Abstract

Pancreatic islets contain low activities of catalase, selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPX1), and Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1). Thus, enhancing expression of these enzymes in islets has been unquestionably favored. However, such an attempt has produced variable metabolic outcomes. While β cell-specific overexpression of Sod1 enhanced mouse resistance to streptozotocin-induced diabetes, the same manipulation of catalase aggravated onset of type 1 diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. Global overexpression of Gpx1 in mice induced type 2 diabetes-like phenotypes. Although knockouts of Gpx1 and Sod1 each alone or together decreased pancreatic β cell mass and plasma insulin concentrations, these knockouts improved body insulin sensitivity to different extents. Pancreatic duodenal homeobox 1, forkhead box A2, and uncoupling protein 2 are three key regulators of β cell mass, insulin synthesis, and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Phenotypes resulted from altering GPX1 and/or SOD1 were partly mediated through these factors, along with protein kinase B and c-jun terminal kinase. A shifted reactive oxygen species inhibition of protein tyrosine phosphatases in insulin signaling might be attributed to altered insulin sensitivity. Overall, metabolic roles of antioxidant enzymes in β cells and diabetes depend on body oxidative status and target functions. Revealing regulatory mechanisms for this type of dual role will help prevent potential pro-diabetic risk of antioxidant over-supplementation to humans. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 14, 489–503.

Introduction

Millions of people in the United States and elsewhere suffer from type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes. In fact, type 2 diabetes is becoming an epidemic disease that afflicts 10%–25% of the population. Pathologically, type 1 diabetes is characterized by destruction of pancreatic islet β cells, loss of insulin synthesis, and failure of glycemic control. Its development is incited by genetic predisposition and environmental factors, including reactive oxygen species (ROS) or oxidative stress (102). Insulin resistance is a hallmark and a key factor in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes (28). Although development of overt type 2 diabetes from insulin-resistant state may take a long time due to an initial increase in islet β cell mass and(or) function, an eventual failure of this compensation leads to impaired β cell functions and body glucose homeostasis. The turning point and the underlying mechanism still remain a challenging question.

Earlier, ROS was implicated only in complications of type 2 diabetes. However, evidence has been accumulated for a causal role of oxidative stress in inducing insulin resistance before the onset of diabetes (15). In cultured 3T3-L adipocytes (114) and L6 muscle cells (8), H2O2 decreased insulin-mediated glucose uptake, glycogen synthesis, Glut 4 transportation, and phosphorylation of insulin signaling proteins. In humans, oxidative stress has been shown to be associated with adiposity and insulin resistance (62). Likewise, ROS production in adipose tissue of obese mice was accompanied by augmented expression of NADPH oxidase and decreased expression of antioxidant enzymes (35). In skeletal muscle, oxidative stress caused substantial insulin resistance in distal insulin signaling and glucose transport activity (5). A recent genomic analysis of cytokine- and glucocorticoid-induced insulin resistance revealed a common role of ROS in developing this disorder (50). Because of those involvements of oxidative stress in both type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes, antioxidant enzymes and antioxidant nutrients have been thought to protect against diabetes. However, findings from a number of recent animal and human studies strongly challenge this prevailing paradigm.

Perceived Susceptibility of β Cells to Oxidative Stress

Like most living organisms on the Earth, mammals, including humans, use energy mainly produced by coupled reactions of respiration and oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria. According to Mitchell's chemiosmotic theory, ATP synthesis links with mitochondrial membrane potential (96). The system is reversible by uncouplers of respiration and oxidative phosphorylation such as 2,4-dinitrophenol. However, mitochondrial respiration generates not only ATP but also free radicals. Because those molecules have one or more unpaired electrons in certain atoms such as oxygen or nitrogen and usually seek other electrons to become paired, they are highly reactive or destructive to attack other molecules. Hydroxyl radical, superoxide, and hydrogen and lipid peroxides are often considered to be main forms of metabolically derived ROS. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite are the main forms of reactive nitrogen species (RNS). Despite recent discovery of dual roles of H2O2 derived from glucose metabolism in insulin secretion and β cell integrity (108), ROS and RNS have been largely perceived to be detrimental to β cells and insulin function.

Mammals have evolved with three cellular antioxidant defense systems to cope with ROS and RNS. These include (a) low-molecular-mass antioxidants such as GSH, uric acid, and vitamins C and E; (b) antioxidant enzymes; and (c) sequestration and repairing systems. Although all three protective systems are important and interdependent, this review focuses on only antioxidant enzymes. As widely accepted, catalase, glutathione peroxidase (GPX), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) represent the three most important intracellular antioxidant enzymes. Among the six forms of selenium (Se)-dependent GPX, GPX1 was the first identified and most abundant selenoprotein. Located in both cytosol and mitochondria (26), GPX1 accounts for over 90% of the total GPX activity in most tissues (19), and utilizes GSH to reduce H2O2 and other organic hydroperoxides. Due to this biochemical function, GPX1 was initially considered to be a major intracellular antioxidant enzyme in vivo. Later, that presumed function was questioned because of its high tissue abundance, extreme responsiveness to Se supply, and low ranking in acquiring Se in Se deficiency (125). Recent research using the Gpx1 knockout (Gpx1−/−) and overexpressing Gpx1 (OE) mice has demonstrated that normal Gpx1 expression is essential, and overexpression of Gpx1 is beneficial for protection against acute oxidative stress induced by ROS (20). However, GPX1 actually potentiates toxicities of drugs that induce formation of peroxynitrite (34, 95). There are three forms of SOD: SOD1, Cu,Zn-SOD; SOD2, Mn-SOD; and SOD3, extracellular SOD3. SOD1 comprises over 90% of the total cellular SOD activity, and functions upstream of GPX1 in catalyzing dismutation of O2• into H2O2. Likewise, knockout of Sod1 alone or together with Gpx1 actually protected mice against acetaminophen-induced lethality and hepatic protein nitration (146). Catalase shares a common substrate of H2O2 with GPX1, but with a higher km. In addition, glutathione reductase, thiodoxin reductase, and glutathione S-transferase are also detected in islets.

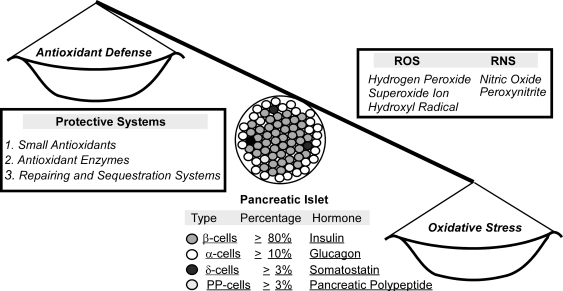

Pancreatic islets of Langerhans represent a main structure to regulate glucose metabolism and homeostasis. Representing the major portion of islets, β cells synthesize and secrete insulin. There are also three other types of endocrine cells to produce three different hormones, respectively (Fig. 1). Compared with liver, islets contain only 1% catalase, 2% GPX1, and 29% SOD1 activities (40, 80, 130). Thus, β cells are considered to be low in antioxidant defense and susceptible to oxidative stress. Significant differences in allele and genotype distribution in Sod1 and Sod2 genes (but not in catalase gene) were found among type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes, and control subjects (33). In a large Japanese cohort, GPX1 Pro198Leu variant was found to contribute to the metabolic syndrome in men, but not in women (74). Earlier work in the 1990s showed that loss of pancreatic GPX activity was often associated with islet dysfunction (6). In fact, β cells are a primary target of diabetogenic agents streptozotocin (STZ) and alloxan that generates H2O2 (84, 126). Loss of β cell mass has been recognized as a pivotal factor in pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes (109). Most individuals with type 2 diabetes show a net decrease of β cell mass, whereas obese individuals who develop insulin resistance but not type 2 diabetes exhibit an increased β cell mass for the compensatory insulin synthesis and secretion (13). Pancreatic β cell mass is primarily regulated by replication and apoptosis (109). Transcriptional factors pancreatic duodenal homeobox 1 (PDX1) plays a pivotal role in proliferation, survival, and function of β cells and activation of insulin gene expression (3, 145). Meanwhile, β cell apoptosis in diabetic subjects is a more deciding factor than replication compared with control subjects (13). This event can be triggered by high glucose (30) and cytokines that induce ROS and RNS formations (91).

FIG. 1.

Overview of endocrine cell types and functions, main forms of ROS and RNS, and antioxidant defense systems in pancreatic islets. The tilted balance scale symbolizes a perceived susceptibility of β cells to ROS or oxidative stress due to relatively low activity of antioxidant enzymes. RNS, reactive nitrogen species; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

The well-known harmful effect of hyperglycemia or glucose toxicity has long been recognized to be mediated by oxidative stress. Exposure of RIN 1046-38 β cells with increased glucokinase activity to 20 mM glucose resulted in decreases of NADP(H) and ATP levels, accumulation of ROS, damages of mitochondria and DNA, and apoptosis (140). A superoxide-related pathway was proposed to account for ATP decreases in hyperinsulinemia-induced β cell dysfunction (69). However, exposing β cells isolated from rat to 20 mM glucose did not increase H2O2 or superoxide production, but led to a dose-dependent increase in NADP(H) and FADH2 levels (92). Treating the RIN 1046-38 β cells with normal glucokinase activity with high glucose failed to induce excessive ROS production (140). These discrepancies underscore functional complexity of ROS and antioxidant enzymes in β cell integrity and glucose metabolism.

Crucial Roles of PDX1 and Forkhead Box A2 in β cells and Insulin Synthesis

Pancreatic duodenal homeobox 1

Discovered in 1993 as a regulator of insulin and somatostatin promoters (81), PDX1 (IPF1 in humans) has been shown to be responsible for defective insulin secretion and development of maturity onset type of diabetes (MODY 4) (120, 121). It is a key factor in defining the fate of exocrine and endocrine pancreas development, and plays a pivotal role in pancreatic β cell differentiation and insulin gene expression (3, 56, 120). Insulin is synthesized in significant quantities only in islet β cells, and its mRNA is translated as a single chain precursor called preproinsulin. After removal of the signal peptide and entering the endoplasmic reticulum, pro-insulin is produced for secretion. In the process of insulin gene expression, PDX1 binds to the insulin promoter at three sites: A1, A3, and A5. Under glucose toxicity, Pdx1 gene expression is inhibited by posttranscriptional defect and distorted binding of PDX1 protein to the insulin gene promoter (112). In addition, PDX1 regulates expression of hundreds of other genes related to glucose metabolism. Using promoter microarrays, Keller and associates identified 583 new PDX1 target genes (65). A close analysis of 31 proteins encoded by these PDX1 target genes indicated that 29 of those were expressed in β cells, and 68% of which was up- or downregulated by dominant negative mutation in Pdx1 (65).

PDX1 plays an important role in β cell proliferation, neogenesis, and apoptosis. In C57BL/6 mice, a 60% pancreatectomy resulted in a progressive β cell mass increase within 2 weeks, and the increase was correlated with activation of Pdx1 expression (107). Similarly, β cell mass or islet number in Pdx1+/− mice failed to increase with age, and became 50% less than the wild type (WT) at 1 year old (54). Clearly, loss of Pdx1 expression is associated with increased apoptosis and decreased regeneration of progressive β cells. Islets and dispersed β cells from Pdx1+/− mice were more susceptible to apoptosis at baseline glucose concentrations than those of Pdx1+/+. An increased apoptosis in vivo in these mice was associated with abnormal islet architecture, positive TUNEL, active caspase-3, and lymphocyte infiltration (54). Moreover, pro-survival effects of insulin largely disappeared in islets with 50% PDX1 deficiency, which provided direct evidence that PDX1 was a signaling target of insulin (53). In rodent models of pancreatic injury, Pdx1 expression was related to β cell neogenesis (116). Upregulation of PDX1 by a glucagon-like peptide 1 analog exendin-4 was followed by islet proliferation and islet to ductal trans-differentiation in partially pancreatectomized rats (29). PDX1 inhibits expression of glucagon gene that is mainly expressed in islet α cells, implying a cross control by a molecule from a different type of cells (49).

PDX1 also plays a crucial role in functioning of adult pancreas. It remains active in mature β cells through adulthood (103). In adult subjects, PDX1 is essential for normal pancreatic islet function by regulating expression of a number of pancreatic genes, including insulin, somatostatin, islet amyloid polypeptide, glucose transporter type 2, and glucokinase (51). Mice with 50% PDX1 had worsening glucose tolerance with age and reduced insulin release in response to glucose, KCl, and arginine from the perfused pancreas (54). Transcription of Pdx1 in mice was reversibly repressed by administration of doxycycline, and the resultant impairments in insulin and glucagon expression led to diabetes within 14 days (49). However, withdrawal of doxycycline de-repressed Pdx1 expression and restored normoglycemia within 28 days. Most importantly, ROS or oxidative stress affects expression and function of Pdx1 at epigenetic, transcriptional, and posttranslational levels (see below).

Forkhead box A2

Previously known as HNF3β, forkhead box A2 (FOXA2) is an extremely important transcriptional factor from the Fox gene family that contains more than 40 conserved proteins with DNA-binding domain called forkhead box (57). These proteins are involved in organogenesis and regulation of multiple functions in adulthood. One of the most important functions for FOXA2 is to activate insulin gene expression by binding to the Pdx1 promoter (77). It also controls vesicle docking and insulin secretion in mature β cells (37). Simultaneous ablation of Foxa2 with Foxa1 that cooccupies regulatory sites of Pdx1 completely blocked Pdx1 expression (36). A pancreas-specific ablation of Foxa2 led to deregulated insulin secretion and hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia (124). A FOXA ortholog (PHA-4) was involved in diet restriction-mediated longevity in C. elegans (105). At the same time, FOXA2 was also noticed as a regulator of insulin sensitivity as well as hepatic lipid metabolism and ketogenesis in fasting state and type 2 diabetes (138, 144). Reduced, oxidized, or total hepatic glutathione concentrations were decreased in Foxa2 mutant mice fed a cholic acid diet compared with the WT controls (11). The Sod1 promoter contains four consensus PHA-4 (FOXA) binding sites (14), and knockout of Sod1 downregulated Foxa2 expression and function (see below).

Uncoupling Protein 2 and Mitochondria in Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion

Classic scheme of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) depends on a high ATP/ADP ratio in β cells by glucose oxidation (143). Glucose metabolism in islets starts at glucose uptake by GLUT2, followed by the glucokinase-mediated phsophorylation and oxidation to produce ATP. The generated ATP molecules first bind to the ATP-binding cassette of SUR1 subunit of KATP-dependent potassium channels, and then cause closing of its second subunit potassium inward rectifier channels (KIR6.2). Consequently, intracellular concentration of potassium ions is increased followed by cell membrane depolarization and opening of voltage-dependent calcium channels. The resultant inward Ca2+ flux triggers in exocytosis of stored insulin. As a natural uncoupler of respiration and oxidative phosphorylation, uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) is expressed in islet β cells (38) and is considered to be a negative regulator of insulin release (143). UCP2 is activated by endogenously produced superoxide (69) and can in turn modulate mitochondrial generation of H2O2 (100). Thus, UCP2 may serve as a link between intracellular oxidant/antioxidant balance to mitochondrial potential, ATP synthesis, and insulin secretion.

Mitochondrial dysfunction has been postulated to be a key factor in the development of type 2 diabetes. Defective GSIS and reduced β cell mass were seen in patients with mitochondrial dysfunction and in a relevant mouse model (137). A study using mice with dominant-negative IGF-1 receptor mutations in skeletal muscles (32) unveiled two-stage mechanisms for their gradually developed deterioration of mitochondrial functions and insulin resistance-induced β-cell failure. At the first 3 weeks of insulin resistant stage, there were abrogated hyperpolarization of mitochondrial membrane potential, reduced mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, slightly enlarged mitochondria, and attenuated GSIS. At the onset of diabetes (the 10th week), hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia were developed with swollen mitochondria containing disordered cristae, reduced hyper-polarization of mitochondrial potential, impaired Ca2+-signaling, and diminished glucose-stimulated production of ATP/ADP and insulin release. In diabetic islets, expression of 36 mitochondrial proteins, including inner membrane proteins of electron transport chain, was altered (90).

Desired Outcomes of Antioxidant Enzymes

Two lines of existing data or perceived views render upregulating antioxidant defense in islets as a strategic treatment of diabetes or insulin resistance. The first is the predicted susceptibility of β cells to oxidative stress as mentioned above. The second is the responsiveness of key regulators of β cells and insulin, including PDX1, FOXA2, and UCP2 to ROS (12, 61, 63). Indeed, ROS-induced impaired insulin synthesis or secretion in insulin-producing or -secreting cells was partially alleviated by overproduction of GPX1, SOD1, and catalase (88, 131, 141). Enhancing expression of Gpx1 and(or) Sod1 up to twofold protected NIT-1 mouse insulinoma cells from H2O2 and menadione, but only the Gpx1 overexpression increased the cell survival after hypoxia reoxygenation (82). Protection of rat-derived insulin-secreting INS-1 cells against both ROS and RNS resulted from an adenoviral-mediated Gpx1 overexpression (97). While cytoplasmic catalase overexpression in insulin-producing RINm5F cells provided stronger protection against H2O2 toxicity, only mitochondrial overexpression of this enzyme in these cells provided protection against menadione that preferentially generates superoxide radicals in mitochondria (42). The mitochondrial catalase overexpression was also preferentially protective against toxicity of interleukin-1β and a pro-inflammatory cytokine mixture. In another study with the same cell line, overexpression of catalse, Gpx1, and Sod1 conferred protection against toxicity of the cytokine mixture (interleuk-1β, tumor necrosis factor-α, and γ-interferon) but not that of interleuk-1β alone (89).

Adenoviral overexpression of glutathione-related enzymes in pancreatic islets can prevent oxidative stress-induced insulin loss (113). The glucose- or ribose-induced islet peroxide accumulation and the adverse consequences of insulin mRNA, content, and secretion were aggravated by a GSH synthesis inhibitor, but alleviated by increasing islet GPX1 activity (127). After isolate islets were transferred with Sod2 gene by adenoviral infection and transplanted into STZ-treated nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice, these islets functioned 50% longer than the control ones (7). When islets from transgenic mice cooverexpressing human Sod1, Sod3, and/or Gpx1 were exposed to hypoxanthine/xanthine oxidase treatment in vitro, relative resistance was in the following order: [SOD1 + SOD3 + GPX1] > [SOD3 + GPX1] > [SOD3] > WT (99). However, overexpression of all three enzymes in combination was required to display a protection against hypoxia/reoxygenation or an improvement in blood glucose in STZ-treated recipient mice transplanted with the transgenic islet grafts. When islets from mice with β cell-specific overexpression of metallothionein up to 30-fold were exposed to STZ in vitro, they exhibited much less islet disruption, DNA breakage, and depletion of NAD+ (16). Meanwhile, an overexpression of thioredoxin in islets prolonged graft survival in autoimmune diabetic NOD mice (21). This improvement resembled effects of intraperitoneal injections of oleanoic acid on graft-specific immune response.

Studies using diabetic models showed improved insulin sensitivity by antioxidants, including lipoic acid (52). Improved insulin sensitivity was also seen in insulin-resistant and/or diabetic patients by treating them with antioxidant vitamins (28). Further, injections of an analog of antioxidant probucol prevented type 1 diabetes in NOD and multiple low doses–STZ mice models (55). An earlier study (111) showed that SOD (105 mU/g) administered intravenously to rats 50 min before STZ intravenous injection (45 mg/kg) abolished the STZ-induced pancreatic insulin decrease and glucose intolerance. It is clinically relevant that induced expression of Gpx3 was required for the regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma)-mediated antioxidant effects produced by thiazolidinediones, a PPARgamma agonist used to improve insulin sensitivity in treating type 2 diabetes (22). In cultured cells with ROS-induced insulin resistance, six treatments designed to modulate ROS status, including two small molecules and four transgenes of cyto-catalase, mito-catalase, Sod1, and Sod2, ameliorated insulin resistance to various extents. A chronic treatment of leptin-deficient ob/ob obese, insulin-resistant mice with antioxidant manganese (III) tetrakis (4-benzoic acid) porphyrin (MnTBAP) and insulin-sensitizing drug rosiglitazone improved insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis (50).

Table 1 depicts main metabolic impacts or phenotypes associated with overexpressing seven common antioxidant enzymes/proteins. Transgenic mice with β cell-specific overexpression of metallothionein were protected from the STZ-induced hyperglycemia, degranulation, and cell death (16). Global overexpression of Sod1 in mice enhanced their resistance to type 1 diabetes induced by alloxan (71). Global or β cell-specific overexpression of Sod1 in NOD mice enhanced their resistance to alloxan-induced diabetes (70, 71). A similar positive effect of Sod1 overexpression in liver of db/db mice was also shown on hepatic ROS, blood glucose level, and insulin sensitivity (72). When Gpx1 was specifically overexpressed in pancreatic β cells in C57BLKS/J mice, their β cells became resistant to multiple injection of STZ (43). After the transgene was introgressed into the pancreatic β cells of db/db mice, hyperglycemia, β cell volume, and insulin granulation and immune-staining were significantly improved.

Table 1.

Summary of Major Metabolic Impact and Phenotype Resulted from Global or Tissue (β Cell and Liver)-Specific Overexpression and Global Knockout of Seven Common Antioxidant Enzymes/Proteins in Mice

| Gene | Phenotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Transgenic (overexpression) | ||

| Catalase (β-cell specific) | Protection of islet insulin secretion against H2O2 and significantly decreased diabetogenic effect of STZ in vivo; no protection against interleukin-1β toxicity or altering effects of syngeneic and allogenic transplantation on islet insulin content | Xu et al. (141) |

| GPX1 (global) | Development of hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, increased β-cell mass, hypersecretion of insulin, insulin resistance, and obesity | McClung et al. (93), Wang et al. (136) |

| GPX1 (β-cell specific) | Protection against STZ, reversing hyperglycemia in db/db mice, and improving β-cell volume and granulation | Harmon et al. (43) |

| GPX1, SOD1, and SOD3 (global) | Protection of islets against hypoxanthine/xanthine oxidase treatment in vitro in the following order: [SOD1 + SOD3 + GPX1] > [SOD3 + GPX1] > [SOD3] > WT; a protection against hypoxia/reoxygenation and an improvement in blood glucose in STZ-treated recipient mice transplanted with the transgenic islet grafts with overexpression of all three enzymes in combination | Mysore et al. (99) |

| Metallothionein (β-cell specific) | Protection of islets from STZ-induced disruption, DNA breakage, and depletion of NAD+; Protection of mice from the STZ-induced hyperglycemia, and degranulation and cell death of islets | Chen et al. (16) |

| Metallothionein, catalase, and SOD2 (β-cell specific) | Accelerating diabetes after cyclophosphamide treatment and spontaneous diabetes in NOD male mice by overexpression of cytoplasmic catalase and methallothionein; no such effect of SOD2 | Li et al. (83) |

| SOD1 (global) | Protection against type 1 diabetes-induced by alloxan | Kubisch et al. (71) |

| SOD1 (β-cell specific) | Protection against alloxan-induced diabetogenesis | Kubisch et al. (70) |

| SOD1 (liver specific) | Decreasing hepatic ROS and blood glucose level, and improving insulin sensitivity in db/db mice | Kumashiro et al. (72) |

| SOD2 (islets) | Extending islet function for 50% longer than that of the control after isolate islets were transferred with Sod2 gene by adenoviral infection and transplanted into STZ-treated NOD mice | Bertera et al. (7) |

| SOD2 and catalase (β-cell specific) | Protection of islets against STZ and peroxynitrite, but not cytokine toxicity by the co-expression of both enzymes | Chen et al. (17) |

| SOD3 (β-cell specific) | No effect on diabetes onset and incidence in NOD mice | Sandstrom et al. (115) |

| Thioredoxin (islet) | Prolonging islet graft survival in autoimmune diabetic NOD mice | Chou and Sytwu (21) |

| Knockout | ||

| Catalase | Sensitizing the mutant mice to alloxan-induced diabetogenesis, accelerated severe atrophy of pancreatic islets, and apoptosis; but not impact on STZ-induced diabetes | Kikumoto et al. (66) |

| GPX1 | Enhancing mouse resistance to high-fat diet induced insulin resistance | Loh et al. (86) |

| GPX1 | Decreasing pancreatic β-cell mass and plasma insulin concentration, mild pancreatitis | Wang et al. (135) |

| SOD1 | Decreasing pancreatic β-cell mass, plasma insulin concentration, and body weight; mild hyperglycemia; attenuated glucose-stimulated insulin secretion; improved insulin sensitivity; mild pancreatitis | Wang et al. (135) |

| GPX1 + SOD1 | Similar to the phenotypes of Sod1 knockout | Wang et al. (135) |

The list is derived as a representation instead of an exhausted record. Missing of any important models is solely due to authors' limited knowledge and manuscript length.

GPX1, glutathione peroxidase 1; NOD, nonobese diabetic; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SOD1, superoxide dismutase 1; STZ, streptozotocin; WT, wild type.

Using a rat insulin promoter to direct pancreatic β cell-specific overexpression of catalase, Xu and associates (141) produced seven transgenic lines of mice sensitive to Friend leukemia virus B (FBV) with increased catalase activity in islets up to 50-fold. While the overproduced catalase activity had no detrimental effect on islet function, it conferred a remarkable protection of islet insulin secretion against H2O2 and significantly decreased diabetogenesis of STZ in vivo. A recent study using homozygous acatalase mice mutant has demonstrated similarly crucial role of catalase in protecting against alloxan-induced type 1 diabetes (66). Compared with WT controls, the mutant mice had a higher (72 vs. 32%) incidence of diabetes after intraperitoneal injection of 180 mg of alloxan/kg of body weight. This high dose of alloxan also accelerated severer atrophy of pancreatic islets, and induced greater apoptosis in pancreatic β cells in the acatalasemic mice than in the control mice.

Intriguing Metabolic Enigma

Not all transgenes of antioxidant enzymes or proteins confer a metabolic protection against all insults (Table 1). When a 50-fold β cell-specific overproduction of catalase activity in FVB mice clearly protected islet against H2O2 and STZ toxicity, it did not provide any protection against interleukin-1β toxicity or alter effects of syngeneic and allogenic transplantation on islet insulin content (141). It was very intriguing that lack of catalase did not induce any compensation of GPX or SOD activity in pancreas and did not affect mouse susceptibility to STZ (but to alloxan)-induced diabetes (66). Likewise, β cell-specific overexpression of either Sod2 or Sod3 in NOD mice did not affect incidence of spontaneous diabetes (83, 115). When insulin-producing RINm5F cells were stably transfected with the Sod2 gene, their cell viability was not different from the control or cells transfected with antisense of the Sod2 gene after exposure to H2O2 or hypoxanthine/xanthine oxidase (87). However, overexpression of Sod2 in these cells actually rendered them more susceptible to proinflammatory cytokine-induced decreases in viability and proliferation rate. In contrast, suppressing Sod2 expression enabled the cells more resistant to this type of cytokine toxicity. Thus, altering mitochondrial balance between superoxide- and H2O2-scavanging activities may constitute a greater cell vulnerability to cytokines. In addition, islets isolated from transgenic mice with coexpression of Sod2 and catalase in β cells were not more resistant to cytokine toxicity than the controls, despite a clear advantage in coping with STZ and peroxynitrite (17).

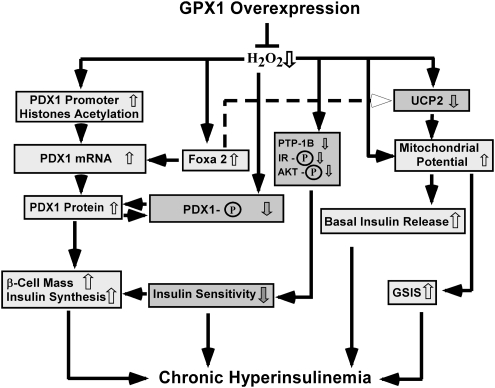

Most striking, two independent studies have shown severe and long-term metabolic disorders associated with antioxidant enzyme transgenes. First, β cell-specific overexpression of cytoplasmic catalase and methallothionein greatly accelerated diabetes after cyclophosphamide treatment and spontaneous diabetes in NOD male mice, despite a protection against the cytokine-induced ROS production by both antioxidant proteins and a decrease in the STZ-induced diabetes in the metallothionein transgenic mice (83). Second, mice OE developed hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance, and obesity at 6 months of age (93). With a 20-fold increase in GPX1 activity, the OE islets were featured by ROS diminishing, but elevated β cell mass, insulin production, and GSIS (136). Diet restriction removed all of these type 2 diabetes phenotypes except for hyperinsulinemia and hypersecretion of insulin (136) (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Scheme of Gpx1 overexpression leading to chronic hyperinsulinemia. ↑, Activation or increase; ↓, inhibition or decrease; ⊥, decrease; P, phosphorylation. AKT, protein kinase B; FOXA2, forkhead box A2; GPX1, glutathione peroxidase 1; GSIS, glucose-stimulated insulin secretion; PDX1, pancreatic duodenal homeobox 1; PTP, protein tyrosine phosphatase; PTP-1B, protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B; UCP2, uncoupling protein 2.

Comparatively, only overexpression of Gpx1 elevated β cell mass, insulin production, and GSIS (136). In contrast, overproducing metallothionein and catalase in β cells actually accelerated the cytokine-induced β cell death (83). Seemingly, the positive effect of GPX1 on β cell mass and insulin production is not shared by other antioxidant proteins. This is because baselines of insulin concentration or insulin gene expression in islets were not altered by overexpressing catalase up to 50-fold (141) (83), metallothionein up to 30-fold (16, 83), or three forms of SOD enzymes up to 10-fold (17, 99). Although infection of rat islets with adenovirus encoding human Gpx1 gene resulted in protections against the ribose-induced loss of insulin mRNA, content, and secretion, baseline levels of these three measures were unaltered (127). The relatively low (sixfold) increase in GPX1 activity in islets might be insufficient to induce significant elevation in baseline insulin synthesis or the 72 h infection of rat islets did not allow an illustration of GPX1 overexpression benefit to β cell mass.

Reciprocally, knockout of Gpx1 enhances body resistance to high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance (86) (Table 1). Although knockouts of Gpx1 and Sod1 each alone or in combination resulted in similar decreases in pancreatic β cell mass and plasma insulin concentration, metabolic pathways for inducing their phenotypes are distinctly different (135). Further, the Sod1 knockout (Sod1−/−) mice developed more typical type 1 diabetes phenotypes than the Gpx1−/− mice. Compared with the WT, the Sod1−/− mice exhibited reduced body weight, hypoinsulinemia, blocked GSIS, hyperglycemia, and enhanced insulin sensitivity, along with elevated blood ketone bodies and urine glucose, pancreatitis, increased bone deterioration (134), and eye problems (44, 104). In comparison, the Gpx1−/− mice developed only moderate hyperglycemia and showed no body weight change over the WT. However, these Gpx1−/− mice were more sensitive to the cerulein-induced increase in serum amylase. Overall, knockout of Sod1 exerted a more potent impact on islet function and pancreatic integrity than that of Gpx1. Outcomes of double knockout of both enzymes resembled those of Sod1 knockout. Just as implicated in the cell case with mitochondrial catalase transfection (87), altering intracellular superoxide tone was probably more detrimental than that of hydroperoxides to insulin function and glucose metabolism. When type 1 diabetes was induced by alloxan in female WT, Sod1−/−, and Sod1 overexpressing mice before pregnancy, blood glucose concentrations and fetuses hepatic isoprostane levels were actually lower on the Sod1−/− mice than in the other two groups (142).

Potential Risk of Human Health

Despite observed or perceived benefits of antioxidant enzymes or nutrients to diabetes (27, 46, 132), a potential risk associated with this notion has emerged (98). Increased erythrocyte GPX1 activity is strongly correlated with insulin resistance in gestational diabetic women (18). Most notably, at least eight major human studies have shown that Se supplements may be hyperglycemic, hyperlipidemic, and pro-diabetic. Adverse blood glucose and lipid profiles were seen in the U.S. and European adults with high plasma Se status (9, 10, 23, 75, 76, 122). Supplementing Se at 200 μg daily for 7.4 years to Se-adequate and initially nondiabetic old males enhanced their type 2 diabetes incidence by 50% (123). In particular, those subjects in the highest tertile of baseline plasma Se level displayed a hazard ratio of 2.7. Partially due to this increased risk potential, the planned 12-year Se and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELCT) was prematurely stopped in October 2008 (85).

Obviously, roles and mechanisms of antioxidant enzymes or nutrients in diabetes are far from clear. Pardoxically, antioxidant supplementation offsets health-promoting benefit of physical exercise in humans (110). Many past studies have overly amplified their transient benefits against a bolus of ROS, but neglected long-term metabolic consequences of shifting cellular redox status. In addition, antioxidant benefits to diabetic patient treatments may not be extrapolated to normal subjects for preventive purposes.

Novel Epigenetic Regulation of PDX1 by Antioxidant Enzymes

Because of the importance of PDX1 in controlling pancreatic β cell differentiation, survival, and insulin synthesis and its responsiveness to ROS, we have explored novel epigenetic regulations of PDX1 for explanation to the β cell and insulin phenotypes in mice with altered GPX1 and SOD1. Hyperinsulinemia and hypertrophy of β cell mass in the Gpx1 overexpressing mice concurred with an elevated levels of H3 and H4 acetylation in the proximal region of promoter in pancreatic islets (136). Meanwhile, islets from these mice were more resistant to H2O2-induced H3 and H4 hypoacetylation and had greater Pdx1 mRNA and protein levels than the WT islets (Fig. 2). In contrast, decreased β cells mass and plasma insulin concentration in mice with single knockout of SOD1 or double knockouts of Gpx1 and Sod1 was coincided with a declined H3 acetylation and H3K4 methylation in the Pdx1 promoter region. Such changes were also correlated to decreases of Pdx1 mRNA and protein (106).

Plasticity of chromatin is well known to be governed by multisubunit protein complexes that regulate chromosomal structure and activity (48). Such complexes include ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling factors that are involved in many fundamental processes, including DNA replication, transcription, and repairing as well as chromosome structure maintenance (48). The proximal region of Pdx1 promoter consists of an islet-specific expression consensus E-box motif, which predominantly binds the upstream transcription factor (117). Site-specific acetylation or deacetylation of nucleosomal histone H3 and H4 is central to the switch between permissive and repressive chromatin structure and thus activation or repression of transcription (24). With a high affinity for upstream transcription factor binding (133), H3 and H4 are the core histones with high levels of acetylation at the active transcriptional loci (128). Preceding transcriptional activation (78), hyperacetylation of H3 and H4 helps remodel the chromatin in the Pdx1 promoter to form more accessible structure for transcription (101). Thus, hyperacetylation of H3 and H4 in the OE islets should help in activating and hypoacetylation of H3 in the Sod1−/− and double knockout of Gpx1 and Sod1 islets in suppressing Pdx1 gene transcription. These distinct epigenetic regulations might partially explain their opposite changes in islet Pdx1 mRNA expression. Lowering intracellular ROS by overproduction of GPX1 activity enhanced H3 and H4 acetylation, which allowed the OE mice to maintain a high level of functional PDX1 protein to promote β cell differentiation and insulin synthesis for compensating insulin resistance in these obese animals, so overt diabetes was avoided (136).

Another possible class of epigenetic regulations of Pdx1 is DNA methylation. This modification takes place at the C5 position of cytosine, and is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (118). The methylation status of CpG islands within promoter sequences serves as an essential regulatory element in modifying the binding affinity of transcription factors to DNA binding sites. While most CpG islands remain unmethylated in normal cells, they may be methylated de novo under some circumstances. Despite unclear impacts of antioxidant enzymes on Pdx1 methylation, relevance of this epigenetic regulation has been well demonstrated. A recent study indicated that Pdx1 was 1 of only 15 CpG genes among 1749 examined ones with CpG islands that were methylation susceptible when methylation was upregulated by overexpression of a DNA methyltransferase (31). Development of type 2 diabetes in rats with intrauterine growth retardation was associated with progressive epigenetic silencing of Pdx1, in which methylation of the CpG island in the proximal promoter led to permanent silence of the Pdx1 locus after the onset of diabetes in adulthood (106). Apparently, it will be fruitful to study how antioxidant enzyme overexpression or knockout out affects methylation of Pdx1 promoter and the subsequent impact on its function.

Regulation of Functional PDX1 Protein by Antioxidant Enzymes

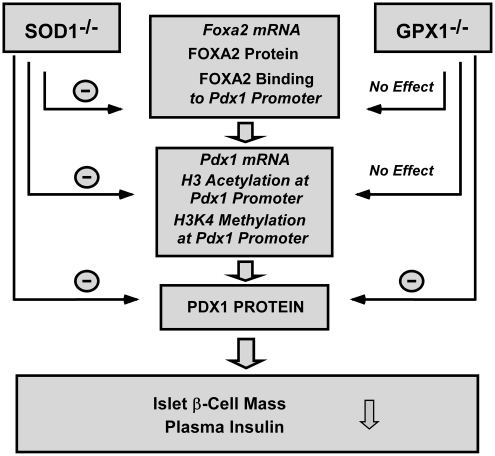

Because PDX1 exerts its function mainly in nucleus, amount of functioning PDX1 protein at a given time depends on its transcription (mRNA), translation (protein), posttranslational modification (phosphorylation), and nucleocytoplasmic translocation of PDX1 (58). As mentioned above, OE mice had elevated levels of Pdx1 mRNA and protein, along with attenuated PDX1 protein phosphorylation (degradation) in pancreatic islets (136) (Fig. 2). As a result, these mice maintained a greater level of functional PDX1 protein than the WT mice to produce hyperinsulinemia and hypertrophy of β cell mass. Supplementing C57BL/KsJ-db/db mice with dietary antioxidant nutrients produced similar positive effects on PDX1 protein (59). However, overexpression of catalase that shares the same substrate of hydrogen peroxide with GPX1 did not give such benefit, but accelerated the cytokine-induced PDX1 protein disappearance (83). Decreased β cell mass and plasma insulin concentration in mice with single and double knockouts of Gpx1 and Sod1 was accompanied by a declined pancreatic PDX1 protein (135) (Table 1 and Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Comparative impacts of Gpx1 and Sod1 knockouts on regulation of pancreatic islet FOXA2, PDX1, and β cell mass and function. ↓, Inhibition; SOD1−/−, superoxide dismutase 1 knockout mice.

Impacts of GPX1 overproduction on islet functional PDX1 protein may be mediated at multiple sites by ROS directly or indirectly through c-jun terminal kinase (JNK), protein kinase B (AKT), and protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B (PTP-1B) (63, 68, 73). Expression and function of these proteins are highly sensitive to ROS (39, 83, 94). Diminishing islet ROS by overproducing GPX1 could improve posttranslational stability of PDX1 protein. This is because hydrogen peroxide induces phosphorylation of PDX1 protein on ser61 and/or ser66 (12), resulting in an increased degradation rate and decreased half-life of the protein. In fact, the ROS-diminished OE islets showed decreased phosphorylated and elevated total PDX1 protein (136) (Fig. 2). Meanwhile, hydrogen peroxide downregulates the DNA binding activity of PDX1 by inducing translocation of this protein from nucleus to cytoplasm (63). Lowering islet ROS should attenuate this event and allow more PDX1 protein to function in nucleus.

Knockout of Sod1 elevated islet superoxide levels and decreased Pdx1 mRNA and protein, contrary to the change in the OE mice (135). This implies a similar role of hydroperoxides and superoxide in regulating functional PDX1 protein. However, knockout of Gpx1 actually elevated islet ROS (not superoxide) levels, but exerted no impact on Pdx1 mRNA. Thus, either the induced changes in islet ROS were insufficient to affect Pdx1 gene transcription, or the PDX1 protein decrease in the Gpx1−/− was mainly attributed to accelerated protein phosphorylation (degradation) by the elevated H2O2 (12).

The attenuated ROS status in the OE mice decreased JNK activation (136). Inhibiting the JNK pathway protects β cells from glucose toxicity (60) and the oxidative stress induced-nuclear localization of forkhead transcription factor FOXO1 (64). FOXO1 was found to compete with FOXA2 for binding sites in the Pdx1 promoter and thus suppressed Pdx1 gene transcription in pancreatic β cells (68). Therefore, the overproduced GPX1 activity might enhance Pdx1 transcription by repressing the JNK-FOXO1 pathway. In addition, suppression of phosphorylation of JNK also inhibits the ROS-induced nucleo-cytoplasmic translocation of PDX1 (63, 64).While the decreased AKT phosphorylation at Thr308 in the OE islets might attenuate the H2O2-mediated phosphorylation (degradation) of PDX1 protein (12), it could decrease phosphorylation of Foxo1 and then downregulates Pdx1 transcription by the above-discussed mechanism (67, 68). The decrease of PTP-1B protein in the OE islets resembled the phenotype of PTP1-1B knockout mice (73). The improvement associated with β cell-specific overproduction of GPX1 in db/db mice was mediated by a reversed loss of v-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene family protein A (MafA), which is another important transcriptional factor like PDX1 for β cells and insulin expression (43).

Superoxide-Dependent Regulation of Foxa2 by SOD1

As a key activator of Pdx1 transcription, FOXA2 binds the promoter/enhancer of the Pdx1 gene (139) and activates Pdx1 gene expression in vivo (77). Because the Sod1 promoter contains four binding sites for FOXA2 (105), and the mouse Sod1 is indeed a transcriptional target of Foxa1 (14), illustrating a reciprocal effect of Sod1 knockout on FOXA2 expression and function (Fig. 3) reveals a novel interdependence or positive feedback mechanism between these two proteins. The Sod1 knockout caused an elevation of islet superoxide tone and resulted in substantial decreases in islet FOXA2 mRNA, protein, and binding to the Pdx1 promoter (135). A direct link between the FOXA2 response and the SOD1 function was verified by treating WT and Sod1−/− islets with the SOD1 enzyme inhibitor and mimic, respectively (135). Such a change was correlated to decreases of Pdx1 mRNA and protein (106). In contrast, knockout of Gpx1 elevated islet ROS but not superoxide levels, which exerted no impact on FOXA2 mRNA, protein, and its binding to the Pdx1 promoter (135) (Fig. 3). Thus, effects of Sod1 knockout on FOXA2 expression and binding function were superoxide dependent. Because of the distinct differences in regulating FOXA2 expression and function between the two H2O2- and superoxide-scavenging enzymes (Fig. 3), adequate consideration should be given to metabolic subtlety of different forms of ROS in β cells and insulin function.

Regulation of UCP2 by Antioxidant Enzymes

Elevated GSIS in the OE mice might be explained by elevated islet mitochondrial potential and decreased UCP2 protein (136) (Fig. 2). Meanwhile, attenuated GSIS in the Sod1−/− and Gpx1−/− mice was consistent with decreases in islet ATP content and increases in UCP2 protein (135). Because UCP2 may be activated by endogenously produced superoxide (69) and can modulate mitochondrial generation of H2O2 (100), opposite responses of UCP2 induced by overexpression and knockout of Gpx1 and(or) Sod1 may be interpreted as a metabolic compensation. A normal level of ROS in mitochondria is required for GSIS (79). Although a direct link of GPX1 function to islet UCP2 level was demonstrated by treating WT islets with a GPX1 mimic, ebselen (136), the sole UCP2 change may not fully explain a virtually blocked GSIS in Sod1−/− but not Gpx1−/− mice. A concurrent downregulation of other important regulators of GSIS (GLUT2, KIR6.2, and GLPR1) in the Sod1−/− may offer additional explanations. Their alterations have been seen in insulin secretion disorders (4, 41, 119, 129).

Regulation of Insulin Signaling and Sensitivity by Antioxidant Enzymes

Because ROS has been shown to affect various steps of insulin signaling cascade starting from insulin receptor phosphorylation (45), impacts of antioxidant enzymes on body insulin sensitivity can be explained at least partially by their ability to modulate intracellular ROS status. The GPX1 overproduction-induced insulin resistance was associated with an attenuated phosphorylation of insulin receptor (β subunit) and AKT (Ser473 and Thr308) in liver and muscle (93) (Fig. 2). Earlier, a pro-insulin or insulin-mimic action of H2O2 on phosphorylation of β subunit of insulin receptor was shown in rat adipocytes (45). The action was not a direct effect of hydrogen peroxide on the receptor, but mediated through downregulation PTP-1B, a negative regulator of insulin signaling the cellular machinery (45). Because the overproduced GPX1 activity diminished islet ROS, oxidative inhibition of PTPs including PTP-1B by H2O2 was presumably lifted. Knockout of Ptp-1b increased phosphorylation of insulin receptor in liver and muscle, and enhanced body resistance to high-fat diet-induced weight gain and insulin resistance (25). Similar enhancements in the Gpx1−/− mice were correlated with increased oxidation of the PTP family member phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase–phosphatase with tensin homology in muscle that terminates signals generated by phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (86). An enhanced AKT signaling in muscle of these mice also helped promote glucose uptake. Both improvements were reversed by antioxidant N-acetylcysteine. While increased phosphorylation of AKT and insulin receptor in the Sod1−/− mice might additively help improve insulin sensitivity, upregulation of only AKT phosphorylation in the Gpx1−/− mice did not produce a significant effect on this function.

Being highly responsive to oxidative stress, JNK is phosphorylated in diabetic conditions, leading to inhibition of insulin gene expression (58). Activation of JNK increased phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) on Ser307 that disrupted the interaction between the catalytic domain of the insulin receptor and the phosphotyrosine binding domain of IRS-1 (1, 2). Thus, ablation of Jnk increased mouse insulin sensitivity (47). Because downregulation of JNK in the OE mice did not result in improved insulin sensitivity (136), the insulin resistance-inducing factors in OE mice might be too strong to offset. Meanwhile, positive effects of Sod1 overexpression in liver of db/db mice were attributed to decreased expression of phosphoenol-pyruvate carboxykinase and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1α, two main regulators of gluconeogenic genes (72). Improved insulin sensitivity in these transgenic mice over their controls was mediated in part by attenuating phosphorylation of cAMP-responsive element-binding protein and JNK.

Closing Remarks

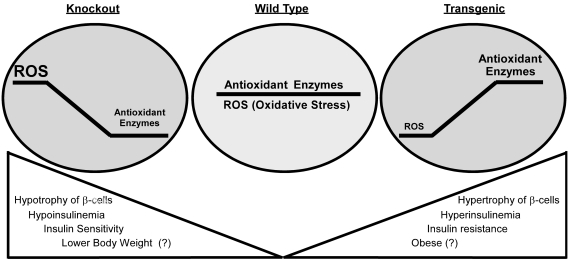

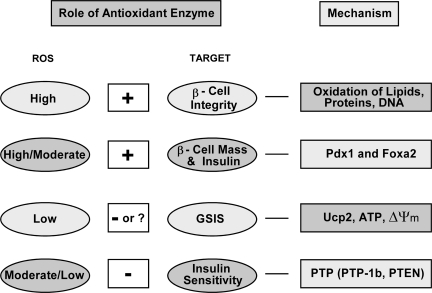

Although OE and knockouts of Gpx1 and/or Sod1 produced nearly symmetric β cell and insulin phenotypes (Fig. 4), physiological roles of antioxidant enzymes in β cells and diabetes are undoubtedly complex. Actual outcome of altering a given enzyme depends on body or tissue ROS status and selected function target (Fig. 5). When ROS is high, such as in overt diabetes, antioxidant enzymes protect β cells against hyperglycemia-induced oxidative destructions of macromolecules. These enzymes also help prevent oxidative inhibitions of key transcriptional factors like PDX1 and thus maintain β cell mass and function. However, overly diminishing intracellular ROS by excessively high antioxidant enzyme activities dys-regulates GSIS or insulin signaling. Overall, we should not overlook metabolic difference or subtlety between overexpression and knockout of a given antioxidant enzyme, mitochondrial and cytosolic locations, hydroperoxide and superoxide scavenging functions, and pro-oxidants- and cytokines-induced ROS. Apparently, acute effects of antioxidant enzymes on bolus of ROS may be different from their chronic effects on metabolically generated endogenous ROS. A good example is the above-discussed lack of protection of antioxidant enzyme overexpression against cytokine toxicity in β cells or islets. Likewise, a transient benefit may even evolve into a metabolic disorder in a long run. Experimentally, the OE mice may be used as a new model to study role of antioxidant enzymes in insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and obesity. Meanwhile, the Sod1−/− mice may offer a novel model to study antioxidant enzymes in type 1 diabetes and pancreatitis (Fig. 3). Technically, animal models with tissue specific knockouts or tissue-specific overexpression (in addition to β cell-specific) of antioxidant enzymes should be generated to fully elucidate specific mechanisms for their metabolic roles in β cells and diabetes.

FIG. 4.

Symmetric phenotypes of pancreatic islet β cells and body insulin produced by overexpression of Gpx1 and knockout of Gpx1 and Sod1 each alone or together. The three inside circles represent different status of oxidants/antioxidants: balanced in wild type; reductive stress in the transgenic model; oxidative stress in the knockout models.

FIG. 5.

Metabolic role, physiological importance, and molecular mechanism of antioxidant enzymes for different target functions under various ROS status. +, Protection or positive role; −, negative role; ?, questionable role. PTEN, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase–phosphatase with tensin homology.

Abbreviations Used

- AKT

protein kinase B

- FOXA1

forkhead box A1

- FOXA2

forkhead box A2

- FOXO1

forkhead box O1

- GPX1

glutathione peroxidase 1

- Gpx1−/−

glutathione peroxidase knockout mice

- GSIS

glucose-stimulated insulin secretion

- IR

insulin receptor

- IRS-1

insulin receptor substrate-1

- JNK

c-jun terminal kinase

- NOD

nonobese diabetic

- OE

overexpressing GPX1

- PDX1

pancreatic duodenal homeobox 1

- PTEN

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase–phosphatase

with tensin homology

- PTP

protein tyrosine phosphatase

- PTP-1B

protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B

- RNS

reactive nitrogen species

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SOD1

superoxide dismutase 1

- Sod1−/−

superoxide dismutase 1 knockout mice

- STZ

streptozotocin

- UCP2

uncoupling protein 2

- WT

wild type

Acknowledgment

Research in the authors' laboratory was supported in part by DK53018 (XGL).

References

- 1.Aguirre V. Uchida T. Yenush L. Davis R. White MF. The c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase promotes insulin resistance during association with insulin receptor substrate-1 and phosphorylation of Ser307. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9047–9054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.9047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguirre V. Werner ED. Giraud J. Lee YH. Shoelson SE. White MF. Phosphorylation of Ser307 in insulin receptor substrate-1 blocks interactions with the insulin receptor and inhibits insulin action. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:1531–1537. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101521200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahlgren U. Jonsson J. Jonsson L. Simu K. Edlund H. Beta cell-specific inactivation of the mouse Ipf1/Pdx1 gene results in loss of the beta-cell phenotype and maturity onset diabetes. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1763–1768. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.12.1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahren B. Islet G protein-coupled receptors as potential targets for treatment of type 2 diabetes. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:369–385. doi: 10.1038/nrd2782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Archuleta TL. Lemieux AM. Saengsirisuwan V. Teachey MK. Lindborg KA. Kim JS. Henriksen EJ. Oxidant stress-induced loss of IRS-1 and IRS-2 proteins in rat skeletal muscle: role of p38 MAPK. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:1486–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asayama K. Kooy N. Burr I. Effect of vitamin E deficiency and selenium deficiency on insulin secretory reserve and free radical scavenging systems in islets: decrease of islet manganosuperoxide dismutase. J Lab Clin Med. 1986;107:459–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertera S. Crawford ML. Alexander AM. Papworth GD. Watkins SC. Robbins PD. Trucco M. Gene transfer of manganese superoxide dismutase extends islet graft function in a mouse model of autoimmune diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52:387–393. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blair AS. Hajduch E. Litherland GJ. Hundal HS. Regulation of glucose transport and glycogen synthesis in l6 muscle cells during oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36293–36299. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bleys J. Navas-Acien A. Guallar E. Selenium and diabetes: more bad news for supplements. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:271–272. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-4-200708210-00177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bleys J. Navas-Acien A. Stranges S. Menke A. Miller ER III. Guallar E. Serum selenium and serum lipids in US adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:416–423. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.2.416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bochkis IM. Rubins NE. White P. Furth EE. Friedman JR. Kaestner KH. Hepatocyte-specific ablation of Foxa2 alters bile acid homeostasis and results in endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nat Med. 2008;14:828–836. doi: 10.1038/nm.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boucher M-J. Selander L. Carlsson L. Edlund H. Phosphorylation marks IPF1/PDX1 protein for degradation by glycogen synthase kinase 3-dependent mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:6395–6403. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butler AE. Janson J. Soeller WC. Butler PC. Increased beta-cell apoptosis prevents adaptive increase in beta-cell mass in mouse model of type 2 diabetes: evidence for role of islet amyloid formation rather than direct action of amyloid. Diabetes. 2003;52:2304–2314. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.9.2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carroll JS. Liu XS. Brodsky AS. Li W. Meyer CA. Szary AJ. Eeckhoute J. Shao W. Hestermann EV. Geistlinger TR. Fox EA. Silver PA. Brown M. Chromosome-wide mapping of estrogen receptor binding reveals long-range regulation requiring the forkhead protein FoxA1. Cell. 2005;122:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ceriello A. Oxidative stress and glycemic regulation. Metabolism. 2000;49:27–29. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(00)80082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen H. Carlson EC. Pellet L. Moritz JT. Epstein PN. Overexpression of metallothionein in pancreatic beta-cells reduces streptozotocin-induced DNA damage and diabetes. Diabetes. 2001;50:2040–2046. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.9.2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen H. Li X. Epstein PN. MnSOD and catalase transgenes demonstrate that protection of islets from oxidative stress does not alter cytokine toxicity. Diabetes. 2005;54:1437–1446. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.5.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen X. Scholl TO. Leskiw MJ. Donaldson MR. Stein TP. Association of glutathione peroxidase activity with insulin resistance and dietary fat intake during normal pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5963–5968. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng W-H. Ho Y-S. Ross DA. Han Y. Combs GF., Jr Lei XG. Overexpression of cellular glutathione peroxidase does not affect expression of plasma glutathione peroxidase or phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase in mice offered diets adequate or deficient in selenium. J Nutr. 1997;127:675–680. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.5.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng W-H. Ho Y-S. Valentine BA. Ross DA. Combs GF., Jr Lei XG. Cellular glutathione peroxidase is the mediator of body selenium to protect against paraquat lethality in transgenic mice. J Nutr. 1998;128:1070–1076. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.7.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chou FC. Sytwu HK. Overexpression of thioredoxin in islets transduced by a lentiviral vector prolongs graft survival in autoimmune diabetic NOD mice. J Biomed Sci. 2009;16:71. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-16-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chung SS. Kim M. Youn B-S. Lee NS. Park JW. Lee IK. Lee YS. Kim JB. Cho YM. Lee HK. Park KS. Glutathione peroxidase 3 mediates the antioxidant effect of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma in human skeletal muscle cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:20–30. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00544-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Czernichow S. Couthouis A. Bertrais S. Vergnaud A-C. Dauchet L. Galan P. Hercberg S. Antioxidant supplementation does not affect fasting plasma glucose in the supplementation with antioxidant vitamins and minerals (SU.VI.MAX) study in France: association with dietary intake and plasma concentrations. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:395–399. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eberharter A. Becker P. Histone acetylation: a switch between repressive and permissive chromatin. Second in review series on chromatin dynamics. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:224–229. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elchebly M. Payette P. Michaliszyn E. Cromlish W. Collins S. Loy AL. Normandin D. Cheng A. Himms-Hagen J. Chan C-C. Ramachandran C. Gresser MJ. Tremblay ML. Kennedy BP. Increased insulin sensitivity and obesity resistance in mice lacking the protein tyrosine phosphatase-1b gene. Science. 1999;283:1544–1548. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5407.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Esposito LA. Kokoszka JE. Waymire KG. Cottrell B. MacGregor GR. Wallace DC. Mitochondrial oxidative stress in mice lacking the glutathione peroxidase-1 gene. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28:754–766. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00161-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evans J. Goldfine I. Alpha-lipoic acid: a multifunctional antioxidant that improves insulin sensitivity in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2000;2:401–413. doi: 10.1089/15209150050194279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Evans JL. Goldfine ID. Maddux BA. Grodsky GM. Are oxidative stress-activated signaling pathways mediators of insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction? Diabetes. 2003;52:1–8. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feanny MA. Fagan SP. Ballian N. Liu S-H. Li Z. Wang X. Fisher W. Brunicardi FC. Belaguli NS. PDX-1 expression is associated with islet proliferation in vitro and in vivo. J Surgic Res. 2008;144:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Federici M. Hribal M. Perego L. Ranalli M. Caradonna Z. Perego C. Usellini L. Nano R. Bonini P. Bertuzzi F. Marlier LNJL. Davalli AM. Carandente O. Pontiroli AE. Melino G. Marchetti P. Lauro R. Sesti G. Folli F. High glucose causes apoptosis in cultured human pancreatic islets of langerhans: a potential role for regulation of specific bcl family genes toward an apoptotic cell death program. Diabetes. 2001;50:1290–1301. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.6.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feltus F. Lee E. Costello J. Plass C. Vertino PM. Predicting aberrant CpG island methylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:12253–12258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2037852100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fernandez AM. Kim JK. Yakar S. Dupont JL. Hernandez-Sanchez C. Castle AL. Filmore J. Shulman GI. Le Roith D. Functional inactivation of the IGF-I and insulin receptors in skeletal muscle causes type 2 diabetes. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1926–1934. doi: 10.1101/gad.908001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flekac M. Skrha J. Hilgertova J. Lacinova Z. Jarolimkova M. Gene polymorphisms of superoxide dismutases and catalase in diabetes mellitus. BMC Med Genet. 2008;9:30–35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-9-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fu Y. Cheng W-H. Porres JM. Ross DA. Lei XG. Knockout of cellular glutathione peroxidase gene renders mice susceptible to diquat-induced oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27:605–611. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Furukawa S. Fujita T. Shimabukuro M. Iwaki M. Yamada Y. Nakajima Y. Nakayama O. Makishima M. Matsuda M. Shimomura I. Increased oxidative stress in obesity and its impact on metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1752–1761. doi: 10.1172/JCI21625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao N. LeLay J. Vatamaniuk MZ. Rieck S. Friedman JR. Kaestner KH. Dynamic regulation of Pdx1 enhancers by Foxa1 and Foxa2 is essential for pancreas development. Genes Dev. 2008;15:3435–3448. doi: 10.1101/gad.1752608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gao N. White P. Doliba N. Golson ML. Matschinsky FM. Kaestner KH. Foxa2 controls vesicle docking and insulin secretion in mature beta-cells. Cell Metab. 2007;6:267–279. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gimeno R. Dembski M. Weng X. Deng N. Shyjan A. Gimeno C. Iris F. Ellis S. Woolf E. Tartaglia L. Cloning and characterization of an uncoupling protein homolog: a potential molecular mediator of human thermogenesis. Diabetes. 1997;46:900–906. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.5.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goldstein BJ. Mahadev K. Wu X. Redox paradox: insulin action is facilitated by insulin-stimulated reactive oxygen species with multiple potential signaling targets. Diabetes. 2005;54:311–321. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.2.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grankvist K. Marklund S. Täljedal I. CuZn-superoxide dismutase, Mn-superoxide dismutase, catalase and glutathione peroxidase in pancreatic islets and other tissues in the mouse. Biochem J. 1981;199:393–398. doi: 10.1042/bj1990393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gupta RK. Vatamaniuk MZ. Lee CS. Flaschen RC. Fulmer JT. Matschinsky FM. Duncan SA. Kaestner KH. The MODY1 gene HNF-4α regulates selected genes involved in insulin secretion. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1006–1015. doi: 10.1172/JCI200522365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gurgul E. Lortz S. Tiedge M. Jorns A. Lenzen S. Mitochondrial catalase overexpression protects insulin-producing cells against toxicity of reactive oxygen species and proinflammatory cytokines. Diabetes. 2004;53:2271–2280. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.9.2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harmon JS. Bogdani M. Parazzoli SD. Mak SSM. Oseid EA. Berghmans M. LeBoeuf RC. Robertson RP. Beta-cell-specific overexpression of glutathione peroxidase preserves intranuclear mafa and reverses diabetes in db/db mice. Endocrinology. 2009;150:4855–4862. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hashizume K. Hirasawa M. Imamura Y. Noda S. Shimizu T. Shinoda K. Kurihara T. Noda K. Ozawa Y. Ishida S. Miyake Y. Shirasawa T. Tsubota K. Retinal dysfunction and progressive retinal cell death in SOD1-deficient mice. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1325–1331. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hayes G. Lockwood D. Role of insulin receptor phosphorylation in the insulinomimetic effects of hydrogen peroxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:8115–8119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.22.8115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hirashima O. Kawano H. Motoyama T. Hirai N. Ohgushi M. Kugiyama K. Ogawa H. Yasue H. Improvement of endothelial function and insulin sensitivity with vitamin C in patients with coronary spastic angina: possible role of reactive oxygen species. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1860–1866. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00616-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hirosumi J. Tuncman G. Chang L. Gorgun CZ. Uysal KT. Maeda K. Karin M. Hotamisligil GS. A central role for JNK in obesity and insulin resistance. Nature. 2002;420:333–336. doi: 10.1038/nature01137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hogan C. Varga-Weisz P. The regulation of ATP-dependent nucleosome remodelling factors. Mut Res Fundam Mol Mech Mutagen. 2007;618:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holland AM. Gonez LJ. Naselli G. MacDonald RJ. Harrison LC. Conditional expression demonstrates the role of the homeodomain transcription factor pdx1 in maintenance and regeneration of beta-cells in the adult pancreas. Diabetes. 2005;54:2586–2595. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.9.2586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Houstis N. Rosen ED. Lander ES. Reactive oxygen species have a causal role in multiple forms of insulin resistance. Nature. 2006;440:944–948. doi: 10.1038/nature04634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hui H. Perfetti R. Pancreas duodenum homeobox-1 regulates pancreas development during embryogenesis and islet cell function in adulthood. Eur J Endocrinol. 2002;146:129–141. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1460129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jacob S. Ruus P. Hermann R. Tritschler HJ. Maerker E. Renn W. Augustin HJ. Dietze GJ. Rett K. Oral administration of rac-α-lipoic acid modulates insulin sensitivity in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus: a placebo-controlled pilot trial. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27:309–314. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00089-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Johnson J. Bernal-Mizrachi E. Alejandro E. Han Z. Kalynyak T. Li H. Beith J. Gross J. Warnock G. Townsend R. Permutt M. Polonsky KS. Insulin protects islets from apoptosis via Pdx1 and specific changes in the human islet proteome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:19575–19580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604208103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johnson JD. Ahmed NT. Luciani DS. Han Z. Tran H. Fujita J. Misler S. Edlund H. Polonsky KS. Increased islet apoptosis in Pdx1+/- mice. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1147–1160. doi: 10.1172/JCI16537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnson M. Heineke E. Rhinehart B. Sheetz M. Barnhart R. Robinson K. MDL 29311. Antioxidant with marked lipid- and glucose-lowering activity in diabetic rats and mice. Diabetes. 1993;42:1179–1186. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.8.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jonsson J. Carlsson L. Edlund T. Edlund H. Insulin-promoter-factor 1 is required for pancreas development in mice. Nature. 1994;371:606–609. doi: 10.1038/371606a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kaestner KH. Knochel W. Martinez DE. Unified nomenclature for the winged helix/forkhead transcription factors. Genes Dev. 2000;14:142–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kajimoto Y. Kaneto H. Role of oxidative stress in pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1011:168–176. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-41088-2_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaneto H. Kajimoto Y. Miyagawa J. Matsuoka T. Fujitani Y. Umayahara Y. Hanafusa T. Matsuzawa Y. Yamasaki Y. Hori M. Beneficial effects of antioxidants in diabetes: possible protection of pancreatic beta-cells against glucose toxicity. Diabetes. 1999;48:2398–2406. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.12.2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kaneto H. Kawamori D. Nakatani Y. Gorogawa S. Matsuoka TA. Oxidative stress and the JNK pathway as a potential therapeutic target for diabetes. Drug News Perspect. 2004;17:447–453. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2004.17.7.863704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kaneto H. Miyatsuka T. Kawamori D. Yamamoto K. Kato K. Shiraiwa T. Katakami N. Yamasaki Y. Matsuhisa M. Matsuoka T. PDX-1 and MafA play a crucial role in pancreatic beta-cell differentiation and maintenance of mature beta-cell function. Endocr J. 2008;55:235–252. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k07e-041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Katsuki A. Sumida Y. Urakawa H. Gabazza EC. Murashima S. Nakatani K. Yano Y. Adachi Y. Increased oxidative stress is associated with serum levels of triglyceride, insulin resistance, and hyperinsulinemia in japanese metabolically obese, normal-weight men. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:631–632. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kawamori D. Kajimoto Y. Kaneto H. Umayahara Y. Fujitani Y. Miyatsuka T. Watada H. Leibiger IB. Yamasaki Y. Hori M. Oxidative stress induces nucleo-cytoplasmic translocation of pancreatic transcription factor Pdx-1 through activation of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase. Diabetes. 2003;52:2896–2904. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.12.2896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kawamori D. Kaneto H. Nakatani Y. Matsuoka TA. Matsuhisa M. Hori M. Yamasaki Y. The forkhead transcription factor foxo1 bridges the jnk pathway and the transcription factor pdx-1 through its intracellular translocation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1091–1098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508510200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Keller DM. McWeeney S. Arsenlis A. Drouin J. Wright CVE. Wang H. Wollheim CB. White P. Kaestner KH. Goodman RH. Characterization of pancreatic transcription factor pdx-1 binding sites using promoter microarray and serial analysis of chromatin occupancy. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:32084–32092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700899200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kikumoto Y. Sugiyama H. Inoue T. Morinaga H. Takiue K. Kitagawa M. Fukuoka N. Saeki M. Maeshima Y. Wang D-H. Ogino K. Masuoka N. Makino H. Sensitization to alloxan-induced diabetes and pancreatic cell apoptosis in acatalasemic mice. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2010;1802:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kitamura T. Ido Kitamura Y. Proteins in pancreatic beta cells. Endocr J. 2007;54:507–515. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.kr-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kitamura T. Nakae J. Kitamura Y. Kido Y. Biggs WH., 3rd Wright CV. White MF. Arden KC. Accili D. The forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 links insulin signaling to Pdx1 regulation of pancreatic beta-cell growth. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1839–1847. doi: 10.1172/JCI200216857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Krauss S. Zhang C-Y. Scorrano L. Dalgaard LT. St-Pierre J. Grey ST. Lowell BB. Superoxide-mediated activation of uncoupling protein 2 causes pancreatic beta cell dysfunction. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1831–1842. doi: 10.1172/JCI19774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kubisch H. Wang J. Bray T. Phillips J. Targeted overexpression of Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase protects pancreatic beta-cells against oxidative stress. Diabetes. 1997;46:1563–1566. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.46.10.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kubisch H. Wang J. Luche R. Carlson E. Bray T. Epstein C. Phillips J. Transgenic copper/zinc superoxide dismutase modulates susceptibility to type I diabetes. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9956–9959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kumashiro N. Tamura Y. Uchida T. Ogihara T. Fujitani Y. Hirose T. Mochizuki H. Kawamori R. Watada H. Impact of oxidative stress and peroxisome proliferator- activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 alpha in hepatic insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2008;57:2083–2091. doi: 10.2337/db08-0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kushner JA. Haj FG. Klaman LD. Dow MA. Kahn BB. Neel BG. White MF. Islet-sparing effects of protein tyrosine phosphatase-1b deficiency delays onset of diabetes in irs2 knockout mice. Diabetes. 2004;53:61–66. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kuzuya M. Ando F. Iguchi A. Shimokata H. Glutathione peroxidase 1 Pro198Leu variant contributes to the metabolic syndrome in men in a large Japanese cohort. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:1939–1944. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.6.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Laclaustra M. Navas-Acien A. Stranges S. Ordovas JM. Guallar E. Serum selenium concentrations and hypertension in the us population. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:369–376. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.831552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Laclaustra M. Stranges S. Navas-Acien A. Ordovas JM. Guallar E. Serum selenium and serum lipids in US adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003–2004. Atherosclerosis. 2010;210:643–648. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lee CS. Sund NJ. Vatamaniuk MZ. Matschinsky FM. Stoffers DA. Kaestner KH. Foxa2 controls pdx1 gene expression in pancreatic beta cells in vivo. Diabetes. 2002;51:2546–2551. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.8.2546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lee DY. Hayes JJ. Pruss D. Wolffe AP. A positive role for histone acetylation in transcription factor access to nucleosomal DNA. Cell. 1993;72:73–84. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90051-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Leloup C. Tourrel-Cuzin CC. Magnan C. Karaca M. Castel J. Carneiro L. Colombani A-L. Ktorza A. Casteilla L. Pénicaud L. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species are obligatory signals for glucose-induced insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2009;58:673–681. doi: 10.2337/db07-1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lenzen S. Drinkgern J. Tiedge M. Low antioxidant enzyme gene expression in pancreatic islets compared with various other mouse tissues. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;20:463–466. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(96)02051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Leonard J. Peers B. Johnson T. Ferreri K. Lee S. Montminy MR. Characterization of somatostatin transactivating factor-1, a novel homeobox factor that stimulates somatostatin expression in pancreatic islet cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1993;7:1275–1283. doi: 10.1210/mend.7.10.7505393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lepore DA. Shinkel TA. Fisicaro N. Mysore TB. Johnson LEA. d'Apice AJF. Cowan PJ. Enhanced expression of glutathione peroxidase protects islet β cells from hypoxia-reoxygenation. Xenotransplantation. 2004;11:53–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2004.00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li X. Chen H. Epstein PN. Metallothionein and catalase sensitize to diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice: reactive oxygen species may have a protective role in pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes. 2006;55:1592–1604. doi: 10.2337/db05-1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Like A. Rossini A. Streptozotocin-induced pancreatic insulitis: new model of diabetes mellitus. Science. 1976;193:415–417. doi: 10.1126/science.180605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lippman SM. Klein EA. Goodman PJ. Lucia MS. Thompson IM. Ford LG. Parnes HL. Minasian LM. Gaziano JM. Hartline JA. Parsons JK. Bearden JD., III Crawford ED. Goodman GE. Claudio J. Winquist E. Cook ED. Karp DD. Walther P. Lieber MM. Kristal AR. Darke AK. Arnold KB. Ganz PA. Santella RM. Albanes D. Taylor PR. Probstfield JL. Jagpal TJ. Crowley JJ. Meyskens FL., Jr Baker LH. Coltman CA., Jr Effect of selenium and vitamin E on risk of prostate cancer and other cancers: the selenium and vitamin e cancer prevention trial (SELECT) JAMA. 2009;301:39–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Loh K. Deng H. Fukushima A. Cai X. Boivin B. Galic S. Bruce C. Shields BJ. Skiba B. Ooms LM. Stepto N. Wu B. Mitchell CA. Tonks NK. Watt MJ. Febbraio MA. Crack PJ. Andrikopoulos S. Tiganis T. Reactive oxygen species enhance insulin sensitivity. Cell Metab. 2009;10:260–272. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lortz S. Gurgul-Convey E. Lenzen S. Tiedge M. Importance of mitochondrial superoxide dismutase expression in insulin-producing cells for the toxicity of reactive oxygen species and proinflammatory cytokines. Diabetologia. 2005;48:1541–1548. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1822-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lortz S. Tiedge M. Sequential inactivation of reactive oxygen species by combined overexpression of SOD isoforms and catalase in insulin-producing cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34:683–688. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01371-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lortz S. Tiedge M. Nachtwey T. Karlsen AE. Nerup J. Lenzen S. Protection of insulin-producing RINm5F cells against cytokine-mediated toxicity through overexpression of antioxidant enzymes. Diabetes. 2000;49:1123–1130. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.7.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]