Abstract

Discovery of antimicrobial peptides (AMP) is to a large extent based on screening of fractions of natural samples in bacterial growth inhibition assays. However, the use of bacteria is not limited to screening for antimicrobial substances. In later steps, bioengineered “bugs” can be applied to both production and characterization of AMPs. Here we describe the idea to use genetically modified Escherichia coli strains for both these purposes. This approach allowed us to investigate SpStrongylocins 1 and 2 from the purple sea urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus only based on sequence information from a cDNA library and without previous direct isolation or chemical synthesis of these peptides. The recombinant peptides are proved active against all bacterial strains tested. An assay based on a recombinant E. coli sensor strain expressing insect luciferase, revealed that SpStrongylocins are not interfering with membrane integrity and are therefore likely to have intracellular targets.

Key words: recombinant, purification, fusion protein, permeabilization, luciferase, sea urchin, Escherichia coli

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), often referred to as host defence peptides,1,2 are identified from a variety of phyla from plants and invertebrates to vertebrates. According to the Antimicrobial Peptide Database, more than 1,500 AMPs have been discovered to date (http://aps.unmc.edu/AP/main.php).3 The peptides show an enormous variety of sequence and structure, but certain features are common. Most naturally occurring AMPs carry a net positive charge, are amphipathic and are usually composed of less than 100 residues. They often display a wide range of activity, including antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral and even antitumor activities,4 thereby making them interesting within the context of drug discovery and development.

AMP discovery is to a large extent based on screening of fractions of natural samples in bacterial growth inhibition assays. When it comes to production and characterization of newly discovered AMPs, however, there exists a variety of different approaches. In our article “Two recombinant peptides, SpStrongylocins 1 and 2, from Strongylocentrotus purpuratus, show antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria”5 we chose to make use of recombinant Escherichia coli strains to both produce and characterize the AMPs SpStrongylocins 1 and 2. The original peptide strongylocin was discovered in the green sea urchin S. droebachiensis.6 Due to limiting amounts of peptide, only the primary amino acid sequence and MIC values for a set of four bacterial strains were determined. The homologous peptide from the closely related species, S. purpuratus were at that time only available as clones from a cDNA library.5 The general idea was to produce and characterize this peptide without prior direct isolation or chemical synthesis.

AMP Production

Due to the small amount of pure peptide directly recovered from isolates, further studies always depend on a strategy to recover more of the material of interest. This is necessary to exploit their mode of action and their pharmaceutical potential. As it turned out, it also is one of the bigger challenges when studying more complex AMPs. In general, there are three different approaches that can be employed: direct isolation of peptides from natural sources, chemical synthesis or recombinant expression of peptides in transgenic organisms.

Although most AMPs are produced in their host organisms, the direct recovery of AMPs from host species is neither economically nor practically feasible and might even result in environmental issues. This applies especially for peptides isolated from species that occur in low numbers. In addition, peptide expression in the original host can be extremely low or affected by unknown environmental factors resulting in problems when scaling up. In an attempt to extract more of the original strongylocins isolated from the green sea urchin S. droebachiensis, we extracted the hemolymph of 500 animals compared to 66 for the original discovery.6 However, we were not able to extract the strongylocins in considerable amounts. The urchins had been harvested at a different sampling site at a different season, and this seemed to strongly influence the outcome since the extraction conditions as such remained identical. Though it is known that expression of a number of AMPs can be induced upon pathogenic challenge,2 the health status of sampled wild animals is not predictable. Therefore, it is very likely that conditions at the sampling site in general strongly influence discovery rates of AMPs and other bioactive compounds, and that many potentially interesting molecules have slipped discovery.

Chemical synthesis of short amino acid sequences is economically viable. However, synthesis of sequences with more than ten amino acids in length is expensive. If the sequence of a peptide contains one or more disulfide bridges, this is likely to result in difficulties during synthesis, and therefore production costs will increase substantially. We concluded that the recombinant expression system would be the most cost-efficient method for large-scale production of SpStrongylocins probably also with respect to future production of similar AMPs.

There are many eukaryotic host systems available for protein production in general, such as the yeasts Pichia pastoris,7–9 Saccharomyces cerevisiae10 and Yarrowia lipolytica,11 the baculovirus expression system in insect cells,12–14 plants and human cells.15–18 Although eukaryotic hosts usually improve the production of proteins, especially those that require post-translational modifications, these strategies are time-consuming and costly processes. The bacterium E. coli on the other hand is one of the most commonly used hosts for production of proteins. It can grow rapidly and a large scale production can easily be establish, while using cheaper substrates than the other expression hosts19 and might therefore be a good choice for AMP production.

Production of recombinant AMPs benefits from experiences in recombinant expression of proteins. Production of proteins, whether for biochemical analysis, therapeutics or structural studies, requires the success of three individual factors: expression, solubility and purification.20 Host organisms such as S. cerevisiae,21 insect cells,22 mammalian cells23 and even plants24 have been used to express peptides. However, E. coli still remains a popular choice as host organism for recombinant AMP production if no refolding or post-translation modification is required to restore its biological activity.25–31

The toxicity of AMPs to microorganisms requires that the host is able to tolerate the toxic peptides or that the toxicity of the recombinant peptides is masked. In order to successfully express toxic proteins, Miroux and Walker described two new mutant strains of E. coli BL21 (DE3)32 which are frequently used to overcome the toxicity associated with overexpressing recombinant proteins.33–38 In addition, strategies to cover the toxicity of AMPs have been employed, including the introduction of an anionic preproregion to neutralize the cationic charge of AMPs31,39 or tandem repeats of an acidic peptide-antimicrobial peptide fusion.40 Other approaches use different fusion carrier proteins such as glutathione G-transferase,28,29 Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane protein, Staphylococcus aureus protein A, the duplicated IgG-binding domains of protein A,29 thioredoxin A,26 the green fluorescent protein,41,42 bovine prochymosin25 or the truncated protein PurF fragment F4.43 The following AMPs have been produced using the methods described above: LL-37,28 lactoferricin,39 human neutrophil peptide 1 (HNP-1), cecropin-melittin hybrid,29 bombinin, indolicidin, melittin, tachyplesin I,43 sarcotoxin IA,41 designated P2,25 human β-defensin 5 (HBD5) and 6.26

In our study we tried several different N-terminal affinity purification tags, in order to express and purify SpStrongylocins. Production of His-tagged (in pET21b including an enterokinase site), S-, His-tagged (in pET30-EK/LIC including a thrombin and an enterokinase site) and Strep-tagged (modified from pET30-EK/LIC with SpStrongylocins insert without cutting sites) SpStrongylocins were not successful when expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3). However, for the combined S- and His-,we harvested 1 to 1.5 milligram peptide per litre of culture medium when the E. coli BL21 (DE3) strain C43 was employed as expression host.5 On the other hand, the Strep-tagged peptide was not expressed in detectable amounts under these conditions (His-tagged expression was not tested in BL21(DE3) C43). The overexpression of SpStrongylocins most likely benefits from mutations in C43(DE3) which might affect the activity of the T7 RNA polymerase, and reduce the amount of polymerase produced.32 The mutations may also improve the stability of the expression plasmid.33 Since the attempts to express the SpStrongylocins with a Strep-tag did not result in any detectable production of the peptide, although the same strains and conditions were used for production, we conclude that both the usage of a negatively charged tag partly neutralizing the positive charge of the recombinant expressed construct, and the fitting expression strain are a prerequisite for effective peptide production.

Bugging Bacteria

The success of bacteria is to a large extent based on their fast transcriptional responses to changes in their environment. This provides an opportunity to “listen” to the bacteria's reaction to an antibacterial challenge from novel compounds and thereby deduce the probable mode of action. This can be done e.g., by tracing the overall changes in the transcriptional pattern as a response to AMPs in transcriptomic studies.44,45 Though whole-transcriptome studies give a deeper insight into the transcriptional changes resulting from AMP treatment, they are time consuming and very likely to be hampered by a large extent of mechanism independent responses. Direct monitoring of relevant stress response genes by reporter fusions, on the other hand, as for the SOS response in E. coli,46 though mostly used for conventional antibiotic detection, might give fast insight into the potential mode of action of novel antimicrobial peptides targeting DNA replication. Finally it is also possible to use genetically manipulated bacteria which amplify detection of specific effects on central cell functions, like protein expression, DNA replication and membrane integrity.47–49 This can be done by directly coupling reporter-gene expression or reporter-enzyme activation to cellular events. As for example protein expression by monitoring the expression from an inducible promoter as suggested in Galuzzi et al.47 or membrane integrity by monitoring enzyme activity in response to conditional uptake of substrate.50

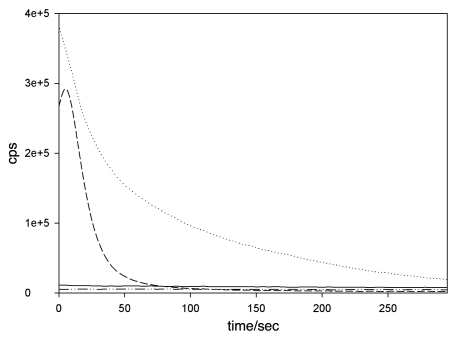

When dealing with AMPs there are supposedly two main modes of action which need to be distinguished. Peptides can affect cell viability either by directly interfering with bacterial membrane integrity or by binding to specific intracellular targets after transfer across the bacterial membrane(s).51 It is only logical to elucidate first if a peptide interferes with membrane integrity before trying to identify potential intracellular targets. In later steps either membrane activity or the intracellular target can then be studied in detail. In our study,5 we decided to use membrane assays as a proof of concept for using “bioengineered bugs” as workhorses throughout peptide production and characterization. As described above we expressed the peptides recombinantly instead of chemically synthesizing them, and we also wanted to characterize their membrane activity based on recombinant bacteria. Therefore, assays involving artificial model membranes were not taken into consideration and only cell based assays probing the uptake of substances which do not penetrate intact bacterial membranes, were considered. Among the different methods we decided to use the method developed by Virta et al.50 because it was straight forward and compatible with the equipment already available to our workgroup. Briefly, this assay is based on a constitutively expressed insect luciferase which produces light only in presence of its substrate D-luciferin. At neutral pH externally added D-luciferin crosses the E. coli membranes very inefficiently until the membrane integrity is disturbed. This results in light peaks when pore-forming or membranolytic substances are added. We used the Envision Multilabel Plate Reader (PerkinElmer life and analytical sciences, Turku, Finland) which is designed for HTS measurements. However, for this kind of experiment it is not the optimal choice due to a “lag time” between sample addition and actual start of measurement, which is caused by plate handling and shaking inside the machine. For fast membrane acting AMPs like PolymyxinB, this results in loss of the light emission peak, since the measurement starts only after peak light emission has been reached (Fig. 1). The use of an optional dispenser unit would most likely resolve this problem. Even though we were able to successfully employ the method and are now using it as a standard procedure to quickly determine if compounds with unknown antimicrobial activity interfere with membrane integrity. For the future we are planning to include more bacterial whole-cell assays based on reporter gene fusions with luciferases and fluorescent proteins. Time will show if the combination of recombinant technology within both AMP production and characterization will become a success or not.

Figure 1.

Polymyxin B induces peak emission within the lag time of the luminescence reader. Perforation of the plasma membrane causes an influx of externally added D-luciferin into luciferase expressing E. coli cells and results in light emission measured as counts per second (cps). Light emission kinetics of E. coli cells treated with AMPs or water (solid line) at t = 0 is plotted as a function of time for 5 min starting 20 s after peptide addition. The lag time is due to plate handling and shaking inside the multi-plate-reader. This results in loss of peak activity for Polymyxin B (dotted line). Peak emission for Cecropin P1 (dashed line) at similar concentrations can be recorded. No peak in light emission is caused by the non-membrane active recombinant SpStrongylocin 1 (dash-dotted line). All AMPs were added at a final concentration of 5 µM.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/biobugs/article/11721

References

- 1.Bowdish DM, Davidson DJ, Hancock RE. A reevaluation of the role of host defence peptides in mammalian immunity. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2005;6:35–51. doi: 10.2174/1389203053027494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hancock RE, Brown KL, Mookherjee N. Host defence peptides from invertebrates—emerging antimicrobial strategies. Immunobiology. 2006;211:315–322. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang G, Li X, Wang Z. APD2: the updated antimicrobial peptide database and its application in peptide design. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:933–937. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mookherjee N, Hancock RE. Cationic host defence peptides: innate immune regulatory peptides as a novel approach for treating infections. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:922–933. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6475-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li C, Blencke HM, Smith LC, Karp MT, Stensvåg K. Two recombinant peptides, SpStrongylocins 1 and 2, from Strongylocentrotus purpuratus, show antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Dev Comp Immunol. 2010;34:286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li C, Haug T, Styrvold OB, Jorgensen TO, Stensvåg K. Strongylocins, novel antimicrobial peptides from the green sea urchin, Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis. Dev Comp Immunol. 2008;32:1430–1440. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boettner M, Prinz B, Holz C, Stahl U, Lang C. High-throughput screening for expression of heterologous proteins in the yeast Pichia pastoris. J Biotechnol. 2002;99:51–62. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(02)00157-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rashid F, Ali I, Sajid I, Elamin S, Yuan QP. Recombinant Expression of an Antimicrobial Peptide Hepcidin in Pichia pastoris. Pak J Zool. 2009;41:349–356. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang G, Liu T, Peng W, Sun X, Zhang H, Wu C, et al. Expression and localization of recombinant human EDG-1 receptors in Pichia pastoris. Biotechnol Lett. 2006;28:1581–1586. doi: 10.1007/s10529-006-9125-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holz C, Hesse O, Bolotina N, Stahl U, Lang C. A micro-scale process for high-throughput expression of cDNAs in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Protein Expr Purif. 2002;25:372–378. doi: 10.1016/s1046-5928(02)00029-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bordes F, Fudalej F, Dossat V, Nicaud JM, Marty A. A new recombinant protein expression system for high-throughput screening in the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. J Microbiol Methods. 2007;70:493–502. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith GE, Summers MD, Fraser MJ. Production of human beta interferon in insect cells infected with a baculovirus expression vector. Mol Cell Biol. 1983;3:2156–2165. doi: 10.1128/mcb.3.12.2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cui M, Li W, Liu W, Yang K, Pang Y, Haoran L. Production of recombinant orange-spotted grouper (Epinephelus coioides) luteinizing hormone in insect cells by the baculovirus expression system and its biological effect. Biol Reprod. 2007;76:74–84. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.050484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jordan KR, McMahan RH, Oh JZ, Pipeling MR, Pardoll DM, Kedl RM, et al. Baculovirus-infected insect cells expressing peptide-MHC complexes elicit protective antitumor immunity. J Immunol. 2008;180:188–197. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mancia F, Patel SD, Rajala MW, Scherer PE, Nemes A, Schieren I, et al. Optimization of protein production in mammalian cells with a coexpressed fluorescent marker. Structure. 2004;12:1355–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aricescu AR, Lu W, Jones EY. A time- and cost-efficient system for high-level protein production in mammalian cells. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:1243–1250. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906029799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morlot C, Hemrika W, Romijn RA, Gros P, Cusack S, McCarthy AA. Production of Slit2 LRR domains in mammalian cells for structural studies and the structure of human Slit2 domain 3. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2007;63:961–968. doi: 10.1107/S0907444907035470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caron AW, Nicolas C, Gaillet B, Ba I, Pinard M, Garnier A, et al. Fluorescent labeling in semi-solid medium for selection of mammalian cells secreting high-levels of recombinant proteins. BMC Biotechnol. 2009;9:42. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-9-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baneyx F. Recombinant protein expression in Escherichia coli. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1999;10:411–421. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(99)00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esposito D, Chatterjee DK. Enhancement of soluble protein expression through the use of fusion tags. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2006;17:353–358. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Destoumieux D, Bulet P, Strub JM, Van Dorsselaer A, Bachere E. Recombinant expression and range of activity of penaeidins, antimicrobial peptides from penaeid shrimp. Eur J Biochem. 1999;266:335–346. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carballar-Lejarazu R, Rodriguez MH, de la Cruz Hernandez-Hernandez F, Ramos-Castaneda J, Possani LD, Zurita-Ortega M, et al. Recombinant scorpine: a multifunctional antimicrobial peptide with activity against different pathogens. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:3081–3092. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8250-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiou MJ, Chen LK, Peng KC, Pan CY, Lin TL, Chen JY. Stable expression in a Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell line of bioactive recombinant chelonianin, which plays an important role in protecting fish against pathogenic infection. Dev Comp Immunol. 2009;33:117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morassutti C, De Amicis F, Skerlavaj B, Zanetti M, Marchetti S. Production of a recombinant antimicrobial peptide in transgenic plants using a modified VMA intein expression system. FEBS Lett. 2002;519:141–146. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02741-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haught C, Davis GD, Subramanian R, Jackson KW, Harrison RG. Recombinant production and purification of novel antisense antimicrobial peptide in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1998;57:55–61. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(19980105)57:1<55::aid-bit7>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang L, Ching CB, Jiang R, Leong SS. Production of bioactive human beta-defensin 5 and 6 in Escherichia coli by soluble fusion expression. Protein Expr Purif. 2008;61:168–174. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar TK, Yang PW, Lin SH, Wu CY, Lei B, Lo SJ, et al. Cloning, direct expression and purification of a snake venom cardiotoxin in Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;219:450–456. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moon JY, Henzler-Wildman KA, Ramamoorthy A. Expression and purification of a recombinant LL-37 from Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1758:1351–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piers KL, Brown MH, Hancock RE. Recombinant DNA procedures for producing small antimicrobial cationic peptides in bacteria. Gene. 1993;134:7–13. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang H, Yuan Q, Zhu Y, Ma R. Expression and preparation of recombinant hepcidin in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr Purif. 2005;41:409–416. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang L, Falla T, Wu M, Fidai S, Burian J, Kay W, Hancock RE. Determinants of recombinant production of antimicrobial cationic peptides and creation of peptide variants in bacteria. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;247:674–680. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miroux B, Walker JE. Over-production of proteins in Escherichia coli: mutant hosts that allow synthesis of some membrane proteins and globular proteins at high levels. J Mol Biol. 1996;260:289–298. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dumon-Seignovert L, Cariot G, Vuillard L. The toxicity of recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli: a comparison of overexpression in BL21(DE3), C41(DE3) and C43(DE3) Protein Expr Purif. 2004;37:203–206. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2004.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pruzinska A, Tanner G, Anders I, Roca M, Hortensteiner S. Chlorophyll breakdown: pheophorbide a oxygenase is a Rieske-type iron-sulfur protein, encoded by the accelerated cell death 1 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15259–15264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2036571100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kremer L, Nampoothiri KM, Lesjean S, Dover LG, Graham S, Betts J, et al. Biochemical characterization of acyl carrier protein (AcpM) and malonyl-CoA:AcpM transacylase (mtFabD), two major components of Mycobacterium tuberculosis fatty acid synthase II. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:27967–27974. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103687200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berthold DA, Stenmark P, Nordlund P. Screening for functional expression and overexpression of a family of diiron-containing interfacial membrane proteins using the univector recombination system. Protein Sci. 2003;12:124–134. doi: 10.1110/ps.0223703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong KB, DeDecker BS, Freund SM, Proctor MR, Bycroft M, Fersht AR. Hot-spot mutants of p53 core domain evince characteristic local structural changes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8438–8442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rajalingam K, Wunder C, Brinkmann V, Churin Y, Hekman M, Sievers C, et al. Prohibitin is required for Ras-induced Raf-MEK-ERK activation and epithelial cell migration. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:837–843. doi: 10.1038/ncb1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim HK, Chun DS, Kim JS, Yun CH, Lee JH, Hong SK, et al. Expression of the cationic antimicrobial peptide lactoferricin fused with the anionic peptide in Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;72:330–338. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee JH, Minn I, Park CB, Kim SC. Acidic peptide-mediated expression of the antimicrobial peptide buforin II as tandem repeats in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr Purif. 1998;12:53–60. doi: 10.1006/prep.1997.0814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skosyrev VS, Kulesskiy EA, Yakhnin LV, Temirov YV, Vinokurov LM. Expression of the recombinant antibacterial peptide sarcotoxin IA in Escherichia coli cells. Protein Expr Purif. 2003;28:350–356. doi: 10.1016/s1046-5928(02)00697-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skosyrev VS, Rudenko NV, Yakhnin AV, Zagranichny VE, Popova LI, Zakharov MV, et al. EGFP as a fusion partner for the expression and organic extraction of small polypeptides. Protein Expr Purif. 2003;27:55–62. doi: 10.1016/s1046-5928(02)00595-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee JH, Kim JH, Hwang SW, Lee WJ, Yoon HK, Lee HS, et al. High-level expression of antimicrobial peptide mediated by a fusion partner reinforcing formation of inclusion bodies. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;277:575–580. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pietiainen M, Francois P, Hyyrylainen HL, Tangomo M, Sass V, Sahl HG, et al. Transcriptome analysis of the responses of Staphylococcus aureus to antimicrobial peptides and characterization of the roles of vraDE and vraSR in antimicrobial resistance. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:429. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tomasinsig L, Scocchi M, Mettulio R, Zanetti M. Genome-wide transcriptional profiling of the Escherichia coli response to a proline-rich antimicrobial peptide. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:3260–3267. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.9.3260-3267.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vollmer AC, Belkin S, Smulski DR, Van Dyk TK, LaRossa RA. Detection of DNA damage by use of Escherichia coli carrying recA'::lux, uvrA'::lux, or alkA'::lux reporter plasmids. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2566–2571. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.7.2566-2571.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galluzzi L, Karp M. Amplified detection of transcriptional and translational inhibitors in bioluminescent Escherichia coli K-12. J Biomol Screen. 2003;8:340–346. doi: 10.1177/1087057103008003012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anko ML, Kurittu J, Karp M. An Escherichia coli biosensor strain for amplified and high throughput detection of antimicrobial agents. J Biomol Screen. 2002;7:119–125. doi: 10.1177/108705710200700204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lampinen J, Virta M, Karp M. Use of Controlled Luciferase Expression To Monitor Chemicals Affecting Protein Synthesis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2981–2989. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.8.2981-2989.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Virta M, Akerman KE, Saviranta P, Oker-Blom C, Karp MT. Real-time measurement of cell permeabilization with low-molecular-weight membranolytic agents. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;36:303–315. doi: 10.1093/jac/36.2.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brogden KA. Antimicrobial peptides: pore formers or metabolic inhibitors in bacteria? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:238–250. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]