Abstract

Objective

We investigated the role of recombinant human interleukin-11 (rhIL-11) on in vivo mobilization of CD34+/VEGFR2+ mononuclear cells and collateral vessel remodeling in mouse model of hindlimb ischemia.

Methods and Results

We observed that treatment of Sv129 mice with continuous infusion of 200 μg/kg/day of rhIL-11 led to in vivo mobilization of CD34+/VEGFR2+ cells that peaked at 72 hours. Sv129 mice pre-treated with rhIL-11 for 72 hours prior to femoral artery ligation showed a 3-fold increase in plantar vessel perfusion leading to faster blood flow recovery and a 20-fold increase in circulating CD34+/VEGFR2+ cells after 8 days of rhIL-11 treatment. Histologically, experimental mice had a 3-fold increase in collateral vessel luminal diameter after 21 days of rhIL-11 treatment, and a 4.4-fold influx of perivascular CD34+/VEGFR2+ cells after 8 days of therapy. Functionally, rhIL-11-treated mice showed better hindlimb appearance and use scores, when compared with syngeneic mice treated with PBS under the same experimental conditions.

Conclusions

These novel findings show that rhIL-11 promotes in vivo mobilization of CD34+/VEGFR2+ mononuclear cells, enhances collateral vessel growth and increases recovery of perfusion after femoral artery ligation. Thus, rhIL-11 has a promising role for development as adjunctive treatment of patients with peripheral vascular disease.

Keywords: Peripheral vascular disease, CD34+/VEGFR2+ cells, collateral vessel remodeling, arteriogenesis, hindlimb ischemia

Peripheral vascular disease (PVD) is a major cause of morbidity as well as significant health care cost in the United States1. Currently, it is estimated that over 8 million Americans have PVD2, and its prevalence is expected to increase concurrently with the rise of the aging population. The high rate of morbidity associated with this disease has created a need for identification of novel therapies for adjunctive treatment of patients with PVD.

Collateral vessels are preexisting arteriolar connections, which may not be utilized to provide perfusion under normal conditions, but can be recruited to bypass the site of acute or chronic vessel occlusion. Collateral vessel growth (arteriogenesis) provides a natural adaptive mechanism to lessen tissue injury caused by PVD. However, this process is insufficient in many patients, and therapies to augment it are needed. Several investigators have shown that intramuscular injection of ex vivo-processed autologous mononuclear cells leads to short term symptomatic improvement in patients with PVD3. Others have reported a correlation between patient outcomes and the number of intramuscularly injected CD34+ cells within the patient’s mononuclear cell population 4. Although these studies have demonstrated favorable safety and feasibility of cell-based therapy for treatment of patients with PVD, the need for ex-vivo processing of mononuclear cells prior to delivery is a major impediment to the performance of a large scale study in these patient populations—thus, creating a need for novel method of rapid in vivo mobilization of mononuclear cells for treatment of patients with PVD.

Human blood outgrowth cells (HBOCs) are cultured CD34+/VEGFR2+ mononuclear cells from normal healthy human subjects. These late outgrowth cells have a slow initial rate of growth, and they exhibit tremendous proliferative capacity after several weeks in culture 5, thus serving as useful tools for screening the biology of vasculoprotective mononuclear cells in in vitro assays. We have recently reported that a 12-mer peptide ligand that binds with high affinity to HBOCs has sequence homology to human interleukin-11 (IL-11)6. This finding, coupled with reports of high expression of interleukin-11 receptor alpha (IL-11Rα) in highly vascular tissues 7, suggests a potential role for IL-11 as a putative ligand for in vivo mobilization of mononuclear cells and vascular remodeling.

IL-11 is a member of the interleukin-6 cytokine family. IL-11 is produced by a variety of tissues and has pleiotropic effects on multiple tissues, including promotion of human and murine megakaryocytopoiesis and thrombopoiesis8, 9, protection of endothelial cells from alloinjury by upregulation of survivin 10, 11 and protection against endothelial cell death 12. Fortuitously, rhIL-11 has already been used extensively in human patients 13, 14. Since the clinical efficacy and safety parameters of rhIL-11 have been well characterized in humans, we performed a pre-clinical study to investigate the role of rhIL-11 as a potential pharmacologic agent for in vivo mobilization of CD34+/VEGFR2+ mononuclear cells and collateral vessel remodeling using a mouse model of hindlimb ischemia. We chose CD34+/VEGFR2+ cells since these markers are present in human and mice, have been used to identify mouse progenitor cells that enhance neovascularization during hindlimb ischemia 15, 16, and will allow for correlation of CD34+/VEGFR2+ cells in mice and future human studies.

Methods

Please see online Supplemental material for methods not described here.

Unilateral hindlimb ischemia

Unilateral femoral artery ligation was performed using 10-week old Sv129 mice as previously described 17. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with 1.25% isoflurane/O2 during hindlimb depilation (one day before surgery) and during hindlimb ischemia surgery. The right femoral artery was exposed through a 2 mm incision and ligated with two 7-0 sutures placed proximal to the origin of the lateral caudal femoral artery. The artery was transected and separated. The wound was irrigated with sterile saline and closed, and Cefazolin (50mg/kg, IM), topical Furazolidone and Pentazocine (10mg/kg, IM) were administered. The University of North Carolina Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all our animal procedures.

Laser Doppler perfusion imaging

Laser Doppler perfusion imaging was performed as previously described 17. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with 1.25% isoflurane/O2 and their body temperature was strictly maintained at 37°C ± 0.5 during the entire procedure. Laser Doppler perfusion imaging (Moor Instruments Ltd, Devon, UK) of plantar foot or adductor thigh of both legs was performed before, immediately after and at 2, 4, 6, 8 and 14 days after femoral ligation. Images were analyzed using MoorLDIV5.0 software. Regions of interest (ROI) were drawn with respect to anatomical landmarks and flow rate was calculated. Perfusion in the ligated leg was normalized to the unligated leg. Foot appearance was scored as an indexof ischemia: 0, normal; 1–5, cyanosis or loss of nail(s) (where the score is dependent on the number of nails affected);6–10, partial or complete atrophy of digit(s) (where thescore reflects number of digits affected); 11, partial atrophy of forefoot. Hindlimb use was scored as an index of muscle function: 0, normal; 1, no toe flexion; 2, no plantar flexion; 3, dragging foot.

Statistical Analysis

All data are reported as mean ± SE. Differences were subjected to unpaired t-tests (2-tailed). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

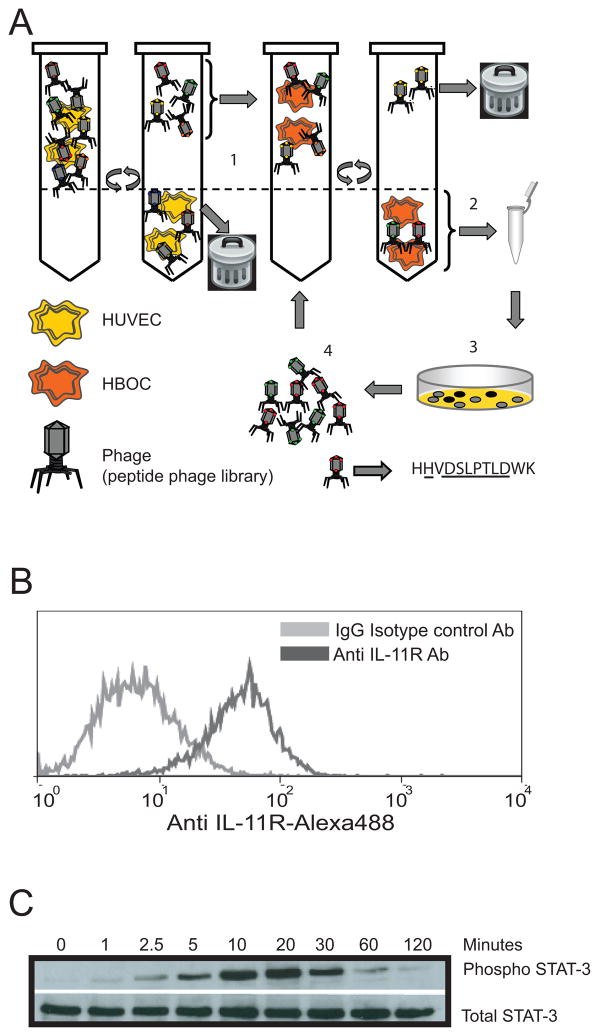

HBOCs express IL-11Rα and administration of rhIL-11 activates downstream STAT-3

We recently identified peptide ligands that bind specifically to HBOCs by screening phage display libraries in order to identify novel surface markers of vasculoprotective mononuclear cells 6 (see cartoon in Figure 1A). One such 12-mer-peptide ligand has sequence homology with human IL-11. This observation, coupled with reports of high expression of IL-11Rα in highly vascular tissues 7, prompted us to investigate the potential significance of the IL-11/HBOC interaction on vascular remodeling. As a first step, we confirmed the phenotype of HBOCs by multi-parametric investigation consisting of identification of their characteristic cobblestone morphology 5, acetylated LDL uptake18 as well as their expression of cell surface markers such as VEGFR2, CD34 and CD31. These characteristics, along with the lack of expression of CD45 (data not shown), 19 suggests that these HBOCs have properties of dedifferentiated mononuclear cells 20. To determine if HBOCs express IL-11Rα, we incubated HBOCs with anti-IL-11Rα antibody and found that HBOCs robustly express IL-11Rα on their surface (Figure 1B). In order to determine if signaling via the IL-11Rα/rhIL-11 (receptor/ligand) axis was intact, we stimulated HBOCs with rhIL-11 and found that rhIL-11-treated cells displayed a time-dependent phosphorylation of STAT-3 (Figure 1C)—a downstream effector molecule that support cell survival by upregulation of anti-apoptotic proteins like survivin 10 and upregulation of pro-angiogenic factors like VEGF 21. These data not only demonstrate that HBOCs express a functional IL-11Rα but also suggest a link between IL-11/HBOC interaction and IL-11Rα signaling.

Figure 1. HBOCs abundantly express interleukin-11 receptor-alpha.

A. Schematic representation of the screening procedure used to identify peptide ligands that selectively bind to HBOCs. A 12-mer random peptide phage display library was screened using a two-step selection protocol. First, the library was depleted of ligands binding to common receptors by incubation with a non-target cell line (HUVEC). Second, the unbound phage pool was biopanned on HBOCs. Phage that bound to HBOC were amplified in Escherichia coli to the original input titer of the library and used for subsequent rounds of biopanning (steps 1 through 4). After three rounds of biopanning, HBOC-bound phage were plaque-purified for sequence analysis6. B. HBOCs were incubated with an anti human IL-11 receptor antibody-Alexa488 or mouse IgG isotype control antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry. HBOCs abundantly express interleukin-11 receptor alpha. C HBOCs were treated with 25ng/ml of rhIL-11 for 1, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 30, 60 and 120min. Cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting with anti-phospho STAT-3 (Tyr705) Ab and anti-STAT (79D7) Ab. Recombinant human IL-11 induced STAT-3 phosphorylation in HBOCs at the indicated time points.

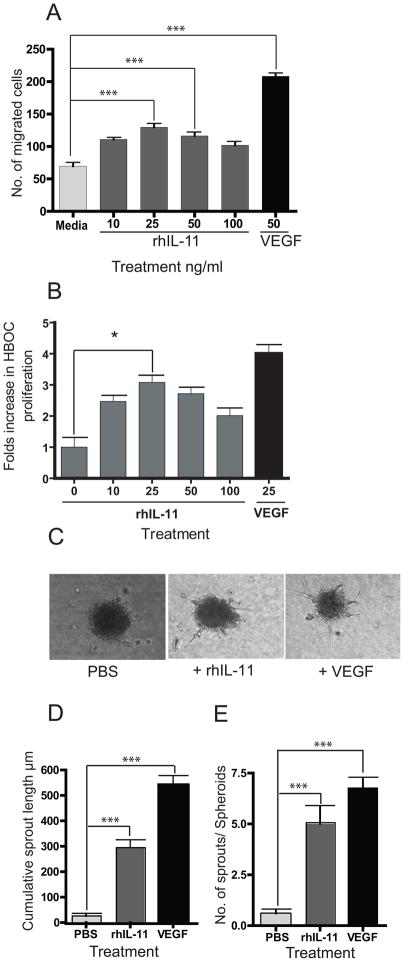

Recombinant human IL-11 stimulates directed migration and tubule formation in HBOCs

To study the physiologic effects of rhIL-11 on HBOCs, we administered rhIL-11 to HBOC in a Boyden chamber. Recombinant human IL-11 administration at 25ng/ml led to optimal cell migration of HBOCs towards a concentration gradient of rhIL-11 when compared to control (Figure 2A). Similarly, treatment of HBOC with 25 ng/ml of rhIL-11 resulted in 3-fold increase in HBOC proliferation (Figure 2B). Since cell migration and cell proliferation are cellular events that support blood vessel assembly, we performed a spheroid assay using HBOCs that were stimulated with rhIL-11 (Figure 2C) and counted the cumulative sprout length and total number of sprouts for each spheroid. As shown in Figures 2D and E, rhIL-11-treated HBOCs showed 11-fold increase in cumulative sprout length (Figure 2D) and 8-fold increase in sprouts/spheroids (Figure 2E) when compared to HBOCs treated with PBS control. These observations indicate that rhIL-11 enhances in vitro migration and proliferation of HBOCs and suggests a potential role of rhIL-11 for in vivo mobilization of CD34+/VEGFR2+ cells to sites of vascular remodeling.

Figure 2. Effects of rhIL-11 on migration and proliferation of HBOC.

A. HBOCs were analyzed in a Boyden Chamber with media, rhIL-11 or VEGF at the indicated concentrations. B. HBOC cells treated with rhIL-11 show a 3-fold increase in HBOC cell proliferation compared to control cells. C. Images of collagen embedded HBOC spheroids demonstrate sprouting after 24hrs of treatment with media, rhIL-11 or VEGF. D. Recombinant human IL-11 treatment leads to 11-fold increase in the cumulative sprout length, compared to media-treated control. E. Treatment with rhIL-11 results in 8-fold increase in the number of sprouts per spheroid. Each bar in the graphs represents the mean of three independent experiments. Unpaired t-test for rhIL-11 vs PBS treated mice, two-tailed *= P< 0.05, ***=P< 0.0001.

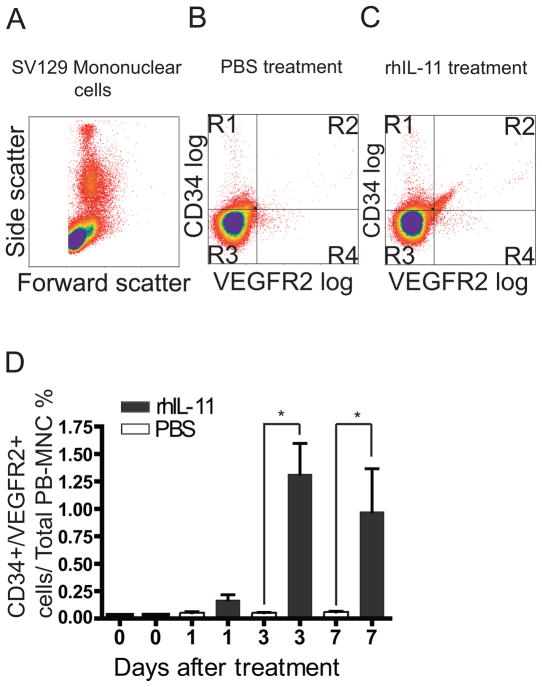

Recombinant human IL-11 treatment leads to in vivo mobilization of CD34+/VEGFR2+ mononuclear cells

Having already demonstrated that HBOCs express CD34+/VEGFR2+ markers in vitro, we next investigated the potential role of rhIL-11 on in vivo mobilization of CD34+/VEGFR2+ mononuclear cells by implanting Sv129 mice with osmotic pumps that continuously delivers 200 μg/kg/day of rhIL-11 or PBS. This dose resulted in maximum in vivo mobilization of CD34+/VEGFR2+ mononuclear cells (data not shown). Blood was drawn 1, 3 and 7 days after mini-pump implantation for characterization of mononuclear cells by flow cytometry. Figure 3A illustrates mononuclear cells profiled according to their forward and side scatter. Mice treated with rhIL-11 had a significantly higher percentage of cells in the R2 quadrant (1.3% of total peripheral blood mononuclear cells), which contained cells expressing both CD34+ and VEGFR2+ surface markers (Figure 3C and Supplemental Figure 1 and 2), compared with mice treated with PBS (Figure 3B). Seventy-two hours after rhIL-11 administration, there was a 20-fold increase in the number of circulating CD34+/VEGFR2+ cells (Figure 3D), compared with PBS-treated mice. By comparison, we observed a 2.8-fold increase in circulating platelet and a 2.5-fold increase in monocytes, and we did not observe a significant change in red blood cells, total white blood cells, lymphocytes or granulocytes (supplemental figure 3). This data provided the basis for further physiologic characterization of rhIL-11.

Figure 3. Mice treated with rhIL-11 have in-vivo mobilization of CD34+/VEGFR2+ mononuclear cells.

Sv129 mice were implanted with osmotic pumps loaded with either PBS or rhIL-11 for 3 days. A. Mononuclear cells from the mouse blood were analyzed by flow cytometry and profiled according to their forward and side scatter. PBS treated mice showed fewer CD34+/VEGFR2+ mononuclear cells in the R2 quadrant (B) compared with rhIL-11 treated mice (C) under the same experimental condition. D. CD34+/VEGFR2+ mononuclear cell-mobilization peaked 3 days after rhIL-11 treatment, with rhIL-11-treated mice exhibiting a 20-fold increase in circulating CD34+/VEGFR2+ mononuclear cells compared with PBS control mice on day 3. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of 6 mice. Unpaired student t-test, two tailed *= P< 0.05.

Recombinant human IL-11 increases recovery of perfusion after femoral artery ligation

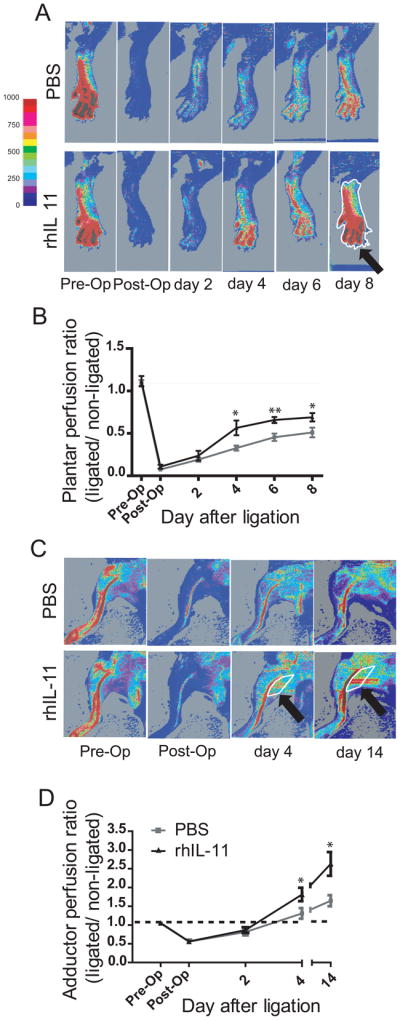

We used a model of hindlimb ischemia in which the right femoral artery is ligated proximal to the origin of the lateral caudal femoral artery. High-resolution infrared laser Doppler perfusion imaging with 2 millimeter sampling depth was then used to measure perfusion in the plantar foot (which is dependent on collateral vessels in the thigh and is a good index of overall leg perfusion 17, 22–24) and in the adductor region. Blood flow dropped to low values in both PBS-and rhIL-11-treated mice immediately after ligation (“Post-Op”) and continued to be decreased in both groups of animals 2 days later (Figure 4A, B and C), confirming successful femoral artery ligation in both animal groups. In addition, the lack of significant difference in blood flow between PBS- and rhIL-11-treated animals at these time points suggests that rhIL-11 does not have an acute effect on post-occlusive reperfusion. However, when examined at 4, 6 and 8 days following ligation, a greater recovery of plantar perfusion was seen in rhIl-11-treated mice when compared with syngeneic mice treated with PBS (Figure 4A and B and Supplemental Figure 4 A). In addition, rhIL-11-treated mice exhibited a greater increased measure of perfusion in the center of the adductor region, which contains collaterals interconnecting the saphenous and popliteal artery trees with medial trees branching from the femoral and iliac arteries proximal to the lateral circumflex femoral artery (Figure 4C and D and Supplemental Figure 4 B)17, 22, 24. Together, these observations suggest that rhIL-11 augments pre-existing collateral vessel remodeling.

Figure 4. Recombinant human IL-11-treated mice show faster recovery of perfusion.

Sv129 mice were pre-treated with rhIL-11 or PBS for 72 hours prior to femoral artery ligation. A. Laser Doppler perfusion imaging of the plantar foot of rhIL-11 treated mice showed increased plantar perfusion and faster blood flow recovery compared with PBS control mice. B. Graph showing ratio of perfusion rate in ligated/non-ligated plantar foot. Recombinant human IL-11 treated mice have significantly increased perfusion rates from day 4 to day 8 after femoral artery ligation. Each time point denotes mean ± SEM of 9 mice. Unpaired student T-test, two tailed *= P< 0.05, **= P< 0.01. Typical region of interest (ROI) used to calculate perfusion rate is marked in white (arrow). C. Laser Doppler perfusion imaging of the adductor region. Increased perfusion through the collaterals in the superficial gracilis muscle is evident on day 4 and 14 in the rhIL-11-treated animal. D. Graph showing ratio of perfusion rate in ligated/non-ligated adductor region. Color scale shows relation between color and units of perfusion rate.

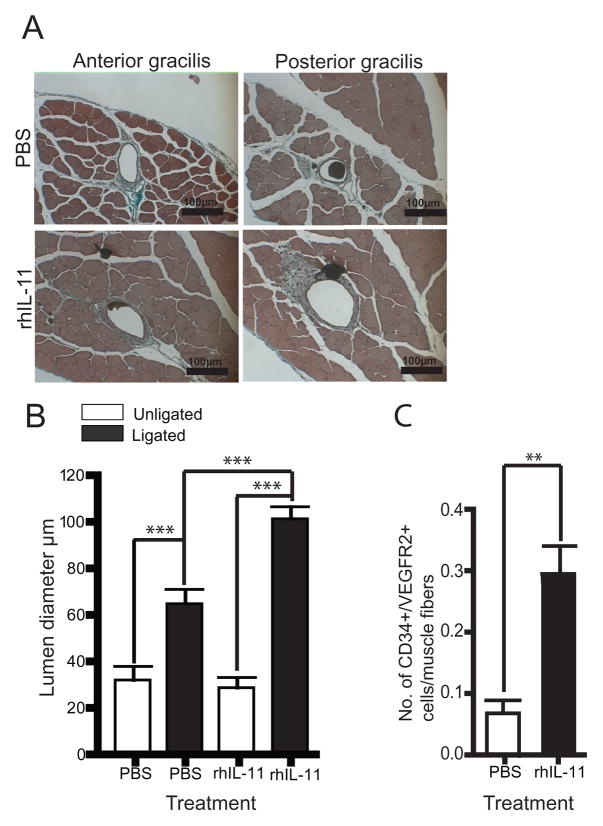

Recombinant human IL-11 improves functional recovery and collateral vessel growth

In order to determine the functional significance of the observed increase in reperfusion described above, we utilized a hindlimb use score (index of hindlimb muscle function) and appearance score (index of hindlimb ischemia)17, 22, 24 and discovered that rhIL-11-treated mice exhibited better hindlimb use and appearance scores than their PBS-treated counterparts (Supplemental Figure 5 A and B). To measure pre-existing collateral vessel remodeling directly, we performed histomorphometry of the single collateral present in each of the anterior and posterior gracilis muscles at 8 and 21 days after femoral artery ligation. Mice treated with rhIL-11 showed a 1.5-fold increase in collateral vessel luminal diameter on day 8 (data not shown) and a 3-fold increase in collateral vessel luminal diameter on day 21 after femoral artery ligation (Figure 5A and B), compared to PBS control mice, indicating that rhIL-11 plays a significant role in time-dependent collateral vessel growth. By comparison, we did not observe a difference in angiogenesis measured by isolectin B4+ cell analysis 21 days after femoral artery ligation (Supplemental Figure 6).

Figure 5. Mice treated with rhIL-11 have increased collateral vessel luminal diameter and influx of perivascular CD34+/VEGFR2+ cells.

A. Cyano-Masson-Elastin staining of anterior and posterior gracilis muscle showing increased collateral vessel luminal diameter in rhIL-11-treated mice 21 days after femoral artery ligation. B. Graph showing that rhIL-11-treated mice have a 3-fold increase in luminal diameter of adductor collateral vessel compared to PBS control. Each bar depicts mean ± SEM of 9 mice. Unpaired student t-test ***=P< 0.0001 (20 × magnification). C. Anterior and posterior gracilis muscle were stained for influx of perivascular CD34+/VEGFR2+ cells. Mice treated with rhIL-11 have 4.4-fold increase in perivascular CD34+/VEGFR2+ cells 8 days after femoral artery ligation. Each bar depicts mean ± SEM of 8 mice. Unpaired student T-test, two tailed **= P< 0.01.

Recombinant human IL-11 enhances influx of CD34+/VEGFR2+ mononuclear cells into perivascular tissues

Since we observed a 20-fold increase in circulating CD34+/VEGFR2+ cells associated with rhIL-11 treatment (Figure 3), we hypothesized that rhIL-11-mediated collateral vessel growth is functionally linked to mobilized CD34+/VEGFR2+ mononuclear cells. To examine this further, we performed immunohistochemical analysis of the anterior and posterior gracilis muscle to identify CD34+/VEGFR2+ mononuclear cells in the perivascular tissues 8 days after femoral artery ligation. As shown in Figure 5C and Supplemental Figure 7 A, mice treated with rhIL-11 displayed a 4.4-fold increase in perivascular CD34+/VEGFR2+ mononuclear cells when compared to control mice. By comparison, we only observed 2.6-fold increase in perivascular CD11b cells after rhIL-11 treatment (supplementary figure 7 B and C). Taken together, these data suggest that rhIL-11 enhances collateral vessel growth by augmentation of the influx of CD34+/VEGFR2+ and CD11b+ mononuclear cells into perivascular tissues.

Discussion

Although native collateral vessels are functional after vessel occlusion, they are often not well developed in acute or chronic vessel occlusion, resulting in significantly lowered chances of clinical improvement in symptoms. The clinical utility of mononuclear cells for adjunctive treatment of patients with PVD is based on the ability of mononuclear cells to revascularize occluded vessels by growth of pre-existing collaterals. Current methods of delivering mononuclear progenitor cells to patients with PVD include intramuscular injection of ex-vivo-processed bone marrow-derived or apheresed peripheral blood-derived mononuclear cells into the ischemic limb 25. These methods of mononuclear cell delivery are cumbersome, invasive, and associated with clinically significant procedural complications. Therefore, identification of a simple, less invasive strategy of revascularization by in vivo mobilization of progenitor cells is crucial to successful treatment of patients with PVD.

In this report, we describe a novel role for rhIL-11 on in vivo mobilization of CD34+/VEGFR2+ mononuclear cells and augmentation of collateral vessel growth after femoral artery ligation. We observed that rhIL-11 treatment led to a 20-fold increase in circulating CD34+/VEGFR2+ mononuclear cells and that mobilized CD34+/VEGFR2+ cells home into sites of collateral vessel remodeling resulting in collateral vessel growth and faster recovery of perfusion to ischemic limb in a manner that closely correlated with mobilization of CD34+/VEGFR2+ cells. These observations suggest that rhIL-11-mobilized CD34+/VEGFR2+ mononuclear cells, in part, participate in collateral vessel growth and is consistent with other reports showing a correlation between circulating CD34+ cells and the extent of collateral vessel remodeling during cerebral26 or hindlimb ischemia 27 in human and augmentation of regional blood flow and neovascularization 28 during cerebral or hindlimb ischemia in mice 29, 30.

Our histologic analysis of anterior and posterior gracilis muscle shows an increase in the luminal diameter of collateral vessels that was significant (1.5-fold) 8 days after femoral artery ligation and more pronounced (3-fold) 21 days after femoral artery ligation (Figures 5A and B). This is finding complements our laser Doppler perfusion imaging data showing faster recovery of plantar and adductor perfusion in rhIL-11-treated mice as early as four days after femoral artery ligation (Figure 4 and Supplemental Figure 4).

The mechanism of rhIL-11-mediated collateral vessel growth is an important topic of future study. Our data suggest that it is likely related to rhIL-11-induced circulating CD34+/VEGFR2+ mononuclear cells that are recruited to the perivascular ischemic region of the hindlimb where they may release cytokines/growth factors (paracrine effect) 31, activate STAT-3-dependent pathways (Supplemental Figure 8) and result in a reduction of apoptosis-mediated cell death (Supplemental Figure 9) as has been shown by others 32. Since monocytes and platelets have been previously shown to be involved in collateral vessel growth 33–35, our data suggest that CD34+/VEGFR2+ cells are candidate cells that also play a role in collateral vessel growth. We did not characterize the relative contribution of each of the above cells to the observed collateral vessel growth, and we cannot exclude the possibility that the observed effects are direct effects rhIL-11. Due to these limitations, additional studies using chimeric mice with tissue and/or cellular depletion of IL-11 will be necessary for further characterization of this mechanism.

In summary, this report shows that rhIL-11 treatment leads to in vivo mobilization of CD34+/VEGFR2+ mononuclear cells in mice. Pre-treatment of Sv129 mice with rhIL-11 prior to femoral artery ligation leads to an increase in collateral vessel growth and faster recovery of perfusion, which correlates with functional recovery of hindlimb use. Since rhIL-11 has been used for the treatment of other human diseases, this report suggests the possibility that rhIL-11 could be used as adjunctive treatment for patients with PVD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kirk McNaughton (University of North Carolina Histology Research Core Facility, Department of Cell and Molecular Physiology) for assistance in preparing tissue specimens. We thank Dr. Robert Bagnell (Microscopy Services Laboratory of the University of North Carolina Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine) for assistance with microscopy.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by NIH K08HL085293 and AHA 09BGIA2260549 grants(J.A.), NIH R01HL065619, PO1 AG 024282 and CDC H75DP001750 grants (C.P.) and NIH 090655 and 062584 grants (J.E.F.).

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose

References

- 1.Golomb BA, Dang TT, Criqui MH. Peripheral Arterial Disease: Morbidity and Mortality Implications. Circulation. 2006;114:688–699. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.593442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arain F, Cooper LT. Peripheral Arterial Disease: Diagnosis and Management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:944–950. doi: 10.4065/83.8.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tateishi-Yuyama E, Matsubara H, Murohara T, Ikeda U, Shintani S, Masaki H, Amano K, Kishimoto Y, Yoshimoto K, Akashi H, Shimada K, Iwasaka T, Imaizumi T. Therapeutic angiogenesis for patients with limb ischaemia by autologous transplantation of bone-marrow cells: a pilot study and a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2002;360:427–435. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09670-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saigawa T, Kato K, Ozawa T, Toba K, Makiyama Y, Minagawa S, Hashimoto S, Furukawa T, Nakamura Y, Hanawa H, Kodama M, Yoshimura N, Fujiwara H, Namura O, Sogawa M, Hayashi J-i, Aizawa Y. Clinical Application of Bone Marrow Implantation in Patients With Arteriosclerosis Obliterans, and the Association Between Efficacy and the Number of Implanted Bone Marrow Cells. Circulation Journal. 2004;68:1189–1193. doi: 10.1253/circj.68.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin Y, Weisdorf DJ, Solovey A, Hobbel RP. Origins of circulating endothelial cells and endothelial outgrowth from blood. JCI. 2000;105:71–77. doi: 10.1172/JCI8071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veleva AN, Stuart L, Patterson C. Selection and initial characterization of novel peptide ligands that bind specifically to human blood outgrowth endothelial cells. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2007;98:306–312. doi: 10.1002/bit.21420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zurita AJ, Troncoso P, Cardo-Vila M, Logothetis CJ, Pasqualini R, Arap W. Combinatorial Screenings in Patients: The Interleukin-11 Receptor {alpha} as a Candidate Target in the Progression of Human Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:435–439. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du X, Williams DA. Interleukin-11: a multifunctional growth factor derived from the hematopoietic microenvironment. Blood. 1994;83:2023–2030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du X, Williams DA. Interleukin-11: Review of Molecular, Cell Biology, and Clinical Use. Blood. 1997;89:3897–3908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirkiles-Smith NC, Mahboubi K, Plescia J, McNiff JM, Karras J, Schechner JS, Altieri DC, Pober JS. IL-11 Protects Human Microvascular Endothelium from Alloinjury In Vivo by Induction of Survivin Expression. J Immunol. 2004;172:1391–1396. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.3.1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahboubi K, Li F, Plescia J, Kirkiles-Smith NC, Mesri M, Du Y, Carroll JM, Elias JA, Altieri DC, Pober JS. Interleukin-11 Up-Regulates Survivin Expression in Endothelial Cells through a Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription-3 Pathway. Lab Invest. 2001;81:327–334. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waxman AB, Mahboubi K, Knickelbein RG, Mantell LL, Manzo N, Pober JS, Elias JA. Interleukin-11 and Interleukin-6 Protect Cultured Human Endothelial Cells from H2O2-Induced Cell Death. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;29:513–522. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0044OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon MS, McCaskill-Stevens WJ, Battiato LA, Loewy J, Loesch D, Breeden E, Hoffman R, Beach KJ, Kuca B, Kaye J, Sledge GW., Jr A phase I trial of recombinant human interleukin-11 (neumega rhIL-11 growth factor) in women with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy. Blood. 1996;87:3615–3624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tepler I, Elias L, Smith JW, 2nd, Hussein M, Rosen G, Chang AY, Moore JO, Gordon MS, Kuca B, Beach KJ, Loewy JW, Garnick MB, Kaye JA. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of recombinant human interleukin- 11 in cancer patients with severe thrombocytopenia due to chemotherapy. Blood. 1996;87:3607–3614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Timmermans F, Plum J, Yoder MC, Ingram DA, Vandekerckhove B, Case J. Endothelial progenitor cells: identity define? J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:87–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00598.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chakroborty D, Chowdhury UR, Sarkar C, Baral R, Dasgupta PS, Basu S. Dopamine regulates endothelial progenitor cell mobilization from mouse bone marrow in tumor vascularization. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2008;118:1380–1389. doi: 10.1172/JCI33125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chalothorn D, Clayton JA, Zhang H, Pomp D, Faber JE. Collateral density, remodeling, and VEGF-A expression differ widely between mouse strains. Physiol Genomics. 2007;30:179–191. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00047.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Urbich C, Dimmeler S. Endothelial Progenitor Cells: Characterization and Role in Vascular Biology. Circ Res. 2004;95:343–353. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000137877.89448.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duda DG, Cohen KS, Scadden DT, Jain RK. A protocol for phenotypic detection and enumeration of circulating endothelial cells and circulating progenitor cells in human blood. Nat Protocols. 2007;2:805–810. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Povsic TJ, Zavodni KL, Kelly FL, Zhu S, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ, Dong C, Peterson ED. Circulating Progenitor Cells Can Be Reliably Identified on the Basis of Aldehyde Dehydrogenase Activity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:2243–2248. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu H, Kortylewski M, Pardoll D. Crosstalk between cancer and immune cells: role of STAT3 in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:41–51. doi: 10.1038/nri1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chalothorn D, Zhang H, Clayton JA, Thomas SA, Faber JE. Catecholamines augment collateral vessel growth and angiogenesis in hindlimb ischemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H947–959. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00952.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Degenfeld G, Banfi A, Springer ML, Wagner RA, Jacobi J, Ozawa CR, Merchant MJ, Cooke JP, Blau HM. Microenvironmental VEGF distribution is critical for stable and functional vessel growth in ischemia. FASEB J. 2006;20:2657–2659. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6568fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clayton JA, Chalothorn D, Faber JE. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-A Specifies Formation of Native Collaterals and Regulates Collateral Growth in Ischemia. Circ Res. 2008;103:1027–1036. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.181115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al Mheid I, Quyyumi AA. Cell Therapy in Peripheral Arterial Disease. Angiology. 2009;59:705–716. doi: 10.1177/0003319708321584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshihara T, Taguchi A, Matsuyama T, Shimizu Y, Kikuchi-Taura A, Soma T, Stern DM, Yoshikawa H, Kasahara Y, Moriwaki H, Nagatsuka K, Naritomi H. Increase in circulating CD34-positive cells in patients with angiographic evidence of moyamoya-like vessels. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:1086–1089. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kudo F, Nishibe T, Nishibe M, Yasuda K. Autologous transplantaion of peripheral blood endothelial progenitor cells (CD34+) for therapeutic angiogenesis in patients with critical limb ischemia. Int Angiol. 2003;22:344–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taguchi A, Matsuyama T, Moriwaki H, Hayashi T, Hayashida K, Nagatsuka K, Todo K, Mori K, Stern DM, Soma T, Naritomi H. Circulating CD34-Positive Cells Provide an Index of Cerebrovascular Function. Circulation. 2004;109:2972–2975. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133311.25587.DE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taguchi A, Ohtani M, Soma T, Wantanabe M, Kinosita N. Therapeutic angiogenesis by autologous bone-marrow transplantation in a general hospital setting. Endovasc Surg. 2003;25:276–278. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2002.1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schatteman GC, Hanlon HD, Jiao C, Dodds SG, Christy BA. Blood-derived angioblasts accelerate blood-flow restoration in diabetic mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:571–578. doi: 10.1172/JCI9087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kong D, Melo LG, Gnecchi M, Zhang L, Mostoslavsky G, Liew CC, Pratt RE, Dzau VJ. Cytokine-Induced Mobilization of Circulating Endothelial Progenitor Cells Enhances Repair of Injured Arteries. Circulation. 2004;110:2039–2046. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143161.01901.BD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Obana M, Maeda M, Takeda K, Hayama A, Mohri T, Yamashita T, Nakaoka Y, Komuro I, Takeda K, Matsumiya G, Azuma J, Fujio Y. Therapeutic Activation of Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 by Interleukin-11 Ameliorates Cardiac Fibrosis After Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. 2010;121:684–691. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.893677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arras M, Ito WD, Scholz D, Winkler B, Schaper J, Schaper W. Monocyte activation in angiogenesis and collateral growth in the rabbit hindlimb. JCI. 1998;101:40–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI119877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ito WD, Arras M, Winkler B, Scholz D, Schaper J, Schaper W. Monocyte Chemotactic Protein-1 Increases Collateral and Peripheral Conductance After Femoral Artery Occlusion. Circ Res. 1997;80:829–837. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.6.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buschmann I, Schaper W. Arteriogenesis Versus Angiogenesis: Two Mechanisms of Vessel Growth. News Physiol Sci. 1999;14:121–125. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.1999.14.3.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.