Abstract

Objective

Previous research has found an association between sleep problems and suicidal behavior. However, it is still unclear whether the association can be largely explained by depression. In this study, we prospectively examined relationships between sleep problems when participants were 12–14 years old and subsequent suicidal thoughts and self-harm behaviors —including suicide attempts— at ages 15–17 while controlling for depressive symptoms at baseline.

Methods

Study participants were 280 boys and 112 girls from a community sample of high-risk alcoholic families and controls in an ongoing longitudinal study.

Results

Controlling for gender, parental alcoholism and parental suicidal thoughts, and prior suicidal thoughts or self-harm behaviors when participants were 12–14 years old, having trouble sleeping at 12–14 significantly predicted suicidal thoughts and self-harm behaviors at ages 15–17. Depressive symptoms, nightmares, aggressive behavior, and substance-related problems at ages 12–14 were not significant predictors when other variables were in the model.

Conclusions

Having trouble sleeping was a strong predictor of subsequent suicidal thoughts and self-harm behaviors in adolescence. Sleep problems may be an early and important marker for suicidal behavior in adolescence. Parents and primary care physicians are encouraged to be vigilant and screen for, sleep problems in young adolescents. Future research should determine if early intervention with sleep disturbances reduces the risk for suicidality in adolescents.

Keywords: sleep disturbance, suicidal thoughts, suicide attempts, self-harm behaviors, adolescence

1. Introduction

In 2002, the Institute of Medicine report on Reducing Suicide recommended that prospective studies of populations at high risk for the onset of suicidal behavior were needed (Goldsmith et al., 2002). Of particular concern are adolescents, because suicide is the third leading cause of death in the 15–24 year-old age group (Cash and Bridge, 2009). Although the Institute of Medicine report did not mention sleep disturbances as a risk factor for suicidality, a consistent and strong association between sleep disturbances and suicidality has been reported in both adults (Agargun et al., 2007; Chellappa and Araujo, 2007; McGirr et al., 2007; Sjostrom et al., 2007; Turvey et al., 2002; Wallander et al., 2007; Wojnar et al., 2009) and adolescents (Bailly et al., 2004; Barbe et al., 2005; Choquet et al., 1993; Choquet and Menke, 1990; Goldstein et al., 2008; Liu, 2004; Nrugham et al., 2008).

Among adolescents, insomnia has been linked to suicidal thoughts (Bailly et al., 2004; Barbe et al., 2005; Choquet and Menke, 1990), attempts (Bailly et al., 2004; Nrugham et al., 2008), and completed suicides (Goldstein et al., 2008). Similarly, nightmares have been linked to both suicidal thoughts (Choquet and Menke, 1990; Liu, 2004) and suicide attempts (Liu, 2004). These relationships have been reported in both general student populations (Liu, 2004; Nrugham et al., 2008) and clinical samples (Barbe et al., 2005). With one exception (Nrugham et al., 2008), however, most of these studies were cross-sectional in design. In the one prospective study already present in the literature, Nrugham et al. (2008), followed 265 students in Norway for 5 years, starting when they were approximately 15 years of age. Bivariate analyses demonstrated that insomnia at age 15 predicted suicide attempts during the next 5 years. In multivariate analyses that controlled for depressive symptoms, however, insomnia was no longer predictive. This is probably due to the well-established association between depression and suicide attempts in adolescents (Kovacs et al., 1993; Lewinsohn et al., 1994; Liu and Buysse, 2006). The results of this study illustrate the importance of controlling for depressive symptoms. Nevertheless, the authors cautioned that a 70% follow-up rate and a small number of boys (N=61) in the sample may have biased the results. More prospective studies are clearly needed to address the possible relationships between sleep problems and suicidal behavior.

Children of alcoholics (COAs) are another high-risk group for numerous adverse outcomes including substance use disorders, internalizing disorders, and externalizing disorders — all of which can increase the risk for suicidality (Lieberman, 2000; Zucker et al., 2008). Recent work also suggests that COAs may differ from other children by objectively measured sleep disturbance (Dahl et al., 2003; Tarokh and Carskadon, 2009). Therefore, the relationship between sleep disturbances and suicidality in COAs warrants study.

Here, we report to our knowledge the first prospective study of high-risk adolescents to investigate a potential link between sleep disturbances and subsequent suicidal thoughts and either self-harm behaviors or suicide attempts (self-harm/suicidal behaviors). We hypothesized that (1) COAs would have higher rates of sleep disturbance than non-COAs; (2) COAs would have higher rates of suicidal thoughts and self-harm/suicidal behaviors than non-COAs; and (3) sleep disturbances would prospectively predict the development of suicidal thoughts and self-harm/suicidal behaviors after controlling for depressive symptoms, COA status, and other potentially confounding variables. We used the terms “sleep disturbances”, “poor sleep”, “insomnia”, and “sleep problems” interchangeably in this paper.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

The present study is part of the Michigan Longitudinal Study, an ongoing longitudinal family study on the development of risk for alcohol and other substance use disorders (Zucker and Fitzgerald, 1991; Zucker et al., 2000). The larger study recruited a population-based sample of alcoholic men, their partners (whose substance use disorder was free to vary), and controls, as well as their initially 3–5-year-old sons (N = 311 families). The 3–11-year-old daughters in the families were also invited to participate after the study began. The majority of these girls joined the project between ages 6 to 11.

Alcoholic men were identified by population sampling methods involving (a) a canvass of all courts in a four-county-wide area for drunk drivers with high blood alcohol levels (BAL > 0.15%); and (b) a neighborhood canvass in the areas where the court-selected alcoholics lived to recruit additional alcoholics. The neighborhood canvass also recruited a control group of children and their families who resided in the same neighborhood as the alcoholic families, but whose parents had no lifetime history of substance abuse/dependence. Male offspring of control families were age-matched to the male child in the alcoholic family residing in the same neighborhood. Both biological parents were required to be living together in the same household (either as married couples or domestic partners) and to have a 3–5 year-old son living with them at the time of recruitment. Presence of fetal alcohol syndrome was an exclusionary criterion.

The current sample consists of longitudinal data from 280 boys and 112 girls. All adolescents provided data on suicidal behavior when they were 12–14 years old (Time 4) and 15–17 years old (Time 5). Seventy-five percent (75%) of participants had at least one parent who met a lifetime alcohol use disorder (AUD) diagnosis when they first took part in the study (i.e., 3–5 years old for most participants, 6–11 years old for some participants, as most girls joined the study at that age) and 25% of participants were controls with non-AUD parents.

All families were Caucasian-Americans. Less than 4 percent of the population in the study sampling area that met inclusion criteria was non-Caucasian. Given the study’s sample size, if non-Caucasian ethnic/racial groups were included, the number available would not have permitted any effective analysis to be done. As there is an extensive literature showing a relationship between substance abuse and ethnic/racial status (Hasin et al., 2007; Kessler et al., 2005), including such variation in the study without being able to statistically model its effects would only contribute to error. Therefore, investigators originally opted to exclude this variation. The study thereafter has recruited an additional sample of both African-American and Hispanic families using parallel recruitment criteria; however, offspring from these families are largely preadolescent and thus do not provide the endpoint data necessary for this study.

2.2 Procedures

Trained interviewers who were blind to family diagnostic status collected the data. The contact time for each family varied, depending on the data collection wave. Typically, each parent was involved for 9–10 hours and each child for seven hours spread over seven sessions. A variety of age-appropriate tasks (e.g., questionnaires, semi-structured interviews, and interactive tasks) were administered, and most of the contacts occurred in the families’ homes. Special arrangement was made to collect data from families who had relocated. No families were lost due to relocation.

Participants and their parents were interviewed at three-year intervals. Participants were 3–5 years old at Time 1, 6–8 years old at Time 2, 9–11 years old at Time 3, 12–14 years old at Time 4 and 15–17 years old at Time 5. The data presented in this paper were collected at Times 4 and 5, except for parental measures, which was diagnosed at Time 1 or when the participants first joined the study (some participants joined the study at ages 6–11).

When information about suicidal ideation or attempt was discovered, interviewers reported the information immediately to senior clinicians of the study. The clinicians assessed the circumstances and made a decision on whether any further action needed to be taken. If the risk for suicidal behavior was significant, our research staff would ask the participants for permission to inform their parents about the situation and provide referral information to the family. Moreover, a follow-up contact would be conducted to make sure that the family had pursued the referral and that the suicidal risk of the participants was no longer an issue.

2.3 Instruments and Measures

Adolescent measures

The Youth Self Report questionnaire (YSR; Achenbach, 1991) was used to collect data about sleep disturbances, suicidal thoughts and self-harm behavior, depressive symptoms, and aggressive behavior. The YSR is a widely used self-report instrument measuring childhood behavioral problems, keyed to the past six months. Responses are given on a three-point scale (0 = not true; 1 = somewhat or sometimes true; 2 = very true or often true). It was administered at two time points, once when participants were between 12 and 14 years old (Time 4), and again when participants were between 15 and 17 years old (Time 5).

Two YSR items were used to measure suicidal thoughts and either self-harm or suicidal behavior at both Times 4 and 5. Specifically, suicidal thoughts were measured by the item —I think about killing myself. Self-harm behavior, including suicide attempts, was measured by the item —I deliberately try to harm or kill myself. Similar to the sleep items, responses were recoded as dichotomous variables (0 = not true, 1 = sometimes or often true), as less than 1% of the sample scored a —2 on these items at Time 4 (thoughts about killing oneself: .8%; self-harm/suicidal behavior: .8%) and Time 5 (thoughts about killing oneself: .8%; self-harm/suicidal behavior: .5%).

Three YSR items were selected to indicate sleep problems when participants were 12–14 years old: having trouble sleeping, having nightmares, and overtiredness. Having trouble sleeping was employed as the measure for insomnia. Overtiredness was selected because one previous study reported a relationship between tiredness and suicidal thoughts in adolescents (Choquet et al., 1993). Responses were recoded as dichotomous variables (0 = not true, 1 = sometimes or often true), because a relatively small percentage of the sample scored a —2 on these items (e.g., trouble sleeping: 6%; overtiredness: 8.6 %; nightmares: 3.8%). Adolescents who reported having problems sleeping were also more likely to report feeling overtired (χ2 (1) = 21.199, p < .001) or having nightmares (χ2 (1) = 9.572, p < .01). However, self-reported nightmares were not correlated with overtiredness (χ2 (1) =.685, p = .408).

Depressive symptoms were measured by the Depression subscale of the YSR (Clarke et al., 1992) when participants were 12–14 years old. The original subscale consists of 15 items from YSR – “can’t concentrate, can’t pay attention,” “cries a lot,” “deliberately hurt or kill myself”, “doesn’t eat well,” “feel worthless or inferior,” “feels too guilty,” “overtired”, “sleeps less than most children,” “sleep more than most children,” “think about killing oneself,” “trouble sleeping,” “underactive, slow moving, lacks energy,” “unhappy, sad, or depressed,” “withdrawn, uninvolved with others,” and worrying “. To prevent spurious correlations with the main predictor and outcome variables, the four sleep items (i.e., “overtired,” “sleeps less than most children,” “sleep more than most children”) and the two items regarding suicidality (i.e., “deliberately try to hurt or kill myself,” “think about killing myself”) were omitted before calculating the subscale scores. Internal consistency (Cronbach alpha) of the scale based on the remaining 9 items was .69.

Aggressive behaviors at ages 12–14 was measured the 18-item Aggressive Behavior subscale. Responses were summed to calculate an aggressive behavior score, with higher scores indicating more aggressive behavior. The internal consistency (Cronbach alpha) of the scale was .69.

Alcohol- and drug-related problems at ages 12–14 were assessed by the Drinking and other Drug Use History Questionnaire Youth Version (DDHQ-Y; Zucker and Fitzgerald, 2002). Participants indicated whether they had any of 31 problems related to their substance use (e.g., missing school, getting into trouble with parents, driving under the influence of alcohol or drugs). Problems were listed separately for drinking and illicit drug use. A dichotomous composite variable was formed based on all the items -- a response of “0” indicated an absence of alcohol- or drug-related problems on any item and a response of “1” indicated the presence of a problem with either alcohol or drugs.

Parent measures

A lifetime parental diagnosis of alcohol use disorder (AUD) when the participants first joined the study (most participants joined the study at ages 3–5 years old) was assessed by three instruments: the Short Michigan Alcohol Screening Test (Selzer et al., 1975), the Diagnostic Interview Schedule Version III (Robins et al., 1980), and the Drinking and Drug History Questionnaire (Zucker et al., 1990). Based on information collected by these instruments, a trained clinician made these diagnoses using DSM-IV criteria. The availability of three sources of information collected over three different sessions, separated sometimes by as much as several months, served as an across-method validity check on respondent replies. In cases of discrepant information, the data represented by the majority of information sources were used in establishing the diagnosis. Inter-rater reliability for the diagnosis was excellent (kappa = 0.81). Children were coded as having an alcoholic father or mother if the parent met lifetime criteria for AUD when they first participated in the study. Seventy-one percent of participants had an alcoholic father and 30% of participants had an alcoholic mother.

Parental suicidality when the child first participated in the study was assessed by the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck et al., 1988; Beck et al., 1961) and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD; Hamilton, 1960; Hamilton, 1969). Both instruments include questions about suicidal thoughts and attempts. The BDI is a widely used self-report measure of depression and has been validated in numerous studies (Beck et al., 1988; Carroll et al., 1973). This 13-item instrument assesses cognitive, emotional, motivational, and physical manifestations of depression. For each item in the BDI, parents were asked to select a statement that best described the way they felt in the past two weeks. The HRSD is a well-established instrument that collects clinician ratings of depression. In this study, trained researcher associates interviewed the parents of study participants and then completed the HRSD. Two set of ratings were made, one based on current depressive symptoms and the other based on “worse ever” depressive symptoms, i.e., when the individuals were most depressed in their lives. Using these measures, 27% of fathers and 28.1% of mothers had either considered or attempted suicide.

2.4 Analytic plan

After generating descriptive statistics, chi square tests were used to the test the first two hypotheses that COAs would have higher frequencies of (1) sleep disturbances and (2) suicidal thoughts and self-harm/suicidal behaviors than non-COAs. Logistic regression models were used to analyze data predicting the two outcome variables: suicidal thoughts and self-harm/suicidal behaviors, respectively, when participants were 15–17 years old. The three categories of sleep problems (trouble sleeping, nightmares, and overtiredness) were the predictors of primary interest. Other predictor variables which were measured when participants were 12–14 years old included previous suicidal thoughts or self-harm/suicidal behaviors, depressive symptoms, aggressive behaviors, and substance-related problems. Additionally, parental alcoholism and history of suicidal thoughts as well as the gender and age of the adolescent participants were used in the analyses as statistical controls.

For each outcome variable, we conducted two sets of analyses. First, a direct logistic regression model was estimated. In this model, all predictors were entered into the equation simultaneously as a single block. No assumption was made regarding the relative importance of the predictors. Each predictor was evaluated based on the unique contribution it made in predicting the outcome variable. Second, a sequential logistic regression model was estimated. In this model, blocks of predictors were entered into the equation sequentially based on their theoretical importance. In block 1, we entered suicidal thoughts or behaviors at ages 12–14, and two demographic variables (gender and age). In block 2, we entered parental alcoholism and suicidal ideation or thoughts. And finally in block 3, we entered predictors from ages 12–14, including depressive symptoms, aggressive behavior, alcohol or drug use related problems, and the three sleep variables into the equation.

2.5 Ethics

The study was approved by the Institution Review Board of the University of Michigan Health System. Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study.

3. Results

3.1 Descriptive statistics

At ages 15–17, 7.6% reported having suicidal thoughts and 5% reported that they had tried to harm or kill themselves in the last six months. The figures were similar when participants were at ages 12–14 at which time 4.1% had suicidal thoughts and 3.3% had actually engaged in self-harm/suicidal behavior. There was no completed suicide at either wave. However, there was one complete suicide when participants were 18–20 years old. Regarding sleep disturbances at ages 12–14, over one-quarter of participants (27.5%) reported trouble sleeping and more than one-third endorsed feeling overtired (35.3%) or having nightmares (40.8%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics on all variables ( N=392)

| % Yes | Mean | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicidal thoughts at ages 12–14 | 4.1% | - | - | 0 (no) -1 (yes) |

| Suicidal thoughts at ages 15–17 | 7.6% | - | - | 0 (no) -1 (yes) |

| Self-harm/suicidal behavior at ages 12–14 | 3.3% | - | - | 0 (no) -1 (yes) |

| Self-harm/suicidal behavior at ages 15–17 | 5.0% | - | - | 0 (no) -1 (yes) |

| Sleep problems at ages 12–14 | ||||

| Trouble sleeping | 27.5% | - | - | 0 (no) -1 (yes) |

| Overtired | 35.3% | - | - | 0 (no) -1 (yes) |

| Nightmares | 40.8% | - | - | 0 (no) -1 (yes) |

| Depressive symptoms at ages 12–14 (excluding sleep problems and suicidal behavior) | - | 0.31 | 0.27 | |

| Aggressive behavior at ages 12–14 | - | 7.93 | 5.31 | |

| Presence of alcohol or drug related problems | 9.4% | - | - | 0 (no) -1 (yes) |

| Gender | 71.4 % male | - | - | 0 (female) -1 (male) |

| Age at Time 5 | - | 16.53 | 0.93 | 14.72 - 18.84a |

| Paternal alcoholism | 71.7% alcoholic | - | - | 0 (no) -1 (yes) |

| Maternal alcoholism | 29.6% alcoholic | - | - | 0 (no) -1 (yes) |

| Paternal suicidal ideation or attempts | 27.0% | - | - | 0 (no) -1 (yes) |

| Maternal suicidal ideation or attempts | 28.1% | - | - | 0 (no) -1 (yes) |

Note.

In this paper, we analyzed the data from the Michigan Longitudinal Study at Time 4 (12–14 years old) and Time 5 (15–17 years old). Due to delay in scheduling, about 5% of the participants were 18 years old at Time 5.

A higher percentage of girls (11.4%) than boys (5.1%) reported having suicidal thoughts at 12–14 years old (χ2 (1) = 4.62, p < .05). There were no gender differences in suicidal thoughts at 15–17 years old (girls: 7.9%; boys: 7.4%;χ2 (1) = .03, p = .87). Similarly, no gender differences in self-harm/suicidal behaviors were found at either age period (ages 12–14: girls: 2.6%; boys: 3.5%;χ 2 (1) = .21, p = .65 ; ages 15–17: girls: 5.3%; boys: 4.9%;χ2 (1) = .02, p = .90). A larger percentage of girls (43%) reported being overtired than boys (32.2%) at ages 12–14 (χ2 (1) = 4.17, p <.05). There were no gender differences for having nightmares (girls: 48.2%; boys: 37.82%;χ2 (1) = 3.66, p =.06) or trouble sleeping (girls: 28,1%; boys: 27.2%;χ 2 (1) =.03, p =.86).

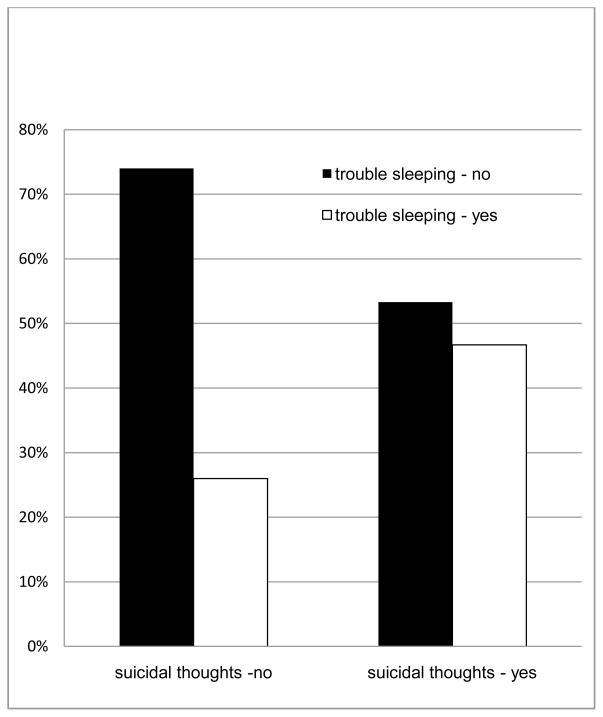

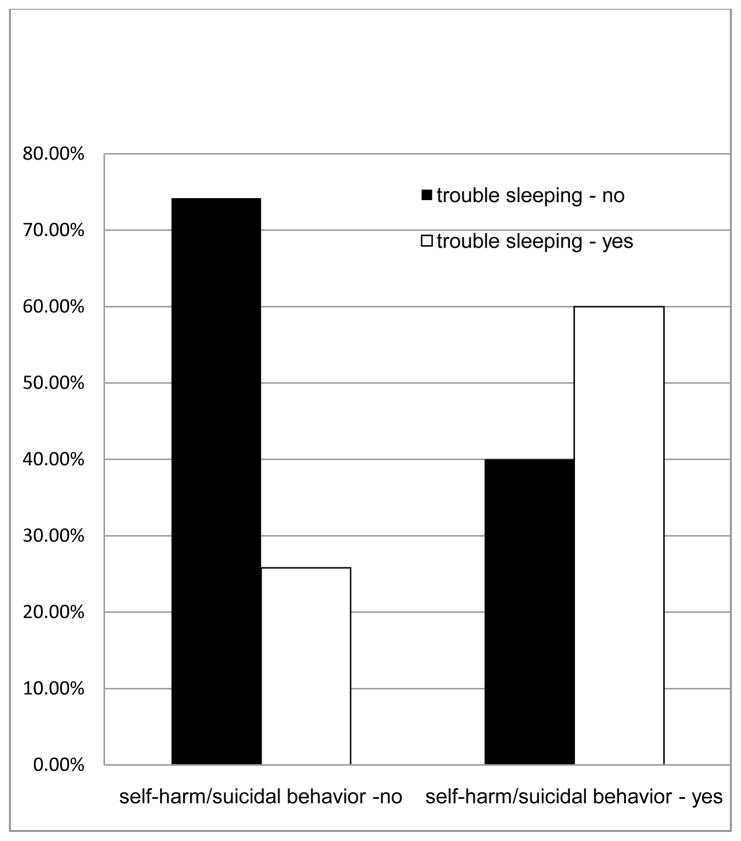

There was a significant relationship between having trouble sleeping at ages 12–14 and suicidal thoughts at ages 15–17 (χ2 (1) = 5.95, p < .05, Figure 1). Among adolescents who had no suicidal thoughts at ages 15–17, 26% had trouble sleeping at ages 12–14. However, among adolescents who had suicidal thoughts at ages 15–17, almost half (46.7%) had trouble sleeping at an earlier age. There was also a significant relationship between having trouble sleeping at ages 12–14 and self-harm/suicidal attempts at ages 15–17 (χ2 (1) = 11.12, p = .001, Figure 2). About a quarter (25.8%) of 15–17-year-old adolescents who did not engage in self-harm or suicidal behavior had trouble sleeping at ages 12–14. In contrast, 60% of adolescents who engage in self-harm or suicidal behavior had trouble sleeping. There were no significant associations between the two other sleep variables (having nightmares and overtiredness) and suicidal thoughts (nightmares:χ2 (1) = 1.43, p = .23; overtiredness: χ2 (1) = .88, p =.35) or self-harm/suicidal behavior (nightmares:χ2 (1) = .00, p = .98; overtiredness: χ2 (1) = .84, p =.36).

Figure 1. Relationship between having trouble sleeping at ages 12–14 and suicidal thoughts at ages 15–17.

Note. The association between “having trouble sleeping” and suicidal thoughts was statistically significant (χ2 (1) = 5.95, p < .05).

Figure 2. Relationship between having trouble sleeping at ages 12–14 and self-harm/suicidal behavior at ages 15–17.

Note. The association between “having trouble sleeping” and self-harm/suicidal attempts was statistically significant (χ2 (1) = 11.12, p = .001).

3.2 The relationships among parental alcoholism, sleep problems, and suicidality

Having an alcoholic parent had no significant association with self-reported sleep problems. COAs did not report more sleep problems than non-COAs (trouble sleeping: χ2 (1) = .07, p = .80; overtiredness: χ2 (1) =.91, p = .34; nightmares: χ2 (1) =.10, p = .75). Having an alcoholic parent was also not associated with suicidal thoughts (ages 12–14: χ2 (1) =.01, p = .93; ages 15–17: χ2 (1) =.10, p = .76) or self-harm/suicidal behaviors in adolescence (ages 12–14: χ2 (1) =.05, p = .83; ages 15–17: χ2 (1) = .36, p = .55).

3.3 The relationship between sleep problems and suicidal thoughts

We used parental alcoholism and history of suicidal thoughts or attempts, gender and age of the adolescent participants, and the following variables at ages 12–14 (suicidal thoughts, depressive symptoms, aggressive behaviors, substance-related problems, overtiredness, nightmares, and having trouble sleeping) to predict suicidal thoughts at ages 15–17 in a direct logistic regression model (Table 2). The analysis showed that controlling for all variables into the model, having trouble sleeping at ages 12–14 significantly predicted suicidal thoughts at ages 15–17. Those who had trouble sleeping in early adolescence were more than two times as likely than those without trouble sleeping to think about killing oneself in late adolescence (Odds ratio: 2.41, p <.05). None of the other variables significantly predicted adolescent suicidal thoughts. Results of the sequential regression model were essentially the same (Table 2). Entering sleep variables in the last block did not change the results.

Table 2.

Odds ratio for suicidal thoughts at ages 15–17

| Direct logistic regression | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| thoughts about killing oneself (ages 12–14) | 1.90 | 0.46 -7.79 | 0.37 |

| gender | 0.88 | 0.37 - 2.08 | 0.77 |

| age | 0.99 | 0.65 - 1.51 | 0.95 |

| paternal alcoholism | 1.07 | 0.41 - 2.76 | 0.89 |

| maternal alcoholism | 1.17 | 0.50 - 2.77 | 0.72 |

| paternal suicidal ideation or attempts | 2.11 | 0.94 - 4.72 | 0.07 |

| maternal suicidal ideation or attempts | 1.36 | 0.60 - 3.10 | 0.46 |

| depressive symptoms (ages 12–14) | 0.91 | 0.12 - 6.67 | 0.88 |

| aggressive behavior (ages 12–14) | 0.98 | 0.91 - 1.09 | 0.10 |

| alcohol or drug use related problems (ages 12–14) | 1.19 | 0.33 - 4.30 | 0.79 |

| trouble sleeping (ages 12–14) | 2.44 | 1.03 - 5.75 | 0.04* |

| overtired (ages 12–14) | 1.09 | 0.43 - 2.74 | 0.86 |

| nightmares (ages 12–14) | 0.48 | 0.20 - 1.17 | 0.11 |

| Sequential logistic regression | |||

| Block 1 | |||

| thoughts about killing oneself (ages 12–14) | 2.17 | 0.69 - 6.81 | 0.18 |

| gender | 0.98 | 0.43 - 2.24 | 0.98 |

| age | 1.07 | 0.71 - 1.59 | 0.76 |

| Block 2 | |||

| paternal alcoholism | 1.08 | 0.46 - 2.86 | 0.87 |

| maternal alcoholism | 1.14 | 0.48 - 2.55 | 0.78 |

| paternal suicidal ideation or attempts | 2.14 | 0.99 - 4.62 | 0.05* |

| maternal suicidal ideation or attempts | 1.42 | 0.63 - 3.16 | 0.40 |

| Block 3 | |||

| depressive symptoms (ages 12–14) | 0.91 | 0.12 - 6.67 | 0.88 |

| aggressive behavior (ages 12–14) | 0.98 | 0.91 - 1.09 | 0.10 |

| alcohol or drug use related problems (ages 12–14) | 1.19 | 0.33 - 4.30 | 0.79 |

| trouble sleeping (ages 12–14) | 2.44 | 1.03 - 5.75 | 0.04* |

| overtired (ages 12–14) | 1.09 | 0.43 - 2.74 | 0.86 |

| nightmares (ages 12–14) | 0.48 | 0.20 - 1.17 | 0.11 |

Note.

All variables were entered simultaneously in the analyses.

p <.05.

3.4 The relationship between sleep problems and self-harm/suicidal behaviors

Results from the direct logistic regression model self-harm/suicidal behaviors at ages 15-17 were not significantly related to demographic variables, parental alcoholism, parental history of suicidal ideation or attempts, adolescents’ own previous self-harm/suicidal behaviors, overtiredness, or having nightmares (Table 3). Controlling for these other variables in the model, the only significant predictor was trouble sleeping at ages 12–14. Participants who had trouble sleeping in early adolescence were four times more likely to deliberately harm themselves or attempt suicide in late adolescence (Odds ratio: 4.1, p <.01). Results of the sequential regression model were consistent with that of the direct logistic regression model (Table 3).

Table 3.

Odds ratio for self-harm/suicidal behavior at ages 15–17

| Direct logistic regressiona | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| deliberately try to hurt or kill oneself (ages 12–14) | 3.79 | .53 - 26.88 | 0.18 |

| gender | 0.81 | 0.28 - 2.36 | 0.71 |

| age | 1.23 | 0.73 - 2.08 | 0.43 |

| paternal alcoholism | 1.10 | 0.35 - 3.47 | 0.87 |

| maternal alcoholism | 1.02 | 0.36 - 2.90 | 0.98 |

| paternal suicidal ideation or attempts | 1.35 | 0.48 - 3.82 | 0.57 |

| maternal suicidal ideation or attempts | 2.65 | 1.01 - 6.95 | 0.05* |

| depressive symptoms (ages 12–14) | 1.64 | 0.18 - 15.06 | 0.66 |

| aggressive behavior (ages 12–14) | 0.94 | 0.84 - 1.06 | 0.31 |

| alcohol or drug use related problems (ages 12–14) | 1.97 | 0.48 - 7.89 | 0.34 |

| trouble sleeping (ages 12–14) | 4.06 | 1.42 - 11.62 | 0.01** |

| overtired (ages 12–14) | 1.19 | 0.38 - 3.66 | 0.77 |

| nightmares (ages 12–14) | 0.78 | 0.27 - 2.24 | 0.64 |

| Sequential logistic regression | |||

| Block 1 | |||

| deliberately try to hurt or kill oneself (ages 12–14) | 3.51 | 0.71 - 17.28 | 0.12 |

| gender | 0.87 | 0.32 - 2.35 | 0.78 |

| age | 1.36 | 0.84 - 2.21 | 0.21 |

| Block 2 | |||

| paternal alcoholism | 1.05 | 0.35 - 3.17 | 0.93 |

| maternal alcoholism | 1.05 | 0.38 - 2.90 | 0.93 |

| paternal suicidal ideation or attempts | 1.44 | 0.55 - 3.80 | 0.46 |

| maternal suicidal ideation or attempts | 2.64 | 1.05 - 6.68 | 0.04* |

| Block 3 | |||

| depressive symptoms (ages 12–14) | 1.64 | 0.18 - 15.06 | 0.66 |

| aggressive behavior (ages 12–14) | 0.94 | 0.84 - 1.06 | 0.31 |

| alcohol or drug use related problems (ages 12–14) | 1.97 | 0.48 - 7.89 | 0.34 |

| trouble sleeping (ages 12–14) | 4.06 | 1.42 - 11.62 | 0.01** |

| overtired (ages 12–14) | 1.19 | 0.38 - 3.66 | 0.77 |

| nightmares (ages 12–14) | 0.78 | 0.27 - 2.24 | 0.64 |

Note.

All variables were entered simultaneously in the analyses.

p<.05.

p <.01.

4. Discussion

The main finding of this study is that self-reported trouble sleeping between the ages of 12 and 14 was significantly associated with suicidal thoughts and self-harm/suicidal behaviors at ages 15–17, while adjusting for age, gender, prior suicidality, depressive symptoms, aggressive behavior, substance-related problems, COA status, and parental suicidal thoughts. This is to our knowledge the first prospective study of this relationship performed in the U.S. with a high-risk sample of adolescents.

Past research has found a strong association between depressive symptoms and suicidal behavior (Bettes and Walker, 1986; Ivarsson et al., 1998; Kovacs et al., 1993; Nrugham et al., 2008). However, a previous longitudinal study conducted in Norway failed to find a relationship between insomnia at age 15 and suicide attempts by age 20 after controlling for depressive symptoms (Nrugham et al., 2008). As insomnia and other sleep disturbances are often associated with depression, it is important to examine whether sleep problems predict suicidal behavior after controlling for depressive symptoms. This study found that having trouble sleeping prospectively predicted suicidal ideation and self-harm/suicidal behavior, even after controlling for depressive symptoms. Our study and the Nrugham et al. (2008) study differ in terms of sample characteristics (general students followed from ages 15 to 20 vs. high-risk community adolescents followed from ages 12 to 17; more girls vs. more boys); duration of follow-up (5 years vs. 3 years); instruments used to measure sleep, suicidality, and depression; and possibly culture. These differences might have explained the discrepancies in the results of the two studies. In any event, the present study draws attention to the potential importance of sleep problems as a marker for suicidal behavior in adolescence. Existing research also showed that sleep problems also prospectively predict depression (Gregory et al., 2005; Gregory and O'Connor, 2002), anxiety disorders (Gregory et al., 2005; Gregory and O'Connor, 2002), onset of substance use (Wong et al., 2004; Wong et al., 2009), and number of alcohol and drug related problems (Wong et al., 2010). Thus sleep problems may be markers of a spectrum of risky behaviors, including suicidality.

Two other studies reported that nightmares (Choquet and Menke, 1990) and tiredness (Choquet et al., 1993) predicted suicidality in adolescents. Our study differs, however, by including all three sleep variables (insomnia, nightmares, and overtiredness) simultaneously in the multivariate analyses, which allows the variables to statistically control for one another. This is important as the three variables are correlated with one another in this study. Our results show that controlling for nightmares, overtiredness, depressive symptoms, and other variables in the study, having trouble sleeping at ages 12–14 significantly predicted suicidal behavior at ages 15–17. Future studies need to simultaneously assess the role of multiple sleep variables on suicidal behavior.

Contrary to our first two hypotheses, COAs were no more likely than non-COAs to report either sleep problems or suicidality as measured in this study. Adolescence is a time of both frequent sleep problems (Hagenauer et al., 2009; Johnson et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2008) and increased suicidality (Cash and Bridge, 2009). We can speculate, therefore, that a ceiling effect during this age period may exist for these problems that is unaffected by COA status.

This study has several limitations. First, all measures were based on self-report which are subject to response and recall bias. No objective measures of sleep such as polysomnography or actigraphy were included. Second, self-harm/suicidal behaviors were assessed by the single item, “deliberately try to harm or kill yourself.” Unfortunately, this compound item included both attempts to harm oneself and attempts to kill oneself, making it impossible to measure them separately. While trying to kill oneself is the definition of a suicide attempt, deliberate attempts to harm oneself may lack the intent to commit suicide. Therefore, this item more correctly refers to deliberate self-harm behavior that includes, but is not limited to, suicide attempts. Third, suicidal behavior and sleep variables were measured by single items. Although these items have face validity and have been used by other studies (Herba et al., 2008; Johnson and Breslau, 2001; Resch et al., 2008), the reliability of these measures is unknown. The lack of an association between overtiredness, or having nightmares and subsequent suicidal ideation and self-harm behaviors could be in part, due to unknown measurement error. Future studies should use multiple items to measure these variables and estimate measurement error by doing latent variable analyses. Fourth, girls were underrepresented in this study, whereas Caucasians and COAs were overrepresented. Although gender and COA status were controlled for statistically, other ethnic/racial groups were not included; thus, results may not generalize to all adolescents.

Finally, a number of other predictors of adolescent suicidality were not included such as impulsivity and physical and/or sexual abuse (Cash and Bridge, 2009). For instance, sexual abuse (Noll et al., 2006) is associated with insomnia, and could potentially preclude the latter’s significance as a predictor of suicidality. Further studies employing larger sample sizes will need to control for these and other known risk factors. Nevertheless, from a clinical point of view, patients often feel more comfortable discussing sleep problems than either physical or sexual abuse. Therefore, sleep problems can be a useful marker for other risk factors during the interview process.

In summary, trouble sleeping was a predictor of both suicidal thoughts and self-harm/suicidal behavior in this longitudinal study of adolescents while controlling for baseline depressive symptoms and suicidality. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of such a relationship in a prospective study of adolescents. Of particular clinical interest, children were between the ages of 12 and 14 at the baseline interview, which preceded the well-established high-risk period for suicide in the general population of 15–24 year-olds. Moreover, trouble sleeping is relatively easy to assess in the clinical interview, and can begin a process of gentle questioning for other potential risk factors that may be less comfortable for adolescents to discuss. Accordingly, clinicians should inquire about sleep disturbances when assessing for suicidality in adolescents. Finally, future research should determine if early intervention with sleep disturbances reduces the risk for suicidality in adolescents.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Maria M. Wong, Department of Psychology, Idaho State University

Kirk J. Brower, Department of Psychiatry, University of Michigan

Robert A. Zucker, Departments of Psychiatry & Psychology, University of Michigan

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Agargun MY, Besiroglu L, Cilli AS, et al. Nightmares, suicide attempts, and melancholic features in patients with unipolar major depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;98:267–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailly D, Bailly-Lambin I, Querleu D, Beuscart R, Collinet C. Sleep in adolescents and its disorders: a survey in schools. L'Encéphale. 2004;30:352–359. doi: 10.1016/s0013-7006(04)95447-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbe RP, Williamson DE, Bridge JA, et al. Clinical differences between suicidal and nonsuicidal depressed children and adolescents. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66:492–498. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin M. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory. Clinical Psychology Review. 1988;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettes BA, Walker E. Symptoms associated with suicidal behaviour in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1986;14:591–604. doi: 10.1007/BF01260526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll BJ, Fielding JM, Blashki TG. Depression rating scales: a critical review. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1973;28:361–366. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1973.01750330049009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash SJ, Bridge JA. Epidemiology of youth suicide and suicidal behavior. Current Opinions in Pediatrics. 2009;21:613–619. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32833063e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chellappa SL, Araujo JF. Sleep disorders and suicidal ideation in patients with depressive disorder. Psychiatry Research. 2007;153:131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choquet M, Kovess V, Poutignat N. Suicidal thoughts among adolescents: an intercultural approach. Adolescence. 1993;28:649–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choquet M, Menke H. Suicidal thoughts during early adolescence: prevalence, associated troubles and help-seeking behavior. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1990;81:170–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1990.tb06474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke GN, Lewinsohn PM, Hops H, Seeley JR. A self- and parent-report measure of adolescent depression: The Child Behavior Checklist Depression scale (CBCL-D) Behavioral Assessment. 1992;14:443–463. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl RE, Williamson DE, Bertocci MA, Stolz MV, Ryan ND, Ehlers CL. Spectral analyses of sleep EEG in depressed offspring of fathers with or without a positive history of alcohol abuse or dependence: a pilot study. Alcohol. 2003;30:193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith SK, Pellmar TC, Kleineman AM, Bunney WE. Reducing suicide: a national imperative. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein TR, Bridge JA, Brent DA. Sleep disturbance preceding completed suicide in adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:84–91. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory AM, Caspi A, Eley TC, Moffitt TE, O'Connor TG, Poulton R. Prospective longitudinal associations between persistent sleep problems in childhood and anxiety and depression disorders in adulthood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;(33):157–163. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-1824-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory AM, O'Connor TG. Sleep problems in childhood: A longitudinal study of developmental change and association with behavioral problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41(8):964–971. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200208000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagenauer MH, Perryman JI, Lee TM, Carskadon MA. Adolescent changes in the homeostatic and circadian regulation of sleep. Developmental Neuroscience. 2009;31:276–284. doi: 10.1159/000216538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–61. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. Standardised assessment and recording of depressive symptoms. Psychiatria, Neurologia, Neurochirurgia. 1969;72(2):201–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the united states: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007 July 1;64:830–842. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herba CM, Ferdinand RF, Stijnen T, et al. Victimization and suicide ideation in the trails study: specific vulnerabilities of victims. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:867–876. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivarsson T, Larsson B, Gillberg C. A 2-4 year follow-up of depressive symptoms suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among adolescent psychiatric inpatients. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;7:96–104. doi: 10.1007/s007870050053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EO, Breslau N. Sleep problems and substance use in adolescence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2001;64:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00222-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EO, Roth T, Schultz L, Breslau N. Epidemiology of DSM-IV insomnia in adolescence: lifetime prevalence, chronicity, and an emergent gender difference. Pediatrics. 2006;117:247–256. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M, Goldston D, Gatsonis C. Suicidal behaviours and childhood-onset depressive disorders: a longitudinal investigation. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32:8–20. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199301000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Psychosocial risk factors for future adolescent suicide attempts. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:297–305. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman DZ. Children of alcoholics: an update. Current Opinions in Pediatrics. 2000;12:336–340. doi: 10.1097/00008480-200008000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. Sleep and adolescent suicidal behavior. Sleep. 2004;27:1351–1358. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.7.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Buysse DJ. Sleep and youth suicidal behaviour: a neglected field. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2006;19:288–293. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000218600.40593.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Zhao Z, Jia C, Buysse DJ. Sleep patterns and problems among Chinese adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008;121:1165–1173. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGirr A, Renaud J, Seguin M, et al. An examination of DSM-IV depressive symptoms and risk for suicide completion in major depressive disorder: a psychological autopsy study. Journal of Affective Discord. 2007;97:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll JG, Trickett PK, Susman EJ, Putnam FW. Sleep disturbances and childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2006;31:469–480. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nrugham L, Larsson B, Sund AM. Specific depressive symptoms and disorders as associates and predictors of suicidal acts across adolescence. Journal of Affective Discord. 2008;111:83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resch F, Parzer P, Brunner R. Self-mutilation and suicidal behaviour in children and adolescents: prevalence and psychosocial correlates: Results of the BELLA study. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;17:92–98. doi: 10.1007/s00787-008-1010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan JL, Ratcliff KS. The NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule: its history, characteristics and validity. St. Louis, MO: Washington University School of Medicine; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Selzer ML, Vinokur A, van Rooijen L. A self-administered short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (SMAST) Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1975;36:117–126. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1975.36.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjostrom N, Waern M, Hetta J. Nightmares and sleep disturbances in relation to suicidality in suicide attempters. Sleep. 2007;30:91–95. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarokh L, Carskadon MA. Sleep electroencephalogram in children with a parental history of alcohol abuse/dependence. Journal of Sleep Research. 2009;19:165–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2009.00763.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turvey CL, Conwell Y, Jones MP, et al. Risk factors for late-life suicide: a prospective, community-based study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2002;10:398–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallander MA, Johansson S, Ruigomez A, Garcia Rodriguez LA, Jones R. Morbidity associated with sleep disorders in primary care: a longitudinal cohort study. Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2007;9:338–345. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v09n0502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojnar M, Ilgen MA, Wojnar J, McCammon RJ, Valenstein M, Brower KJ. Sleep problems and suicidality in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2009;43:526–531. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MM, Brower KJ, Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA. Sleep problems in early childhood and early onset of alcohol and other drug use in adolescence. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 2004;28:578–587. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000121651.75952.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MM, Brower KJ, Nigg JT, Zucker RA. Childhood sleep problems, response inhibition and alcohol and drug outcomes in adolescence and young adulthood. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 2010;34:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MM, Brower KJ, Zucker RA. Childhood sleep problems, early onset of substance use and behavioral problems in adolescence. Sleep Medicine. 2009;10:787–796. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Donovan JE, Masten AS, Mattson ME, Moss HB. Early developmental processes and the continuity of risk for underage drinking and problem drinking. Pediatrics. 2008;121:252–272. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2243B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Fitzgerald HE. Early developmental factors and risk for alcohol problems. Alcohol Health and Research World. 1991;15:18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Fitzgerald HE. Family study of risk for alcoholism over the life course. Appendix 9.3 Assesment protocol: Description of instruments and copies of contact schedules. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Fitzgerald HE, Noll RB. Drinking and drug history. Unpublished instrument. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Fitzgerald HE, Refior SK, Puttler LI, Pallas DM, Ellis DA. The clinical and social ecology of childhood for children of alcoholics: Description of a study and implications for a differentiated social policy. In: Fitzgerald HE, Lester BM, Zuckerman BS, editors. Children of addiction: Research, health, and policy issues. New York: Routledge Falmer; 2000. pp. 109–141. [Google Scholar]