Abstract

An imbalance in circulating pro-angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors is postulated to play a causal role in pre-eclampsia (PE). We have described an inbred mouse strain, BPH/5, which spontaneously develops a PE-like syndrome including late-gestational hypertension, proteinuria, and poor feto-placental outcomes. Here we tested the hypothesis that an angiogenic imbalance during pregnancy in BPH/5 mice leads to the development of PE-like phenotypes in this model. Similar to clinical findings, plasma from pregnant BPH/5 showed reduced levels of free vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and placental growth factor (PGF) compared to C57BL/6 controls. This was paralleled by a marked decrease in VEGF protein and Pgf mRNA in BPH/5 placentae. Surprisingly, antagonism by the soluble form of the FLT1 receptor (sFLT1) did not appear to be the cause of this reduction, as sFLT1 levels were unchanged or even reduced in BPH/5 compared to controls. Adenoviral-mediated delivery of VEGF121 (Ad-VEGF) via tail vein at e7.5 normalized both the plasma free VEGF levels in BPH/5 and restored the in vitro angiogenic capacity of serum from these mice. Ad-VEGF also reduced the incidence of fetal resorptions and prevented the late-gestational spike in blood pressure and proteinuria observed in BPH/5. These data underscore the importance of dysregulation of angiogenic factors in the pathogenesis of PE, and suggest the potential utility of early pro-angiogenic therapies in treating this disease.

Keywords: hypertension, proteinuria, PGF, sFLT1, angiogenesis, placenta

Introduction

Pre-eclampsia (PE) is a pregnancy-specific syndrome defined by sudden onset of hypertension and proteinuria after 20 weeks gestation. A multi-system disorder that impacts both mother and fetus, PE is a major public health problem. Worldwide, PE affects 5-8% of pregnancies and is the leading cause of maternal and fetal deaths.1, 2 In developing countries, the incidence of PE is even higher.3 Despite its common occurrence and serious consequences, treatment of PE has not changed over the last century. Even today, the only known effective means to avoid progression to eclampsia is delivery of the fetus and placenta. As such, PE accounts for up to 20% of preterm births worldwide.3

The etiology of PE remains unclear, however there is growing evidence that an imbalance in several members of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) family and its receptors is linked to the clinical syndrome.1, 4 VEGF-A (VEGF), critical to angiogenesis and vasculogenesis required for placentation, is present in numerous isoforms.5 VEGF121, the predominant isoform, lacks a membrane-bound motif, making it freely diffusible and therefore having the greatest therapeutic potential.5 The closely related placental growth factor (PGF) shares 42% sequence homology to VEGF and shares a common receptor, VEGFR-1 (i.e. Fms-like tyrosine kinase 1, FLT1).6, 7 Many women who develop PE show decreases in circulating free VEGF and PGF starting in early- to mid-gestation.1, 2, 8 In addition, high levels of the soluble form of the FLT1 receptor (sFLT1) and soluble endoglin (sENG), both anti-angiogenic factors, are also reported in PE patients at various times during pregnancy.9-11 On the other hand, increased serum sFLT1 levels are not always observed in women with PE,12 and a recent study showed that not only were elevated sFLT1 levels at 11-14 weeks not predictive of PE in women, but were in fact associated with reduced risk for delivery of a small-for-gestational-age baby.13

Despite discrepancies in clinical findings, significant progress in basic research has been made to support the hypothesis that an imbalance between pro-angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors is involved in the pathogenesis of PE. Maynard et al. found that adenoviral-mediated increases in circulating sFLT1 levels in normal pregnant rats induced a PE-like syndrome.9 A similar study in mice confirmed that exogenous delivery of sFLT1 during pregnancy can induce late-gestational hypertension.14 To determine if the effects of exogenous sFLT1 could be counterbalanced by increasing pro-angiogenic factors, Li et al. used repeated subcutaneous injections of VEGF121 and found that this attenuated PE symptoms in pregnant rats previously made pre-eclamptic by an adenovirus encoding sFLT1.15 A similar strategy was adopted by Gilbert et al. in the context of a rat model in which the uteroplacental circulation is disrupted at mid-gestation, and increased circulating levels of sFLT1 late in pregnancy were observed.16 These studies provide important proof-of-concept that an angiogenic imbalance can induce some aspects of PE, however the experimental design is somewhat predictive of the outcome. Testing whether there is endogenous angiogenic imbalance in an animal model that spontaneously develops PE is an important next step.

Several years ago we described an inbred murine strain, BPH/5, which spontaneously develops a maternal and feto-placental syndrome that bears striking resemblance to PE.17 The model is characterized by late-gestational hypertension, proteinuria, renal glomerular lesions and endothelial dysfunction.17, 18 In addition to the maternal systemic disorder, BPH/5 also show feto-placental defects reminiscent of human PE, including defective trophoblast invasion of the maternal decidua and diminished remodeling of maternal spiral arteries.19 This translates into dramatic decreases in end-diastolic blood flow in uterine arteries,19 taken clinically to indicate placental vascular insufficiency.20 BPH/5 also exhibit impaired endothelial cell branching and development of the fetal labyrinth, which is associated with fetal growth restriction, intrauterine fetal demise and small litters of low birth-weight pups.17-19

Based on our findings of feto-placental defects indicative of poor angiogenesis/vasculogenesis in the BPH/5 model, together with clinical evidence of an angiogenic imbalance in women with PE, we hypothesized that BPH/5 would exhibit altered levels of endogenous pro- and anti-angiogenic factors during pregnancy, and this would translate into a maternal and feto-placental syndrome that resembles human PE. Here we demonstrate that an angiogenic imbalance is present in BPH/5 mice during early-to-mid gestation, and this is due to decreased levels of pro-angiogenic VEGF and PGF, but not increased levels of anti-angiogenic sFLT1. Adenovirus-mediated delivery of VEGF121 early in pregnancy (e7.5) in BPH/5 normalized VEGF levels, reduced fetal resorptions and prevented spontaneous development of late-gestational hypertension and proteinuria in this model. These data underscore the importance of angiogenic imbalance in the pathogenesis of PE, and further suggest the potential utility of early pro-angiogenic therapies in treating this disease.

Methods

An expanded Methods section is available in the online data supplement at http://hypertension.ahajournals.org.

Animals and husbandry

Experiments were performed in 8-12 wk old BPH/5 and control C57Bl/6 (C57) mice obtained from in-house colonies.17 Mice underwent strain-matched mating and presence of vaginal plug was defined as e0.5.17 Gestational stages were defined as early: e9.5-12.5; middle: e13.5-15.5; late: e18.5-19.5. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at The University of Iowa and Cornell University.

Adenoviruses

Adenoviral vectors encoding VEGF121 (Ad-VEGF) or a control gene β-galactosidase (Ad-LacZ) were prepared by the University of Iowa Gene Transfer Vector Core. Viruses were injected via tail vein on e7.5 (100 μl, 109 PFUs).

ELISA assays

Blood was collected from non-pregnant (NP), early, and mid-gestation BPH/5 and C57 females via cardiac puncture. ELISA assays for VEGF, PGF, sFLT1 and sENG were performed according to manufacturer's instructions.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Placental tissue was collected at various gestational time-points, total RNA was harvested and cDNA generated. Templates were subjected in triplicate to real-time PCR using Sybr Green and target-specific primers for Vegf, Pgf and sFlt-1.

Western analysis

VEGF protein was measured by Western blot performed on placental lysates subjected to SDS-PAGE. Samples were incubated with goat polyclonal anti-VEGF (1:500, Sigma-Aldrich) followed by donkey anti-goat IgG peroxidase (1:10, Santa Cruz) and subjected to chemiluminescence.

In Vitro Angiogenesis Assay

The in vitro angiogenesis assay was performed in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) utilizing a kit (Trevigen) according to manufacturer's instructions. Total tube lengths per well were measured using Image J software. Data were normalized to the FBS control.

Radiotelemetric measurement of blood pressure

NP females were implanted with radiotelemeters and allowed 1 wk recovery as described.21 Blood pressure (BP) was recorded for 3 days prior to strain-matched mating, and then continuously following vaginal plug detection (e0.5) and through the post-partum period.17, 18 Titer-matched Ad-VEGF or Ad-LacZ was injected via tail vein on e7.5.

Urine protein analysis

Urine samples from mice treated with viruses on e7.5 were collected at various gestational time-points and frozen at -20°C until Bradford analysis as described.17, 18

Analysis of pregnancy outcomes

Mice treated with viruses on e7.5 were euthanized at mid-gestation, uterine horns exposed, and fetuses counted. Fetal resorptions were identified by necrotic/hemorrhagic appearance.17, 18 In three additional cohorts of virus-treated females, placental weights, fetal weights and numbers of live pups born were recorded.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls test was performed for all data sets. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Angiogenic imbalance in pregnant BPH/5 is due to decreased pro-angiogenic factors

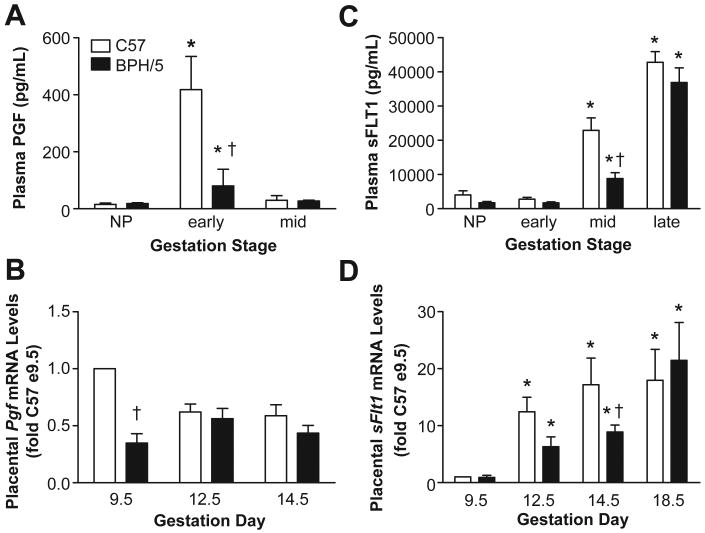

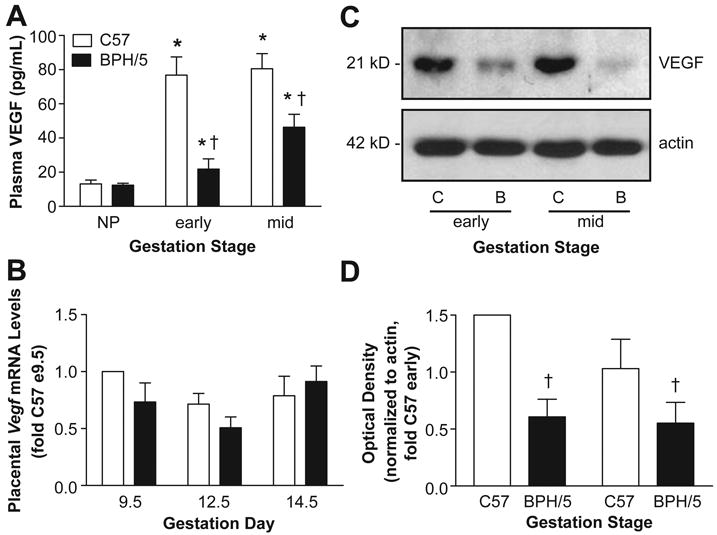

Free VEGF levels were compared in BPH/5 and C57 plasma from early- and mid-gestation. We focused on these time-points since clinical data points to early- or mid-gestational decreases in VEGF in women with PE.1, 8 There was a marked increase in circulating free VEGF in C57 controls at both early- and mid-gestation compared to NP levels (Fig 1A). BPH/5 also showed pregnancy-induced increases in plasma VEGF, however this was significantly blunted at both time-points compared to C57 (Fig 1A). Since the placenta is an important source of angiogenic factors during pregnancy,22 we next compared Vegf mRNA levels in placental samples from C57 and BPH/5 at three time-points. Summary data presented in Fig 1B shows no differences in Vegf transcript levels between C57 and BPH/5 at any of the gestational time-points examined. Since emerging evidence suggests that VEGF expression is regulated via miRNA-mediated repression of Vegf mRNA translation,23 we next measured VEGF protein in placentae using Western analysis. As seen in Fig 1C and D, VEGF protein expression was significantly decreased in BPH/5 placentae at both early- and mid-gestational time-points compared to C57 controls, consistent with the plasma VEGF data.

Figure 1. Circulating and placental VEGF levels are decreased in BPH/5.

A) Summary of circulating free VEGF as determined by ELISA in non-pregnant (NP) and at early and mid-gestation C57 and BPH/5 (n=4-6 per group). B) Summary of real-time qPCR analysis of placental Vegf mRNA levels at different days of gestation (n=5 per group). Data are expressed relative to C57 at e9.5 C) Representative Western blot of VEGF protein levels in placenta samples from C57 (C) and BPH/5 (B) at early and mid-gestation. β-actin served as loading control. D) Summary of Western blot quantification (n=3 per group at each time-point) normalized to actin and expressed relative to C57 early. *p<0.05 vs NP in matched strain; †p<0.05 vs. time-matched C57.

We next compared circulating free PGF in BPH/5 and C57 at early- and mid-gestation since decreased levels of this growth factor at these time-points is associated with PE in women.8 There was a marked early increase in plasma PGF levels in C57, and this returned to NP levels by mid-gestation (Fig 2A). Although BPH/5 showed a significant elevation in free PGF levels at early gestation compared to NP levels, this pregnancy-induced PGF increase was significantly reduced compared to C57 controls (Fig 2A). Since this suggested that BPH/5 placentae produce only modest levels of PGF, we next examined Pgf transcript levels in this tissue using real-time PCR. As shown in Fig 2B, placental Pgf mRNA was reduced in BPH/5 compared to gestation-matched controls at e9.5 but not at other time-points, reflecting the plasma PGF data.

Figure 2. Pro-angiogenic PGF is downregulated, whereas anti-angiogenic sFLT1 is unchanged or even decreased in BPH/5.

A) Summary of free plasma PGF levels as determined by ELISA in non-pregnant (NP) and at different gestational stages of C57 and BPH/5 (n=4-6 per group). B) Summary of Pgf mRNA expression from placental tissue at different gestational days (n=5 per group). Data are expressed relative to C57 at e9.5. C) Summary of circulating sFLT1 levels as determined by ELISA in NP and at different gestational stages of C57 and BPH/5 (n=4-6 per group). D) Summary of real-time qPCR analysis of sFlt1 from placental tissue of C57 and BPH/5 at different gestational days (n=5 per group). *p<0.05 vs NP in matched strain; †p<0.05 vs. time-matched C57.

Since a decrease in VEGF and PGF levels can be accompanied by an elevation in sFLT1 levels in women with PE,1, 9 next we compared the sFLT1 profile in BPH/5 and C57 at early-, mid- and late-gestation. Circulating sFLT1 levels were increased at mid- and late-gestation in both strains relative to NP levels, however the increases in BPH/5 were either not different (late) or even decreased (mid) relative to C57 (Fig 2C). Since the placenta is the major source of sFLT1 during pregnancy,24 we further analyzed placental sFlt1 mRNA. Data in Fig 2D show that placental expression of sFlt1 increased throughout pregnancy in C57 starting at e12.5, and although the temporal profile in BPH/5 mirrors that of C57, mRNA levels were either not altered or even decreased (e14.5) in BPH/5. Finally, since sENG has emerged clinically as a potentially important anti-angiogenic factor in PE,11 plasma sENG levels were compared in BPH/5 and C57 at early- and mid-gestation. As shown in Figure S1, sENG was modestly elevated in BPH/5 at e9.5, but not at the other time-points examined.

Adenoviral delivery of VEGF121 restores circulating free VEGF levels in BPH/5 and rescues the angiogenic potential of serum from pregnant BPH/5

Based on our findings of decreased pro-angiogenic factors in BPH/5, along with the promise of VEGF121 as a therapeutic agent,5, 15, 16 next we determined whether administration of an adenovirus encoding VEGF121 (Ad-VEGF) early in pregnancy in BPH/5 would normalize circulating free VEGF levels. We utilized an adenovirus rather than repeated daily injections of recombinant VEGF12115, 16 in order to effect stable, long-term circulating levels of VEGF121.25 As shown in Figure S2, tail vein injection of Ad-VEGF in NP C57 and BPH/5 females increased plasma VEGF levels more than 20-fold in both strains. Further, Ad-VEGF injected at e7.5 increased circulating VEGF in BPH/5 to levels that were comparable to gestation-matched C57 controls at both early- and mid-gestation (Fig S2). Free VEGF levels of Ad-LacZ-treated mice of both strains were similar to those without viral treatments (Fig 1A), confirming that the viral vector itself had no effect on circulating free VEGF levels.

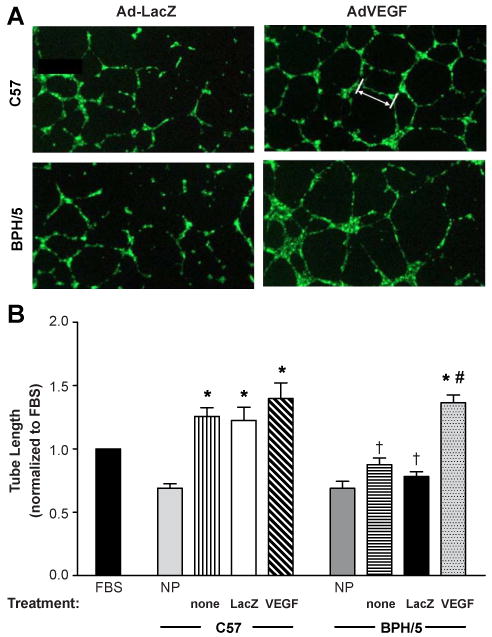

To confirm that the Ad-VEGF-induced elevation in circulating free VEGF leads to functionally active VEGF, we performed a well established in vitro angiogenesis assay in HUVEC cells9 using serum collected from NP or pregnant C57 and BPH/5 mice (e12.5) that had been treated with Ad-LacZ or Ad-VEGF (or no treatment) on e7.5. As seen in representative images and summary data in Fig 3, endothelial tube formation was significantly decreased with e12.5 serum from BPH/5 that had received no viral treatment or had been injected with the Ad-LacZ vector. Ad-VEGF treatment significantly enhanced tube formation elicited by BPH/5 serum compared to that of Ad-LacZ-treated controls, such that there were no differences in tube formation between serum of these mice and C57 controls (all treatments, Fig 3). These results demonstrate that there was functional reconstitution of the angiogenic potential of serum from BPH/5 by systemic Ad-VEGF treatment.

Figure 3. Ad-VEGF therapy rescues the angiogenic potential of BPH/5 serum as measured in an endothelial tube formation assay.

A) Representative images of individual wells of HUVEC cells treated with serum collected from e12.5 C57 and BPH/5 that had undergone tail vein injections of Ad-LacZ or Ad-VEGF on e7.5. White bar (upper right) indicates a representative measurement of tube length. B) Summary of tube lengths normalized to 5% FBS in cells treated with serum from non-pregnant (NP) mice or from e12.5 C57 and BPH/5 mice given no treatment (none) or administered Ad-LacZ or Ad-VEGF on e7.5. NP: n=8 per strain; no treatment and Ad-LacZ: n=5-8 per group and strain; Ad-VEGF: n=5-12 per group and strain. *p<0.05 vs NP matched strain; † p<0.05 vs. C57 in matched treatment; # p<0.05 vs BPH/5 none or Ad-LacZ.

Ad-VEGF therapy early in pregnancy prevents the hallmark maternal PE symptoms and ameliorates fetal resorptions in BPH/5 mice

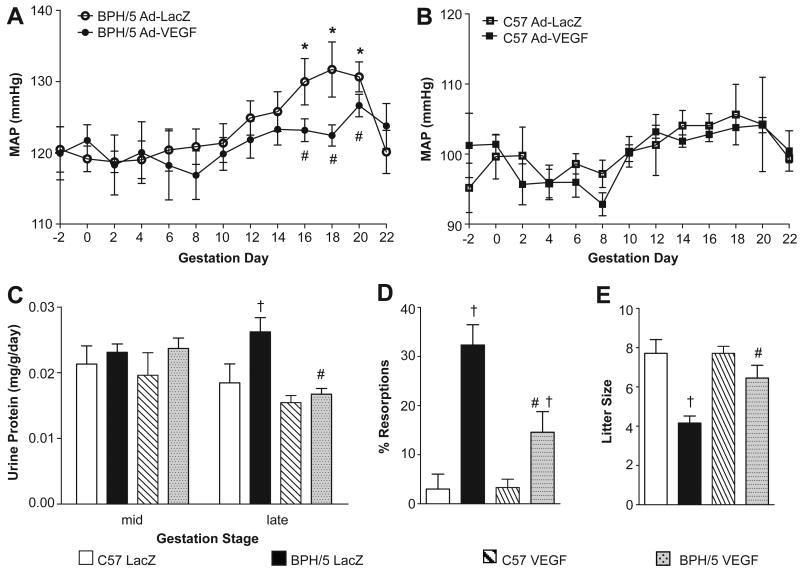

Next we tested the hypothesis that Ad-VEGF administered early in pregnancy in BPH/5 would ameliorate late-gestational hypertension and proteinuria in this model. NP female BPH/5 and C57 mice were implanted with radiotelemeters for continuous measurement of BP before, during and after pregnancy.17, 18 After 1 week recovery, baseline BP was recorded for 3 days before timed strain-matched matings and the start of continuous BP measurements. On e7.5, BPH/5 and C57 mice underwent tail vein injections of Ad-VEGF or Ad-LacZ as above. As seen in Fig 4A and B, baseline mean arterial pressure (MAP) was significantly elevated in Ad-LacZ-treated BPH/5 compared to treatment-matched C57 (120±3 vs. 95±4 mmHg, p<0.05), consistent with our earlier reports that BPH/5 have mildly elevated BP before pregnancy.17, 18 Importantly, neither viral vector altered baseline MAP in either strain (Fig 4A,B). However, pregnancy caused a late-gestational rise in MAP over baseline (days 16-20) in Ad-LacZ-treated BPH/5 mice, which is characteristic of this strain,17, 18 and this was prevented by Ad-VEGF therapy (Fig 4A). Notably, MAP returned to baseline following delivery in Ad-LacZ-treated BPH/5 mice, consistent with what we have shown previously17, 18 and with what occurs in women with PE.26 MAP in C57 controls remained steady throughout pregnancy, and was unaffected by either viral vector (Fig 4B).

Figure 4. Adenoviral-mediated delivery of VEGF121 early in pregnancy prevents the hallmark maternal symptoms and rescues fetal demise in BPH/5.

Summary of radiotelemetric measurements of mean arterial pressure (MAP) before, during and after pregnancy in BPH/5 (panel A) and C57 (panel B) mice. Ad-VEGF or Ad-LacZ were injected by tail vein on e7.5; n=6-8 for each strain and treatment. C) Summary of urinary protein levels at mid- and late-gestation in BPH/5 and C57 mice that had undergone virus injections on e7.5; n=6-12 per group at each time-point. D) Summary of incidence of fetal resorptions at e14.5 in C57 and BPH/5 mice that had undergone virus injections on e7.5; n=8-11 per group. E) Term litter sizes in each of the strains and virus treatment groups; n=11-18 litters per group. *p<0.05 vs baseline in matched strain; #p<0.05 vs BPH/5 Ad-LacZ; †p<0.05 vs C57 in matched treatment.

In a separate cohort of C57 and BPH/5 mice that had undergone Ad-VEGF or Ad-LacZ injections at e7.5, 24-hr urine samples were collected at mid- and late-gestation and subjected to protein analysis. Proteinuria is detected only during late-gestation in BPH/5 mice.17, 18 These data were confirmed here, wherein urinary protein levels were significantly elevated in Ad-LacZ-treated BPH/5 compared to treatment-matched C57 controls at late- but not mid-gestation (Fig 4C). Furthermore, similar to its effects on BP, Ad-VEGF administered early in pregnancy prevented development of proteinuria during late-gestation in BPH/5 (Fig 4C). Ad-VEGF did not alter urinary protein levels in C57 mice at either gestational time (Fig 4C).

To determine whether decreased VEGF production during early pregnancy is an important contributor to feto-placental defects observed in BPH/5 mice,17, 19 we examined several feto-placental outcomes in BPH/5 and C57 mice treated with Ad-VEGF or Ad-LacZ on e7.5 as above. Data presented in Fig 4D show that a third of feto-placental units in BPH/5 mice treated with the control vector were resorbed, whereas resorptions in Ad-LacZ-treated C57 mice were extremely rare. These results are consistent with our earlier report of fetal resorption incidence in BPH/5,17 and confirm that systemic delivery of adenovirus itself does not elicit resorptions. Importantly, Ad-VEGF reduced this fetal demise observed in BPH/5 by ∼50% (Fig 4D), which resulted in a significant increase in term litter size compared to Ad-LacZ-treated mice (Fig 4E). On the other hand, VEGF therapy did not restore mid- or late-gestational placental or fetal weights in BPH/5 (Table 1). It should be noted that in C57 mice, Ad-VEGF treatment had no significant effect on feto-placental outcomes except a small reduction in fetal weight at e14.5 (Fig 4 and Table 1).

Table 1. Placental and fetal weights (mg).

| Gestation day and Sample | Treatment | Strain | Mean ± SEM | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| e14.5 Placental Weight (mg) | Ad-LacZ | C57 | 103.1±3.9 | 26 |

| BPH/5 | 81.7±5.1 * | 40 | ||

| Ad-VEGF | C57 | 109.4±4.2 | 19 | |

| BPH/5 | 93.4±3.8 * | 13 | ||

| e14.5 Fetal Weight (mg) | Ad-LacZ | C57 | 293.4±12.9 | 20 |

| BPH/5 | 196.4±6.8 * | 29 | ||

| Ad-VEGF | C57 | 236.9±5.4 † | 28 | |

| BPH/5 | 174.1±8.6 * | 15 | ||

| e18.5 Placental Weight (mg) | Ad-LacZ | C57 | 91.3±3.1 | 35 |

| BPH/5 | 105.3±4.1 * | 26 | ||

| Ad-VEGF | C57 | 90.8±3.1 | 42 | |

| BPH/5 | 99.4±3.2 | 32 | ||

| e18.5 Fetal Weight (mg) | Ad-LacZ | C57 | 1168±19.0 | 35 |

| BPH/5 | 1053±40.5 * | 23 | ||

| Ad-VEGF | C57 | 1193±18.5 | 44 | |

| BPH/5 | 1022±22.3 * | 29 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of n given in table for each treatment and strain.

p<0.05 vs. C57 in matched treatment,

p<0.05 vs C57 Ad-LacZ.

Discussion

The angiogenic imbalance theory of PE, first posited by Karumanchi and colleagues, has gained significant traction over the years. Their landmark study in 2003 showed that the VEGF and PGF antagonist sFLT1 is upregulated in placentae of PE patients, and this is associated with increased circulating levels of sFLT1 and decreased free plasma VEGF and PGF.9 A number of follow-up clinical studies supported these findings,1, 10, 27 and an era began of determining whether these factors could be used as biomarkers and/or therapeutic targets in PE.27, 28 However, more recent clinical data13, 29 and retrospective reviews of clinical studies such as that by Widmer et al.30 reveal a much more complex picture. In parallel to the clinical studies, basic research in animal models has yielded important proof-of-concept support for this hypothesis. 9, 14, 15 However, the experiments have involved exogenous delivery or experimental induction of sFLT1 and subsequent injections of VEGF121 to ameliorate sFLT1-mediated responses, which complicates interpretation about the endogenous role of these factors in PE. We employed an animal model that spontaneously develops a PE-like syndrome to rigorously test the angiogenic imbalance hypothesis in the laboratory.

First, we found that the increase in plasma free VEGF levels that occurs normally during early- and mid-gestation in murine (C57) pregnancies is significantly attenuated in BPH/5. This appears to be due at least in part to decreased translation of VEGF mRNA in the placenta. The decreased free VEGF levels observed in BPH/5 mice is consistent with human disease data,9 however our finding of diminished placental VEGF protein is in contrast with some reports in PE patients in which VEGF protein and total VEGF circulating levels may actually be higher than in normal pregnancies (but this is compromised by excess sFLT1).31 Second, our results show that the normal pregnancy-induced increase in circulating free PGF in C57 is limited to early gestation, which mirrors the temporal expression pattern of this growth factor in murine placenta observed in this study and others.32 Placental expression and plasma free PGF are also markedly blunted in BPH/5 pregnancies. Third, unlike the increased expression and circulating levels of sFLT1 that have been suggested as a causative factor in PE in women,1, 9, 10 this anti-angiogenic factor is either unchanged or even decreased in BPH/5 placentae and plasma relative to controls. This suggests that while there is marked angiogenic imbalance in the BPH/5 model, it may be due to decreased production of pro-angiogenic VEGF and PGF independent of sFLT1-mediated sequestration of these factors. However, it should be noted that sFLT1 is now known to have at least 4 isoforms, and the isoform that is most dominantly expressed in human PE placentae is not expressed in mice.33,34 Fourth, sENG is modestly elevated transiently at early gestation in BPH/5, suggesting it is not a major contributor to the PE-like syndrome in BPH/5. Finally, we show that decreased expression of VEGF is functionally linked to the development of fetal demise and the maternal PE-like syndrome in BPH/5 mice since early (e7.5) systemic delivery of Ad-VEGF normalized circulating free VEGF, rescued the angiogenic capacity of serum from pregnant BPH/5, decreased fetal resportions and prevented the hallmark late-gestational hypertension and proteinuria observed in this model.

Although it is widely accepted that the placenta is the major source of angiogenic factors during pregnancy,19, 22, 32 it has been difficult to directly link changes observed in plasma from PE patients to dysregulation of these genes in the placenta due to lack of availability of placental tissue from PE patients at early time points. However, a few studies have demonstrated that cytotrophoblasts from preeclamptic patients show lower staining of VEGF and its receptors, suggesting dysregulation of angiogenic genes in the placenta.31, 35 Our data highlight the possibility of post-transcriptional regulation of VEGF in the placenta because while there is a marked decrease in VEGF protein levels in BPH/5 placentae, mRNA levels of VEGF are not significantly changed at any time-point compared to controls. Several mechanisms for post-transcriptional regulation of VEGF in other tissues have been postulated, including down-regulation by microRNAs and translational regulation by cMyc.23 In addition, hypoxia is known to stabilize Vegf mRNA,36 and a stress-responsive ‘switch’ in the 3′ UTR of Vegf has been shown to regulate its expression during hypoxia.37 This is interesting since it has been postulated that PE is associated with premature breach of the trophoblast shell in early placental development and a subsequent burst of hyperoxia in the developing placental tissue.38 Although decreased PGF in BPH/5 appears to be due to decreased placental transcription during early gestation, similar to VEGF, PGF regulation by miRNA-mediated repression of translation cannot be ruled out. Our unpublished data shows that in early-gestational BPH/5 placentae, there is marked upregulation of several microRNAs that are known to bind and repress translation of both VEGF and PGF mRNA (Zhou, Guruju, Woods, Sharma and Davisson, unpublished results).

The mechanisms by which decreased circulating free VEGF or PGF during early and mid-gestation result in the multi-system dysfunction observed in PE are not yet fully understood. Given their importance in angiogenesis and vascular remodeling during fetoplacental development, as well as in maintaining maternal cardiovascular and renal function, there are several possibilities. First, a decrease in placental synthesis and secretion of VEGF and PGF by villous cytotrophoblasts, fetal macrophages and fetal fibroblasts may lead to decreases in vasculogenesis and angiogenesis, causing poor placentation.22, 39 Early defects in placentation due to decreased production of these pro-angiogenic factors could cause the so-called “Stage 1” of the disease, characterized by reduced feto-placental perfusion, placental oxidative stress and inflammation.39, 40 Indeed, it is interesting to speculate that Ad-VEGF, by ameliorating poor placentation in the BPH/5 model, leads to reduced fetal resorptions as reported in Fig 4D, and that this may be the critical upstream event in Ad-VEGF's beneficial effects on maternal symptoms in this model. It should also be noted that another splice variant of the gene encoding a solube form of the VEGF receptor-2 has recently been identified and shown to inhibit angiogenesis.41 It will be intriguing to determine if this isoform is altered in BPH/5 placentae.

In addition to the placenta, angiogenic factors play an important role in various other organ systems. For example, VEGF expression is critical to maintaining the fenestrated and sinusoidal endothelium of the kidney and choroid plexus of the brain and liver, three distinct areas that are affected in PE patients.1, 42 Podocytes, renal epithelial cells that form the outermost glomerular filtration barrier, synthesize large amounts of VEGF, which is required for development and function of the glomerular filtration barrier.42, 43 Decreased circulating or local podocyte levels of VEGF could lead to damage of glomerular endothelium and increased protein secretion into the urine.1, 42 VEGF is also known to regulate vascular permeability, and dysregulation of this process can result in edema, another distinct feature of PE.1 Furthermore, evidence from anti-angiogenic cancer clinical trials using anti-VEGF antibodies shows that VEGF antagonism results in hypertension, glomerular endotheliosis and proteinuria,44 again reinforcing the potential role of decreased VEGF in the development of gestational hypertension and proteinuria. Given the powerful effects of early Ad-VEGF treatment on BPH/5 fetal outcomes and maternal endpoints in this study, it will be important to determine the site(s) and mechanisms by which increased levels of this pro-angiogenic factor mediates its effects.

Emerging evidence suggests that decreased levels of circulating VEGF may also contribute to oxidative stress-induced endothelial dysfunction. Recent work from Granger and colleagues has shown that exogenous delivery of recombinant sFLT1 into pregnant rats results in reduced plasma free VEGF levels, increased vascular oxidative stress, decreased NO-dependent vasorelaxation and increased blood pressure.45 Previous work from our laboratory has shown that increased reactive oxygen species scavenging by Tempol starting before and continuing throughout pregnancy ameliorates fetoplacental defects and development of PE symptoms in BPH/5 model.18 These results, along with our current findings of decreased placental and plasma free VEGF in BPH/5 and our previous data showing that BPH/5 exhibit late-gestational endothelial dysfunction17 suggest that dysregulation of VEGF production in this model may lead to maternal oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction. Certainly many previous studies have implicated both increased oxidative stress and angiogenic imbalance in the development of PE, however the pathogenic mechanisms have mostly been considered in parallel.39, 40, 46 The studies discussed above suggest a possible connection between these two pathways.

Perspectives

We have shown that an angiogenic imbalance in BPH/5 mice precedes the onset of maternal PE-like symptoms in this model, and this imbalance is likely due to decreased placental synthesis and circulation of VEGF and PGF independent of increased antagonism by sFLT1. Furthermore, our studies suggest a causal link between decreased VEGF levels and the development of feto-placental defects and maternal PE-like symptoms since early viral delivery of VEGF121 was sufficient to reduce fetal resorptions and prevent late-gestational hypertension and proteinuria in this model. Since fetal loss occurs in advance of hypertension and proteinuria in this model, it is interesting to speculate that Ad-VEGF's beneficial effects on fetal status contributed to amelioration of the maternal syndrome in this study. We believe the BPH/5 model will provide a unique opportunity to now examine the precise molecular underpinnings of changes in the angiogenic profile in the context of PE.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Gene Therapy Vector Core at The University of Iowa for preparation of adenoviral vectors.

Funding Sources: This work was supported by a grant from The Carver Foundation (The University of Iowa) to RLD. RLD is an established investigator of the American Heart Association (0540114N). AKW is funded by a predoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association (09PRE2120035) and the Center for Vertebrate Genomics at Cornell University. DSH was funded by a predoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association (0510021Z) and a Women's Health Dissertation Fellowship from the Woodrow Wilson Fellowship Foundation. CJW was funded by the University of Iowa Cardiovascular Center Institutional Postdoctoral Training Grant (NIH T32 HL07121-30).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Disclosure: none

References

- 1.Maynard S, Epstein FH, Karumanchi SA. Preeclampsia and angiogenic imbalance. Annu Rev Med. 2008;59:61–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.59.110106.214058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts JM, Pearson G, Cutler J, Lindheimer M, NHLBI Working Group on Research on Hypertension During Pregnancy Summary of the NHLBI working group on research on hypertension during pregnancy. Hypertension. 2003;41:437–445. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000054981.03589.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duley L. The global impact of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. Semin Perinatol. 2009;33:130–137. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Myatt L, Webster RP. Vascular biology of preeclampsia. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:375–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor: Basic science and clinical progress. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:581–611. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Falco S, Gigante B, Persico MG. Structure and function of placental growth factor. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2002;12:241–246. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(02)00168-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shibuya M. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 (VEGFR-1/Flt-1): A dual regulator for angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2006;9:225–230. doi: 10.1007/s10456-006-9055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torry DS, Wang HS, Wang TH, Caudle MR, Torry RJ. Preeclampsia is associated with reduced serum levels of placenta growth factor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:1539–1544. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maynard SE, Min JY, Merchan J, Lim KH, Li J, Mondal S, Libermann TA, Morgan JP, Sellke FW, Stillman IE, Epstein FH, Sukhatme VP, Karumanchi SA. Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:649–658. doi: 10.1172/JCI17189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hertig A, Berkane N, Lefevre G, Toumi K, Marti HP, Capeau J, Uzan S, Rondeau E. Maternal serum sFlt1 concentration is an early and reliable predictive marker of preeclampsia. Clin Chem. 2004;50:1702–1703. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.036715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Venkatesha S, Toporsian M, Lam C, Hanai J, Mammoto T, Kim YM, Bdolah Y, Lim KH, Yuan HT, Libermann TA, Stillman IE, Roberts D, D'Amore PA, Epstein FH, Sellke FW, Romero R, Sukhatme VP, Letarte M, Karumanchi SA. Soluble endoglin contributes to the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Nat Med. 2006;12:642–649. doi: 10.1038/nm1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Powers RW, Roberts JM, Cooper KM, Gallaher MJ, Frank MP, Harger GF, Ness RB. Maternal serum soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 concentrations are not increased in early pregnancy and decrease more slowly postpartum in women who develop preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:185–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith GC, Crossley JA, Aitken DA, Jenkins N, Lyall F, Cameron AD, Connor JM, Dobbie R. Circulating angiogenic factors in early pregnancy and the risk of preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction, spontaneous preterm birth, and stillbirth. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:1316–1324. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000265804.09161.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu F, Longo M, Tamayo E, Maner W, Al-Hendy A, Anderson GD, Hankins GD, Saade GR. The effect of over-expression of sFlt-1 on blood pressure and the occurrence of other manifestations of preeclampsia in unrestrained conscious pregnant mice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:396.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.12.024. discussion 396.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Z, Zhang Y, Ying Ma J, Kapoun AM, Shao Q, Kerr I, Lam A, O'Young G, Sannajust F, Stathis P, Schreiner G, Karumanchi SA, Protter AA, Pollitt NS. Recombinant vascular endothelial growth factor 121 attenuates hypertension and improves kidney damage in a rat model of preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2007;50:686–692. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.092098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilbert JS, Verzwyvelt J, Colson D, Arany M, Karumanchi SA, Granger JP. Recombinant vascular endothelial growth factor 121 infusion lowers blood pressure and improves renal function in rats with placental ischemia-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2010;55:380–385. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.141937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davisson RL, Hoffmann DS, Butz GM, Aldape G, Schlager G, Merrill DC, Sethi S, Weiss RM, Bates JN. Discovery of a spontaneous genetic mouse model of preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2002;39:337–342. doi: 10.1161/hy02t2.102904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffmann DS, Weydert CJ, Lazartigues E, Kutschke WJ, Kienzle MF, Leach JE, Sharma JA, Sharma RV, Davisson RL. Chronic tempol prevents hypertension, proteinuria, and poor feto-placental outcomes in BPH/5 mouse model of preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2008;51:1058–1065. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.107219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dokras A, Hoffmann DS, Eastvold JS, Kienzle MF, Gruman LM, Kirby PA, Weiss RM, Davisson RL. Severe feto-placental abnormalities precede the onset of hypertension and proteinuria in a mouse model of preeclampsia. Biol Reprod. 2006;75:899–907. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.053603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parra M, Rodrigo R, Barja P, Bosco C, Fernandez V, Munoz H, Soto-Chacon E. Screening test for preeclampsia through assessment of uteroplacental blood flow and biochemical markers of oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1486–1491. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.02.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Butz GM, Davisson RL. Chronic blood pressure recording in pregnant mice by radiotelemetry. Physiol Genomics. 2001;5:89–97. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.2001.5.2.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burton GJ, Charnock-Jones DS, Jauniaux E. Regulation of vascular growth and function in the human placenta. Reproduction. 2009;138:895–902. doi: 10.1530/REP-09-0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hua Z, Lv Q, Ye W, Wong CK, Cai G, Gu D, Ji Y, Zhao C, Wang J, Yang BB, Zhang Y. MiRNA-directed regulation of VEGF and other angiogenic factors under hypoxia. PLoS One. 2006;1:e116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clark DE, Smith SK, He Y, Day KA, Licence DR, Corps AN, Lammoglia R, Charnock-Jones DS. A vascular endothelial growth factor antagonist is produced by the human placenta and released into the maternal circulation. Biol Reprod. 1998;59:1540–1548. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod59.6.1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jalkanen J, Leppanen P, Narvanen O, Greaves DR, Yla-Herttuala S. Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of a secreted decoy human macrophage scavenger receptor (SR-AI) in LDL receptor knock-out mice. Atherosclerosis. 2003;169:95–103. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(03)00155-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berks D, Steegers EA, Molas M, Visser W. Resolution of hypertension and proteinuria after preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:1307–1314. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c14e3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levine RJ, Maynard SE, Qian C, Lim KH, England LJ, Yu KF, Schisterman EF, Thadhani R, Sachs BP, Epstein FH, Sibai BM, Sukhatme VP, Karumanchi SA. Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:672–683. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thadhani R, Mutter WP, Wolf M, Levine RJ, Taylor RN, Sukhatme VP, Ecker J, Karumanchi SA. First trimester placental growth factor and soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 and risk for preeclampsia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:770–775. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Savvidou MD, Yu CK, Harland LC, Hingorani AD, Nicolaides KH. Maternal serum concentration of soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 and vascular endothelial growth factor in women with abnormal uterine artery doppler and in those with fetal growth restriction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1668–1673. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Widmer M, Villar J, Benigni A, Conde-Agudelo A, Karumanchi SA, Lindheimer M. Mapping the theories of preeclampsia and the role of angiogenic factors: A systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:168–180. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000249609.04831.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsatsaris V, Goffin F, Munaut C, Brichant JF, Pignon MR, Noel A, Schaaps JP, Cabrol D, Frankenne F, Foidart JM. Overexpression of the soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor in preeclamptic patients: Pathophysiological consequences. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5555–5563. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Achen MG, Gad JM, Stacker SA, Wilks AF. Placenta growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor are co-expressed during early embryonic development. Growth Factors. 1997;15:69–80. doi: 10.3109/08977199709002113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sela S, Itin A, Natanson-Yaron S, Greenfield C, Goldman-Wohl D, Yagel S, Keshet E. A novel human-specific soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1: Cell-type-specific splicing and implications to vascular endothelial growth factor homeostasis and preeclampsia. Circ Res. 2008;102:1566–1574. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.171504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heydarian M, McCaffrey T, Florea L, Yang Z, Ross MM, Zhou W, Maynard SE. Novel splice variants of sFlt1 are upregulated in preeclampsia. Placenta. 2009;30:250–255. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou Y, McMaster M, Woo K, Janatpour M, Perry J, Karpanen T, Alitalo K, Damsky C, Fisher SJ. Vascular endothelial growth factor ligands and receptors that regulate human cytotrophoblast survival are dysregulated in severe preeclampsia and hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets syndrome. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:1405–1423. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62567-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu LX, Lu H, Luo Y, Date T, Belanger AJ, Vincent KA, Akita GY, Goldberg M, Cheng SH, Gregory RJ, Jiang C. Stabilization of vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;291:908–914. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ray PS, Jia J, Yao P, Majumder M, Hatzoglou M, Fox PL. A stress-responsive RNA switch regulates VEGFA expression. Nature. 2009;457:915–919. doi: 10.1038/nature07598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jauniaux E, Watson AL, Hempstock J, Bao YP, Skepper JN, Burton GJ. Onset of maternal arterial blood flow and placental oxidative stress. A possible factor in human early pregnancy failure. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:2111–2122. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64849-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Redman CW, Sargent IL. Placental stress and pre-eclampsia: A revised view. Placenta. 2009;30 A:S38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roberts JM, Hubel CA. The two stage model of preeclampsia: Variations on the theme. Placenta. 2009;30 A:S32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Albuquerque RJ, Hayashi T, Cho WG, Kleinman ME, Dridi S, Takeda A, Baffi JZ, Yamada K, Kaneko H, Green MG, Chappell J, Wilting J, Weich HA, Yamagami S, Amano S, Mizuki N, Alexander JS, Peterson ML, Brekken RA, Hirashima M, Capoor S, Usui T, Ambati BK, Ambati J. Alternatively spliced vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 is an essential endogenous inhibitor of lymphatic vessel growth. Nat Med. 2009;15:1023–1030. doi: 10.1038/nm.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eremina V, Baelde HJ, Quaggin SE. Role of the VEGF--a signaling pathway in the glomerulus: Evidence for crosstalk between components of the glomerular filtration barrier. Nephron Physiol. 2007;106:32–37. doi: 10.1159/000101798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robert B, Zhao X, Abrahamson DR. Coexpression of neuropilin-1, Flk1, and VEGF(164) in developing and mature mouse kidney glomeruli. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2000;279:F275–282. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.279.2.F275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sugimoto H, Hamano Y, Charytan D, Cosgrove D, Kieran M, Sudhakar A, Kalluri R. Neutralization of circulating vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) by anti-VEGF antibodies and soluble VEGF receptor 1 (sFlt-1) induces proteinuria. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:12605–12608. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bridges JP, Gilbert JS, Colson D, Gilbert SA, Dukes MP, Ryan MJ, Granger JP. Oxidative stress contributes to soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 induced vascular dysfunction in pregnant rats. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22:564–568. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2009.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cindrova-Davies T. Gabor than award lecture 2008: Pre-eclampsia - from placental oxidative stress to maternal endothelial dysfunction. Placenta. 2009;30 A:S55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.