Abstract

Graphene is emerging as an interesting electronic material for future electronics due to its exceptionally high carrier mobility and single-atomic thickness. Graphene-dielectric integration is of critical importance for the development of graphene transistors and a new generation of graphene based electronics. Deposition of dielectric materials onto graphene is of significant challenge due to the intrinsic material incompatibility between pristine graphene and dielectric oxide materials. Here we review various strategies being researched for graphene-dielectric integration. Physical vapor deposition (PVD) can be used to directly deposit dielectric materials on graphene, but often introduces significant defects into the monolayer of carbon lattice; Atomic layer deposition (ALD) process has also been explored to to deposit high-κ dielectrics on graphene, which however requires functionalization of graphene surface with reactive groups, inevitably leading to a significant degradation in carrier mobilities; Using naturally oxidized thin aluminum or polymer as buffer layer for dielectric deposition can mitigate the damages to graphene lattice and improve the carrier mobility of the resulted top-gated transistors; Lastly, a physical assembly approach has recently been explored to integrate dielectric nanostructures with graphene without introducing any appreciable defects, and enabled top-gated graphene transistors with the highest carrier mobility reported to date. We will conclude with a brief summary and perspective on future opportunities.

Keywords: semiconductor, graphene, transistor, dielectrics, nanowires, nanoribbons

1. Introduction: the promise and challenges for graphene electronics

1.1 The promise of graphene electronics

Graphene is a one-atom-thick planar sheet of sp2-bonded carbon atoms arranged in a honeycomb crystal lattice (Fig. 1a and b) [1, 2]. Graphene has attracted considerable interest in the past several years due to its significant potential for both the fundamental studies and technological applications [3–21]. Graphene is characterized by a linear dispersion relation with the Dirac point separating the valence and conduction bands with a zero bandgap, which limits the achievable on-off current ratios but does not rule out analogue radio frequency (RF) device applications. In particular, it has been demonstrated that graphene exhibits the highest carrier mobilities exceeding 200,000 cm2/V·s [11], which is not only ~100 times greater than that of silicon but also about 10 times better than the state-of-the-art high mobility semiconductors lattice-matched to indium phosphide. Along with many other desirable properties, including large critical current densities (~2×108 A/cm2) [22], a high saturation velocity (5.5 X 107 cm/s) [23], and a micrometer-scale mean free path at room temperature, graphene is currently regarded as a highly promising materials for high-speed electronics [23–28]. These desirable properties promise graphene to offer excellent short-circuit current-gain cutoff frequency (fT) and for high frequency applications. In particular, it has been recently demonstrated that high speed graphene devices were achieved with a cutoff frequency fT reaching up to 100 GHz, demonstrating the significant potential of graphene devices for radio frequency (RF) applications (Fig. 1c and d) [25].

Fig. 1.

Graphene as a potential electronic material. (a) Schematic illustration of graphene as an atomic-scale honeycomb lattice of carbon atoms. (b) TEM image of graphene, adapted from [2]. (c) Image of radio frequency devices fabricated on a 2-inch graphene wafer and schematic cross-sectional view of a top-gated graphene FET. (d) Measured small-signal current gain |h21| as a function of frequency f for a 240-nm-gate and a 550-nm-gate graphene FET at VD = 2.5 V. Cutoff frequencies, fT, were 53 and 100 GHz for the 550-nm and 240-nm devices, respectively. Adapted from [25].

Due to the zero-band-gap nature, bulk graphene remains highly conductive even at the charge neutrality point, and therefore cannot be used for effective field-effect transistors (FETs) at room temperature for digital applications. The formation of graphene nanostructures with lateral quantum confinement can open up a finite band gap to enable room temperature FET operation (Fig. 2) [10, 29–37]. It has been demonstrated that sub-10 nm graphene nanoribbons (GNRs) can be created, and used to fabricate FETs that can be effectively switched off at room temperature [31, 32]. We have recently developed a rational approach to fabricate GNRs with controllable widths from 6–20 nm using chemical synthesized nanowires as the physical etch masks [35]. Importantly, using such GNR as the semiconducting channel, we have fabricated room temperature FETs with on-off ratios >100 (Fig. 2a). It has also been demonstrated that graphene nanomesh, as a mimick of graphene nanoribbon networks, can effectively introduce a finite conduction band gap into the two-dimensional graphene to enable room temperature transistors with comparable on/off ratios (Fig. 2b) [34].

Fig. 2.

Graphene nanostructures for the opening of a conduction gap in graphene.. (a) Schematic view of a graphene nanoribbon and transfer characteristics of a grapnene nanoribbon transistor with on/off ratio >100. (c) Schematic view of a graphene nanomesh and transfer characteristics of a grapnene nanoribbon transistor with on/off ratio >100. Adapted from [34] and [35].

1.2 Graphene dielectric integration and its impact on transistor performance

The gate dielectric is an essential component of a transistor. Compared to the semiconductor channel, the gate dielectrics have received much less attention due to the relative uninteresting nature of an insulator, despite its significant impact on the critical device parameters including transconductance, subthreshold swing and frequency response. Among the various strategies explored to fabricate graphene or graphene nanostructure based FETs, most efforts employ a silicon substrate as a global back gate and a 300 nm thick silicon dioxide (SiO2) as the gate dielectrics. This substrate is used primarily because the graphene can be readily visualized using optical microscope on this particular substrate due to optical interference [38–42]. The readily viewable graphene on the 300 nm SiO2 substrate has allowed easy device fabrication and led to many interesting scientific discoveries. The requirement of 300 nm SiO2, however, can intrinsically limit the resulted device performance in several perspectives. First, optical detection technique to visualize graphene has been demonstrated and widely used for a SiO2 thickness of 300 nm, but a 5% variation in thickness (e.g. to 315 nm) can significantly lower the contrast [40]. Second, the devices made on 300 nm SiO2 substrate have small gate capacitance due to the relatively large dielectric thickness and the small dielectric constant, and thus require high switching voltage [43].

Exploring high-κ dielectric substrate may mitigate these problems [43, 44]. For example, we have demonstrated that 72 nm Al2O3/Si substrate is superior to the 300 nm SiO2/Si substrate for both the visualization of graphene and improve the transistor performance [43]. Compared to the 300 nm SiO2/Si substrate, the 72 nm Al2O3/Si substrate can enhance the optical contrast of single layer graphene by at least 3 times. Furthermore, using the Al2O3 film as the gate dielectrics, the back-gated graphene FETs have been fabricated to exhibit more than 7-fold increase in transconductance.

It is important to note that the carrier mobility of the resulting graphene transistors can be significant impacted by the nature of the dielectric layer and graphene-dielectric interface. Theoretical studies suggest that the intrinsic mobility of graphene, set by longitudinal acoustic (LA) phonon scattering, can reach 105 cm2V−1s−1 at room temperature [45]. However, the achievable carrier mobility in an actual device can often be limited by extrinsic scattering sources, many of which arise from the surface morphology, chemistry, structural, and electronic properties of the substrate. For example, recent calculation suggests that a mobility as high as 44,000 cm2V−1s−1 can be achieved in graphene on SiO2/Si substrate at room temperature, which is limited by the phonon scattering [45–48]. Experimental studies have demonstrated that mobility values in the range of 2 – 20 × 103 cm2V−1s−1 for the graphene transistor made on SiO2/Si substrate [49]. The variability in mobility is attributed to various degrees of local disorder in graphene and in the dielectric substrate.

Increasing the mobility beyond the extrinsic limits is one of the central challenges of the graphene community. Recently, two groups have reported a significant improvement in the mobility of suspended graphene after current-heating annealing [12, 50]. However, a more device friendly solution may rely on placing graphene on a different substrate. Several alternatives have been explored, however, the mobility obtained so far is comparable to that on SiO2 [51]. Utilization of high-κ dielectric material as the gate insulator is expected to partially screen charged impurities and enhance the carrier mobility [48]. A recent report demonstrate significant carrier mobility improvement to 7 × 104 cm2V−1s−1 in graphene transistors using single-crystal epitaxial PbZr0:2Ti0:8O3 (PZT) films as the gate oxide [44]. This remarkable improvement was attributed to the strong screening of PZT film and possible ordered adsorbate molecular layer at interface that may reduce the scattering [52].

On the other hand, most studies of graphene transistors discussed above employ a silicon substrate as a global back gate, which, although useful for fundamental investigations, will be of limited use for practical applications due to the inability to independently address multiple devices on the same chip. Top-gated devices can readily allow independently addressable device arrays and functional circuits, and therefore are of significant interest [53–55]. The formation of top-gated graphene transistors requires direct deposition of dielectric oxide material on top of pristine graphene, which is of significant challenge due to the intrinsic incompatibility between these two types of materials. Deposition of oxide dielectrics onto graphene for top-gated transistors can often introduce substantial defects into graphene lattice and lead to significant degradation in carrier mobilities [23, 27, 56–61]. Here we review various strategies, including physical vapour deposition (PVD), atomic layer deposition (ALD) and physical assembly approach, for graphene-dielectric integration for top-gated graphene transistors, discussing the potential merits and challenges of each.

2. Physical vapor deposition of top-gate dielectrics on graphene

Physical vapour deposition (PVD) such as electron-beam evaporation or sputtering process is a common approach to deposit a variety of oxide dielectric thin films on many different substrates including graphene. However, the PVD process usually yields lower quality dielectrics and can cause significant damages to graphene.

2.1 Raman characterization of graphene-dielectric integration by PVD

Raman spectroscopy has been used to study the interaction between single layer graphene and PVD dielectrics (Fig. 3) [62]. Various PVD approaches, including electron beam evaporation, pulsed laser deposition (PLD) and radio frequency (RF) sputter, were explored to deposit SiO2 layer on graphene. Raman spectra of the graphene covered with these PVD SiO2 layers all show large defect band (D-band), indicating substantial defects introduced into the graphene lattice. Strong defect-induced D band was also observed in Raman spectra of graphene covered with PLD deposited HfO2. In contrast, simple spin coating of polymer dielectric such as polymethyl methacrylate does not introduce D-band. These results clearly demonstrate that PVD process can result in significant damage to carbon lattice, and simple spin coating would not introduce obvious defects.

Fig. 3.

Raman spectra of the graphene show a clear defect band emerging at 1350 cm−1 after PVD dielectric deposition using various approaches, suggesting significant defects are introduced into graphene lattice during the dielectric deposition process. Adapted from [62].

2.2 Top-gated graphene transistors using PVD dielectrics

The PVD dielectric film can be used as top-gate dielectrics for graphene transistors. However, due to the significant damage the process can cause, the mobility values observed in the top-gated devices fabricated from this process are typically nearly one order of magnitude smaller than what can be achieved in the back-gated devices. For example, Lemme et al. reported the top-gated graphene transistor, in which electron-beam evaporated SiO2 was used as top gate dielectrics [58]. Before the deposition of the top-gate dielectrics, the charge carrier mobilities in the uncovered graphene are estimated to be μh = 4790 cm2V−1s−1 and μe = 4780 cm2V−1s−1. In stark contrast, the room temperature mobility values are severely degraded to μh = 710 cm2V−1s−1 and μe = 530 cm2V−1s−1 after the deposition of the SiO2 (Fig. 4). This study highlights that the PVD deposited dielectric layer can significantly disrupt the charge transport characteristics in graphene.

Fig. 4.

(a) SEM image of a graphene transistor with PVD top-gate dielectrics. (b) Back-gate transfer characteristics of Graphene-FET with and without a top gate. Adapted from [58].

3. Atomic layer deposition of top-gate dielectrics on graphene

Atomic layer deposition (ALD) is a well developed approach for growing high-κ gate dielectric layers, owing to its precise control over the film thickness and uniformity [63]. However, the direct deposition of high-κ dielectric materials, such as Al2O3 and HfO2, on graphene using H2O-based ALD is not possible because of the hydrophobic nature of graphene basal plane [64] and the lack of functional groups for molecular absorption which is necessary for ALD.

3.1 Challenges in direct ALD of top-gated dielectrics on graphene

The attempt to directly deposit oxide dielectrics on pristine graphene using ALD failed to produce continuous layer of dielectrics. Given that a perfect graphite surface is chemically inert [65], attempts to grow ALD Al2O3 layer on a clean highly oriented pyrolytic graphite surface lead to only a selective growth at the steps between graphite layers, where the broken carbon bonds along the terraces serve as one-dimensional nucleation center for the initial ALD process [66]. Fig. 54a,b shows AFM images of the same area before and after ALD of ~2 nm Al2O3. Before ALD, the height of the triangular graphene piece at the bottom and the large piece on the left was ~1.7 and ~2.0 nm, respectively. Near the edge of the graphene, there was also a narrow ~1.0 nm high stripe. After ALD, ~2.0 nm Al2O3 was coated on SiO2; The apparent topography height of the three graphene sheets was obviously reduced to a level similar to that of the ALD-coated SiO2. The height difference before and after ALD suggests that no Al2O3 was effectively coat on pristine graphene sheets. This is because ALD relies on chemisorption and rapid reaction of precursor molecules with surface functional groups [67, 68]. As a result, no ALD can occur on the pristine graphene plane since it does not have any dangling bonds or surface functional groups to react with the precursors. Interestingly, quasicontinuous bright lines of Al2O3 preferentially grown on the edges of graphene sheets, suggesting dangling bonds on the edges or possible termination by −OH or other reactive species. Some bright dots in the middle of graphene sheets may correspond to ALD Al2O3 island around the defects such as pentagon-hexagon pairs or vacancies known to exist in graphite [69].

The unsuccessful ALD attempt to deposit oxide dielectrics on graphene calls for additional surface functionalization to create functional groups for oxide nucleation. The key idea enabling the high-κ dielectric layer growth on graphene by ALD is to provide intentional nucleation sites on the inert surface of graphene. To this end, Lin et al. have used a functionalization layer consisting of 50 cycles of NO2-TMA (trimethylaluminum) in ALD process prior to the growth of gate oxide. This NO2-TMA functionalization layer was essential for the ALD process and allows to achieve a uniform thin (<10 nm) coating of oxide dielectrics on graphene without producing pinholes [70]. The dielectric constant of ALD-grown Al2O3 in this way was determined to be about 7.5 by capacitance-voltage measurements.

Top-gated graphene transistors have also been fabricated using dielectric deposited with this method [27]. Fig. 6a and b shows an schematic view and SEM image of the device with the e-beam lithography defined Ti/Au (1 nm/50 nm) thin film as the source and drain electrodes, a 12 nm thick Al2O3 layer was then deposited by ALD at 250 °C as the gate insulator, and Pd/Au (10 nm/50 nm) thin film the top gate. DC electrical characterization was conducted to determine the device performance. Fig. 6c shows the conductance, G = ID/VD, of a graphene device before ALD oxide deposition using the silicon substrate as the back gate and a DC source-drain bias VD of 100 mV, and the inset of Fig. 6c shows the transfer characteristics after ALD oxide deposition. Based on these plot, it is evident that there was significant reduction in both the device conductance and field-effect mobility after the deposition of top gate dielectrics by ALD. The current and mobility degradation in the oxide-covered devices may be attributed to charged impurity scattering associated with the NO2 functionalization layer and interface phonon scattering in the oxide [45]. Other similar attempts by using O3 functionalization [64], or simply nucleating the dielectric growth from impurities on graphene without prior cleaning [23] has resulted in devices with significant degradation in carrier mobility. These results indicate that further optimization or alternative dielectrics deposition method are required in order to retain the high intrinsic mobilities in graphene [71, 72].

Fig. 6.

(a) (False color) scanning electron microscopy image of the graphene channel and contacts. The inset shows the optical image of the as-deposited graphene flake (circled area) prior to the formation of electrodes. (b) Schematic cross section of the graphene transistor. Note that the device consists of two parallel channels controlled by a single gate in order to increase the drive current and device transconductance. (c) Measured conductance as a function of back-gate voltage, VBG, of the graphene transistor before depositing the top-gate dielectric. The inset shows the same device after the deposition of Al2O3 by ALD. The two arrows represent the sweeping direction of the gate voltage. Adapted from [27].

3.2 Molecular buffer layer for ALD deposition of oxide dielectrics on graphene

The functioning of graphene surface for ALD growth of oxide will inevitably break the chemical bonds in the graphene lattice, leading to severe degradation in the electronic performance of the graphene devices. To mitigate this problem, various buffer layers have been introduced to help the nucleation and growth of the oxide dielectrics on graphene and at the same time minimizes the potential damage to the carbon lattice.

Wang et al. carried out the initial studies to investigate the ALD deposition of dielectrics on graphene using a molecular buffer/nucleation layer [73]. In their studies, the mechanical peeled graphene sheets were soaked in 3,4,9,10-perylene tetracarboxylic acid (PTCA) solution for ~30 min, thoroughly rinsed, and blown dry. The chip was immediately loaded into the ALD chamber to prevent contamination by molecules in the air. The deposition of Al2O3 film was carried out at ~100 °C using trimethylaluminum and water as the precursors [74]. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) imaging was used to characterize the few-layer graphene sheets and their integration with graphene.

The PTCA-treatment of the sample introduces a high density of carboxylate-terminated perylene molecules and achieves densely packed functional groups to allow ALD deposition of continuous uniform layer of ultrathin Al2O3 on graphene (Fig. 7a). Fig. 7b,c shows AFM images of the same area before and after deposition of ~2 nm Al2O3. Before ALD, the height of the graphene under the line cut was ~1.6 nm, which increased to ~3.0 nm after ALD. The relative height increase of Al2O3 -coated graphene was partly attributed to the thickness of PTCA layer, which was usually ~0.5–0.8 nm observed by AFM after PTCA coating step. The actual Al2O3 on graphene was ~2.8 ± 0.2 nm thick in Fig. 7c. AFM images show continuous coverage of dielectric layer on the entire graphene area with a root of mean square roughness of the Al2O3 film on graphene about 0.33 nm, suggesting the uniform packing of the underlayer PTCA molecules. Previous high vacuum STM studies have confirmed two modes of epitaxial packing of the PTCA precursor, perylene tetracarboxic dianhydride, along the lattice lines of highly oriented pyrolytic graphite [75, 76]. As the partitioning of PTCA from methanol to the graphene interface is highly favorable, it is likely that similar epitaxial packing is occurring in the solution phase, yielding dense, uniform coating on graphene. This self-assembled PTCA layer on graphene is responsible for uniform Al2O3 film coating. The noncovalent functionalization method is not destructive to graphene lattices and can be used for depositing ultrathin high-κ dielectrics for future graphene electronics [27].

Fig. 7.

ALD of Al2O3 on PTCA-coated graphene. (a) Schematic illustration of perylene tetracarboxylic acid (PTCA)-coated graphene. PTCA selectively adheres to graphene on SiO2 surfaces, providing binding sites for TMA deposition. Inset is a top view of PTCA structure. (b) AFM image of graphene on SiO2 before ALD. The height of the triangular shaped graphene is ~1.6 nm as shown in the height profile along the dashed line cut. Scale bar is 500 nm. (c) AFM image of the same area as (a) after ~2 nm Al2O3 ALD deposition. The height of the triangular shaped graphene becomes ~ 3.0 nm as shown in the height profile along the dashed line cut. Scale bar is 500 nm. (d) and (e) Schematics of graphene on SiO2 before and after ALD. The Al2O3 grows uniformly on noncovalently PTCA-coated graphene. Adapted from [73]

3.3 Metal oxide buffer layer for ALD of dielectrics on graphene

An alternative buffer layer is oxidized metal thin film. In this approach, a very thin layer of metal film is first deposited on graphene and allowed to oxidize to form a thin oxide layer, which can function as the nucleation layer for subsequent oxide deposition by ALD. For example, Kim et al. introduced a thin nucleation layer of oxidized aluminum between the graphene layer and the Al2O3 dielectric [77]. Prior to the Al2O3 layer growth by ALD, a 1–2 nm thick aluminum layer was deposited on the graphene surface by e-beam evaporation. This aluminum nucleation layer is completely oxidized as soon as the sample is exposed in air before transferring into ALD chamber [78, 79]. The samples were transferred to the ALD chamber for the deposition of Al2O3 using trimethylaluminum as the aluminum source and H2O as oxidizer. Initial stage of ALD growth starts with an H2O oxidizing cycle at elevated temperatures to ensure the complete oxidation of aluminum.

Top-gated graphene transistors have been fabricated to test the dielectric quality and its impact on the graphene devices. To fabricate the device, nickel thin film as the source and drain electrodes were first defined using electron beam lithography on mechanically peeled graphene, followed by an annealing step in a hydrogen atmosphere at 200 °C to remove possible contaminants such as resist residues [80]. Al nucleation layer was then deposited by high vacuum e-beam evaporator. The sample was then exposed in air and transferred into the ALD chamber and go through 167 cycles of Al2O3 deposition, resulting in a 15 nm thick Al2O3 film deposition. A 50 nm thick nickel top-gate electrode was subsequently fabricated to obtain the final device (Fig. 8a,b).

Fig. 8.

(a) Schematic of dual-gated graphene FET structure. (b) Optical microscope image of a graphene FET. (c) Rtot vs. VTG data measured at different VBG values. The inset shows the position of VDirac,TG at different VBG. Optical microscope image of a graphene FET. Adapted from [77].

The electrical transport characterizations were conducted at room temperature in a vacuum probe station. The top-gate electrode and the silicon substrate are used as a local gate and global back-gate, respectively, to control the carrier concentration and polarity in the graphene layer. Fig. 8c shows the total device resistance (Rtot) as a function of top-gate voltage measured at different back-gate biases from − 40 to 40 V and a drain bias of VD = 0.1 V. At VBG = 0 V, the sample resistance reaches a maximum (Dirac point) at VDirac,TG = 0.08 V. This observation indicates that there is little unintentional doping of the graphene sample after the top-gate stack deposition. As |VTG-VDirac,TG| increases, the electron or hole concentration in the graphene channel increases and Rtot decreases, resulting in V-shaped traces. Importantly, the top-gated device shows a very small hysteresis less than 0.05 V, and low leakage current less than 0.75 pA/μm2 through the Al2O3 dielectric, highlighting a high dielectric quality and a low interface state density.

The Rtot versus VTG measured at different VBG values shows an applied VBG bias changes the position of the Dirac point and also shifts vertically the measured resistance values (Fig 8c). The change in the Dirac point position can be explained as follows: a positive (negative) VBG bias induces a finite concentration of electrons (holes) in the active area, which is proportional to the back-gate capacitance (CBG). In order to restore the device to the Dirac point, where the carrier concentration is minimum, a negative (positive) applied VTG is required. The vertical shift is caused by the resistance change in the un-top-gated regions of the graphene flake. The shift of the top-gate Dirac points as a function of VBG can be used to determine top-gate and back-gate capacitances, CTG/CBG ~ 28 (inset of Fig. 8c). Using the back-gate capacitance value of CBG=11 nF/cm2, the top-gate capacitance can be estimated to be CTG=306 nF/cm2, corresponding to a relative dielectric constant of 6.0 for the Al2O3 film.

To determine the impact of the dielectric deposition, it is important to determine the carrier mobility. To accurately derive the mobility value, the contact resistance should be carefully excluded as it is comparable to the graphene transistor channel resistance. The authors have adopted a model to exclude the impact of the contact resistance as detailed below. The carrier concentrations (electrons or holes) in the graphene channel regions ntot can be approximated by

| (1) |

where n0 represents residual carrier concentration at Dirac point, which should be zero for an ideal, disorder-free graphene layer and none zero in present of charged impurities located either in the dielectric or at the graphene/dielectric interface [81]. represents the carrier concentration induced by the top-gate bias away from the Dirac point, . The expression for is obtained from the following equation relating VTG, Cox, and the quantum capacitance of the two-dimensional electrons in the graphene channel:

| (2) |

The total device resistance Rtot is given by

| (3) |

where Rchannel is the resistance of the graphene channel covered by top-gate electrode, the contact resistance Rcontact consists of the uncovered graphene section resistance and the metal/graphene contact resistance, and L and W represent the channel length and width the top-gated area [23]. By fitting this model to the measured data, the authors extracted a phenomenal mobility μ of 8600 cm2/Vs, representing the highest value achieved in top-gated transistors at the time of their report. This approach to use aluminum nucleation layer for ALD was also adopted to IBM scientists to fabricate top-gated graphene devices to achieve field effect mobility about 2700 cm2/Vs [24], a respectable value, although not as high as the first report (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

(a) Device schematic of the dual-gate graphene transistor. (b) SEM image of a double-channel graphene transistor. The channel width is 27 μm, and the gate length is 350 nm for each channel. (c) Measured channel conductance as a function of the back-gate voltage of a graphene device before and after the deposition of 12-nm-thick ALD Al2O3. Prior to the ALD process, a layer of 2-nm aluminum is deposited and oxidized as the nucleation layer. Adapted from [24].

The metal oxide as the buffer/nucleation layer has also been explored for the deposition of oxide on graphene using other approach such as molecular beam epitaxy (MBE). Wang et al. demonstrated that the growth of atomically smooth magnesium oxide (MgO) films on graphene surfaces by MBE [82]. By examining AFM images of MgO films with different growth rates on highly oriented pyrolytic graphite (HOPG) substrates, they find that the high surface diffusion leads to nonuniform MgO films with root mean square roughness > 0.8 nm. To reduce the mobility of surface atoms, they deposit Ti atoms to dress the graphene surface prior to the MgO deposition. Remarkably, with as little as a 0.5 ML (monolayer) coverage of Ti, the root mean square roughness of a 1 nm MgO film is dramatically reduced to be near the atomic spacing in MgO (0.211 nm). Because the metallic Ti islands on graphene may be undesirable for lateral transport, they oxidize the Ti prior to MgO growth and find that the MgO layer is atomically smooth under this condition as well. However, the mobility of these devices is still limited, as low as 800–1700 cm2/V·s.

The use of a thin metal (Al or Ti) film as a nucleation layer has enabled the ALD of continuous oxide dielectric (e.g. Al2O3) on graphene. The device results show mobility values of several thousand at room temperature, a finding which indicates that the top-gate stack does not severely increase the carrier scattering and consequently degrade the device characteristics.

3.4 Low-k polymer buffer layer for ALD dielectrics on graphene

Farmer et al. reported that the introduction of a low-k polymer buffer layer on graphene for ALD of high-κ dielectrics, and demonstrated top-gated devices without significant mobility degradation [14]. The low-k buffer layer consists of a commercially available polymer NFC 1400-3CP, which is a derivative of polyhydroxystyrene that is conventionally used as a planarizing underlayer in lithographic processes. It can be diluted in propylene glycol monomethyl ether acetate (PGMEA), and spin-coated onto the graphene surface. The dilution and spin speed can be adjusted to control the desired thickness and uniformity of the buffer layer. Methyl and hydroxyl groups contained within the polymer structure serve as functional groups for ALD of HfO2 using tetrakis(dimethylamido)-hafnium and water as precursor. In a typical process, approximately 10 nm thick polymer buffer layer was first spin coated and cured at 175 °C for 5 minutes to remove residual solvent, 10 nm thick HfO2 is deposited onto the buffer layer to complete the dielectric stack. The ALD was conducted at a relatively low temperature of 125 °C to produce HfO2 films with a dielectric constant of κ = 13. Capacitance analysis of the complete gate stack yields a dielectric constant of κ = 2.4 for the buffer layer.

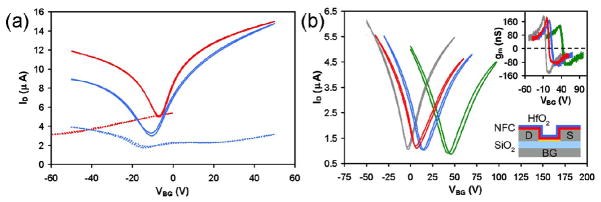

The impact the buffer dielectric processing on the transport properties of the back-gated graphene devices was examined by comparing two-point transfer characteristics (Fig. 10a) and transconductances (inset of Fig. 10a) at different stages of the processing. The two-point transconductance is defined as gm = dID/dVG, where ID is the drain current and VG is the gate voltage. The Dirac point voltage (VDirac) of the device before processing is VDirac = 3.5 V, in close proximity to 0 V, which signifies that the graphene is not significantly doped by the supporting 300 nm SiO2 substrate. The doping level became highly p-doped after application of the buffer layer (VDirac = 42.5 V), and then moderately p-doped after HfO2 ALD (VDirac = 13.25 V). After ALD, the device is subjected to an O2 plasma treatment which further shift the device toward neutral doping (VDirac = 5.75 V), but did not damage the graphene as indicated by relative little change in resistance or transconductance. This also demonstrates that the dielectric stack can effectively protect graphene from damaging by the plasma that is known to etch graphene. Beyond changing the doping level, buffered dielectric processing has a minimal effect on the transfer characteristics. Both the minimum current value at VDirac and the maximum hole transconductance remain within 15% of their initial values. There is a 40% decrease in the maximum electron transconductance, which is likely associated with doping-induced conductance asymmetry caused by the electrodes [83, 84]. The mobility values achieved here is 8500 cm2/Vs for back gated configuration (with top-gate dielectrics) and 7600 cm2/Vs for top-gate configuration. Overall, the results obtained using this buffer dielectric is a dramatic improvement compared to other methods of dielectric coating (Fig. 10b). Indeed, the authors have demonstrated in parallel experiments that devices made with the polymer buffer layer are significantly better than those made with the other approaches, such as NO2 functionalization and oxidized Al deposition discussed above.

Fig. 10.

Two-point back-gated measurements of graphene flakes. (a) Transfer characteristics and corresponding transconductances (inset) after the different stages of buffered dielectric processing: before processing (gray), after NFC polymer deposition (green), after HfO2 deposition (blue), and after 50 W O2 plasma treatments for 30 s (red). The schematic shows the completed device configuration. (b) Transfer characteristics of two devices before (solid lines) and after (dashed lines) alternative coating processes are employed. Two nanometers oxidized Al deposition (red) and NO2 functionalization (blue) is used instead of polymer coating. Both processes result in significant mobility degradation. VD = 10 mV for all measurements, and VBG is swept forward and backward to show current hysteresis. Adapted from [14].

The addition of a low-κ polymer buffer layer between graphene and conventional gate dielectrics helps minimize mobility degradation in top-gated graphene transistors. Possible reasons include the suppression of extrinsic surface phonons by the buffer layer and the reduction of the impurity concentration due to the inherent properties of the polymer. This new coating procedure represents a significant improvement over previous efforts, and will hopefully further the advancement of graphene transistors.

4. Physical assembly of high-κ oxide nanostructures as top-gate dielectrics for graphene transistors

Despite significant efforts devoted to the functionalization of graphene surface or introduction of buffer layer for ALD deposition of oxide dielectric on graphene, and significant advancements in this direction, these processes usually breaks the chemical bonds or introduces undesired impurities in the graphene lattice, inevitably leading to a significant degradation in device performance. Many of these processes can result in mobility degradation by nearly one order of magnitude. The use of aluminum buffer layer for high-κ deposition was demonstrated with improved device mobility, which, however, is still lower than that of normal back-gated graphene devices [4, 45, 49, 85, 86]. Introduction of a polymer buffer layer prior to high-κ deposition can mitigate the potential damage to graphene lattice, which however can limit the effective gate coupling due to the low-k polymer layer. To eventually realize high-performance graphene-based electronics, continued effort is necessary to develop alternative approaches that can enable graphene-dielectric integration without damaging the pristine graphene lattice. To this end, we have recently reported an entirely new strategy to integrate graphene with high-κ dielectrics by physical assembling free-standing oxide nanowires or nanoribbons on top of graphene [87–89]. Here we review the recent advancements in this regard.

Nanowire and nanoribbons can be synthesized at high temperature with nearly perfect crystalline structure, but manipulated and assembled at room temperature. This flexibility allows the integration of normally incompatible materials and processes and can enable unique new functions in electronics or photonics [53, 90–93]. Physical assembly of freestanding dielectric nanostructures on graphene represents the mildest approach for graphene-dielectric integration. Specifically, high quality dielectric nanostructures were first synthesized, and then transferred onto graphene as the gate dielectrics for top-gated graphene transistors. This integration approach preserves the pristine nature of the graphene and allows us to achieve the highest room temperature carrier mobility in top-gated graphene transistors to date. Fig. 11 illustrates our approach to fabricate top-gated graphene transistors using oxide nanostructures as the gate dielectrics. Oxide dielectric nanostructures (e.g. nanoribbons) were first aligned on top of the graphene through a physical dry transfer process, followed by lithography and metallization process to define the source and drain electrodes (Fig. 11a). Oxygen plasma etch was then used to remove the exposed graphene, leaving only the graphene protected underneath the dielectric nanostructure and the source drain electrodes (Fig. 11b). The top gate electrode was then fabricated to obtain a functional transistor (Fig. 11c).

Fig. 11.

Schematic illustration of the fabrication process to obtain top-gated graphene transistors using dielectric oxide nanostructures (e.g. nanoribbons) as the etching mask and top-gate dielectric. (a) A dielectric nanostructure is aligned on top of graphene using a dry-transfer process without any additional chemical functionalization to minimize the possibility to introduce defects/impurities into the graphene-dielectric interface, and the source-drain electrodes are fabricated by electron-beam lithography. (b) Oxygen plasma etch is used to remove the unprotected graphene, leaving only the graphene underneath the dielectric nanostructure connected to two large graphene blocks underneath the source and drain electrodes. (c) The top gate electrode is defined through lithography and metallization process. Adapted from [89]..

4.1 Dielectric properties of Al2O3 nanoribbons

Aluminum oxide (Al2O3) nanoribbons were used as an initial example to demonstrate the concept of using free-standing chemical nanostructures as the top gate dielectrics for graphene transistors [89], due to their excellent dielectric properties, thermal and chemical stability [94]. Al2O3 nanoribbons were synthesized through a physical vapour transport approach at 1200 °C [95]. Transmission electron microscope (TEM) studies show that the Al2O3 nanoribbons typically have a width of 1–3 microns, and a length on the order of 10 microns (Fig. 12a). Selected area electron diffraction (SAED) study shows the nanoribbon has a single crystalline α-Al2O3 structure, oriented along <110> direction in its long axis, and along <001> direction (c-plane) in its thickness (inset of Fig. 12a). The high resolution TEM image (HRTEM) confirms that the nanoribbon is a single crystal with nearly perfect crystalline structure free of any obvious defects (Fig. 12b). Atomic force microscopy (AFM) studies show the nanoribbons typically have a thickness around 15–150 nm (Fig. 12c), and nearly atomically smooth surface with root mean square roughness less than 0.2 nm (Fig 13d).

Fig. 12.

Evaluation of the Al2O3 nanoribbons as dielectric material. (a) TEM image (inset, SAED pattern) and (b) HRTEM image of an Al2O3 nanoribbon show nearly perfect crystalline structure with α-Al2O3 structure. (c) AFM image of an Al2O3 nanoribbon with thickness ~50 nm. The image area is 5 μm × 5 μm. (d) AFM image of the surface of the Al2O3 nanoribbon, highlighting the smooth surface with a root mean square roughness < 0.2 nm. The image area is 250 nm × 250 nm. (e) The schematic device diagram (inset) and SEM image of an Al2O3 nanoribbon metal-insulator-metal (MIM) device. (f) Current density-electric field (J-E) curve of an MIM device made from an Al2O3 nanoribbon, and the inset shows the corresponding Fowler–Nordheim (F-N) curve. Adapted from [89].

Fig. 13.

Characterization of the graphene/Al2O3 nanoribbon interface. (a) An optical image of an Al2O3 nanoribbon on graphene, the scale bar is 2 μm. (b) Raman spectra of the graphene with (b) and without (a) Al2O3 nanoribbon covering. There is no D-band in either spectrum, indicating that Al2O3 nanoribbon does not introduce any appreciable defects into graphene lattice. (c) A cross-section TEM image of the top gate stack, the scale bar is 100 nm. The inset shows an SEM image of a typical device, the scale bar indicates 5 μm. The dotted line in the inset shows the cross-section cutting direction. (d) A cross-section HRTEM image of the interface between Al2O3 nanoribbon and a tri-layer graphene. The partially incomplete graphene layers in the image are caused by electron beam damage during the TEM imaging process. Adapted from [89].

The intrinsic dielectric properties (current tunnelling, breakdown and dielectric constant) of the Al2O3 nanoribbons were characterized using a metal-insulator-metal (MIM) device (Fig. 12e). Current-voltage (I-V) measurements of the MIM device show typical Fowler–Nordheim (F-N) tunnelling behaviour with a breakdown field of ~8.5 MV/cm (Fig. 12f and inset), comparable to the best quality ALD Al2O3 film [94]. This type of field assisted tunnelling can be described by charge carrier tunnelling through a triangular barrier with:

| (4) |

where

| (5) |

and

| (6) |

J is current density, Eox is the oxide electric field, m* is the effective mass of the charge carrier, which is about 0.23me, and ΦB is the barrier height [94]. Fitting the I-V characteristics with F-N tunnelling model gives a tunnel barrier of about 2.0 eV between Al2O3 and Ti, comparable to previous reports of the barrier height between ALD Al2O3 and metals of similar work function [94, 96]. The relative dielectric constant is also determined as 8.5 from capacitance-voltage measurement, which is larger than typical values observed in ALD Al2O3 films. These studies clearly demonstrate that the Al2O3 nanoribbons have dielectric properties comparable to or better than the best quality ALD Al2O3 film, and can function as an excellent dielectric material for top-gated graphene transistors.

4.2 Dielectric nanostructure-graphene integration and interface

The Al2O3 nanoribbons can be aligned onto the top of the graphene through a solution assembly or physical transfer process. Previous studies have shown that the deposition of oxide on top of graphene often introduces significant defects into the graphene structure with an obvious defect band (D-band) emerging around 1350 cm−1 in Raman spectra [62]. To this end, micro-Raman spectroscopy was employed to investigate the interaction between an Al2O3 nanoribbon and the underlying graphene (Fig. 13a). Micro-Raman spectra were collected from bare graphene (point a) and Al2O3 nanoribbon covered graphene (point b). Significantly, there is no clear difference between two Raman spectra and there is no obvious D-band (Fig. 13b), in contrast to previous study in which an obvious D-band was observed [109]. Cross-sectional TEM was used to study the graphene-dielectric interface (Fig. 13c). The image of the device shows that the graphene layers are intimately integrated with the crystalline Al2O3 nanoribbon without any obvious gap or impurities between them (Fig. 13d). Together, these studies clearly demonstrate that the physical assembly approach can effectively integrate Al2O3 nanoribbon with graphene without introducing any appreciable defects into the graphene lattice, and thus can effectively preserve the high carrier mobility in the resulting devices.

4.3 Al2O3 nanoribbons as the top-gate dielectrics for graphene transistors

The electrical transport studies of the top-gated graphene transistors using Al2O3 nanoribbon gate dielectrics were carried out at room temperature. Fig. 14a shows the drain-source current (Ids) versus drain-source voltage (Vds) output characteristics of the transistor at various top-gate voltages (VTG). The device delivers an on-current of 675 μA at Vds = 1 V and Vg = −1.5 V. Importantly, the transfer characteristics (Ids versus top-gated voltage (VTG) and back-gated voltage (VBG)) shows the required gate voltage swing to achieve similar current modulation in top-gate configuration is more than one order of magnitude smaller than that in back-gate configuration (Fig. 14b dIds and inset). The transconductance can be extracted from the Ids-VTG curve dVTG (Fig. 14c). At Vds= 1 V, the top-gated device exhibits a max gm of about 290 μS, which is about 15 times larger than that of the back-gated configuration (gm ~ 19.5 μS).

Fig. 14.

Room temperature electrical properties of the top-gated graphene device using Al2O3 nanoribbon as the gate dielectric. (a) Ids-Vds output characteristics, the channel width and length of the device is 2.1μm and 4.1μm (b) Transfer characteristics at Vds = 1 V for the device using top and back gate (inset). (c) Transconductance gm as a function of top-gate voltage VTG, the inset shows the gm vs. VBG. The plots indicate the top-gate gm is about 15 times higher than the back-gate gm. Adapted from [89].

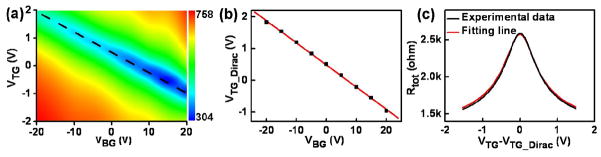

Fig. 15a further shows two-dimensional plot of the device conductance as a function of varying VBG and VTG bias, from which we can determine the top-gate Dirac point (VTG_Dirac) shift as a function of VBG (Fig. 15b). It gives the ratio between top-gate and back-gate capacitances, CTG/CBG ≈ 14.3. This gate capacitance ratio is consistent with the improvement factor (~15) in transconductance of top- versus back-gated configurations. Using the back-gate capacitance value of CBG = 11.5 nF/cm2, the top-gate capacitance is estimated to be CTG = 164.5 nF/cm2, corresponding to a relative dielectric constant of 8.4 for Al2O3 nanoribbon, which is also consistent with the value obtained from MIM devices.

Fig. 15.

Mobility determination in the top-gated graphene device using Al2O3 nanoribbon as the gate dielectric. (a) Two-dimensional plot of the device conductance at varying VBG and VTG bias. The unit in the color scale is μS. (b) The top-gate Dirac point VTG_Dirac at different VBG. (c) Experimental plot (black line) and modelling fitting (red line) of Rtot vs. VTG-VTG_Dirac relation to derive the contact resistance and carrier mobility. Adapted from [89].

We have used the same model described above [section 3.3] to fit the measured data and extract the relevant parameters, n0, Rcontact and μ. Fig. 15c shows the measured Rtot versus VTG (black line), along with the fitted curve derived from Eq. (3) (red line). The fitted curve agrees well with the experimental data, with a single value of the residual concentration n0 = 4.1 × 1011 cm−2, Rcontact = 1240 Ω, and the mobility = 22,400 cm2/V·s, which represents the highest carrier mobility value observed in top-gated graphene devices to date. Multiple devices were fabricated and tested with the same approach, all of which exhibited carrier mobilities well exceeding 10,000 cm2/V·s with highest mobility of reach 23,600 cm2/V·s, comparable to the best reported values in back-gated devices and significantly better than typical values previously reported for top-gated devices (Fig. 16). Together, these studies clearly demonstrate that the presence of Al2O3 nanoribbon on top of graphene does not lead to any mobility degradation, in contrast to previous efforts in using ALD or PVD to deposit dielectrics on graphene.

Fig. 16.

Table summarizing highest mobility values obtained in top-gated graphene transistors using various dielectric integration approaches.

4.4 ZrO2 nanowire as top-gate dielectric for graphene nanoribbon transistors

Taking a step further, ZrO2 nanwires with even higher dielectric constant (up to 23) [97, 98] were also explored as the gate dielectric for top-gated devices [88]. An additional attribute of using ZrO2 nanowires is that narrower graphene channels (e.g. graphene nanoribbons, GNR) can be readily fabricated to facilitate gap-opening and improve the transistor on-off ratio [30–33, 35, 99]. ZrO2 nanowires were synthesized through a chemical vapour deposition (CVD) process using ZrCl4 as the precursor. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) image shows that ZrO2 nanowires are about several tens of microns in length and 20–100 nm in diameter (Fig. 17a). TEM and SAED studies reveal that ZrO2 nanowires are amorphous (Fig. 17b and inset). The top-gated graphene transistors using ZrO2 nanowires as the gate dielectric can be fabricated using the same approach described above (Fig. 17c). Here the ZrO2 nanowire also functions as a nanoscale etch mask to define a narrow graphene nanoribbon with width in the 10–20 nm regime through aggressive over etch (inset, Fig. 17c) [35]. The Ids-Vds plots at various top-gate voltages (VTG) show clearly that the device conductance decreases as the gate potential increases towards positive direction (Fig. 17d), demonstrating that the graphene nanoribbon is p-type doped, which can be attributed to edge oxidation or the physisorbed O2 from ambient or during the device fabrication process. This device delivers an on-current of 28 μA at Vds = 1 V and Vg = −1.0 V. Transfer characteristics show a top-gated GNR transistor using ZrO2 nanowire dielectric can be switched on and off with only ~1 volt of gate swing (red curve in Fig. 17e), in contrast to 10–40 V required for back-gated devices (black curve in Fig. 17e). The device shows a room temperature on/off ratio of ~12 at Vds = 0.1 V, consistent with a graphene nanoribbon with estimated width of ~10–15 nm [30, 35]. The maximum transconductance gm at Vds = 1V is about 29 μS, more than 12 times larger than that of the back-gated configuration (~2.3 μS) (Fig. 17f).

Fig. 17.

ZrO2 NWs as the gate dielectric in top-gated GNR transistors. (a) An SEM image of ZrO2 nanowires. (b) A TEM image of a ZrO2 nanowire, and the inset shows the SAED pattern of a ZrO2 nanowire. (c) The SEM image of a top-gated GNR transistor with ZrO2 nanowire as top-gate dielectric. The gate length is about 500 nm and the diameter of the nanowire is 50 nm. Inset shows an AFM image of a ~15 nm wide GNR obtained under ZrO2 nanowire after oxygen plasma etching. The scale bar indicates 200 nm. (d) Ids-Vds output characteristics at variable top gate voltage starting from 0.4 V at bottom to −1.0 V at top in the step of −0.2 V. (e) Ids-VTG (red curve) and Ids-VBG (black curve) transfer characteristics at Vds = 1 V. (f) Transconductance gm as a function of top-gate voltage VTG and back gate voltage VBG (inset). Adapted from [88].

It is interesting to compare the top-gated graphene nanoribbon devices with state-of-the-art silicon MOSFETs. The effective on current Ion for an FET device is usually characterized at Vds= Vg(on-off) = Vdd, where Vg(on-off) is the gate voltage swing from off- to on-state and Vdd is the power supply voltage. Considering Vds = Vg(on-off) = Vdd = 1V, the Ion of our device at Vds =1V and 1 V gate swing from the off state is ~25μA. Taking the channel width of the graphene nanoribbons ~ 15 nm, we obtain the scaled values of Ion and gm of our device to be ~1.7 mA μm−1 and ~2.0 mS μm−1, already exceeding the values of 0.7 mA μm−1 and 0.8 mS μm−1 in sub-100-nm silicon p-MOSFETs and comparable to those of n-MOSFET devices employing high-κ dielectrics.[100]. This is significant considering the relatively large channel length (~ 1 μm) of the current device. It is reasonable to expect that the on-current and transconductance can be further improved to by shrinking the channel length. These studies demonstrate that ZrO2 nanowires can also function as effective gate dielectrics for high performance top-gated graphene nanoribbon devices.

4.5. Conductor/dielectric coreshell nanowires as the top-gate for graphene nanoribbon transistors

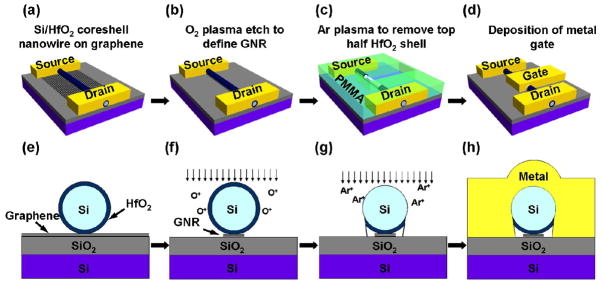

In the above discussions, pure dielectric nanostructures are explored as the top-gate dielectric for graphene transistors, in which the dielectric thickness is controlled by the overall dimension of the nanostructures and may be difficult to scale down to very small thickness (e.g. 1–2nm), due to the challenges to synthesize and assemble the oxide nanostructures at such small dimensions, and the potential difficulties to fabricate devices using such small structures. Alternatively, one can also explore conductor/dielectric coreshell nanostructures (nanowires or nanoribbons), in which the dielectrics are deposited on a conducting (e.g. metal or highly doped semiconductor) nanostructure using ALD, and can be precisely controlled down to 1 nm regime. Such coreshell nanowires can be used to fabricate top-gated graphene transistors using a similar approach described above, in which the oxide shell functions as the gate dielectrics with controlled thickness, and the conducting core functions as the self-integrated gate. Using such coreshell nanostructures, it is possible to fabricate top-gated graphene transistors with the dielectric thickness down to 1 nm or so (Fig. 18a-h). To establish the electrical contact between the silicon nanowire gate and the external gate electrode, an additional step of argon plasma treatment is needed to physically remove the HfO2 film on the top half of the nanowires prior to the deposition of the top gate electrode.

Fig. 18.

Schematic illustration of the fabrication process to obtain top-gated graphene transistors using Si/HfO2 coreshell nanowires as the etching mask and top-gate. (a) and (e), an Si/HfO2 coreshell nanowire is aligned on top of graphene using a dry-transfer process, and the source-drain electrodes are fabricated by electron-beam lithography (b) and (f), Oxygen plasma etch is used to remove the unprotected graphene, leaving only the GNR underneath the nanowire connected to two large graphene blocks underneath the source and drain electrodes. (c) and (g), The top-half of the HfO2 shell was etched away using argon plasma to expose the silicon core gate for contact to external electrode. (d) and (h), The top gate electrode is defined through lithography and metallization process. Adapted from [87].

Various type of conducting nanowires (highly doped silicon or metal silicide, NiSi, PtSi) can be explored for this purpose. For example, we have recently synthesized Si/HfO2 coreshell nanowires by ALD deposition of 2 nm thick HfO2 on highly-doped silicon nanowires (Fig. 19b and c) [87]. Such coreshell nanowires can be readily explored for top-gated graphene nanoribbon transistors. Here the HfO2 shell functions as the gate dielectrics with controlled thickness down to 1 nm, and the silicon core functions as the self-integrated gate. To contact the silicon core gate to external electrode, the top-half of the HfO2 shell was etched away using argon plasma. The cross section TEM image clearly shows the integrated silicon gate, 2-nm thick HfO2 gate dielectric, and the graphene nanoribbon (Fig. 20b and c).

Fig. 19.

TEM characterization of Si/HfO2 coreshell nanowires. (a) Schematic illustration of the synthesis of Si/HfO2 coreshell nanowires. Highly doped p-type silicon nanowire arrays were synthesized using catalytic chemical vapour deposition. Atomic layer deposition was used to grow HfO2 shell with controlled thickness. (b) TEM and (c) HRTEM images of Si/HfO2 coreshell nanowires. Adapted from [87].

Fig. 20.

Characterization of the graphene/HfO2 interface. (a) A SEM image of a typical device. (b) A cross-section TEM image of the top gate stack. (c) A cross-section HRTEM image of the interface between nanowires and a multi-layers graphene, which indicate that the graphene layers are intimately integrated with the Si/HfO2 nanowire without any obvious gap or impurities between them. A TEM image of multi-layer graphene device is shown here because it is very difficult to visualize the mono- or few-layer of graphene nanoribbon under the nanowire due to significant electron-beam damage while conducting TEM studies. Adapted from [87].

Electrical transport studies of the top-gated device were carried out in ambient conditions at room temperature. The gate tunnelling leakage current (Igs) from the Si/HfO2 core/shell nanowire to the underlying GNR is negligible within the gate voltage range of ± 1 V range (Fig. 21a). This measurement demonstrates that the 2 nm thick HfO2 dielectrics can function as an effective gate insulator for top-gated GNR transistors and afford high gate capacitance critical to the high transconductance. The drain-source current (Ids) vs. drain-source voltage (Vds) plots at various top-gate voltages (VTG) show clearly that the device conductance decreases as the gate potential increases towards positive direction (Fig. 21b), demonstrating that the GNR is p-type doped, which can be attributed to edge oxidation or the physisorbed O2 from ambient or during the device fabrication process. Fig. 21c shows the transfer characteristics drain-source current (Ids) versus top-gated voltage (VTG) curves for the same device at Vds = 0.1 and 1.0 V. The transfer characteristics show the device can be switched on and off with < 1 volt of gate swing, the smallest on-off gate swing ever achieved in GNR transistors. The device delivers an on-current of 27 μA at Vds = 1 V and Vg = −1.0 V, and shows a room temperature on/off ratio of ~ 70 at Vds = 0.1 V, consistent with a GNR with estimated width of ~10 nm.9–11 To evaluate the top-gated devices versus standard back-gated devices, we have measured the transfer characteristics, Ids-VTG and back-gated voltage (VBG). Significantly, the required gate voltage swing to achieve a similar current modulation in top-gate configuration is more than one order of magnitude smaller than that in back-gate configuration (Fig. 21d). The transconductance can be extracted from the Ids-VTG curve. The maximum gm in the top-gated device at Vds = 1V is about 32 μS (Fig. 21e), nearly 20 times larger than the value obtained in the back-gated configuration (~1.7 μS) (inset, Fig. 21e).

Fig. 21.

Room temperature electrical properties of the top-gated GNR device by using Si/HfO2 coreshell as the top-gate. (a) Gate leakage current versus top-gate voltage. The leakage current is negligible (at the nA level) within ± 1 V range. (b) Ids-Vds output characteristics at variable top-gate voltage starting from 0.6 V at bottom to -1.0 V at top in the step of -0.2 V. (c) The transfer characteristics Ids-VTG at Vds = 0.10 and 1.0 V. (d) Ids-VTG and Ids-VBG transfer characteristics at Vds = 1 V. (e) Transconductance as a function of top-gate voltage VTG and back gate voltage VBG (inset). (f) Two-dimensional plot of the device conductance at varying VBG and VTG bias, the unit in the color scale is μS. Adapted from [87].

4.6. Integrated device array from nanowire gated graphene nanoribbon transistors

The ability to fabricate the top-gated graphene nanoribbon devices readily allows integration of multiple GNR FETs into functional device arrays. (Fig. 22a and b), and therefore allowing for diverse electronic functions. For example, a logic OR gate is obtained with two independent gate electrodes fabricated on a GNR in conjunction with a loading resistor (Fig. 22c). The OR function occurs because the output voltage is low only when input to both gates is at low voltages (Fig. 22d). When one or both gates are at high voltages, the GNR channel is electrically shut off, resulting in a high output voltage.

Fig. 22.

Independently addressable GNR device array. (a) An SEM image of two independently addressable top-gated GNR FETs. (b) Transfer characteristics of two top-gated GNR FETs at Vds = 0.1 V. (c) The SEM image of a logic OR gates built from GNR transistors. The inset shows the schematic circuit diagram. (d) The OR gate output characteristics with double top-gates. The operating voltage is Vdd = 1V. The inputs for the two gates, A and B, are 1V for state 1 and 0 for state 0. Adapted from [88].

5. Summary

Graphene is emerging as an interesting electronic material for future electronics due to their exceptionally high carrier mobility, tunable band gap and atomically thin structure. The gate dielectric is an essential component of a transistor and can significant impact the critical device parameters including transconductance, subthreshold swing and frequency response. Exploring graphene for future electronics requires its effective integration with high quality gate dielectrics, in particular the high-k dielectrics, which is of significant challenge due to the intrinsic incompatibility between pristine graphene and oxide dielectrics. Physical vapour deposition (PVD) such as electron-beam evaporation or sputtering process has been used to deposit dielectrics, although the PVD process usually yields lower quality dielectrics and can cause significant damages to graphene. The deposition of high-k dielectrics using ALD requires reactive surface groups. Functionalization of graphene surface for ALD either introduces undesired impurities or breaks the chemical bonds in the graphene lattice, inevitably leading to a significant degradation in carrier mobilities. As a result, the mobility values observed in the top-gated devices are typically nearly one order of magnitude smaller than what can be achieved in the back-gated devices. Recently, the introducing of polymer or aluminum buffer layer for high-k deposition was demonstrated with improved the device mobility, which, however, is still lower than best values observed in back-gated graphene devices. A newly developed physical assembly approach to integrate graphene with free-standing dielectric nanostructures can minimize potential damage to graphene lattice, and have enabled the highest mobility top-gated graphene transistors ever. This method opens a new avenue to integrate high-k dielectrics on graphene with the preservation of high carrier mobility. With further optimization of dielectric nanostructure growth and assembly process to precisely control their physical dimension and spatial location, large arrays of top-gated graphene transistors or circuits can be envisioned. This physical assembly and integration approach can thus open a new avenue to high performance graphene electronics, which can impact significantly high speed high frequency circuits and enable an entirely new generation of flexible, wearable or disposable electronics for computing, storage and wireless communication.

Fig. 5.

ALD of Al2O3 on pristine graphene. (a) AFM image of graphene on SiO2 before ALD. The height of the triangular shaped graphene is ~1.7 nm as shown in the height profile along the dashed line cut. Scale bar is 200 nm. (b) AFM image of the same area as (a) after ~2 nm Al2O3 ALD deposition. The height of the triangular shaped graphene becomes ~−0.3 nm as shown in the height profile along the dashed line cut. Scale bar is 200 nm. (c) and (d) Schematics of graphene on SiO2 before and after ALD. The Al2O3 grows preferentially on graphene edge and defect sites. Adapted from [73].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Graphene, in.

- 2.Dato A, Lee Z, Jeon KJ, Erni R, Radmilovic V, Richardson TJ, Frenklach M. Chemical Communications. 2009:6095–6097. doi: 10.1039/b911395a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geim AK, Novoselov KS. Nature Materials. 2007;6:183–191. doi: 10.1038/nmat1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Novoselov KS, Geim AK, Morozov SV, Jiang D, Zhang Y, Dubonos SV, Grigorieva IV, Firsov AA. Science. 2004;306:666–669. doi: 10.1126/science.1102896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bunch JS, Yaish Y, Brink M, Bolotin K, McEuen PL. Nano Letters. 2005;5:287–290. doi: 10.1021/nl048111+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Novoselov KS, Geim AK, Morozov SV, Jiang D, Katsnelson MI, Grigorieva IV, Dubonos SV, Firsov AA. Nature. 2005;438:197–200. doi: 10.1038/nature04233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang YB, Tan YW, Stormer HL, Kim P. Nature. 2005;438:201–204. doi: 10.1038/nature04235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berger C, Song ZM, Li XB, Wu XS, Brown N, Naud C, Mayou D, Li TB, Hass J, Marchenkov AN, Conrad EH, First PN, de Heer WA. Science. 2006;312:1191–1196. doi: 10.1126/science.1125925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avouris P, Chen ZH, Perebeinos V. Nature Nanotechnology. 2007;2:605–615. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen ZH, Lin YM, Rooks MJ, Avouris P. Physica E. 2007;40:228–232. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolotin KI, Sikes KJ, Jiang Z, Klima M, Fudenberg G, Hone J, Kim P, Stormer HL. Solid State Communications. 2008;146:351–355. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Du X, Skachko I, Barker A, Andrei EY. Nature Nanotechnology. 2008;3:491–495. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miao F, Wijeratne S, Zhang Y, Coskun UC, Bao W, Lau CN. Science. 2007;317:1530–1533. doi: 10.1126/science.1144359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farmer DB, Chiu HY, Lin YM, Jenkins KA, Xia FN, Avouris P. Nano Letters. 2009;9:4474–4478. doi: 10.1021/nl902788u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moon JS, Curtis D, Hu M, Wong D, McGuire C, Campbell PM, Jernigan G, Tedesco JL, Vanmil B, Myers-Ward R, Eddy C, Gaskill DK. IEEE Electron Device Letters. 2009;30:3. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geim AK. Science. 2009;324:1530–1534. doi: 10.1126/science.1158877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorbachev RV, Mayorov AS, Savchenko AK, Horsell DW, Guinea F. Nano Letters. 2008;8:1995–1999. doi: 10.1021/nl801059v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mak KF, Lui CH, Shan J, Heinz TF. Physical Review Letters. 2009;102:256405. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.256405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang F, Zhang YB, Tian CS, Girit C, Zettl A, Crommie M, Shen YR. Science. 2008;320:206–209. doi: 10.1126/science.1152793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang YB, Tang TT, Girit C, Hao Z, Martin MC, Zettl A, Crommie MF, Shen YR, Wang F. Nature. 2009;459:820–823. doi: 10.1038/nature08105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrari AC, Meyer JC, Scardaci V, Casiraghi C, Lazzeri M, Mauri F, Piscanec S, Jiang D, Novoselov KS, Roth S, Geim AK. Physical Review Letters. 2006;97:187401. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.187401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murali R, Yang YX, Brenner K, Beck T, Meindl JD. Applied Physics Letters. 2009;94:243114. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meric I, Han MY, Young AF, Ozyilmaz B, Kim P, Shepard KL. Nature Nanotechnology. 2008;3:654–659. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin YM, Chiu HY, Jenkins KA, Farmer DB, Avouris P, Valdes-Garcia A. IEEE Electron Device Letters. 2010;31:68–70. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin YM, Dimitrakopoulos C, Jenkins KA, Farmer DB, Chiu HY, Grill A, Avouris P. Science. 2010;327:662–662. doi: 10.1126/science.1184289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeon DY, Lee KJ, Kim M, Kim DC, Chung HJ, Woo YS, Seo S. Japanese Journal of Applied Physics. 2009;48:091601. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin YM, Jenkins KA, Valdes-Garcia A, Small JP, Farmer DB, Avouris P. Nano Letters. 2009;9:422–426. doi: 10.1021/nl803316h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xia FN, Mueller T, Lin YM, Valdes-Garcia A, Avouris P. Nature Nanotechnology. 2009;4:839–843. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Son YW, Cohen ML, Louie SG. Physical Review Letters. 2006;97:216903. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.216803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han MY, Ozyilmaz B, Zhang YB, Kim P. Physical Review Letters. 2007;98:206805. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.206805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li XL, Wang XR, Zhang L, Lee SW, Dai HJ. Science. 2008;319:1229–1232. doi: 10.1126/science.1150878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang XR, Ouyang YJ, Li XL, Wang HL, Guo J, Dai HJ. Physical Review Letters. 2008;100:206803. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.206803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiao LY, Zhang L, Wang XR, Diankov G, Dai HJ. Nature. 2009;458:877–880. doi: 10.1038/nature07919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bai JW, Zhong X, Jiang S, Huang Y, Duan XF. Nature Nanotechnology. 2010;5:190–194. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bai JW, Duan XF, Huang Y. Nano Letters. 2009;9:2083–2087. doi: 10.1021/nl900531n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silvestrov PG, Efetov KB. Physical Review Letters. 2007;98:016802. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.016802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ponomarenko LA, Schedin F, Katsnelson MI, Yang R, Hill EW, Novoselov KS, Geim AK. Science. 2008;320:356–358. doi: 10.1126/science.1154663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abergel DSL, Russell A, Fal’ko VI. Applied Physics Letters. 2007;91:063125. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blake P, Hill EW, Neto AHC, Novoselov KS, Jiang D, Yang R, Booth TJ, Geim AK. Applied Physics Letters. 2007;91:063124. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ni ZH, Wang HM, Kasim J, Fan HM, Yu T, Wu YH, Feng YP, Shen ZX. Nano Letters. 2007;7:2758–2763. doi: 10.1021/nl071254m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roddaro S, Pingue P, Piazza V, Pellegrini V, Beltram F. Nano Letters. 2007;7:2707–2710. doi: 10.1021/nl071158l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao LB, Ren WC, Li F, Cheng HM. ACS Nano. 2008;2:1625–1633. doi: 10.1021/nn800307s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liao L, Bai JW, Qu YQ, Huang Y, Duan XF. Nanotechnology. 2010;21:015705. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/21/1/015705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hong X, Posadas A, Zou K, Ahn CH, Zhu J. Physical Review Letters. 2009;102:136808. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.136808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen JH, Jang C, Xiao SD, Ishigami M, Fuhrer MS. Nature Nanotechnology. 2008;3:206–209. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen F, Xia JL, Ferry DK, Tao NJ. Nano Letters. 2009;9:2571–2574. doi: 10.1021/nl900725u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen F, Xia JL, Tao NJ. Nano Letters. 2009;9:1621–1625. doi: 10.1021/nl803922m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shishir RS, Ferry DK. Journal of Physics-Condensed Matter. 2009;21:232204. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/21/23/232204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tan YW, Zhang Y, Bolotin K, Zhao Y, Adam S, Hwang EH, Das Sarma S, Stormer HL, Kim P. Physical Review Letters. 2007;99:246803. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.246803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bolotin KI, Sikes KJ, Hone J, Stormer HL, Kim P. Physical Review Letters. 2008;101:096802. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.096802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ponomarenko LA, Yang R, Mohiuddin TM, Katsnelson MI, Novoselov KS, Morozov SV, Zhukov AA, Schedin F, Hill EW, Geim AK. Physical Review Letters. 2009;102:206603. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.206603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peter F, Szot K, Waser R, Reichenberg B, Tiedke S, Szade J. Applied Physics Letters. 2004;85:2896–2898. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang Y, Duan XF, Cui Y, Lauhon LJ, Kim KH, Lieber CM. Science. 2001;294:1313–1317. doi: 10.1126/science.1066192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Javey A, Kim H, Brink M, Wang Q, Ural A, Guo J, McIntyre P, McEuen P, Lundstrom M, Dai HJ. Nature Materials. 2002;1:241–246. doi: 10.1038/nmat769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wind SJ, Appenzeller J, Martel R, Derycke V, Avouris P. Applied Physics Letters. 2002;80:3817–3819. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berger C, Song ZM, Li TB, Li XB, Ogbazghi AY, Feng R, Dai ZT, Marchenkov AN, Conrad EH, First PN, de Heer WA. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2004;108:19912–19916. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gu G, Nie S, Feenstra RM, Devaty RP, Choyke WJ, Chan WK, Kane MG. Applied Physics Letters. 2007;90:253507. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lemme MC, Echtermeyer TJ, Baus M, Kurz H. IEEE Electron Device Letters. 2007;28:282–284. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Das A, Pisana S, Chakraborty B, Piscanec S, Saha SK, Waghmare UV, Novoselov KS, Krishnamurthy HR, Geim AK, Ferrari AC, Sood AK. Nature Nanotechnology. 2008;3:210–215. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kedzierski J, Hsu PL, Healey P, Wyatt PW, Keast CL, Sprinkle M, Berger C, de Heer WA. IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices. 2008;55:2078–2085. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu YQ, Ye PD, Capano MA, Xuan Y, Sui Y, Qi M, Cooper JA, Shen T, Pandey D, Prakash G, Reifenberger R. Applied Physics Letters. 2008;92:092102. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ni ZH, Wang HM, Ma Y, Kasim J, Wu YH, Shen ZX. ACS Nano. 2008;2:1033–1039. doi: 10.1021/nn800031m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Robertson J. Reports on Progress in Physics. 2006;69:327–396. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee BK, Park SY, Kim HC, Cho K, Vogel EM, Kim MJ, Wallace RM, Kim JY. Applied Physics Letters. 2008;92:203102. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang FH, Yang RT. Carbon. 2002;40:437–444. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xuan Y, Wu YQ, Shen T, Qi M, Capano MA, Cooper JA, Ye PD. Applied Physics Letters. 2008;92:013101. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Farmer DB, Gordon RG. Nano Letters. 2006;6:699–703. doi: 10.1021/nl052453d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Leskela M, Ritala M. Thin Solid Films. 2002;409:138–146. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hashimoto A, Suenaga K, Gloter A, Urita K, Iijima S. Nature. 2004;430:870–873. doi: 10.1038/nature02817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Williams JR, DiCarlo L, Marcus CM. Science. 2007;317:638–641. doi: 10.1126/science.1144657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lin YM, Perebeinos V, Chen ZH, Avouris P. Physical Review B. 2008;78:161409. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lemme MC, Echtermeyer TJ, Baus M, Szafranek BN, Bolten J, Schmidt M, Wahlbrink T, Kurz H. Solid-State Electronics. 2008;52:514–518. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang XR, Tabakman SM, Dai HJ. Journal of The American Chemical Society. 2008;130:8152–8153. doi: 10.1021/ja8023059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Groner MD, Fabreguette FH, Elam JW, George SM. Chemistry of Materials. 2004;16:639–645. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hoshino A, Isoda S, Kurata H, Kobayashi T. Journal of Applied Physics. 1994;76:4113–4120. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ostrick JR, Dodabalapur A, Torsi L, Lovinger AJ, Kwock EW, Miller TM, Galvin M, Berggren M, Katz HE. Journal of Applied Physics. 1997;81:6804–6808. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kim S, Nah J, Jo I, Shahrjerdi D, Colombo L, Yao Z, Tutuc E, Banerjee SK. Applied Physics Letters. 2009;94:062107. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dignam MJ, Fawcett WR, Bohni H. Journal of The Electrochemical Society. 1966;113:656–657. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chang CC, Fraser DB, Grieco MJ, Sheng TT, Haszko SE, Kerwin RE, Marcus RB, Sinha AK. Journal of The Electrochemical Society. 1978;125:787–792. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ishigami M, Chen JH, Cullen WG, Fuhrer MS, Williams ED. Nano Letters. 2007;7:1643–1648. doi: 10.1021/nl070613a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Adam S, Hwang EH, Galitski VM, Das Sarma S. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:18392–18397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704772104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang WH, Han W, Pi K, McCreary KM, Miao F, Bao W, Lau CN, Kawakami RK. Applied Physics Letters. 2008;93:183107. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Farmer DB, Golizadeh-Mojarad R, Perebeinos V, Lin YM, Tulevski GS, Tsang JC, Avouris P. Nano Letters. 2009;9:388–392. doi: 10.1021/nl803214a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Huard B, Stander N, Sulpizio JA, Goldhaber-Gordon D. Physical Review B. 2008;78:121402. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Morozov SV, Novoselov KS, Katsnelson MI, Schedin F, Elias DC, Jaszczak JA, Geim AK. Physical Review Letters. 2008;100:016602. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.016602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Barreiro A, Lazzeri M, Moser J, Mauri F, Bachtold A. Physical Review Letters. 2009;103:076601. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.076601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Liao L, Bai JW, Cheng R, Lin YC, Jiang S, Huang Y, Duan XF. Nano Letters. 2010;10:1917–1921. doi: 10.1021/nl100840z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Liao L, Bai JW, Lin YC, Qu YQ, Huang Y, Duan XF. Advanced Materials. 2010;22:1941–1945. doi: 10.1002/adma.200904415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liao L, Bai JW, Qu YQ, Lin YC, Li YJ, Huang Y, Duan XF. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:6711–6715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914117107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Whang D, Jin S, Wu Y, Lieber CM. Nano Letters. 2003;3:1255–1259. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tao A, Kim F, Hess C, Goldberger J, He RR, Sun YG, Xia YN, Yang PD. Nano Letters. 2003;3:1229–1233. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Duan XF, Niu CM, Sahi V, Chen J, Parce JW, Empedocles S, Goldman JL. Nature. 2003;425:274–278. doi: 10.1038/nature01996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rogers JA, Nuzzo RG. Materials Today. 2005;8:50–56. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Groner MD, Elam JW, Fabreguette FH, George SM. Thin Solid Films. 2002;413:186–197. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fang XS, Ye CH, Peng XS, Wang YH, Wu YC, Zhang LD. Journal of Materials Chemistry. 2003;13:3040–3043. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Afanas’ev VV, Houssa M, Stesmans A, Adriaenssens GJ, Heyns MM. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids. 2002;303:69–77. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Perkins CM, Triplett BB, McIntyre PC, Saraswat KC, Shero E. Applied Physics Letters. 2002;81:1417–1419. [Google Scholar]