Abstract

Plasma cell neoplasms result from the clonal expansion of terminally differentiated, immunoglobulin heavy-chain class switched B-cells that typically secrete a monoclonal immunoglobulin. The 2008 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of plasma cell neoplasms encompasses a broad spectrum of disorders, from the precursor disorder monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) to plasma cell leukemia. The classification includes, in addition to precursor lesion MGUS, plasma cell myeloma, plasmacytoma, immunoglobulin deposition diseases and osteosclerotic myeloma.

Plasma cell myeloma is further divided into symptomatic plasma cell myeloma or multiple myeloma (MM), asymptomatic smoldering myeloma (SMM), non-secretory myeloma, and plasma cell leukemia. Although histopathological cut-off criteria are incorporated into the classification schema, distinction between MGUS, SMM, and MM depends primarily on the presence or absence of end-organ damage, as defined by “CRAB” criteria (hypercalcemia, renal insufficiency, anemia, lytic bone lesions, or a combination of these). Systematic evaluation of pathogenetic differences between MGUS and MM should offer invaluable insights into early myelomagenesis. Given the complex, intertwined nature of the malignant plasma cell and its surroundings, multiple pathogenetic mechanisms play a critical role in interactions between neoplastic cells and their microenvironment. Understanding the events leading to end-organ damage, like anemia and bone remodeling, is a critical part of investigating early myelomagenesis and should provide us with better tools for early identification and treatment of these patients.

Background

According to the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER), multiple myeloma (MM) is estimated to afflict nearly 20,000 individuals in the year 2010 and cause an estimated 10,000 deaths annually [1]. A quintessential example of how tumor exploits local niche, MM relies heavily on the bone marrow microenvironment for cues on tumor proliferation, survival mechanisms, drug resistance, and bone remodeling. Recent studies confirm previous suspicions that MM is preceded by a benign precursor disease, monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance (MGUS) [2]. Furthermore, most MM clonal genetic aberrations arise during precursor MGUS stages [3]. However, it is also known that patients with MGUS are at a low risk of progression to MM, having on average 1% annual risk [4]. Capturing and characterizing early myelomagenesis and identifying patients at high risk of progression presents a unique challenge that needs further attention. The first step in investigation of early disease requires clearldefinition of the spectrum of monoclonal gammopathies and determining where “early disease” fits into the spectrum. Better identification of patients with early disease at high risk of progression is warranted.

Histopathological studies of patients with precursor disease are scarce and there is very little data about key pathogenetic events associated with MGUS transition into MM in patients that do progress. Improved techniques need to be developed in order to detect meaningful bone marrow changes at earlier stages. By addressing such early events, future research emphasis can be placed on developing sensitive diagnostic techniques and advancing preventive therapeutics, perhaps impacting complications and natural progression of end stage resistant MM.

Spectrum of Plasma Cell Neoplasms and Diagnostic Criteria

Plasma cell neoplasms arise from a terminally differentiated, immunoglobulin heavy-chain class of switched clonal B cells that usually secrete monoclonal immunoglobulin or paraprotein. The 2008 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of plasma cell neoplasms has classified the broad spectrum of disorders into MGUS, plasma cell myeloma, plasmacytoma, immunoglobulin deposition diseases, and osteosclerotic myeloma or POEMS syndrome (table 1). Plasma cell myeloma is further divided into symptomatic plasma cell myeloma or multiple myeloma (MM), asymptomatic plasma cell myeloma or smoldering myeloma (SMM), non-secretory myeloma, and plasma cell leukemia. Diagnostic criteria that distinguish MGUS and SMM from MM include the lack of end organ damage, as defined by CRAB criteria: hypercalcemia, renal insufficiency, anemia, lytic bone lesions, or a combination of these (table 2) [5].

Table 1.

WHO Classification of Plasma Cell Neoplasms [5]

| Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance (MGUS) |

|---|

| Plasma Cell Myeloma |

| Asymptomatic Smoldering Myeloma |

| Symptomatic Multiple Myeloma |

| Non-secretory Myeloma |

| Plasma cell leukemia |

| Plasmacytoma |

| Solitary plasmacytoma of bone |

| Extraosseous (extramedullary) plasmacytoma |

| Immunoglobulin deposition diseases |

| Primary amyloidosis |

| Systemic light and heavy chain deposition disease |

| Osteosclerotic myeloma (POEMS syndrome) |

Table 2.

International Myeloma Working Group Diagnostic Criteria [6]

| MGUS | M protein < 3.0 g/dL AND Clonal bone marrow plasma cells < 10% AND No evidence of end-organ damage (CRAB) |

| Smoldering Myeloma | M protein > 3.0 g/dL AND/OR Clonal bone marrow plasma cells > 10% AND No evidence of end-organ damage (CRAB) |

| Multiple Myeloma | M protein in serum or urine* AND Clonal bone marrow plasma cells or plasmacytoma AND Evidence of end-organ damage (CRAB) Hypercalcemia (Calcium > 11.5 g/dL) Renal Insufficiency (Creatinine > 2.0 mg/dL) Anemia (Hemoglobin < 10 g/dL or 2 g/dL below baseline) Bone disease (bone lytic lesions or osteoporosis) |

Monoclonal protein may be absent in non-secretory multiple myeloma

Not considered a neoplasm but rather a precursor disease, MGUS is defined by monoclonal protein <3.0 g/dL, bone marrow clonal plasma cells <10% on trephine biopsy, and lack of end organ damage (figure 1) [6]. Prevalence of monoclonal isotypes in MGUS are 70% IgG, 15% IgM, 12% IgA, and 3% biclonal. The prevalence of IgD or IgE MGUS isotypes is very low [7]. Risk of progression from MGUS to MM or a related lymphoproliferative malignancy (lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, or Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia) approximates 1% per year, and does not occur in every patient [4]. Indeed, further risk stratification suggests MGUS patients with non-IgG isotype, monoclonal protein ≥ 1.5 g/dL, and abnormal free light chain ratios have higher risk of progression [8].

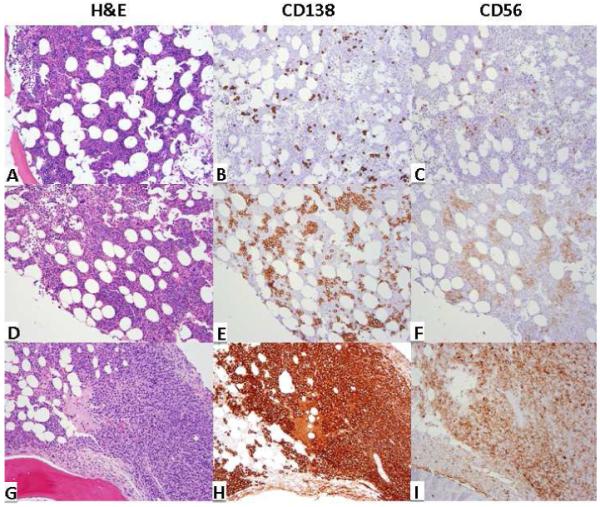

Figure 1. Bone marrow histopathological changes in patients with MGUS, SMM and MM.

Representative microphotographs of patients with MGUS (A, B, C), smoldering myeloma (D,E, F) and active myeloma (G, H, I). Plasma cell percent involvement is estimated based on CD138 immunohistochemial staining of bone marrow core biopsies. Clonal plasma cells aberrantly express CD56 in all three cases (Magnification 100x).

MGUS marrow aspirates contain a median of 3% plasma cells. Immunohistochemical staining of trephine biopsies facilitates enumeration of plasma cells and usually demonstrates interstitially scattered CD138 positive plasma cells, occasionally found in small clusters [7]. Detection of plasma cells that express monotypic cytoplasmic Ig of the same isotype as M-protein is often difficult due to small clone in the background of normal plasma cells. Plasma cells found in MGUS are typically mature cells with few atypical characteristics, such as presence of nucleoli and cytoplasmic inclusions.

SMM is defined by either monoclonal protein ≥ 3.0 g/dL or bone marrow clonal plasma cells ≥10% with absence of end organ damage(figure 1) [6]. Based on retrospective data from the Mayo Clinic, risk of progression to MM is 10% per year for the first 5 years, 3% per year for the next 5 years, and 1% for subsequent 10 years [9]. SMM risk models suggest that size of monoclonal protein (>3 g/dL) and percent of clonal plasma cells (>10%) in bone marrow along with presence of abnormal FLC ratio carries prognostic information on predicting those patients that develop MM [9]. However, diagnosis of early plasma cell myeloma currently represents a histopathological challenge since it depends on estimation of ≥10% percent of clonal plasma cells in bone marrow samples. Bone marrow sample size, type and quality of staining used, and observation bias are all factors that contribute to this challenge.

Symptomatic plasma cell myeloma or multiple myeloma (MM) requires presence of monoclonal protein in serum or urine and/or clonal plasma cells in bone marrow, or plasmacytoma with presence of end organ damage. Laboratory cut-off values for monoclonal protein or percentage of clonal plasma cells in bone marrow are not required for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma, but most cases demonstrate monoclonal protein ≥3.0 g/dL and bone marrow clonal plasma cells >10% (figure 1). 20% of MM patients secrete light chains, and 3% are non-secretory [6]. Serum free light chains and free light chain ratio aid in tracking disease burden among light chain secretors. Isotype prevalence among MM includes 50% IgG, 20% IgA, and ≤ 10% comprise IgE, IgD, IgM, and biclonal subtypes [6]. Bone marrow biopsy features commonly associated with MM include large clusters, nodules or diffuse sheets of plasma cells. There is typically progression from interstitial and focal disease in early myeloma to diffuse involvement in advanced disease with decrease in hematopoiesis, increase in osteoclasts, increase in cellularity, and an increase in marrow fibrosis [10]. In bone marrow aspirates, myeloma plasma cells vary from normal plasma cells to immature, plasmablastic and pleomorphic forms. In 15% of cases, plasma cells can be found on peripheral blood smears [5]. Abundant plasmacytosis (>20% of leukocyte differential or over 2×109/L) denotes plasma cell leukemia [6].

Recently, flow cytometric studies showed that aberrant expression of three cell surface markers (CD 45−, CD56+, and CD 19−) can distinguish clonal plasma cells in monoclonal gammopathies (MGUS, SMM, and MM) from normal plasma cells in more that 80% of cases (figure 1) [11]. Along with other risk factors, such as DNA aneuploidy, presence of >95% aberrant plasma cells in bone marrow samples was associated with higher progression to MM from SMM or MGUS [11]. Whether participating in cell adhesion, immune evasion or some other cellular function, the exact role these cell surface molecules play in pathogenesis of disease remains largely unknown. Up to 67-79% of MM cases demonstrate aberrant expression of CD56 [12]. Aggressive plasma cell leukemia is often accompanied by loss of CD56 expression, perhaps heralding a decrease in marrow tethering effect [13].

Effects on Hematopoiesis

Per diagnostic criteria, progression from MGUS/SMM to MM is marked by the presence of end organ damage, including anemia. In fact, hematopoietic hypoplasia is a frequent feature demonstrated on MM bone marrow biopsies that is largely attributed to replacement of marrow elements by tumor burden. Despite this, red blood cells seem to be the most affected hematopoietic lineage given the predominance of anemia and lack of other cytopenias in many patients. One theory suggests that erythroid progenitors from MM patients may undergo upregulation of FAS+ molecules, thus exposing them to increased apoptosis and destruction not seen in MGUS [14]. Others speculate that anemia is largely driven by reduced erythropoietin levels as a result of renal insufficiency, ignoring the observation that non-renal insufficient MM patients also develop anemia. More recent studies suggest that anemia accompanied by MM may be a function of iron dysregulation. Urine and serum hepcidin levels have been noted to be elevated in newly diagnosed MM patients compared to normal healthy controls. Such increased hepcidin levels may be linked to cytokine effects of IL-6 and bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2) found to dominate the myeloma bone marrow microenvironment [15]. Future studies are needed to define underlying mechanisms of hematopoietic hypoplasia in patients with MM.

Bone Remodeling

The rich interplay between myeloma tumor cells and microenvironment creates a unique niche where bone destruction thrives in the clinical form of pathologic fractures, bone pain, and severe osteoporosis. Bone remodeling becomes uncoupled in favor of increased osteoclast activity while osteoblast-driven bone formation is suppressed. Although frank osteolytic bone lesions are not present in MGUS, these patients have increased risk of fractures compared to healthy controls, suggesting early clinical signs of bone remodeling [16].

Indeed, MGUS patients have evidence of bone resorption and increased osteoclast activity as demonstrated by early bone histomorphometric studies [17]. Found to be upregulated in MM, the receptor of NF-k B ligand (RANK-L) and macrophage inflammatory protein-1a (MIP-1a) are key inducers of osteoclasts. Osteoprotegerin (OPG) is a potent inhibitor of osteoclast differentiation and is shown to be downregulated in myeloma derived osteoblasts and stromal cells. Serum bone resorption markers may help distinguish bone remodeling pathways involved in early and late myelomagenesis. For instance, compared to healthy controls, soluble RANK-L and RANK-L/OPG ratio in serum of MGUS patients is increased; even higher RANK-L and ratio is found in MM patients. Additionally, MM patients demonstrate increased MIP-1a not found to be elevated in MGUS patients or healthy controls [18]. The RANK-L/RANK/OPG pathway may be an early and sustained contributor of bone remodeling, whereas MIP-1a may be a late regulator independent or dependent of RANK-L.

Some studies suggest that as osteoclast activity increases in later disease states, significant bone disease is largely attributed to suppression of new bone formation, accelerating the pathogenesis of MM. In a study comparing bone formation rates using dynamic histomorphometric techniques, osteoblast recruitment was significantly increased in early myeloma compared to both MGUS and late symptomatic myeloma patients [19]. This might be due to changes in regulation of a critical pathway in normal bone physiology, the Wnt pathway, which potentiates osteoblast progenitor differentiation. Serum concentrations of Dikkopf1 (DKK1), a Wnt signaling antagonist, increase in Stage II/III MM patients compared to Stage I and MGUS patients [20]. Early myeloma microenvironment thus may provide an intact environment for osteoblasts to differentiate and function, perhaps even overcompensating for bone osteolysis.

Improvement of diagnostic techniques may allow for future characterization of pathologic bone remodeling in earlier disease states, such as MGUS and SMM. Since our current definition of MM relies heavily on recognizing presence of end organ damage, sensitive studies designed to detect disease at early stages have a great impact on prevalence and treatment outcomes. More importantly, advancing technology may provide an opportunity to capture early events and processes previously unrecognized, thus perhaps creating unique treatment options.

Extracellular Matrix

The extracellular matrix “glue” is an amorphous mixture of various cellular and non-cellular elements critical to myelomagenesis. Comprised and supported by non-hematopoietic cellular components (stromal cells, fibroblasts, adipocytes, osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and endothelial cells), the bone marrow extracellular matrix contains soluble factors (cytokines and growth factors) and non-soluble factors (fibrous proteins, glycosaminoglycans, proteoglycans, and SIBLING proteins). It propagates myelomagenesis by modulating cytokine and growth factor cross-talk, homing and adhesion of tumor cells to surrounding substrate, and facilitating angiogenesis. Most studies characterizing these processes in MM have been conducted in later disease states, where tumor growth has already accelerated and architecture is distorted. Capturing and defining these processes at earlier pathological stages may have a meaningful impact on disease evolution.

Cytokines and Growth Factors

Malignant myeloma plasma cells rely on a number of growth factors and cytokines for proliferation and survival. These include IL-6, SDF-1, MIP-1, IL-10, IGF-1, FGF, VEGF, HGF, Wnt-family members, and others. Utilizing Affymetrix RNA microarrays, a recent study confirms that most myeloma growth factors are derived from extracellular matrix cells such as stromal cells and osteoblasts rather than malignant myeloma cells themselves [21, 22]. Many of these same growth factors and receptors are also overexpressed in microenvironments containing normal differentiating plasma cells [22]. Distinguishing patterns of growth factor and receptor expression between precursor MGUS and malignant MM states may help elucidate early pathogenetic events.

Although required for normal plasma cell differentiation, serum levels of IL-6 correlate with disease severity and increase from MGUS to early MM to late stage MM [23, 24]. In addition, autocrine production of IL-6 has been noted in immature CD45+ MM cells [25]. A potent activator of MAPK, JAK/STAT, and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways, IL-6 is required by most MM tumor cell lines for generation of various anti-apoptotic transcription factors (Mcl-1, bcl-2, bcl-xl, c-myc) and induction of plasma cell differentiation factors (Blimp-1, IRF4 and XBP-1) [26-28]. The sequence of transcription factor expression during MM pathogenesis has not been clearly characterized; however, their overproduction strongly correlates with the presence of malignant plasma cells, likely reflecting changes in survival mechanisms in these cells. However, several tumor cell lines grow independently of IL-6, suggesting that alternative critical signaling pathways are also involved.

Homing and Adhesion

It is becoming increasingly clear that homing and adhesive molecules mediate crucial signaling between MM cells and their surrounding environment. Recent studies have shown that these molecules cue tumor proliferation, response and adaption. Given that normal plasma cells reside in the bone marrow, it remains unclear whether a unique “malignant” MM surface cell phenotype is required for initial establishment of neoplastic cells in the marrow.

MM cells have similar homing patterns to normal mature long lived plasma cells [29]. CXCR-4, the chemokine receptor for SDF-1, is upregulated on normal differentiating mature plasma cells [29, 30]. In lieu of elevated SDF-1 levels found in MM bone marrow, the SDF-1/CXCR-4 interaction could be an exaggerated response of a normal process [31, 32]. Binding of α4β1 integrin on MM to extracellular VCAM-1 and fibronectin is a similar example of a critical interaction found in normal homing plasma cells that could be embellished due to high levels of IGF-1 and other chemoattractants found in MM [33]. Blocking the α4β1 integrin interaction with antibody disturbs adhesion, transmigration, and growth of MM tumor cells [34].

Certainly, interactions between myeloma cells and extracellular matrix are dynamic during the disease course. Changes in extracellular matrix are mediated by degrading proteins, such as metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) and correlate with disease progression [35]. Bone marrow extracellular matrix from MM and MGUS patients compared to normal marrow expresses similar amounts of laminin, lower quantities of fibronectin, collagen type-I, and higher quantities of collagen type-IV [36]. In parallel, the receptor for fibronectin found on the surface of normal plasma cells, α5β1 integrin, decreases as MM progresses into aggressive extramedullary disease states [37].

Other components of the extracellular matrix playing a role in MM pathogenesis include proteoglycans, glycosaminoglycans and SIBLING proteins. Proteoglycans are protein cores with attached glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) found in the extracellular matrix and involved in supporting an electrostatic microenvironment, molecule trafficking, and growth factor regulation. Syndecan 1 or CD138 is a transmembrane heparan sulfate-bearing proteoglycan found on the surface of benign and malignant plasma cells. Newly diagnosed untreated MM patients demonstrate higher levels of plasma syndecan-1 compared to MGUS patients likely due to disease burden [38]. Remodeling or shedding of syndecan-1 is modulated by heparanase, a heparan-GAG cleaving enzyme also found to be elevated in aggressive MM phenotypes [39]. Shed syndecan-1 accumulates in later disease states in areas of fibrosis around the bone [40]. Distribution of syndecan-1 likely contributes to progressive disease states by co-localizing MM cells to essential growth factors (HGF, VEGF, heparin binding EGF proteins) and approximating physical interaction.

Angiogenesis

Neovascularization is a prominent feature associated with high grade disease in several malignancies, and MM seems to be no exception. Increasing microvessel density (MVD) within myeloma microenvironment correlates with prognosis and severity of disease across the spectrum of plasma cell dyscrasias [41-44]. Certainly, marrow microenvironment of MM patients is enriched with potent pro-angiogenic stimulators, such as VEGF, SDF-1, HGF, FGF and others [43, 45]. Stromal cells and IL-6-dependent plasma cells secrete VEGF and stimulate endothelial cells to form new vessels [46]. VEGF receptors can also be found on the surface of stromal cells and MM cells, suggesting autocrine and paracrine feedback mechanisms. Studies confirm higher levels of VEGF expression from MM patients compared to MGUS/SMM patients [47, 48].

Murine model studies, 5T2MM, indicate there may be an “angiogenic switch” that occurs during early myelomagenesis, just prior to neovascularization acceleration, where 5T2MM cell phenotypes change from being CD45+ to CD45−. CD45− 5T2MM cells produce increased levels of VEGF compared to CD45+ 5T2MM cells [49]. Correlative studies in humans confirm this inverse relationship between CD45+ MM cells and degree of angiogenesis. Interestingly, subsets of VEGF receptor expression on MM cells do not seem to vary among disease groups from MGUS to MM, but rather they are preferentially expressed on CD45+ plasma cell subsets [48]. Increased VEGF receptors seen on these CD45+ plasma cells compared to CD45− plasma cells may indicate an early inhibitory feedback mechanism that is lost in progressive stages of disease.

Dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI) is a sensitive clinical tool that detects changes in microcirculation of bone marrow. These changes can be detected as early as in asymptomatic MGUS and SMM disease states [50]. More importantly, as remodeling of the vasculature becomes further characterized, application of these clinical techniques may create opportunities for detection and application of anti-angiogenic treatment strategies.

Immune-dysregulation

Evasion of the immune system may be a driving factor of malignant transformation from MGUS to MM. The notion that pre-malignant disease may undergo “immunoediting” is not unique to MM and its precursor state of MGUS. Such a process first involves a heightened state of “immunosurveillance” in MGUS, where tumor suspects are sought and destroyed, followed by “equilibrium”, and “escape” of the tumor clone capable of avoiding defense mechanisms [51]. Studies investigating T cells, NK cells, tumor specific antigens and other immunological parameters confirm fundamental differences in adaptive and innate host immune strategies between healthy controls, MGUS and MM patients. Again, defining these processes during precursor MGUS disease states may allow adoption of immunotherapy as a novel disease preventive tactic.

Clonal plasma cells participate in regulating their immune environment as early as MGUS. Compared to normal plasma cells, clonal MGUS plasma cells demonstrate increased HLA-1 and co-stimulatory molecules on the cell surface [52]. However, conflicting reports exist on whether plasma cell surface HLA-1 expression increases or decreases as MGUS transitions to MM [52, 53]. Progressive disease may be marked by soluble increases of HLA-1 and β2 microglobulin in plasma of MM patients rather than their cells’ surface, perhaps further impairing immune responses by increasing NK and T cell apoptosis [52, 54, 55]. Such variable HLA-1 expression may be attributed to altered expression patterns of antigen processing machinery in plasma cells [56].

Global immune dysfunction seems to persist with respect to other cell populations, including CD8 T cells and NK cells. Likely representing evidence of an anti-tumor immune response, oligoclonal CD8 T cell expansions can be found in both MGUS and MM. In fact, low disease burden states, such as MGUS and Stage I MM may demonstrate more robust CD8 T cell expansions [57, 58]. Cellular immunity demonstrated in MGUS directed against SOX-2, a gene involved in embryonal self-renewal, may play a role in keeping pre-malignant clonal plasma cells in balance [59]. However, as disease progresses from benign to malignant, these same immune cell populations demonstrate deranged functional activity. CD 8 T cells isolated from bone marrows from MGUS patients show rapid effector T cell responses against pre-malignant autologous plasma cells compared to MM blunted responses [60, 61]. Similarly, MM NK cells produce decreased amounts of IFN-γ and exhibit functional defective characteristics compared to NK cells found in MGUS [62]. NK cell mediated death is largely mediated by activating receptor NKG2D. Decreased NK cell toxicity could be related to increased inhibitory signals directed against NKG2D receptors by ligands such as MHC class 1 related protein (MICA/B) or downregulation of death receptor Fas (CD95) on myeloma cells [63, 64].

Summary and Conclusions

Systematic evaluation of pathogenetic differences between MGUS and MM should offer invaluable insights into early myelomagenesis. At present, we know that virtually all MM are preceded by MGUS, but we also know that most patients with MGUS will not develop MM. Early identification of MGUS patients who will progress to MM is currently a diagnostic challenge that needs additional studies. Multiple pathogenetic mechanisms have been proposed to play a role in disease progression. Understanding the events leading to end-organ damage and development of more precise diagnostic criteria of disease progression are critical parts of investigation of early pathogenesis of myeloma and should provide us with better tools for early identification and treatment of patients who will transition from MGUS to MM. Emphasis should be placed on comprehensive studies that probe not just tumor plasma cells but their microenvironment interactions as well. Dynamic changes in tumor and microenvironment, cell immunophenotype, mRNA and protein expression should offer insight into disease progression. Extracellular matrix restructuring, angiogenesis establishment, and immune system evasion all seem to be processes firmly demonstrated in malignant MM phenotypes, but not as readily identified in MGUS. With the development of better diagnostic techniques and application of therapeutics at earlier stages, prognosis of MM can hopefully be changed in the future by delaying or eradicating end stage disease.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Waldron W, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2007. 2010 based on 2009 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/

- 2.Landgren O, Kyle RA, Pfeiffer RM, Katzmann JA, Caporaso NE, Hayes RB, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) consistently precedes multiple myeloma: a prospective study. Blood. 2009;113(22):5412–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-194241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fonseca R, Bergsagel PL, Drach J, Shaughnessy J, Gutierrez N, Stewart AK, et al. International Myeloma Working Group molecular classification of multiple myeloma: spotlight review. Leukemia. 2009;23(12):2210–21. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Rajkumar SV, Offord JR, Larson DR, Plevak MF, et al. A long-term study of prognosis in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(8):564–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa01133202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKenna RW, Kyle RA, Kuehl WM, Grogan TM, Harris NL, Coupland RW. Plasma Cell Neoplasms. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic Lymphoid Tissues. 2008:200–13. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Criteria for the classification of monoclonal gammopathies, multiple myeloma and related disorders: a report of the International Myeloma Working Group. Br J Haematol. 2003;121(5):749–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Rajkumar SV, Larson DR, Plevak MF, Offord JR, et al. Prevalence of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(13):1362–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajkumar SV, Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Melton LJ, 3rd, Bradwell AR, Clark RJ, et al. Serum free light chain ratio is an independent risk factor for progression in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Blood. 2005;106(3):812–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kyle RA, Remstein ED, Therneau TM, Dispenzieri A, Kurtin PJ, Hodnefield JM, et al. Clinical course and prognosis of smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(25):2582–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riccardi A, Ucci G, Luoni R, Castello A, Coci A, Magrini U, et al. Bone marrow biopsy in monoclonal gammopathies: correlations between pathological findings and clinical data. The Cooperative Group for Study and Treatment of Multiple Myeloma. J Clin Pathol. 1990;43(6):469–75. doi: 10.1136/jcp.43.6.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perez-Persona E, Vidriales MB, Mateo G, Garcia-Sanz R, Mateos MV, de Coca AG, et al. New criteria to identify risk of progression in monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance and smoldering multiple myeloma based on multiparameter flow cytometry analysis of bone marrow plasma cells. Blood. 2007;110(7):2586–92. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-088443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin P, Owens R, Tricot G, Wilson CS. Flow cytometric immunophenotypic analysis of 306 cases of multiple myeloma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121(4):482–8. doi: 10.1309/74R4-TB90-BUWH-27JX. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kraj M, Sokolowska U, Kopec-Szlezak J, Poglod R, Kruk B, Wozniak J, et al. Clinicopathological correlates of plasma cell CD56 (NCAM) expression in multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49(2):298–305. doi: 10.1080/10428190701760532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silvestris F, Tucci M, Cafforio P, Dammacco F. Fas-L up-regulation by highly malignant myeloma plasma cells: role in the pathogenesis of anemia and disease progression. Blood. 2001;97(5):1155–64. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.5.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maes K, Nemeth E, Roodman GD, Huston A, Esteve F, Freytes C, et al. In anemia of multiple myeloma, hepcidin is induced by increased bone morphogenetic protein 2. Blood. 2010 doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-274571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kristinsson SY, Tang M, Pfeiffer RM, Bjorkholm M, Blimark C, Mellqvist UH, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and risk of skeletal fractures: a population-based study. Blood. 2010;116(15):2651–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-282848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bataille R, Chappard D, Basle MF. Quantifiable excess of bone resorption in monoclonal gammopathy is an early symptom of malignancy: a prospective study of 87 bone biopsies. Blood. 1996;87(11):4762–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Politou M, Terpos E, Anagnostopoulos A, Szydlo R, Laffan M, Layton M, et al. Role of receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand (RANKL), osteoprotegerin and macrophage protein 1-alpha (MIP-1a) in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) Br J Haematol. 2004;126(5):686–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bataille R, Chappard D, Marcelli C, Dessauw P, Baldet P, Sany J, et al. Recruitment of new osteoblasts and osteoclasts is the earliest critical event in the pathogenesis of human multiple myeloma. J Clin Invest. 1991;88(1):62–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI115305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaiser M, Mieth M, Liebisch P, Oberlander R, Rademacher J, Jakob C, et al. Serum concentrations of DKK-1 correlate with the extent of bone disease in patients with multiple myeloma. Eur J Haematol. 2008;80(6):490–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2008.01065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klein B, Zhang XG, Jourdan M, Content J, Houssiau F, Aarden L, et al. Paracrine rather than autocrine regulation of myeloma-cell growth and differentiation by interleukin-6. Blood. 1989;73(2):517–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahtouk K, Moreaux J, Hose D, Reme T, Meissner T, Jourdan M, et al. Growth factors in multiple myeloma: a comprehensive analysis of their expression in tumor cells and bone marrow environment using Affymetrix microarrays. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:198. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaillard JP, Bataille R, Brailly H, Zuber C, Yasukawa K, Attal M, et al. Increased and highly stable levels of functional soluble interleukin-6 receptor in sera of patients with monoclonal gammopathy. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23(4):820–4. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bataille R, Jourdan M, Zhang XG, Klein B. Serum levels of interleukin 6, a potent myeloma cell growth factor, as a reflect of disease severity in plasma cell dyscrasias. J Clin Invest. 1989;84(6):2008–11. doi: 10.1172/JCI114392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hata H, Xiao H, Petrucci MT, Woodliff J, Chang R, Epstein J. Interleukin-6 gene expression in multiple myeloma: a characteristic of immature tumor cells. Blood. 1993;81(12):3357–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein B, Tarte K, Jourdan M, Mathouk K, Moreaux J, Jourdan E, et al. Survival and proliferation factors of normal and malignant plasma cells. Int J Hematol. 2003;78(2):106–13. doi: 10.1007/BF02983377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jourdan M, Veyrune JL, De Vos J, Redal N, Couderc G, Klein B. A major role for Mcl-1 antiapoptotic protein in the IL-6-induced survival of human myeloma cells. Oncogene. 2003;22(19):2950–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moreaux J, Legouffe E, Jourdan E, Quittet P, Reme T, Lugagne C, et al. BAFF and APRIL protect myeloma cells from apoptosis induced by interleukin 6 deprivation and dexamethasone. Blood. 2004;103(8):3148–57. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pals ST, de Gorter DJ, Spaargaren M. Lymphoma dissemination: the other face of lymphocyte homing. Blood. 2007;110(9):3102–11. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-075176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hargreaves DC, Hyman PL, Lu TT, Ngo VN, Bidgol A, Suzuki G, et al. A coordinated change in chemokine responsiveness guides plasma cell movements. J Exp Med. 2001;194(1):45–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gazitt Y, Akay C. Mobilization of myeloma cells involves SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling and downregulation of VLA-4. Stem Cells. 2004;22(1):65–73. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-1-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zannettino AC, Farrugia AN, Kortesidis A, Manavis J, To LB, Martin SK, et al. Elevated serum levels of stromal-derived factor-1alpha are associated with increased osteoclast activity and osteolytic bone disease in multiple myeloma patients. Cancer Res. 2005;65(5):1700–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tai YT, Podar K, Catley L, Tseng YH, Akiyama M, Shringarpure R, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-1 induces adhesion and migration in human multiple myeloma cells via activation of beta1-integrin and phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase/AKT signaling. Cancer Res. 2003;63(18):5850–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mori Y, Shimizu N, Dallas M, Niewolna M, Story B, Williams PJ, et al. Anti-alpha4 integrin antibody suppresses the development of multiple myeloma and associated osteoclastic osteolysis. Blood. 2004;104(7):2149–54. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vacca A, Ribatti D, Presta M, Minischetti M, Iurlaro M, Ria R, et al. Bone marrow neovascularization, plasma cell angiogenic potential, and matrix metalloproteinase-2 secretion parallel progression of human multiple myeloma. Blood. 1999;93(9):3064–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tancred TM, Belch AR, Reiman T, Pilarski LM, Kirshner J. Altered expression of fibronectin and collagens I and IV in multiple myeloma and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. J Histochem Cytochem. 2009;57(3):239–47. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2008.952200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pellat-Deceunynck C, Barille S, Puthier D, Rapp MJ, Harousseau JL, Bataille R, et al. Adhesion molecules on human myeloma cells: significant changes in expression related to malignancy, tumor spreading, and immortalization. Cancer Res. 1995;55(16):3647–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scudla V, Pika T, Budikova M, Petrova J, Minarik J, Bacovsky J, et al. The importance of serum levels of selected biological parameters in the diagnosis, staging and prognosis of multiple myeloma. Neoplasma. 2010;57(2):102–10. doi: 10.4149/neo_2010_02_102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Purushothaman A, Chen L, Yang Y, Sanderson RD. Heparanase stimulation of protease expression implicates it as a master regulator of the aggressive tumor phenotype in myeloma. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(47):32628–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806266200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bayer-Garner IB, Sanderson RD, Dhodapkar MV, Owens RB, Wilson CS. Syndecan-1 (CD138) immunoreactivity in bone marrow biopsies of multiple myeloma: shed syndecan-1 accumulates in fibrotic regions. Mod Pathol. 2001;14(10):1052–8. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swelam WM, Al Tamimi DM. Biological impact of vascular endothelial growth factor on vessel density and survival in multiple myeloma and plasmacytoma. Pathol Res Pract. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Munshi NC, Wilson C. Increased bone marrow microvessel density in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma carries a poor prognosis. Semin Oncol. 2001;28(6):565–9. doi: 10.1016/s0093-7754(01)90025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi JH, Ahn MJ, Jang SJ, Park CK, Park YW, Oh HS, et al. Absence of clinical prognostic value of vascular endothelial growth factor and microvessel density in multiple myeloma. Int J Hematol. 2002;76(5):460–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02982812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rajkumar SV, Mesa RA, Fonseca R, Schroeder G, Plevak MF, Dispenzieri A, et al. Bone marrow angiogenesis in 400 patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, multiple myeloma, and primary amyloidosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(7):2210–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martin SK, Dewar AL, Farrugia AN, Horvath N, Gronthos S, To LB, et al. Tumor angiogenesis is associated with plasma levels of stromal-derived factor-1alpha in patients with multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(23):6973–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dankbar B, Padro T, Leo R, Feldmann B, Kropff M, Mesters RM, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor and interleukin-6 in paracrine tumor-stromal cell interactions in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2000;95(8):2630–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vacca A, Ria R, Ribatti D, Semeraro F, Djonov V, Di Raimondo F, et al. A paracrine loop in the vascular endothelial growth factor pathway triggers tumor angiogenesis and growth in multiple myeloma. Haematologica. 2003;88(2):176–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kimlinger T, Kline M, Kumar S, Lust J, Witzig T, Rajkumar SV. Differential expression of vascular endothelial growth factors and their receptors in multiple myeloma. Haematologica. 2006;91(8):1033–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Asosingh K, De Raeve H, Menu E, Van Riet I, Van Marck E, Van Camp B, et al. Angiogenic switch during 5T2MM murine myeloma tumorigenesis: role of CD45 heterogeneity. Blood. 2004;103(8):3131–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hillengass J, Zechmann C, Bauerle T, Wagner-Gund B, Heiss C, Benner A, et al. Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging identifies a subgroup of patients with asymptomatic monoclonal plasma cell disease and pathologic microcirculation. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(9):3118–25. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dunn GP, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. The immunobiology of cancer immunosurveillance and immunoediting. Immunity. 2004;21(2):137–48. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perez-Andres M, Almeida J, Martin-Ayuso M, Moro MJ, Martin-Nunez G, Galende J, et al. Clonal plasma cells from monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, multiple myeloma and plasma cell leukemia show different expression profiles of molecules involved in the interaction with the immunological bone marrow microenvironment. Leukemia. 2005;19(3):449–55. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bernal M, Garrido P, Jimenez P, Carretero R, Almagro M, Lopez P, et al. Changes in activatory and inhibitory natural killer (NK) receptors may induce progression to multiple myeloma: implications for tumor evasion of T and NK cells. Hum Immunol. 2009;70(10):854–7. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spaggiari GM, Contini P, Dondero A, Carosio R, Puppo F, Indiveri F, et al. Soluble HLA class I induces NK cell apoptosis upon the engagement of killer-activating HLA class I receptors through FasL-Fas interaction. Blood. 2002;100(12):4098–107. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Puppo F, Contini P, Ghio M, Brenci S, Scudeletti M, Filaci G, et al. Soluble human MHC class I molecules induce soluble Fas ligand secretion and trigger apoptosis in activated CD8(+) Fas (CD95)(+) T lymphocytes. Int Immunol. 2000;12(2):195–203. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Racanelli V, Leone P, Frassanito MA, Brunetti C, Perosa F, Ferrone S, et al. Alterations in the antigen processing-presenting machinery of transformed plasma cells are associated with reduced recognition by CD8+ T cells and characterize the progression of MGUS to multiple myeloma. Blood. 2010;115(6):1185–93. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-228676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Perez-Andres M, Almeida J, Martin-Ayuso M, Moro MJ, Martin-Nunez G, Galende J, et al. Characterization of bone marrow T cells in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, multiple myeloma, and plasma cell leukemia demonstrates increased infiltration by cytotoxic/Th1 T cells demonstrating a squed TCR-Vbeta repertoire. Cancer. 2006;106(6):1296–305. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Halapi E, Werner A, Wahlstrom J, Osterborg A, Jeddi-Tehrani M, Yi Q, et al. T cell repertoire in patients with multiple myeloma and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: clonal CD8+ T cell expansions are found preferentially in patients with a low tumor burden. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27(9):2245–52. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spisek R, Kukreja A, Chen LC, Matthews P, Mazumder A, Vesole D, et al. Frequent and specific immunity to the embryonal stem cell-associated antigen SOX2 in patients with monoclonal gammopathy. J Exp Med. 2007;204(4):831–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dhodapkar MV, Krasovsky J, Olson K. T cells from the tumor microenvironment of patients with progressive myeloma can generate strong, tumor-specific cytolytic responses to autologous, tumor-loaded dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(20):13009–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202491499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dhodapkar MV, Krasovsky J, Osman K, Geller MD. Vigorous premalignancy-specific effector T cell response in the bone marrow of patients with monoclonal gammopathy. J Exp Med. 2003;198(11):1753–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dhodapkar MV, Geller MD, Chang DH, Shimizu K, Fujii S, Dhodapkar KM, et al. A reversible defect in natural killer T cell function characterizes the progression of premalignant to malignant multiple myeloma. J Exp Med. 2003;197(12):1667–76. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.von Lilienfeld-Toal M, Frank S, Leyendecker C, Feyler S, Jarmin S, Morgan R, et al. Reduced immune effector cell NKG2D expression and increased levels of soluble NKG2D ligands in multiple myeloma may not be causally linked. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2010;59(6):829–39. doi: 10.1007/s00262-009-0807-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jinushi M, Vanneman M, Munshi NC, Tai YT, Prabhala RH, Ritz J, et al. MHC class I chain-related protein A antibodies and shedding are associated with the progression of multiple myeloma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(4):1285–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711293105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]