Abstract

Background

Since 2006 the Quality Outcomes Framework (QOF) has rewarded GPs for carrying out standardised assessments of the severity of symptoms of depression in newly diagnosed patients.

Aim

To gain understanding of GPs' opinions and perceived impact on practice of the routine introduction of standardised questionnaire measures of severity of depression through the UK general practice contract QOF.

Design of study

Semi-structured qualitative interview study, with purposive sampling and constant comparative analysis.

Setting

Thirty-four GPs from among 38 study general practices in three sites in England, UK: Southampton, Liverpool, and Norfolk.

Method

GPs were interviewed at a time convenient to them by trained interviewers. Interviews were audiorecorded and transcribed verbatim in preparation for thematic analysis, to identify key views.

Results

Analysis of the interviews suggested that the use of severity questionnaires posed an intrusion into the consultation. GPs discursively polarised two technologies: formal assessment versus personal enquiry, emphasising the need to ensure the scores are used sensitively and as an aid to clinical judgement rather than as a substitute. Importantly, these challenges implicitly served a function of preserving GPs' identities as professionals with expertise, constructed as integral to the process of diagnosis.

Conclusion

GP accounts indicated concern about threats to patient care. Contention between using severity questionnaires and delivering individualised patient care is significantly motivated by GP concerns to preserve professional expertise and identity. It is important to learn from GP concerns to help establish how best to optimise the use of severity questionnaires in depression.

Keywords: depression, diagnosis, general practice

INTRODUCTION

In April 2004, the UK government incorporated a pay-for-performance scheme in the GP contract, through the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF). Since April 2006 the contract has rewarded GPs for carrying out assessments of the severity of symptoms of depression at the outset of treatment in patients with a new diagnosis.1 The rationale is that national guidelines on depression recommend more active intervention for patients with moderate to severe depression (antidepressant treatment or referral for psychological treatment) than for mild depression (guided self-help and watchful waiting),2 and therefore accurate assessment of severity is necessary to decide on appropriate responses to new cases.

The QOF has not been received without controversy. Some have suggested it is in danger of encouraging a ‘medicine by numbers’ approach to practice, it poses a threat to professional status,3 and practitioners may perceive a deskilling effect.4 In particular, the use of questionnaire measures in depression is controversial and there have been calls for them to be removed from the QOF.5 Some practitioners have voiced concern that use of the severity questionnaires may diminish patient–doctor rapport and holism.4 GPs are apparently wary of using questionnaire scores to determine severity and decide on treatment. A recent quantitative analysis of treatment decisions following assessment with severity questionnaires suggested that GPs do not decide on drug treatment or referral for depression on the basis of questionnaire scores alone. Rates of treatment were similar for patients whether they were assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) or the depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale (HAD-D), despite the fact that those two measures assigned markedly different proportions of patients to the moderate to severe group regarded as needing treatment or referral.6

How this fits in

The Quality and Outcomes Framework in the UK rewards GPs for using validated questionnaire measures of severity of depression at the outset of treatment and more recently for follow-up. This interview study highlights GP concerns about how best to deploy such measures in practice without compromising the doctor–patient relationship and the use of clinical intuition and practical wisdom.

This paper reports on a qualitative interview study of GP views of the use of severity questionnaires in the diagnosis and management of depression. Previous findings are reported elsewhere.7 The key research question was ‘what do GPs think about the use of severity measures for depression in general practice?’.

Understanding how GPs conceptualise the use of severity questionnaires for depression is important for two reasons. First, their conceptualisations can have implications for how the questionnaires are used in practice. Second, an increased understanding of GP views provides an opportunity to identify potential problems associated with the use of depression measures in general practice. The current paper is timely and remains relevant in the broader context of the recent integration of the DEP 3 indicator to the QOF depression indicator set, which requires GPs to invite patients diagnosed with mild to moderate depression to repeat severity questionnaire measures at 5 and 12 weeks post-diagnosis.8

METHOD

Sampling

The sampling frame was 38 general practices in three locations in England (based around university centres in Southampton, Liverpool, and Norwich), which also took part in a quantitative study of the introduction of depression-severity questionnaires.6

Within the total sample of participating GPs, a maximum variation approach was used: variation by sex, years of experience, full-time/part-time, trainer/non-trainer, geographical location, and size of practice. Interviews continued until no new themes emerged.

Data collection

Open-ended, in-depth interviews were conducted by three researchers, at a site of the participant's choosing. Interviews used a semi-structured topic guide providing broad prompts to explore key issues derived from the literature (Box 1). These included views on intended and unintended consequences of the introduction of the depression severity indicator. GP responders were asked for concrete examples to support responses about diagnostic and therapeutic decision making. All interviews were audiorecorded and transcribed verbatim.

Box 1 Key areas of topic guide for GP interviews

Two key areas were addressed. The first focused on the GP's experience of using questionnaire indicators to help with the diagnosis and management of depression. The second area focused on the GP's views on the aims of depression indicators and the opportunities and challenges associated with their use.

Experiences of using depression indicators in practice

Could you tell me about your experiences of using severity indicators for depression?

Looking back at these particular examples, did you experience any difficulties or barriers when using the indicator?

Looking back at these particular examples, were there any factors that were particularly helpful or enabled your use of the indicator?

Have you ever felt that using a scored questionnaire about depression affected the interaction between you and a patient (positively/negatively)?

Where do you tend to ask patients to complete the questions?

Do you tend to use measures at the outset of treatment, as specified in the contract?

Views about the use of depression indicators in practice

-

7.

In your view, what are the key aims of the use of depression indicators?

-

8.

In your view, what are the key threats and challenges associated with the use of depression indicators?

-

9.

How could the challenges you have discussed be addressed?

-

10.

In general, do you consider depression measures to be useful?

Conclusion

-

11.

Are there any other relevant issues we haven't covered that you would like to mention?

Analysis

Three researchers analysed transcribed interviews using the principles of constant comparison.9 Analysis involved deconstructing each interview to identify primary issues and categories (open coding). These categories were compared to others within the transcript, and across other transcripts, and to concepts within the existing literature. Categories were cross-linked to generate new meanings and concepts (axial coding), and these were used to generate themes (selective coding).

Once a provisional list of themes had been derived, three different researchers reviewed 10 to 15 interview transcripts to test the plausibility, validity, relevance, and consistency of coding. Discussion over many weeks led to consensus themes. Exemplary quotations (Q1, Q2 etcetera) have been extracted from transcribed interviews and placed in boxes (Boxes 2–4) to illustrate key issues, and each quotation includes line numbers to indicate where they were originally located in the main transcribed interviews.

Box 2 Possible effects on the doctor–patient relationship

Building and maintaining the doctor–patient relationship

Q1: ‘I think it's quite important that you don't lose the sort of, the, you know, the one-to-one interpersonal relationship with somebody and I think that's probably quite important if you're supporting someone with a depression.’ (GP29: 185–187)

Q2: ‘It's difficult ‘cause a lot of picking up depression is about rapport and about patients feeling comfortable and establishing a relationship.’ (GP03: 25–27)

Dichotomising activities: ticking boxes for the QOF versus building rapport with patients

Q3: ‘Erm it's a bit it's a bit awkward in terms of the consultation in that you know you've had a good conversation with somebody you've built up a rapport and then you put a piece of paper in front of them.’ (GP09: 59–63)

Q4: ‘Getting them to do the tick box thing at the end of all that, when they've already bared their soul, can sometimes be a bit … intrusive, I find.’ (GP08: 46–47)

Q5: ‘I just refuse to sort of say to someone who I've been talking to who I think is depressed, now sit here and fill in this form. [I: Mmm] So what I would tend to do is give them a form and say, look, take it away at your leisure.’ (GP06 14–17)

Trivialising the relationship and losing focus

Q6: ‘If you have a very loaded consultation, very cathartic … the HAD scale can appear to trivialise the depth of the emotions that are being expressed.’ (GP01: 62–64)

Q7: ‘It's important for it not to overtake the other sort of human aspects of the consultation.’ (GP01: 145)

Box 4 How to deploy the severity questionnaire in interaction

Interfering with the consultation process: GP perspective

Q1: ‘Some, some times it just isn't appropriate in the context, you know, it just, just, sort of … interferes with the consultation.’ (GP07: 266–270)

Q2: ‘The greatest challenge that I found is how to incorporate it tactfully into the consultation because I feel that when a patient comes with a first presentation of depression the consultation for me, the way the consultation flows is one of the most important things and I don't feel comfortable, straightaway with sort of issuing a box-ticking exercise … how the conversation flows from there is often quite critical in how your relationship subsequently develops and how the therapeutic relationship goes.’ (GP23: 6–15)

Q3: ‘I find talking to the patient and letting the patient tell me what's wrong with them much, letting them speak for their 7 or 8/9 minutes, is much more beneficial than actually saying, “stop, now you've said you're depressed I have to do a screening programme”.’ (GP33: 14–18)

Q4: ‘Where do you plonk those great big you know [I: yes] bombshells in the middle of a normal consultation with somebody [I: yeah] … I tend to get an idea about people without necessarily asking those questions.’ (GP22: 147–153)

RESULTS

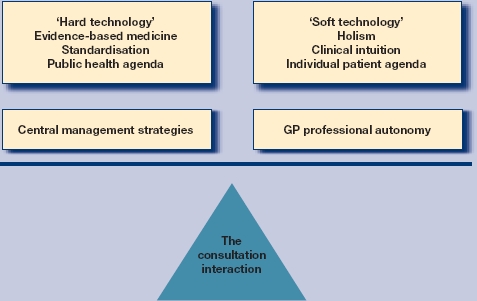

Thirty-four GPs were interviewed, and details are given in Table 1. All but one of the GPs were interviewed in their own surgeries. This paper presents a reflection of GP concerns about the measures, and these vary in nature from ideological (for example, concerns for holism) and political (for example, resistance of a ‘top down approach’ to innovation in service delivery), through to professional (for example, concerns for maintaining clinical intuition in diagnosis). Key concerns and their connection to the conduct of the consultation are summarised in Figure 1, and three concerns are discussed in the following sections.

Table 1.

GP sample characteristics (n = 34).

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 19 (56) |

| Female | 15 (44) |

| Age, years | |

| Range | 31–62 |

| Median | 45 |

| Mean | 44 |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 30 (88) |

| Asian-Indian | 4 (12) |

| Years in primary care/general practice | |

| Range | 0–28 |

| Median | 15 |

| Mean | 14 |

| Trainer | 7 (21) |

| Contract | |

| Full-time | 25 (74) |

| Part-time | 9 (26) |

| Location | |

| City | 29 (85) |

| Town | 2 (6) |

| Village/small town | 3 (9) |

| Single-handed | 7 (3) |

| Size of practice | |

| Small | 4 (12) |

| Medium | 8 (24) |

| Large | 22 (65) |

Figure 1.

Balancing care in the consultation.

Compromising the doctor–patient relationship

The interviews highlighted a fear that the doctor–patient relationship may become spoiled through the routinised embedding of questionnaire measures. Maintaining the doctor–patient relationship was a robust theme (Box 2: Q1). The majority of GPs reflected on what the score ‘did’ to the relationship and to rapport building. The score was (implicitly) conveyed as potentially making patients uncomfortable and as standing outside of the act of establishing a relationship (Box 2: Q2). When speaking about the use of severity questionnaires, GPs contrasted activities that epitomise rapport building, such as talking in-depth and at length, with tasks that are often viewed as ‘doctor centred’, bureaucratic, and insensitive, epitomised by the act of ticking boxes on a form (Box 2: Q3 and 4). For some, this contention precluded use of the questionnaires during the consultation, with GPs opting instead to send patients away to think about their responses and complete the instruments in their own time (Box 2: Q5).

In summary, the use of a severity questionnaire risked fracturing the delicate therapeutic function of the consultation, compromising patient catharsis from talking in depth, and trivialising patient problems through measurement (Box 2: Q6). It was constructed as undermining the ‘human’ element of the consultation (Box 2: Q7).

Threatening holistic practice and GP intuition

All of the GPs stressed the importance of evaluating a questionnaire score in the broader holistic context of the individual patient (especially in the case of mental health) (Box 3: Q1). In a similar vein to their accounts about preserving their relationship with patients, GPs discursively invoked a series of contrasts in which they compared, for example, information gleaned from detailed history taking with less thorough information derived from a HAD score (Box 3: Q2). The utility of a questionnaire score was viewed in the broader context of patients' individual and complex ‘life worlds’ (Box 3: Q3), and the inflexibility of the severity questionnaires was deemed to be a shortcoming (Box 3: Q4).

Box 3 Potential threat to holism and GP intuition

Unique requirements of patients with mental health problems

Q1: ‘Mental health, mental illness … more than most other illnesses are so patient specific and … how it affects their lives depends on what they're doing in their lives, depends on what their background is, might depend on family history and might depend on so many other factors, I think it's um … [completely] impossible to, to mechanise the assessments.’ (GP04: 158–162)

Dichotomising activities: ticking boxes versus detailed history taking

Q2. ‘The whole process of history taking, I felt, gave me the opportunity to assess their mental state, um, in a way that was really much more thorough than required by the use of a HAD.’ (GP07: 8–10)

Rendering reductionist measures relevant in a patient's broader context

Q3: ‘Sometimes … it doesn't follow in that they have er, drug use or something else which isn't taken into account and therefore I don't think the number's necessarily going to be as significant.’ (GP05: 20–23)

Q4: ‘I think if it had a negative it is very erm it doesn't allow you to adjust for individual situations.’ (GP31: 69–70)

Q5: ‘And again, like any other test, including biochemical or medical tests, there is a danger that you end up treating the result of the investigation rather than the patient themselves.’ (GP28: 9–11)

Q6: ‘I certainly would never make a decision to treat or not treat purely on the results of the score. I would, I would put the score into the sort of clinical context that I'd assessed.’ (GP07: 83–85)

Q7: ‘I think we'll be bringing up a whole … generation of doctors who will be very driven by ticking boxes.’ (GP32: 281–282)

Threat to GP skill and intuition?

Q8: ‘I'm not as convinced of the therapeutic value of those I have to say [I: Right] I personally find that a little bit more insulting [I: Aha]. Erm I'd like to think that if I was reviewing someone with a chronic illness [I: Mm] I would have the wherewithal to perhaps pick up other signals of depression.’ (GP 31: 347–375)

Fears of reductionism and loss of holism were complexly interwoven with a fear that GPs might come to rely too heavily on scores, and in the process jettison their intuition and clinical judgement (Box 3: Q5, 6, and 7). It seemed that contention between severity questionnaires and the goal of delivering individualised patient care was complexly driven by a concern for patient care and the preservation of professional intuition and judgement. ‘Asking those questions’ could be viewed as inferior to intuitively ‘getting an idea about people’ (Box 3: Q8).

Deploying the severity questionnaire in the consultation interaction

GP concerns seemed, in part, to be shaped by a very practical concern of precisely how and when a measure should be introduced, without intruding into the consultation (Box 4: Q1). The issue of timing the introduction of a questionnaire into the consultation seemed to pose some difficulty, and was intertwined with concerns about the possible impact a set of formal questions might have on the delicate interactional alliance between doctor and patient, and on GPs' ability to practise holistically (Box 4: Q2 and 3). Thus, the measure was not viewed as an integrated part of patient assessment and diagnosis (Box 4: Q4).

DISCUSSION

Summary of main findings

The QOF challenges current management strategies of depression and it is known that current management relies heavily on the prescribing of antidepressants (often in a situation where there is little else to offer patients). GPs are under pressure to ‘get it right’, and are undoubtedly more accountable than in previous years, and this can lead to conflict with parties ‘who threaten their autonomy, notably the state …’.10 Given these broader considerations, it is unsurprising perhaps that GPs have concerns about the micro-organisation of the consultation (the bedrock of general practice) and the deployment of the severity measures in that space, and unease about the impact changes to service delivery might have on their professional role and identity.

There were positives associated with the use of the severity questionnaire. Although interviewers did not ask about the suicide question in particular, the few GPs that raised the issue, described how the use of such questionnaires (especially the PHQ-9) at least provided a way of integrating a question about suicide into the GP consultation (GP05, GP14, GP15, GP32), and occasionally the answer to the question surprised them (GP08). However, it was described by one GP as disturbing to see a positive answer if the patient had already left the consulting room (GP08). This again feeds into the authors' suggestion that the way in which GPs use the instruments in or outside of the consultation is of great importance.

In their interviews, GPs prized elements of ‘patient-centred care’ including the use of their prior knowledge of patients, eliciting patient perspectives, and the need for a model of health and wellbeing that is inclusive of social context and relationships.11,12 While talking about the tension between the ‘hard technology’ of the questionnaire and the ‘soft technology’ of working with each unique patient,13 GPs discussed the interactional issue of precisely how to insert the ‘hard’ technology of the score into the ‘soft’ and delicate process-focused technology of the consultation. This practical consideration was significant.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Potential biases existed in the study's recruitment methods. Only interested GPs were likely to take part, so they may have tended to express stronger opinions, either positive or negative, than would be the norm. In terms of study methods, thematic analysis can result in the de-contextualisation of speakers' words, which may misrepresent the intended meaning as they appeared in the original sequential talk. However, great care was taken to analyse the participants' words in the broader context of the surrounding utterances, to ensure a fair interpretation. As with all interview studies, the kinds of data generated are limited. Interviews provide useful perspectives on events or experiences but cannot be windows on events as they occur. Moreover, interviewees seek to manage the impression they make.

Comparison with existing literature

In a previous paper,7 GP and patient views were compared and it was clear that patients were less worried about the validity and utility of questionnaire measures and more convinced of their worth. For example, patients described the use of the measures as adding objective evidential weight to GP judgement and intuition, as signalling validation of their experiences, and indicating positive GP investment of time to assess them carefully. While patients, like GPs, were keen to see scores used in a holistic way, they were not so concerned about the doctor–patient relationship. This is not so surprising, since it was evident that GP concerns were, in part, shaped by a concern to preserve their professional judgement and identity, and broader concerns about the political context in which new systems had been introduced and the way in which this had been done.

In terms of how to deploy the severity measures, May et al‘s study of psychiatrists’ views of tele-psychiatry helps us to understand this particular concern.14 The problem of tele-psychiatry, as reported by participants, did not solely reside in the ‘technical limitations or deficiencies of the tele-psychiatry system’, but rather the weakness resided in the system's ‘incompatibility with the set of practices that already constituted the ‘technology’ of the consultations’.14 In this study, GPs' ‘repertoires of resistance’15 similarly highlighted the ‘uneasy relationship between intuition and evidence’ derived from questionnaires.16

It is clear from this study that GPs managed the questionnaires differently, with some inviting patients to take them away, others completing them in waiting rooms and some completing the questionnaires with their patients in the consultation. Malpass17 and colleagues have suggested that GPs should go over the answers to individual questions with patients, to draw out the meaning of their responses. This resonates with the current findings and provides an important way for GPs to interpret the meaning of scores together with their patients.

Fairhurst and May18 explored GPs' views on what they find satisfying about consultations. They found that ‘[doctors'] reports of satisfying and unsatisfying experiences during consultations were primarily concerned with developing and maintaining relationships rather than with the technical aspects of diagnosis and treatment’. In line with this, it is not that surprising that in the present study the severity questionnaire for depression was construed as a symbol of standardisation, associated with a broader public health agenda and not so clearly about the individual patient agenda. The dual demands of rapport building and questionnaire completion were described as difficult.

As well as concerns about the doctor–patient relationship, GP concerns were clearly connected to a drive to defend their professional autonomy, which by definition involves independent and self-directing judgment. However, in pitting ‘hard’ (questionnaire) and ‘soft’ (consultation) technologies against each other, GPs produced a rather polarised opposition between severity questionnaires versus the role of the skilled GP and the (principled) ideology of holism. And yet, as Greenhalgh reminds us:

‘… the false dichotomy between evidence-based medicine and clinical intuition, with the former defined as the ‘scientific’ element, has no sound theoretical basis'.16

Indeed, the QOF guidance emphasises the importance of clinicians considering:

‘… family and previous history as well as degree of associated disability and patient preference in making an assessment of the need for treatment, rather than relying completely on a single symptom count’.2

Implications for future research and clinical practice

Perhaps two key and familiar issues lie at the heart of GP concerns: first, it might be that stakeholder engagement in the design, introduction, and continued execution of the QOF target has been sub-optimal. Second, it might also be that, by and large, there has been a lack of attention on process, of how the severity measures can best be embedded into practice.

GP reports suggested a limited sense of ownership of the service changes brought about through the QOF. May19 has similarly highlighted how the politics of evidence can ‘fail to respond to the contingencies of everyday practice in health and social care settings’. GP views in this study provide some tentative evidence to suggest that the introduction of the severity questionnaires did not fully consider the contingencies of everyday practice. This matters, for it is clear that a shared belief in and enthusiasm for new practices, procedures and technologies by those mandated to ensure their deployment in practice can enhance their integration.4,20

Thus, in part, GP resistance seemed to evolve not from an ideological objection to an ‘epistemological marriage between evidence-based medicine and Balint style consulting’,16 but from a much more practical unease about how, with their patients, they can best achieve such a marriage. This leads us to the second issue.

Social scientific findings indicate how relatively small differences in clinician behaviour can have ‘profound implications for diagnosis and treatment’.21,22 Hence, there is a certain logic in proposing that precisely how and when, in an ongoing trajectory of interaction, the topic of severity questionnaire completion is introduced by GPs should be considered, and guidance on how best to incorporate these new practices be offered. Precisely how GPs use the measures is likely to be consequential in terms of their satisfaction with the consultation, patient acceptability, and the utility and the meaning of the data generated. Certainly, empirical understanding of the use of measures in general practice could be enhanced by increasingly asking some of the tricky questions about process; attempting to explore how precisely they are used and whether/how different approaches might impact on outcome.

To summarise, knowledge of GPs' conceptualisations, their particular sensitivities and contentions and how these are expressed: increases our understanding of how GPs use and interpret measures in practice; and improves our understanding of factors that might be required to optimise and embed new QOF measures (for example, greater guidance on the process issues of how to use them in practice); and also, illuminates how the ideologies of rapport/’centredness'/’holism’ may be used as resources by practitioners to articulate the limits of new ‘technologies’ or modes of practice in primary care. Furthermore, embedded in GPs' critical narratives lies an implicit orientation to a need for recognition that some clinical work ‘is beyond easy definition, and that discretion and interpretation remain vital features of clinical practice’.23–25 As ‘… sociologists have observed, there is always a part of clinical practice that is beyond precise prediction, beyond the protocol or the exact risk calculation’.23 No evidence is ‘self-interpreting’ and its relevance and meaning is contextual and contingent.26

Most are accepting of these ideas, including the GPs in this study, but crucially what we seem to be lacking is systematically gathered examples of practitioners (with their patients) accomplishing a marriage between the art of diagnosis and management and the use of standard severity questionnaires. As Greenhalgh's16 work suggests, we need to open up the black box of clinical experience and judgement and begin to define how they interact with evidence. Opening up the black box will help to render visible and reportable the synergistic enactment of ‘evidence’ and ‘intuition’ and help to reveal very practical methods for optimising their integration in practice. Equally, for future QOF targets perhaps we need to look at our models of practitioner engagement to ensure the uneasy relationship between ‘evidence’, experience, and intuition is eased, and pilot their introduction accordingly.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the advice we received on the design, conduct, and interpretation of the study from Simon Gilbody, Michael Moore, Robert Peveler, Deborah Sharp, and Andre Tylee. Becky Rowles, clinical studies officer at the Mental Health Research Network North West hub, helped with patient recruitment.

Funding body

This study was funded by an unrestricted educational grant from Lilly, Lundbeck, Servier, and Wyeth pharmaceuticals. It also received funding from Southampton City Primary Care Trust and the Mental Health Research Network, East Anglia, West, and North West hubs. None of the above bodies had any role in study design; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of the paper; or the decision to submit this paper for publication. The study was sponsored by the University of Liverpool.

Ethical approval

Liverpool Paediatric Research Ethics Committee gave ethical permission for the study (reference 07/Q1502/23), and approval was obtained from local ethics committees and NHS trust research governance offices at all three sites.

Conflicts of interest

The study was funded by Lilly, Lundbeck, Servier, and Wyeth pharmaceuticals, manufacturers of antidepressants. Tony Kendrick has received fees for presenting at educational meetings from Lilly, Lundbeck, Wyeth, and Pfizer pharmaceuticals. Tony Kendrick and Christopher Dowrick are members of the mental health expert panel of advisors for the UK GP contract Quality and Outcomes Framework, which recommended the inclusion of the incentives for using depression severity questionnaires in the contract.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Depression. management of depression in primary and secondary care. Clinical Guideline 23. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.BMA and NHS Employers. Revisions to the GMS contract, 2006/07. Delivering investment in general practice. London: BMA and NHS Employers; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mangin D, Toop L. The Quality and Outcomes Framework: what have you done to yourselves? Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(539):435–437. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell SM, McDonald R, Lester H. The experience of pay for performance in english family practice: a qualitative study. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(3):228–234. doi: 10.1370/afm.844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeffries D. Ever been HAD? Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56(532):885–886. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kendrick T, Dowrick C, McBride A, et al. Management of depression in UK general practice in relation to scores on depression severity questionnaires: analysis of medical record data. BMJ. 2009;338:b750. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dowrick C, Leydon GM, McBride A, et al. Patients' and doctors' views on depression severity questionnaires incentivised in UK quality and outcomes framework: qualitative study. BMJ. 2009;338:b663. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.BMA, NHS Employers. Quality and Outcomes Framework guidance for GMS contract 2009/10. Delivering investment in general practice. London: BMA and NHS Employers; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silverman D. Communication and medical practice. London: Sage; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Britten N. Prescribing and the defence of clinical autonomy. Sociol Health Illn. 2001;23(4):478–496. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheraghi-Sohi S, Hole AR, Mead N, et al. What patients want from primary care consultations: a discrete choice experiment to identify patients' priorities. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(2):107–115. doi: 10.1370/afm.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughes JC, Bamford C, May C. Types of centredness in health care: themes and concepts. Med Health Care and Philos. 2008;11(4):455–463. doi: 10.1007/s11019-008-9131-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.May C, Ellis N. When protocols fail: technical evaluation, biomedical knowledge, and the social production of ‘facts' about a telemedicine clinic. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53(8):989–1002. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00394-4. 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.May C, Gask L, Atkinson T, et al. Resisting and promoting new technologies in clinical practice: the case of telepsychiatry. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(12):1889–1901. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00305-1. 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moreira T. Diversity in clinical guidelines: the role of repertoires of evaluation. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(9):1975–1985. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenhalgh T. Intuition and evidence – uneasy bedfellows? Discussion paper. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52(478):395–400. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malpass A, Shaw A, Kessler D, Sharp D. Concordance between PHQ-9 scores and patients' experiences of depression: a mixed methods study. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60(575):410–416. doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X502119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fairhurst K, May C. What general practitioners find satisfying in their work: implications for health care system reform. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(6):500–505. doi: 10.1370/afm.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.May C. Mobilising modern facts: health technology assessment and the politics of evidence. Sociol Health Illn. 2006;28(5):513–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2006.00505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.May C, Finch T. Implementing, embedding, and integrating practices: an outline of normalisation process theory. Sociology. 2009;43(3):535–554. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heritage J. Garfinkel and ethnomethodology. Cambridge and New York: Polity Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heritage J, Stivers T. Online commentary during the physical examination: a communication tool for avoiding inappropriate antibiotic prescribing? Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(2):313–320. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armstrong D. Conceptualising the patient: worth a second look. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002;7(4):242–247. doi: 10.1258/135581902320432787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McWhinney IR. The importance of being different. William Pickles Lecture, 1996. Br J Gen Pract. 1996;46(408):433–436. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gillies J. Perceptual capacity and the good GP: invisible, yet indispensible for quality of care. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(521):974–977. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hunter K. ‘Don't think zebras': uncertainty, interpretation, and the place of paradox in clinical education. Theor Med. 1996;17(3):225–241. doi: 10.1007/BF00489447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]