Abstract

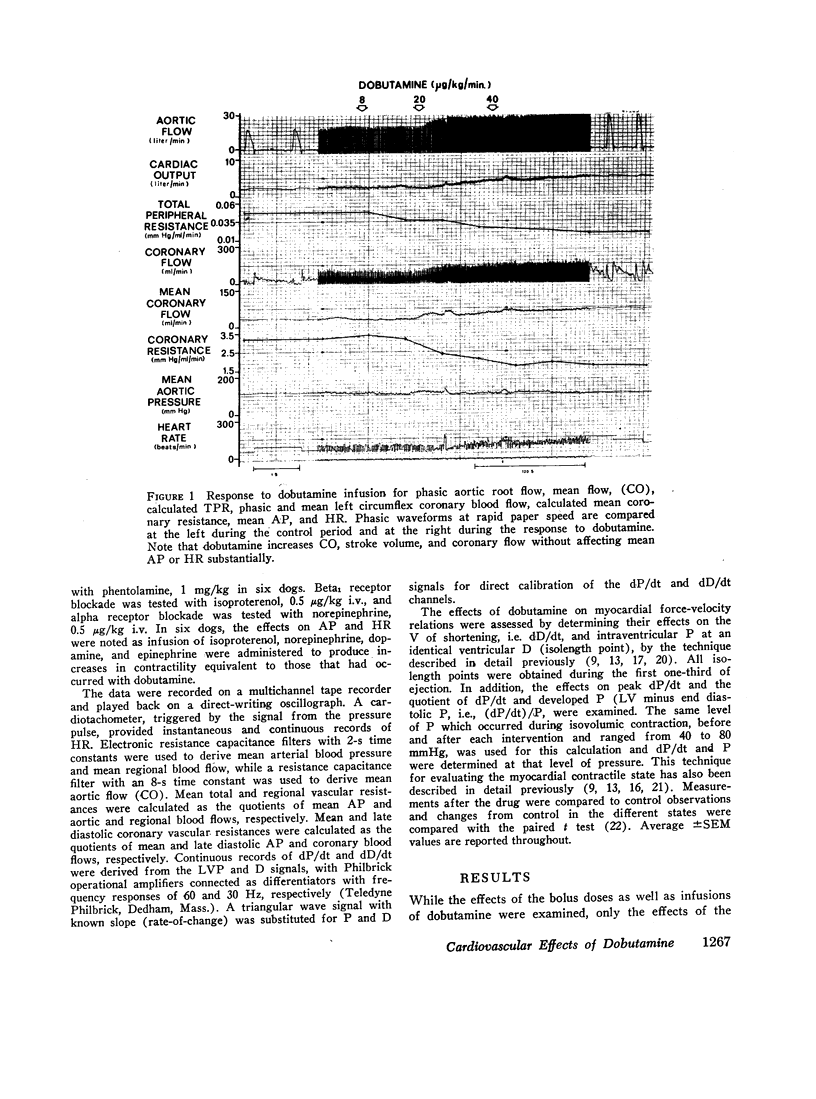

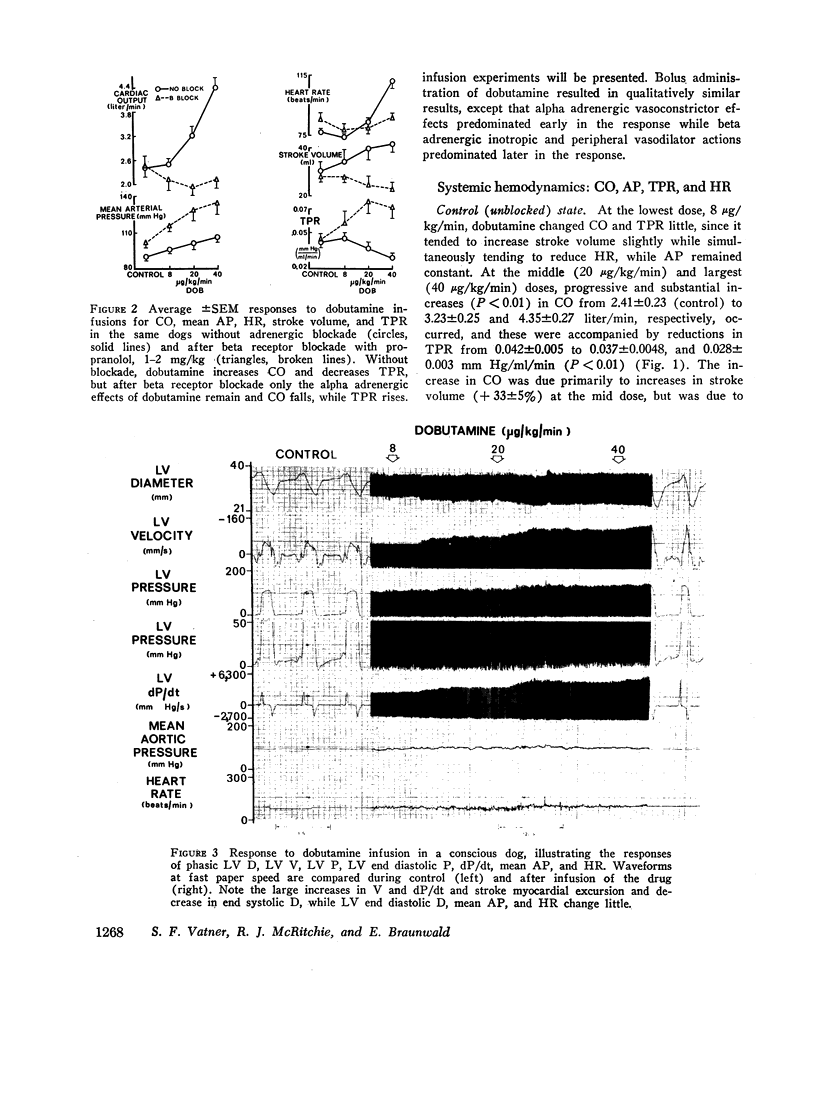

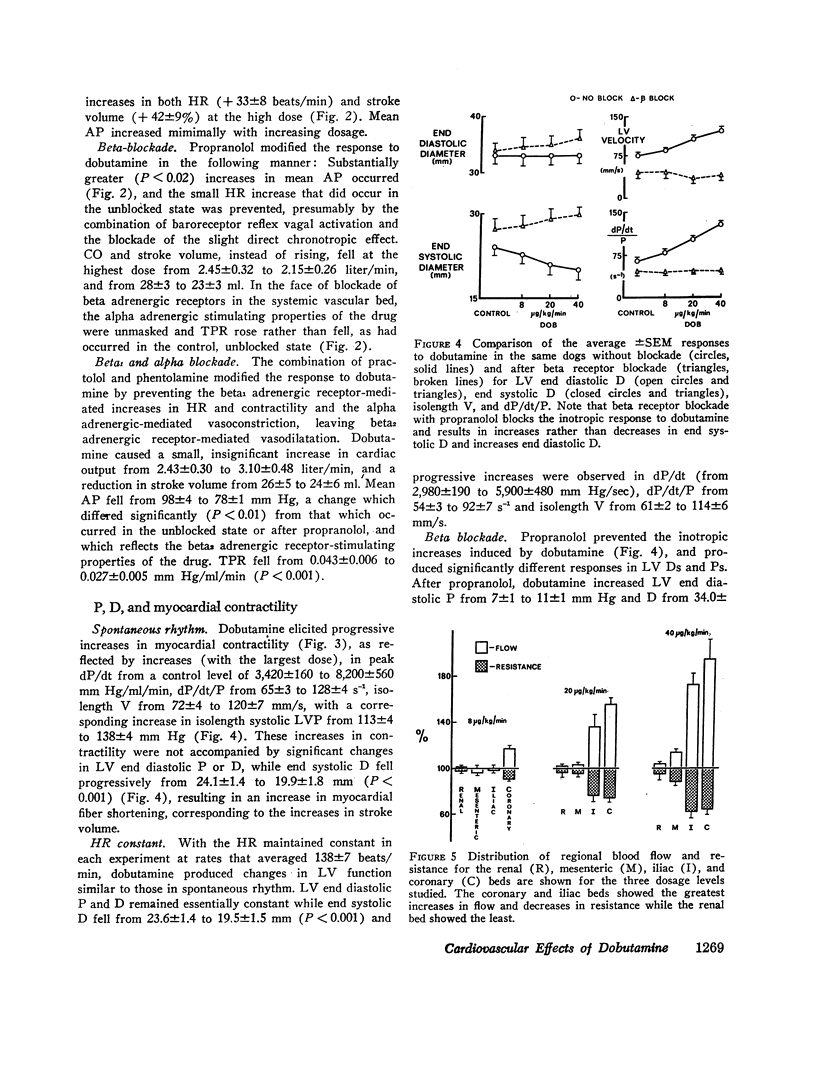

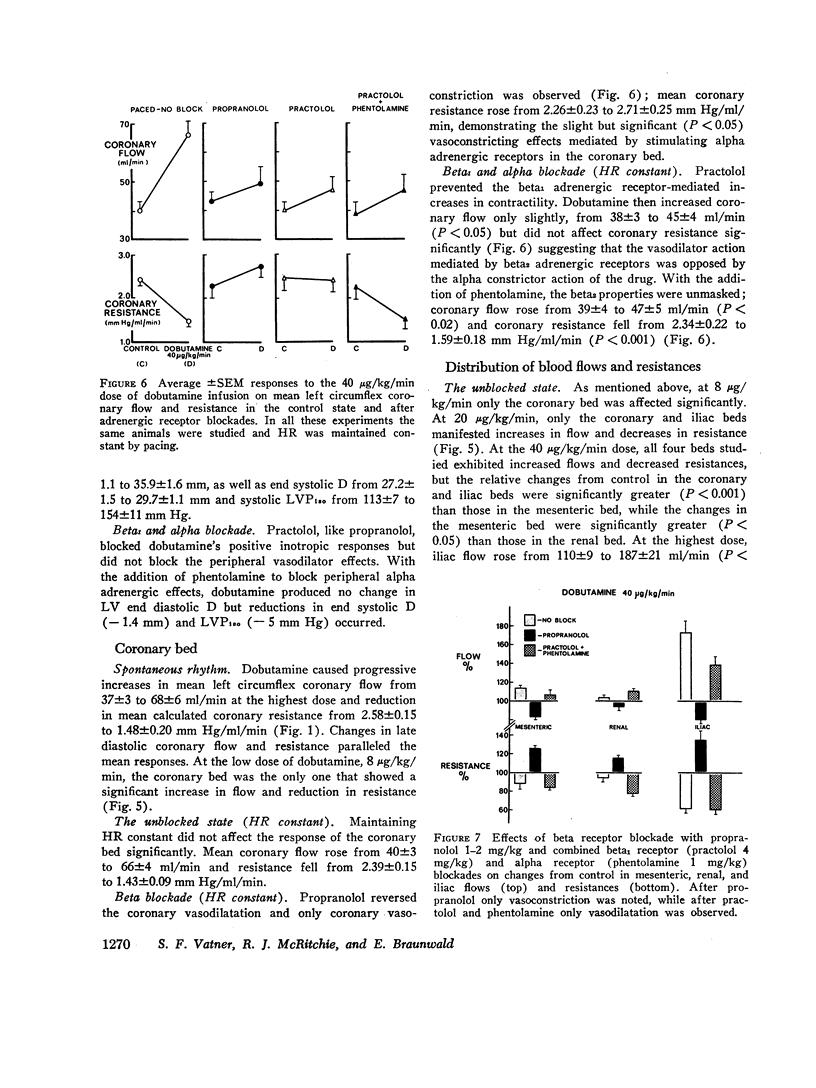

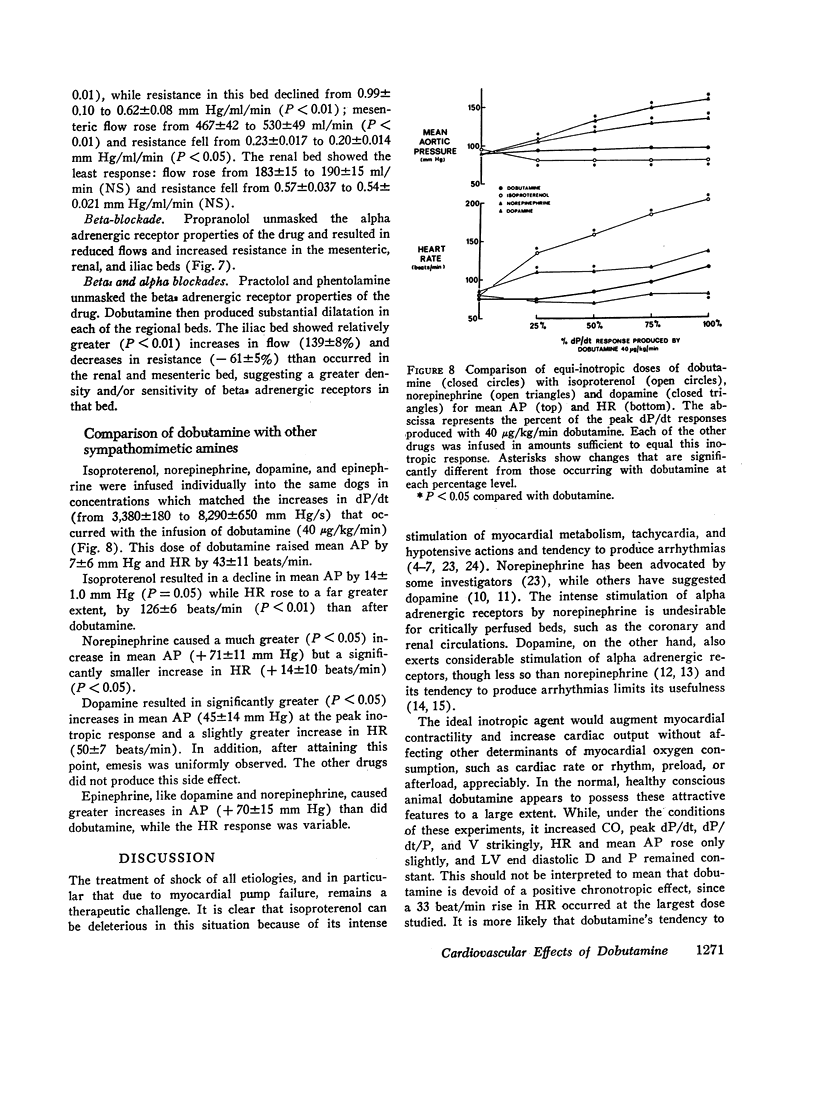

The effects of dobutamine ([±]-4-[2-[[3-(p-hydroxyphenyl)-1-methyl propyl] amino] ethyl] pyrocatechol hydrochloride), a new synthetic cardioactive sympathomimetic amine, were examined on direct and continuous measurements of left ventricular (LV) diameter (D), pressures (P), velocity of shortening (V), dP/dt, dP/dt/P, arterial pressure, cardiac output, and regional blood flows in the left circumflex coronary, mesenteric, renal, and iliac beds in healthy, conscious dogs. At the highest dose of dobutamine examined, 40 μg/kg/min, the drug increased dP/dt/P from 65±3 to 128±4 s-1 and isolength velocity from 72±4 to 120±7 mm/s without affecting LV end diastolic D significantly. Mean arterial P rose from 92±2 to 104±3 mm Hg and heart rate from 78±3 to 111±7 beats/min, while LV end systolic D fell from 24.1±1.4 to 19.9±1.8 mm, reflecting a rise in stroke volume from 30±4 to 42±3 ml. Cardiac output rose from 2.41±0.23 to 4.35±0.28 liter/min, while calculated total peripheral resistance declined from 0.042±0.005 to 0.028±0.003 mm Hg/ml/min. The greatest increases in flow and decreases in calculated resistance occurred in the iliac and coronary beds, and the least occurred in the renal bed. Propranolol blocked the inotropic and beta2 dilator responses while vasoconstricting effects mediated by alpha adrenergic stimulation remained in each of the beds studied. When dobutamine was infused after a combination of practolol and phentolamine, dilatation occurred in each of the beds studied. These observations indicate that dobutamine is a potent positive inotropic agent with relatively slight effects on preload, afterload, or heart rate, and thus may be a potentially useful clinical agent. The one property of this drug which is not ideal is its tendency to cause a redistribution of cardiac output favoring the muscular beds at the expense of the kidney and visceral beds.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Franklin D. E., Watson N. W., Pierson K. E., Van Citters R. L. Technique for radio telemetry of blood-flow velocity from unrestrained animals. Am J Med Electron. 1966;5(1):24–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GLICK G., SONNENBLICK E. H., BRAUNWALD E. MYOCARDIAL FORCE-VELOCITY RELATIONS STUDIED IN INTACT UNANESTHETIZED MAN. J Clin Invest. 1965 Jun;44:978–988. doi: 10.1172/JCI105215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg L. I. Cardiovascular and renal actions of dopamine: potential clinical applications. Pharmacol Rev. 1972 Mar;24(1):1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg L. I. The treatment of cardiogenic shock. VI. The search for an ideal drug. Am Heart J. 1968 Mar;75(3):416–420. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(68)90098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar R. M., Loeb H. S., Pietras R. J., Tobin J. R., Jr Ineffectiveness of isoproterenol in shock due to acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 1967 Dec 25;202(13):1124–1128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar R. M., Loeb H. S. Use of drugs in cardiogenic shock due to acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1972 May;45(5):1111–1124. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.45.5.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins C. B., Millard R. W., Braunwald E., Vatner S. F. Effects and mechanisms of action of dopamine on regional hemodynamics in the conscious dog. Am J Physiol. 1973 Aug;225(2):432–437. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1973.225.2.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn L. A., Kline H. J., Goodman P., Johnson C. D., Marano A. J. Effects of isoproterenol on hemodynamic alterations, myocardial metabolism, and coronary flow in experimental acute myocardial infarction with shock. Am Heart J. 1969 Jun;77(6):772–783. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(69)90411-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipp H., Falicov R. E., Resnekov L., King S. The effects of dopamine on depressed myocardial function following coronary embolization in the closed-chest dog. Am Heart J. 1972 Aug;84(2):208–214. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(72)90335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb H. S., Winslow E. B., Rahimtoola S. H., Rosen K. M., Gunnar R. M. Acute hemodynamic effects of dopamine in patients with shock. Circulation. 1971 Aug;44(2):163–173. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.44.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroko P. R., Kjekshus J. K., Sobel B. E., Watanabe T., Covell J. W., Ross J., Jr, Braunwald E. Factors influencing infarct size following experimental coronary artery occlusions. Circulation. 1971 Jan;43(1):67–82. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.43.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroko P. R., Libby P., Braunwald E. Effect of pharmacologic agents on the function of the ischemic heart. Am J Cardiol. 1973 Dec;32(7):930–936. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(73)80160-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason D. T., Braunwald E., Covell J. W., Sonnenblick E. H., Ross J., Jr Assessment of cardiac contractility. The relation between the rate of pressure rise and ventricular pressure during isovolumic systole. Circulation. 1971 Jul;44(1):47–58. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.44.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra S. N., Kezdi P. Hemodynamic effects of adrenergic stimulating and blocking agents in cardiogenic shock and low output state after myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1973 Jun;31(6):724–735. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(73)90007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller H., Ayres S. M., Gregory J. J., Giannelli S., Jr, Grace W. J. Hemodynamics, coronary blood flow, and myocardial metabolism in coronary shock; response of 1-norepinephrine and isoproterenol. J Clin Invest. 1970 Oct;49(10):1885–1902. doi: 10.1172/JCI106408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith H. J., Oriol A., Morch J., McGregor M. Hemodynamic studies in cardiogenic shock. Treatment with isoproterenol and metaraminol. Circulation. 1967 Jun;35(6):1084–1091. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.35.6.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley R. C., Goldberg L. I., Johnson C. E., McNay J. L. A hemodynamic comparison of dopamine and isoproterenol in patients in shock. Circulation. 1969 Mar;39(3):361–378. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.39.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vatner S. F., Franklin D., VanCitters R. L. Simultaneous comparison and calibration of the Doppler and electromagnetic flowmeters. J Appl Physiol. 1970 Dec;29(6):907–910. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1970.29.6.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vatner S. F., Higgins C. B., Patrick T., Franklin D., Braunwald E. Effects of cardiac depression and of anesthesia on the myocardial action of a cardiac glycoside. J Clin Invest. 1971 Dec;50(12):2585–2595. doi: 10.1172/JCI106759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vatner S. F., Millard R. W., Higgins C. B. Coronary and myocardial effects of dopamine in the conscious dog: parasympatholytic augmentation of pressor and inotropic actions. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1973 Nov;187(2):280–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]