Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the UK with around 30 000 deaths per annum. There are an estimated 3 million people with the disease (900 000 diagnosed and 2.1 million undiagnosed), and COPD is estimated to be the third highest cause of mortality worldwide by the year 2020.1

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) 2010 guidelines for the management of COPD in primary and secondary care1 are a partial update of the original guidelines published in 2004.2 The new recommendations are principally concerned with spirometry, assessment of disease severity, and management of stable disease.

DIAGNOSIS OF COPD

A diagnosis of COPD is dependent on the presence of characteristic symptoms of cough and breathlessness, examination (principally to rule out other causes of cough/breathlessnes, such as cardiac disease, other lung disease), and the demonstration of airflow obstruction on spirometry.

The 2004 guidelines were unclear whether pre- or post-bronchodilator readings of forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) should be used to diagnose COPD. The new guidelines recommend that postbronchodilator readings should be used, which corresponds with requirements of the current UK Quality and Outcomes Framework.3

There has been debate surrounding the merits of using a fixed cut-off point of 0.7 of FEV1/FVC ratio for diagnosing COPD or using the lower limit of normal (LLN) where the bottom 5% of the healthy population is abnormal. The reason for this is that the fixed ratio tends to over diagnose airflow obstruction in older people and under diagnose airflow obstruction in younger people. In spite of increasing recognition of these limitations, there is conflicting evidence looking at the superiority of LLN or the fixed cut-off point in predicting a diagnosis of COPD. There is also a paucity of up do date post-bronchodilator reference values for the LLN. For these reasons the NICE 2010 guidelines continue to recommend the use of the fixed ratio. Further discussion of this issue can be found in a paper by Levy et al.4

The severity of airway obstruction is determined by predicted FEV1%. The 2004 NICE guidelines were out of phase with international definitions of severity and have been amended, as shown in Table 1. The international Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease guidelines5 are shown for comparison.

Table 1.

Degree of airflow obstruction severity according to National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE)1 and Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines.5

| NICE 20042 | GOLD 20095 | NICE 20101 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC | FEV1% predicted | Severity of airflow obstruction | ||

| Post-bronchodilator | Post-bronchodilator | |||

| <0.7 | ≥80% | Stage 1 mild | Stage 1 milda | |

| <0.7 | 50–79% | Mild | Stage 2 moderate | Moderate |

| <0.7 | 30–49% | Moderate | Stage 3 severe | Severe |

| <0.7 | <30% | Severe Stage | 4 very severe | Very severeb |

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease should not be diagnosed in the absence of symptoms in patients with mild airways obstruction.

FEV1 <50% in the presence of respiratory failure.

FVC = forced vital capacity. FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

Two points should be emphasised: first, the table reflects the severity of airflow obstruction not the severity of disease. Second, patients who have an FEV1% predicted ≥80% and FEV1/FVC ratio of <0.7 would formerly not have been considered as having COPD under the 2004 NICE guidance. Such patients would now be deemed as having airflow obstruction. This could have the consequence of greatly increasing the number of patients diagnosed with having COPD. However the 2010 guidelines state that symptoms should be present if COPD is to be diagnosed in this group of patients (that is, it is not sufficient to make a diagnosis of COPD if mild airflow obstruction alone is picked up on routine screening).

There may also be some anxiety in those patients that have their airflow severity upgraded by this guidance; for example, severity rating increased from moderate to severe. These patients may need reassurance that their lung function, disease severity, and prognosis remain unchanged.

ASSESSMENT OF DISEASE SEVERITY

Traditionally, disease severity has been equated with the degree of airflow obstruction. However, in recent years there has been an increasing recognition that COPD is not just a disease of the lungs, but has systemic manifestations; for example depression, muscle wasting, and general fatigue. In recognition of this, the 2010 NICE guidelines emphasise that an assessment of disease severity should be based not just on the degree of airflow obstruction, but also on a multi-dimensional assessment based on other factors, such as functional limitation and exacerbation frequency.

The recognition that assessment of COPD disease severity requires a multi-dimensional approach, has led to development of multi-dimensional indices. The BODE index6 assesses disease severity by measuring Body mass index, degree of airflow Obstruction (FEV1% predicted), Dyspnoea (Medical Research Council Dyspnoea Scale), and Exercise limitation (as measured by the 6-minute walking test).

The NICE guidelines conclude that this multi-dimensional assessment tool is a better predictor of mortality and exacerbation rate than FEV1 alone. Unfortunately, the 6-minute walking test is not very practical to carry out in primary care and so more primary-care friendly indices are being developed to look at the impact of the disease on the patient. The DOSE Index (Dyspnea, airflow Obstruction, Smoking status, and Exacerbation frequency)7 and COPD Assessment Tool8 may become more widely used in primary care in the near-future, although have not been formally assessed by NICE.

MANAGEMENT OF STABLE DISEASE

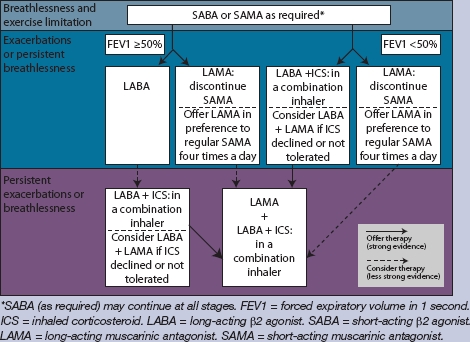

In recent years there have been several large scale studies looking at the effect of inhaled pharmacotherapy on current control of COPD in terms of the impact on patients' symptoms and quality of life, but also the effect of reducing future risk of exacerbations, mortality, and disease progression. These studies have led to changes in the recommendations concerning the place of various inhaled drugs. These are summarised in the treatment algorithm shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence 2010 guidelines: algorithm for inhaled pharmacotherapy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.1

The guidelines recommend classes of drug to be used, but not the specific drug. This is determined by cost, choice of device, side effects, and patient preference. One of the implications of the new guidance is that treatment of persistently symptomatic COPD with regular four-times daily ipratropium is no longer recommended; once-daily tiotropium is more cost-effective. Another implication is that inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)/long-acting β2 agonist (LABA) combinations are being recommended for use at an early stage in patients with severe disease (FEV1<50%) not just in patients with exacerbations. The unlicensed use of inhaled corticosteroids alone (that is, not in combination with LABA) is not recommended.

In spite of the apparent highlighting of pharmacotherapy in the update, overall the guidelines emphasise the importance of non-pharmacological management. In particular, smoking cessation remains a key priority in preventing the onset of disease and halting disease progression. In addition, pulmonary rehabilitation has been shown to provide benefit not only in patients with stable disease (improving health status, reducing hospital in-patient days), but also in reducing the risk of hospital readmission in patients recently discharged from hospital with an acute exacerbation of COPD. Further guidance on management can be found at the Primary Care Respiratory Society UK website (http://www.pcrs-uk.org).

The measurement of airflow obstruction is still important in diagnosing, assessing severity, and guiding treatment in COPD, but the 2010 NICE COPD guidelines emphasise that COPD is a multi-system disease, requiring a holistic approach to management; an approach ideally suited to primary care.

Provenance

Commissioned, not externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care (partial update) London: National Clinical Guideline Centre; 2010. http://www.nice.org.uk/CG101 (accessed 23 Dec 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. National clinical guideline on management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. Thorax. 2004;59(Suppl 1):1–232. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NHS Employers. Quality and Outcomes Framework guidance for GMS contract 2009/10: Delivering investment in general practice. London: NHS Employers; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy ML, Quanjer PH, Booker R, et al. Diagnostic spirometry in primary care: proposed standards for general practice compliant with American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society recommendations. Prim Care Respir J. 2009;18(3):130–147. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2009.00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: updated 2009. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. http://www.goldcopd.com/ (accessed 23 Dec 2010)

- 6.Celli BR, Cote CG, Marin JM, et al. The body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. NEJM. 2004;350:1005–1012. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones RC, Donaldson GC, Chavannes NH, et al. Derivation and validation of a composite index of severity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the DOSE Index. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(12):1189–1195. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200902-0271OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones PW, Harding G, Berry P, et al. Development and first validation of the COPD Assessment Test. Eur Respir J. 2009;34(3):648–654. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00102509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]