Abstract

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC) have been shown to have immunosuppressive effects in vitro. To test the hypothesis that these effects can be harnessed to prevent graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and graft rejection after hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), we administered a combination of three different immortalized marrow-derived MSC lines (15–30×106 MSC/kg/day, 2–5 times/week) or third-party primary MSC (1.0×106 MSC/kg/day, 3 times/week) to canine recipients (n=15) of dog-leukocyte antigen-haploidentical marrow grafts prepared with 9.2 Gy total body irradiation. Additional pharmacological immunosuppression was not given after HCT. Prior to their in vivo use, the MSC products were shown to suppress alloantigen-induced T cell proliferation in a dose-dependent, major histocompatibility complex-unrestricted and cell contact-independent fashion in vitro. Among 14 dogs evaluable, 7 (50%) rejected their grafts and 7 engrafted with ensuing rapidly fatal acute GVHD (50%). These observations were not statistically different from outcomes obtained with historical controls (n=11) not given MSC infusions (p=0.69). Hence, survival curves for MSC-treated dogs and controls were virtually superimposable (median survival, 18 vs. 15 days, respectively). Finally, outcomes of dogs given primary MSC (n=3) did not appear to be different from those given clonal MSC (n=12). In conclusion, our data fail to demonstrate MSC-mediated protection against GVHD and allograft rejection in this model.

Keywords: Hematopoietic cell transplantation, mesenchymal stromal cells, MSC, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), rejection, canine model

INTRODUCTION

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC) suppress proliferation of alloantigen-activated lymphocytes in vitro in a dose-dependent, cell contact-independent and major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-unrestricted fashion [1–4]. Motivated by the immunosuppressive properties observed in vitro, MSC derived from bone marrow have been evaluated in animal models and in human patients for treatment and prevention of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and allograft rejection [4–12]. Thus far most of the evidence documenting the in vivo immunosuppressive effects of MSC is based on case reports, small case series and phase II studies. [13] While results have not been overwhelmingly positive, no acute or long-term adverse events, including ectopic tissue formation, after MSC infusion have been reported [14–18].

One obstacle that may limit the effectiveness of MSC in vivo is the relatively low numbers of MSC that can be generated for clinical applications. In a recent phase II study of MSC for treatment of steroid-resistant, severe, acute GVHD, 55 patients were treated with allogeneic MSC at a median dose of 1.4 (range, 0.4–9) × 106 cells per infusion [17]. Eighty-nine percent of patients in this study received a total of only one or two MSC infusions. Even though survival of patients who responded to MSC in this study seemed higher (52% at 2 years) than previously described for patients with a similar severity of acute GVHD, randomized controlled trials unequivocally proving the usefulness of MSC for GVHD prevention or treatment have yet to be published. One recently completed phase III study of MSC for treatment of steroid-refractory acute GVHD has thus far only been presented in abstract form and showed no benefit of this intervention with respect to the prospectively defined primary endpoint of a durable complete response for ≥ 28 days [19]. A subgroup analysis, however, suggested a possible therapeutic benefit for patients with liver and gut involvement.

The effectiveness of treating or preventing GVHD by infusing MSC is reportedly inconsistent. We hypothesized that these inconsistencies could be attributed to several variables: (i) suboptimal numbers of MSC infused, (ii) inter-donor variations in the quality of the marrow harvest, or (iii) varying ratios of MSC-subpopulations leading to functional differences in bulk cultures. To address this concern, we used immortalized clonal populations of canine MSC to provide a consistent product for infusion. First, we demonstrated that their in vitro immunosuppressive potential was comparable to primary MSC. Next, we tested their ability to prevent GVHD and allograft rejection in the canine dog-leukocyte antigen (DLA)-haploidentical hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) model. Results indicated that even though clonal MSC could be produced with high efficiency, and were infused frequently and in high numbers, they failed to either mitigate or prevent GVHD, or decrease the likelihood of rejection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Immortalized clonal populations of bone marrow-derived MSC

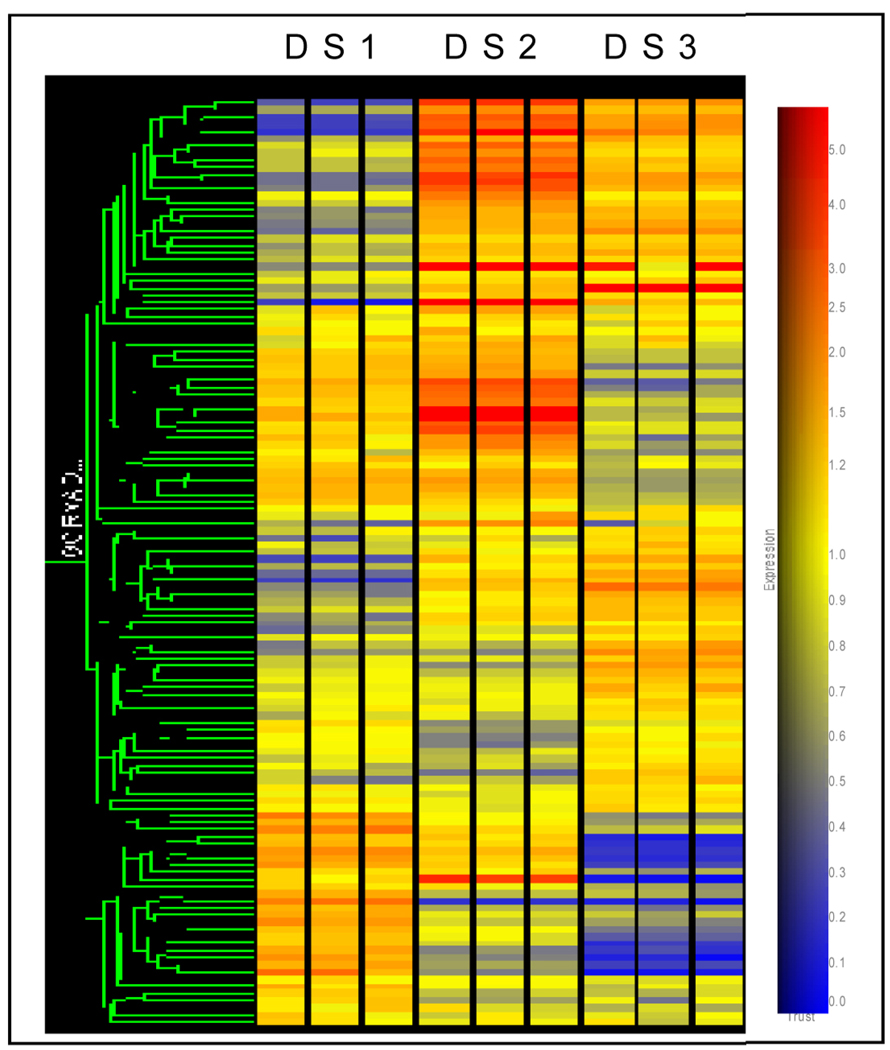

Clonal MSC lines were generated from marrow derived from one donor dog according to procedures previously described for human MSC lines [20]. In brief, canine marrow-derived mononuclear cells were depleted of hematopoietic lineage cells by immune absorption after incubation with anti-CD45 antibodies. The remaining cells were cultured until confluent and then immortalized with a retrovirus containing the human papilloma virus E6/E7 genes. Infected cells were plated at low concentrations and growing clones were isolated with cloning rings. Twenty cloned dog MSC lines designated DS 1–20 were established. Five DS lines were subsequently analyzed in more detail for their ability to suppress the allogeneic MLC in vitro. The 3 lines (DS 1–3) with the strongest suppressive activity in vitro yet the greatest phenotypical differences between each other were chosen for further in vivo experiments. The differences in mRNA profile and cytokine phenotype between DS 1–3 are shown in Figure 1 and Table 2.

Figure 1. Clustering analysis of genes expressed by DS 1–3.

Three separate mRNA preparations were analyzed for each DS line. First, genes on the canine mRNA-arrays (Affymetrix) with raw expression levels >100 were selected. Second, a group of 130 genes with functional annotations allowing them to be classified as “extracellular” by GeneOntology were chosen and found to include secreted factors, cell surface receptors and extracellular matrix proteins. The clustering analysis by the Agilent GeneSpring GX7.3.1 program was based on average linkage, using the Pearson Correlation. DS2 and DS3 differ from DS1, and from each other.

Table 2.

Constitutive production of selected cytokines by immortalized dog marrow stromal cell lines (DS 1–3) and a primary marrow stromal culture (long-term cultures; LTC)

| GM-CSF | IL-4 | IL-6 | IL-8 | IL-10 | MCP-1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DS-1 | ND | 47.6 | 95.7 | 7,857 | 11.8 | 787.7 |

| DS-2 | ND | 55.6 | 72.2 | 6,002 | 10.4 | 2,168 |

| DS-3 | ND | 47.6 | 116.3 | ND | 11.5 | 27.4 |

| LTC | ND | 11.0 | 87.5 | ND | 10.3 | 311.6 |

| Culture media | 16.8 | 17.1 | ND | 166.1 | 5.0 | 20.2 |

Concentrations of cytokines in 5-day conditioned media from immortalized canine marrow stromal cell lines, DS 1–3, and primary marrow stromal cultures (long-term cultures, LTC) were determined using the Lincoplex system (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Concentrations are given in pg/mL. “ND” designates not detectable. Culture media incubated without stromal cells (bottom row) served as a control.

Transcriptome comparison of DS lines

MSC lines DS 1–3 were grown to semi-confluency and RNA extracted [21]. Using canine mRNA-arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA), three separate mRNA preparations were processed for each line. Only those genes with absolute expression values greater than 100 and adequate annotation to be classified as “extracellular”, “chemokines/growth factors”, or “receptors” by Gene Ontology (GO SLIMS) were considered for further analysis. The clustering analysis by the Agilent GeneSpring GX7.3.1 program was based on average linkage, using the Pearson Correlation [21].

Primary MSC cultures (long-term stromal cultures; LTC)

Ex vivo culture conditions for primary canine MSC were adapted from methods described by Le Blanc et al. [2] and Gartner et al. [22]. Briefly, buffy coat cells from marrow aspirates were plated in T-75 flasks (Costar, Cambridge, MA) at 1 to 2 × 106/mL. Adherent cells were grown in LTC medium containing Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM), 12.5% horse serum, 12.5% fetal calf serum, L-glutamine (0.4 mg/mL), sodium pyruvate (1 mmol/L), penicillin (100 U/mL), streptomycin sulfate (100 pg/mL), hydrocortisone sodium succinate (10−6 mol/L), and P-mercaptoethanol (10−4 mol/L) and fed weekly by demidepletion. Stromal layers were maintained at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. After reaching confluency, the adherent layers were trypsinized once and grown to confluency again in a T-225 flask to deplete hematopoietic cells before harvest and infusion. Experiments were performed with 3-week-old LTCs after cells were confluent.

Phenotypical characterization of stromal cell cultures

Based on availability of canine cell-specific monoclonal antibodies, expression levels of informative stromal and cell-lineage-specific markers were assessed by flow cytometry or semi-quantitative polymerase chain-reaction (RT-PCR). For RT-PCR, mRNA was extracted from stromal cell cultures and transcribed into cDNA using µMACS One-Step cDNA kits (Miltenyi Biotec, CA). PCR reactions were performed using 1.1x PCR Master Mix plates (Thermo Scientific, CA) containing Thermoprime Plus DNA Polymerase, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 75 mM Tris-HCl. One hundred nanograms of cDNA template and 2.5 µM of primers (Supplemental Table 1) were added to each reaction. cDNA was amplified during 40 cycles at 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 58–62°C for 45–60 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 1 minute. Amplified products were separated on 2% agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide fluorescence for gene expression. Canine G3PDH was used as a control for input cDNA and was equivalent in all samples. Expression levels of markers determined by flow cytometry (Supplemental Table 1) were compared to those of isotype-matched control antibodies.

Canine mixed lymphocyte cultures (MLC) and mitogen stimulation

105 responder peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were cultured with 105 irradiated (24 Gy), allogeneic, DLA-mismatched stimulator PBMC at a concentration of 106 /mL for 6 days according to established methods [23]. In some experiments, 105 PBMC were stimulated with concanavalin A (conA) at a concentration of 20 µg/ml for 72 hours. Defined numbers (3–50 × 103) of irradiated (24 Gy) clonal MSC or primary marrow stromal cells were added to MLC or conA stimulation cultures at the beginning of culture. Cells were labeled with 1 µCi/well of 3H-thymidine for the final 16 hours of culture, harvested onto glass fiber filters, and counted for isotope incorporation.

To determine whether MSC-conditioned medium (CM) was suppressive in MLC, CM was produced from MSC-lines (5-day culture), concentrated 10-fold and then added to allogeneic MLC in a 1:9-ratio with fresh media. To further assess whether cell contact was required for MSC-mediated suppression of T cell proliferation, irradiated MSC were cocultured with responder and irradiated stimulator peripheral blood mononuclear cells in allogeneic MLC established on 24-well plates. In these experiments, MSC were either cultured in direct contact with responders/stimulators or separated by a 0.3 µm porous membrane on transwell-inserts.

Hematopoietic cell transplantation

Dogs

Litters of random-bred dogs were either raised at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (FHCRC) or purchased from commercial Class A vendors licensed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The dogs weighed from 7.4 to 14.4 (median, 11.4) kg and were between 7 and 56 (median, 9) months old. All dogs were enrolled in a veterinary preventive medicine program that included routine anthelmintics and a standard immunization series [24]. The study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the FHCRC, which has been fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. Littermate donor and recipient pairs were selected on the basis of complete family studies showing haplo-identity for highly polymorphic major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-associated class I and II microsatellite markers [25] and for DLA-DRB1 alleles determined by direct sequencing [26].

Transplant regimen

On day 0, donor marrow was harvested and infused intravenously into allogeneic recipients after a single dose of 9.2 Gy total body irradiation (TBI) delivered at 7 cGy/min (Varian Clinac 4; Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA). The median number of nucleated marrow cells infused was 3.8 ×108 (range, 2.1–9.7 ×108) cells/kg (Table 2). Recipients were given no pharmacological immunosuppression for prevention of GVHD after transplant.

MSC preparation and infusion

MSC lines DS 1–3 and primary, long-term marrow culture (LTC)-derived MSC were expanded to at least semi-confluency ex vivo using T250 culture flasks (Corning, Kennebunk, MN). In adaptation to methods described for culture of human MSC [20,27], ten-percent heat-inactivated fetal calf serum was substituted for pooled dog serum. MSC were then trypsinized, harvested, washed twice and suspended in 0.9% NaCl prior to infusion. The first MSC infusion was given within 30 minutes after marrow graft infusion. Three different MSC regimens were used (Table 2): (1) n=7 recipients; DS1/DS2/DS3 in a 1:1:1 ratio; total dose per infusion, 30 × 106/kg recipient weight; given on 3 days/week during the first week, and on 2 days/week starting the second week after HCT. (2) n=5 recipients; DS1/DS2/DS3 in a 1:1:1 ratio; total dose per infusion, 15 × 106/kg recipient weight; given on 5 days/week. (3) n=3 recipients; primary marrow stromal cells pooled from seven donors; total dose per infusion, 1 × 106/kg recipient weight; given on 3 days/week.

Supportive care and study termination

Prophylaxis with oral antibiotics was given from the day of TBI until the end of the study. Broader antibiotic coverage was administered when neutrophil counts declined to below 0.5 × 103/µL or fever developed. Intravenous fluids were administered when dehydration occurred. Irradiated blood transfusions were given either when platelet counts declined below 5 ×103/µL, or when petechiae and ecchymoses of skin and mucous membranes were observed. Clinical signs of acute GVHD included diarrhea, skin erythema, and elevations of liver enzymes [28]. Dogs were euthanized if they were in poor clinical condition and complete necropsies were performed, which allowed histopathological distinction between GVHD and regimen-related toxicities.

Statistical considerations

The studies were designed to use the fewest dogs necessary to have adequate power to detect differences deemed clinically meaningful in comparison to our historical results [29]. Based on 11 dogs given haploidentical grafts and no pharmacological immunosuppression after transplant, the median survival was 15 days, and long-term survival (>100 days) did not occur. It was predetermined that a group size of 7 dogs treated with MSC provided 80% power to detect an increase in median survival to 37 days, at the 1-sided 0.05 level of significance. Seven dogs also provided 80% power to detect an increase in the proportion of long-term survivors from 5% to 38%, based on an exact binomial test at the 1-sided 0.05 level of significance.

Engraftment and chimerism

Hematopoietic engraftment was assessed by increases in granulocyte and platelet counts following postirradiation nadirs, marrow histology from autopsy specimens, documentation of donor-type hematopoiesis in peripheral blood and marrow by variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) polymorphisms [30,31] and clinical and histologic evidence of GVHD.

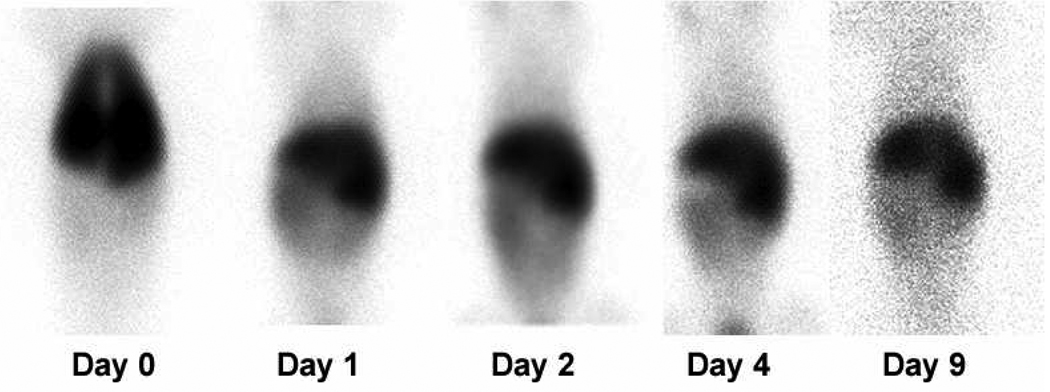

In vivo distribution of 111In-labeled DS1 cells

DS1 cells were labeled in vitro with 111In (30 Bq/cell) [32] prior to injection. Labeled cells were infused into one recipient (G-943) immediately after 8 Gy total body irradiation (delivered at 7 cGy/min as a single fraction). Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) images were obtained immediately after injection, and after 1, 2, 4 and 9 days.

Detection of DS cells in vivo

MSC lines DS 1–3 were generated from one donor dog (DLA-DRB1 3/6), which allowed their detection in blood and tissue samples by VNTR-based polymorphism analysis [30,31]. For this purpose, DNA was extracted from blood and tissue preparations. To detect viable MSC, blood or tissue obtained from recipients at different time points after MSC infusion were cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated dog serum, which allowed for out growth of the immortalized cells. After 72 hours of initial culture, non-adherent cells and debris were rinsed off, and adherent cells were expanded for 7–14 days. Adherent layers were then trypsinized prior to DNA-extraction and chimerism analysis.

RESULTS

Transcriptome comparison of DS lines

In DS lines 1–3, 130 genes with absolute expression values greater than 100 and adequate annotation to be classified as “extracellular”, “chemokines/growth factors”, or “receptors” by Gene Ontology (GO SLIMS) were considered for analysis. The “clustering analysis” of the relative expression of these 130 selected genes shows that the three DS lines differ substantially from each other with respect to their mRNA expression profiles (Figure 1). The complete data set showing transcriptomes for these lines using the Affymetrix microarray platform can be accessed online at: http://webapps.fhcrc.org/labs/graf/grantdata.html.

Phenotypic characterization of DS lines and primary marrow stromal cultures

While primary marrow stromal cultures (long-term marrow cultures; LTC) showed variable expression of hematopoietic lineage markers CD13, CD14 and CD45, these markers were undetectable in DS lines 1–3 (Table 1). In contrast, markers widely associated with cultured human MSC [33,34], such as CD29 (integrin β1-chain), CD73 (ecto-5'-nucleotidase) and CD90 (Thy-1), were consistently expressed by DS 1–3 and by most LTC. Moreover, CD105 (endoglin) was variably expressed by the different LTC tested and consistently expressed by all three DS lines. The three DS lines did not express DLA-class II or CD34.

Table 1.

Phenotypic characterization of immortalized dog marrow stromal cell lines (DS 1–3) and randomly selected primary marrow stromal cultures (long-term cultures; LTC 1–5)

| Marker | Detection Method | MSC Type Tested | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DS1 | DS2 | DS3 | LTC1 | LTC2 | LTC3 | LTC4 | LTC5 | ||

| MHC-class II | FC | − | − | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| CD10 | RT-PCR | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | + |

| CD13 | RT-PCR | − | − | − | ++ | ++ | +++ | − | +++ |

| CD14 | FC | − | − | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| CD29 | RT-PCR | + | +++ | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ |

| CD34 | FC | − | − | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| CD45 | FC/ RT-PCR | − | − | − | +++ | ++ | − | − | + |

| CD73 | RT-PCR | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++ |

| CD90 | FC/ RT-PCR | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | − | − |

| CD105 | RT-PCR | ++ | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | − | − |

| CD106 | RT-PCR | + | − | − | + | − | ++ | − | − |

Expression levels of informative stromal cell- and lineage-specific markers by marrow-derived stromal cell lines (DS 1–3) and five randomly selected primary marrow stromal cultures (LTC 1–5) were assessed by semi-quantitative polymerase chain-reaction (RT-PCR) and flow cytometry (FC) as described in “Materials and Methods”. Expression levels of markers of interest were estimated in relation to that of the housekeeping gene, G3PDH, and isotype-matched control antibodies for RT-PCR and FC, respectively. “ND” designates ‘not done’; “MSC”, ‘mesenchymal stromal cells’; “DS”, dog stromal cell line; “MHC”, ‘major histocompatibility complex’. Expression levels: (+++), strong; (++) intermediate; (+) weak; (−) absent.

Constitutive production of cytokines by DS cells and primary marrow stromal cells

The three DS lines were assayed for cytokine production using the Lincoplex system (Millipore, Billerica, MA). All three lines expressed low, but consistent levels of IL-4, IL-6 and IL-10 and did not secrete detectable levels of GM-CSF, INFγ, CXCL1, IL-2, IL-15, IL-18, or TNFα (Table 2). DS1 and DS2 expressed high levels of IL-8, whereas DS3 produced undetectable levels of IL-8. DS1 and DS2 showed a three-fold difference in MCP-1 production. Hence, in terms of production of this limited panel of cytokines, DS1 and DS2 were more similar, differing considerably from DS3. The 12 cytokines assayed were also represented on the Affymetrix microarrays, and two of them, IL-8 and MCP-1, differed in constitutive expression level in DS3 in contrast to the other two lines. Hence, the transcriptome analysis lent weight to cytokine results and supported the concept of functional heterogeneity among the generated clonal MSC lines. Except for non-detectable levels of IL-8, the cytokine profile of primary marrow stromal cells (LTC) was similar to that of DS 1–3.

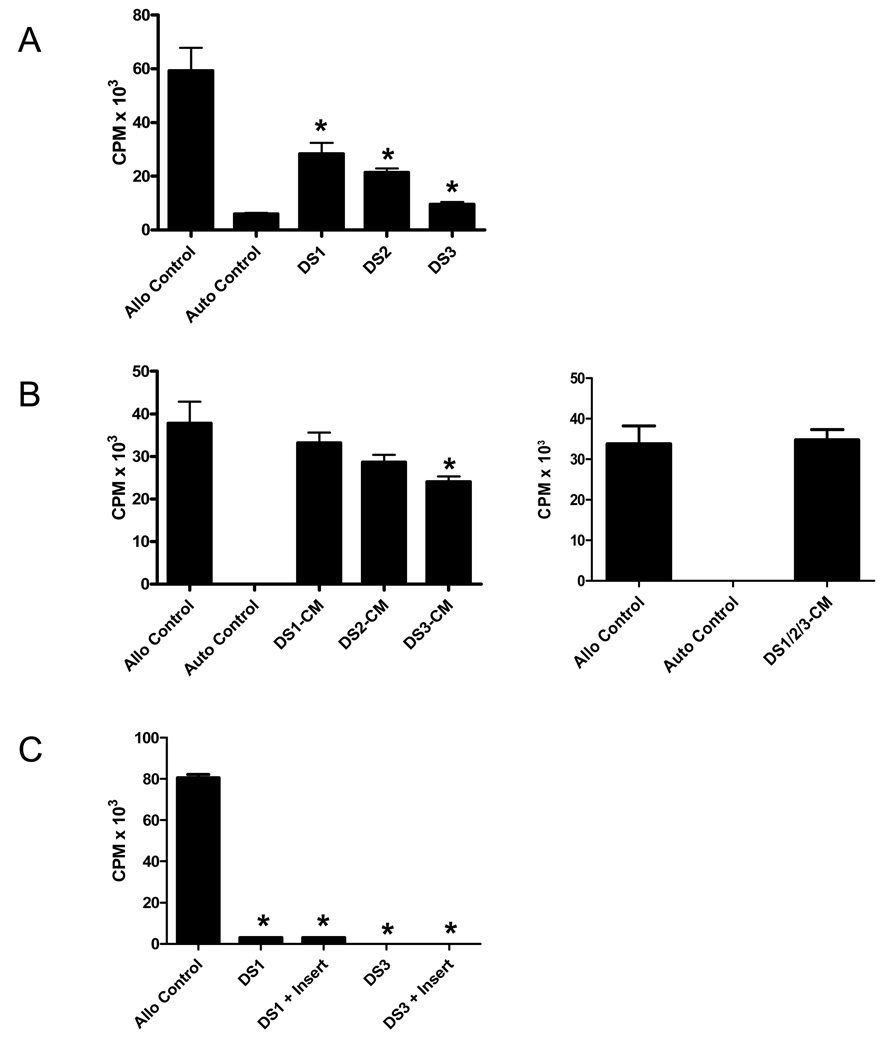

Suppression of alloantigen-driven T-cell proliferation by DS cells

DS1, DS2 or DS3 cells were added at the initiation of allogeneic MLC at a 1:2 DS cell/responder cell ratio (Figure 2A). The results indicated that the three DS lines had variable inhibitory effects on T cell proliferation. While DS3 resulted in >80% suppression in MLC, DS1 or DS2 resulted in 50–70% suppression.

Figure 2. Inhibition of T cell proliferation in canine allogeneic mixed lymphocyte cultures (MLC) by different marrow stromal cell lines (DS 1–3) under contact and non-contact conditions, and by stromal cell-conditioned media.

(A) Standard MLCs were set up using peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from unrelated, dog-leukocyte antigen-mismatched dog pairs. Different MSC-lines, designated DS1-DS3, were irradiated and added at the initiation of MLC at 2:1 responder/MSC ratios. All three DS lines tested had suppressive effects on T cell proliferation. (B) Five-day DS cell-conditioned medium (CM) was produced, concentrated 10-fold and then added to allogeneic MLC in a 1:9-ratio with fresh media. Left panel, results for CM from individual DS-lines. Right panel, results for CM produced by coculture of the three DS-lines (DS1/2/3-CM). (C) DS1 or DS3 cells were irradiated and cocultured with responder and irradiated stimulator PBMC in allogeneic MLC established on 24-well plates. DS cells were either cultured in direct contact with responders/stimulators or separated by a 0.3 µm porous membrane on transwell-inserts (+ Insert). “Allo Control”, allogeneic MLC without addition of DS cells; “Auto Control”, MLC without addition of DS cells using autologous responder and stimulator cells. Shown is one of 3 representative experiments. Results for each experimental condition represent the mean ± standard error of the mean of 6 replicate wells. (*) indicates a statistically significant decrease in proliferative activity compared to Allo Controls (p<0.05; Mann-Whitney test, two-tailed).

MSC-conditioned media (CM) were then tested for their ability to suppress T cell proliferation in allogeneic MLC. For this purpose, 5-day CM was produced and 10-fold concentrated prior to addition to MLC at the initiation of culture (final MSC-CM concentration, 1x). As shown in Figure 2B, MSC-CM was only minimally effective in suppressing the allogeneic reaction, with DS3-CM having the strongest impact (approximately 25% suppression). CM produced by coculture of three DS-lines (DS1/2/3-CM) was equally ineffective in suppressing the proliferative response as CM derived from culture of individual DS-lines (Figure 2B).

Suppression of T cell proliferation by DS cells is contact-independent

To determine whether the relative lack of suppression of T cell proliferation with MSC-CM was due to the lack of cell-contact, transwell-experiments in which DS1 or DS3 cells were set up in the upper chamber and separated by a porous 0.3 µm membrane from the MLC in the lower chamber (Figure 2C). DS cells separated from responder and stimulator cells were as effective in suppressing the allogeneic MLC as DS cells added directly to responder and stimulator cells.

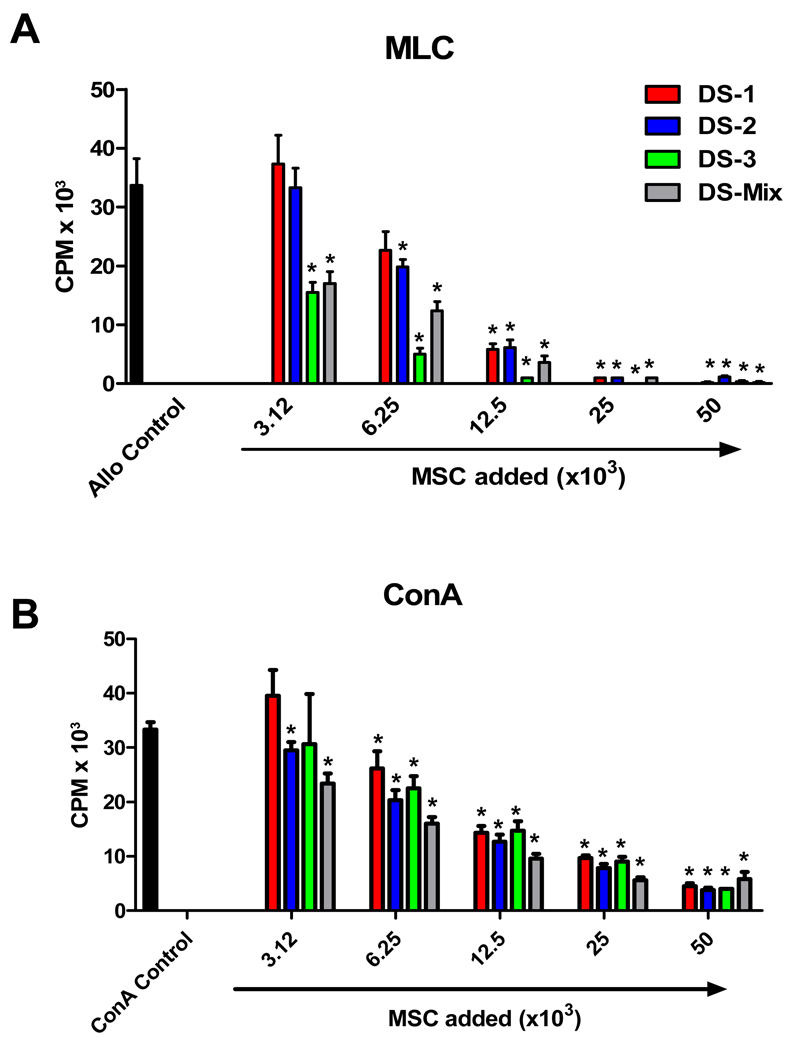

DS cells suppress alloantigen and mitogen-stimulated T cell proliferation in a dose-dependent fashion

DS1, DS2 and DS3-cells, used singly or in combination (DS1/DS2/DS3 in 1:1:1 ratios; DS-Mix), were added to allogeneic MLC (Figure 3A) or mitogen-stimulated PBMC (Figure 3B) in graded numbers. The inhibition of T cell proliferation by DS-cells was cell dose-dependent, with DS3 cells and the DS-Mix having the strongest suppressive effects. Allogeneic MLC performed with titrated numbers of DS1/DS2/DS3 (DS-Mix) in the presence of the prostaglandin-synthesis inhibitor indomethacin (20 µM) reversed DS-cell-mediated suppression of T cell proliferation by 32–56%, suggesting a partial role of prostaglandin-E in DS-cell-mediated suppression of T cell proliferation.

Figure 3. Canine marrow stromal cell lines, DS1, DS2 and DS3, inhibit alloantigen and mitogen-induced T-cell proliferation in a dose-dependent fashion.

Different numbers (3.12– 50.0 × 103) of DS1, DS2 and DS3 cells, used singly or in combination (DS1/DS2/DS3 in 1:1:1 ratio; DS-Mix) were irradiated and added to 105 canine peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) that were stimulated with 105 irradiated allogeneic stimulator PBMC in allogeneic mixed leukocyte culture (MLC) or concavalin A (ConA). Shown are one of 5 representative experiments using individual DS-lines, and one of 2 representative experiments using the DS-Mix. Results for each experimental condition represent the mean ± standard error of the mean of 6 replicate wells. (*) indicates a statistically significant decrease in proliferative activity compared to controls cultured without DS-cells (p<0.05; Mann-Whitney test, two-tailed).

In vivo distribution of 111In-labeled MSC

To better understand the in vivo distribution of immortalized marrow stromal cells, DS1 cells were labeled with 111In and injected intravenously into one beagle dog. The distribution of the label was then monitored over time using a gamma-camera. Based on the assumption that the detected radioactivity was associated with DS1 cells, we found that DS1 cells accumulated in the lung immediately after infusion (day 0), but then left the lung within 24 hours and preferentially redistributed to liver and spleen; weaker signals were detectable in bone marrow and gut (Figure 4). Residual label in liver and spleen could be detected as long as 9 days after infusion.

Figure 4. In vivo distribution of 111In-labeled DS1 cells in a beagle dog (G-943).

DS1 cells were labeled with 111In in vitro and then injected into a beagle dog immediately after 8 Gy total body irradiation (delivered at 7 cGy/min as a single fraction). The dose of labeled and subsequently injected DS1 cells was 28 × 106/kg recipient weight. Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) images were obtained immediately after injection, and after 1, 2, 4 and 9 days. Shown are anterior views in cranio-caudal (top to bottom) orientation.

Infusions of DS cells or primary marrow stromal cells after DLA-haploidentical marrow transplantation do not prevent GVHD or graft rejection

Dogs given DLA-haploidentical marrow grafts without pharmacological postgrafting immunosuppression (n=11) have a median survival of 15 (range, 13–25) days (summarized in Table 3) [29]; seven recipients (64%) rejected their grafts and four (36%) engrafted with ensuing lethal GVHD. Based on this historical experience, we asked the questions whether postgrafting MSC infusions, by virtue of their putative immunosuppressive effects, may (i) increase rates of engraftment and (ii) mitigate GVHD after engraftment. Thus, MSC were infused after transplant according to the three regimens detailed in ‘Materials and Methods’ (Table 3). Three dogs (dogs no. 13–15) were given primary, LTC-derived MSC that were pooled from seven different marrow donors. Even though the doses of primary MSC were substantially lower than those of DS 1–3 cells administered (3 × 106/kg/week vs. 60–90 × 106/kg/week), they were consistent with MSC doses given in clinical GVHD treatment studies [17,18].

Table 3.

Graft composition and outcome of DLA-haploidentical marrow transplants with and without MSC infusions following 9.2 Gy TBI

| Dog # |

Donor ID |

Recip. ID |

Recip. Weight (kg) |

DLA-DRB1 | Bone Marrow Cell Doses | MSC Treatment | Rejec- tion |

Clinical and Histological GVHD |

Survival (Days) |

Hemato- poietic Chimerism at Necropsy |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor | Recip. | MSC | TNC (×108/ kg) |

CD34 (×106/ kg) |

CD3 (×107/ kg) |

MSC Type |

Number of Doses/ Week |

Single Dose (×106 cells/kg) |

Skin | Liver | Gut | |||||||

| 1 | G-897 | H-003 | 13.2 | 3/6 | 3/9 | 3/6 | 3 | 0.9 | 1.02 | DS1/2/3a | 2–3 | 30 | No | Yes | Yes | 17 | Donor | |

| 2 | G-993 | G-988 | 12.6 | 6/9 | 9/17 | 3/6 | 2.1 | 0.42 | 1.28 | DS1/2/3 | 2–3 | 30 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 18 | Donor |

| 3 | G-896 | H-006 | 14.3 | 9/20 | 6/20 | 3/6 | 3.8 | 2.28 | 1.44 | DS1/2/3 | 2–3 | 30 | Yes | 18 | Host | |||

| 4 | H-030 | H-029 | 13.4 | 3/22 | 20/22 | 3/6 | 5.5 | 1.1 | 2.53 | DS 1/2/3 | 2–3 | 30 | No | Yes | Yes | 18 | Donor | |

| 5 | H-098 | H-097 | 9.1 | 2/15 | 2/17 | 3/6 | 3.6 | 0.36 | 1.22 | DS 1/2/3 | 2–3 | 30 | Yes | 18 | Host | |||

| 6 | H-095 | H-096 | 10.6 | 2/3 | 2/15 | 3/6 | 3.8 | 1.52 | 2.55 | DS 1/2/3 | 2–3 | 30 | Yes | 16 | Host | |||

| 7 | H-092 | H-093 | 7.4 | 3/9 | 9/15 | 3/6 | 7.1 | 4.26 | 4.47 | DS 1/2/3 | 2–3 | 30 | NE | 3 | NE | |||

| 8 | H-101 | H-100 | 11.5 | 9/17 | 9/15 | 3/6 | 6.8 | 5.44 | 3.67 | DS 1/2/3 | 5 | 15 | Yes | 18 | Host | |||

| 9 | H-139 | H-130 | 7.8 | 15/22 | 19/22 | 3/6 | 5.0 | 6.5 | 2.8 | DS 1/2/3 | 5 | 15 | Yes | >280** | Host | |||

| 10 | H-053 | H-048 | 9.2 | 20/22 | 3/22 | 3/6 | 9.7 | 5 | 0.97 | DS 1/2/3 | 5 | 15 | No | Yes | 14 | Donor | ||

| 11 | G-550 | H-098 | 10.4 | 2/9 | 2/15 | 3/6 | 8.6 | 19.8 | 2.84 | DS 1/2/3 | 5 | 15 | No | Yes | 13 | Donor | ||

| 12 | G-550 | H-099 | 14.5 | 2/9 | 2/15 | 3/6 | 2.3 | 1.16 | 2.07 | DS 1/2/3 | 5 | 15 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 18 | Donor |

| 13 | H-178 | H-176 | 11.4 | 14/15 | 6/14 | * | 3.7 | 2.22 | 2.52 | Primaryb | 3 | 1 | No | Yes | Yes | 14 | Donor | |

| 14 | H-180 | H-175 | 9.5 | 6/9 | 6/14 | * | 3.5 | 2.8 | 3.74 | Primary | 3 | 1 | Yes | 25 | Host | |||

| 15 | H-180 | H-179 | 11.5 | 6/9 | 6/14 | * | 5 | 5 | 4.9 | Primary | 3 | 1 | Yes | 24 | Host | |||

| Median | 11.4 | 3.8 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 18 | |||||||||||||

| Without MSC infusions: Historical data [29] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Dogs studied | Recip. Weight (kg) |

Bone Marrow Cell Doses Median (Range) |

Rejec tion N (%) |

GVHD N (%) |

Median Survival Days (Range) |

||

| TNC (×108/ kg) |

CD34 (×106/ kg) |

CD3 (×107/ kg) |

|||||

| N=11 | 10.1 (6.5–15) |

3.1 (1.0– 4.4) |

2.8 (2.0– 4.9) |

1.3 (1.2– 2.9) |

7 (64) |

4 (36) |

15 (13–25) |

The DLA-DRB1 types of the different primary MSC donors were as follows: 1/6, 3/9, 3/15, 6/9, 9/17, 9/27, and 15/22.

Dog rejected and, after a long duration of profound pancytopenia, survived with autologous hematopoietic recovery.

DS cell lines 1–3 were always infused at a 1:1:1 ratio.

Primary MSC products in all 3 treated dogs were generated from 7 different donors as described in ‘Methods’, pooled, and infused at approximately equal ratios. MSC, designates mesenchymal stromal cells; DS, dog stromal cell line; DLA, dog leukocyte antigen; TBI, total body irradiation; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; TNC, total nucleated cells; NE, not evaluable.

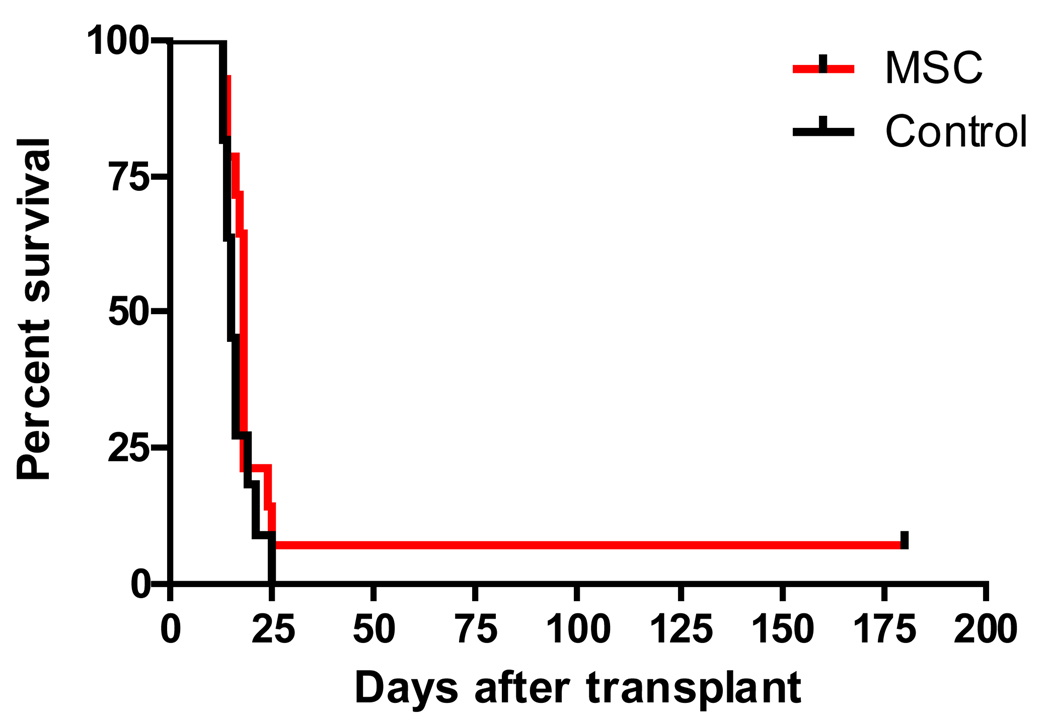

Compared to historical controls transplanted according to similar supportive care standards, postgrafting MSC infusions did not significantly improve survival (15 [range, 13–25] days vs. 18 [range, 3–>280] days), rates of rejection (64% vs. 50%) and rates of GVHD (36% vs. 50%) (p=0.69; Fisher's Exact test) (Table 3). One dog (H-093) died on day 3 after transplant from acute gastrointestinal toxicity related to the conditioning regimen and, therefore, was not evaluable for rejection or GVHD. One dog treated with DS cell infusions (H-130) rejected the marrow graft and survived with autologous hematopoietic reconstitution. Even though numbers were too small for meaningful intergroup comparisons, there was no MSC regimen that appeared effective in preventing the two major endpoints of this clinical study namely, rejection and GVHD. While 3 of 12 recipients given DS cell infusions had received DLA-haploidentical MSC (Table 3), 9 recipients had received fully mismatched MSC. There was no indication that DLA-compatibility between the MSC-product and the recipient had an effect on rates of rejection and GVHD. The Kaplan-Meier survival curves for MSC-treated recipients and historical controls are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Survival of dogs prepared with 9.2 Gy total body irradiation followed by bone marrow transplantation from DLA-haploidentical donors.

No pharmacological immunosuppression was given after transplant. (MSC) marrow stromal cell infusions were given after transplant (n=15). (Control) No MSC infusions were given after transplant (n=11) [29]. One dog given MSC (H-130; see also Table 2) rejected the graft and, after prolonged myelosuppression, survived with autologous hematopoiesis (absolute neutrophil and platelet counts exceeded 0.5 × 103/µL and 20 × 103/µL on days 40 and 56 after transplant, respectively). Survival in the two groups was not significantly different (p=0.18; log-rank test).

Detection of MSC in blood and tissues

Of the 12 recipients given combined infusions of DS 1–3 cells, seven recipients were analyzed for in vivo detection of MSC after infusion (Table 4). Immediately after intravenous infusion, DS cells were detected in the blood by PCR in only 1 of 7 recipients evaluated. At 24, 48 and 72 hours after infusion, PCR products specific for DS cells could be detected in 3 of 6, 1 of 4, and 1 of 4 recipients, respectively, that were evaluated. However, after 7–14 days DS signals could be detected in the blood of all seven recipients. Tissue samples obtained from six recipients at necropsy were also subjected to PCR analysis (Table 4). Without prior ex vivo expansion of stromal elements, DS cell-specific signals were not detected in any of the samples tested. However, after ex vivo expansion DS cell-specific signals were seen in bone marrow, lung and spleen in 2 of 6 dogs evaluated. None of the dogs infused with DS cells showed clinical or histopathological evidence of tumor formation even though cells were immortalized and clonal in nature.

Table 4.

Detection of third-party DS cells in blood and tissues

| Dog | Rec. ID | Blood or Tissue | MSC Detectiori |

Necropsy | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enriched for MSC | In Blood (Hours after Infusion) | In Tissue at Necropsy | ||||||||||||

| # | Prior to Detection by VNTR |

0 | 24 | 48 | 72 | BM | Lung | Liver | Spleen | LN | Day after Transplant |

BM Cellularity (%) |

Chimerism | |

| 1 | H-003 | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | 17 | 50 | Donor | ||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ng | No | No | |||||||

| 2 | G-988 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | 18 | 50 | Donor | |||

| Yes | Yes | No | ng | ng | ng | No | ||||||||

| 3 | H-006 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | 18 | 5 | Host | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ng | Yes | ng | ||||||

| 4 | H-029 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | 18 | 80 | Donor | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | ||||||

| 5 | H-097 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | 18 | 0 | Host |

| Yes | Yes | No | No | No | ng | ng | ng | ng | ng | |||||

| 6 | H-096 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | 16 | 0 | Host |

| Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | |||||

| 7 | H-130 | No | No | No | No | No | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Alive | N/A | Host |

| Yes | Yes | No | No | No | ||||||||||

Mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC) lines DS1-3 were generated from one donor dog, which allowed their detection in blood and tissue samples by VNTR-based polymorphism analysis. For this purpose, DNA was extracted from unmodified or MSC-enriched white blood cell (WBC) and tissue preparations. To enrich for viable MSC, WBC obtained from recipients at different time points after MSC infusion, or minced tissue samples obtained at necropsy were cultured in RPMI media supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated dog serum on 12 well-plates. After 72 hours of initial culture, non-adherent cells and debris were rinsed off, and adherent cells were expanded for 7–14 days. Adherent layers were then trypsinized prior to DNA-extraction and subjected to chimerism analysis as described in “Materials and Methods’. In cases where DS cells were detectable by chimerism analysis after ex vivo expansion of adherent stromal cells (“Yes”), DS cell-specific signals consistently exceeded 80%.

‘BM’ designates bone marrow; ‘LN’, lymph node; ‘ng’, no growth; ‘N/A’, not applicable.

DISCUSSION

By administering third-party, bone marrow-derived MSC in large numbers and at high frequency after DLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation, we hoped to prevent or at least mitigate acute GVHD. In addition, by giving bone marrow that was not supplemented with a T cell-rich buffy-coat and by not using pharmacological immunosuppression after transplant, this well-established preclinical model allowed us to use graft-rejection as an additional read-out for MSC-mediated immunosuppression in vivo.

The majority of recipients were given a combination of three different marrow stromal cell lines (derived from one donor dog) that shared phenotypical features associated with human MSC [33,34] and the ability to suppress allogeneic T cell proliferation in vitro. In fact, their T cell suppressive potential in vitro was similar to or exceeded that observed with primary LTC-derived marrow stromal cells [12]. Analogous to what has been reported by others with primary MSC in vitro, T cell suppression by DS cells was both unrestricted by antigens encoded by the MHC and contact-independent. Even though DS cells suppressed the T cell proliferative response to alloantigen in a contact-independent manner, DS cell conditioned medium was only minimally suppressive. This finding suggested that soluble factors released during the allogeneic immune response may induce MSC to release a soluble mediator that interferes with T cell function. Several soluble factors, including transforming growth factor-β, hepatocyte growth factor and prostaglandin E2, among others, have been proposed to mediate suppressive effects of human MSC [35–37] and canine MSC [12] in vitro. Our findings also suggest that prostaglandins are involved in DS-mediated immunosuppression in vitro.

Although all three DS lines used in our study suppressed alloantigen and mitogen-induced T cell proliferation in vitro, they differed from each other with respect to their immune-phenotype, mRNA expression profile and repertoire of secreted cytokines. The use of MSC products composed of three “phenotypically” different MSC lines isolated from the same LTC, was done to provide an unlimited amount of a consistent cell product for experimental use that would mimic the heterogeneous composition of primary MSC.

Our results in this established canine model showed that, compared to historical controls (n=11) given 9.2 Gy TBI and DLA-haploidentical marrow grafts without MSC infusions after transplant, recipients of MSC (n=15) experienced similar rates of marrow graft rejection. Moreover, all seven MSC recipients which had donor marrow engraftment (50%) developed vicious and rapidly fatal acute GVHD, identical to the experience with historical controls. As a result, survival curves for MSC-treated dogs and controls were virtually superimposable. Even though a meaningful subgroup analysis was limited by small numbers, there was no MSC regimen that appeared effective in preventing the two major endpoints of this preclinical study, rejection and GVHD. Primary MSC were also ineffective in preventing or treating GVHD and rejection. This finding was consistent with a recently published study by Lee et al. [12] showing that donor-derived primary MSC did not prevent marrow graft rejection after DLA-identical HCT. There was also no indication in our study that the degree of DLA-compatibility between MSC products and recipients affected rates of rejection and GVHD. Finally, it is important to emphasize that, since therapeutic benefits associated with MSC infusions were not found, a significant bias related to the use of historical controls appears unlikely.

Additional analysis showed that 111In-labelled DS1 cells accumulated in the lungs immediately after intravenous infusion and, within 24 hours, redistributed to liver, spleen and bone marrow. Hence, the in vivo distribution of DS1 cells was similar to that described for primary marrow-derived MSC studied in other animal models [38,39]. In addition, the in vivo distribution of DS1 cells in this irradiated dog was not different from that in two non-irradiated dogs studied previously (not shown). A limitation of this analysis, however, was the fact that the distribution of the 111In-label may not have been indicative of viable cells since detection of 111In-signals in parenchymal organs could be due to retention of free 111In-label by macrophages. We therefore sought to detect viable DS cells in various organs at the time of necropsy. For this purpose, stromal cells were expanded from organ samples prior to subjecting them to DS cell-specific PCR analyses. Even though expansion of stromal cells from organ samples was not uniformly successful, DS cells could be expanded from the lungs, spleen and marrow of two dogs. These limited data suggested that, after high-dose irradiation of recipients, allogeneic DLA-mismatched DS cells could migrate to and survive in parenchymal organs for several days after infusion. Since detection of DS cells was virtually impossible in organ samples and PBMC without ex vivo expansion of stromal cells, the relative frequency of circulating and tissue-based DS cells after infusion appeared to be low.

In conclusion, our results obtained in the clinically relevant canine model of allogeneic HCT indicate that marrow-derived clonal and primary MSC, even though strongly immunosuppressive in vitro, have no identifiable immunosuppressive activity in vivo. MSC were administered frequently and in doses typically undeliverable in clinical transplantation; however, the MSC regimens used in this study failed to prevent graft rejection and GVHD, the two major immunological barriers of allogeneic transplantation. It is possible that the DS lines used in our study were not representative of primary MSC used in and associated with successful treatment of GVHD in clinical studies [17]. However, outcomes with primary MSC in our study were not different from those with DS cells. Due to the rigorous nature of the model used, it is also possible that the addition of MSC to a regimen of pharmacological immunosuppression might have been more successful. At the very least, this data emphasizes a disconnect between in vitro and in vivo data. Given that the medical literature tends to favor positive study results, our study should serve as a counterpoint emphasizing that the in vivo immunosuppressive effects of MSC have not been unequivocally defined.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful for the excellent care provided by the technicians of the Shared Canine Resource and by all the investigators who participated in weekend treatments of dogs. We thank Dr. Mike Harkey, Gretchen Johnson and Debe Higginbotham from the NIDDK Clonal Analysis Core for providing chimerism analysis, Michele Spector, DVM, and Jennifer Duncan, DVM, for veterinary support, and Dr. George Sale for his expertise in histopathological evaluations. We further thank Dr. Scott Graves, Stacy Zellmer, and Patrice Stroup for DLA-typing; Dr. Satoshi Minoshima, Dr. Joseph Rajendran and Dr. Sudhakar Pipavath for assistance with the in vivo distribution analysis; Dr. Lynn Graf for assistance with RNA microarray analysis, and Helen Crawford and Bonnie Larson for typing the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), grant nos. AI067770; CA15704, DK056465; Bethesda, MD.

Grant support: The project described was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Award Numbers U19AI067770 (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [NIAID]), P30CA015704 (National Cancer Institute [NCI]), and P30DK056465 (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases [NIDDK]). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, NIAID, NCI, or the NIDDK.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.M.: designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, wrote and finally approved the manuscript. L.G. and A.N: expanded MSC ex vivo and performed all in vitro assays. B.H. performed phenotypical MSC analysis. B.T.S. and R.S.: contributed to study design and data interpretation, edited the manuscript. G.G. and R.A.N.: assisted in data interpretation and edited the manuscript.

Authors’ conflicts of interest. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartholomew A, Sturgeon C, Siatskas M, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells suppress lymphocyte proliferation in vitro and prolong skin graft survival in vivo. Exp Hematol. 2002;30:42–48. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(01)00769-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le Blanc K, Tammik L, Sundberg B, Haynesworth SE, Ringdén O. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit and stimulate mixed lymphocyte cultures and mitogenic responses independently of the major histocompatibility complex. Scand J Immunol. 2003;57:11–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2003.01176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krampera M, Glennie S, Dyson J, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells inhibit the response of naive and memory antigen-specific T cells to their cognate peptide. Blood. 2003;101:3722–3729. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sudres M, Norol F, Trenado A, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells suppress lymphocyte proliferation in vitro but fail to prevent graft-versus-host disease in mice. J Immunol. 2006;176:7761–7767. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung NG, Jeong DC, Park SJ, et al. Cotransplantation of marrow stromal cells may prevent lethal graft-versus-host disease in major histocompatibility complex mismatched murine hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Int J Hematol. 2004;80:370–376. doi: 10.1532/ijh97.a30409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tisato V, Naresh K, Girdlestone J, Navarrete C, Dazzi F. Mesenchymal stem cells of cord blood origin are effective at preventing but not treating graft-versus-host disease. Leukemia. 2007;21:1992–1999. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lazarus HM, Koc ON, Devine SM, et al. Cotransplantation of HLA-identical sibling culture-expanded mesenchymal stem cells and hematopoietic stem cells in hematologic malignancy patients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11:389–398. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.in't Anker PS, Noort WA, Kruisselbrink AB, et al. Nonexpanded primary lung and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells promote the engraftment of umbilical cord blood-derived CD34(+) cells in NOD/SCID mice. Exp Hematol. 2003;31:881–889. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(03)00202-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angelopoulou M, Novelli E, Grove JE, et al. Cotransplantation of human mesenchymal stem cells enhances human myelopoiesis and megakaryocytopoiesis in NOD/SCID mice. Exp Hematol. 2003;31:413–420. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(03)00042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le Blanc K, Samuelsson H, Gustafsson B, et al. Transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells to enhance engraftment of hematopoietic stem cells. Leukemia. 2007;21:1733–1738. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee ST, Jang JH, Cheong JW, et al. Treatment of high-risk acute myelogenous leukaemia by myeloablative chemoradiotherapy followed by co-infusion of T cell-depleted haematopoietic stem cells and culture-expanded marrow mesenchymal stem cells from a related donor with one fully mismatched human leucocyte antigen haplotype. Br J Haematol. 2002;118:1128–1131. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee WS, Suzuki Y, Graves SS, et al. Canine bone marrow derived mesenchymal stromal cells suppress allo-reactive lymphocyte prolifearion in vitro but fail to enhance engraftment in canine bone marrow transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.04.016. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le Blanc K, Rasmusson I, Sundberg B, et al. Treatment of severe acute graft-versus-host disease with third party haploidentical mesenchymal stem cells. Lancet. 2004;363:1439–1441. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lazarus HM, Haynesworth SE, Gerson SL, Rosenthal NS, Caplan AI. Ex vivo expansion and subsequent infusion of human bone marrow-derived stromal progenitor cells (mesenchymal progenitor cells): implications for therapeutic use. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;16:557–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koc ON, Gerson SL, Cooper BW, et al. Rapid hematopoietic recovery after coinfusion of autologous-blood stem cells and culture-expanded marrow mesenchymal stem cells in advanced breast cancer patients receiving high-dose chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:307–316. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.2.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ringdén O, Uzunel M, Rasmusson I, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of therapy-resistant graft-versus-host disease. Transplantation. 2006;81:1390–1397. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000214462.63943.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le Blanc K, Frassoni F, Ball L, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of steroid-resistant, severe, acute graft-versus-host disease: a phase II study. Lancet. 2008;371:1579–1586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60690-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baron F, Lechanteur C, Willems E, et al. Co-transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells might prevent death from graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) without abrogating graft-versus-tumor effects after HLA-mismatched allogeneic transplantation following non-myeloablative conditioning. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.01.011. prepublished online 25 January 2010; doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.01.011- [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin PJ, Uberti JP, Soiffer RJ, et al. Prochymal improves response rates in patioents with steroid-refractory acute graft versus host disease (SR-GVHD) involving the liver and gut: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter phase III trial in GVHD. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16 Suppl #41[abstr.] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roecklein BA, Torok-Storb B. Functionally distinct human marrow stromal cell lines immortalized by transduction with the human papilloma virus E6/E7 genes. Blood. 1995;85:997–1005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graf L, Iwata M, Torok-Storb B. Gene expression profiling of the functionally distinct human bone marrow stromal cell lines HS-5 and HS-27a (Letter to Editor) Blood. 2002;100:1509–1511. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gartner SM, Kaplan HS. Long term culture of human bone marrow cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:4756–4759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.8.4756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raff RF, Storb R, Ladiges WC, Deeg HJ. Recognition of target cell determinants associated with DLA-D-locus-encoded antigens by canine cytotoxic lymphocytes. Transplantation. 1985;40:323–328. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198509000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burroughs L, Mielcarek M, Little M-T, et al. Durable engraftment of AMD3100-mobilized autologous and allogeneic peripheral blood mononuclear cells in a canine transplantation model. Blood. 2005;106:4002–4008. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wagner JL, Burnett RC, DeRose SA, Francisco LV, Storb R, Ostrander EA. Histocompatibility testing of dog families with highly polymorphic microsatellite markers. Transplantation. 1996;62:876–877. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199609270-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wagner JL, Works JD, Storb R. DLA-DRB1 and DLA-DQB1 histocompatibility typing by PCR-SSCP and sequencing (Brief Communication) Tissue Antigens. 1998;52:397–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1998.tb03063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mielcarek M, Roecklein BA, Torok-Storb B. CD14+ cells in granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF)-mobilized peripheral blood mononuclear cells induce secretion of interleukin-6 and G-CSF by marrow stroma. Blood. 1996;87:574–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mielcarek M, Georges GE, Storb R. Denileukin difitoxin as prophylaxis against graft-versus-host disease in the canine hematopoietic cell transplantation model. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:899–904. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Georges GE, Storb R, Bruno B, et al. Engraftment of DLA-haploidentical marrow with ex vivo expanded, retrovirally transduced cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Blood. 2001;98:3447–3455. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.12.3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu C, Ostrander E, Bryant E, Burnett R, Storb R. Use of (CA)n polymorphisms to determine the origin of blood cells after allogeneic canine marrow grafting. Transplantation. 1994;58:701–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hilgendorf I, Weirich V, Zeng L, et al. Canine haematopoietic chimerism analyses by semiquantitative fluorescence detection of variable number of tandem repeat polymorphism. Veterinary Research Communications. 2005;29:103–110. doi: 10.1023/b:verc.0000047486.01458.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bindslev L, Haack-Sorensen M, Bisgaard K, et al. Labelling of human mesenchymal stem cells with indium-111 for SPECT imaging: effect on cell proliferation and differentiation. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2006;33:1171–1177. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keating A. Mesenchymal stromal cells (Review) Curr Opin Hematol. 2006;13:419–425. doi: 10.1097/01.moh.0000245697.54887.6f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bernardo ME, Locatelli F, Fibbe WE. Mesenchymal stromal cells (Review) Ann NY Acad Sci. 2009;1176:101–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aggarwal S, Pittenger MF. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate allogeneic immune cell responses. Blood. 2005;105:1815–1822. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meisel R, Zibert A, Laryea M, Gobel U, Daubener W, Dilloo D. Human bone marrow stromal cells inhibit allogeneic T-cell responses by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-mediated tryptophan degradation. Blood. 2004;103:4619–4621. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rasmusson I, Ringden O, Sundberg B, Le Blanc K. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit lymphocyte proliferation by mitogens and alloantigens by different mechanisms. Exp Cell Res. 2005;305:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gao J, Dennis JE, Muzic RF, Lundberg M, Caplan AI. The dynamic in vivo distribution of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells after infusion. Cells Tissues Organs. 2001;169:12–20. doi: 10.1159/000047856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chin BB, Nakamoto Y, Bulte JW, Pittenger MF, Wahl R, Kraitchman DL. 111In oxine labelled mesenchymal stem cell SPECT after intravenous administration in myocardial infarction. Nucl Med Commun. 2003;24:1149–1154. doi: 10.1097/00006231-200311000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.