Abstract

Background & Aims

Data on secular trends and outcomes of eosinophilic esophagitis (EE) are scarce. We performed a population-based study to assess the epidemiology and outcomes of EE in Olmsted County, Minnesota, over the last 3 decades.

Methods

All cases of EE diagnosed between 1976 and 2005 were identified using the Rochester Epidemiology Project resources. Esophageal biopsies with any evidence of esophagitis and/or eosinophilic infiltration were reviewed by a single pathologist. Clinical course (treatment, response and recurrence) was defined using information collected from medical records and prospectively via a telephone questionnaire. Incidence rates per 100,000 person years were directly adjusted for age and sex to the US 2000 population structure.

Results

A total of 78 patients with EE were identified. The incidence of EE increased significantly over the last 3 of the 5-year intervals (from 0.35 [0,0.87]/100000 person-years during 1991–1995 to 9.45 [7.13, 11.77]/100000 person-years during 2001–2005). The prevalence of EE was 55.0 (42.7, 67.2)/100000 persons as of January 1, 2006 in Olmsted County, Minnesota. EE was diagnosed more frequently in late summer/fall. The clinical course of patients with EE was characterized by recurrent symptoms (observed in 41% of patients).

Conclusions

The prevalence and incidence of EE is higher than previously reported. The incidence of clinically diagnosed EE increased significantly over the last 3 decades, in parallel with endoscopy volume and seasonal incidence, and was greatest in late summer/fall. EE also appears to be a recurrent relapsing disease in a substantial proportion of patients.

INTRODUCTION

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EE) was first reported three decades ago1, and has been increasingly recognized over the past 10 years 2–9. Adult patients present with dysphagia to solids 2, 6, 9, 10 and recurrent food impaction. 11 Diagnosis is made by the presence of eosinophilic infiltration of the mucosa (> 15–24 eosinophils/HPF depending on the study cutoff) 2, 4, 9, 11, 12. Successful treatment has been reported with oral and inhaled/swallowed topical steroids, dietary manipulation and esophageal dilation 13,12,5,9,14,10.

It remains unclear if the increasing case load of EE reflects a true increase in incidence or merely increased recognition No information on secular trends on the incidence of EE is currently available from the United States 3. A population based estimate from Europe 15 reported a marked increase in cases between 2001 and 2004. The clinical course of patients with EE has been described to be characterized by frequent recurrences in case series from referral centers 16. Limited information is available on the natural history and clinical coure of adult patients with EE particularly in a population based setting9.

We conducted a population-based study in Olmsted County, MN to 1) estimate the incidence of EE from January 1, 1976 through January 1st, 2005 and 2) assess the clinical course of EE over this same time period. In order to estimate the true incidence of EE in Olmsted County, we re-reviewed all esophageal biopsies that had any mention of eosinophils and/or esophagitis over the last 3 decades. Though the most recent guidelines for the diagnosis of EE17 suggest the exclusion of underlying GERD with either treatment trial with PPIs or 24 hour ambulatory testing, studies reporting on the epidemiology of EE prior to these guidelines being published3, 15 have used varying counts of esophageal eosinophilic infiltration with symptomatic esophageal dysfunction as the inclusion criteria for cases. Over the last few years, the interaction between GERD, EE and esophageal eosinophilic inflammation has been recognized18, 19, with realization, that overlap between these entities does exist. Given the time frame of this study, we have included patients with at least 15 eosinophils/HPF on esophageal biopsies with significant esophageal symptoms as documented in their medical records.

METHODS

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center Institutional Review Boards (IRB). This was a retrospective cohort study.

Setting

The Olmsted County population comprises approximately 120,000 persons of which 89% are white; sociodemographically, the community is similar to the US white population 20. County residents receive their medical care almost exclusively from 2 group practices: Mayo Medical Center and Olmsted Medical Center. The Mayo Clinic has maintained a common medical record system with its 2 affiliated hospitals (St. Mary’s and Rochester Methodist Hospital) for over 100 years. The system was further developed by the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP), which created similar indices for the records of other providers of medical care to local residents. Annually, over 80% of the entire population is attended by one or both of these 2 practices, and nearly everyone is seen at least once during any given 4-year period20. Therefore, the REP medical records linkage system also provides what is essentially an enumeration of the population from which samples can be drawn.

Case definition

Case identification using the REP consists of an electronic search which is designed to be sensitive followed by a chart review which increases specificity20. Given the absence of a ICD 9/HICDA code for EE during the time frame of this study, we used search terms, “esophagitis” (which was also combined with a text word search for “eosin”) and “food bolus impaction”, to identify 3456 patients in the REP database. This sensitive search is designed to identify all patients with these terms anywhere in their medical records (clinical notes and pathology reports). A separate search for these terms was also run in the Mayo pathology database to ensure complete identification of all cases. All individuals residing in Olmsted County at the time of their diagnosis and meeting the following inclusion criteria (from 1976–2005) were included as cases: Eosinophilic Esophagitis: endoscopy with esophageal biopsies showing >/=15 eosinophils/HPF.

Validation of case identification

To ensure complete case identification, 2 additional data sets were examined. All cases with a diagnosis of “esophageal ring(s)” that had undergone endoscopy were identified in Olmsted County from the REP database over the time frame of this study (N=377) and medical records of a random sample of 100 subjects were reviewed for evidence of the above inclusion criteria. In addition, medical records of a random sample of 100 adult patients who had responded to a previous gastrointestinal symptom questionnaire study in Olmsted County21, 22 (endorsing the symptom of dysphagia) and had undergone endoscopy (N=127) were reviewed for evidence of the above inclusion criteria.

Data collection

The complete medical records of each subject were reviewed by a nurse abstractor. All possible cases for inclusion were independently reviewed by one of the investigators to confirm findings.. The following information was collected on all patients: demographics (age/gender), presenting symptoms and duration of symptoms, associated allergic diathesis, family history of EE and/or food impactions, endoscopic findings (on initial and any follow up endoscopies), results and location of esophageal biopsies, results of any tests to exclude any other esophageal pathology (radiology, manometry, pH studies done within 1 year of the diagnosis of EE), treatment (with dilations, medications or both), timing and number of recurrences of EE and/or food impactions.

The pertinent clinical and laboratory data collected was entered into a pre-coded data form. The collected data was keyed into a database from the data forms with independent verification, was edited by a range and consistency check program, and a SAS data set was created for analysis.

Pathology

All biopsies with any mention of eosinophils OR esophagitis OR with a diagnosis of EE were re-reviewed by an experienced gastrointestinal pathologist (TCS). The most inflamed area in the biopsy was selected and the eosinophil count calculated in one high power field in that area (one high power field measures 0.625 mm). For this study, we defined EE as the presence of greater than or equal to 15 eosinophils per high power field in esophageal biopsies23.

Prospective data collection

All patients were also contacted with a telephone call using an IRB approved telephone script. Each subject was asked questions on recurrence of dysphagia and severity of dysphagia in the last three months, as well as any treatment of EE or food impaction either endoscopically or with medications.

Statistical analysis

For the calculation of incidence rates, the entire population of Olmsted County was considered to be at risk, and the denominator age- and sex-specific person-years (p-y) were estimated from decennial census data 24. Rates were directly age and sex-adjusted to the population structure of the 2000 U.S. Census. The associations of gender (male gender was used as the reference group), age, and calendar year (1976–1986 was used as the reference group) with the incidence rates were assessed using Poisson regression models (PROC GENMOD in SAS®) in which the number of observed cases for each sex-age-calendar year category was modeled as a function of sex, age and calendar year with the corresponding (log) person-years as an offset. Time to initial recurrence was summarized using the Kaplan-Meier method. We also assessed the correlation between presenting symptoms and endoscopic appearance with the time intervals across the previous three decades. Using endoscopic appearance (normal versus abnormal) as the outcome variable, univariate and multivariable analyses were performed to assess associations with age, gender, time period (1991–2000 and 2001–2005) and symptoms (food impaction and reflux symptoms).

To assess the seasonal variation in the diagnosis of EE, the date of the first esophageal biopsy showing >/= 15 eosinophils/hpf was taken as the date of diagnosis of EE. Statistical analysis of the distribution of diagnosis months used the Rayleigh test for directional statistics. This test assesses whether the dates of diagnosis are distributed uniformly (randomly) around the months of the year (see Batschelet, E. Circular Statistics in Biology, Academic Press, 1981, p 54)

With 78 cases, the study had 80% power to detect a relative change in rates (rate ratio) as small as 3.0 over a 30 year period (assuming a uniform distribution of cases over the study period). Assuming a linear trend, this would be equivalent to being able to detect an annual rate ratio of 1.04 per year for a 30-year study, while for a 10-year study the detectable annual rate ratio would be 1.12 per year.

RESULTS

Case Identification

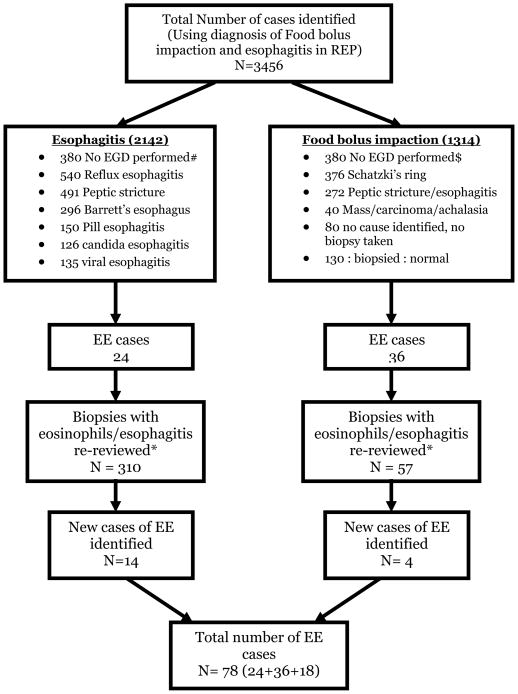

Figure 1 describes the process of identification of 78 patients with EE. 29%% (23/78) of patients with EE were children (patients less than 18 years old at diagnosis).

Figure 1. Flowsheet describing case identification.

MS: Multiple sclerosis, PD: Parkinson’s disease

#: Patients with esophagitis mentioned in medical records, radiology (barium x ray) reports

$: Patients treated for food bolus impaction in the emergency room successfully with glucagon, not needing endoscopy, those with a mention of this diagnosis in the medical records

*: Total number of patients with available biopsies to review (not all patients with an endoscopic diagnosis of reflux esophagitis were routinely biopsied)

Validation of case identification

Review of the random sample of 100 subjects with a diagnosis of “esophageal ring” who had undergone endoscopy identified 2 subjects with esophagitis and/or eosinophils mentioned in the pathology reports. These had already been reviewed by the pathologist as described above (and confirmed not to meet inclusion criteria specified above as per current definition) using our original case identification strategy. Review of the random sample of 100 subjects with dysphagia in Olmsted County who had endoscopy, revealed only one patient with a diagnosis of EE (who had also been identified as a case in our initial case identification with the search term “esophagitis”).

Epidemiology

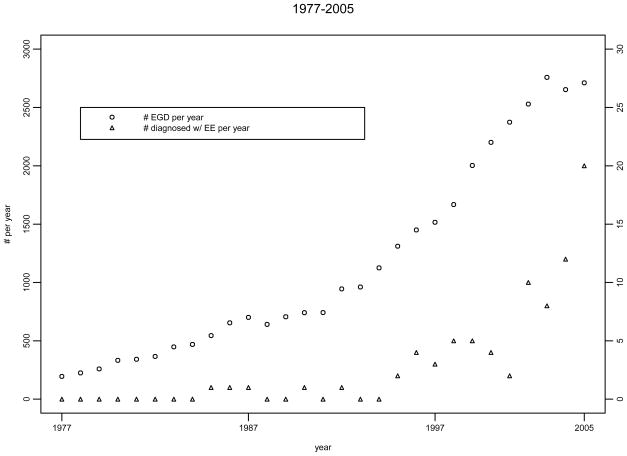

For calculation of incidence rates, patients diagnosed from 1/1/1976 to 1/1/2005 were included (78 patients with EE). The cumulative incidence rates of EE in Olmsted County are shown in Table 1. Figure 2 displays the age and sex adjusted incidence rates of EE over 3 decades. The Poisson regression model indicated the incidence of EE increased over time (p<0.001, Figure 2) and also increased with age (p=0.02). No overall association was detected for gender, though males had somewhat higher rates over the complete study period.. For calculation of prevalence rates, patients diagnosed from 1/1/1976 to 1/1/2005 and alive on 1/1/2006 were included (78 patients with EE). The prevalence of EE in this time span was 55.0/100000 persons, as shown in Table 1. In a further effort to assess the influence of endoscopy volume on EE detection rates, we also gathered data on the total number of upper endoscopies performed per year in Olmsted County using the REP resources, and plotted the number of endoscopies and the number of cases of EE diagnosed in each year (Figure 3). Although this may simply reflect an ecological correlation, it appears the number of diagnosed cases of EE and the volume of upper endoscopies have both increased in parallel over time.

Table 1.

Incidence rates and prevalence (1/1/2006) of EE in Olmsted County MN from 1976–2005

| Age adjusted – Females | Age adjusted – Males | Age & Sex adjusted | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence of EE | 2.04 (1.35,2.74) | 2.73 (1.91,3.54) | 2.39 (1.85,2.93) |

| Prevalence of EE | 46.6 (31.0,62.3) | 60.9 (42.9,78.9) | 54.0 (42.0,66.1) |

Incidence Rates: include patients diagnosed before 1/1/2006 and were Olmsted County residents. Prevalence rates: include patients who were diagnosed before 1/1/2006, were alive on 1/1/2006, and were Olmsted County residents on 1/1/2006

Figure 2.

Incidence of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Olmsted County, MN over 6 five year intervals (1976–2005)

EE: eosinophilic esophagitis;

Figure 3.

Secular trends in endoscopy volume per year and number of EE cases diagnosed per year

Clinical features

Table 2 describes the demographic and clinical feature of patients with EE in the population. Most of the patients with EE presented with dysphagia. Approximately a third presented with food impaction. A substantial proportion of patients reported symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux, in addition to a history of asthma and seasonal allergies. The clinical features of adults and children with EE did differ; 61% of children presented with dysphagia compared to 93% of adults. Food impaction was more common in adults (42%) compared to children (22%). Acid regurgitation symptoms were also less common in children (22%) compared to adults (38%). A substantial fraction of patients (23% of adults and 38% of children) had a family history of EE. Overall, 23 (29%) of patients were on PPIs/H2Ras at the time of diagnosis. The majority of EE patients (64%) had normal appearing mucosa on endoscopy. Rings and fissures were commonly seen. Some patients had associated mild esophagitis and strictures.

Table 2.

Descriptive data for EE cases

| Variable | Adult cases (n=55) | Pediatric cases (n=23) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 37 ± 11 | 10 ± 6 |

| Male Gender (n,%) | 29 (52.7%) | 15 (65.2%) |

| Dysphagia (n,%) | 51 (92.7%) | 14 (60.9%) |

| Food Impaction (n,%) | 23 (41.8%) | 5 (21.7%) |

| Heartburn (n,%) | 30 (54.5%) | 4 (17.4%) |

| Acid Regurgitation (n,%) | 21 (38.2%) | 5 (21.7%) |

| Abdominal Pain (n,%) | 12 (21.8%) | 7 (30.4%) |

| Nausea (n,%) | 3 (5.4%) | 3 (13.0%) |

| Vomiting (n,%) | 10 (18.2%) | 10 (43.5%) |

| Seasonal allergies (n,%) (data available on 30 adult and 13 pediatric patients) | 15 (50.0%) | 7 (53.8%) |

| Food allergies (n,%) (data available on 30 adult and 14 pediatric patients) | 11 (36.7%) | 8 (57.1%) |

| History of asthma (n,%) (data available on 28 adult and 11 pediatric patients) | 11 (39.3%) | 7 (63.6%) |

| Family History $(n,%) (data available on 39 adult and 16 pediatric patients) | 9 (23.1%) | 6 (37.5%) |

| Endoscopic features (may be in more than one category and may be in the OTHER category more than once) | ||

| Normal | 29 (52.7%) | 21 (91.3%) |

| Rings | 18 | 1 |

| Strictures* | 6 | 0 |

| Esophagitis # | 5 | 2 |

| Longitudinal fissures | 12 | 7 |

| Histologic diagnosis obtained by: | ||

| Proximal Bx (n,%) | 14 (25.5%) | 0 |

| Distal Bx (n,%) | 16 (29.1%) | 9 (39.1%) |

| Proximal + Distal Bx (n,%) | 23 (41.8%) | 14 (60.9%) |

| Mean Eosinophil Counts | ||

| 15–20 (n,%) | 7 (12.7%) | 2 (8.7%) |

| 20–30 (n,%) | 14 (25.5%) | 7 (30.4%) |

| 31–50 (n,%) | 11 (20.0%) | 6 (26.0%) |

| > 50 (n,%) | 23 (41.8%) | 8 (34.9%) |

reflects information as recorded in medical records (not verified by endoscopic or histologic confirmation)

6 patients with EE had strictures, of which 2 were mid-esophageal and 4 were distally located;

7 patients with EE had associated esophagitis of which 5 were Los Angeles (LA) grade A, and 2 were LA grade B

Variables influencing endoscopic appearance

Univariately, time period was associated with appearance, (a greater odds for normal endoscopic appearance in the earlier time period), after adjusting for age and gender this was no longer significant. Age was also associated with appearance (increasing age associated with decreasing odds for normal appearance). It should be noted that older age cases were observed in the later time period so that these two factors are confounded. In contrast presentation with food impaction was modestly associated with decreased odds for normal appearance after adjusting for age, gender and time period (see table 3).

Table 3.

Factors influencing endoscopic appearance

| Variable | OR [95% CI] for Normal appearance | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age † (OR per year) | 0.97 (0.94,1.00) | 0.05 |

| Male gender† | 1.08 (0.42,2.83) | 0.87 |

| Time Period of study (1991–2000 Vs 2001–2005) † | 0.34 (0.06,1.78) | 0.20 |

| Symptoms | ||

| Food impaction § | 0.42 (0.15,1.16) | 0.09 |

| Heartburn § | 0.91 (0.31,2.72) | 0.87 |

| Dysphagia § | 0.40 (0.07,2.27) | 0.30 |

| Acid Regurgitation § | 1.59 (0.53,4.76) | 0.41 |

OR’s adjusted for age and gender

OR’s adjusted for age, gender and time period

Diagnosis

Diagnosis was made by proximal biopsies alone in approximately 18% of patients, distal biopsies in a third and on both distal and proximal biopsies in the rest (see table 2), given that this was a retrospective study. Of the 37 patients who had biopsies taken from the proximal and distal esophagus, 25 patients (66%) had > 15 eosinophils/HPF in both proximal and distal biopsies, 10 patients (26%) only in distal biopsies and the remainder three in only proximal esophageal biopsies. 24 hour ambulatory pH studies were performed within a year of diagnosis in 5 patients with EE: distal esophageal acid exposure was normal in 4 patients and mildly abnormal in 1 patient (total time pH less than 4 in the distal esophagus was 6.3%).

Treatment

Table 3 (available online as supplementary material) displays data on treatment. Most were prescribed medications; 51% receiving inhaled steroids for four to eight weeks. 40% of patients also received PPIs for six to twelve weeks. A fifth of patients were treated with medications and esophageal dilations. No patient was treated with dilation alone at diagnosis.

Seasonal variation in diagnosis

The distribution of the month of diagnosis is shown in figure 4, also showing results of the Rayleigh statistical test for a uniform distribution. The test revealed a nonrandom diagnosis date distribution, with a “mean direction” indicating a late summer/early fall preponderance.

Figure 4.

Distribution of month of diagnosis of incident cases of EE in Olmsted County from 1976–2005.

Clinical Course

We defined recurrence as recurrent dysphagia and/or food impaction treated medically and/or endoscopically. Overall, 46 patients with EE had no recurrences, while 32 patients had one or more recurrences (17 patients had 1 recurrence and 13 patients had 2 recurrences). The two and four year cumulative recurrence rates for patients with EE were 31.5 % (95% CI: 19.6, 41.7) and 49.2 % (95% CI: 33.6, 61.1), respectively. The median (range) follow up in patients with EE without recurrence was 38.0 months (0 days to 12.8 years). Figure 5 is a Kaplan Meier curve describing recurrences in patients with EE (available online as supplementary material).

Prospective follow up

Overall, 56 of the 78 patients (67%) provided information via telephone. Twenty seven patients (48%) reported experiencing dysphagia within the last 3 months. Of these patients 11 (41%) reported symptoms “often” or “usually” while the rest experienced dysphagia “sometimes”. In particular, 7 patients (13%) reported symptoms either once or more often a day with 6 (11%) experiencing dysphagia once or more times a week and the rest less frequently. A total of five (9%) patients also reported an emergency room visit in the last year for food impaction and 23 (41%) patients reported being treated with either dilation or medications or both in the past one year.

DISCUSSION

In this population-based study from the United States, we report secular trends in the epidemiology of eosinophilic esophagitis over the last three decades using robust case identification techniques as well a single histology standard. We observed a higher incidence of EE than that reported by previous studies. We found that the incidence of documented EE appears to have increased significantly over the last 3 decades. This increase has however paralleled the increase in endoscopy volume over the same time period.

The epidemiology of EE has been inadequately defined, with data on adults in the United States being particularly scarce. Controversy continues on whether the increased number of cases in recent years is a reflection of a true increase in incidence or merely increased recognition 15, 25, 26. Noel3 reported initial estimates of incidence in a pediatric population (0.90 to 1.28/10000 population from 1999 to 2003) but considered these to be an underestimate. They did not find that these estimates differed over the 4 year period. These estimates are consistent with our estimate of the age and sex adjusted incidence in the pediatric population in Olmsted County: 0.69 (95% CI: 0.42, 0.96) per 100000 population per year. Estimates of incidence in adults have been reported from Europe15 (average incidence of 1.4 cases/100000 population per year over a 15 year period). This is somewhat lower than our estimate of 1.70/100000 population per year for EE. This may be partly a reflection of our lower cutoff (which is now endorsed by the American Gastroenterology Association 23), as well as the re-review of slides by our pathologist using a consistent and uniform criteria. Our prevalence estimates (56.1/100000 population of patients with EE) are higher than those reported by Straumann (23/100000 population, with estimates until 2004). A recent population-based study reported the prevalence of EE (symptomatic and asymptomatic) to be 1.1% (when using a diagnostic criteria of >/= 15 eosinophils/HPF)27. Prevalence estimates from our study are closest to these estimates, but our results include only symptomatic patients.

Some studies have attempted to differentiate between a true increase in EE cases versus increased recognition. Cherian et al26 reanalyzed esophageal biopsies from pediatric patients and found a statistically significant increase in prevalence over the 3 years. Vanderheyden et al however found that 25 the proportion of EE patients did not appreciably change between 1995 and 2005. The increase in EE incidence in Olmsted County in parallel to the utilization of endoscopy as seen in Figure 3 raises the possibility of increased endoscopy volume contributing to the rise in total number of EE cases.

Food and aero allergens are thought to play a crucial role in inducing esophageal eosinophilic inflammation.28–30 Fogg et al 31 reported a patient with EE who had symptomatic and biopsy proven exacerbations of symptoms during pollen seasons with quiescence in the winter months. They hypothesized that a potential mechanism of pollen-induced EE is deposition of pollen in the nares and pharynx, with subsequent swallowing of nasal secretions and deposition of pollen in the esophagus similar to oral allergy syndrome. Seasonal variation in the degree of esophageal eosinophilia in has been reported by others32,33. Our finding of early summer/fall preponderance in the diagnosis of EE over the last 3 decades is the first report of seasonal variation in EE from a population-based perspective. This seasonal variation in diagnosis may be a surrogate marker (albeit imperfect) of the clinical activity of this disease, with more marked symptoms in periods of more intense allergen exposure leading to a higher likelihood of clinical testing and diagnosis.

Despite being the first large population based study from the United States, this study has some potential limitations. Given that there is no ICD code for EE in the REP database, we began identification of patients with EE by searching for all patients with a diagnosis of esophagitis and food impaction. We thought this would be the most ‘sensitive’ way of beginning case identification: this led to shortlisting almost 4000 cases over the 30 year interval: however we recognize that this strategy may have still underestimated the prevalence of EE. We attempted to minimize this limitation by having an expert gastrointestinal pathologist review all pathology slides with any mention of eosinophilic infiltration, using consistent diagnostic criteria. This identified an additional 18 patients with EE. We also attempted to further validate our case finding strategy by reviewing charts of two additional groups of patients who may have underlying EE: those with dysphagia and those with esophageal rings (undergoing endoscopy secondary to dysphagia); we did not find evidence of missed cases. Exclusion of underlying GERD was difficult in this study given the time frame of cases included (upto 2005) which precedes the most recent guidelines published in 2007. While we recognize this, we believe inclusion of cases with significant esophageal symptoms (more than 90% of adult patients had dysphagia and/or food impaction) decreases misclassification. Pediatric patients routinely underwent acid suppression before endoscopy. We also recognize that the study cannot estimate asymptomatic EE. Though the incidence of EE appears to be increasing in this study, as seen in Figure 3, it is possible that increase in rates of endoscopic evaluation and acquisition of esophageal biopsies over the last three decades may be responsible in part for this increase. While there appears to be corresponding increases in the incidence of EE and endoscopic volumes in Olmsted County, endoscopic volumes may be increasing due to a number of reasons (such as Barrett’s esophagus surveillance and changing diagnostic algorithms). The impression may simply reflect ecological correlation and an assessment of direct association would need a different study design. Studies in the pediatric age group however counter this argument, with a significant increase in the number of cases of EE being diagnosed despite the number of esophageal biopsies remaining comparable over time3.

In conclusion, the incidence and prevalence of EE appear to be higher than those reported previously. It appears that there has been a true increase in the incidence of EE in the community over the past three decades, with a preponderance of cases diagnosed in the late summer/fall, perhaps reflecting the appearance and/or presence of a yet unidentified environmental etiology. Increase in endoscopy volume may be a contributing factor to this finding.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by Glaxo SmithKline and the National Institutes of Health (U01DK065713-02).

We would like to thank Judy Peterson for assistance in the data collection and preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Picus D, Frank PH. Eosinophilic esophagitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1981;136:1001–3. doi: 10.2214/ajr.136.5.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Potter JW, Saeian K, Staff D, Massey BT, Komorowski RA, Shaker R, Hogan WJ. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults: an emerging problem with unique esophageal features. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:355–61. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02713-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noel RJ, Putnam PE, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilic esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:940–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200408263510924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liacouras CA. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37 (Suppl 1):S23–8. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200311001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liacouras CA, Spergel JM, Ruchelli E, Verma R, Mascarenhas M, Semeao E, Flick J, Kelly J, Brown-Whitehorn T, Mamula P, Markowitz JE. Eosinophilic Esophagitis: A 10-Year Experience in 381 Children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:1198–1206. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00885-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arora AS, Yamazaki K. Eosinophilic esophagitis: asthma of the esophagus? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:523–30. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00236-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vitellas KM, Bennett WF, Bova JG, Johnston JC, Caldwell JH, Mayle JE. Idiopathic eosinophilic esophagitis. Radiology. 1993;186:789–93. doi: 10.1148/radiology.186.3.8430189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teitelbaum JE. Natural history of primary eosinophilic esophagitis: a follow up of 30 adult patients for up to 11.5 years. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;38:358–9. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200403000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Straumann A, Spichtin HP, Grize L, Bucher KA, Beglinger C, Simon HU. Natural history of primary eosinophilic esophagitis: a follow-up of 30 adult patients for up to 11.5 years. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1660–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vasilopoulos S, Murphy P, Auerbach A, Massey BT, Shaker R, Stewart E, Komorowski RA, Hogan WJ. The small-caliber esophagus: an unappreciated cause of dysphagia for solids in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:99–106. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.118645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desai TK, Stecevic V, Chang CH, Goldstein NS, Badizadegan K, Furuta GT. Association of eosinophilic inflammation with esophageal food impaction in adults. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:795–801. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00313-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arora AS, Perrault J, Smyrk TC. Topical corticosteroid treatment of dysphagia due to eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:830–5. doi: 10.4065/78.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Konikoff MR, Noel RJ, Blanchard C, Kirby C, Jameson SC, Buckmeier BK, Akers R, Cohen MB, Collins MH, Assa’ad AH, Aceves SS, Putnam PE, Rothenberg ME. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fluticasone propionate for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1381–91. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen MS, Kaufman AB, Palazzo JP, Nevin D, Dimarino AJ, Jr, Cohen S. An audit of endoscopic complications in adult eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1149–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Straumann A, Simon HU. Eosinophilic esophagitis: escalating epidemiology? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:418–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helou EF, Simonson J, Arora AS. 3-yr-follow-up of topical corticosteroid treatment for eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2194–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, Gupta SK, Justinich C, Putnam PE, Bonis P, Hassall E, Straumann A, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1342–63. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ngo P, Furuta GT, Antonioli DA, Fox VL. Eosinophils in the esophagus--peptic or allergic eosinophilic esophagitis? Case series of three patients with esophageal eosinophilia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1666–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spechler SJ, Genta RM, Souza RF. Thoughts on the complex relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1301–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melton LJ., 3rd History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 1996;71:266–74. doi: 10.4065/71.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jung HK, Halder S, McNally M, Locke GR, 3rd, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ. Overlap of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and irritable bowel syndrome: prevalence and risk factors in the general population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:453–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choung RS, Locke GR, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ. Do distinct dyspepsia subgroups exist in the community? A population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1983–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, Gupta SK, Justinich C, Putnam PE, Bonis P, Hassall E, Straumann A, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Children and Adults: A Systematic Review and Consensus Recommendations for Diagnosis and Treatment Sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute and North American Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1342–1363. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glenski WJ, Klee GG, Bergstralh EJ, Oesterling JE. Prostate-specific antigen: establishment of the reference range for the clinically normal prostate gland and the effect of digital rectal examination, ejaculation, and time on serum concentrations. Prostate. 1992;21:99–110. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990210203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vanderheyden AD, Petras RE, DeYoung BR, Mitros FA. Emerging eosinophilic (allergic) esophagitis: increased incidence or increased recognition? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:777–9. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-777-EEAEII. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cherian S, Smith NM, Forbes DA. Rapidly increasing prevalence of eosinophilic oesophagitis in Western Australia. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:1000–4. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.100974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ronkainen J, Talley NJ, Aro P, Storskrubb T, Johansson SE, Lind T, Bolling-Sternevald E, Vieth M, Stolte M, Walker MM, Agreus L. Prevalence of oesophageal eosinophils and eosinophilic oesophagitis in adults: the population-based Kalixanda study. Gut. 2007;56:615–20. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.107714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akei HS, Mishra A, Blanchard C, Rothenberg ME. Epicutaneous antigen exposure primes for experimental eosinophilic esophagitis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:985–94. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mishra A, Hogan SP, Brandt EB, Rothenberg ME. An etiological role for aeroallergens and eosinophils in experimental esophagitis. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2001;107:83–90. doi: 10.1172/JCI10224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mishra A, Rothenberg ME. Intratracheal IL-13 induces eosinophilic esophagitis by an IL-5, eotaxin-1, and STAT6-dependent mechanism. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1419–27. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fogg MI, Ruchelli E, Spergel JM. Pollen and eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:796–7. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(03)01715-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Onbasi K, Sin AZ, Doganavsargil B, Onder GF, Bor S, Sebik F. Eosinophil infiltration of the oesophageal mucosa in patients with pollen allergy during the season. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:1423–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang FY, Gupta SK, Fitzgerald JF. Is there a seasonal variation in the incidence or intensity of allergic eosinophilic esophagitis in newly diagnosed children? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:451–3. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000248019.16139.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teitelbaum JE, Fox VL, Twarog FJ, Nurko S, Antonioli D, Gleich G, Badizadegan K, Furuta GT. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children: immunopathological analysis and response to fluticasone propionate. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1216–25. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Assa’ad AH, Putnam PE, Collins MH, Akers RM, Jameson SC, Kirby CL, Buckmeier BK, Bullock JZ, Collier AR, Konikoff MR, Noel RJ, Guajardo JR, Rothenberg ME. Pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: an 8-year follow-up. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:731–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]