Abstract

Drawing on a symbolic-interaction perspective and a compensation model, the processes linking mother-and father-adolescent relationship qualities, deviant peer affiliations, and adolescents’ sexual intentions were investigated for 246 Mexican-origin youths born in the United States and in Mexico using multiple-group structural equation models. Deviant peer affiliations significantly mediated the relations between paternal acceptance and sexual intentions and between disclosure to mothers and sexual intentions for U.S.-born youths but not for Mexico-born youths. Findings highlight the importance of examining variability as a function of youth nativity.

Keywords: adolescence, adolescent peer relations, culture/race/ethnicity, Hispanic Americans, parent-adolescent relations, sexuality

Protecting adolescents from unintended pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections is particularly necessary for Latino youths because they have the highest teen birth rates compared to adolescents from other ethnic backgrounds (Ryan, Franzetta, & Manlove, 2005) and have higher rates of sexually transmitted infections than non-Latino Whites (National Vital Statistics, 2005). Despite these serious health risks, Latino adolescent sexuality is understudied. Given that Latinos are the largest and fastest-growing ethnic minority group in the country, and that 64% of that population is of Mexican descent (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009), it is particularly important to understand Mexican-origin youths’ sexual development. Further, because adolescents’ sexual intentions have been linked to their sexual behaviors (Gillmore et al., 2002), understanding the development of youths’ intentions to engage in sexual intercourse is a crucial step.

The present study extends research on the unique contributions of parents (particularly mothers) and peers to adolescent sexual development to investigate the interplay among mothers, fathers, and peers in youth well-being (Kerr, Stattin, Biesecker, & Ferrer-Wreder, 2003). Specifically, the first goal of this study was to examine deviant peer affiliations as a mediator of the links between maternal and paternal acceptance and adolescents’ disclosure to mothers and fathers and adolescents’ intentions for sex. Drawing on perspectives emphasizing within-group variability among ethnic minority youths (Fuligni, 2001), our second goal was to investigate adolescents’ nativity as a moderator of these associations.

Parent-Adolescent Relationship Qualities

Several theoretical perspectives and scholars of adolescent development have emphasized the importance of supportive parent – child relationships (e.g., acceptance, open communication, warmth) for adolescent adjustment (Steinberg, 2001). We draw on a symbolic interaction perspective (Blumer, 1969) and the literature on parental knowledge and monitoring in assessing the role of parent-adolescent acceptance and adolescents’ disclosure to parents in adolescents’ sexual intentions. From a symbolic-interaction perspective, the meaning of behaviors and roles, as well as the appropriateness of engaging in behaviors given a specific role, is created through interactions with others, such as parents. Moreover, parents are significant in helping their offspring internalize role-appropriate ways of behaving (Christopher, 2001); therefore, when parents are accepting, adolescents are more likely to internalize appropriate behavior and are at less risk of poor adjustment.

Interactions between parents and youths likely include adolescents’ disclosure, frequently referred to as a key aspect of parental monitoring (Kerr & Stattin, 2000). Such disclosure is an important way in which parents can gain knowledge about their children’s lives. In comparisons of multiple types of parental knowledge, adolescent disclosure (i.e., adolescents’ spontaneous provision of information about their daily lives) has been documented as the strongest predictor of adolescent adjustment, including fewer risky behaviors (Kerr & Stattin, 2000).

Still, our knowledge in this area is limited in that most studies examining associations between parent-adolescent relationship quality and youth adjustment have examined adolescents’ relationships with mothers (e.g., Trejos-Castillo & Vazsonyi, 2009); much less is known about the role of fathers, particularly in Latino families. Mothers and fathers have been described as having qualitatively different relationships with their children and may assume different parenting roles (Crockett, Brown, Russell, & Shen, 2007). For instance, Mexican-origin adolescents have reported more open communication and trust with mothers than with fathers (Crockett et al., 2007). Given such differences, it is important to consider the qualities of both mother-adolescent and father-adolescent relationships.

Deviant Peer Affiliations

Investigating the mediating processes by which parent-adolescent acceptance and adolescents’ disclosure to parents and adolescent sexuality are related is crucial for the development of interventions (Coie et al., 1993). An important mediator to investigate is the role of peers in sexual socialization (Christopher, 2001). Informed by a compensation hypothesis (Furman & Buhrmester, 1985), we explored whether deviant peer affiliations mediated the associations between parental acceptance and adolescents’ disclosure to parents and adolescents’ intentions to engage in sexual behaviors. According to a compensation hypothesis, if adolescents do not have emotionally close relationships with parents, then they are likely to seek out supportive relationships from others in their social networks, including peers (Furman & Buhrmester, 1985). Further, those adolescents may be more susceptible to involvement with deviant peers (Goldstein, Davis-Kean, & Eccles, 2005). In fact, researchers have found that deviant peer affiliations have been linked to problematic parenting (Simons, Cheo, Conger, & Elder, 2001) and less adolescent disclosure to parents (Kerr & Stattin, 2000). Deviant peer affiliations, in turn, were associated with problem behaviors, including risky sexual behaviors (Ary et al., 1999). Interactions with deviant peers reinforce adolescents’ own deviant behavior, which is related to greater involvement in problem behaviors and to increases in risky sexual behaviors over time (Patterson, Dishion, & Yoerger, 2000).

Evidence of deviant peer affiliations as a mediating process between parenting and problem behavior has been documented in Latino youths. Barrera, Biglan, Ary, and Li (2001) found, for example, that mothers’ inadequate monitoring was associated with Latino adolescents’ problem behavior via their deviant peer affiliations. We build on this research and existing theory by testing deviant peer affiliations as a mediator between both maternal and paternal acceptance and adolescents’ disclosure to mothers and fathers and adolescents’ sexual intentions. We expected parent-adolescent acceptance and adolescent disclosure to parents to be negatively associated with deviant peer affiliations, and in turn positively associated with adolescents’ intentions for sex. Although our analyses are cross-sectional and we cannot determine temporal precedence, previous work has shown that inept parenting is related to greater deviant peer affiliations over time (Simons et al., 2001) and that deviant peer associations were related to risky sex over time (Crockett, Rafaelli, & Shen, 2006), which lends support to our model.

Nativity as a Moderator

Scholars who study ethnic-minority youths have called for ethnic-homogeneous research designs that allow for the examination of variability within specific cultural groups (Garcia Coll et al., 1996). In this study, we investigated youth nativity as a moderator to assess whether the processes linking parent-adolescent relationship qualities, deviant peer affiliations, and adolescent sexual intentions differed for Mexican-origin youths born in the United States and for those born in Mexico. Although previous research has found no generational status differences in the links between mother-adolescent relationships and Latino youths’ risky sexual behaviors (Trejos-Castillo & Vazsonyi, 2009), the present study extends prior work in several ways. First, in this study, we investigate associations among mother-and father-adolescent relationships and youth sexuality and test the role of deviant peer affiliations as a mediator between parenting and youth sexuality. Second, our focus is on normative sexual development (i.e., youths’ intentions to engage in sex) rather than youths’ risky sexual behaviors (i.e., unprotected sex).

From a symbolic-interaction framework, individuals in a culture create similar meanings for objects, and those meanings or interpretations shape the actions of the individuals in the culture to create acceptable role behavior (Blumer, 1969). In addition, adolescents learn role expectations from their parents, and those expectations likely differ on the basis of youths’ nativity status. For instance, peer relationships have been recognized as an important part of adolescents’ social lives, particularly for adolescents living in the United States (Brown & Larson, 2002). Compared to other cultures, parents in the United States may promote and encourage their offspring’s associations with peers (Brown & Larson, 2002). In addition, it is important to recognize that Mexican-origin youths born in the United States are more likely to be exposed to socialization agents that endorse U.S. mainstream values such as the importance placed on peers, whereas adolescents born in Mexico will have relatively fewer experiences with socializing agents that endorse mainstream U.S. values, given their families’ relatively more limited time in the United States. To illustrate, in a study of Latino high school students, Mexico-born adolescents were significantly more resistant to peer pressure to engage in antisocial behaviors than were their U.S.-born counterparts (Bámaca & Umaña-Taylor, 2006). Thus, it is possible that peers play a stronger role in adolescents’ sexual intentions for youths born in the United States than for youths born in Mexico. Furthermore, given that Hispanic youths with positive peer groups engaged in fewer delinquent behaviors (Padilla-Walker & Bean, 2009), Mexico-born youths may be more likely to form relationships with positive, coethnic peers, which may serve a protective function against engaging in deviant behaviors.

Researchers also have shown that Mexican-origin adolescents born in Mexico have higher familism values (e.g., familism obligations, familism referent; Knight, Gonzales et al., 2010) than do Mexican-origin adolescents born in the United States. Because of the greater emphasis on familism values, Mexico-born adolescents may be more likely than U.S.-born adolescents to seek support from other family members (e.g., siblings, cousins) than from peers when they experience poor relationships with their parents, and those family members may be more influential on youths’ sexuality (East, Felice, & Morgan, 1993). Given the emphasis on peer culture in the United States, and the potentially greater emphasis on family for adolescents born in Mexico (Hardway & Fuligni, 2006), we anticipated that the mediating role of deviant peer affiliations between parent-adolescent relationship characteristics and adolescents’ sexual intentions would be stronger for Mexican-origin adolescents born in the United States than for those born in Mexico.

Current Study

In summary, the present study had two goals: (a) to investigate deviant peer affiliations as a mediator between parent-adolescent relationship qualities and Mexican-origin youths’ sexual intentions and (b) to examine nativity status as a moderator of those associations. Because several important background characteristics (e.g., age, gender, socioeconomic status [SES]) are linked to adolescents’ involvement in sexual activity, we included control variables in our models. Specifically, empirical data have shown greater involvement in sexual activity for high-SES youths (Trejos-Castillo & Vazsonyi, 2009), for boys, and for older youths (Guttmacher Institute, 2006).

Method

Participants

The data came from a study of family socialization and adolescent development in Mexican-origin families (Updegraff, McHale, Whiteman, Thayer, & Delgado, 2005). Data were collected during 2002 and 2003. The 246 participating families were recruited through schools in and around the Phoenix metropolitan area. Criteria for participation were as follows: (a) mothers were of Mexican origin; (b) a seventh grader was living in the home and not learning disabled; (c) an older sibling was living in the home (in all but two cases, the older sibling was the next oldest child in the family); (d) biological mothers and biological or long-term adoptive fathers lived at home (all nonbiological fathers had been in the home for a minimum of 10 years); and (e) fathers worked at least 20 hours per week. Most fathers (i.e., 93%) also were of Mexican origin.

To recruit families, letters and brochures describing the study (in both English and Span-ish) were sent to families, and bilingual staff made follow-up telephone calls to determine eligibility and interest in participation. Families’ names were obtained from junior high schools in five school districts and from five parochial schools. Schools were selected to represent a range of socioeconomic situations, with the proportion of students receiving free and/or reduced lunch varying from 8 percent to 82 percent across schools. Letters were sent to 1,856 families with a Hispanic seventh grader who was not learning disabled; however, for 396 families (21%), the contact information was incorrect and repeated attempts to find updated information unsuccessful. Eligible families (n = 421) represented 23% of the initial rosters (n = 1856), and 32% of those we were able to contact and screen (n = 1314). Of those eligible, 284 agreed to participate (67% of eligible families), 95 refused (23% of eligible families), and 42 (10% of eligible families) had moved between the initial screening and schedule call and no updated contact information was available. In total, 246 families (of the 284 who agreed to participate) completed interviews. We were unable to complete interviews with 38 families who were unwilling to participate or were not home (repeatedly) for the interview. Because we had surpassed our original target sample (n = 240), we did not continue to recruit these families.

Families represented a range of education and income levels, from poverty to upper class. Median family income was $40,000 (for two parents and an average of 3.39 children). Mothers and fathers had completed an average of 10 years of education (M = 10.34; standard deviation [SD] = 3.74 for mothers, and M = 9.88; SD = 4.37 for fathers). Sixty-six percent of mothers and 68% of fathers completed the interview in Spanish. Most parents were born outside the United States (71% of mothers and 69% of fathers). For parents born in Mexico, mothers and fathers had lived in the United States an average of 12.38 (SD = 8.86) and 15.18 (SD = 8.78) years, respectively. Older siblings were 50% female and 15.70 (SD = 1.6) years of age on average. Forty-seven percent of older siblings were born outside the United States (i.e., Mexico born n = 114; U.S. born n = 132), and 82% were interviewed in English. Because there was little variability in younger siblings’ sexual intentions, the present analyses focused only on older siblings (M of sexual intentions = 2.15; SD = 1.11).

Procedures

Data were collected during home interviews, which lasted an average of 2 hours for adolescents and 3 hours for parents. Parents reported on background characteristics and family relationships, and adolescents reported on their relationships with parents, peers, and their intentions to engage in sexual intercourse. Bilingual interviewers conducted individual interviews using laptop computers and by reading questions aloud to participants.

Measures

All measures were forward- and back-translated for local Mexican dialect (i.e., among Latino subgroups). A third Mexican-origin translator reviewed all measures and resolved discrepancies.

Demographic information, including adolescents’ and parents’ nativity, family income, and adolescents’ age were collected from mothers and fathers during in-home interviews. Family income was transformed by taking the log to correct for skewness.

Adolescents reported on their sexual intentions using a 5-item measure ranging from 1 (very unlikely/very unsure) to 5 (very likely/very sure) adapted from East’s (1998) work with Latino youths. Items were averaged to create the scale score. The measure for the current study included an additional item—“How likely is it that you would try to persuade someone to have sex with you?”—to appropriately assess boys’ sexual intentions. Another example item is “How likely is it that you will have sexual intercourse in the next year?” Scores ranged from 1 to 5 for U.S.-born youths and from 1 to 4.6 for Mexico-born youths (Cronbach’s α = .86).

Adolescents rated parent-adolescent acceptance separately for mothers and fathers using an 8-item acceptance subscale of the Children’s Reports of the Parent Behavior Inventory measure (Schwarz, Barton-Henry, & Pruzinsky, 1985), which has been demonstrated to be equivalent across ethnic groups for Latinos, African Americans, and European Americans (Knight, Tein, & Shell, 1992). Youths rated items on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). Items were averaged to create the scale score. A sample item is “My mother/father speaks to me in a warm and friendly voice.” Scores ranged from 1 to 5 for both U.S.- and Mexico-born youths (Cronbach’s α = .89 and .93 for mothers and fathers, respectively).

Reports of adolescent disclosure to parents were collected from adolescents using an average rating of the 5-item child disclosure subscale of the Parents’ Sources of Knowledge Measure (Kerr & Stattin, 2000). A sample item is “Do you tell your mother/father about how your day went without being asked?” Cronbach’s α = .69 for disclosure to mothers, and scores ranged from 1.67 to 4.83 for U.S.-born youths and from 1 to 5 for Mexico-born youths. Cronbach’s α = .65 for disclosure to fathers and scores ranged from 1 to 5 for U.S.-born youths and from 1.5 to 5 for Mexico-born youths.

Adolescents rated their deviant peer affiliations using a 5-item scale adapted for use with ethnic minority youths (Barrera et al., 2001). Sample items included “How many of your friends have gotten drunk or high?” and “How many of your friends have lied about their age to buy or do things?” Items were averaged for the scale score; Cronbach’s α = .75. Scores ranged from 1 to 4.6 for U.S.-born youths and from 1 to 4.4 for Mexico-born youths.

Analytic Plan

Multiple-group structural equation modeling (SEM) procedures were used to test the associations among parent-adolescent relationship qualities (i.e., maternal acceptance, paternal acceptance, disclosure to mothers, disclosure to fathers), deviant peer affiliations, and sexual intentions for Mexican-origin youths born in the United States and in Mexico. Family income, adolescent age, and adolescent gender were included as control variables. Covariances among parent-adolescent relationship qualities, parent-adolescent relationship qualities and family income, parent-adolescent relationship qualities and adolescent age, and parent-adolescent relationship qualities and adolescent gender were estimated. Further, all direct effects were included in the models. Multiple-group analyses permitted examination of youth nativity as a moderator to determine whether path coefficients varied by nativity (Kline, 1998). With procedures that Kline (1998) suggested, if the partially constrained model resulted in a poorer fit (according to the χ2 difference test and other fit indices), it would suggest that the path estimates constrained to be equal in this model should not, in fact, be constrained to be equal to one another. Acceptable model fit was determined by a ratio of χ2 to degrees of freedom of less than 3 (Kline, 1998), values greater .90 on the comparative fit index (CFI), and values less than .08 for the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Kline, 1998). The selection of the final model was based on the χ2 difference tests and model fit indices. Mediation analyses were conducted using the bias-corrected bootstrap method (see MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004) in MPlus 4.21. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and correlations by youth nativity.

Table 1.

Correlations for Study Variables for U.S.-Born Adolescents (Above Diagonal; n = 132) and Mexico-Born Adolescents (Below Diagonal, n = 114)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Adolescent age | — | .09 | −.02 | .38** | −.10 | −.16 | .01 | −.03 | .33** |

| 2. Adolescent gendera | −.26* | — | −.20* | .44** | −.06 | −.04 | −.31** | −.08 | .19* |

| 3. Family incomeb | .00 | −.01 | — | −.17 | .16 | .14 | .21* | .13 | −.10 |

| 4. Sexual intentions | .14 | .50** | −.11 | — | −.32** | −.23** | −.39** | −.21* | .63** |

| 5. Maternal acceptance | .01 | −.06 | .12 | −.11 | — | .51* | .38* | .32* | −.25** |

| 6. Paternal acceptance | −.14 | .14 | .10 | −.01 | .47** | — | .21* | .69** | −.26** |

| 7. Disclosure to mothers | .11 | −.20* | .00 | −.10 | .60** | .36** | — | .47** | −.25** |

| 8. Disclosure to fathers | −.04 | .06 | .00 | .01 | .35** | .60** | .50** | — | −.17 |

| 9. Deviant peer affiliations | −.07 | .10 | .15 | .16 | −.13 | −.17 | −.16 | −.14 | — |

| M U.S. born | 15.66 | 1.54 | 69,789.22a | 2.26 | 3.96 | 3.58 | 3.17 | 2.97 | 2.11a |

| SD | 1.58 | .50 | 54,842.84 | 1.21 | .81 | .96 | .77 | .82 | .81 |

| M Mexico born | 15.75 | 1.46 | 33,956.03a | 2.03 | 3.95 | 3.58 | 3.29 | 3.05 | 1.92a |

| SD | 1.49 | .50 | 16,833.30 | .98 | .78 | 1.01 | .78 | .74 | .78 |

Boys.

Means are for untransformed variable.

Means are significantly different.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Results

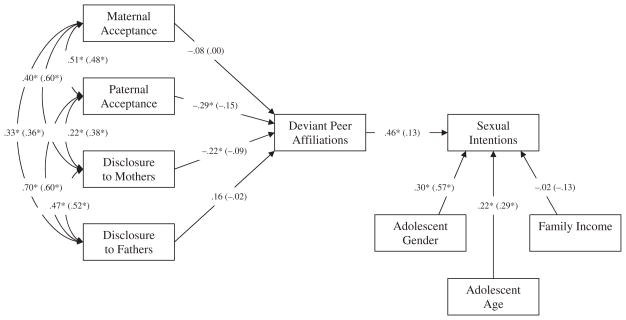

The initial estimated model (i.e., the unconstrained model) allowed paths and covariances to be freely estimated across nativity groups. This model adequately fit the data (Table 2, Figure 1). In line with previous work, older adolescents and boys reported greater intentions for sexual intercourse (Guttmacher Institute, 2006). There were several hypothesized paths that were significant for the U.S.-born group but not the Mexico-born group. Specifically, paternal acceptance and disclosure to mothers were negatively related to youths’ affiliations with deviant peers, and deviant peer affiliations were positively associated with sexual intentions only for U.S.-born youths.

Table 2.

Fit Indices for Models (N = 246)

| Adolescent Report | χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | RMSEA | Δχ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unconstrained | 18.83 | 6 | 3.14 | .93 | .13 | |

| Partially constrained | 29.56 | 15 | 1.90 | .92 | .09 | 10.73 (9) |

| Deviant peer affiliations → Sexual intentions constrained | 44.28 | 16 | 2.77 | .84 | .12 | 14.72 (1)a* |

| Paternal acceptance → Deviant peer affiliations constrained | 30.06 | 16 | 1.88 | .92 | .09 | .50 (1)a |

| Disclosure to mothers → Deviant peer affiliations constrained | 30.42 | 16 | 1.90 | .92 | .09 | .86 (1)a |

Comparison model (based on Δχ2) is the partially constrained model.

p < .05.

Figure 1.

Unconstrained Model.

Note: Standardized coefficients presented for youths born in the United States (and Mexico). *p < .05.

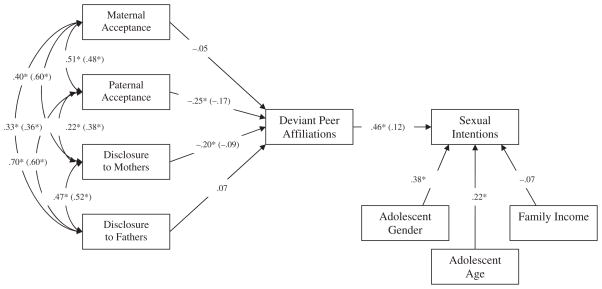

A second model was tested (i.e., partially constrained model) in which only the paths that were either significant for both groups (i.e., from adolescent gender to sexual intentions and from adolescent age to sexual intentions) or nonsignificant for both groups (i.e., paths from maternal acceptance to deviant peer affiliations, disclosure to fathers to deviant peer affiliations, and family income to sexual intentions) were constrained to be equal across nativity groups; put differently, paths that were significant for one group but non-significant for the other group were left freely estimated in this partially constrained model (i.e., paths from paternal acceptance to deviant peer affiliations, disclosure to mothers to deviant peer affiliations, and deviant peer affiliations to sexual intentions; Kline, 1998). The covariances among the exogenous variables and the exogenous variables and control variables were not constrained across groups (Kline, 1998). The partially constrained model fit the data well (see Table 2), and the χ2 difference test comparing the partially constrained model to the initial unconstrained model indicated that the two models were not significantly different from each other (Δχ2 (9) = 10.73, ns). The partially constrained model was selected as the final model because it was more parsimonious (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Partially Constrained Model.

Note: Sandardized coefficients presented for youths born in the United States (and Mexico). *p < .05.

As a final, more stringent test of significant differences in path estimates between the two nativity groups, several additional models were tested in which paths that appeared to differ in significance for the two nativity groups (i.e., significant for one group and nonsignificant for the other group) were constrained to be equal across groups (Kline, 1998). Each path was tested individually (see Table 2) such that the original partially constrained model was compared with a model in which one of the originally freely estimated paths was set to be equal across nativity groups (Kline, 1998). Using this strategy, findings revealed that the only path that was significantly different for U.S.- and Mexico-born youths was the path from deviant peer affiliations to sexual intentions. That is, constraining this path to be equal across nativity groups resulted in a significantly poorer model fit, as evidenced by a significant χ2 difference between this model (i.e., model in which the path from deviant peer affiliations to sexual intentions was constrained across groups) and the partially constrained model (Figure 2). Constraining all other paths to be equal did not result in poorer model fit when compared with the partially constrained model in Figure 2.

The final model (i.e., partially constrained model; see Figure 2) indicated that for both U.S.- and Mexico-born youths, boys and older adolescents reported greater sexual intentions than girls and younger adolescents. For the U.S.-born group only, deviant peer affiliations were positively related to sexual intentions. Given that this path was significant for U.S.-born youths, we tested deviant peer affiliations as a mediator of the links between paternal acceptance and disclosure to mothers and sexual intentions for youths born in the United States. Direct paths between paternal acceptance and sexual intentions and disclosure to mothers and sexual intentions were included. The two mediation paths that were tested were significant: (a) from paternal acceptance to deviant peer affiliations to sexual intentions (indirect effect = −.12, 95% confidence interval (CI) = −.27, −.03); and b) from disclosure to mothers to deviant peer affiliations to sexual intentions (indirect effect = −.09, 95% CI = −.29, −.02).

Additional Analysis

Given that there is substantial literature on generational status as a source of within-group variability (Trejos-Castillo & Vazsonyi, 2009), we ran a follow-up analysis to determine whether the patterns of associations differed among later-generation youths (e.g., second, third). We estimated an additional model in which youths’ generational status (measured as a function of youths’, parents’, and grandparents’ places of birth) was included as a control variable. This model was estimated only for U.S.-born youths, as there was no variability in generation status for Mexico-born youths. Model fit was acceptable (χ2(13) = 26.41; CFI = .90; RMSEA = .09). Generational status was negatively related to sexual intentions, but the patterns among parent-adolescent relationship qualities, deviant peer affiliations, and youths’ sexual intentions were identical to the models discussed above.

Discussion

Theoretical and empirical evidence reveals that both parents and peers are important socializing agents of adolescent sexuality (e.g., Gilliam, Berlin, Kozloski, Hernandez, & Grundy, 2007). Using principles from symbolic interaction theory (Blumer, 1969) and a compensation model (Furman & Buhrmester, 1985), this study extends prior work linking mother-adolescent relationship quality and sexuality for Latino youths (Trejos-Castillo & Vazsonyi, 2009) in several ways. First, this study contributes to the understanding of adolescent sexuality by concurrently considering the interrelated roles of mothers, fathers, and peers in adolescents’ sexual intentions. Second, we highlighted within-group variability among Mexican-origin adolescents by using an ethnic-homogeneous design and testing youth nativity status as a moderator of the associations among parent-adolescent relationships, deviant peer affiliations, and youths’ sexual intentions. Finally, we investigated adolescents’ relationships with both mothers and fathers, given the lack of attention to fathers in Latino families.

Role of Parent Gender

There were some similarities in the findings for mothers and fathers but also an important difference that emerged for U.S.-born youths that highlights the potentially unique roles that mothers and fathers may play in their young adolescents’ lives. Specifically, for mothers, deviant peer affiliations mediated the link between adolescent disclosure to mothers and sexual intentions; whereas for fathers, deviant peer affiliations mediated the link between father-adolescent acceptance and sexual intentions. This pattern is consistent with prior qualitative work on mothers’ and fathers’ distinct roles in Mexican-origin youths’ lives (Crockett et al., 2007), such that Mexican-origin adolescents reported greater levels of open communication about daily activities and trust in their relationships with mothers than with fathers, and adolescents reported that fathers were important providers of instrumental, financial, and indirect emotional support, such as showing interest in youths’ lives (Crockett et al., 2007). It may be communication about day-to-day activities with mothers and the emotional context of the relationship with fathers that are most salient for these youths. Together, the pattern of findings highlight that, from adolescents’ perspectives, different aspects of their relationships with their mothers and fathers are linked to their deviant peer affiliations, and in turn, their intentions for sexual involvement.

Process Differences for U.S.-Born and Mexico-Born Youths

Fuligni (2001) has emphasized process differences based on youths’ nativity status. In the present study, we found some differences in the processes linking parent-adolescent relationship qualities and adolescents’ sexual intentions based on youth nativity. In particular, for Mexican-origin youths born in the United States, deviant peer affiliations mediated the relation between parent-adolescent relationship qualities and sexual intentions. Specifically, lower levels of acceptance with fathers and lower levels of disclosure to mothers were related to greater deviant peer affiliations, and greater deviant peer affiliations were linked to greater intentions for sex. These findings are consistent with a compensation hypothesis (Furman & Buhrmester, 1985) and previous research showing that when youths do not have supportive relationships with parents, they are likely to seek out support from other individuals in their social networks (e.g., peers; Steinberg, 2001) and are also at greater risk for deviant peer affiliations (Goldstein et al., 2005). This study extends prior work by documenting deviant peer affiliations as a significant mediator of the associations between mother-and father-adolescent relationship characteristics and U.S.-born Mexican-origin youths’ intentions for sex.

The processes linking parents and peers to adolescents’ sexual intentions were not significant for Mexico-born youths; therefore, other crucial factors not included in this study may be important predictors of Mexico-born youths’ intentions for sex. For youths born in Mexico, peer relationships may not be as salient as other relationships, such as those with siblings and extended family members. Mexican-immigrant youths place greater importance on family obligations and assistance than do U.S.-born youths (Hardway & Fuligni, 2006), which highlights the importance of the family for youths born in Mexico. The inclusion of siblings, cousins, and other extended family members as socializing agents of youth sexuality among Mexican-immigrant youths will be important in future work (see East et al., 1993). Expanding on this point, it may be the case that, because of Mexico-born youths’ higher familism values (Knight, Gonzales et al., 2010), collective socialization (i.e., the combination of relationships with parents, siblings, and extended family members) is a more important predictor of youths’ sexual intentions than individual relationship qualities. In addition, other research has documented that Hispanic youths who affiliate with positive peer groups engage in fewer risky behaviors (Padilla-Walker & Bean, 2009). Mexico-born adolescents may be more likely to interact with coethnic positive peer groups that serve a protective function.

Limitations, Contributions, and Directions for Future Research

The present study offers several contributions to the literature; however, it is important to consider these strengths within the limitations of the study as a guide for future research. Only adolescent self-reports were used, and other reporters (e.g., parents) or observational data on the parent-adolescent relationship will contribute to the literature on Mexican-origin youth sexuality by providing diverse perspectives of relationship experiences and reducing shared method variance. The study sample was not intended to be representative of the U.S. Mexican-origin population. Instead, because of our focus on the roles of mothers and fathers, the sample was composed of two-parent Mexican-origin families living in the Southwest. Future studies should replicate these findings in families of diverse structures (e.g., remarried), from geographic regions, and from different Latino subgroups (e.g., Puerto Rican) to better understand the roles of mothers and fathers in adolescents’ sexuality. Our findings, which show that different dimensions of adolescents’ relationships with mothers versus fathers (i.e., acceptance and disclosure) were linked to their deviant peer affiliations, underscore the importance of future efforts to understand how relationships with mothers and fathers, uniquely and in combination, are linked to adolescents’ sexuality.

A different process emerged in the link between parent-adolescent relationship qualities and youths’ intentions for sex through deviant peer affiliations for Mexican-origin youths as a function of youth nativity status, after controlling for family income. These findings represent a first step in understanding within-group variability in processes linking parents and peers to youth sexuality for Mexican-origin youths. In future work, it will be important to disentangle the role of culture and income, two sociocultural factors that are often confounded in studies of ethnic-minority youths, and to explore how other aspects of youths’ cultural experiences (e.g., familism values) are related to the associations among parent-adolescent relationship characteristics, deviant peer affiliations, and youth sexuality. Further, investigating other aspects of the parent-adolescent relationship, such as parental control, solicitation, and supervision or monitoring of activities is necessary. Finally, this study was cross-sectional. Examining reciprocal and longitudinal associations linking the paths among parent-adolescent relationship characteristics, peer processes, and intentions for sex is an important avenue of future research.

Conclusion

The present study responded to the need for research investigating the indirect links between parent-adolescent relationship qualities and adolescent sexuality (Kerr et al., 2003). Given the ethnic-homogeneous design, this study stressed the variability in these processes in a Mexican-origin youth sample by making a within-group comparison of how relationships with parents and peers were associated with youths’ intentions to engage in sexual intercourse for youths born in the United States versus Mexico. This examination revealed that the hypothesized model was most applicable for youths born in the United States and that different processes may be at work linking parent-adolescent relationship qualities to adolescents’ sexual intentions for immigrant Mexican youths. Finally, by exploring the relationships that youths have with both mothers and fathers, the unique contributions of mothers and fathers to youths’ intentions to engage in sexual intercourse emerged.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the families and youths who participated in this project and to the following schools and districts that collaborated: Osborn, Mesa, and Gilbert school districts, Willis Junior High School, Supai and Ingleside middle schools, St. Catherine of Sienna, St. Gregory, St. Francis Xavier, St. Mary-Basha, and St. John Bosco. We thank Susan McHale, Ann Crouter, Mark Roosa, Nancy Gonzales, Roger Millsap, Ji-Yeon Kim, Jennifer Kennedy, Lorey Wheeler, Devon Hageman, Melissa Delgado, Emily Cansler, and Lilly Shanahan for their assistance in conducting this investigation, and Sandra Simpkins and Lorey Wheeler for their comments on the article. Funding was provided by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant No. R01HD39666 (Kimberly Updegraff, principal investigator; Ann C. Crouter and Susan M. McHale, co-principal investigators; Mark Roosa, Nancy Gonzales, and Roger Millsap, coinvestigators) and the Cowden Fund to the School of Social and Family Dynamics at Arizona State University.

Contributor Information

Sarah E. Killoren, Email: sarah.killoren@colostate.edu.

Kimberly A. Updegraff, Email: kimberly.updegraff@asu.edu.

F. Scott Christopher, Email: scott.christopher@asu.edu.

Adriana J. Umaña-Taylor, Email: adriana.umana-taylor@asu.edu.

References

- Ary DV, Duncan TE, Biglan A, Metzler CW, Noell JW, Smolkowski K. Development of adolescent problem behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1999;27:141–150. doi: 10.1023/a:1021963531607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bámaca MY, Umaña-Taylor AJ. Testing a model of resistance to peer pressure among Mexican-origin adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35:631–645. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Biglan A, Ary D, Li F. Replication of a problem behavior model of American Indian, Hispanic, and Caucasian youth. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2001;21:133–157. [Google Scholar]

- Blumer H. Symbolic interactionism perspective and method. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB, Larson RW. The kaleidoscope of adolescence: Experiences of the world’s youth at the beginning of the 21st century. In: Brown BB, Larson RW, Saraswathi TS, editors. The world’s youth: Adolescence in eight regions of the globe. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Christopher FS. To dance the dance: A symbolic interactional exploration of premarital sexuality. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Watt NF, West SG, Hawkins JD, Asarnow JR, Markman HJ, et al. The science of prevention: A conceptual framework and some directions for a national research program. American Psychologist. 1993;48:1013–1022. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.10.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett LJ, Brown J, Russell ST, Shen Y. The meaning of good parent – child relationships for Mexican American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17:639–668. [Google Scholar]

- Crockett LJ, Rafaelli M, Shen Y. Linking self-regulation and risk proneness to risky sexual behavior: Pathways through peer pressure and early substance use. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16:503–525. [Google Scholar]

- East PL. Racial and ethnic differences in girls’ sexual, marital, and birth expectations. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:150–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- East PL, Felice ME, Morgan MC. Sisters’ and girlfriends’ sexual and childbearing behavior: Effects on early adolescent girls’ sexual outcomes. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1993;55:953–963. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ. A comparative longitudinal approach to acculturation among children from immigrant families. Harvard Educational Review. 2001;71:566–578. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Children’s perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21:1016–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Coll CG, Crnic K, Lamberty G, Wasik BH, Jenkins R, Garcia HV, McAdoo HP. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67:1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliam ML, Berlin A, Kozloski M, Hernandez M, Grundy M. Interpersonal and personal factors influencing sexual debut among Mexican-American young women in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2007;41:495–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillmore MR, Archibald ME, Morrison DM, Wilsdon A, Wells EA, Hoppe MJ, Nahom D, Murowchick E. Teen sexual behavior: Applicability of the theory of reasoned action. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:885–897. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein SE, Davis-Kean PE, Eccles JS. Parents, peers, and problem behavior: A longitudinal investigation of the impact of relationship perceptions and characteristics on the development of adolescent problem behavior. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:401–413. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttmacher Institute. Facts on American teens’ sexual and reproductive health. New York: Author; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hardway C, Fuligni AJ. Dimensions of family connectedness among adolescents with Mexican, Chinese, and European Backgrounds. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:1246–1258. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, Stattin H. What parents know, how they know it, and several forms of adolescent adjustment: Further support for a reinterpretation of monitoring. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:366–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, Stattin H, Biesecker G, Ferrer-Wreder L. Relationships with parents and peers in adolescence. In: Lerner RM, Easterbrooks MA, Mistry J, editors. Handbook of psychology: Developmental psychology. Vol. 6. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2003. pp. 395–419. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Gonzales NA, Saenz DS, Bonds DD, Germán M, Deardorff J, Roosa MW, Updegraff KA. The Mexican American cultural values scale for adolescents and adults. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2010;30:444–481. doi: 10.1177/0272431609338178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Tein JY, Shell R. The cross-ethnic equivalence of parenting and family interaction measures among Hispanic and Anglo-American families. Child Development. 1992;63:1392–1403. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Vital Statistics Report. Revised birth and fertility rates for the 1990s and new rates for Hispanic populations, 2000 and 2001: United States. 2005 Retrieved September 10, 2005, from Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics, http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr51/nvsr5112.pdf. [PubMed]

- Padilla-Walker LM, Bean RA. Negative and positive peer influence: Relations to positive and negative behaviors for African American, European American, and Hispanic adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 2009;32:323–337. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Dishion TJ, Yoerger K. Adolescent growth in new forms of problem behavior: Macro- and micro-peer dynamics. Prevention Science. 2000;1:3–13. doi: 10.1023/a:1010019915400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan S, Franzetta K, Manlove J. Hispanic teen pregnancy and birth rates: Looking behind the numbers (Publication No. 2005-01) Child Trends Research Brief. 2005 Retrieved from http://www.childtrends.org.

- Schwarz JC, Barton-Henry ML, Pruzinsky T. Assessing child-rearing behaviors: A comparison of ratings made by mother, father, child, and sibling on the CRPBI. Child Development. 1985;56:462–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Cheo W, Conger RD, Elder GH. Quality of parenting as mediator of the effect of childhood deviance on adolescent friendship choices and delinquency: A growth curve analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. We know some things: Parent – adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Trejos-Castillo E, Vazsonyi AT. Risky sexual behaviors in first and second generation Hispanic immigrant youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:719–731. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9369-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, McHale SM, Whiteman SD, Thayer SM, Delgado MY. Adolescents’ sibling relationships in Mexican American families: Exploring the role of familism. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:512–522. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau News. Hispanic Heritage Month 2009. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/releases/archives/factsforfeaturesspecialeditions/013984.html.