Abstract

Forkhead box O (FOXO) transcription factors have been implicated in regulating the metabolism, cellular proliferation, stress resistance, apoptosis, and longevity. Through the insulin receptor substrate → phosphoinositide 3-kinase → Akt signal cascade, FOXO integrates insulin action with the systemic nutrient and energy homeostasis. Activation of FOXO1 in liver induces gluconeogenesis via phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK)/glucose 6-phosphate pathway, and disrupts mitochondrial metabolism and lipid metabolism via heme oxygenase 1/sirtuin 1/Ppargc1α pathway. In skeletal muscle, FOXO1 activation underpins the carbohydrate/lipid switch during fasting state. Inhibition of FOXO1 under physiological conditions accounts for maintenance of skeletal muscle mass/function and adipose differentiation. In pancreatic β-cells, nuclear translocation of FOXO1 antagonizes pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1 and attenuates β-cells proliferation and insulin secretion. Regardless, FOXO1 promotes the proliferation of β-cells through induction of Cyclin D1 in low nutrition, and elicits antioxidant mechanism to protect against β-cell failure during oxidative insults. In the brain, FOXO1 controls food intake through transcriptional regulation of the orexigenic neuropeptide Y, agouti-related protein, and carboxypeptidase E. In this article, we review the role of FOXO1 in the regulation of metabolism and energy expenditure based on recent findings from mouse models, and discuss the therapeutic value of targeting FOXO1 in metabolic diseases. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 14, 649–661.

Introduction

Since the initial discovery of the fly Drosophila melanogaster gene forkhead, over 100 members of this gene family have been identified, and 19 human subgroups are now known to exist (76, 90). The members of this gene family contain a conserved 100 amino acid forkhead box (also called winged helix DNA-binding domain). The superfamily is identified as “FOX,” whereas the 19 subfamilies are designated by a letter followed by a number to distinguish individual members (51). Forkhead box O (FOXO) subfamily consists of transcription factors (FOXO1, FOXO3, FOXO4, and FOXO6) that regulate expression of target genes involved in DNA damage repair response, apoptosis, metabolism, cellular proliferation, stress tolerance, and longevity (16, 104, 113, 115). The evidence from genetically generated mouse models has shown that these FOXO transcription factors have overlapping functions (functional redundancy) although individual disruption of the FOXO genes causes different phenotypes during development (functional diversification) (4, 5, 93, 106, 108).

FOXO plays a critical role in metabolism and growth of mammals (72, 90). FOXO is expressed ubiquitously in mammalian tissues, especially adipose, brain, heart, liver, lung, ovary, pancreas, prostate, skeletal muscle, spleen, thymus, and testis (77, 90). It is regulated by several mechanisms, including Akt (or protein kinase B [PKB])-mediated serine phosphorylation. During insulin stimulation, the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) → Akt cascade inhibits FOXO nuclear activity, which is characteristic of the postprandial state of nutrient excess. Whole-body glucose homeostasis is tuned by both endogenous glucose production and glucose uptake by peripheral tissues in response to insulin. FOXO1 is activated in the fasted state to promote gluconeogenesis in the liver, but in postprandial state hepatic FOXO1 is inhibited by insulin, which facilitates gene expression that drives the metabolism of glucose to acetate for oxidation or conversion into fatty acids (25, 117). FOXO-mediated gene expression has multiple effects upon lipid metabolism (18, 19, 53, 81). Insulin resistance leads to hyperactive FOXO transcriptional activity, and eventually induces hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia in mammals (12, 19, 38, 52, 118). In addition, activation of FOXO under insulin resistant conditions can result in muscle atrophy and impair adipose proliferation, which reduced the capacity of these tissues to respond to insulin stimulation (55, 78, 123). Genetic ablation of FOXO during insulin resistance is beneficial for metabolic homeostasis; however, under normal nutrition the deletion of hepatic FOXO has minimal effects (25, 82). These findings reveal FOXO transcription factors as potential therapeutic targets for metabolic syndromes associated with insulin resistance.

FOXO1 represents the predominant FOXO isoforms (35, 36, 90). In this review, we will review some recent research focusing mainly upon in mouse models. These studies reveal new strategies to understand the pathophysiology of metabolic diseases such as obesity, nonalcoholic fatty liver diseases, diabetes, and diabetic complications.

Regulation of FOXO

FOXO proteins contain 4 domains. Sequence alignment shows that these FOXO proteins have highly conserved regions, including the N-terminal region containing an Akt phosphorylation site, a highly conserved forkhead DNA binding domain (DBD), a nuclear localization signal located just downstream of DBD, a nuclear export sequence, and a C-terminal transactivation domain (92). The DBD domain contains 3 α-helices, 3 β-sheets, and 2 loops that are referred to as the wings. FOXO1, FOXO3, and FOXO6 have similar length of about 650 amino acid residues, whereas FOXO4 is shorter and contains about 500 amino acid residues. All the regulation mechanisms involve the retention of FOXO in the nucleus where it can promote or suppress the transcription of target genes containing a consensus DNA binding sequence—TTGTTTAC.

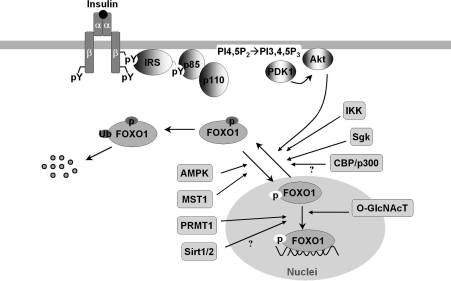

FOXO proteins are modified by several posttranslational modifications, including phosphorylation, acetylation, methylation, glycosylation, and ubiquinylation (Fig. 1) (reviewed in 92, 99, 119). The modifications affect protein–protein and protein–DNA interactions that eventually alter the DNA-binding characteristics of FOXO proteins and regulate their transcriptional activity (11, 92, 109, 110, 114, 119). For example, the serine-threonine kinase Akt can phosphorylate FOXO1, FOXO3a, and FOXO4 and exclude them from nucleus, which promotes cytoplasm ubiquitinylation and degradation. An exception to this nucleo-cytoplasmic trafficking is FOXO6 whose transcriptional activity is similarly blocked by Akt-phosphorylation but independent of shuttling to the cytosol (49, 112). Moreover, FOXO transcriptional activity is inhibited by inhibitor of NF-κB (nuclear factor κB) kinase and the serum/glucocorticoid-inducible protein kinase that cause phosphorylation and nuclear exclusion (76, 92); however, it can be enhanced by mammalian sterile 20-like kinase-1-induced phosphorylation (70) and AMP-activated protein kinase (34). Arginine methylation of FOXO blocks Akt-induced phosphorylation and inactivation (119). However, addition of O-linked β-N-acetyl-glucosamine to FOXO promotes expression of its target genes involved in stress resistance during hyperglycemia and cell stress (43, 44). Deacetylation of FOXO by sirtuin 1 (SirT1) was shown to suppress mammalian FOXO transcriptional factor (13, 86, 120), although some opposite evidence indicates that the lysine acetylation of FOXO increases FOXO phosphorylation and attenuate its ability to bind cognate DNA sequence (82a). Comprehensive review on the structure/posttranslational regulation of FOXO transcriptional factors can be found in this Forum issue of Antioxidants & Redox Signaling.

FIG. 1.

The posttranslational regulation of FOXO1. Hormonal and stress stimuli regulate FOXO1 via phosphorylation, acetylation, ubiquitination, methylation, and glucose-derived O-GlcNAc modification. The phosphorylation induced by Akt, Sgk, and IKK is inhibitory (dark gray), whereas MST1 and AMPK phosphorylate and activate FOXO1 (white background). Methylation of FOXO1 by arginine methyltransferase PRMT1 blocks Akt-mediated phosphorylation and thus promotes FOXO1 nuclear redistribution. The role of CBP-catalyzed acetylation and SirT1/2-catalyzed deacetylation in FOXO1 activity is controversial, being reported positive and negative, or vice versa, in the literature. O-GlcNAc regulates FOXO1 activation in response to glucose, resulting in paradoxically increased expression of gluconeogenic genes while concomitantly inducing expression of genes encoding enzymes that detoxify reactive oxygen species. Akt, protein kinase B; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; CBP, CREB (cAMP response element-binding) binding protein; FOXO, forkhead box O; IKK, IκB (inhibitor of NF-κB) kinase; IRS, insulin receptor substrates; MST1, mammalian sterile 20-like kinase-1; O-GlcNAc, O-linked β-N-acetyl-glucosamine; O-GlcNAcT = O-linked β-N-acetyl-glucosamine transferase; PDK1, 3-Phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1; PRMT1, protein arginine methyltransferase 1; Sgk, serum/glucocorticoid-inducible protein kinase; SirT1/2, sirtuin 1 or 2.

At the transcriptional level, expression of FOXO1 and FOXO3 can be induced by transcription factors E2F1 (91) and FOXC1 (10). Recent evidence shows that the transcription of FOXO is stimulated by FOXO3 in a positive feedback loop, but is repressed by growth factors such as platelet-derived growth factors and fibroblast growth factors (27). Ectopic FOXO3 activation blocked the proliferation of fibroblasts and induced expression of FOXO1 and FOXO4, mimicking the effects of growth factors. This regulatory mechanism may account at least in part for the coordinate upregulation of FOXO1, FOXO3, and FOXO4 in skeletal muscle from the mice treated by calorie restriction (20, 30). Moreover, the insulin receptor represses its own synthesis by a feedback mechanism directed by the transcription factor FOXO1 (97). These feedback loops, positive or negative, suggest that FOXO acts as a nutrient sensor to activate insulin (or growth factor) signaling that establishes an adaptive response to circulating factors.

FOXO1 in Regulation of Metabolism

FOXO1 is the best-studied member of FOXO subfamily. Loss and gain of FOXO1 function has been investigated in the tissues and cells of various genetically modified mice, including hepatocytes (18, 19, 25, 82), brain (95), muscle (20, 45, 55), adipose (17, 88), pancreas (2, 3, 84), and heart (99) (Table 1).

Table 1.

FOXO1 Regulation of Metabolism in Different Organs

| Organs | Biological effects of FOXO1 | References |

|---|---|---|

| Liver | Ablation of hepatic FOXO1 reverses the abnormalities existing in the mitochondrial metabolism, blood glucose and insulin concentrations, and body size of insulin-resistant mice. | (18, 25, 82, 101) |

| Muscle | Skeletal muscle FOXO1 transgenic mice have less skeletal muscle mass, downregulated type I fiber genes, and impaired glycemic control, but not longer life. | (20, 55) |

| Brain | FOXO1 deletion in pro-opiomelanocortin (Pomc)-expressing neurons protecting against weight gain and obesity. Mice selectively expressing a constitutively nuclear FOXO1 in Pomc neurons exhibit mild obesity and hyperphagia. | (48, 95) |

| Adipose | Adipose dominant-negative FOXO1 transgenic mice show improved glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity, with smaller-sized adipocytes in white adipose tissue (WAT) under a high-fat diet; had increased oxygen consumption in brown adipose tissue (BAT). | (88) |

| FOXO1 haploinsufficiency results in increased PPARγ gene expression in adipose tissue and protects mice against obesity-related insulin resistance. | (58) | |

| β-Cells | FOXO1 protects β-cells against oxidative stress by forming a complex with the promyelocytic leukemia protein PML and the NAD-dependent deacetylase SirT1 to activate expression of NeuroD and MafA. | (63) |

| FOXO1 may negatively regulate β-cell differentiation and proliferation in the human fetal pancreas by controlling PDX1, NGN3, and NKX6. | (1, 3) | |

| FOXO1 promotes the proliferation of β-cell exposed to low nutrition. | (2) |

FOXO, forkhead box O; NGN3, neurogenin 3; PDX1, pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1; PML, promyelocytic leukemia; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ; SirT1, sirtuin 1.

FOXO1 in Liver

The liver is the primary organ for glucose and lipid metabolism (96). During fasting, glycogen stored in hepatocytes is hydrolyzed to release glucose (glycogenolysis). Upon glycogen depletion, gluconeogenesis ensures a sufficient glucose supply through transcriptional modifications controlled by CREB (cyclic AMP-responsive element binding protein)-regulated transcription co-activator 2 and FOXO1 (74). In the postprandial state, the liver stores the dietary carbohydrates through glycogen synthesis and de novo lipogenesis (18, 25, 81, 118). Under ordinary conditions, the fasting-feeding switch finely controls the hepatic glucose production/uptake and anabolic pathways of glucose disposal, which restricts postprandial in plasma glucose concentrations between 4 and 7 mM. The critical role of FOXO1 in hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism is well established with genetically modified mice (18, 25, 53, 81, 82). However, a critical role for hepatic FOXO1 is difficult to demonstrate definitively without additional efforts to stress the animal, including severe starvation or deletion of insulin signaling components. By deletion of hepatic insulin receptor substrates 1 and 2 [i.e., the liver-specific Irs1 and Irs2 double knockout (DKO)-mice], the mice lose the conserved response to insulin/feeding, and develop severe insulin resistance and glucose intolerance (25, 37). Microarray of the transcriptome in DKO-liver reveals markedly perturbed expression of growth and metabolic genes, including increased Ppargc1α (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-α, also referred as Pgc1α) and Igfbp1, and decreased glucokinase, sterol-regulatory-element-binding protein 1c (SREBP-1c), Ghr, and Igf1 (25) (Fig. 2). Moreover, mitochondrial genes are dysregulated, which leads to abnormal mitochondrial morphology, function, and biogenesis in the DKO-liver (Table 2) (18). Signal transduction analysis indicates that FOXO1 is hyperactivated in these mice. Remarkably, expression of these genes is at least partially restored into a normal range upon deletion of FOXO1 (Fig. 3) (18, 25).

FIG. 2.

The effects of FOXO1 activation and ablation on gene expression in the liver. Normalized expression of liver genes was analyzed in fasted (16 h) and fed (4 h) 6-week-old control (CNTR), Irs1/2 double-knockout (DKO), and Irs1/2 and FOXO1 TKO mice using Affymetrix GeneChips. Liver genes that had been changed significantly (false discovery rate FDR <0.05) were further analyzed for either a positive (+) or negative (−) correlation with principal component using the NIA Array Analysis Tool. The analyses indicate that 9824 significantly changed probe sets corresponded to 5756 annotated genes of which 420 displayed a maximal change of at least 1.5-fold. The principal components (PC)—with a positively and negatively correlated gene cluster—accounted for 86% of the total expression variance, including 3531 displaying increased and 593 displaying decreased expression in the DKO liver. Dysregulated expression of these genes in the DKO liver was largely restored in the TKO liver to the normal range displayed by the control liver. Data were presented as average normalized expression (log2 scale) of gene clusters positively correlated (•) and negatively correlated (▪) with principal component. The error bars represent the standard deviation. Adapted from Dong et al. (25) with permission. TKO, triple knockout.

Table 2.

The Changes in Mitochondrial Gene Expression

| |

|

Median expression |

DKO |

TKO |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | n | CNTR | DKO | TKO | CNTR | CNTR |

| Dctn (p50) | 1 | 984 | 1411 | 916 | 1.4 | 0.9 |

| Dnm 1 (Drp 1) | 2 | 20 | 19 | 16 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| Fis1 | 2 | 421 | 635 | 393 | 1.5 | 0.9 |

| Hmox1 | 2 | 96 | 230 | 116 | 2.4 | 1.2 |

| Mfn1 | 2 | 227 | 453 | 212 | 2.0 | 0.9 |

| Mfn2 | 2 | 219 | 566 | 201 | 2.6 | 0.9 |

| Nrf1 | 3 | 71 | 81 | 73 | 1.2 | 1.0 |

| Ppargc1α | 1 | 115 | 1570 | 301 | 14 | 2.6 |

| Tfam | 2 | 200 | 309 | 226 | 1.5 | 1.1 |

Adapted from Cheng et al. (18) with permission.

CNTR, Control; DKO, double knockout; Hmox1, heme oxygenase 1; TKO, triple knockout.

FIG. 3.

The regulation of hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism by FOXO1. Under ordinary conditions, feeding stimulates insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells, and FOXO1 is inhibited by insulin signal via IRS-PI3K-Akt cascade. In fasting state, insulin signal is weak and FOXO1 is activated/translocated into the nuclei to trigger gluconeogenesis for glucose supply. Under insulin resistance conditions, however, hyperactive FOXO1 promotes gluconeogenesis in such an uncontrolled way that it leads to hyperglycemia. Moreover, FOXO1 induces Hmox1 that disrupts electron transport chain and impairs mitochondrial metabolism (including fatty acid oxidation). FOXO1 might also enhance downstream of insulin signal (increasing Akt phosphorylation) by acting on Trb3 and p38, which may eventually promote lipogenesis. Regardless, it remains unclear how insulin drives lipogenesis under insulin-resistant conditions when insulin fails to initiate the IR-IRS-PIK-Akt cascade. FA, fatty acid; FAO, fatty acid oxidation; G6P, glucose 6-phosphate; Hmox1, heme oxygenase 1; MTP, microsomal triglyceride transfer protein; PEPCK, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; SREBP-1c, sterol-regulatory element binding protein 1c; TG, triglyceride; Trb3, Tribbles homolog 3; VLDL, very-low-density lipoprotein.

Chronic failure to control the hepatic glucose production leads to hyperglycemia and compensatory stimulation of insulin secretion by the pancreatic β-cells, which exacerbates peripheral insulin resistance in muscle and adipose (25, 117, 118). Hepatocyte-specific deletion of FOXO1 in DKO mice (triple knockout TKO) results in significant normalization of the gluconeogenic genes and partial restoration of the response to fasting and feeding, near-normal blood glucose and insulin concentrations (25). Single knockout of FOXO1 in mouse liver results in 40% reduction of glucose levels at birth and 30% reduction in adult mice after a 48 h fast (82). These changes are associated with impaired fasting- and cAMP-induced glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, because the complex between FOXO1 and the transcription coactivator Ppargc1α is absent, which compromises the cAMP response and gluconeogenesis (82). Similarly, FOXO1 deletion in liver curtails excessive glucose production caused by ablation of hepatic insulin receptor and prevents neonatal diabetes and hepatosteatosis in liver-specific insulin receptor knockout mice (82, 85). These findings corroborate the deleterious role of the constitutively active FOXO1 in hyperglycemia during severe hepatic insulin resistance, and that the insulin receptor substrates (Irs1/2) → PI3K → Akt → FOXO1 branch of insulin signaling underpins the hepatic insulin-regulated glucose homeostasis (Fig. 3) (25, 82). To this end, synthetic and optimized antisense oligonucleotides for specific inhibition of FOXO1 expression (FOXO1-antisense oligonucleotide therapy) has been used to improve both hepatic and peripheral insulin action that lowers plasma glucose concentration and the rate of basal endogenous glucose production in mice with diet-induced obesity (DIO) (101).

The mechanism by which insulin resistance fails to inhibit FOXO1 → PEPCK driven gluconeogenesis (hyperglycemia) while promoting SREBP-1c-mediated lipogenesis (dyslipidemia) remains unclear (Fig. 3) (12, 65, 118). In this respect, identification of the branch/divergent point that insulin signal control glucose production and lipogenesis has been the topic of intensive study. The results from mice that lack both major regulatory subunits of PI3 kinase in the liver (Pik3r1 and Pik3r2; L-p85DKO mice) suggest that Akt and atypical protein kinase C differentially define specific actions of insulin and PI3 kinase on hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism, respectively (107). In the obese, insulin-resistant mice induced by either leptin deficiency or high-fat diet, Akt is required for hepatic lipid accumulation (67). Leptin-deficient obesity mice lacking hepatic Akt exhibit a decrease in lipogenic gene expression and de novo lipogenesis, which prevents hepatic triglyceride accumulation. Whereas mice fed high-fat diet have reduced liver triglycerides in the absence of hepatic Akt, lipogenesis progresses normally presumably due to a compensatory adaptation to the uptake of dietary fat. These findings reveal Akt as a requisite component in insulin-dependent regulation of lipid metabolism during insulin resistance (67). Further corroborating evidence was reported most recently, showing that inhibition of PI3 kinase → Akt blocks both insulin-mediated PEPCK (gluconeogenesis) and SREBP-1c (lipogenesis) gene expression (71). Inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), a downstream target of Akt can block insulin-induction of SREBP-1c but not insulin suppression of PEPCK, suggesting that insulin-mediated lipogenesis and gluconeogenesis diverge with Akt → mTORC1 driving the former and FOXO1 → PEPCK driving gluconeogenesis (Fig. 3); however, during severe insulin resistance FOXO appears to contribute to both processes (18, 19).

Hyperactivated FOXO during severe insulin resistance contributes to the accumulation of hepatic lipids (Fig. 3) (18, 19, 81). Adenoviral delivery of constitutively nuclear FOXO1 to mouse liver promotes hepatic triglyceride accumulation that can progress to steatosis (81). The lipid accumulation is associated with decreased fatty acid oxidation. Paradoxical stimulation of Akt signaling occurs owing to FOXO1-mediated repression of pseudokinase tribble 3 (a modulator of Akt activity) independent of DNA binding; however, suppression of FOXO1 with appropriate siRNA diminishes it (81). An accompanying study using constitutively nuclear FOXO1 (FOXO1-ADA mutant that is constitutively nuclear due to mutation of T24 and S316 to A and harbors a mutation of S253 to D) suggests that FOXO1 turns on a feed-forward loop, relayed by p38 and acting to amplify Akt activity (87). In addition, FOXO1 can induce expression of hepatic microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP) that regulates the rate-limiting step of assembly of triglyceride-rich very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) (53). FOXO1 gain of function is associated with enhanced MTP expression, correlating with augmented hepatic VLDL production and elevated plasma triglyceride levels in FOXO1 transgenic mice. FOXO1 loss of function, caused by RNAi-mediated depletion of FOXO1 mRNA in liver, reduces hepatic MTP and VLDL production in diabetic, db/db and FOXO1 transgenic mice. The stimulating effect of FOXO1 on MTP expression and VLDL production is blunted by insulin in the control mice (53).

In addition to regulation of lipogenesis, recent observations indicate that activated FOXO1 impairs fatty acid oxidation. By this mechanism, dyslipidemia might arise at least in part from mitochondrial dysfunction under the insulin-resistant conditions (Fig. 3) (18, 19, 81). In mice lacking hepatic Irs1/Irs2, FOXO1 hyperactivation is accompanied by impaired mitochondrial oxidative metabolism and mild hepatic lipid accumulation (18, 19). By directly binding the promoter, the transcription factor FOXO1 induces heme oxygenase 1 that reduces the heme content/pool required for expression, stability, and function of electron transport chain (ETC) components (18, 21). The impaired ETC activity in these DKO hepatocytes fails to oxidize NADH to NAD+, thus decreasing the [NAD+]/[NADH] ratio due to NADH accumulation. These changes prevent 2 biological processes that are related to NADH metabolism and [NAD+]/[NADH] ratio (18, 19). First, the NAD+-dependent deacetylase SirT1 is inactivated, which blocks the mitochondrial biogenesis pathway mediated by Ppargc1α—the activation of Ppargc1α requires SirT1-catalyzed deacetylation. Second, NAD+ acts as the essential cofactor of acyl-CoA dehydrogenase in fatty acid oxidation. Reduction of [NAD+] due to ETC defects attenuates fatty acid oxidation, which promotes accumulation of fatty acid available for incorporated into triglyceride (46, 47, 100, 116). As such, pharmacological stimulation of NADH oxidation strongly promotes mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and attenuates dyslipidemia and fatty liver in DIO and ob/ob mice (46). In line with the observation that adenoviral delivery of constitutively nuclear FOXO1 to mouse liver decreased fatty acid oxidation (18, 19, 81), targeting hepatic FOXO1 by anti-sense oligonucleotides or knockout lowers both hepatic triglyceride and diacylglycerol content, which is at least in part accounted for by the restoration of mitochondrial function (18, 19, 101).

Together, activated FOXO1 promotes hepatic glucose production through induction of the gluconeogenic enzymes, PEPCK and glucose 6-phosphate. FOXO1 may also participate in lipid metabolism by driving Akt-mediated lipogenesis through p38 and tribbles homolog 3. Under insulin-resistant conditions, the induction of heme oxygenase 1 that cause ETC defects results in impaired mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and lipid accumulation. Hyperactive FOXO1 under insulin-resistant conditions causes hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia, the characteristics of diabetes and diabetic complications. Therefore, finely tuned FOXO1 activity is the premise of nutrient and metabolic homeostasis.

FOXO1 in Brain

FOXO1 is strongly expressed in the striatum and neuronal subsets of the hippocampus (dentate gyrus and the ventral/posterior part of the cornu ammonis regions) (41). In wild-type mice, hypothalamic FOXO1 expression is reduced by the anorexigenic hormones insulin and leptin (59). Deletion of Irs2 in the brain activates FOXO1 that accounts for extended life span of mice (106). After the observation that neuron-specific insulin receptor knockout mice developed diet-sensitive obesity with increases in body fat and plasma leptin levels (14), FOXO1 as the downstream target was recently found to play the key role in control food intake, energy disposal, and fuel metabolism (9, 48, 59, 60, 95). The adenoviral delivery of a constitutively active FOXO1 to the hypothalamus disables leptin to control food intake, and the mice showed an increased food intake and body weight (59, 60). Mechanistic studies indicate that FOXO1 stimulates the transcription of the orexigenic neuropeptide Y and agouti-related protein via PI3 kinase → Akt cascade, but suppresses the transcription of anorexigenic pro-opiomelanocortin (Pomc) by antagonizing the activity of signal transducer-activated transcript-3 (STAT3) (59, 60). Given that both insulin and leptin signaling pathways converge on PI3 kinase → 3-Phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1) → Akt → FOXO1 in (Pomc) neurons, 2 independent groups confirmed that Pomc neuron-specific PDK1 knockout (PDK1ΔPomc) mice display hyperphagia, increased body weight, and impaired glucose metabolism caused by reduced hypothalamic Pomc expression (9, 48). Selective expression of a transactivation-defective FOXO1 mutant in Pomc cells ameliorates the energy imbalance in PDK1ΔPomc mice (9), whereas expression of a constitutively nuclear FOXO1 exacerbated the obesity of the PDK1ΔPomc mice due to excessive suppression of the Pomc gene (48).

Recently, ablation of Pomc-FOXO1 identified carboxypeptidase E (Cpe) as a critical downstream component in the dysregulation of food intake and energy expenditure (95). Cpe expression increases during the deletion of Pomc-FOXO1, which is concomitant with decreased food intake and normalized energy expenditure. Of note, Cpe expression is downregulated by DIO, but Pomc-FOXO1 ablation prevents Cpe downregulation and protects against weight gain. Moderate Cpe overexpression in the arcuate nucleus phenocopies features of the FOXO1 mutation (95). These findings suggest that targeting Pomc-FOXO1 can be a model for therapeutic intervention in obesity.

Thus, FOXO1 in brain appears to be a dysregulating factor of leptin/insulin-mediated food intake/energy expenditure. Persistently activated FOXO1 increases food intake and predisposes to obesity. Inhibition of FOXO1 dampens neuropeptide Y and agouti-related protein, but promotes Cpe expression, which ameliorates metabolic disorder and protects against weight gain.

FOXO1 in Skeletal Muscle

The skeletal muscle is one of the major peripheral tissues that are responsible for insulin-mediated fuel metabolism and energy expenditure. Skeletal muscle accounts for >30% of resting metabolic rate and 80% of whole-body glucose uptake (23). Expression of FOXO1 is increased in skeletal muscle by energy deprivation (such as fasting, calorie restriction, and severe diabetes), suggesting that FOXO1 may mediate the response of skeletal muscle to changes in energy metabolism (20, 29, 56). Indeed, FOXO1 suppresses SREBP-1c in skeletal muscle (54), and mice overexpressing FOXO1 lose their glycemic control and display a lower capacity for physical exercise due to severe muscle loss (55).

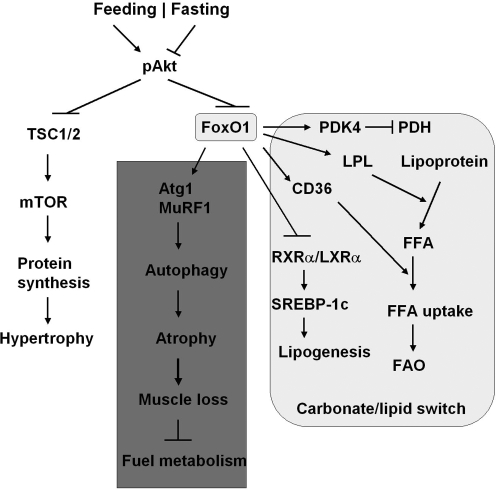

Skeletal muscle metabolism switches from oxidation of carbohydrates to fatty acids as the major energy source during fasting when the plasma glucose concentration is low. FOXO1 controls this switch by upregulating 3 enzymes: pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase-4 (PDK4) that shuts down glucose oxidation by targeting pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), lipoprotein lipase that hydrolyzes plasma triglycerides into fatty acids, and fatty acid translocase CD36 that facilitates fatty acid uptake into skeletal muscle (Fig. 4) (8, 29). PDK4 phosphorylates PDH and blocks PDH activity in catalyzing the conversion of pyruvate into acetyl-CoA, which can divert glucose flux to lactate and away from acetyl-CoA (8, 29). During starvation or glucocorticoid treatment, FOXO1 expression increases and directly induces PDK4 expression to inhibit glucose oxidation (29). In the mean time, FOXO1 overexpression in muscle C2C12 cells enhances lipoprotein lipase gene expression and increases the plasma membrane level of the fatty acid translocase CD36. These changes promote the membrane uptake of oleate and oleate oxidation (8, 56). FOXO1 also regulates triglyceride content via retinoid X receptor α (RXRα)/liver X receptor α (LXRα)/SREBP-1c pathway (54). FOXO1 suppresses RXRα/LXRα/-mediated SREBP-1c promoter activity: gene expression of both RXRγ and SREBP-1c is downregulated in skeletal muscle FOXO1 transgenic mice (Fig. 4). During nutritional changes caused by fasting and feeding, gene expression of RXRα and SREBP-1c in mouse skeletal muscle switches off and on, respectively, whereas expression of FOXO1 shows reverse correlation with SREBP-1c expression (54).

FIG. 4.

Metabolic regulation by FOXO1 in skeletal muscle. Under feeding state FOXO1 is inactivated, and insulin drives protein synthesis through Akt-TSC1/2-mTOR pathway. In fasting states, FOXO1 induces PDK4 that inhibits PDH and blunts glycolysis (pyruvate → tricarboxylic acid cycle). On the other hand, FOXO1 induces LPL and CD36: the former promoting the hydrolysis of lipoprotein into FFA, and the latter promoting the FFA uptake by muscle cells. Moreover, FOXO1 disrupts the RXRα/LXR(complex and the downstream SREBP-1c-mediated lipogenesis in muscle cells. Thus, FOXO1 plays a key role in the carbohydrate/lipid metabolic switch in skeletal muscle during fasting/feed cycle. Under insulin resistance conditions, FOXO1 is hyperactivated and induces autophagy-related proteins degradation through Atp1 and MuRF1, which causes atrophy (muscle loss) and disturbs metabolic homeostasis. Atg1, atrogin 1 (F-box protein 32); FFA, free fatty acid; LPL, lipoprotein lipase; LXRα, liver X receptor α; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; MuRF1, muscle-specific RING finger protein 1; PDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase; PDK4, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4; RXRα, retinoid X receptor α; TSC1/2, tuberous sclerosis complex 1 and 2.

The muscle mass/fiber size is known to change with workload, activity, or pathological conditions, including diabetes mellitus. The maintenance of muscle mass is achieved by a dynamic balance of atrophy and hypertrophy (32, 102). Activation of FOXO1 or FOXO3 in the skeletal muscle, in fasting or diabetic conditions, can increase protein breakdown through ubiquitin-proteasome and autophagy-lysosome pathways, the 2 major mechanisms causing muscle atrophy (Fig. 4) (22, 78, 80, 103, 123). Overexpression of a constitutively active FOXO1 in C2C12 muscle cells promotes expression of atrogin 1 (F-box protein 32) and muscle-specific RING finger protein 1, the 2 ubiquitin ligases involved in skeletal muscle atrophy (105). Expression of a dominant-negative FOXO1 construct in myotubes or in rodent muscle decreases atrogin-1 expression and muscle atrophy (105). Transgenic FOXO1 in skeletal muscle increases expression of cathepsin L, an atrophy-related lysosomal protease, which is associated with reduced skeletal muscle mass and body weight (55). Moreover, the genes encoding structural proteins of type I muscles (slow twitch, red muscle) are downregulated concomitant with a decreased size of both type I and type II fibers. The coordinate regulation of cathepsin L and type I muscle genes may account at least in part for the loss of muscle mass and glycemic control owing to hyperactivated FOXO (55).

Hence, physiological switch of FOXO1 activity, that is, on in fasting and off in feeding sate, is required for the nutrient/energy homeostasis in the skeletal muscle through carbohydrate/lipid switch. Severe starvation may trigger FOXO1-mediated autophagy and atrophy that break down protein for energy supply, the mechanism that underlies the loss of muscle mass and glycemic control under insulin resistance.

FOXO1 in Adipose Tissue

Adipose tissue contributes to metabolic regulation in several ways: (a) to combust fuel and generate heat to maintain body temperature (mainly in brown adipose tissue) (72); (b) to store excess energy in the form of triglycerides and mobilize the stored lipids for energy supply during energy deprivation (mainly in white adipose tissue) (66); and (c) as an endocrine organ to secrete adipokines and cytokines (e.g., leptin and adiponectin) that control energy homeostasis in adipocytes and inform the central nervous system of nutrient homeostasis (31). The prerequisites for these functions are differentiation and maintenance of adipocytes, in which FOXO1 plays a key role by interacting with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ), the transcription factor that promotes adipogenesis and fat storage (Fig. 5) (28, 88, 94, 115).

FIG. 5.

Regulation of adipocyte differentiation by FOXO1. Activation of FOXO1 facilitate its nuclear re-distribution and binding to PPARγ. The association of FOXO1 with PPARγ lead to 2 consequences: (a) it disrupts the PPARγ-RXRα complex, which is required for the binding of PPARγ to DNA (the PPRE) to elicit expression for genes that are responsible for adipocyte differentiation; (b) it transrepresses the PPARγ transactivation of target gene expression and inhibit adipocyte differentiation. The entry of active FOXO1 into nuclei also induces p21 (a cell cycle inhibitor) and blocks adipocyte differentiation. SirT2 and high-fat diet that hyperactivate FOXO1 can disrupt lipid storage and energy homeostasis in adipose tissue. HFD, high-fat diet; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ; PPRE, PPAR response element.

Adipogenesis, during which fibroblast-like preadipocytes differentiate into lipid-laden and insulin-responsive adipocytes, experiences several stages, including mesenchymal precursor, committed preadipocyte, growth-arrested preadipocyte, mitotic clonal expansion, terminal differentiation, and mature adipocyte (69). PPARγ exclusively regulates both the terminal differentiation and metabolism in mature adipocytes, by binding as a heterodimer with RXRα DNA at PPAR response elements (28). FOXO1 is a PPARγ-interacting protein that antagonizes PPARγ activity (6, 26, 28). This inhibition is achieved by disrupting the DNA binding activity of a PPARγ/RXRα heterodimeric complex (6, 26), and trans-repressing PPARγ transactivation via direct protein–protein interactions (Fig. 5) (28). FOXO1 represses transcription from either the PPARγ1or PPARγ2 promoter; however, this inhibition is attenuated by insulin treatment, suggesting that insulin-induced phosphorylation drives PPAR-γ activity by inhibiting FOXO1 (6). Mutation of insulin-induced phosphorylation sites in FOXO1 retains the repression of PPARγ1 promoter, and partly dampens the suppression of PPARγ2 promoter in either basal or insulin-stimulated cells (6).

Since acetyl-modification affects FOXO1 activity, the deacetylase SirT2 blocks adipocyte differentiation (50). SirT2-mediated deacetylation increases the association of FOXO1 with PPARγ, and knockdown of SirT2 restores PPARγ activity as observed with the use of constitutively acetylated FOXO1 (Fig. 5) (115). The trans-repression of FOXO1 is independent and dissectible from its trans-activation effect that is DBD dependent. The transrepression requires an evolutionally conserved 31 amino acid region containing the LXXLL-motif (28). Regardless, insulin prevents FOXO1–PPARγ interactions and diminishes the trans-repression of PPARγ genes by Akt-catalyzed phosphorylation and nuclear exclusion of FOXO1, enabling insulin signal to promote PPARγ-driven adipogenesis (28).

In line with the negative role for FOXO1 in adipocyte differentiation, FOXO1 might arrest the cell cycle that is required in the early stages of adipose conversion, via cell cycle inhibitor p21 (89). Constitutively active FOXO1 inhibits differentiation of the preadipocyte cell line 3T3-F442A cells, whereas haploinsufficiency of FOXO1 restores the size of white adipocytes in mice under a high-fat diet (89). Transgenic mice, which selectively overexpress the dominant-inhibitory FOXO1 in adipose tissue, exhibited improved glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity, and increased energy expenditure (88). Overexpression of dominant-negative FOXO1 in white adipose tissue (WAT) increases fat mass, number of small adipocytes, and upregulates adiponectin and Glut 4. Overexpression of the same mutant FOXO1 in brown adipose tissue (BAT) increases oxygen consumption and upregulates the Ppargc1 and uncoupling protein 1 that promote mitochondrial metabolism (88). In particular, the effects of overexpression of mutant FOXO1 on glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity under a high-fat diet are greater than under a normal diet (88). These findings support the paradigm of improving energy and nutrient homeostasis in adipose tissue through FOXO1 ablation that increases energy store in WAT and increases energy expenditure in BAT.

Therefore, FOXO1 can be an attractive target to improve the energy homeostasis in adipose tissue. Inhibition of FOXO1 activates PPARγ/RXRα but suppresses cell cycle inhibitor p21, which promotes adipocyte differentiation and maintenance. Targeting FOXO1 can eventually increase energy store in WAT and increases energy expenditure in BAT.

FOXO1 in Pancreatic β-Cells

Pancreatic β-cells respond to the elevation of circulating glucose and other nutrients, and secrete insulin that triggers the PI3K → Akt → FOXO1 signal cascade to adapt to changing metabolic demands and maintains nutrient homeostasis in both β-cells and peripheral tissues. During this process, β-cells metabolize glucose, increasing the [ATP]/[ADP] ratio to inhibit the K+-ATP channel and open the voltage-gated calcium channels that promote the secretion of insulin-containing granules (75). FOXO1 is the most predominantly expressed isoform in isolated mouse islets compared with FOXO3 and FOXO4 (62), and has been implicated in the regulation of proliferation (growth) and stress resistance of pancreatic β-cell (15, 33, 61).

The development and proliferation of β-cells require multiple transcription factors—pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1 (PDX1), neurogenin 3, and cytokeratin 19—that induce expression of insulin, islet amyloid polypeptide, and Glut2, but suppresses glucagon expression (1, 3). In the human fetal pancreas FOXO1 has been found to negatively regulate β-cell differentiation by suppressing PDX1, neurogenin 3, and NKX61 (3). Disruption of PDX1 in mice leads to the development of type II diabetes due to impaired expression of both Glut2 and insulin (1). PDX1 transcription is regulated positively by FOXA2 but negatively by FOXO1 (62, 68). Because these 2 forkhead transcription factors share common DNA-binding sites in the Pdx1 promoter, FOXO1 competes with FOXA2 for binding to Pdx1 promoter and inhibits PDX1 transcription (62). Moreover, nuclear translocation of FOXO1 is prone to exclude PDX1 from the nuclei, or vice versa (3, 57, 62). This serves as a second mechanism that FOXO1 inhibits β-cell proliferation (Fig. 6). As such, Irs2 knockout mice that show highly nuclear distribution of active FOXO1 suffer from β-cell failure (62). Functional β-cells expressing Irs2 repopulated the pancreas, restoring sufficient β-cell function to compensate for insulin resistance in the obese mice (73). Remarkably, the ablation of one allele of FOXO1 restores β-cell proliferation (62), and the beneficial effect of one-allele-of-FOXO1 deletion was also observed in PDX1 knockout mice (β-cell-specific knockout for PDX1) (39). On the other hand, transgenic mice that selectively overexpress Akt in β-cells increase β-cell survival and cell size (24). Recently, downregulation of Akt activity was implicated in dexamethasone and prostaglandin E2-induced pancreatic β-cell dysfunction, in which c-jun-N-terminal kinase 1 activation leads to nuclear accumulation of FOXO1 and nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling of PDX1 (57, 84, 122). This mechanism is implicated in fatty acid-induced β-cell apoptosis and endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced β-cell dysfunction (79). Inhibition of either c-jun-N-terminal kinase or FOXO1 protects pancreatic β-cells against dysfunction (57, 79, 84, 122).

FIG. 6.

The regulation of β-cell function by FOXO1. FOXO1 competes with FOXA2 for the PDX1 promoter and represses expression of PDX1 and probably NGN3 and NKX61, the factors responsible for β-cell proliferation. FOXO1 also excludes PDX1 protein from the nuclei in a reciprocal way. Thus, activation and nuclear redistribution of FOXO1 suppresses PDX1, NGN3, and NKX61, resulting in the inhibition of β-cell proliferation. This effect was enhanced during insulin resistance and ER stress or high FFA influx. In low nutrition, however, FOXO1 is activated due to the silence of PI3K-Akt or MAPK inhibitory pathways, which promotes β-cell proliferation through Cyclin D1. Moreover, FOXO1 plays an important role in protecting β-cell from oxidative stress, by forming complex with PML body and SirT1 to undergoes activation and induce antioxidant enzymes like MnSOD and catalase. FOXA2, forkhead box A2; JNK, c-jun-N-terminal kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MnSOD, manganese superoxide dismutase; NGN3, neurogenin 3; PDX1, pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1; PML, promyelocytic leukemia.

During stress conditions, however, nuclear translocation of FOXO1 protects β-cell against oxidative stress-induced failure (63) or promotes its proliferation in low nutrition (2) (Fig. 6). During hyperglycemia, glucose follows the enolization pathway to generate superoxide that induces oxidative insult because intracellular glucose is overloaded during glycolysis in the β-cell (98). In this case, FOXO1 enters the nuclei of β-cells and initiates NeuroD/MafA pathway to protect against pancreatic β-cell failure, by forming a complex with the promyelocytic leukemia protein and the NAD+-dependent deacetylase SirT1 (63). Most recently, the study of β-cells exposed to low nutrition reveals an additional beneficial role of FOXO1 activation: overexpression of FOXO1 promotes the proliferation of cultured pancreatic β-cells exposed to low nutrition, without obvious change in apoptosis compared with the control group (2). This study with specific inhibitors reveals that PI3 kinase and MAPS kinase signaling pathways are dampened, and that the induction of CyclinD1 expression by activated FOXO1 in low nutrition is responsible for the improved proliferation of β-cells (2).

Therefore, FOXO1 appears to play a dual role in regulating β-cell function: to increase stress resistance and to inhibit the proliferation of β-cells. This highlights the significance of a balanced FOXO1 activity in β-cell regulation under physiological conditions, and should be true in the regulation of other organs. Hyperactive or hypoactive FOXO1 could result in β-cell failure in either case.

Perspective and Conclusion

FOXO1 is a regulated transcription factor that is studied extensively in terms of its structure, activity regulation, and function in energy/nutrient homeostasis. Using genetically generated mouse models, FOXO1 has been shown to regulate general nutrient homeostasis; hepatic glucose production; insulin secretion in β-cells and β-cell growth; survival and function; and fat and muscle masses. Evidence from tissue-specific mouse models reveals an organ-dependent pattern of FOXO1 function, and suggests that FOXO1 could be a therapeutic target for metabolic diseases with insulin resistance, such as obesity, diabetes, and nonalcoholic fatty liver diseases.

However, a few outstanding questions remain to be addressed before therapeutic strategies can be developed for the metabolic diseases. First, at the molecular level, multiple posttranslational modifications, including phosphorylation, acetylation, methylation, glycosylation, and ubiquitinylation, modulate FOXO1 in response to nutrient or stress stimuli, which switch on or off FOXO1 activity. How these posttranslational modifications coordinate with each other to regulate FOXO1 activity remains elusive or controversial. Deacetylation of FOXO1 by SirT1 represses its transcriptional activity (13, 86, 120), but other evidence suggests that FOXO1 acetylation increases its phosphorylation and nuclear exclusion that promotes ubiquitination-mediated degradation (82a). Second, while FOXO1 appears to exert organ-dependent function in regulating metabolism, how FOXO1 achieves the cross talk between tissues is largely unsettled. For instance, knockout of insulin receptor in the pancreatic β-cell [β-cell-specific insulin receptor knockout (βIRKO) mice] conceivably activates FOXO1 and blunts PDK1 and insulin secretion, and the βIRKO mice did exhibit a selective loss of acute insulin release in response to glucose and a progressive impairment of glucose tolerance (64). However, β-cell and muscle insulin receptor double-knockout mice show an improvement rather than a deterioration of glucose tolerance when compared with βIRKO mice (83). Third, although ablation of FOXO1 appears to be beneficial to improve metabolism in many tissues, the physiological role of FOXO1 remains to be defined. For example, activation of FOXO (including FOXO1) has been shown to induce atrophy and heart dysfunction, and inhibition of transcription factors attenuates atrophy (99). Paradoxically, homozygous FOXO1 deletion is embryonic lethal as a consequence of incomplete vascular development (42). Moreover, FOXO1 does not necessarily act as a culprit of pathogenesis. Instead, FOXO1 can elicit signal cascade to increase stress tolerance in multiple organs (63, 113) or increase insulin sensitivity in adipose tissue (6, 7). In contrast to the observation of increased expression and activity of the transcription factor FOXO1 in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (111), constitutive active FOXO1 was suggested to suppress lipogenesis in transgenic mice (121) and normalize fatty acid synthase expression in phosphatase and tensin homolog null cells (40). Therefore, the differential physiological roles of FOXO1 in metabolism, development, and stress resistance must be well established and taken into consideration before targeting FOXO1 for clinic therapy of metabolic diseases.

Abbreviations Used

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- Atg1

atrogin 1 (F-box protein 32)

- βIRKO

β-cell-specific insulin receptor knockout

- BAT

brown adipose tissue

- CBP

CREB (cAMP response element-binding) binding protein

- CNTR

control

- Cpe

carboxypeptidase E

- DBD

DNA binding domain

- DIO

diet-induced obesity

- ETC

electron transport chain

- FA

fatty acid

- FAO

fatty acid oxidation

- FFA

free fatty acid

- FOXA2

forkhead box A2

- FOXO

forkhead box O

- G6P

glucose 6-phosphate

- HFD

high-fat diet

- Hmox1

heme oxygenase 1

- IκB

inhibitor of NF-kB

- IKK

IκB kinase

- Irs

insulin receptor substrates

- JNK

c-jun-N-terminal kinase

- LDKO

liver-specific Irs1 and Irs2 double knockout

- LPL

lipoprotein lipase

- LXRα

liver X receptor α

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MnSOD

manganese superoxide dismutase

- MST1

mammalian sterile 20-like kinase-1

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- MTP

microsomal triglyceride transfer protein

- MuRF1

muscle-specific RING finger protein 1

- NF-κB

nuclear factor κB

- NGN3

neurogenin 3

- O-GlcNAc

O-linked β-N-acetyl-glucosamine

- O-GlcNAcT

O-linked β-N-acetyl-glucosamine transferase

- PDH

pyruvate dehydrogenase

- PDK1

3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1

- PDK4

pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase-4

- PDX1

pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1

- PEPCK

phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase

- PI3K

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- PML

promyelocytic leukemia

- Pomc

pro-opiomelanocortin

- PPARγ

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ

- PPRE

PPAR response elements

- PRMT1

protein arginine methyltransferase 1

- RXRα

retinoid X receptor α

- Sgk

serum/glucocorticoid-inducible protein kinase

- SirT1 or 2

sirtuin 1 or 2

- SREBP-1c

sterol-regulatory-element-binding protein 1c

- TG

triglyceride

- TKO

triple knockout

- Trb3

Tribbles homolog 3

- TSC1/2

tuberous sclerosis complex 1 and 2

- VLDL

very-low-density lipoprotein

- WAT

white adipose tissue

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health grants DK38712 and DK55326 (M.F.W.), and American Diabetes Association Mentor–based Postdoctoral Fellowship 7-08-MN-63 (M.F.W. and Z.C.). We apologize to the colleagues whose work is not specifically referenced owing to space limitations.

References

- 1.Ahlgren U. Jonsson J. Jonsson L. Simu K. Edlund H. Beta-cell-specific inactivation of the mouse Ipf1/Pdx1 gene results in loss of the beta-cell phenotype and maturity onset diabetes. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1763–1768. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.12.1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ai J. Duan J. Lv X. Chen M. Yang Q. Sun H, et al. Overexpression of FoxO1 causes proliferation of cultured pancreatic beta cells exposed to low nutrition. Biochemistry. 2010;49:218–225. doi: 10.1021/bi901414g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Masri M. Krishnamurthy M. Li J. Fellows GF. Dong HH. Goodyer CG, et al. Effect of forkhead box O1 (FOXO1) on beta cell development in the human fetal pancreas. Diabetologia. 2010;53:699–711. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1632-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arden KC. FoxOs in tumor suppression and stem cell maintenance. Cell. 2007;128:235–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arden KC. FOXO animal models reveal a variety of diverse roles for FOXO transcription factors. Oncogene. 2008;27:2345–2350. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armoni M. Harel C. Karni S. Chen H. Bar-Yoseph F. Ver MR, et al. FOXO1 represses peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma1 and -gamma2 gene promoters in primary adipocytes. A novel paradigm to increase insulin sensitivity. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:19881–19891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600320200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armoni M. Kritz N. Harel C. Bar-Yoseph F. Chen H. Quon MJ, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma represses GLUT4 promoter activity in primary adipocytes, and rosiglitazone alleviates this effect. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:30614–30623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304654200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bastie CC. Nahle Z. McLoughlin T. Esser K. Zhang W. Unterman T, et al. FoxO1 stimulates fatty acid uptake and oxidation in muscle cells through CD36-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14222–14229. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413625200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belgardt BF. Husch A. Rother E. Ernst MB. Wunderlich FT. Hampel B, et al. PDK1 deficiency in POMC-expressing cells reveals FOXO1-dependent and -independent pathways in control of energy homeostasis and stress response. Cell Metab. 2008;7:291–301. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berry FB. Skarie JM. Mirzayans F. Fortin Y. Hudson TJ. Raymond V, et al. FOXC1 is required for cell viability and resistance to oxidative stress in the eye through the transcriptional regulation of FOXO1A. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:490–505. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brent MM. Anand R. Marmorstein R. Structural basis for DNA recognition by FoxO1 and its regulation by posttranslational modification. Structure. 2008;16:1407–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown MS. Goldstein JL. Selective versus total insulin resistance: a pathogenic paradox. Cell Metab. 2008;7:95–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brunet A. Sweeney LB. Sturgill JF. Chua KF. Greer PL. Lin Y, et al. Stress-dependent regulation of FOXO transcription factors by the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science. 2004;303:2011–2015. doi: 10.1126/science.1094637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bruning JC. Gautam D. Burks DJ. Gillette J. Schubert M. Orban PC, et al. Role of brain insulin receptor in control of body weight and reproduction. Science. 2000;289:2122–2125. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5487.2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buteau J. Accili D. Regulation of pancreatic beta-cell function by the forkhead protein FoxO1. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2007;9:140–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2007.00782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calnan DR. Brunet A. The FoxO code. Oncogene. 2008;27:2276–2288. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chakrabarti P. Kandror KV. FoxO1 controls insulin-dependent adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) expression and lipolysis in adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:13296–13300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800241200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng Z. Guo S. Copps K. Dong X. Kollipara R. Rodgers JT, et al. Foxo1 integrates insulin signaling with mitochondrial function in the liver. Nat Med. 2009;15:1307–1311. doi: 10.1038/nm.2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng Z. White MF. Foxo1 in hepatic lipid metabolism. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:219–220. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.2.10567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiba T. Kamei Y. Shimizu T. Shirasawa T. Katsumata A. Shiraishi L, et al. Overexpression of FOXO1 in skeletal muscle does not alter longevity in mice. Mech Ageing Dev. 2009;130:420–428. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Converso DP. Taille C. Carreras MC. Jaitovich A. Poderoso JJ. Boczkowski J. HO-1 is located in liver mitochondria and modulates mitochondrial heme content and metabolism. FASEB J. 2006;20:1236–1238. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4204fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crossland H. Constantin-Teodosiu D. Gardiner SM. Constantin D. Greenhaff PL. A potential role for Akt/FOXO signalling in both protein loss and the impairment of muscle carbohydrate oxidation during sepsis in rodent skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2008;586:5589–5600. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.160150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Lange P. Moreno M. Silvestri E. Lombardi A. Goglia F. Lanni A. Fuel economy in food-deprived skeletal muscle: signaling pathways and regulatory mechanisms. FASEB J. 2007;21:3431–3441. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8527rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dickson LM. Rhodes CJ. Pancreatic beta-cell growth and survival in the onset of type 2 diabetes: a role for protein kinase B in the Akt? Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;287:E192–E198. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00031.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dong XC. Copps KD. Guo S. Li Y. Kollipara R. DePinho RA, et al. Inactivation of hepatic Foxo1 by insulin signaling is required for adaptive nutrient homeostasis and endocrine growth regulation. Cell Metab. 2008;8:65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dowell P. Otto TC. Adi S. Lane MD. Convergence of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and Foxo1 signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45485–45491. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309069200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Essaghir A. Dif N. Marbehant CY. Coffer PJ. Demoulin JB. The transcription of FOXO genes is stimulated by FOXO3 and repressed by growth factors. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:10334–10342. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808848200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fan W. Imamura T. Sonoda N. Sears DD. Patsouris D. Kim JJ, et al. FOXO1 transrepresses peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma transactivation, coordinating an insulin-induced feed-forward response in adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:12188–12197. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808915200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Furuyama T. Kitayama K. Yamashita H. Mori N. Forkhead transcription factor FOXO1 (FKHR)-dependent induction of PDK4 gene expression in skeletal muscle during energy deprivation. Biochem J. 2003;375:365–371. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Furuyama T. Yamashita H. Kitayama K. Higami Y. Shimokawa I. Mori N. Effects of aging and caloric restriction on the gene expression of Foxo1, 3, and 4 (FKHR, FKHRL1, and AFX) in the rat skeletal muscles. Microsc Res Tech. 2002;59:331–334. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galic S. Oakhill JS. Steinberg GR. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;316:129–139. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glass DJ. Signalling pathways that mediate skeletal muscle hypertrophy and atrophy. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:87–90. doi: 10.1038/ncb0203-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glauser DA. Schlegel W. The emerging role of FOXO transcription factors in pancreatic beta cells. J Endocrinol. 2007;193:195–207. doi: 10.1677/JOE-06-0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greer EL. Oskoui PR. Banko MR. Maniar JM. Gygi MP. Gygi SP, et al. The energy sensor AMP-activated protein kinase directly regulates the mammalian FOXO3 transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:30107–30119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705325200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gross DN. van den Heuvel AP. Birnbaum MJ. The role of FoxO in the regulation of metabolism. Oncogene. 2008;27:2320–2336. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gross DN. Wan M. Birnbaum MJ. The role of FOXO in the regulation of metabolism. Curr Diab Rep. 2009;9:208–214. doi: 10.1007/s11892-009-0034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo S. Copps KD. Dong X. Park S. Cheng Z. Pocai A, et al. The Irs1 branch of the insulin signaling cascade plays a dominant role in hepatic nutrient homeostasis. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:5070–5083. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00138-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haeusler RA. Accili D. The double life of Irs. Cell Metab. 2008;8:7–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hashimoto N. Kido Y. Uchida T. Asahara S. Shigeyama Y. Matsuda T, et al. Ablation of PDK1 in pancreatic beta cells induces diabetes as a result of loss of beta cell mass. Nat Genet. 2006;8:589–593. doi: 10.1038/ng1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.He L. Hou X. Kanel G. Zeng N. Galicia V. Wang Y. Yang J. Wu H. Birnbaum MJ. Stiles BL. The critical role of AKT2 in hepatic steatosis induced by PTEN loss. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:2302–2308. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoekman MF. Jacobs FM. Smidt MP. Burbach JP. Spatial and temporal expression of FoxO transcription factors in the developing and adult murine brain. Gene Expr Patterns. 2006;6:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hosaka T. Biggs WH., III Tieu D. Boyer AD. Varki NM. Cavenee WK, et al. Disruption of forkhead transcription factor (FOXO) family members in mice reveals their functional diversification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2975–2980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400093101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Housley MP. Rodgers JT. Udeshi ND. Kelly TJ. Shabanowitz J. Hunt DF, et al. O-GlcNAc regulates FoxO activation in response to glucose. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:16283–16292. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802240200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Housley MP. Udeshi ND. Rodgers JT. Shabanowitz J. Puigserver P. Hunt DF, et al. A PGC-1alpha-O-GlcNAc transferase complex regulates FoxO transcription factor activity in response to glucose. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:5148–5157. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808890200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hribal ML. Nakae J. Kitamura T. Shutter JR. Accili D. Regulation of insulin-like growth factor-dependent myoblast differentiation by Foxo forkhead transcription factors. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:535–541. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hwang JH. Kim DW. Jo EJ. Kim YK. Jo YS. Park JH, et al. Pharmacological stimulation of NADH oxidation ameliorates obesity and related phenotypes in mice. Diabetes. 2009;58:965–974. doi: 10.2337/db08-1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ibdah JA. Perlegas P. Zhao Y. Angdisen J. Borgerink H. Shadoan MK, et al. Mice heterozygous for a defect in mitochondrial trifunctional protein develop hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1381–1390. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iskandar K. Cao Y. Hayashi Y. Nakata M. Takano E. Yada T, et al. PDK-1/FoxO1 pathway in POMC neurons regulates Pomc expression and food intake. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;298:E787–E798. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00512.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jacobs FM. Van Der Heide LP. Wijchers PJ. Burbach JP. Hoekman MF. Smidt MP. FoxO6, a novel member of the FoxO class of transcription factors with distinct shuttling dynamics. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:35959–35967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302804200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jing E. Gesta S. Kahn CR. SIRT2 regulates adipocyte differentiation through FoxO1 acetylation/deacetylation. Cell Metab. 2007;6:105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaestner KH. Knochel W. Martinez DE. Unified nomenclature for the winged helix/forkhead transcription factors. Genes Dev. 2000;14:142–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kamagate A. Dong HH. FoxO1 integrates insulin signaling to VLDL production. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:3162–3170. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.20.6882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kamagate A. Qu S. Perdomo G. Su D. Kim DH. Slusher S, et al. FoxO1 mediates insulin-dependent regulation of hepatic VLDL production in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2347–2364. doi: 10.1172/JCI32914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kamei Y. Miura S. Suganami T. Akaike F. Kanai S. Sugita S, et al. Regulation of SREBP1c gene expression in skeletal muscle: role of retinoid X receptor/liver X receptor and forkhead-O1 transcription factor. Endocrinology. 2008;149:2293–2305. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kamei Y. Miura S. Suzuki M. Kai Y. Mizukami J. Taniguchi T, et al. Skeletal muscle FOXO1 (FKHR) transgenic mice have less skeletal muscle mass, down-regulated Type I (slow twitch/red muscle) fiber genes, and impaired glycemic control. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41114–41123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400674200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kamei Y. Mizukami J. Miura S. Suzuki M. Takahashi N. Kawada T, et al. A forkhead transcription factor FKHR up-regulates lipoprotein lipase expression in skeletal muscle. Growth Regul. 2003;536:232–236. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kawamori D. Kaneto H. Nakatani Y. Matsuoka TA. Matsuhisa M. Hori M, et al. The forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 bridges the JNK pathway and the transcription factor PDX-1 through its intracellular translocation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1091–1098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508510200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim JJ. Li P. Huntley J. Chang JP. Arden KC. Olefsky JM. FoxO1 haploinsufficiency protects against high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance with enhanced peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activation in adipose tissue. Diabetes. 2009;58:1275–1282. doi: 10.2337/db08-1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim MS. Pak YK. Jang PG. Namkoong C. Choi YS. Won JC, et al. Role of hypothalamic Foxo1 in the regulation of food intake and energy homeostasis. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:901–906. doi: 10.1038/nn1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kitamura T. Feng Y. Kitamura YI. Chua SC., Jr. Xu AW. Barsh GS, et al. Forkhead protein FoxO1 mediates Agrp-dependent effects of leptin on food intake. Nat Med. 2006;12:534–540. doi: 10.1038/nm1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kitamura T. Ido KY. Role of FoxO proteins in pancreatic beta cells. Endocr J. 2007;54:507–515. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.kr-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kitamura T. Nakae J. Kitamura Y. Kido Y. Biggs WH., III Wright CV, et al. The forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 links insulin signaling to Pdx1 regulation of pancreatic beta cell growth. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1839–1847. doi: 10.1172/JCI200216857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kitamura YI. Kitamura T. Kruse JP. Raum JC. Stein R. Gu W, et al. FoxO1 protects against pancreatic beta cell failure through NeuroD and MafA induction. Cell Metab. 2005;2:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kulkarni RN. Bruning JC. Winnay JN. Postic C. Magnuson MA. Kahn CR. Tissue-specific knockout of the insulin receptor in pancreatic beta cells creates an insulin secretory defect similar to that in type 2 diabetes. Cell. 1999;96:329–339. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80546-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kulkarni RN. Laplante M. Sabatini DM. mTORC1 activates SREBP-1c and uncouples lipogenesis from gluconeogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:3281–3282. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000323107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Large V. Peroni O. Letexier D. Ray H. Beylot M. Metabolism of lipids in human white adipocyte. Diabetes Metab. 2004;30:294–309. doi: 10.1016/s1262-3636(07)70121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Leavens KF. Easton RM. Shulman GI. Previs SF. Birnbaum MJ. Akt2 is required for hepatic lipid accumulation in models of insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2009;10:405–418. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee CS. Sund NJ. Vatamaniuk MZ. Matschinsky FM. Stoffers DA. Kaestner KH. Foxa2 controls Pdx1 gene expression in pancreatic beta-cells in vivo. Diabetes. 2002;51:2546–2551. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.8.2546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lefterova MI. Lazar MA. New developments in adipogenesis. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009;20:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lehtinen MK. Yuan Z. Boag PR. Yang Y. Villen J. Becker EB, et al. A conserved MST-FOXO signaling pathway mediates oxidative-stress responses and extends life span. Cell. 2006;125:987–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li S. Brown MS. Goldstein JL. Bifurcation of insulin signaling pathway in rat liver: mTORC1 required for stimulation of lipogenesis, but not inhibition of gluconeogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:3441–3446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914798107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lidell ME. Enerback S. Brown adipose tissue-a new role in humans? Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2010;6:319–325. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2010.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lin X. Taguchi A. Park S. Kushner JA. Li F. Li Y, et al. Dysregulation of insulin receptor substrate 2 in beta cells and brain causes obesity and diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:908–916. doi: 10.1172/JCI22217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu Y. Dentin R. Chen D. Hedrick S. Ravnskjaer K. Schenk S, et al. A fasting inducible switch modulates gluconeogenesis via activator/coactivator exchange. Nature. 2008;456:269–273. doi: 10.1038/nature07349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Maechler P. Wollheim CB. Mitochondrial function in normal and diabetic beta-cells. Nature. 2001;414:807–812. doi: 10.1038/414807a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maiese K. Chong ZZ. Shang YC. OutFOXOing disease and disability: the therapeutic potential of targeting FoxO proteins. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Maiese K. Chong ZZ. Shang YC. Hou J. Clever cancer strategies with FoxO transcription factors. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:3829–3839. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.24.7231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mammucari C. Milan G. Romanello V. Masiero E. Rudolf R. Del PP, et al. FoxO3 controls autophagy in skeletal muscle in vivo. Cell Metab. 2007;6:458–471. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Martinez SC. Tanabe K. Cras-Meneur C. Abumrad NA. Bernal-Mizrachi E. Permutt MA. Inhibition of Foxo1 protects pancreatic islet beta-cells against fatty acid and endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. Diabetes. 2008;57:846–859. doi: 10.2337/db07-0595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Masiero E. Agatea L. Mammucari C. Blaauw B. Loro E. Komatsu M, et al. Autophagy is required to maintain muscle mass. Cell Metab. 2009;10:507–515. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Matsumoto M. Han S. Kitamura T. Accili D. Dual role of transcription factor FoxO1 in controlling hepatic insulin sensitivity and lipid metabolism. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2464–2472. doi: 10.1172/JCI27047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Matsumoto M. Pocai A. Rossetti L. DePinho RA. Accili D. Impaired regulation of hepatic glucose production in mice lacking the forkhead transcription factor foxo1 in liver. Cell Metab. 2007;6:208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82a.Matsuzaki H. Daitoku H. Hatta M. Aoyama H. Yoshimochi K. Fukamizu A. Acetylation of Foxo1 alters its DNA-binding ability and sensitivity to phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11278–11283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502738102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mauvais-Jarvis F. Virkamaki A. Michael MD. Winnay JN. Zisman A. Kulkarni RN, et al. A model to explore the interaction between muscle insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction in the development of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2000;49:2126–2134. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.12.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Meng Z. Lv J. Luo Y. Lin Y. Zhu Y. Nie J, et al. Forkhead box O1/pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1 intracellular translocation is regulated by c-Jun N-terminal kinase and involved in prostaglandin E2-induced pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction. Endocrinology. 2009;150:5284–5293. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Michael MD. Kulkarni RN. Postic C. Previs SF. Shulman GI. Magnuson MA, et al. Loss of insulin signaling in hepatocytes leads to severe insulin resistance and progressive hepatic dysfunction. Mol Cell. 2000;6:87–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Motta MC. Divecha N. Lemieux M. Kamel C. Chen D. Gu W, et al. Mammalian SIRT1 represses forkhead transcription factors. Cell. 2004;116:551–563. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Naimi M. Gautier N. Chaussade C. Valverde AM. Accili D. Van OE. Nuclear forkhead box O1 controls and integrates key signaling pathways in hepatocytes. Endocrinology. 2007;148:2424–2434. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nakae J. Cao Y. Oki M. Orba Y. Sawa H. Kiyonari H, et al. Forkhead transcription factor FoxO1 in adipose tissue regulates energy storage and expenditure. Diabetes. 2008;57:563–576. doi: 10.2337/db07-0698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nakae J. Kitamura T. Kitamura Y. Biggs WH., III Arden KC. Accili D. The forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 regulates adipocyte differentiation. Dev Cell. 2003;4:119–129. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00401-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nakae J. Oki M. Cao Y. The FoxO transcription factors and metabolic regulation. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:54–67. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nowak K. Killmer K. Gessner C. Lutz W. E2F-1 regulates expression of FOXO1 and FOXO3a. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1769:244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Obsil T. Obsilova V. Structure/function relationships underlying regulation of FOXO transcription factors. Oncogene. 2008;27:2263–2275. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Paik JH. Kollipara R. Chu G. Ji H. Xiao Y. Ding Z. Miao L. Tothova Z. Horner JW. Carrasco DR. Jiang S. Gilliland DG. Chin L. Wong WH. Castrillon DH. DePinho RA. FoxOs are lineage-restricted redundant tumor suppressors and regulate endothelial cell homeostasis. Cell. 2007;128:309–323. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pang WJ. Yu TY. Bai L. Yang YJ. Yang GS. Tissue expression of porcine FoxO1 and its negative regulation during primary preadipocyte differentiation. Mol Biol Rep. 2009;36:165–176. doi: 10.1007/s11033-007-9163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Plum L. Lin HV. Dutia R. Tanaka J. Aizawa KS. Matsumoto M, et al. The obesity susceptibility gene Cpe links FoxO1 signaling in hypothalamic pro-opiomelanocortin neurons with regulation of food intake. Nat Med. 2009;15:1195–1201. doi: 10.1038/nm.2026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Postic C. Dentin R. Girard J. Role of the liver in the control of carbohydrate and lipid homeostasis. Diabetes Metab. 2004;30:398–408. doi: 10.1016/s1262-3636(07)70133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Puig O. Tjian R. Transcriptional feedback control of insulin receptor by dFOXO/FOXO1. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2435–2446. doi: 10.1101/gad.1340505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Robertson RP. Harmon J. Tran PO. Tanaka Y. Takahashi H. Glucose toxicity in beta-cells: type 2 diabetes, good radicals gone bad, and the glutathione connection. Diabetes. 2003;52:581–587. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.3.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ronnebaum SM. Atterson C. The FoxO family in cardiac function and dysfunction. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72:81–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Roskoski R, editor. Biochemistry. New York: Elsevier Health Sciences; 1996. pp. 169–171. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Samuel VT. Choi CS. Phillips TG. Romanelli AJ. Geisler JG. Bhanot S, et al. Targeting foxo1 in mice using antisense oligonucleotide improves hepatic and peripheral insulin action. Diabetes. 2006;55:2042–2050. doi: 10.2337/db05-0705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sandri M. Signaling in muscle atrophy and hypertrophy. Physiology (Bethesda) 2008;23:160–170. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00041.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sandri M. Sandri C. Gilbert A. Skurk C. Calabria E. Picard A, et al. Foxo transcription factors induce the atrophy-related ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1 and cause skeletal muscle atrophy. Cell. 2004;117:399–412. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00400-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Schuff M. Siegel D. Bardine N. Oswald F. Donow C. Knochel W. FoxO genes are dispensable during gastrulation but required for late embryogenesis in Xenopus laevis. Dev Biol. 2010;337:259–273. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Stitt TN. Drujan D. Clarke BA. Panaro F. Timofeyva Y. Kline WO, et al. The IGF-1/PI3K/Akt pathway prevents expression of muscle atrophy-induced ubiquitin ligases by inhibiting FOXO transcription factors. Mol Cell. 2004;14:395–403. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00211-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Taguchi A. Wartschow LM. White MF. Brain IRS2 signaling coordinates life span and nutrient homeostasis. Science. 2007;317:369–372. doi: 10.1126/science.1142179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Taniguchi CM. Kondo T. Sajan M. Luo J. Bronson R. Asano T, et al. Divergent regulation of hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism by phosphoinositide 3-kinase via Akt and PKClambda/zeta. Cell Metab. 2006;3:343–353. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tothova Z. Kollipara R. Huntly BJ. Lee BH. Castrillon DH. Cullen DE. McDowell EP. Lazo-Kallanian S. Williams IR. Sears C. Armstrong SA. Passegué E. DePinho RA. Gilliland DG. FoxOs are critical mediators of hematopoietic stem cell resistance to physiologic oxidative stress. Cell. 2007;128:325–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tsai KL. Huang CY. Chang CH. Sun YJ. Chuang WJ. Hsiao CD. Crystal structure of the human FOXK1a-DNA complex and its implications on the diverse binding specificity of winged helix/forkhead proteins. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17400–17409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600478200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]