Many chemical agents have low solubility which makes their dispersion, admixing and delivery difficult. Ball milling is often used to disperse such materials; however, dry powders are not always convenient for further applications [1]. For liquid hydrophobic materials, such as oil, there is a well established procedure of emulsification which allows for the stable dispersion of microdrops in water [2-3]. In this paper, we discuss a method for converting solid materials into stable aqueous nanocolloids with a particle size of ca 200 nm through simultaneous powerful ultrasonication and layer-by-layer (LbL) polyelectrolyte coating. It is a development of LbL microencapsulation introduced by G. Sukhorukov, E. Donath, F. Caruso, H. Möhwald, et al. [4-10] Most of these works are exploiting the formation of nano/engineered polyelectrolyte shells on pre-formed microtemplates with much larger diameters of 1 to 5 μm [11-18].

There is a number of publications on micronizing drug or dye particles and building LbL shells on them, typically containing 4 to 10 polyelectrolyte bilayers and allowing a slow particle dissolution time from minutes up to 3-4 hours through adjustable capsule wall thickness (wall thickness of 20-50 nm) [9-10, 19]. LbL shell coated dye particles were used as paint additives [11]. Soluble drugs, such as furosemide, nifedipine, naproxen , biotin, vitamin K3 and insulin were mechanically crushed into a dry powder and used for LbL shell assembly at a pH where they have low solubility in order to preserve the drug microcores from dissolution during the preparation [12-15]. Typical particle sizes of such a formulation were 2-10 micrometers [14]. In another approach, LbL microcapsules were assembled on sacrificed micro-cores (2-5 μm CaCO3, MnCO3, or silica). Then these cores were dissolved and the empty shells were loaded with proteins or drugs through pH controlled capsule wall opening [13-15]. Induced drug release is also possible with light responsive capsule opening [16]. Contrary to the first case of solid drug cores, these microshells contained a relatively low amount of loaded materials (1-5 vol %). Laser confocal microscopy allowed for the detailed studying of the structure of such microcapsules, proving the location of the loaded drugs and demonstrating their penetration into cells [17]. However, this successful development did not allow for the capsules to be sized on the nanometer scale.

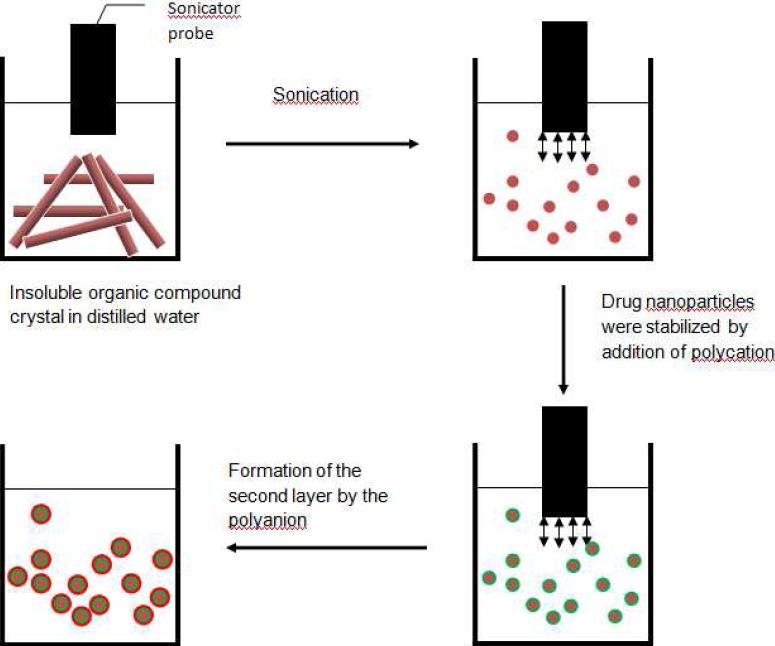

We are describing a method to prepare stable aqueous nanocolloids of low soluble materials (solubility less than 0.005 mg/mL) having particle diameters in the range of 150-250 nm. This approach is based on the powerful sonication of powders of low soluble materials in the presence of a polyelectrolyte which is adsorbing charging particles and preventing smaller and smaller pieces from re-aggregation. At the first preparation step, one has a colloidal dispersion of materials coated with a layer of polycations which provides a surface ξ-potential of ca +35 mV. Deposition of the second anionic polyelectrolyte increases the nanoparticle ξ-potential magnitude to -45 mV, and these well charged nanocolloids remain stable for months (Scheme 1). These colloids may be produced not only in water but also in other polar solvents (such as alcohol, acetone, dimethyl sulfoxide, and formamide). Additional coating with sequential polycation / polyanion layers allows for the building of sophisticated capsule wall architecture for advanced properties (such as targeting, anticoagulant properties such as PEGylation). Nanocolloids of inorganic and organic low soluble materials with content up to 90 wt % and concentration up to 5 mg/mL were prepared with sonicated layer-by-layer technology (SLbL) via alternate adsorption of oppositely charged synthetic or natural polyelectrolytes. Contrary to the traditional LbL microcapsules, we do not need to build thicker capsule walls because the core materials have low solubility, and even with two-layer polycation/polyanion shells, the core dissolution in a large volume of water usually takes 4-10 hours. However, building additional LbL layers allows for a longer release time up to 20 hours [19-20].

Scheme 1.

Representation of solid compound nanoparticulation through sonication assisted layer-by-layer assembly.

Nanocolloids of low soluble anticancer drugs, camptothecin, dexamethasone, tamoxifen, paclitaxel and curcumin with drug content of 80-90 % were prepared through SLbL technology with alternate adsorption of oppositely charged biodegradable polyelectrolytes and proteins. Ultrasonication of the drugs in powder form and simultaneous deposition of the first polycation layer is the key step of SLbL. Drug release rates from such nanocolloids can be controlled by assembling multilayer shells with variable thicknesses. Other low soluble chemicals, including corrosion inhibitors, dyes and insoluble inorganic salts, were also converted to stable nanocolloids for better dispersion in hydrophilic coatings and polymer nanocomposites. Here we present nanocolloid formulation as a general method for converting low soluble or insoluble solid materials into stable nanocolloids.

Materials and methods

Poorly soluble anticancer drugs, such as paclitaxel, curcumin, resveratrol and tamoxifen as well as other organic compounds, such as orange 13, gadolinium contrast agent for MRI (gadopentetate dimeglumine - C28H54GdN5O20), 2-mercaptobenzothiazole and 2,4-diphenylhydrazine were studied for nanoencapsulation. Inorganic compounds for nanocolloids synthesis comprise cupric oxide, cupric carbonate, barium sulfate, iron sulfide and manganese sulfide. Chemicals were purchased as follows: paclitaxel from LC laboratories (Woburn, MA), curcumin from Sabinsa Corporation (Utah, USA), gadopentetate dimeglumine (ViewGam Inc.), resveratrol, tamoxifen, 2-mercaptobenzothiazole and 2,4-diphenylhydrazine (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) were used without further purification. Low soluble materials were added in to water, sonicated until uniform turbid solution, and then polycations were added. Ultrasonicator UIP1000hd (Heilscher-USA Instruments) was used to rupture the solid compounds at a power of 30 W /cm2, and the sonication time varied between 30-60 min. The temperature was controlled at 25 ± 5 °C using an ice bath. LbL assembly was carried out beginning with one of cationic polyelectrolytes, such as poly(allylamine hydrochloride) (PAH), poly(dimethyldiallyl ammonium chloride) (PDDA), chitosan and protamine sulfate (PS). At the second stage of the assembly, anionic sodium poly(styrene sulphonate) (PSS), poly(acrylic acid) (PAA), alginic acid and bovine serum albumin (BSA). TiO2 particles eroded out of sonotrode were separated out by centrifugation at 2,000 rpm for 20 minutes. All of the polyelectrolytes were used at concentration of 2 mg/mL at pH 7-7.4. In general, the sonication assisted LbL coating technique was as follows: ultrasonication was applied to break down solid compounds placed in water. Material re-aggregation was prevented by simultaneous adsorption of polyelectrolytes which provided high ξ- potential of the colloidal particles.

Electrical surface potential (ξ- potential) and particle size measurements (by light scattering) were performed using ZetaPlus Microelectrophoresis (Brookhaven Instruments). Field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM, Hitachi-2007) was used for nanoparticle imaging. Laser confocal microscope (LTCS SP2, Leica Microsystems Inc) was also used to capture images of fluorescently labeled nanocapsules in water dispersion.

Results and discussion

Poorly soluble organic compounds

This technique originated from the works on low soluble anticancer drug nanoparticulation [19-21], but for generality, we also studied nanocolloid production from low soluble anticorrosion agents, MRI gadolinium agent, low soluble dyes, and insoluble inorganic salts such as CuO, CuCO3, BaSO4 and Al(OH)3 (Scheme 2, tables 1-2).

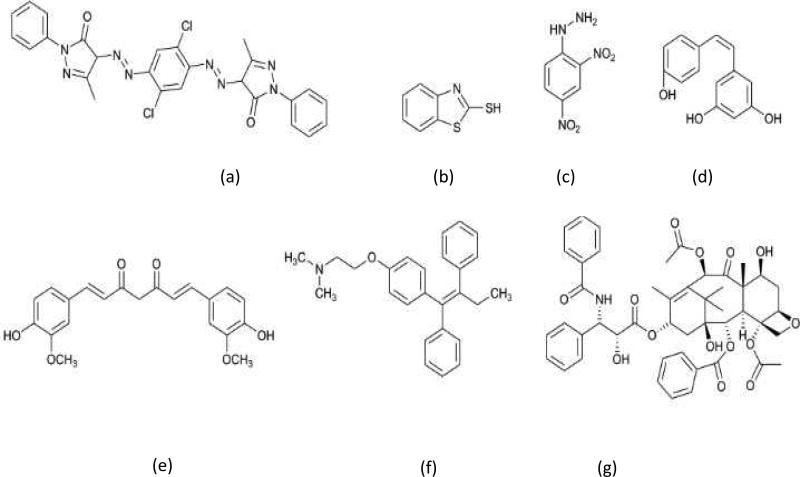

Scheme 2.

Chemical structure of organic compounds a) orange-13, b) 2-mercaptobenzothiazole, c) 2,4-diphenylhydrazine d) resveratrol, e) curcumin, f) tamoxifen and g) paclitaxel

Table 1.

The experimental details for ultrasonication assisted LbL assembly of poorly soluble compounds

| Organic compounds | Initial particle size (μm) | First layer | Second layer | After LbL coating, size (nm) | Release time (hr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paclitaxel | 15 ± 5 | PAH, Chitosan | PSS, Alginic acid | 211 ± 40 | 6 |

| Tamoxifen | 12 ± 7 | PAH, PDDA | PSS, PAA | 220 ± 32 | 6 |

| Curcumin | 18 ± 5 | PAH, PS | PSS, BSA | 107 ± 17 | 5 |

| Resveratol | 180 ± 40 | Chitosan | Alginic acid | 200 ± 30 | 6 |

| Orange 13 | 19 ± 6 | PAH, PS | PSS, BSA | 264 ± 23 | 7 |

| 2,4-Diphenylhydrazine | 82 ± 20 | PAH, PDDA | PSS | 216 ± 29 | 7 |

| 2-Mercaptobenzodiazole | 27 ± 4 | PAH, PS | PSS, BSA | 290 ± 33 | 8 |

Table 2.

The experimental details for ultrasonication assisted layer-by-layer assembly of poorly soluble inorganic salts.

| Inorganic compounds | Particle size (μm) | First layer | Second layer | Particle size after LbL coating (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CuO | 15 ± 23 | PAH, PS | PSS, BSA | 175 ± 20 |

| CuCO3 | 50 ± 17 | PAH, PDDA | PSS | 199 ± 25 |

| BaSO4 | 6 ± 3 | PAH | PSS | 120 ± 50 |

| FeS | 40 ± 8 | PAH | PSS | 160 ± 30 |

| MnS | 50 ± 20 | PAH | PSS | 230 ± 20 |

| Al(OH)3 | 30 ± 15 | PAH | PSS | 225 ± 25 |

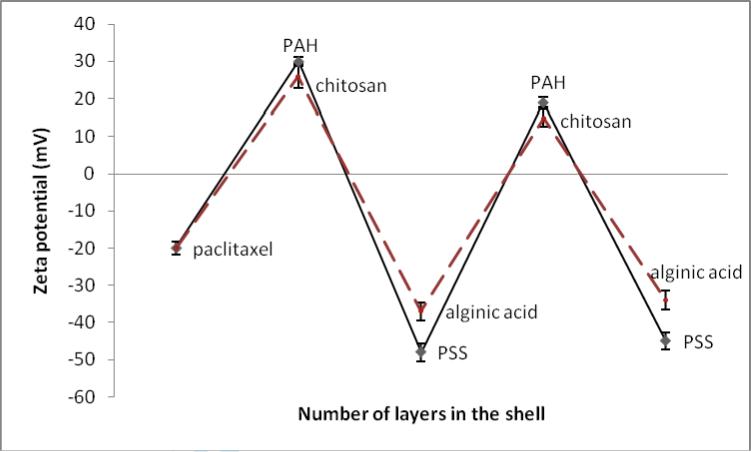

Just after ultrasonication (but before polycation addition) all materials have shown a negative surface charge (ξ-potential was minus 10-20 mV). Colloids were stable during sonication but quickly aggregated after termination of sonication. An addition of polycation to the dispersion during processing resulted in smaller particle sizes and enhanced their surface potential to plus 25-30 mV. A sequential deposition of anionic polyelectrolyte layer allowed further increasing surface ξ- potential magnitude to minus 35-45 mV reaching by this a threshold of colloidal stability. Fig. 1 shows monitoring of ξ-potential of paclitaxel nanoparticles during SLbL coating with two different shell compositions comprising synthetic polyelectrolytes PAH/PSS and biodegradable polyelectrolytes chitosan/alginic acid.

Figure 1.

ξ-potential during paclitaxel nanoparticle LbL coating via alternate adsorption of poly(allylamine hydrochloride) (PAH) / sodium poly(styrene sulfonate) (PSS) and chitosan / alginic acid

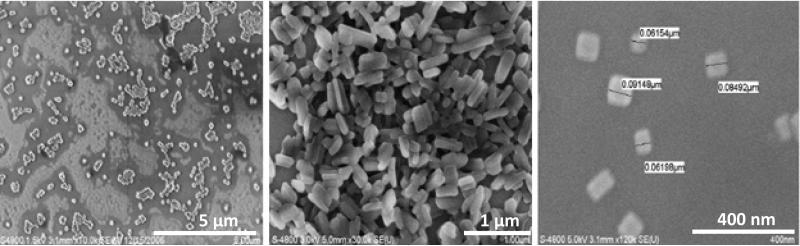

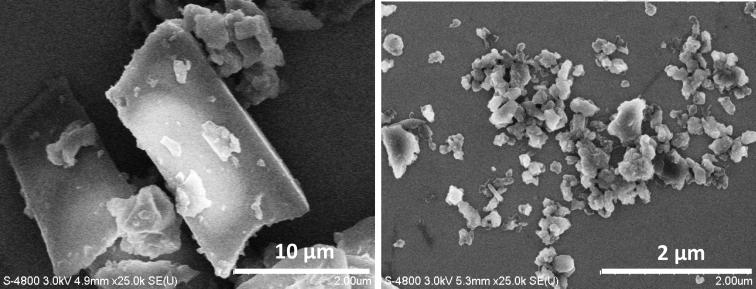

The strongly charged LbL coated nanoparticles repulse, preventing aggregation and maintaining colloidal stability. Fig. 2 shows SEM images of tamoxifen, paclitaxel and curcumin nanoparticles, and Table 1 includes their sizes which are 150 - 220 nm and the shell compositions. It is interesting that the resulted LbL-nanoparticles of a certain compound have a similar shape (round, rod-like, and square), probably reflecting the material crystalline structures. Besides, the shape can be connected with differences in melting / solidifying of different substances. In the initial dry powders, particles were of tens micrometers in their sizes, but after SLbL processing we got rather narrow nanoparticle size distribution; typically ca 15% (Fig. 2 and Table 1).

Figure 2.

Scanning electron microscopy images of (a) tamoxifen nanoparticulation with ultrasonication and LbL coating of (PDDA / PSS), (b) paclitaxel and (c) curcumin nanocolloids coated with (PAH/BSA)2

Due to the very thin polyelectrolyte shell walls of 4-5 nm and solid cores, the resulted nanoparticles have a high holding capacity up to 90 wt %. Different polycation and polyanions may be used for the capsules of varied compositions. Nanocolloids as an end product were stable for at least one month at a concentration up to 1 mg/mL.

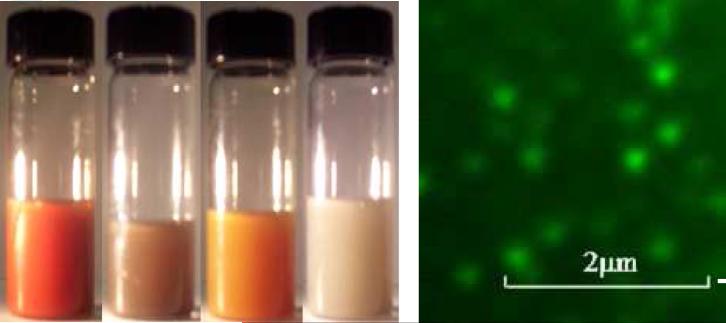

Fig. 3a shows an optical image of stable colloidal solutions. One could see homogeneous dispersions with permanent colors. For tamoxifen, we coated an outermost layer with FITC labeled polycation (PAH) and captured fluorescent images of colloids using a confocal microscope (Fig. 3b). Due to very small tamoxifen particles of ca 220 nm which is below confocal microscope resolution, they are only visible as tiny green dots which are well separated from one another in water. Drug release time was 5-7 hours, and it may be increased by building a thicker capsule wall with 4-6 polycation / polyanion pairs [20-22].

Figure 3.

(a) Image of stable nanocolloids of orange 13, cupric oxide, 2,4-diphenylhydrazine and paclitaxel, and (b) confocal fluorescent image of an aqueous dispersion of LbL paclitaxel nanocolloid coated with chitosan and FITC-labeled BSA.

Paclitaxel, curcumin and tamoxifen (drugs for breast and ovarian cancer) are poorly soluble and their solubility is too small for efficient injection. The micrometer formulations of these drugs cannot enter inside the tumor due to the nanopore cutoff size for the cancer tissue. Therefore, producing stable nanocolloids of these drugs promises their better delivery to the tumor. Another promising medical example is SLbL-encapsulation of MRI gadolinium contract agent (gadopentetate dimeglumine) converting initially 5-8 micrometer particles into stable submicron colloids of 400 ± 100 nm diameter particles.

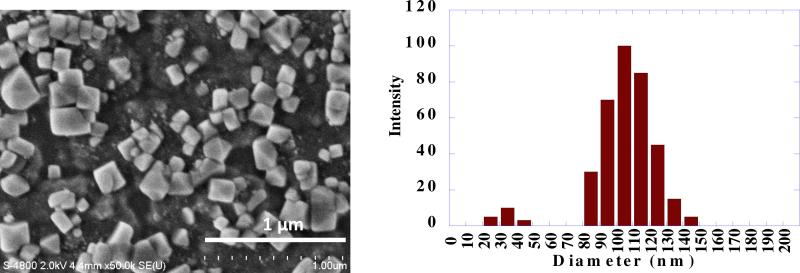

Some poorly soluble dyes and anticorrosion agents were also tested for nanocolloid development (orange 13, 6-mercaptobenzodiazole and 2,4-diphenylhydrazine). They were found to be negatively charged after the initial ultrasonication. During SLbL processing, the particles were coated with positively charged poly(allylamine hydrochloride) (PAH) and negatively charged poly(sodium styrene sulfonate) (PSS) was deposited as a second layer. Ultrasonication assisted LbL assembly reduced the initially micrometer particles to 200-290 nm size particles (Fig. 4 and Table 1). Each dye was checked with a UV spectrophotometer to confirm its color. These colored nanocolloids were stable for months.

Figure 4.

SEM images of orange 13, (a) before and (b) after SLbL coating.

A delivery of these materials through aqueous nanocolloids is more efficient as compared with their solution. The same volume of solution allowed ca. 400 times more LbL nanoparticulated materials as compared to the original saturated solution of these chemicals (2 mg/mL versus ca 0.05 mg/mL).

Insoluble inorganic compounds

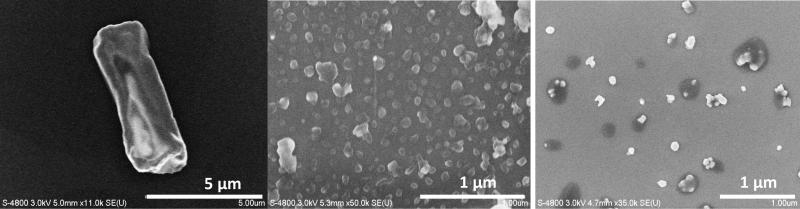

Similar to organic compounds, we also demonstrated the production of inorganic compound nanocolloids. Fig. 6 and Table 2 show reduction from 10-50 micrometer particles in the initial powder to an average of 250 nm diameter nanocolloids with potential of ca -40 mV.

Figure 6.

(a) SEM image of paclitaxel coated with PAH/PSS with average size of 120 ± 30 nm obtained with LbL ultrasonication enhanced with bubbling agent NH4HCO3 used at concentration 1 mg/mL and (b) corresponding curve of particle size distribution.

We studied SLbL nanocolloids from different salts (Table 2). We have sorted inorganic salts in three general groups: oxides, sulfides and hydroxides. Sulfides are the most insoluble inorganic compounds and oxides in general are more soluble (they all are ionic crystals) and both gave stable nanocolloids. Our attempt to prepare nanocolloids from silicon wafers failed, probably, because of more strong bonds in this covalent crystal. Formation of stable nanocolloids from different solid materials may find industrial applications in composite materials.

A similar method to the described approach of sonicated LbL encapsulated was applied to form micrometer size bubbles containing hydrophobic dyes with polyglutomate as interface macromolecules [23]. Poor water soluble molecules also may be driven into LbL microparticles and precipitate there by adjustment polarity or pH gradient [24]. In another approach, a low soluble drug was loaded in nanometer-size porous silica which was then LbL coated with a polyelectrolyte shell [25]. LbL coated submicron size methoxyestradiol crystals were also produced [26]. All these works have shown a good degree of success but they are lacking a generality and formulated particles were of much larger diameter.

Ultrasonication enhanced with bubbling agents

Ultrasonication can be applied to create extreme physical-chemical conditions at the liquid / gas interface while the bulk solution can stay at room-temperature. During high power ultrasonication (20 kHz, 50-100 W) gas bubbles are formed and expanded, followed by cavity implosion and jet formation. This creates very high temperature (up to 5000 K) and high pressure (up to 103 atm) in the center of the cavity, while the bulk solution remains at low-temperature due to localized energy release and high cooling rate. This high pressure and the jet formation crush solid materials into micro and nanoparticles [27-31].

To maximize the ultrasonication capability for nanoparticulation, the bubble nucleation rate is a key parameter. Using NH4HCO3 as a bubbling agent to enhance bubble nucleation allowed us decreasing size of colloid particles closer to 100 nm (Fig. 6). This bubbling agent was completely decomposed and “bubbled-out” during sonication as NH3 and CO2 gases. The size distribution diagram is centered at 120 nm and its width is 60 nm (ca 5% of small ca 8 nm particles are visible in the area of smaller scales; assumingly, there are TiO2 particles released from titanium sonotron). Additionally to the gas concentration in solvent, the bubble nucleation rate dN/dt depends on gas concentration, temperature, surface tension, pressure, hydrophobicity of the substrate surface [31-32]. This equation has two terms describing air dissolved in water and additional bubbling gas:

| (1) |

where C is gas concentration, ΔE = 4πσ3P-2 g(θ)/3 is the energy barrier for the bubble nucleation, T is the surrounding temperature, σ is the liquid/air surface tension. P is pressure; θ is the contact angle of the surface.

Since we are using an aqueous medium for the nanocolloid synthesis, there will be a minute variation for surface tension and contact angle as compared to possible pressure variation (additional 2-3 atm may essentially increase ultrasonication efficiency). So, higher gas concentration through bubbling agents increases nucleation. An increase in pressure will decrease the energy barrier, also resulting in the increase of bubble nucleation, and is thus helpful for the nanoparticle formation. It was found that low wettability of materials (which is the case for more hydrophobic low soluble materials) forms the shape of bubble resulting jet directing to the particle surface which may increase explosion energy [32].

Though the nanoparticulation procedure is reliable, there are number of features which have to be discussed and clarified in future studies:

The role of adsorbed polyelectrolytes may be not only in the particle surface re-charging but may also serve as cleaving agents, filling and widening microcracks caused by sonication. Dependence of the procedure on molecular weight of the used polyelectrolytes may be important.

In all our experiments, electrical surface potential (ξ-potential) of micro/nano particles after ultrasonication (but before polyelectrolyte deposition) was negative. It may be due to partial oxidation of the particle surface under ultrasonication. This assumption has to be checked and control over the depth of such oxidation may request operations in nitrogen atmosphere.

Even increasing ultrasonication power and extending its time did not allow smaller particle sizes: 200-nm diameter was a kind of “magic” barrier for many of our colloidal particles. We suggested that it may be related to the nucleation size of vapor bubbles. This assumption allowed us to decrease colloid particles to 150 nm diameter using agents enhancing bubbling formation (such as NH4HCO3). The process of the bubble nucleation related with materials hydrophobicity has to be analyzed to get even smaller particle sizes.

In many cases, the shape of obtained colloidal nanoparticles reflected the material's crystalline structure (cubic, rectangular for curcumin and paclitaxel) but for some materials spherical (tamoxifen) or irregular nanoparticles were produced. It may be explained by amorphous formation or melting some of the compounds at elevated local temperature due to cavitation effect.

Conclusions

With sonication assisted polyelectrolyte layer-by-layer (SLbL) nano/encapsulation, aqueous nanocolloids of poorly soluble materials were produced with particle size reduced from micrometers in the initial powders to ca 200 nanometers in colloids. Synergy of simultaneous breaking powder particles with ultrasonication and coating them with polycations allowed for the production of smaller particles than just with ultrasonication and provided them with sufficient surface electrical potential for colloidal stability. A better understanding of the physical and chemical impact on the materials during ultrasonication is needed to optimize the SLbL process and reach even smaller colloidal particle size. This technique drastically increases dispersibility and amount of compounds allowed for delivery in small volume of aqueous colloid of low soluble materials ranging from anticancer drugs to anticorrosion agents and inorganic salts. This may diversify products on commercial bases such as pharmaceutical, materials composites, and paints industries. Ultrasonication aided layer-by-layer nanocoating is easy-to-handle and is a scalable-up technique for stable nanocolloids of low soluble materials.

Figure 5.

SEM images of poorly soluble inorganic materials: (a-b) cupric oxide before and after processing and (c) barium sulfate after LbL nano-particularization.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Award R01CA134951 from the National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Hampsey J, De Castro C, McCaughey B, Wang D, Mitchell B, Lu Y. Preparation of micrometer- to sub-micrometer-sized nanostructured silica particles using high-energy ball milling. J. Am. Ceramic Soc. 2004;87:1280–1286. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nilsson L, Bergenstahl B. Adsorption of hydrophobically modified anionic starch at oppositely charged oil/water interfaces. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2007;308:508–513. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2007.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guzey D, McClements D. Formation, stability and properties for multilayer emulsions for application in food industry. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2006;128:227–248. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sukhorukov G, Donath E, Davis S, Lichtenfeld H, Caruso F, Popov V, Möhwald H. Step-wise polyelectrolyte assembly on particle surfaces-a novel approach to colloid design. Polym. Adv. Technol. 1998;9:759–765. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donath E, Sukhorukov G, Caruso F, Davis S, Möhwald H. Novel hollow polymer shells by colloid-templated assembly of polyelectrolytes. Angew. Chem, Int. 1998;37:2202–2209. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980904)37:16<2201::AID-ANIE2201>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antipov A, Sukhorukov G. Polyelectrolyte multilayer capsules as vehicles with tunable permeability. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science. 2004;111:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caruso F. Nanoengineering of Particle Surfaces. Adv. Materials. 2001;13:11–23. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qiu X, Leporatti S, Donath E, Möhwald H. Studies on the Drug Release Properties of Polysaccharide Multilayers Encapsulated Ibuprofen Microparticles. Langmuir. 2001;17:5375–5380. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lvov Y, Antipov A, Mamedov A, Möhwald H, Sukhorukov G. Urease Encapsulation in Nanoorganized Microshells. Nano Letters. 2001;1:125–128. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sukhorukov G. Multilayer Hollow Microspheres. Vol. 5. Citrus Books; 2002. pp. 111–147. book: MML Series. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ai H, Jones S, de Villiers M, Lvov Y. Nanoencapsulation of Furosemide Microcrystals for Controlled Drug Release. J. Controlled Release. 2003;86:59–66. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00322-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheney D, Sukhorukov G. Engineered microcrystals for direct surface modification with layer-by-layer technique for optimized dissolution. Eur. J. Phar. Biopharm. 2004;58:521–527. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Geest B, Sukhorukov G, Möhwald H. The pros and cons of polyelectrolyte capsules in drug delivery. Expert Opinions Drug Deliv. 2009;6:613. doi: 10.1517/17425240902980162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bédard M, De Geest B, Skirtach A, Möhwald H, Sukhorukov G. Polymeric microcapsules with light responsive properties for encapsulation and release. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science. 2010;158:2–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Cock L, De Koke S, De Geest B, Grooten J, Vervaet C, Remon Je., Sukhorukov G, Antipina M. Polymeric Multilayer Capsules in Drug Delivery. Angewandte Chemie. 2010;122:9820–9829. doi: 10.1002/anie.200906266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palankar R, Skirtach A, Kreft O, Bedard M, Garstka M, Gould K, Möhwald H, Sukhorukov G, Winterhalter M, Springer S. Controlled Intracellular Release of Peptides from Microcapsules Enhances Antigen Presentation on MHC Class I Molecules. Small. 2009;5:2168–2176. doi: 10.1002/smll.200900809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yuan J, Zhou S, You B, Wu L. Organic pigment particles coated with colloidal nano-silica particles via layer-by-layer assembly. Chem. Mater. 2005;17:3587–3594. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katsuhiko A, Qingmin J, Jonathan P. H. Enzyme-Encapsulated Layer-by-Layer Assemblies: Current Status and Challenges toward Ultimate Nanodevices. Adv. Polym. Sci. 2010;229:51–87. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pargaonkar N, Lvov Y, Li N, Steenekamp J, de Villiers M. Pharmaceutical Res. Controlled Release of Dexamethasone from Microcapsules Produced by Polyelectrolyte Layer-by-Layer Nanoassembly. 2005. pp. 826–835. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Agarwal A, Lvov Y, Sawant R, Torchilin V. Stable Nanocolloids of Poorly Soluble Drugs with High Drug Content Prepared Using Sonicated Layer-by-Layer Technology. J. Controlled Release. 2008;128:255–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lvov Y, Agarwal A, Sawant R, Torchilin V. Sonication Assisted Polyelectrolyte Nanoencapsulation of Paclitaxel and Tamoxifen. Pharma Focus Asia. 2008;7:36–40. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng Z, Zhang X, Carbo D, Clark C, Nathan C-A, Lvov Y. Sonication assisted synthesis of polyelectrolyte coated curcumin nanoparticles. Langmuir. 2010;26:7679–7681. doi: 10.1021/la101246a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teng X, Shchukin D, Möhwald H. Encapsulation of Water-Immiscible Solvents in Polyglutamate/ Polyelectrolyte Nanocontainers. Adv. Func. Mater. 2007;12:1273–1277. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Radtchenko I, Sukhorukov G, Möhwald H. A novel method for encapsulation of poorly water-soluble drugs: precipitation in polyelectrolyte multilayer shells. Intern. J. Pharmaceutics. 2002;242:219–223. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(02)00161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y, Yan Y, Cui J, Hosta-Rigau L, Heath J, Nice E, Caruso F. Encapsulation of Water-Insoluble Drugs in Polymer Capsules Prepared Using Mesoporous Silica Templates for Intracellular Drug Delivery. Advanced Materials. 2010:4293–4297. doi: 10.1002/adma.201001497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi X, Wang S, Chen X, Meshinchi S, Baker J. Encapsulation of Submicrometer-Sized 2-Methoxyestradiol Crystals into Polymer Multilayer Capsules for Biological Applications. Mol. Pharm. 2006;3:144–151. doi: 10.1021/mp050078s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suslick K. Sonochemistry. Science. 1990:247,1439–1445. doi: 10.1126/science.247.4949.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suslick K, Cline R, Jr., Hammerton D. The Sonochemical Hot Spot. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986;108:5641–5642. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suslick K, Flint E, Grinstaff M, Kemper K. Sonoluminescence from Metal Carbonyls. J. Phys. Chem. 1993;97:3098–3099. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borkent B, Gekle S, Prosperetti A, Lohse D. Nucleation threshold and deactivation mechanisms of nanoscopic cavitation nuclei. Phys. Fluids. 2009;21:102003. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dibbern E, Toublan F, Suslick K. Formation and Characterization of Polyglutamate Core−Shell Microspheres. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:6540–6541. doi: 10.1021/ja058198g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Belova V, Gorin D, Shchukin D, Möhwald H. Ultrasonic selective cavitation at patterned hydrophobic surfaces. Angewandte Chemie. 2010;122:7129–7134. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]