Abstract

Periodic outbreaks of pandemic influenza have been a devastating cause of human mortality over the past century. More recently, an avian influenza strain, designated H5N1, has been identified as having the potential to cause a zoogenic pandemic in humans, and a current outbreak of a new H1N1 influenza variant hypothesized to be of swine origin is of considerable concern. In order to facilitate surveillance and the rapid assessment and comparison of vaccination efforts, a high-throughput assay is highly desirable to supplement standard methods, which require high biosafety-level facilities. In this paper, we describe the design, production, and preliminary evaluation of an antigen array incorporating a panel of hemagglutinins as a platform for the detection and rapid quantification of influenza-specific antibodies in human serum by Arrayed Imaging Reflectometry (AIR), a label-free optical biosensor.

Emerging avian H5N1 and swine H1N1 influenza serotypes are currently the subject of major international research endeavors. Past influenza pandemics have proven that in the absence of proper safeguards, new and highly pathogenic strains of influenza can be extremely deadly. With the rise in the global population and the advent of international travel and commerce, the repercussions of a modern pandemic would be devastating [i]. Since its initial isolation in 1997 [ii], there have been a reported 500 cases of H5N1 in humans that have resulted in 296 deaths [iii]. The majority of these reported cases have resulted from avian to human transmission, but isolated cases of human-to-human transmission have been reported as well [iv]. As a precaution, governments are stockpiling drugs in the event that a vaccine is not created, is not efficient, or is not able to be produced in a sufficient, global quantity [v]. Unfortunately, as has been evident with the prescription of broad-spectrum antibiotics [vi], a few cases of drug-resistant H5N1 strains have already been reported [vii]. Moreover, the preventative culling of high-risk poultry populations is a common practice, and has led to the destruction of well over 240 million birds [viii]. The recent global emergence of H1N1 swine influenza, now officially listed by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a pandemic [ix] and anticipated to infect as many as 2 billion people over the next two years, highlights the continued ability of this organism to evolve and impact world events.

Responding to disease threats of this type is a dual-armed problem. First, surveillance of human and animal populations is essential in order to understand the extent of infection, and to monitor the success of containment or treatment efforts. Second, continued vaccine development and assessment of efficacy is essential as viral populations change. In both cases, a high-throughput assay to monitor immune responses is highly desirable to assess the presence of infection or response to a candidate vaccine. In the context of influenza, standard methods require high biosafety level facilities and cannot be readily implemented in a high-throughput fashion. All of these issues separately point to the need for the development of simple, field-deployable surveillance systems of viral exposure and immune status. The availability of such systems would have implications for improving human health, stabilizing global food supplies, upholding the ethical treatment of animals (by limiting culling), and for anticipating future zoogenic serotypes of influenza.

Immunological assays, intended for population or vaccination monitoring, ultimately require an analytical biomarker indicative of infection or resistance. Hemagglutinin (HA) is the influenza antigen responsible for mediating host cell recognition via surface sialic acid receptors [x] and is the main antigenic protein on the surface of the influenza virus [xi]. HA anchored in viral constructs [xii, xiii]. or in recombinant form [xiv, xv, xvi], is the current focus of efforts towards developing effective vaccines. Monitoring an immunologic response to a candidate vaccine typically requires the use of functional assays, such as hemagglutinin inhibition (HAI) and viral microneutralization (MN). As the reference standards to ascertain antibody titers in subject antisera, these tests must be performed in centralized, high biosafety level (BSL-2+ or BSL-3) facilities due to the use of cultures containing proliferative viruses. They provide the principal set of data supporting or refuting the efficacy of a vaccination, but are extremely time- and cost-intensive. HAI and MN assays are also commonly employed as tools for infection surveillance. It is difficult to envision a method for supplanting these assays entirely in the context of vaccine development, as one cannot demonstrate protective immunity without employing live viruses. However, demonstrating the presence of antibodies to specific influenza antigens independent of their protective capability is of considerable importance, and currently both ELISA and Western blot methods are commonly employed for this purpose [xvii]. A rapid and consistent preliminary assay able to be safely performed in the field or in standard BSL-2 laboratories would dramatically simplify surveillance and vaccine development efforts, allowing rapid profiling of samples. Where necessary, the presence of neutralizing antibodies could be subsequently confirmed for strong-responder samples by HAI or MN. Proteome profiling via protein microarrays has proven useful in many studies focused on understanding basic biochemical processes [xviii, xix, xx], but, more germane to the research reported herein, microarrays have also been used to discover antigenic proteins and monitor immunological responses to them [xxi, xxii, xxiii]. Thus, antigen arrays would seem to be ideal for the development of influenza surveillance and immunity screening tools. Unfortunately, most current microarray technologies rely on labeling schemes, and are too unwieldy for field use.

Over the past several years, we have been engaged in the development and characterization of Arrayed Imaging Reflectometry (AIR) [xxiv, xxv]. AIR is an optical biosensor allowing direct observation of target binding-induced perturbation of an antireflective coating on the surface of a silicon substrate. Briefly, the antireflective condition arises when s-polarized light of a specific wavelength and angle is incident upon a thin layer of silicon dioxide, appended with capture molecules, of a particular thickness. The resulting surface is thus highly sensitive to local deviations in the thickness of the interfering film: a film thickening due to specific capture of a target molecule, and the ensuing destruction of the local destructive interference condition, gives rise to signal generation in the form of reflected light. In this manner, multiple probe/target interactions may be rapidly and simultaneously monitored due to the spatial separation in an array without any requirement for secondary antibodies or labeling. As such, AIR appeared to us to be an ideal platform for the development of a rapid influenza immunity screening tool, and we therefore describe here the preparation and evaluation of AIR hemagglutinin isoform arrays for this purpose.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the array, we examined antisera previously obtained from a blinded pool of trial subjects as part of a trial of an inactivated subvirion H5N1 avian influenza vaccine [xxvi]. These antisera were analyzed to determine immunogenic responses, distinguish placebo subjects, and quantify antigen cross reactivity over a panel of HAs. AIR data were then compared to previously acquired ELISA and Western Blot information. We also report the extension of this methodology and the AIR technique to a microarray format.

Results and Discussion

Macroarrays

As a first step towards understanding the potential of AIR for profiling anti-hemagglutinins in serum, we manually arrayed hemagglutinins on AIR chips pre-functionalized with γ-aminopropyl triethoxysilane (APTES) followed by para-phenylene diisothiocyanate. Test chips prepared using 100 μg/ml spotting solutions of A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (H5) failed, presumably due to insufficient accessibility of immunogenic epitopes due to steric crowding. Subsequent tests with 20 μg/ml spotting solutions of the same antigen produced functional chips, and therefore this concentration was employed for all remaining macroarray experiments.

AIR arrays consisting of six HA isoforms and positive (anti-IgG) and negative (anti-fluorescein) controls were prepared manually (shown schematically in Figure 1). Antisera from six different human subjects were examined: five subjects inoculated with various amounts of A/Hong Kong/156/1997(H5N1) on two separate visits, and one subject who had been given placebo injections only. Aliquots of undiluted serum were then analyzed by AIR, using a benchtop imaging apparatus that we have previously described [xxv]. Representative reference and post-exposure images are shown in Figure 2; reflectance changes from all chips are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 1.

Schematic and key of the manually prepared hemagglutinin array. Each hemagglutinin isoform is represented as an abbreviation of the description of the full viral strain; i.e., “H52: Hong Kong/2003” is the hemagglutinin isolated from a human influenza A strain in Hong Kong in 2003, and the subscript denotes that this is the second version of H5 hemagglutinin used in the array.

Figure 2.

Representative AIR images of manually prepared HA macroarrays acquired on a benchtop imaging apparatus. Top: a control chip, exposed to buffer only. Bottom: an experimental chip, exposed to 100% human antiserum. Refer to the array key in Figure 1 for the description of the full hemagglutinin array.

Figure 3.

Quantification of reflectance changes for all hemagglutinin isoforms upon exposure to serum from six clinical subjects. Numbers next to the subject designator refer to the amount of antigen (in micrograms) administered at each of two visits. Refer to the array key in Figure 1 for the full antigen array description. The anti-fluorescein control was set at a value of zero for all chips and is therefore not shown. For clarity, responses to H5 isoforms are shown in summation; individual H5 responses are shown in an expanded Figure in the supplementary information (Figure S1).

Experiments were conducted “blind” with regard to the identity of each sample. Analysis of the data allowed us to hypothesize that sample “A” was the placebo sample, as it yielded the lowest reflectivity values for total H5 reflectance. On revealing the identity of the samples, “A” was indeed found to be the subject receiving placebo inoculations. In general terms, samples “B” through “F” produced higher H5 reflectivity values, which is consistent with the induction of an immune response to injected antigen. Differences between closely related samples such as “B” and “C” were intriguing, and may be attributed to the idiosyncrasies of individual subjects’ immune responses.

When compared to the total amount of antigen inoculated during the two visits, the Pearson correlations of each antigen suggest that H52 (R = 0.98) was the single best biomarker to monitor H5N1 vaccination efficiency for this set of subjects and array geometry. We further compared results from AIR experiments with previously obtained ELISA and western blot data (Table 1), the conventional companions to HAI and MN bioassays. As there was no agreement between ELISA and western blot results (e.g., for subjects “B” and “C”), we will restrict the comparison of AIR to ELISA data, only. Overall ELISA measurements correlated poorly with both inoculation amount and the data generated by AIR (Pearson R-values of 0.37 and 0.36, respectively, the correlation improved to a Pearson R-value of 0.85 if subject “B” was removed from the comparison). A graphical comparison of ELISA and AIR results is provided in Figure S5 (Supplementary Information). Several factors may contribute to differences in analytical results for these assays. As AIR is a label-free technique and ELISA requires a secondary antibody, the secondary antibody itself and/or variable activity of the antibody-conjugated enzyme may change response. Additionally, serum samples were frozen between ELISA assays and AIR analysis, and this may subtly alter sample composition. Further study will be needed on larger cohorts of subjects to assess these differences thoroughly and their impact on the quality of information obtained from the AIR assay.

Table 1.

Tabulated results from enzyme-linked immunosorbant assays (ELISA; measured as an optical density, OD) and western blots (thresholded either as a positive or negative result) performed on antiserum from subjects A – F. Each subject was inoculated on two separate visits with an H5 antigen (expressed in micrograms).

| Subject | Amount (μg) | ELISA OD | Western Blot |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | placebo | 0.235 | negative |

| B | 25/25 | 1.677 | negative |

| C | 25/25 | 1.856 | positive |

| D | 90/10 | 0.652 | negative |

| E | 90/60 | 1.160 | negative |

| F | 90/90 | 1.748 | positive |

Microarrays

Due to the arrayed nature of AIR, a considerable amount of information can be generated from a single aliquot of serum and a single analysis. We demonstrated this concept using a microarray AIR format to examine a second set of serum samples from a subsequent avian influenza vaccination trial [xxvi]. We incorporated a single H5 isoform, (A/Vietnam/1203/2004), into the array in order to broadly study cross-reactivity between hemagglutinins. Examination of microarrays was facilitated by our acquisition of a prototype AIR reader from Adarza BioSystems, Inc.; this device incorporates a proprietary optical system suitable for imaging microarray-sized (ca. 100 micrometer) spots [xxvii]. The microarray panel was composed of H1, H3, H5, H6, and H9 hemagglutinins, and two positive (anti-IgG and anti-IgM) and two negative (human serum albumin (HSA) and anti-fluorescein) controls. HSA was employed as the global assay negative control, because potential nonspecific interactions would be pre-competed in solution-phase rather than at the surface of the chip.

All antisera studied by dilution series were examined in log5 steps; however, the majority of the antisera were studied at a single 1:20 (5%) dilution in order to quantify trends in cross-reactivity. Representative microarray images are shown in Figure 4; a heat map of all data acquired in this manner is shown in Figure 5. The buffer control arrays for antiserum experiments were analyzed to quantify array-to-array reproducibility. The largest reflectance variations between control chips were observed for anti-IgG spots (3.05 ± 7.0 in arbitrary units), while the most reproducible spots were anti-fluorescein (2.66 ± 1.5 in arbitrary units). Reflectance changes in this range were considered negligible relative to changes originating from specifically bound material. A sample of negative control mouse plasma, acquired from mice raised aseptically and without introduction to external pathogens or viruses, was also assayed at a 5% dilution and displayed no reactivity against any HA in the array.

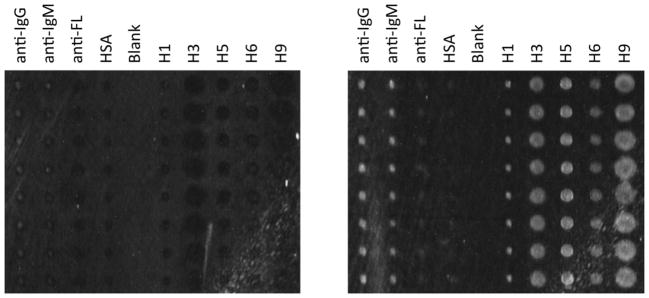

Figure 4.

Representative example of an AIR hemagglutinin microarray for human antiserum experiments. A background image (left) and an experimental image of an array exposed to 5% antiserum (right; subject “K”) are depicted. The array is comprised of eight replicate spots (vertical) of nine different probe molecules. From left to right, the spot identities are anti-IgG, anti-IgM, anti-fluorescein (anti-FL), human serum albumin (HSA), blank column, and hemagglutinin isoforms H1, H3, H5, H6, and H9. Differences in spot size are due to subtle differences in antigen stock solution viscosity, and do not interfere with quantitation.

Figure 5.

A heat map representing reflectance changes quantified from the hemagglutinin microarray panel (H1, H3, H5, H6, and H9) for subject antisera screened at a 5% dilution. Each row describes the identity of the analyzed sample. For example, “buffer” corresponds to the average change of the buffer control chip and “K (7.5 μg)” expresses the subject and amount of subvirion H5N1 vaccine received by that subject. All changes in reflectance were normalized to human serum albumin (see Figure 4) as a negative control.

Subject H had serum aliquoted pre-inoculation in order to quantify innate resistance and determine the direct immunogenic effect of the H5 vaccine. Reflectance changes derived from this subject indicated modest responses to hemagglutinin H3, potentially due to memory immunity derived from a prior influenza infection (exacerbated by our constant exposure to different and evolving seasonal variants of the influenza virus [xxviii]), and slight cross-reactivities to H1 and H9 hemagglutinins (Supplementary Figures 2 and 3). Nevertheless, upon inoculation with H5, subject H gained considerable reactivity to all hemagglutinins in the array, and over a five-fold increase in reflectance change for H5 (Figure 6). The placebo sample was correctly identified from the blinded pool as subject G; the low anti-HA titer for this subject relative to others is clearly observable in Figure 5. A full antiserum titration was then performed in order to monitor the rate of signal depletion against the HAs, and a comparison was made to a subject with moderate HA responses (subject M; Figure 6). Similar to what was observed with the pre-inoculation sample of subject H seen in Figure 5, there is very little basal recognition of H5 and H6 in the non-vaccinated subject. However, antibodies to H1, H3, and H9 hemagglutinins were observed in this pre-vaccine sample. These reflectance changes indicate recognition of the antigen, and may be attributed to a prior (lifetime) exposure to the influenza virus or influenza vaccines or cross-reactivity due to conserved epitopes.

Figure 6.

Comparison of H5 reflectance changes (arbitrary units) for hemagglutinin microarrays exposed to dilutions of placebo (subject G; 0 μg) and experimental (subject M; 45 μg) human antisera. As a further comparison, dilutions from subject H (−/+ 7.5 μg) pre- and post-inoculation are shown.

Cross-Reactivity Between Hemagglutinins

A significant amount of cross-reactivity is observed between different hemagglutinin isoforms upon exposure to antiserum in both macro- and microarrays. While the five isoforms used in our study have an aggregate sequence identity of only 24% and a sequence similarity of 42%, much of this homology is concentrated in the transmembrane domain (Supplementary Figure 4). Availability of this domain on the AIR chip for interaction with serum antibodies is not surprising, given the random orientation of hemagglutinin immobilization (via general amine coupling) and the homotrimeric nature of the hemagglutinin. The antigenicity of the transmembrane domain is well known; for example, two groups have reported raising broadly cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies based on interactions with a transmembrane peptide epitope [xxix, xxx]. Future experiments will test this hypothesis further, potentially using solution-phase, truncated portions of the transmembrane region in an attempt to compete cross-reactive binding off the array.

Comparison of AIR Assay Formats

Data from AIR microarrays show only a limited relationship between vaccine dose and resulting serum titers of anti-hemagglutinins: as expected, H5 demonstrated the best correlation with inoculation amount (R-value = 0.58), while H1 and H3 hemagglutinins correlated negatively with dose. However, these results are consistent with the overall results of the vaccine trial [xxvi], as well as with the generally understood observation that the strength of individual responses to vaccine antigens varies widely. The ability of AIR in both a microarray and macroarray format to clearly distinguish placebo and (in the case of microarray AIR) pre-inoculation antisera from post-vaccine sera is an exceptionally encouraging sign with regard to the ability of the AIR technique to provide useful information regarding vaccine response. This sensitivity, coupled with the antigen multiplexing capability inherent to the platform, makes AIR a powerful and information-rich companion (or precursor) to HAI and MN assays.

Conclusions

A rapid and quantitative primary assay able to be safely performed in BSL-2 laboratories or in the field has the capability to dramatically simplify surveillance and to provide critical data to researchers working towards the development of an avian influenza vaccine. The Arrayed Imaging Reflectometry (AIR) assay was designed to offer all of these advantages, and, through the incorporation of a microarrayed panel of recombinant hemagglutinins, yield a substantial data set with a single sample. As a label-free technique, AIR dispenses with the requirement for secondary antibodies and other reagents, potentially providing a significant cost advantage relative to ELISA or traditional microarrays. Furthermore, the simplicity of the assay potentially makes it suitable for implementation in a field-deployable instrument, a possibility currently under exploration in our laboratory. While more data are required to validate the clinical effectiveness of AIR, results from both macro- and microarray experiments suggest that the data derived from AIR arrays can potentially serve as an adjunct or “pre screen” for hemagglutinin inhibition and viral microneutralization assays, particularly given the lack of correlation from ELISA and western blots. The antiserum sample requirements for this assay are minimal, as a 5 – 10% dilution of serum in buffer supplies ample signal generation, making the hemagglutinin microarray practical for vaccination and viral surveillance applications. Combined with the small footprint (laptop size [xxvii]) and durability of the device, and a similar ability to screen for immune response in non-human plasma (such as from birds; this is demonstrated in Supplementary Figure 5), we can anticipate that this methodology will prove to have broad utility in monitoring and combating influenza globally.

Experimental Section

Hemagglutinins

The H51 (A/Hong Kong/56/1997), H52 (A/Hong Kong/213/2003), H53 (A/Vietnam/1203/2004), H6 (A/Teal/Hong Kong/W312/1997), and H9 (A/Hong Kong/1073/1999) hemagglutinins were obtained through the Biodefense and Emerging Infections Resource Repository (BEIR). H1 (A/New Caledonia/20/1999) and H3 (A/Wyoming/3/2003) were purchased from Protein Sciences Corporation (Meriden, CT). H53 was the only H5 hemagglutinin used in the microarray experiments.

Antisera

Human antisera from subjects of previous H5N1 vaccination trials [xv],[xxvi] were provided by the University of Rochester Vaccine Evaluation Unit. All AIR antiserum experiments were performed blind: no prior knowledge of the amount of antigen each subject was inoculated with, the results of antiserum response as monitored by traditional assays, nor the identity of the placebo sample were divulged beforehand. Negative control mouse plasma was obtained from four-month old, female, 129Sv/J mice (original source Taconic, now bred in-house in an aseptic vivarium), and was collected following an IP injection with pentobarbital and a heart right ventricle puncture. In order to provide an appropriate sample volume for our study, the blood from five mice was pooled over heparin and centrifuged to remove red blood cells.

Chip Surface Amination

AIR substrates were diced from silicon wafers having a terminal, thermally grown silicon dioxide layer (Infotonics Technology Center). The chips were first cleaned in a basic solution of 70% 1 M sodium hydroxide: 30% ethanol for 30 minutes, then etched in a dilute solution of hydrofluoric acid until the silicon dioxide thickness reached 1381 Å (for macroarray experiments) or 1393 Å (for microarray experiments) as measured by spectroscopic ellipsometry (M2000 spectroscopic ellipsometer, JA Woollam). The slight discrepancy in the required silicon dioxide thickness is owed to the different attachment chemistries that we employed for each approach (vide infra). The surface functionalization procedure began by cleaning the chips in a bath of 1:1 hydrochloric acid and methanol for 30 minutes. The chips were then washed thoroughly with glass distilled deionized water (ddH2O) and dried under a stream of nitrogen. Next, the chips were then submersed in a 0.4% solution of γ-aminopropyl triethoxysilane (Sigma-Aldrich) in distilled, anhydrous toluene [xxxi]. After 15 minutes of gentle shaking, the chips were washed with ethanol, dried under a stream of nitrogen, and then cured at 100 °C for 15 minutes.

Surface Functionalization for Macroarrays

Once the chips had cooled to room temperature, a 0.5 mg/mL solution of para-phenylene diisothiocyanate (Sigma-Aldrich) in anhydrous dimethylformamide (DMF) was added to the chips. The chips were shaken gently in this solution for 30 minutes, removed from the bath, rinsed with DMF, rinsed with acetone, and then dried under a stream of nitrogen.

Macroarray Production and Imaging

HAs were manually arrayed in a volume of 1 μL at a final concentration of 20 μg/mL after a 1:1 dilution from a 2x stock in buffer (10 mM Na2HPO4, 10 mM NaH2PO4, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.2; MPBS) into a solution containing 10% glycerol and 0.01% Tween-20. Human IgG (GeneTex, Inc., GTX 77542; positive control) and fluorescein (Rockland Immunochemicals; negative control) antibodies were arrayed at a final concentration of 50 μg/mL in the same volume and spotting buffer dilution. Probe solutions were allowed to incubate for 10 minutes in an ambient environment, after which the chips were immediately immersed in a solution of blocking buffer (1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin [BSA; Sigma-Aldrich] in a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.2 [HBS]) for 45 minutes. The chips were then rinsed with MPBS buffer supplemented with 3 mM EDTA and 0.005% Tween-20 (MPBS-ET), and 150 μL of 100% human serum samples were pipetted onto the surface. It is anticipated that some variable sample dilution will have occurred, but it keeping the surface hydrated is required to ensure the activity of the arrayed proteins. After a 45 minute incubation period, the chips were rinsed with MPBS-ET and added to a shaking bath of MPBS-ET for 5 minutes. The chips were then rinsed with ddH2O, dried with nitrogen, and imaged on a benchtop reflectometer [xxv]. Reflectance values for each spot were compared to the reciprocal spot on a negative control chip (MPBS-ET only) and normalized to the anti-fluorescein negative control spot.

Surface Functionalization for Microarrays

Once the chips cooled to room temperature, they were added to an aqueous solution of 1.25% glutaraldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) in MPBS buffer and shaken for 60 minutes. The chips were finally washed with ddH2O, acetone, and ddH2O, and then dried under a stream of nitrogen.

Microarray Production and Imaging

After the glutaraldehyde addition, the chips were fully functionalized to allow for the covalent attachment of probe molecules via nucleophilic attack of a free amine. For microarrays, probe molecules were prepared separately and then added to sterilized 384-well plates (ABgene) at their individual final concentrations in an MPBS buffer containing 0.1% 12-crown-4 [xxxii] (Sigma-Aldrich). Hemagglutinins H1, H3, H5, and H6 were arrayed at a final concentration of 40 μg/mL, while H9 was arrayed at a final concentration of 50 μg/mL. Negative control probes consisted of anti-fluorescein (10 μg/mL) and human serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, 200 μg/mL); positive control probes consisted of antibodies to human IgG (100 μg/mL), and human IgM (Sigma-Aldrich, 100 μg/mL). The final concentrations of each probe molecule were determined such that each layer thickness, as observed by AIR, was equivalent. All probes were arrayed with eight replicates and a spacing of 300 μm using a Virtek ChipWriter Pro (Virtek Vision, Inc.). The arraying was performed at 70% relative humidity, and the spots were allowed to immobilize for 45 minutes in this environment. After the immobilization was complete, the chips were immediately immersed into a blocking solution containing 200 μg/mL BSA in HBS buffer for 60 minutes. The chips were then washed with ddH2O, and 100 μL of the target antisera were applied directly to wet chips. Target serum solutions were made at the appropriate concentrations into MPBS-ET buffer. Serum solutions were allowed to incubate on the chips for 60 minutes, after which each chip was rinsed with MPBS-ET and placed into a shaking solution of MPBS-ET for 5 minutes. The chips were washed again with ddH2O and dried under a stream of nitrogen. Dried chips were mounted onto a vacuum chuck and imaged using a prototype reflectometer (Adarza Biosystems, Inc.). All images were acquired at an integration time of 200 ms and a gain of 9.0 using LuCam capture software (Lumenera Corporation).

AIR Data Analysis

The mean spot intensity for all acquired array images were measured in ImageJ [xxxiii]. All array images were captured and processed as 8 bit files; therefore, reflectance intensity values are represented in arbitrary units on a scale of 0 – 255. The reflectance intensity was calculated for each set of probes as an average of the intensity from the eight replicate spots in a column. From this value, reflectance changes were computed as simple differences in intensity values between experimental (antiserum exposed) and control (MPBS-ET only) chips. Experimental intensity changes were then normalized to any small change in that of the negative control (anti-fluorescein in macroarray experiments and human serum albumin in microarray experiments).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Amanda Getty for donating naïve mouse plasma, the research teams responsible for performing and evaluating the original H5N1 vaccine trials, and Dr. Christopher Striemer of Adarza Biosystems, Inc. for providing the prototype reflectometer. We also thank the University of Rochester Human Immunology Center (NIH R24-AL054953) and the Elon Huntington Hooker Foundation (predoctoral fellowship for CRM) for supporting this research.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION: Expanded data sets for human antiserum microarray experiments, experiments with bird serum, and hemagglutinin homology model (11 pp.)

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- i.Germann TC, Kadau K, Longini IM, Macken CA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:5935–5940. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601266103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ii.de Jong JC, Claas EJC, Osterhaus ADME, Webster RG, Lim WL. Nature. 1997;389:554. doi: 10.1038/39218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- iii.World Health Organization. [accessed July 5, 2010];Epidemic and pandemic alert and response: Avian influenza. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/avian_influenza/en/index.html.

- iv.Ungchusak K, Auewarakul P, Dowell SF, Kitphati R, Auwanit W, Puthavathana P, Uiprasertkul M, Boonnak K, Pittayawonganon C, Cox NJ, Zaki SR, Thawatsupha P, Chittaganpitch M, Khontong R, Simmerman JM, Chunsutthiwat S. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:333–340. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- v.Moscona A. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1363–1373. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vi.Hiramatsu K. Lancet Infect Dis. 2001;1:147–155. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00091-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vii.de Jong MD, Tran TT, Truong HK, Vo MH, Smith GJ, Nguyen VC, Bach VC, Phan TQ, Do QH, Guan Y, Peiris JS, Tran TH, Farrar J. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2667–2672. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- viii.Avian influenza: Fact Sheet. World Organization for Animal Health; Estimate as of 2006. http://www.oie.int/eng/ressources/en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- ix.http://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/en/index.html

- x.Copeland CS, Doms RW, Bolzau EM, Webster RG, Helenius A. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:1179–1191. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.4.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xi.Wiley DC, Skehel JJ. Ann Rev Biochem. 1987;56:365–394. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.002053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xii.Ohmit SE, Victor JC, Rotthoff JR, Teich ER, Truscon RK, Baum LL, Rangarajan B, Newton DW, Boulton ML, Monto AS. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2513–2522. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xiii.Horimoto T, Takada A, Fujii K, Goto H, Hatta M, Watanabe S, Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, Ito M, Tagawa-Sakai Y, Yamada S, Ito H, Ito T, Imai M, Itamura S, Odagiri T, Tashiro M, Lim W, Guan Y, Peiris M, Kawaoka Y. Vaccine. 2006;24:3669–3676. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xiv.Li S, Liu C, Klimov A, Subbarao K, Perdue ML, Mo D, Ji Y, Woods L, Hietala S, Bryant M. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:1132–1138. doi: 10.1086/314713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xv.Treanor JJ, Wilkinson BE, Masseoud F, Hu-Primmer J, Battaglia R, O’Brien D, Wolff M, Rabinovich G, Blackwelder W, Katz JM. Vaccine. 2001;19:1732–1737. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00395-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xvi.Subbarao K, Chen H, Swayne D, Mingay L, Fodor E, Brownlee G, Xu X, Lu X, Katz J, Cox N, Matsuoka Y. Virology. 2003;305 doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xvii.For selected examples, see: Puzelli S, Di Trani L, Fabiani C, Campitelli L, De Marco MA, Capua I, Aguilera JF, Zambon M, Donatelli I. J Infect Diseases. 2005;192:1318–1322. doi: 10.1086/444390.Karron RA, Callahan K, Luke C, Thumar B, McAuliffe J, Schappell E, Joseph T, Coelingh K, Jin H, Kemble G, Murphy BR, Subbarao K. J Infect Diseases. 2009;199:711–716. doi: 10.1086/596558.Apisarnthanarak A, Erb S, Stephenson I, Katz JM, Chittaganpitch M, Sangkitporn S, Kitphati R, Thawatsupha P, Waicharoen S, Pinitchai U, Apisarnthanarak P, Fraser VJ, Mundy LM. Clin Infect Disease. 2005;40:e16–e18. doi: 10.1086/427034.Katz JM, Lim W, Bridges CB, Rowe T, Hu-Primmer J, Lu X, Abernathy RA, Clarke M, Conn L, Kwong H, Lee M, Au G, Ho YY, Mak KH, Cox NJ, Fukuda K. J Infect Diseases. 1999;180:1763–1770. doi: 10.1086/315137.Peng D, Hu S, Hua Y, Xiao Y, Li Z, Wang X, Bi D. Vet Immunol Immunopath. 2007;117:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2007.01.022.

- xviii.MacBeath G, Schreiber SL. Science. 2000;289:1760–1763. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5485.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xix.Michaud GA, Salcius M, Zhou F, Bangham R, Bonin J, Guo H, Snyder M, Predki PF, Schweitzer BI. Nat Biotech. 2003;21:1509–1512. doi: 10.1038/nbt910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xx.Chan SM, Ermann J, Su L, Fathman CG, Utz PJ. Nat Med. 2004;10:1390–1396. doi: 10.1038/nm1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xxi.Davies DH, Liang X, Hernandez JE, Randall A, Hirst S, Mu Y, Romero KM, Nguyen TT, Kalantari-Dehaghi M, Crotty S, Baldi P, Villarreal LP, Felgner PL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:547–552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408782102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xxii.Li B, Jiang L, Song Q, Yang J, Chen Z, Guo Z, Zhou D, Du Z, Song Y, Wang J, Wang H, Yu S, Wang J, Yang R. Infect Immun. 2005;73:3734–3739. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3734-3739.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xxiii.Qiu M, Shi Y, Guo Z, Chen Z, He R, Chen R, Zhou D, Dai E, Wang X, Si B, Song Y, Li J, Yang L, Wang J, Wang H, Pang X, Zhai J, Du Z, Liu Y, Zhang Y, Li L, Wang J, Sun B, Yang R. Microbes Infect. 2005;7:882–889. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xxiv.Lu J, Strohsahl CM, Miller BL, Rothberg LJ. Anal Chem. 2004;76:4416–4420. doi: 10.1021/ac0499165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xxv.Mace CR, Striemer CC, Miller BL. Anal Chem. 2006;78:5578–5583. doi: 10.1021/ac060473+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xxvi.Treanor JJ, Campbell JD, Zangwill KM, Rowe T, Wolff M. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1343–1351. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xxvii.Striemer CC, Mace CR, Carter JA, Mehta SD, Miller BL. Proc SPIE. 2009;7167:71670G1–71670G10. [Google Scholar]

- xxviii.Carrat F, Flahault A. Vaccine. 2007;25:6852–6862. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xxix.Sui J, Hwang WC, Perez S, Wei G, Aird D, Chen LM, Santelli E, Stec B, Cadwell G, Ali M, Wan H, Murakami A, Yammanuru A, Han T, Cox NJ, Bankston LA, Donis RO, Liddington RC, Marasco WA. Nature Struct Molec Biol. 2009;16:265–273. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xxx.Throsby M, van den Brink E, Jongeneelen M, Poon LL, Alard P, Cornelissen L, Bakker A, Cox F, van Deventer E, Guan Y, Cinatl J, ter Meulen J, Lasters I, Carsetti R, Peiris M, de Kruif J, Goudsmit J. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3942. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xxxi.Vandenberg ET, Bertilsson L, Liedberg B, Uvdal K, Erlandsson R, Elwing H, Lundstrom I. J Colloid Interf Sci. 1991;147:103–118. [Google Scholar]

- xxxii.Mace CR, Yadav AR, Miller BL. Langmuir. 2008;24:12754–12757. doi: 10.1021/la801712m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xxxiii.Abramoff MD, Magelhaes PJ, Ram SJ. Biophotonics Int. 2004;11:36–42. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.