Abstract

Laser ablation of glass allows for production of microfluidic devices without the need of hydrofluoric acid and photolithography. The goal of this study was to compare the separation performance of microfluidic devices produced using a low-cost laser ablation system and conventional wet etching. During laser ablation, cracking of the glass substrate was prevented by heating the glass to 300°C. A range of laser energy densities was found to produce channel depths ranging from 4 – 35 μm and channel widths from 118 – 162 μm. The electroosmotic flow velocity was lower in laser-ablated devices, 0.110 ± 0.005 cm s−1, as compared to wet-etched microfluidic chips, 0.126 ± 0.003 cm s−1. Separations of both small and large molecules performed on both wet- and laser-ablated devices were compared by examining limits of detection, theoretical plate count, and peak asymmetry. Laser-induced fluorescence detection limits were 10 pM fluorescein for both types of devices. Laser-ablated and wet-etched microfluidic chips had reproducible migration times with ≤ 2.8% RSD and peak asymmetries ranging from 1.0 – 1.8. Numbers of theoretical plates were between 2.8- and 6.2-fold higher on the wet-etched devices compared to laser-ablated devices. Nevertheless, resolution between small and large analytes was accomplished, which indicates that laser ablation may find an application in pedagogical studies of electrophoresis or microfluidic devices, or in settings where hydrofluoric acid cannot be used.

Keywords: laser ablation, electrophoresis, microfluidic, separation

Introduction

Integrated microfluidic devices have frequently been employed in the study of macromolecules such as proteins [1–3], DNA [4–6], and RNA [7,8]. The popularity of these devices is owed, in part, to the versatility with which preparative and analytical steps can be integrated into single devices, affording highly automated and often high throughput analyses [9]. Developing such integrated systems often necessitates many revisions of device geometry, making rapid fabrication techniques desirable for the development of increasingly complex integrated systems.

A popular method for fabrication of polymeric microfluidic devices is rapid prototyping. In this process, a positive relief of the channels is produced by photolithography, and a liquid polymer, such as poly(dimethylsiloxane), is cast over the positive mold and allowed to cure [10]. Rapid prototyping is a powerful and versatile tool for the production of microfluidic devices and has been employed in the development of numerous novel and complex integrated systems [11–13]. Unfortunately, this method is not applicable to the production of glass microfluidic devices. Often, glass is a more desirable substrate as polymers often present limitations such as solvent incompatibility [14], small molecule permeability [15], and protein adsorption [16].

Traditionally, fabrication of glass microfluidic devices is accomplished by photolithography followed by wet chemical etching with hydrofluoric acid (HF) [17]. This process is considerably more time consuming than the rapid prototyping techniques employed in the production of polymeric devices (one day versus a few hours, respectively). In addition to the increased time involved in production of glass devices, the use of highly corrosive etchants such as HF poses significant safety and environmental hazards. New methods to produce glass microfluidic devices are required to reduce the cost, time, and safety hazards of conventional fabrication methods.

An alternative method to wet chemical etching is the use of laser ablation to produce the pattern of channels in either polymeric [18,19] or glass substrates [20–23]. This type of fabrication allows rapid production of microdevices without the use of hazardous chemical etchants or the need for high-resolution photomasks. And while complex and expensive high-speed laser systems [21–23] can be used, low-cost, commercially available laser engraving systems can also be utilized [20].

One aspect of these types of devices that has not been explored is the quality of separations obtained from these systems. Laser-ablated microfluidic channels have different surface topology from devices fabricated by traditional wet etching procedures, including a Gaussian-like cross sectional profile and greater surface roughness than their wet-etched counterparts. Furthermore, irregularities in channel depth and width along the length of the laser-ablated channels are evident. These differences in topology and irregularities of channel dimensions may affect the quality of electrophoretic separations, and therefore, may affect the usefulness of these devices.

In the present work, we have compared the performance of laser-ablated and wet-etched glass microfluidic devices. Performance was characterized by separations of small molecule fluorophores as well as fluorescently-labeled macromolecules. The primary figures of merit assessed were numbers of theoretical plates (N), migration times (tm), and peak asymmetries (As) for each analyte, as well as reproducibility of each of these parameters. Electroosmotic flow (EOF) velocity (vEOF) and limits of detection (LOD) for fluorescein were also determined. It was found that while the laser-ablated devices typically had lower numbers of theoretical plates, resolution of both small and macromolecules was still achieved. Laser-ablated devices should provide a fast, inexpensive, and safe alternative to wet-chemical etching of glass microfluidic devices and could be used in place of wet-etched devices for a number of applications.

Experimental

Reagents

HF was purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). HNO3 was purchased from EMD Chemicals, Inc. (Gibbstown, NJ). Rhodamine 6G was purchased from Eastman Chemical Co. (Kingsport, TN). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled insulin was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). FITC-labeled glucagon was purchased from Biomatik (Markham, ON).

All solutions were prepared in Mili-Q (Millipore, Bedford, MA) 18 MΩ ··cm deionized water. Unless stated otherwise, all other chemicals were from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Wet chemical etching

Glass microfluidic devices produced by conventional wet-etching were fabricated as described previously [24]. Briefly, borofloat glass coated with chrome and positive photoresist (Telic Co., Valencia, CA), was covered by a high resolution photomask representing the desired channel geometry and exposed with collimated UV radiation for 5 seconds. The exposed photoresist was removed with AZ 400K Developer (AZ Electronic Materials Corp., Sommerville, NJ), and the underlying chrome was removed using a chrome etchant solution (CR-7S, Cyantek Corp., Fremont, CA). Exposed glass was then etched to 35 μm depth with a 66:14:20 (v:v:v) mixture of H2O:HNO3:HF. Channel depths were verified using a P-15 stylus profilometer (KLA-Tencor, Milpitas, CA). Once etched, fluidic access holes were drilled and the remaining photoresist and chrome were removed. The etched substrates and borofloat cover slides were cleaned for 30 minutes in a 3:1 (v:v) solution of H2SO4:H2O2, followed by 30 minutes in a 5:1:1 (v:v:v) solution of H2O:NH4OH:H2O2. The cleaned substrates and cover slides were rinsed and bonded at 640°C for 8 hours.

Laser ablation

Production of laser-ablated microfluidic channels was performed using a commercial laser engraver (Epilog Zing 16, Epilog Laser, Golden, CO). A 127 mm x 127 mm x 1.1 mm thick piece of borofloat glass (Telic Co.) was heated to 300 ºC on a custom-built hot plate during etching to prevent cracking. PDF files of the microfluidic channels were sent to the engraver as a print job from a PC connected to the laser engraver. The PDF files were two-dimensional line drawings of the channel geometry with line weights of 0.001 inches. The laser frequency was 2500 Hz and ablated at a constant linear speed of 2.86 mm s−1, which was shown as 100% speed in the engraver software. Throughout the text, the use of linear energy density is used to compare various features of the etching process. Linear energy density (J mm−1) is the quotient of the laser power (J s−1) and linear speed (mm s−1) of the ablation process. For depth and width calibrations, laser power was varied, and the resulting etch depths and widths were measured by a profilometer (KLA-Tencor). Following ablation, the device was cooled to room temperature and removed from the engraver. Drilling of access holes and thermal bonding to another piece of glass were performed in the same manner as described for the wet-etched device.

Separations

Voltages for electrophoresis were generated using a programmable high voltage power supply (6AA12-P4, Ultravolt, Ronkonkoma, NY). Switching of high voltages was performed using a high voltage relay model G81A245 (Gigavac, Santa Barbara, CA). Voltage programming was achieved using control software written in LabView 8.5 (National Instruments, Austin, TX).

Separations were performed on microchips with cross-t geometries that had 1 cm channel lengths for sample, buffer and buffer waste channels, and a 4 cm separation channel. Gated injections were used, where during a separation, +1.25 kV was applied at both sample and buffer reservoirs while waste and separation reservoirs were grounded. To make an injection, a high voltage relay switched the voltage applied at the buffer reservoir to a floating voltage for 0.5 s. Separation occurred when the applied potential at the buffer reservoir was returned to +1.25 kV. All experiments were performed with a 20 mM tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris) buffer, pH 7.5. For evaluation of electrophoretic performance, all values are shown as the average ± 1 standard deviation. Intra-device reproducibility was evaluated by 5 repeat separations on each device, and inter-device reproducibility was evaluated across 3 devices of each type.

Imaging and Optical Detection

All microfluidic separations were performed on the stage of a Nikon Eclipse TS-100F inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY). For fluorescence imaging, epi-illumination was provided by a tungsten halogen lamp (model FOI 250, Techniquip, Pleasanton, CA). A filter cube (FITC-3540B, Semrock, Inc, Rochester, NY) contained an excitation band pass filter (488 ± 10 nm), emission bandpass filter (520 ± 10 nm), and a dichroic beam splitter which provided excitation light from the broadband light source to a 40X objective and filtered the fluorescence emission prior to detection. Fluorescence micrographs were acquired by a Cascade model EMCCD camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ). The camera was coupled to the microscope using a coupler with a 0.38X magnification lens (Optem SC38, Qioptiq LINOS, Inc. Fairport, NY).

For separation experiments and LOD determination, molecules were excited by the 488 nm line of a 50 mW solid-state laser (model 85-BCD-030-115, CVI Melles Griot, Albuquerque, NM). Fluorescence intensity was measured through a 40X objective lens (NA = 0.6) using a model D-104 photometer (Photon Technology International Inc., Birmingham, NJ) which allowed for the adjustment of a spatial filter to define the region of interest prior to detection by a model R1527 photomultiplier tube (Hamamatsu Corp., Bridgewater, NJ). Electropherograms were recorded using software written in Labview 8.5 interfaced to the PMT with a USB data acquisition device (model USB 6009, National Instruments, Austin, TX).

Limits of Detection

To determine the LOD, wet-etched and laser-ablated devices were loaded with buffer and voltage was applied for several minutes to acquire a baseline fluorescence signal. Once several minutes of baseline were collected, the voltage was stopped and buffer in the buffer reservoir was replaced with various concentrations of fluorescein in separation buffer (0, 10, 100, 250, 500, and 1000 pM). Application of the voltage resulted in an increase in the fluorescence signal and a calibration curve was constructed by plotting the average PMT signal as a function of fluorescein concentration. The LOD was defined as three times the standard deviation of the blank measurement divided by the slope of the calibration curve.

Determination of vEOF

The vEOF was determined using a current monitoring method described previously [25]. Briefly, each type of device was filled with 20 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.5, using a vacuum. Buffer in the sample reservoir was then replaced with 15 mM Tris buffer and +1.25 kV was applied at the sample reservoir and the separation reservoir was grounded. The filing time of the channel gave νEOF

Results and Discussion

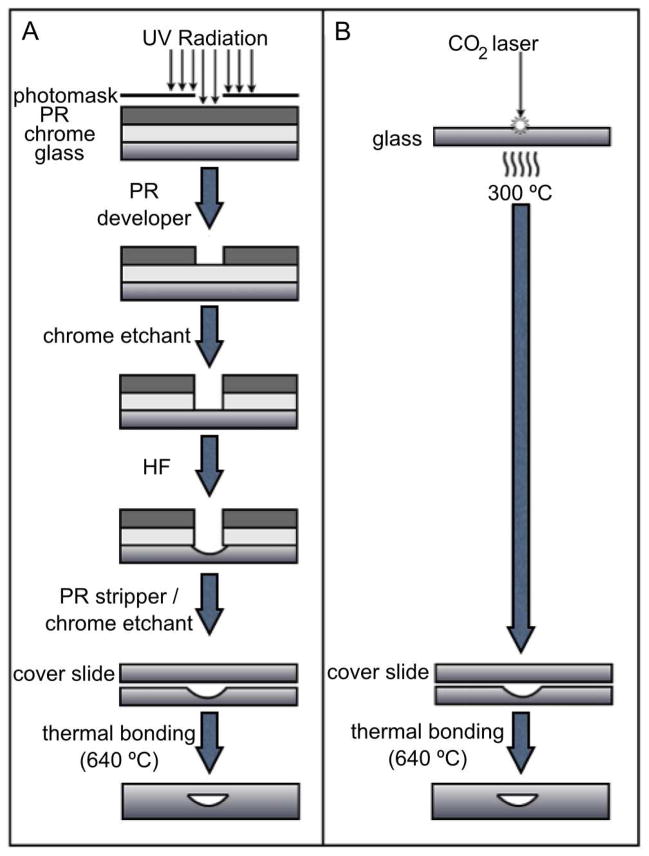

A comparison of wet etching and laser ablation procedures is illustrated in Figure 1. Fabrication of laser-ablated and wet-etched devices took approximately 12 and 17 hours, respectively, with the bulk of this time dedicated to the bonding of the top coverplate. Nevertheless, elimination of the photolithography step makes laser ablation a valuable approach to screening multiple revisions of device geometry without the need of purchasing numerous photomasks. Traditional photolithography and wet etching procedures involve a variety of solvents and chemical etchants all of which require special handling and disposal protocols to protect the user and the environment from hazardous exposure. Use of HF requires dedicated lab space, extensive use of personal protective equipment, and significant disposal costs. Due to these advantages of laser ablation over wet etching, if ablation is to become a viable tool for fabrication of microfluidic devices, the quality of separations obtained on these types of devices must be compared to separations achieved on comparable wet-etched devices.

Figure 1. Wet-etching and laser-ablation procedures.

A. Wet chemical etching follows a traditional workflow involving UV exposure, photoresist (PR) developing, chrome etching, glass etching with HF, stripping of the remaining PR and chrome and thermal bonding. B. Laser ablation of microfluidic channels is performed on uncoated glass substrates which are ready for thermal bonding following ablation.

Comparison of Wet-Etched and Laser-Ablated Channels

It was found that one of the challenges in producing laser-ablated microfluidic channels was that the ablation induced stresses within the substrate that led to fracturing of the glass device, sometimes hours after the etching procedure had completed. As shown previously, this problem could be avoided by heating the substrate to 300 ºC during laser ablation and allowing the device to cool slowly to room temperature [20].

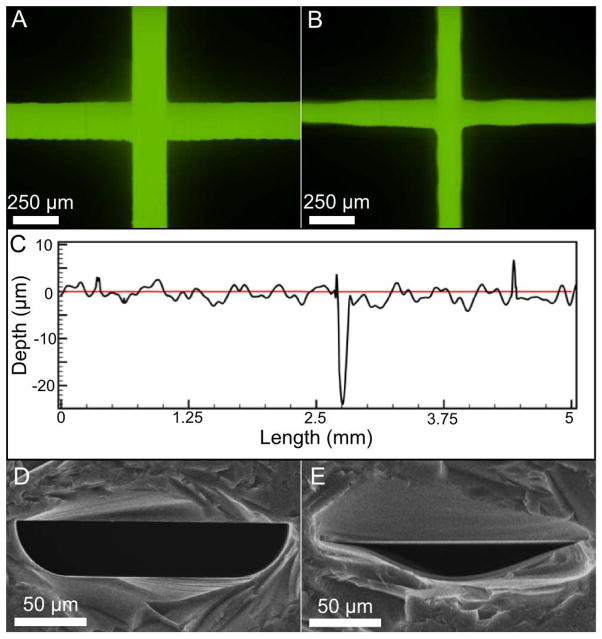

While more rapid and less hazardous than wet etching techniques, the quality and cross sectional geometry of the ablated channels differed from wet-etched channels. Figures 2A and 2B show fluorescence micrographs of the intersection of two channels in a wet-etched and laser-ablated device, respectively. The widths of the laser-ablated channels were less uniform than those of the wet-etched device. Although difficult to discern from these images, due to laser-ablation of each channel in the design, the depth at the intersection of the two channels in Figure 2B was approximately twice the depth of each channel.

Figure 2. Fluorescence and scanning electron micrographs.

A. Fluorescence micrograph of 100 μM fluorescein in wet-etched channels. The channel walls appear smooth and predominantly featureless. B. Fluorescence micrograph of 100 μM fluorescein in a representative laser-ablated device. Significant irregularities in channel width can be seen in both the horizontal and vertical channels. C. Surface profile along 5 mm lengths of laser-ablated (black) and wet etched channels (red). The 25 μm trench seen in the laser-ablated device occurs at the channel intersection where the glass was ablated twice. D. End-on SEM image showing the cross section of a wet-etched channel. The cross sectional geometry is the result of isotropic etching by HF. E. End-on SEM image of a laser-ablated channel detailing the Gaussian-like cross section.

Laser-ablation also produced irregularities in depth along the channel. A profilometer was used to measure 5 mm lengths within laser-ablated (black line) channels, shown in Figure 2C. The intersection of the two channels can be seen as the 25 μm trench 2.75 mm from the start of the profilometer trace. This increased depth was due to the double ablation as mentioned above. As can be seen, there was a significant roughness to the laser-ablated channels. This effect has been observed before [20], albeit with less roughness due to a lower linear energy density used previously in the ablation process.

This roughness was attributed to the step-wise motion of the motors driving the laser translation in the laser engraver. Using a profilometer, the standard deviation of the surface of an ablated channel was 1.28 μm with a maximum distance of ~12 μm between the highest and lowest points in a channel when the engraver was operated at a linear energy density of 1347 mJ mm−1. Also shown in Figure 2C is a profile taken from a 5 mm representative section of a wet-etched device (red line). The wet-etched channels were smoother than the laser-ablated channels with a standard deviation of 0.02 μm and a maximum distance of 0.14 μm. The roughness of the laser-ablated channel surface may affect the quality of electrophoretic separations achieved by introducing heterogeneous distribution of electric fields in these devices, or by inducing uneven flow paths through the separation channel.

Another difference between channels produced by these two methods was the dissimilarity in channel cross section. Figures 2D and E show SEM images of the cross section of devices fabricated by wet etching and laser-ablation, respectively. The well-known channel cross section of the wet-etched device is the result of isotropic etching of glass by HF. In contrast, laser ablation yielded microfluidic channels with Gaussian-like cross section. This Gaussian profile was the result of the profile of the laser incident on the substrate, with the greatest laser intensity at the center of the laser focus. While these differences in surface quality and channel cross section have been described previously [20], there has been no evaluation of the differences in separation performance between these types of devices.

Calibration of etch depths and widths

Figure 3 shows depths and widths of channels achieved as a function of linear energy density. Etch depths had a linear response with linear energy density to a limit of 36 ± 4 μm. At higher linear energy densities, deeper channels were produced, but significant cracking of the substrate occurred. Multiple etchings along the same channel at low linear energy densities increased the depth of the channel without cracking. However, since the range of achievable channel depths during one pass of the laser was appropriate for zone electrophoresis, no systematic characterization of the largest depth that could be produced by multiple passes of the laser was made. Channel width also varied as a function of linear energy density; however at linear energy densities above 980 mJ mm−1, the channel width remained constant (162 ± 8 μm). As reported elsewhere [20], this plateau of the achievable width was due to the distribution of the laser energy in the laser spot. At the lowest energy density, the center of the laser spot ablated the glass. Increasing the energy density increased the proportion of the laser spot that was used to ablate the glass. At 980 mJ mm−1, the entire laser spot ablated the glass, so increasing the linear energy density above this value did not increase the width of the channels.

Figure 3. Affect of linear energy density on channel depth and width.

Channel depth (circles) was linear as a function of linear energy density, whereas channel width (squares) reached a maximum of 162 ± 8 μm at 980 mJ mm−1.

Another aspect of the ablation to be controlled was the formation of a raised rim at the outside edge of the channel. The formation of this raised region was a result of the ablated glass redepositing on the surface of the device and was absent in the wet-etched channels. Larger rims were formed at higher linear energy densities, and rims > 1 μm inhibited bonding of the coverplate. All linear energy densities shown in Figure 3 produced rim heights ≤ 1 μm.

Limits of detection and νEOF

The LOD was determined using fluorescein as the analyte and was not found by injecting different concentrations of fluorescein into the separation channel. The difference in resistances of the separation channels between wet-etched and laser-ablated devices and the differences in etch depths at the intersection of the injection cross would affect the amount of fluorescein injected by a gated injection, and therefore, the LOD determination. Calibrations of fluorescein were performed as described in the Experimental section and found to be y = 0.00081x – 0.009, r2 = 0.992, and y = 0.00074x + 0.035, r2 = 0.961 for laser-ablated and wet-etched devices, respectively. The LOD of fluorescein was 10 pM for both laser-ablated and wet-etched devices.

The νEOF was determined for the buffer system used in the separations detailed below. It was found that the laser-ablated devices (0.110 ± 0.005 cm s−1) had slightly lower vEOF than the wet-etched devices (0.126 ± 0.003 cm s−1). Although not largely different, these differences in vEOF could account for the longer migration times for all analytes examined in the laser-ablated devices (see below). The reason for the decreased vEOF is unclear at the moment, although it may be due to the surface roughness of the devices or the different cross sections of the two types of channels.

Zone electrophoresis

To compare separation performance of laser-ablated and wet-etched microfluidic devices, separations of small molecules (fluorescein and rhodamine 6G) and larger, fluorescently-labeled macromolecules of peptides (FITC-labeled glucagon and insulin) were carried out on devices etched to 35 μm depth. Analyte peaks were evaluated for number of theoretical plates (N), migration times (tm) and peak asymmetries (As). Figure 4 shows representative electropherograms obtained on wet- and laser-ablated devices, and Table 1 summarizes the figures of merit for all analytes. The results summarized in Table 1 are specific to the data shown in Figure 4, which represents 5 separations on a single device. Device-to-device reproducibility was evaluated using three laser-ablated and three wet-etched microfluidic chips and resulted in inter-device RSDs ≤ 20% for all values except number of theoretical plates. In the case of theoretical plates, inter-device RSDs were 50 ± 5% for wet etched devices and 61 ± 12% for laser etched devices, averaged across all analytes.

Figure 4. Electrophoretic separations performed on wet-etched and laser-ablated devices.

A. Electropherogram of 25 nM each rhodamine 6G (i and ii), FITC-glucagon (iii), FITC-insulin (iv) and fluorescein (v) performed on a wet-etched device. B. The same analytes were separated on a laser-ablated device (peak identities same as above). Separation buffer was 20 mM Tris pH 7.5 and separation voltage was +1.25 kV.

Table 1.

Figures of merit for separations

| Wet-Etched Device |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tm (s) | RSD (%) | As | RSD (%) | Peak Area (V s) | RSD (%) | N | RSD (%) | |

| Rhodamine | 21.6 | 1.0 | 1.5 * | 12.9 | 0.57 | 22.3 | 9550 | 7.2 |

| Glucagon | 33.7 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 3.8 | 1.96 | 3.8 | 5530 | 4.5 |

| Insulin | 40.0 | 1.6 | 1.2 * | 10.6 | 0.63 | 4.5 | 3560 | 5.5 |

| Fluorescein | 52.7 | 2.7 | 1.1 * | 4.4 | 5.88 | 5.6 | 7400 | 3.3 |

| Laser-Ablated Device |

||||||||

| Rhodamine | 27.7 | 0.4 | 1.8 * | 11.2 | 1.00 | 4.6 | 1530 | 6.4 |

| Glucagon | 44.5 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 9.2 | 3.20 | 12.2 | 1980 | 4.1 |

| Insulin | 54.7 | 0.6 | 1.2 * | 9.2 | 1.30 | 10.5 | 1120 | 7.8 |

| Fluorescein | 82.8 | 0.9 | 1.1 * | 3.5 | 7.50 | 8.6 | 2530 | 7.4 |

no statistical difference (p > 0.05)

In general, separations of both small and large molecules were comparable on both devices. Most figures of merit were significantly different (p < 0.05) between the two devices, except for asymmetry values. Although slightly longer migration times were observed for all analytes in the laser-ablated devices, migration time reproducibilities were ≤ 2.8% for all analytes on each type of device. The longer migration times in the laser-ablated devices were attributed, in part, to the lower vEOF found in these devices compared to the wet-etched devices.

The largest difference between the separations was the lower number of theoretical plates in the laser-ablated microfluidic chip. Wet-etched devices produced efficiencies that were between 2.8- and 6.2-fold higher than laser-ablated devices. Although a systematic characterization of the band-broadening mechanism was beyond the scope of this work, there are several possibilities for the decreased efficiencies observed in the laser-ablated device. As the migration times were longer in the laser-ablated device, the amount of longitudinal diffusion would have increased compared to the wet-etched microfluidic chip. However, as the decreased peak efficiencies found on the laser-ablated devices were not proportional to the decreased EOF velocities, the total broadening may not only be a matter of increased diffusional band broadening. There is a possibility that the ablation process created a favorable binding surface toward some of the analytes, via either increased surface area of the channels or a change in surface chemistry of the glass walls. Also, it is likely that there were differences in the injection volumes of the two devices as described above. A larger injection plug length would lead to decreased number of theoretical plates. In addition to these mechanisms, peak broadening may have occurred if there were flow-irregularities in the laser-etched device due to the irregular channel widths and depths. More work will be needed to describe the contributions from these various effects.

Despite these disparities in peak efficiency, laser-ablated devices resolved all peaks investigated. It may be possible to increase the peak efficiency by reducing the linear energy density in the region of the channel intersection, which would reduce the depth of the double-ablated region. Also, further characterization of the effect of the channel roughness on the separation efficiency could be undertaken. It may be more ideal to make more passes with the laser ablation system at lower linear energy densities to try and reduce the roughness of the channels.

Conclusions

Laser ablation allows a rapid and flexible method to fabricate glass microfluidic devices without the hazards associated with wet chemical etching. This work has shown separations achieved on devices made with a low-cost, commercially available laser engraving system were not as efficient as those achieved on wet-etched glass devices. We believe that the benefit of not working with HF and photolithography may outweigh the disadvantages of increased peak broadening observed in some cases. In addition to these benefits of laser-ablated microfluidic devices, this method may present a novel pedagogical opportunity as an introduction to both electrophoresis and microfluidic systems owing to the low cost and commercial availability of the laser engraver system. In addition, a range of devices could conceivably be made with this fabrication procedure for performing non-electrophoretic separations, such as T-immunoassays [26], solid phase extraction [27], or investigation of reaction kinetics [28].

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01 DK080714). We would like to thank the faculty and staff of the Florida State University FormLab for their work in administering the laser etching facilities. We would also like to thank Dr. Eric Lochner in the Department of Physics at Florida State University for acquiring the SEM images.

References

- 1.Sanders GHW, Manz A. TRAC-Trend Anal Chem. 2000;19:364–378. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao J, Xu JD, Locascio LE, Lee CS. Anal Chem. 2001;73:2648–2655. doi: 10.1021/ac001126h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luk VN, Wheeler AR. Anal Chem. 2009;81:4524–4530. doi: 10.1021/ac900522a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foquet M, Korlach J, Zipfel W, Webb WW, Craighead HG. Anal Chem. 2002;74:1415–1422. doi: 10.1021/ac011076w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kopp MU, de Mello AJ, Manz A. Science. 1998;280:1046–1048. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5366.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hua ZS, Rouse JL, Eckhardt AE, Srinivasan V, Pamula VK, Schell WA, Benton JL, Mitchell TG, Pollack MG. Anal Chem. 2010;82:2310–2316. doi: 10.1021/ac902510u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meloon B, Gamliel N, Sevignani C, Ferracin M, Dumitru CD, Shimizu M, Zupo S, Dono M, Alder H, Bullrich F, Negrini M, Croce CM. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9740–9744. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403293101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marcus JS, Anderson WF, Quake SR. Anal Chem. 2006;78:956–958. doi: 10.1021/ac0513865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okagbare PI, Soper SA. Analyst. 2009;134:97–106. doi: 10.1039/b816383a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duffy DC, McDonald C, Schueller OJA, Whitesides GM. Anal Chem. 1998;70:4974–4984. doi: 10.1021/ac980656z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen D, Du WB, Liu Y, Liu WS, Kuznetsov A, Mendez FE, Philipson LH, Ismagilov RF. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:16843–16848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807916105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quake SR, Sherer A. Science. 2000;290:1536–1540. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5496.1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thorsen T, Maerkl SJ, Quake SR. Science. 2002;298:580–584. doi: 10.1126/science.1076996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JN, Park C, Whitesides GM. Anal Chem. 2003;75:6544–6554. doi: 10.1021/ac0346712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roman GT, McDaniel K, Culbertson CT. Analyst. 2006;131:194–201. doi: 10.1039/b510765b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Makamba H, Kim JH, Lim K, Park N, Hahn JH. Electrophoresis. 2003;24:3607–3619. doi: 10.1002/elps.200305627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrison DJ, Fluri K, Seiler K, Fan Z, Effenhauser CS, Manz A. Science. 1993;261:895–897. doi: 10.1126/science.261.5123.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klank H, Kutter JP, Geschke O. Lab Chip. 2002;2:242–246. doi: 10.1039/b206409j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pugmire DL, Waddell EA, Haasch R, Tarlov MJ, Locascio LE. Anal Chem. 2002;74:871–878. doi: 10.1021/ac011026r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yen MH, Cheng JY, Wei CW, Chuang YC, Young TH. J Micromech Microeng. 2006;16:1143–1153. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaffer CB, Brodeur A, Garcia JF, Mazur E. Opt Lett. 2001;26:93–95. doi: 10.1364/ol.26.000093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y, Itoh K, Watanabe W, Yamada K, Kuroda D, Nishii J, Jiang Y. Opt Lett. 2001;26:1912–1914. doi: 10.1364/ol.26.001912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugioka K, Hanada Y, Midorikawa K. Laser Photonics Rev. 2010;4:386–400. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baker CA, Roper MG. J Chrom A. 2010;1217:4743–4748. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2010.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang XH, Gordon MJ, Zare RN. Anal Chem. 1988;60:1837–1838. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hatch A, Kamholz AE, Hawkins KR, Munson MS, Schilling EA, Weigl BH, Yager P. Nature Biotech. 2001;19:461–465. doi: 10.1038/88135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Breadmore MC, Wolfe KA, Arcibal IG, Leung WK, Dickson D, Giordano BC, Power ME, Ferrance JP, Feldman SH, Norris PM, Landers JP. Anal Chem. 2003;75:1880–1886. doi: 10.1021/ac0204855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song H, Ismagilov RF. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:14613–14619. doi: 10.1021/ja0354566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]