Abstract

Listeria monocytogenes is an intracellular pathogen that lyses the phagosomal vacuole of infected cells, proliferates in the host cell cytoplasm and can actively enter adjacent cells. The pathogen is therefore well suited to exploitation as a vector for the delivery of DNA to target cells as the lifecycle favors cellular targeting with vector amplification and the potential for cell-to-cell spread. We have recently demonstrated DNA transfer by L. monocytogenes in growing tumors in murine models. Our approach exploited an ampicillin sensitive stain of L. monocytogenes which can be lysed through systemic administration of ampicillin to facilitate release of plasmid DNA for expression by infected mammalian cells. Here, we discuss the implications of this technology and the potential for future improvements of the system.

Key words: bactofection, Listeria monocytogenes, salmonella, tumor, tumor, cancer, gene delivery, luminescence, therapy

Bacteria and DNA Delivery

Bacteria-mediated transfer of plasmid DNA into mammalian cells (bactofection) has been shown to have potential as a novel approach to express heterologous proteins in different cell types.1,2 Delivery of genetic material is achieved through entry of the entire bacterium into target cells. L. monocytogenes is particularly efficient in mediating internalization into host cells and once inside cells the bacterium produces specific virulence factors which lyse the vacuolar membrane and allow escape into the cytoplasm.3 In the cytosol, L. monocytogenes is capable of actin-based motility and cell-to-cell spread without an extracellular phase.3 Arguably the pathogen has greater potential for exploitation than other proposed vectors (such as Salmonella spp. or E. coli) which remain trapped in the target cell phagosome.

The work of Dietrich et al.4 demonstrated that L. monocytogenes can deliver DNA to tumor cells in vitro. This system utilised a novel approach whereby the host strain expressed a phage lysin from the Listerial actA promoter when the strain entered the host cell cytoplasm. Thus the vector demonstrated autolysis in the target cell cytoplasm followed by release of the DNA, entry of DNA into the nucleus and expression by the eukaryotic machinery. The system was further refined through the demonstration that L. monocytogenes can also be used to deliver RNA to host cells, thereby bypassing the requirement for the rate limiting step of plasmid access to the host cell nucleus.5

We recently provided the first evidence that L. monocytogenes can deliver DNA to tumors in vivo in mice and also ex vivo in resected human breast tumor tissue.6 We generated a highly ampicillin sensitive host strain of L. monocytogenes which was capable of growth in solid tumors in mice but was rapidly lysed following administration of ampicillin (Fig. 1). This was engineered to carry a plasmid in which the firefly luciferase gene was cloned downstream of the eukaryotic CMV promoter. We also incorporated a phage lysin into the system under the transcriptional control of the same promoter so that following expression by the host cell, phage lysin will aid in further lysis of other remaining cytoplasmic vector. Figure 2 highlights the protocol and shows the timeline from introduction of L. monocytogenes vector into the tumor, followed by a period of vector replication and then lysis of the vector and subsequent host cell expression of the delivered DNA. For these experiments we utilised nude mice bearing human MCF-7 breast xenografts, as human epithelial cells are most efficiently invaded by L. monocytogenes.3 In this model, administration of ampicillin promoted successful DNA delivery (Fig. 3) but was insufficient to completely eliminate the bacterium in the nude mouse model until used in combination with moxifloxacin. It is known that single antibiotics administered in isolation are ineffective in controlling listeriosis, and currently the reference treatment in humans is based on synergistic combinations such as ampicillin and gentamicin administrated intravenously.7 It has recently been shown in murine models that inclusion of one of the newer fluoroquinolones such as moxifloxacin can improve efficacy, being commercially available and highly effective against intracellular and extracellular listeria.8 We are currently investigating whether more effective elimination of the vector occurs when similar experiments are conducted in immunocompetent mice.

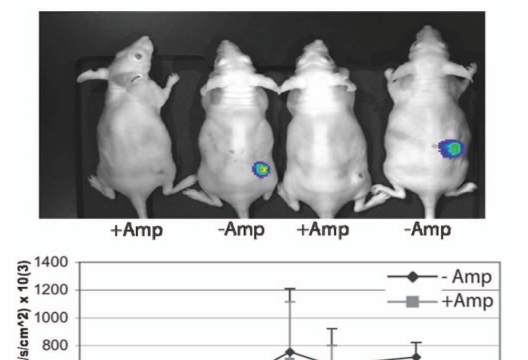

Figure 1.

L. monocytogenes efficiently infects human tumors in vivo and is controlled by ampicillin treatment. Human epithelial colon carcinoma tumors (Caco-2) growing in MF1-nu/nu athymic mice were directly administered 104 L. monocytogenes lux in a 100 µl injection. Luminescence was followed over time by 2D IVIS imaging. Bacteria were seen to proliferate over time, specifically in tumor, with no spread to liver or spleen observed following intratumoral injection. Animals remained healthy through the experiment, with no evidence of listeriosis. Systemic (i.p.) administration of 10 µg ampicillin on days 6 and 7 post Listeria injection resulted in complete elimination of bacterial lux expression by day 8, indicating mammalian cellular entry of antibiotic and bacteriocidal action.

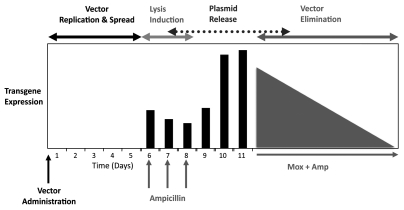

Figure 2.

Treatment regimen for controllable L. monocytogenes bactofection. Schematic representation of the timeline for L. monocytogenes vector administration followed by phases of amplification and intratumoral spread, lysis and plasmid release, and systemic bacterial vector elimination when desired by combined treatment with Moxifloxacin and Ampicillin.

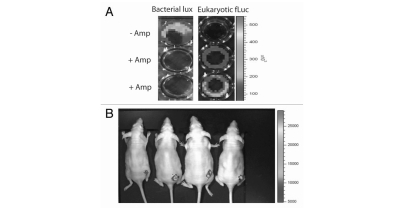

Figure 3.

Ampicillin-mediated lysis of LMO and plasmid release. (A) In vitro invasion assays with LMO and MCF-7 cells confirmed that bacteria are lysed by ampicillin facilitating plasmid release with subsequent firefly luciferase (fLuc)-derived luminescence upon exposure to luciferin substrate. (B) Firefly luciferase expression from MCF-7 tumors directly administered 106 L. monocytogenes, followed 6 days later by i.p. administration of 100 mg/ml ampicillin for 3 days. Ampicillin treatment therefore serves to (i) lyse bacteria to facilitate plasmid delivery and (ii) limit Listeria infection.

Given the heterogeneity of cell types within tumors (including stromal cells, endothelial cells and immune cells in addition to malignant tumor cells), we utilised anti-Luc antibody staining and flow cytometry to investigate the nature of cells targeted by our bactofection system. Analyses revealed that 69% of cells expressing luciferase were epithelial in origin, whilst no macrophage cells were positive for luciferase expression at 9 days post administration. This indicates that epithelial cells in the solid tumors were targeted by gene delivery and that the system has potential for delivery of therapeutic gene systems, especially since the majority of cancers are epithelial in origin. Indeed we have recently instigated HSVtk/glancyclovir pro-drug therapy of tumors involving bactofection of tumors with Listeria carrying a CMV-HSVtk plasmid, and preliminary data demonstrate promising results (manuscript in preparation). Intratumoral administration of the vector resulted in plasmid delivery and measurable tumor regression.

Route of Administration

Many bacteria, including Listeria, have the potential to grow preferentially in tumor tissue when inoculated systemically into tumor-bearing mice.1,9–11 However in the proof-of-concept bactofection experiments outlined we administered the inoculum directly into the murine tumors. It is clear that for further development of the system future work will need to establish whether systemic (intravenous) inoculation will be sufficient to selectively seed tumors, both primary and metastases, with the vector and to permit bactofection. Given that the pathogen has the capacity to cross the gastrointestinal tract it may also be possible to administer the vector orally in order to deliver DNA to solid tumors. However, given the poor uptake of L. monocytogenes in the murine model (relative to humans) this will have to be tested in transgenic (humanized) mice or using ‘murinized’ L. monocytogenes strains.12,13 L. monocytogenes targets epithelial cells through the interaction of the bacterial protein InlA with host cell E-cadherin. The organism can engage human E-cadherin but not mouse E-cadherin due to sequence variation.12 Wollert et al. have recently developed a murinized strain with significantly enhanced invasive ability in mice, through amino acid modifications in InlA.13 Use of murinized strains will thus permit experimentation in immunocompetent mice.

The Balance between Safety and Efficacy

In order to develop an efficient gene medicine, it is clear that certain improvements to our system are required. In order to allow for human intervention studies, safety of the system is of paramount importance. It is significant that Maciag and co-workers recently performed Phase I trials in human subjects with cervical cancer and demonstrated the safety of an attenuated L. monocytogenes protein delivery vector in a vaccine setting.14 The company behind that work (Advaxis Inc.,) is dedicated to the development of Listeria-based cancer vaccination strategies. The L. monocytogenes mutant they developed is deficient in PrfA (the global regulator of virulence gene expression) and is highly attenuated, yet retains in vivo immunogenicity. We are conscious of the fact that one of the benefits of our system is the ability of the vector to spread from cell-to-cell within the tumor mass. Attenuation through mutation of classical virulence factors would therefore affect the efficacy of our system. It is likely that other approaches, such as the creation of auxotrophic mutants, as described by others,15,16 will have to be implemented when developing L. monocytogenes bactofection vehicles so as to retain intracellular growth and cell spread but limit virulence for the host. It will be a challenge to select the correct mutant strain to provide an adequate level of vector amplification in vivo whilst maintaining a significant degree of attenuation to ensure safety.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/biobugs/article/11725

References

- 1.Vassaux G, Nitcheu J, Jezzard S, Lemoine NR. Bacterial gene therapy strategies. J Pathol. 2006;208:290–298. doi: 10.1002/path.1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tangney M, Gahan CG. Listeria monocytogenes as a Vector for Anti-Cancer. Therapies. 2010;10:46–55. doi: 10.2174/156652310790945539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamon M, Bierne H, Cossart P. Listeria monocytogenes: a multifaceted model. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:423–434. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dietrich G, Bubert A, Gentschev I, Sokolovic Z, Simm A, Catic A, et al. Delivery of antigen-encoding plasmid DNA into the cytosol of macrophages by attenuated suicide Listeria monocytogenes. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:181–185. doi: 10.1038/nbt0298-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schoen C, Kolb-Maurer A, Geginat G, Loffler D, Bergmann B, Stritzker J, et al. Bacterial delivery of functional messenger RNA to mammalian cells. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:709–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Pijkeren JP, Morrissey D, Monk IR, Cronin M, Rajendran S, O'sullivan GC, et al. A novel Listeria monocytogenes-based DNA delivery system for cancer gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther. 2010;21:405–416. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hof H. An update on the medical management of listeriosis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5:1727–1735. doi: 10.1517/14656566.5.8.1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grayo S, Join-Lambert O, Desroches MC, Le Monnier A. Comparison of the in vitro efficacies of moxifloxacin and amoxicillin against Listeria monocytogenes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:1697–1702. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01211-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujimori M, Amano J, Taniguchi S. The genus Bifidobacterium for cancer gene therapy. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2002;5:200–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu YA, Shabahang S, Timiryasova TM, Zhang Q, Beltz R, Gentschev I, et al. Visualization of tumors and metastases in live animals with bacteria and vaccinia virus encoding light-emitting proteins. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:313–320. doi: 10.1038/nbt937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei MQ, Mengesha A, Good D, Anne J. Bacterial targeted tumour therapy-dawn of a new era. Cancer Lett. 2008;259:16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lecuit M, Vandormael-Pournin S, Lefort J, Huerre M, Gounon P, Dupuy C, et al. A transgenic model for listeriosis: role of internalin in crossing the intestinal barrier. Science. 2001;292:1722–1725. doi: 10.1126/science.1059852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wollert T, Pasche B, Rochon M, Deppenmeier S, van den Heuvel J, Gruber AD, et al. Extending the host range of Listeria monocytogenes by rational protein design. Cell. 2007;129:891–902. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maciag PC, Radulovic S, Rothman J. The first clinical use of a live-attenuated Listeria monocytogenes vaccine: a Phase I safety study of Lm-LLO-E7 in patients with advanced carcinoma of the cervix. Vaccine. 2009;27:3975–3983. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gahan CG, Collins JK. Vaccination of mice with attenuated mutants of Listeria monocytogenes: requirement for induction of macrophage la expression. Microb Pathog. 1995;18:417–422. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1995.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stritzker J, Janda J, Schoen C, Taupp M, Pilgrim S, Gentschev I, et al. Growth, virulence and immunogenicity of Listeria monocytogenes aro mutants. Infect Immun. 2004;72:5622–5629. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.10.5622-5629.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]