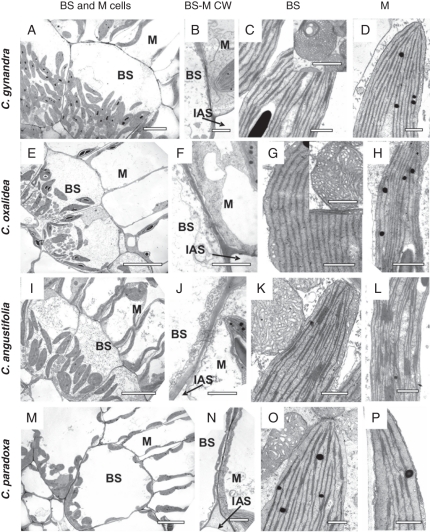

Electron microscopy studies provided detailed views of the positioning of organelles in BS cells of leaves (Fig. 4A, E, I, M) and cotyledons (not shown) of C. gynandra, C. oxalidea, C. angustifolia and C. paradoxa; large mitochondria are located internal to the chloroplasts or between them in the inner part of the cell near the VBs.

Fig. 4.

Electron microscopy of bundle sheath and mesophyll chlorenchyma cells in leaves of (A–D) C. gynandra, (E–H) C. oxalidea, (I–L) C. angustifolia and (M–P) C. paradoxa. (A, E, I, M) Organelles (chloroplasts and numerous mitochondria) in bundle sheath cells are in the centripetal position. (B, F, J, N) Cell walls between bundle sheath and mesophyll cells. (C, G, K, O) Bundle sheath cell mitochondria and chloroplasts. (D, H, L, P) Mesophyll chloroplasts. BS, bundle sheath cells; IAS, intercellular airspace; M, mesophyll cells. Scale bars: (A, E, I, M) = 10 µm, (B, F, J, N) and inserts in (C, B) = 1 µm, (D, H, L, P) = 0·5 µm.

In leaves of C. gynandra, BS cells are about 30–40 µm in diameter (Fig. 4A), and the BS cell wall towards the intercellular air space is five times thicker than that of M cells. Plasmodesmata are distributed in numerous pit fields, with combined M and BS cell wall thickening between them being 3·6 times higher than the thickness of the M cell wall, but lower than the thickness of BS cell walls facing the air spaces (Fig. 4B, Table 3). Both types of chloroplasts, in M and BS, have well-developed grana generally consisting of 3–5 thylakoids (Fig. 4C, D; also see Voznesenskaya et al., 2007a). A comparison of the chloroplast granality in leaves shows that the ratio of granal indices for BS/M chloroplasts is 1·5, with a slightly higher density of appressed thylakoids in BS chloroplasts vs. a higher density of non-appressed thylakoids in M chloroplasts (Table 4). Cotyledons of C. gynandra have a greater difference than leaves in granality between BS and M chloroplasts (BS/M = 2), with BS chloroplasts having 1·6 times higher density of appressed thylakoids, and about 2·5 times lower density of non-appressed thylakoids compared with M chloroplasts. Large BS mitochondria (Table 3; also see Voznesenskaya et al., 2007a) have intensively developed tubular cristae (Fig. 4 C, insert).

Table 3.

Thickness of mesophyll (M) and bundle sheath (BS) cell walls in leaf cross-sections and the sizes of mitochondria in chlorenchyma cells of representative Cleome species

| Thickness of individual cell walls (μm)* |

Diameter of mitochondria (μm)‡ |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Type | M | BS | Combined thickness of cell walls, BS + M (μm)† | M | BS |

| C. gynandra | C4 | 0·08 ± 0·004ab | 0·40 ± 0·03d | 0·29 ± 0·02c | 0·56 ± 0·02c | 0·92 ± 0·02cd |

| C. oxalidea | C4 | 0·11 ± 0·003c | 0·23 ± 0·01b | 0·27 ± 0·01bc | 0·32 ± 0·01a | 0·88 ± 0·03c |

| C. angustifolia | C4 | 0·10 ± 0·012bc | 0·30 ± 0·02c | 0·22 ± 0·01a | 0·47 ± 0·02b | 0·97 ± 0·03d |

| C. paradoxa | C3–C4 | 0·07 ± 0·003a | 0·13 ± 0·01a | 0·20 ± 0·01a | 0·32 ± 0·01a | 0·66 ± 0·01b |

| C. africana | C3 | 0·12 ± 0·003c | 0·13 ± 0·01a | 0·23 ± 0·01ab | 0·40 ± 0·02b | 0·32 ± 0·02a |

Means are from 15–80 measurements ± s.e. Analysis was made by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's HSD (honest significant difference) test. Means followed by a different letter within a column indicate a significant difference between species (P ≤0·05).

* The thickness of individual cell walls was measured on cell walls in contact with the intercellular air space.

† The combined thickness of bundle sheath and mesophyll cell walls was measured at thickened areas between pit fields in areas of contact between two types of chlorenchyma cells.

‡ Measurement was taken at the minor diameter from profiles on cross-sections.

Table 4.

Chloroplast granal index and thylakoid density in palisade mesophyll (M) and bundle sheath (BS) chloroplasts of representative Cleome species

| Appressed thylakoid density‡ |

Non-appressed thylakoid density‡ |

Total thylakoid density‡ |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Organ | Cell type | Granal index (%)† | Length (μm) μm−2 area |

||

| C. gynandra (C4) | Leaf | M | 31·5 ± 3·4* | 16·8 ± 1·7 | 36·6 ± 1·9* | 53·4 ± 0·1 |

| BS | 47·7 ± 1·6 | 21·3 ± 1·8 | 23·6 ± 2·9 | 44·9 ± 4·5 | ||

| Cotyledon | M | 33·2 ± 1·1* | 17·6 ± 0·8* | 35·5 ± 1·0* | 53·1 ± 1·3* | |

| BS | 66·2 ± 1·9 | 27·9 ± 2·3 | 14·4 ± 1·4 | 42·3 ± 3·4 | ||

| C. oxalidea (C4) | Leaf | M | 31·6 ± 1·5* | 16·2 ± 1·0 | 34·7 ± 0·8* | 50·9 ± 1·1* |

| BS | 46·5 ± 0·9 | 18·3 ± 0·9 | 20·8 ± 0·8 | 39·1 ± 1·5 | ||

| Cotyledon | M | 35·7 ± 0·8* | 14·5 ± 0·9 | 26·0 ± 1·8* | 40·5 ± 2·5* | |

| BS | 51·0 ± 0·9 | 15·4 ± 2·0 | 14·7 ± 1·8 | 30·1 ± 3·7 | ||

| C. angustifolia (C4) | Leaf | M | 38·6 ± 1·2* | 18·3 ± 0·9 | 29·1 ± 1·2* | 47·4 ± 1·8* |

| BS | 45·2 ± 2·0 | 19·1 ± 1·0 | 23·2 ± 1·2 | 42·3 ± 1·7 | ||

| Cotyledon** | M | 50·6 ± 1·9 | 22·5 ± 1·2* | 22·4 ± 1·7 | 44·9 ± 2·5 | |

| BS | 48·7 ± 2·4 | 19·2 ± 0·9 | 20·4 ± 1·7 | 39·6 ± 1·2 | ||

| C. paradoxa (C3–C4) | Leaf*** | M | 55·3 ± 1·2 | 17·1 ± 0·9* | 13·8 ± 0·7* | 30·9 ± 1·4* |

| BS | 58·9 ± 0·5 | 27·1 ± 1·5 | 18·9 ± 0·8 | 46·0 ± 2·2 | ||

| Cotyledon | M | 54·0 ± 1·0 | 16·0 ± 1·2 | 13·6 ± 1·0 | 29·6 ± 2·1 | |

| BS | 54·3 ± 1·3 | 13·8 ± 0·7 | 11·8 ± 0·9 | 25·6 ± 1·5 | ||

| C. africana (C3) | Leaf | M | 57·2 ± 0·9 | 14·5 ± 0·7* | 10·8 ± 0·6* | 25·3 ± 1·2* |

| BS | 58·6 ± 0·5 | 18·6 ± 0·8 | 13·2 ± 0·6 | 31·8 ± 1·4 | ||

| Cotyledon | M | 50·1 ± 1·4* | 10·0 ± 0·7* | 9·8 ± 0·5* | 19·8 ± 1·0* | |

| BS | 57·1 ± 0·9 | 16·7 ± 0·6 | 12·6 ± 0·6 | 29·3 ± 1·1 | ||

Means are from 6–10 individual measurements ± standard error.

* Indicates significant differences between M and BS chloroplasts in column for each species and organs separately, at P ≤ 0·05.

**Data are shown only for adaxial BS and M chloroplasts.

**Data from Voznesenskaya et al. (2007a).

† The granal index was calculated as the percentage of the length of all appressed thylakoid membranes to the total length of all thylakoid membranes in a chloroplast.

‡ Thylakoid density in this case is the length of thylakoid membranes (in µm) per 1 µm2 of chloroplast stroma area (analyzed for the total area excluding starch grains).

In leaves (Fig. 4E) and cotyledons (not shown) of C. oxalidea, BS cells are about 25–30 µm in diameter and the cell wall thickness is half that of C. gynandra (Table 3). The BS cell wall thickness in C. oxalidea towards the intercellular air space is only 2-fold greater than that of the M cell wall, and is nearly equal to the combined thickness of the adjacent BS and M cell walls (Fig. 4F, Table 3); plasmodesmata are distributed in the pit fields. Bundle sheath chloroplasts have a thylakoid system consisting of long, small grana (mostly 2–3, rarely up to seven thylakoids in a stack) with few intergranal thylakoids (see Fig. 4G for leaf BS chloroplast). The chloroplasts in M cells also have small grana consisting mostly of paired thylakoids and up to six or seven thylakoids in a stack, but these chloroplasts have longer intergranal thylakoids (Fig. 4H). A more detailed study of the structure, with calculation of the granal indices, shows that the value in BS chloroplasts is higher than in M chloroplasts due to increased density of non-appressed thylakoids in the M chloroplasts (1·7-fold higher in leaves and 1·8-fold higher in cotyledons, Table 4). Bundle sheath cells contain numerous, large mitochondria (Table 3) with tubular cristae (Fig. 4G, insertion).

Bundle sheath cells in leaves of C. angustifolia are about 25–35 µm in diameter (Fig. 4I) and their cell walls facing the intercellular air space are three times thicker than the M cell walls (Table 3). The BS cell wall thickness towards the intercellular air space is also greater than the combined thickness of the BS and M cell walls which are adjacent to each other between pit fields with plasmodesmata (Fig. 4J, Table 3). In leaves and cotyledons of this species, chloroplasts in BS (Fig. 4K for leaf) and M (Fig. 4L for leaf) cells look very similar in appearance; they have well-developed grana generally consisting of 3–5 thylakoids, but as many as 11, which is in contrast to the reduced size of grana in C. oxalidea. In leaves, the granal index of BS chloroplasts is only 1·2-fold higher than that of M chloroplasts; the appressed thylakoid density is similar, but the density of non-appressed thylakoids is 1·3-fold higher in M than in BS chloroplasts (Table 4). Cotyledons of this species have no significant difference between granality of adaxial BS and M chloroplasts (Table 4), while M chloroplasts on the abaxial side have a granal index a little higher than that of the adaxial M chloroplasts (57·2 ± 0·02 vs. 50·6 ± 1·9, with a BS to M ratio of 1·6; data not shown). In leaves and cotyledons of this species, all BS cells (irrespective of their position in the blade) contain numerous, large mitochondria (Table 3) with tubular cristae, sometimes having a lamellate appearance (Fig. 4K).

Cleome paradoxa leaves have large BS cells (approx. 40 µm in diameter) which contain most organelles in a centripetal position, close to the VBs, with some chloroplasts also distributed along the cell wall adjacent to M cells and often associated with air spaces (Fig. 4M). In this species, the BS cell wall facing the intercellular air space is about twice as thick as the M cell wall but is less than the combined thickness of the BS and M cell walls adjacent to each other between plasmodesmata (Fig. 4N, Table 3). In cotyledons and leaves of C. paradoxa, BS and M chloroplasts have well-developed grana (Fig. 4O, P; and for leaves, see also Voznesenskaya et al., 2007a). In leaves the granal indices are similar between the M and BS chloroplasts, but the thylakoid density in BS chloroplasts is about 1·5-fold higher than in M chloroplasts (Table 4). In cotyledons of C. paradoxa, the granal index and thylakoid densities are the same between M and BS chloroplasts. The size of BS mitochondria is twice that of the mitochondria in M cells (Table 3) and they contain well-developed cristae (Fig. 4O).

For comparison, structural features in cotyledons and leaves of the C3 species C. africana were studied by electron microscopy (Supplementary Data Fig. S1, available online). The BS cells are about 25–30 µm in diameter, with few organelles compared with the C4 species, most of which are in a centrifugal position along the proximal cell wall (Fig. S1E). In this species, the thickness of BS cell walls towards the air spaces is equal to the thickness of the M cell wall, and the combined thickness of adjacent BS and M cell walls is about twice that of individual M or BS cell walls (Fig. S1F, Table 3). Bundle sheath and M chloroplasts have a well-developed thylakoid system, with numerous grana consisting mostly of 3–8 thylakoids (Fig. S1G, H). In cotyledons, the granal index is about 1·1-fold higher in BS than in M chloroplasts, while, in leaves, both types of chloroplasts have similar values of granal indices. The appressed thylakoid density and the total thylakoid density are significantly higher in BS compared with M chloroplasts for both leaves and cotyledons (Table 4). The mean diameter of mitochondria in BS cells in this species is slightly lower than in M cells (Table 3).

Western blot analysis

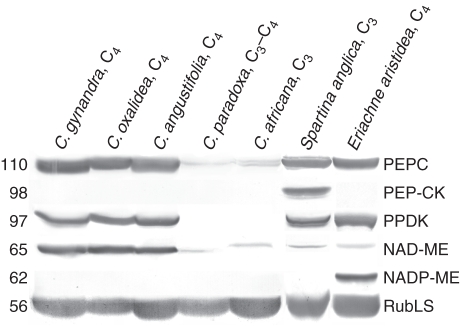

Immunoblots are shown for key photosynthetic enzymes in C4 photosynthesis, PEPC, PEP-CK, PPDK, NAD-ME and NADP-ME, and for Rubisco of the C3 cycle, from soluble protein extracts from leaves of all three C4 Cleome species, the C3–C4 intermediate C. paradoxa and the C3 species C. africana (Fig. 5). Cleome gynandra, C. oxalidea and C. angustifolia have significant immunoreactivity for three C4 pathway enzymes, PEPC, PPDK and NAD-ME, while in C. paradoxa and C. africana there was very low intensity immunolabelling for PEPC and NAD-ME, and no labelling for PPDK. There were no immunoreactive bands for NADP-ME and PEP-CK in any of the Cleome species studied, while strong bands were detected for NADP-ME in protein extracts from the NADP-ME biochemical-type plant E. aristidea and for PEP-CK in extracts from the known PEP-CK-type species S. anglica (Fig. 5). Significant levels of Rubisco were detected in all species using antibody against the large subunit.

Fig. 5.

Western blots for C4 enzymes and Rubisco from soluble protein extracted from leaves of C. gynandra, C. oxalidea, C. angustifolia, C. paradoxa and C. africana, as well as from leaves of Spartina anglica and Eriachne aristidea. Blots were probed with antibodies raised against PEPC, PEP-CK, PPDK, NAD-ME, NADP-ME and the Rubisco large subunit, respectively. Numbers on the left indicate the molecular mass in kiloDaltons.

In situ immunolabelling

Cotyledons and leaves of C. gynandra show clear selective labelling for Rubisco (Fig. 6A, C) in BS chloroplasts, while selective labelling for PEPC (Fig. 6B, D) is confined to M cells. Occasional bright labelling of the content of epidermal cells with PEPC antibodies represents background due to antibodies sticking to tannins (see Voznesenskaya et al., 2001).

Fig. 6.

Reflected/transmitted confocal imaging of in situ immunolocalization of photosynthetic enzymes in (A, B, E, F, I, J) cotyledons and (C, D, G, H, K, L) leaves of (A–D) C. gynandra, (E–H) C. oxalidea and (I–L) C. angustifolia. Immunolabel appears as bright dots. (A, C, E, G, I, K) Rubisco. (B, D, F, H, J, L) PEPC. BS, bundle sheath cells; M, mesophyll cells. Scale bars = 50 µm.

In cotyledons and leaves of C. oxalidea, immunolabelling for Rubisco (Fig. 6E, G) is largely confined to the chloroplasts of BS cells, while PEPC (Fig. 6F, H) is localized in M cells which are in direct contact with BS cells; spongy parenchyma cells on the abaxial side of the cotyledon and leaf blades show little or no labelling for PEPC or Rubisco.

Cotyledons and leaves of C. angustifolia show clear labelling for Rubisco (Fig. 6I, K) in chloroplasts of BS cells irrespective of their positioning on the adaxial or abaxial side, and labelling for PEPC is clearly confined to the M cells which are in direct contact with BS cells (Fig. 6J, L). The double layer of spongy parenchyma cells on the abaxial side of the leaf has little or no labelling for Rubisco or PEPC.

DISCUSSION

C4 Cleome

Prior to this study, C. gynandra was the only established C4 species in family Cleomaceae. Cleome angustifolia and C. oxalidea were previously suggested to be C4 based on the δ13C of herbarium specimens from natural habitats (Voznesenskaya et al., 2007a). Analyses of anatomy, ultrastructure of chloroplasts and mitochondria, levels of C4 enzymes and immunolocalization of carboxylases indicate that C. angustifolia and C. oxalidea, along with C. gynandra, are NAD-ME-type C4 species (as shown by western blots for C4 decarboxylases; there was no detection of PEP-CK or NADP-ME).

Types of Kranz anatomy in Cleome

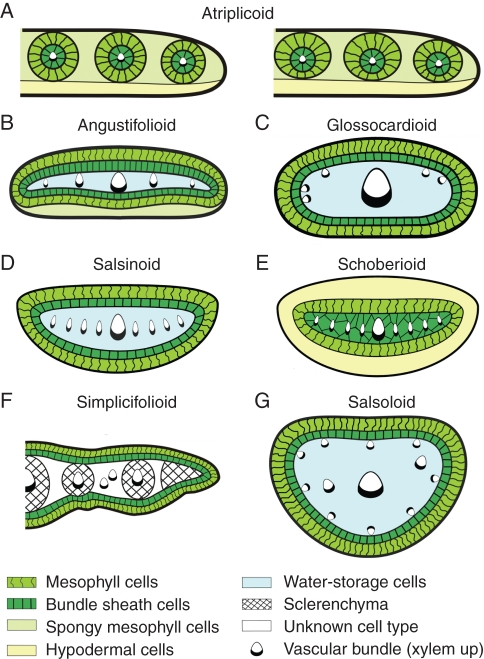

Figure 7 and Table S1 (Supplementary Data, available online) summarize the features of Kranz anatomy observed in Cleome and compare them with other structural forms.

Fig. 7.

Illustrations showing differences between the types of Kranz anatomy found in leaves and cotyledons of Cleome species (A–C), with special attention to the types of anatomy in C. angustifolia (B, C) compared with other forms of Kranz with continuous dual layers of chlorenchyma on the periphery (D–G; see Table S1 for further description of the features). (A) Atriplicoid type of anatomy, with variation in even (left panel, found in leaves and cotyledons of C. oxalidea) and uneven (right panel, found in leaves and cotyledons of C. gynandra) distribution of palisade mesophyll around bundle sheath cells. (B) Angustifoliod type found in the cotyledons of C. angustifolia with all vascular bundles in the lateral plane. (C) Glossocardioid type of anatomy which occurs in C. angustifolia leaves and in genera Glossocardia and Isostigma, family Asteraceae. (D, E) Salsinoid and schoberioid types of Kranz anatomy in genus Suaeda, family Chenopodiaceae. (F) Simplicifolioid type of Kranz anatomy with most vascular bundles distributed in the lateral plane, found in genus Isostigma. (G) Salsoloid type of anatomy described for many genera in subfamily Salsoloideae, family Chenopodiaceae. (Das and Raghavendra, 1976; Kadereit et al., 2003; Peter and Katinas, 2003; Edwards and Voznesenskaya, 2011).

Cotyledons and leaves of C. gynandra and C. oxalidea have atriplicoid-type anatomy with multiple simple Kranz units, a widely distributed form among C4 eudicots (Sage, 2004; Muhaidat et al., 2007; Edwards and Voznesenskaya, 2011), with centripetal positioning of organelles in BS cells. In the simplest form as seen in C. oxalidea there is a more or less radial uniform distribution of palisade M around the BS cells; whereas, in C. gynandra, M cells have a palisade shape on the adaxial side; but on the abaxial side M cells are smaller and irregularly shaped, resembling spongy parenchyma. There is diversity in atriplicoid-type anatomy among the various families where it has been observed, depending on the presence/absence of a hypodermal layer or the presence of additional cells or layers of spongy parenchyma abaxial to the Kranz chlorenchyma (Kadereit et al., 2003; Muhaidat et al., 2007). Kadereit et al. (2003) suggested further sub-divisions for species of the families Chenopodiaceae and Amaranthaceae with atriplicoid-type anatomy. The Gomphrena form of atriplicoid anatomy they described resembles the form observed in C. gynandra and C. oxalidea, since they have an additional layer of spongy parenchyma on the abaxial side of the leaf external to the Kranz chlorenchyma. The similar occurrence of an additional layer of spongy parenchyma on the abaxial side of the leaf has been shown for C4 species from different eudicots families, e.g. Zaleya pentandra (Aizoaceae), Kallstroemia grandiflora (Zygophyllaceae), Heliotropium polyphyllum (Boraginaceae) and Atriplex polycarpa (Chenopodiaceae) (Muhaidat et al., 2007). This is a further example of convergent evolution in C4 with formation of a similar structure in unrelated systematic lineages.

Cotyledons of C. angustifolia have a type of Kranz anatomy not described previously in Cleomaceae or other families. The anatomy consists of one compound Kranz unit enclosing all the VBs, which are distributed in a lateral, longitudinal plane separated by colourless water storage parenchyma cells. The clear dorsiventral pattern, with two layers of spongy parenchyma tissue underneath the compound Kranz unit on the abaxial side of the blade, is a major feature, unique among C4 eudicots, and it distinguishes this form of anatomy (named angustifolioid) from all other Kranz types (Fig. 7B, Table S1). The distribution of VBs in a lateral plane in this type of anatomy resembles the vasculature found in three other forms of Kranz anatomy having a single compound Kranz unit: salsinoid and schoberioid, in the genus Suaeda, family Chenopodiaceae (Kadereit et al., 2003; Schütze et al., 2003), and the simplicifolioid type, first described for Isostigma simplicifolium, family Asteraceae (as well as for I. speciosum; N. K. Koteyeva et al., unpubl. res.; and, see Edwards and Voznesenskaya, 2011). Salsinoid-type anatomy has internal water storage tissue surrounded by the Kranz chlorenchyma, but, unlike the angustifolioid type, it has no parenchyma cells between the Kranz complex and the epidermis, and VBs have no direct contact with BS cells (Fig. 7D). In the schoberioid type, internal water storage tissue is lacking; rather, there are enlarged hypodermal cells which completely surround the Kranz chlorenchyma tissue (Fig. 7E). The simplicifolioid type (Fig. 7F, Table S1) has a continuous dual layer of cells forming Kranz anatomy around the leaf periphery, with all VBs distributed in a lateral longitudinal plane. It is similar to the angustifolioid type in terms of the positioning of all veins between chlorenchyma layers; however, it has no additional parenchyma layers between chlorenchyma and epidermis cells and there is no direct contact between VBs and chlorenchyma in I. simplicifolium.

A different type of Kranz anatomy with a continuous ring of two-layered chlorenchyma on the leaf periphery was found in the very narrow leaflets of C. angustifolia. The vascular system consists of a few, scattered (not very frequent and irregularly located) veins, with the main vein in the centre and a cluster of small veins in the marginal positions. There are no secondary bundles which go through water storage tissue parallel to the main vein in leaves of this species on the same level. Rather, from the main vein, the lateral VBs extend almost directly to the adaxial side of the leaf where they come into contact with the BS cells by their xylem side. A similar form of Kranz anatomy was observed earlier in family Asteraceae in Glossocardia bosvallia by Das and Raghavendra (1976) and, more recently, a similar type of anatomy was found in some species of Isostigma (Peter and Katinas, 2003; N. K. Koteyeva et al., unpubl. res.); this form of Kranz was named glossocardioid type (Edwards and Voznesenskaya, 2011; Fig. 7C ). It has some similarity to the salsoloid type of Kranz anatomy described in terete leaves of a number of species in the family Chenopodiaceae (Fig. 7G, Table S1). They have in common the peripheral position of chlorenchyma tissue external to water storage parenchyma, positioning of the main VB in the centre and contact of the peripheral VBs with BS on their xylem side (Carolin et al., 1975; Edwards and Voznesenskaya, 2011). However, the distinguishing difference is the arrangement of secondary veins in water storage tissue and positioning of peripheral VBs. In salsoloid anatomy, descending secondary bundles run nearly parallel to the main vein through water storage tissue (Fahn and Broido, 1963), with more or less uniform positioning of small VBs around the leaf periphery; whereas, in the glossocardioid type which occurs in C. angustifolia leaves, all of the peripheral VBs are distributed adjacent to the Kranz chlorenchyma tissue on the adaxial and lateral sides of the leaf.

In summary, families having a form of Kranz anatomy with a continuous concentric dual chlorenchyma layer around the periphery of assimilating organs include Asteraceae, Chenopodiaceae, Cleomaceae (current study) and Polygonaceae. A number of distinct types have been recognized, including angustifolioid (current study), glossocardioid, salsoloid, salsinoid, schoberioid, tecticornoid and simplicifolioid (Brown, 1975; Carolin et al., 1975; Shomer-Ilan et al., 1975; Das and Raghavendra, 1976; Winter et al., 1977; Shomer-Ilan et al., 1979; Shomer-Ilan et al., 1981; Carolin et al., 1982; Voznesenskaya and Gamaley, 1986; Fisher et al., 1997; Sage et al., 1999; Pyankov et al., 2000b; Jacobs, 2001; Kadereit et al., 2003; Peter and Katinas, 2003; Schütze et al., 2003; Muhaidat et al., 2007; Voznesenskaya et al., 2007b, 2008; Edwards and Voznesenskaya, 2011). Differences occur in the distribution and positioning of VBs, the volume and positioning of water storage tissue and the occurrence of spongy parenchyma and hypodermal cells (and, when present their size, e.g. large water storage-like hypodermal cells in the schoberioid type). This indicates that certain forms of Kranz anatomy evolved independently a number of times in distant branches of these eudicot families.

Kranz anatomy in cotyledons vs. leaves of Cleome

In the present study, both cotyledons and leaves of three C4 species of Cleome show clear development of Kranz anatomy with NAD-ME-type C4 photosynthesis, although there are structural differences. Among the three C4 Cleome species, two (C. gynandra and C. oxalidea) have atriplicoid-type anatomy in cotyledons and leaves with a similar degree of structural development of Kranz tissues. In contrast, C. angustifolia has a single compound Kranz unit with glossocardioid-type anatomy in leaves and angustifolioid-type anatomy in cotyledons, with both having water storage tissue in the central part of the blade (which occupies a larger volume in leaves than in cotyledons). Both leaves and cotyledons of C. paradoxa have an anatomy characteristic of C3–C4 intermediate species (Edwards and Ku, 1987), with an increased number of organelles in the centripetal position in enlarged BS cells. The C3 species C. africana has a similar dorsiventral C3-type of anatomy in both cotyledons and leaves.

Previous studies on C4 eudicots have shown there is also diversity in the form of photosynthesis in cotyledons (whether it is C3 or C4, and, if C4, whether the form of Kranz is the same as in leaves). In general, in most C4 eudicots, the cotyledons also possess C4 photosynthesis (Butnik 1979, 1984; Butnik et al., 1991; Pyankov et al., 2000a, b; Voznesenskaya et al., 2004; Akhani and Ghasemkhani, 2007). However, some C4 species have leaves and cotyledons with different types of Kranz anatomy (as observed in C. angustifolia in the current study), while there are others having leaves which possess Kranz anatomy, but cotyledons with C3 anatomy and photosynthesis (as found in the family Chenopodiaceae; Butnik, 1979, 1984; Butnik et al., 1991; Voznesenskaya et al., 1999; Pyankov et al., 2000a). No cases have been found where cotyledons have C4 anatomy and leaves have C3 anatomy.

Features of mesophyll and bundle sheath cells of C4 Cleome

Cell walls

In the three C4 Cleome species, the BS cell walls facing the intercellular air space are thicker than the M cell walls (2–5 times depending on the species) and are equivalent to, or greater than (P < 0·05), the combined thickness of the BS and M cell walls when in contact with each other between pit fields where plasmodesmata are distributed. In contrast to the C4 species, in C3 C. africana the BS cell wall thickness at the intercellular air space is not significantly different (P < 0·05) from the M cell wall thickness, while in C3–C4 intermediate C. paradoxa they are twice as thick as the M cell walls (P < 0·05), but they are thinner than in the C4 species. The combined thickness of M and adjacent BS cell walls between pit fields (or between plasmodesmata in C3 species) is highest in C. gynandra, followed by C. oxalidea, and lowest in the remaining species. The greater thickness of BS cell walls in the C4 Cleome species may contribute to resistance to diffusion of CO2 and reduction of its leakage from BS cells during C4 photosynthesis. From the C4 species previously analysed, this BS cell wall thickening is usually much more pronounced in species with the NADP-ME biochemical type; however, the degree of thickening in NAD-ME species is species or taxon specific, especially in eudicots, from rather limited thickening in Atriplex and Suaeda species, both from the family Chenopodiaceae (Voznesenskaya et al., 2007b), to rather thick cell walls in Tecticornia indica ssp. indica, family Chenopodiaceae (Voznesenskaya et al., 2008). Some grasses have specialized suberin lamellae in BS cell walls (not found in any of the eudicots, including C4 Cleome), which may provide additional diffusive resistance to leakage of CO2 from the BS (Dengler and Nelson 1999; von Caemmerer and Furbank, 2003; Edwards and Voznesenskaya, 2011). Bundle sheath cell wall thickness between the BS/M interphase has been reported to vary between 0·13 and 0·66 µm in some representative C4 species, and various resistances to CO2 leakage from BS cells are proposed for the different C4 subtypes (von Caemmerer and Furbank, 2003). In the C4 Cleome species, this would include positioning of mitochondria (the site of C4 decarboxylation) in the centripetal position along with BS chloroplasts, the long liquid phase diffusion path from the centripetal position to the distal side of the BS cell and the increased thickness of the BS cell wall, especially in contact with the intercellular air space.

Structure of chloroplasts

Comparisons of the structure of M and BS chloroplasts in the C4 vs. the intermediate and a C3 species were made on plants grown under similar conditions in the greenhouse. In all three C4 Cleome species, the two chloroplast types have structural features which are typical of plants having NAD-ME-type biochemistry (see Introduction) with a higher degree of grana development in BS chloroplasts compared with M chloroplasts (except in cotyledons of C. angustifolia which has Kranz anatomy without structural differentiation of the chloroplasts). In contrast to the C4 species, there was no significant difference in the granal indices between M and BS chloroplasts in leaves and cotyledons of C. paradoxa. Also, in the C3 species C. africana the granal index is very similar between M and BS chloroplasts, with the cotyledons having a slightly higher BS/M granal index ratio. Thus, the chloroplasts in M and BS cells of the intermediate and C3 species do not show structural differentiation associated with C4 photosynthesis in NAD-ME-type C4 species.

The occurrence of a higher granal index in BS than in M chloroplasts in the three C4 Cleome species was achieved in different ways. In C. oxalidea and C. angustifolia, there is an increased density of the non-appressed thylakoids in M compared with BS chloroplasts, with nearly equal densities of appressed thylakoids in both types of chloroplasts. However, in C. gynandra, a higher granal index for BS chloroplasts was achieved by an increase in the appressed thylakoid density in BS chloroplasts, as well as by an increase in the non-appressed thylakoid density of M chloroplasts (see Table 4). Along with these differences, the thylakoid systems of BS and M chloroplasts in C. gynandra and C. angustifolia are similar in appearance with well-developed mid-sized grana, whereas in C. oxalidea they have mostly paired thylakoids. The results indicate that higher granal index values occurred in BS than M chloroplasts irrespective of differences in the structure of grana. Thus, the size of individual grana is not correlated with the degree of development of grana vs. non-appressed thylakoids, and quantitative analyses are required to determine the granal index.

The high ratios of BS/M granal indices (1·5–2) observed in leaves and cotyledons of C. oxalidea and C. gynandra have been observed in other NAD-ME C4 eudicots in the family Chenopodiaceae. This includes a ratio of 1·5 in the single-cell C4 species Bienertia cycloptera, with the chloroplasts in the central cytoplasmic compartment/peripheral cytoplasm functionally analogous to BS/M (Voznesenskaya et al., 2002), a ratio of 1·6 in the Kranz C4 species Halocharis gossypina (Voznesenskaya et al., 1999), and, in Salsola laricina, a ratio of 1·4 for cotyledons and an especially high ratio of 2·5 for leaves (Voznesenskaya et al., 1999). The magnitude of the increase in granal density in BS compared with M chloroplasts varies between species (which might be affected in part by differences in growth conditions) and within a species between photosynthetic organs. Since the cotyledons of C. angustifolia have similar granal index values in M and BS chloroplasts, it suggests differences in cooperative function of the two cell types in supporting an NAD-ME-type C4 system. The results suggest that the trait of a higher granal index of BS chloroplasts in these NAD-ME species of Cleome had distinct origins with convergent evolution.

Structure of mitochondria

All three C4 species have large mitochondria with numerous tubular cristae in BS cells (mean diameter of 0·92 µm in BS vs. 0·45 µm in M cells), which is typical of species with NAD-ME-type biochemistry where they participate in decarboxylation of malate by mitochondrial NAD-ME (Edwards and Walker, 1983). The BS mitochondria in the C3–C4 intermediate species C. paradoxa are smaller (0·66 µm) and the cristae are not as extensively developed as the BS mitochondria of the C4 Cleome species. The mitochondria in BS cells of C. paradoxa are twice as large as in M cells and are mostly concentrated in the centripetal position. The increased number of enlarged BS mitochondria with specific positioning is characteristic of species with C3–C4 intermediate type of photosynthesis. In intermediates, decarboxylation via glycine decarboxylase is confined to mitochondria in BS cells which allows photorespiration to be reduced by refixation of photorespired CO2 (Edwards and Ku, 1987; Rawsthorne, 1992; Voznesenskaya et al., 2001, 2007a). The mitochondria in the BS cells of the C3 species C. africana, which lack the selective functions of the C4 and intermediate species, are smaller (approx. 0·3 µm) and distributed around the BS cell (see also data on mitochondria size for other Cleome species in Voznesenskaya et al., 2007a).

Structural forms and biogeography of C4 Cleome

The three C4 species of Cleome in this study, which have differences in leaf morphology and Kranz type anatomy, belong to separate clades based on a recent phylogenetic study (Feodorova et al., 2010). Cleome gynandra occurs in clade Gynandropsis; C. oxalidea is sister to C3 species in a clade containing Australian species; C. angustifolia forms a clade with the C3–C4 intermediate C. paradoxa, and C. luderitziana (unknown photosynthetic type with C3-like value of δ13C); while, the C3 species C. africana is in a separate clade from that of the C4 species. Cleome angustifolia, which has narrow leaflet leaves, is an African species which grows in low rainfall and semi-desert areas with a tendency to become a weed on stony ground. The closely related C3–C4 intermediate C. paradoxa also has leaves with narrow leaflets, and grows in areas of limited rainfall in Eastern Africa and Saudi Arabia (Vesey-Fitzgerald, 1957). Cleome gynandra, which has leaves with rather wide leaflets, is a semi-cultivated pantropical species. Cleome oxalidea is an Australian endemic which grows in arid regions with tropical summer rain (http://florabase.calm.wa.gov.au/). The occurrence of Kranz anatomy as a single compound unit in semi-terete leaves of C. angustifolia, and as forms of atriplicoid-type anatomy in C. gynandra and C. oxalidea, may be related to their growth in semi-arid/arid vs. more mesic habitats. As a general rule, changes in leaf morphology during plant adaptation to increasing aridity and solar radiation, and decreasing water availability, involve a decrease of leaf area and, in some xerophytic species, an increase in succulence (Fahn and Cutler, 1992; Eggli, 2002). This was previously observed among C4 species in a number of families including Asteraceae (Peter and Katinas, 2003), Chenopodiaceae (Kadereit et al., 2003) and Portulacaceace (Eggli, 2002), and in Cleomaceae in the present study.

On the basis of the study of leaf venation, two different means of adaptation of Cleome species to drought and high temperature stress can be suggested. One well-known means is by increasing vein density in the laminate leaves, which is also characteristic of the higher order of branches which is known as ‘Zalenski's law’ (Zalenski, 1902). Differences in vein density in leaves of several Cleome species suggest clear steps in this direction. In some mesophytic C3 species, there are 8–10 M cells between neighbouring BS cells, compared with 2–4 M cells in the C3 species C. africana and C. ornithopodioides; and, in the most striking case, the African C3–C4 intermediate C. paradoxa has the closest VBs, having on average <2 M cells between BS cells (Marshall et al., 2007; Voznesenskaya et al., 2007a). Both of the C4 species C. oxalidea and C. gynandra have very close positioning of veins in the leaves (Fig. 3A, B; for C. gynandra, see also Marshall et al., 2007; Voznesenskaya et al., 2007a). Another means of adaptation to drought and high temperature stress is illustrated by C. angustifolia, which has narrow leaflet leaves, with rather well-developed water storage tissue internal to the concentric layers of Kranz chlorenchyma, indicating development of some features characteristic of succulent plants. These leaves show a reduction in reticulate venation and terminal minor veins, and development of nearly parallel venation with rare anastomoses (see Fig. 3C, D); evolution of a similar leaf structure has also been observed in the genus Isostigma in the family Asteraceae under increased water stress (Peter and Katinas, 2003).

In summary, the anatomical and ultrastructural differences, and biogeographic information, show diversity in the occurrence of C4 photosynthesis in Cleomaceae. The results suggest alternative forms of Kranz anatomy may have evolved in the family from C3 ancestors that had leaf structures adapted to different environments. Future studies on anatomy and photosynthesis of closely related Cleome species in certain lineages may provide insight into the ancestors, the steps leading to evolution of C4 photosynthesis and the developmental history of Kranz anatomy in the family. This could be facilitated by analysis of genomic information (Bräutigam et al., 2010).

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at www.aob.oxfordjournals.org and consist of the following files. Figure S1. Structural features of Cleome africana, a representative C3 Cleome species that was used in the study. Table S1. Comparison of structural forms of Kranz in Cleome to some other forms in C4 dicots.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank C. Cody for plant growth management, and the Franceschi Microscopy and Imaging Center of Washington State University for use of its facilities and staff assistance. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grants IBN-0236959 and IBN 0641232, NSF Isotope Facility Grant DBI-0116203 and, in part, by Civilian Research and Development Foundation grants RB1-2502-ST-03 and RUB1-2829-ST-06, and Russian Foundation of Basic Research grant 08-04-00936.

LITERATURE CITED

- Akhani H, Ghasemkhani M. Diversity of photosynthetic organs in Chenopodiaceae from Golestan National Park (NE Iran) based on carbon isotope composition and anatomy of leaves and cotyledons. Nova Hedwigia Suppl. 2007;131:265–277. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JM. Insights into the consequences of grana stacking of thylakoid membranes in vascular plants: a personal perspective. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology. 1999;26:625–639. [Google Scholar]

- Bender MM, Rouhani I, Vines HM, Black CC., Jr 13C/12C ratio changes in Crassulacean acid metabolism plants. Plant Physiology. 1973;52:427–430. doi: 10.1104/pp.52.5.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besnard G, Muthama AM, Russier F, Roalson EH, Salamin N, Christin P-A. Phylogenomics of C4 photosynthesis in sedges (Cyperaceae): multiple appearances and genetic convergence. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2009;26:1909–1919. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bräutigam A, Kajala K, Wullenweber J, et al. An mRNA blueprint for C4 photosynthesis derived from comparative transcriptomics of closely related C3 and C4 species. Plant Physiology. 2010 doi: 10.1104/pp.110.159442. (in press). doi:10.1104/pp.110.159442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown NJ, Parsley K, Hibberd JH. The future of C4 research – maize, Flaveria or Cleome? Trends in Plant Science. 2005;10:215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown WV. Variations in anatomy, associations, and origin of Kranz tissue. American Journal of Botany. 1975;62:395–402. [Google Scholar]

- Butnik AA. Types of seedling development of Chenopodiaceae Vent. Botanicheskii Zhurnal. 1979;64:834–842. (in Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Butnik AA. The adaptation of anatomical structure of the family Chenopodiaceae Vent. species to arid conditions. Summary of biological science doctor degree thesis. Tashkent: Academy of Sciences of Uzbek SSR; 1984. (in Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Butnik AA, Nigmanova RN, Paisieva SA, Saidov DK. Ecological anatomy of desert plants of middle Asia. V.1. Trees, shrubs, semi-shrubs. Tashkent: FAN; 1991. (in Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Carolin RC, Jacobs SWL, Vesk M. Leaf structure in Chenopodiaceae. Botanische Jahrbücher für Systematik, Pflanzengeschichte und Pflanzengeographie. 1975;95:226–255. [Google Scholar]

- Carolin RC, Jacobs SWL, Vesk M. Kranz cells and mesophyll in the Chenopodiales. Australian Journal of Botany. 1978;26:683–698. [Google Scholar]

- Carolin RC, Jacobs SWL, Vesk M. The chlorenchyma of some members of the Salicornieae (Chenopodiaceae) Australian Journal of Botany. 1982;30:387–392. [Google Scholar]

- Christin P-A, Salamin N, Kellogg EA, Vicentini A, Besnard G. Integrating phylogeny into studies of C4 variation in the grasses. Plant Physiology. 2009;149:82–87. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.128553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das VSR, Raghavendra AS. C4 photosynthesis and a unique type of Kranz anatomy in Glassocordia boswallaea (Asteraceae) Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences. 1976;84B, 1:12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Dengler NG, Nelson T. Leaf structure and development in C4 plants. In: Sage RF, Monson RK, editors. C4 plant biology. Physiological ecology series. San Diego: Academic Press; 1999. pp. 133–172. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards GE, Ku MSB. The biochemistry of C3–C4 intermediates. In: Hatch MD, Boardman NK, editors. The biochemistry of plants. Vol. 10, photosynthesis. New York: Academic Press; 1987. pp. 275–325. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards GE, Walker DA. C3, C4: mechanisms, and cellular and environmental regulation, of photosynthesis. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards GE, Voznesenskaya EV. C4 photosynthesis: Kranz forms and single-cell C4 in terrestrial plants. In: Raghavendra AS, Sage RF, editors. C4 photosynthesis and related CO2 concentrating mechanisms. Advances in photosynthesis and respiration. Vol. 32. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2011. pp. 29–61. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards GE, Franceschi VR, Voznesenskaya EV. Single cell C4 photosynthesis versus the dual-cell (Kranz) paradigm. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2004;55:173–196. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards GE, Voznesenskaya EV, Smith M, et al. Breaking the Kranz paradigm in terrestrial C4 plants: does it hold promise for C4 rice? In. In: Sheehy JE, Mitchell PL, Hardy B, editors. Charting new pathways to C4 rice. Los Banos, Philippines: International Rice Research Institute, World Scientific; 2007. pp. 249–273. [Google Scholar]

- Eggli U. Illustrated handbook of succulent plants: dicotyledons. Berlin: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Elffers J, Graham RA, Dewolf GP. Capparidaceae. In: Hubbard CE, Milne-Redhead E, editors. Flora of tropical east Africa. London: Whitefriars Press; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Fahn A, Broido S. The primary vascularization of the stems and leaves of the genera Salsola and Suaeda (Chenopodiaceae) Phytomorphology. 1963;13:156–165. [Google Scholar]

- Fahn A, Cutler DF. Xerophytes. Encyclopedia of plant anatomy. Berlin: Gebruder Borntraeger; 1992. p. 176. Vol. XIII, Part 3. [Google Scholar]

- Feodorova TA, Voznesenskaya EV, Edwards GE, Roalson EH. Biogeographic patterns of diversification and the origins of C4 Cleome (Cleomaceae) Systematic Botany. 2010 (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Fisher DD, Schenk HJ, Thorsch JA, Ferren WR., Jr Leaf anatomy and subgeneric affiliation of C3 and C4 species of Suaeda (Chenopodiaceae) in North America. American Journal of Botany. 1997;84:1198–1210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamaley YV. The variations of the Kranz-anatomy in Gobi and Karakum plants. Botanicheskii Zhurnal. 1985;70:1302–1314. (in Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Hall JC, Sytsma KJ, Iltis HH. Phylogeny of Capparaceae and Brassicaceae based on chloroplast sequence data. American Journal of Botany. 2002;89:1826–1842. doi: 10.3732/ajb.89.11.1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch MD. C4 photosynthesis: a unique blend of modified biochemistry, anatomy and ultrastructure. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1987;895:81–106. [Google Scholar]

- Hewson HJ, editor. Capparaceae. Vol. 8. Victoria, Australia: CSIRO Publishing; 1982. pp. 223–231. Collingwood. [Google Scholar]

- Hooker JD. Flora of British India. Vol. 1. London: L: Reeve and Co., Ltd; 1875. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs SWL. Review of leaf anatomy and ultrastructure in the Chenopodiaceae (Caryophyllales) Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society. 2001;128:236–253. [Google Scholar]

- Kadereit G, Borsch T, Weising K, Freitag H. Phylogeny of Amaranthaceae and Chenopodiaceae and the evolution of C4 photosynthesis. International Journal of Plant Sciences. 2003;164:959–986. [Google Scholar]

- Kanai R, Edwards G. The biochemistry of C4 photosynthesis. In: Sage RF, Monson RK, editors. C4 plant biology. Physiological ecology series. San Diego: Academic Press; 1999. pp. 49–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kapralov MV, Akhani H, Voznesenskaya E, Edwards G, Franceschi VR, Roalson EH. Phylogenetic relationships in the Salicornioideae /Suaedoideae /Salsoloideae s.l. (Chenopodiaceae) clade and a clarification of the phylogenetic position of Bienertia and Alexandra using multiple DNA sequence datasets. Systematic Botany. 2006;31:571–585. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler HK, Kuhn G, Prenzel U, Buschmann C, Meier D. Adaptation of chloroplast-ultrastructure and of chlorophyll-protein levels to high-light and low-light growth conditions. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung. 1982;37:464–475. [Google Scholar]

- Long JJ, Berry JO. Tissue-specific and light-mediated expression of the C4 photosynthetic NAD-dependent malic enzyme of amaranth mitochondria. Plant Physiology. 1996;112:473–482. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.2.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall DM, Muhaidat R, Brown NJ, et al. Cleome, a genus closely related to Arabidopsis, contains species spanning a developmental progression from C3 to C4 photosynthesis. The Plant Journal. 2007;207:886–896. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurino VG, Drincovich MF, Andreo CS. NADP-malic enzyme isoforms in maize leaves. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology International. 1996;38:239–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhaidat RM, Sage RF, Dengler NG. Diversity of Kranz anatomy and biochemistry in C4 eudicots. American Journal of Botany. 2007;94:362–381. doi: 10.3732/ajb.94.3.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell CA, Brown NJ, Liu Z, et al. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of Cleome gynandra L., a C4 dicotyledon that is closely related to Arabidopsis thaliana. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2010;61:1311–1319. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver D. Flora of tropical Africa. Vol. 1. London: L; 1868. Reeve and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Peter G, Katinas L. A new type of Kranz anatomy in Asteraceae. Australian Journal of Botany. 2003;51:217–226. [Google Scholar]

- Post GE. Flora of Syria, Palestine and Sinai; from the Taurus to Ras Muhammad, and from the Mediterranean Sea to the Syrian desert. Beirut, Syria: Syrian Protestant College; 1896. [Google Scholar]

- Pyankov VI, Voznesenskaya EV, Kuz'min A, Ku MSB, Black CC, Edwards GE. Diversity of CO2 fixation pathways in leaves and cotyledons of Salsola (Chenopodiaceae) plants. Doklady Botanical Sciences. 2000a;370:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Pyankov VI, Voznesenskaya EV, Kuz'min AN, et al. Occurrence of C3 and C4 photosynthesis in cotyledons and leaves of Salsola species (Chenopodiaceae) Photosynthesis Research. 2000b;63:69–84. doi: 10.1023/A:1006377708156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavendra AS, Sage RF. C4 photosynthesis and related CO2 concentrating mechanisms. Advances in photosynthesis and respiration. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rawsthorne S. C3–C4 intermediate photosynthesis: linking physiology to gene expression. The Plant Journal. 1992;2:267–274. [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF. The evolution of C4 photosynthesis. New Phytologist. 2004;161:341–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.00974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, Li M, Monson RK. The taxonomic distribution of C4 photosynthesis. In: Sage RF, Monson RK, editors. C4 plant biology. New York: Academic Press; 1999. pp. 551–584. [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, Sage TL, Pearcy RW, Borsch T. The taxonomic distribution of C4 photosynthesis in Amaranthaceae sensu stricto. American Journal of Botany. 2007;94:1992–2003. doi: 10.3732/ajb.94.12.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Acebo L. A phylogenetic study of the new world Cleome (Brassicaceae, Cleomoideae) Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 2005;92:179–201. [Google Scholar]

- Sankhla N, Ziegler H, Vyas OP, Stichler W, Trimborn P. Eco-physiological studies on Indian arid zone plants. V. A screening of some species for the C4-pathway of photosynthetic CO2-fixation. Oecologia. 1975;21:123–129. doi: 10.1007/BF00345555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schütze P, Freitag H, Weising K. An integrated molecular and morphological study of the subfamily Suaedoideae Ulbr. (Chenopodiaceae) Plant Systematics and Evolution. 2003;239:257–286. [Google Scholar]

- Shomer-Ilan A, Beer S, Waisel Y. Suaeda monoica, a C4 plant without typical bundle sheaths. Plant Physiology. 1975;56:676–679. doi: 10.1104/pp.56.5.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shomer-Ilan A, Neumann-Ganmore R, Waisel Y. Biochemical specialization of photosynthetic cell layers and carbon flow paths in Suaeda monoica. Plant Physiology. 1979;64:963–965. doi: 10.1104/pp.64.6.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]