Abstract

Nucleolar dominance is a widespread epigenetic phenomenon, describing the preferential silencing of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes inherited from one progenitor of an interspecific hybrid, independent of maternal or paternal effects. In the allotetraploid hybrid plant species Arabidopsis suecica, A. thaliana-derived rRNA genes are silenced whereas the A. arenosa-derived rRNA genes are transcribed. We reported previously on an RNAi-based screen of DNA methyltransferases, methylcytosine binding proteins and RNA-dependent DNA methylation pathway proteins that identified specific activities required for the establishment or enforcement of nucleolar dominance. Here we present additional molecular and cell biological evidence that siRNA-directed cytosine methylation and the methylcytosine binding protein MBD6 bring about large-scale chromosomal effects on rRNA gene loci subjected to nucleolar dominance in A. suecica.

Key words: ribosomal RNA, rRNA, Arabidopsis suecica, nucleolar dominance, siRNAs, methylcytosine-binding proteins, DNA methylation, heterochromatin

DRM2 Methyltransferase Activity and MBD6 Recruitment are Required for Nucleolar Dominance

Previous work by our group identified a self-reinforcing mechanism for the establishment or maintenance of nucleolar dominance involving concerted changes in histone deacetylation and DNA methylation. Initially, chemical inhibition of histone deacetylation, using trichostatin A (TSA) or sodium butyrate, or inhibition of DNA methylation using 5-aza-2′ deoxycytosine (5aza-dC) were found to derepress silenced rRNA genes subjected to nucleolar dominance in Brassica or Arabidopsis allotetraploid hybrids.1,2 We subsequently undertook RNAi knockdown screens to identify specific chromatin modifying activities required for nucleolar dominance. A critical activity identified in a screen of predicted histone deacetylases is HDA6. HDA6 has in vitro histone deacetylase activity that is inhibited by TSA, thus linking the TSA-mediated disruption of nucleolar dominance with impaired HDA6 function.3 A separate screen explored the basis for 5aza-dC-mediated disruption of nucleolar dominance by targeting the DNA methyltransferase family.4 The Arabidopsis thaliana genome encodes eleven predicted DNA methyltransferases, seven of which are expressed, but only three of which have known functions. MET1 (METHYLTRANSFERASE 1)5 methylates primarily at CG dinucleotides, but also methylates at CHG motifs. CMT3 (CHROMOMETHYLASE 3)6 methylates CHG motifs. DRM2 (DOMAINS REARRANGED METHYLTRANSFERASE 2)7 methylates cytosines in all sequence contexts, including asymmetric CHH motifs. We used RNAi to target all of the expressed DNA methyltransferases in A. suecica and showed that MET1 and CMT3 were efficiently knocked down without affecting nucleolar dominance. In contrast, A. suecica DRM2-RNAi lines were found to release silencing of A. thaliana rRNA genes.

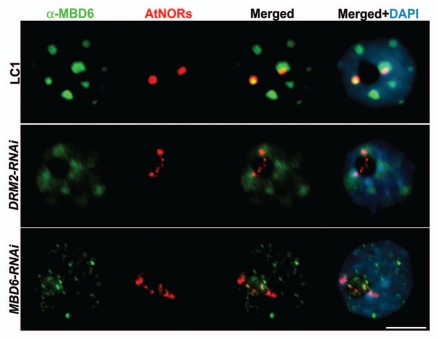

In mammals, the methylcytosine-binding domain protein (MBD) MeCP2 interacts with the histone deacetylase HDAC1,8,9 and the DNA methyltransferase DNMT1,10 to mediate transcriptional repression. We generated A. suecica RNAi knockdown lines targeting the 13 predicted MBD proteins to test their involvement in nucleolar dominance, possibly as partners with DRM2 and HDA6. We found that A. thaliana rRNA genes are derepressed in A. suecica MBD6-RNAi and MBD10-RNAi lines.4 MBD10 was found to localize throughout the nucleoplasm, without any preferential association with rRNA loci, suggesting that it plays a general role in the nucleus. In contrast, MBD6 preferentially localizes at chromocenters,11 the highly condensed regions of the genome that stain intensively with DNA-binding dyes, such as DAPI. Chromocenters are sites where heterochromatin coalesces, including centromeric repeats, silent rRNA genes and other heterochromatic repeats.12 Using an antibody raised against MBD6, we observed that in A. thaliana drm2 mutants, localization of MBD6 is lost specifically at the chromocenters that include the rRNA gene repeats, or NORs (nucleolus organizer regions). Consistent with this previous result, MBD6 is mis-localized in A. suecica DRM2-RNAi nuclei (Fig. 1). In A. suecica MBD6-RNAi nuclei, MBD6 signals are strongly reduced relative to wild-type, indicating that the RNAi-inducing transgene is functional. In both A. suecica DRM2- and MBD6-RNAi lines, A. thaliana-derived NORs are substantially decondensed, a cytological manifestation of the derepression of A. thaliana rRNA genes in these lines.2,3,13 Taken together with chromatin immunoprecipitation evidence that the association of MBD6 with rRNA gene promoters is lost in A. suecica DRM2-RNAi4 plants, our observations indicate that MBD6 recognizes DRM2-mediated cytosine methylation patterns or chromatin modifications in the formation of repressive chromatin complexes.

Figure 1.

Combined DNA-FISH/immunolocalization in A. suecica interphase nuclei, comparing wild-type (LC1), DRM2-RNAi and MBD6-RNAi lines. DNA-FISH with an A. thaliana rRNA gene probe (red) shows decondensation of rRNA gene arrays (Nucleolus Organizer Regions, or NORs) in RNAi lines relative to wild-type and the loss of NOR association with MBD6, immunolocalized using anti-MBD6 antibody (green). Colocalization of rRNA and MBD6 signals produces a yellow signal in merged images. DNA was counterstained with DAPI (blue). Representative nuclei are shown (size bar = 10 µm).

24 nt siRNAs and Nucleolar Dominance

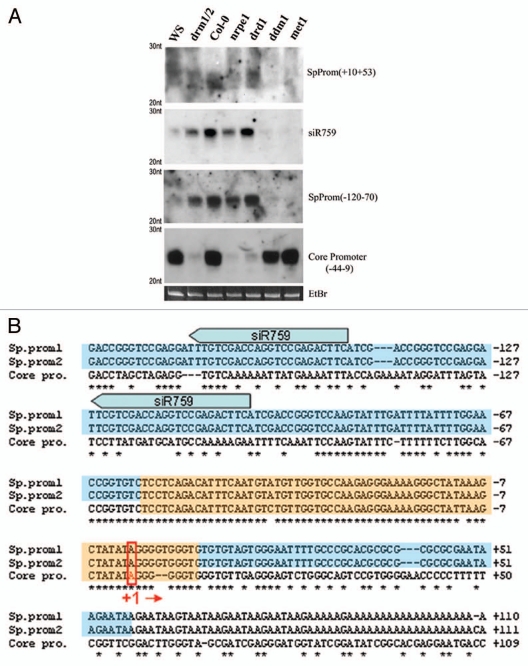

We showed previously that biogenesis of 24 nt siRNAs homologous to the core promoter region of 45S rRNA genes is dependent on RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) pathway proteins.14 Because DRM2 and HDA6 are strongly implicated in RdDM in Arabidopsis,15–18 as well as nucleolar dominance, we investigated the role of the RdDM pathway members, RDR2 and DCL3, in 45S rRNA siRNA production and nucleolar dominance. We analyzed deep sequencing data from two small RNA libraries19,20 and confirmed that the rRNA gene promoter region is a hotspot for 24 nt siRNA accumulation. Moreover, siRNAs corresponding to repetitive regions throughout the rRNA intergenic spacer (IGS) are predominantly 23–24 nt in size and dependent on RNA polymerase IV (Pol IV), RDR2 and DCL3 (data not shown). Interestingly, DNA methylation feeds back on the biogenesis of siRNAs and we find that different components of the DNA methylation machinery affect the abundance of siRNAs homologous to different regions of the IGS (Fig. 2). For instance, accumulation of siRNAs corresponding to the gene promoter and spacer promoters, which share almost perfect sequence similarity from nucleotide positions −50 to +15 (+1 is defined as the Pol I transcription start site), is dependent on DRM2 and the putative chromatin remodeler DRD1,21 but independent of MET1 or DDM1. In contrast, siRNAs matching other regions of the IGS require MET1 and DDM1, but not DRM2 or DRD1 (Fig. 2). Centromeric siRNAs also require MET1 and DDM1 for their biogenesis or accumulation.22,23 Collectively, our data indicates that cytosine methylation feeds back on the production of siRNAs, but methylation in different cytosine contexts is important in different genomic regions, even in different regions of the same gene.

Figure 2.

(A) RNA blot analysis of small RNAs homologous to 45S rRNA gene intergenic spacer (IGS) sequences in A. thaliana DNA methyltransferase and chromatin remodeling mutants. All mutant lines tested are in the Col-0 ecotype except drm1/drm2 which is in the WS genetic background. Probe coordinates are relative to the transcription start site, defined as +1. (B) Sequence alignment of rRNA core and spacer promoter regions. Orange boxes represent regions for which siRNA biogenesis requires DRM2 and DRD1. Blue boxes represent MET1 and DDM1-dependent siRNA species. Block arrows show two of the multiple sites homologous to siR759 present in the 45S rRNA IGS repeats. Pol I transcription start site (+1) is highlighted.

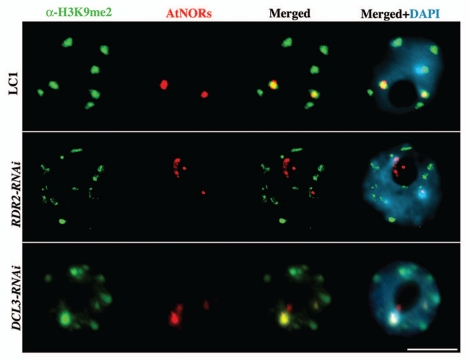

De novo cytosine methylation by DRM2 is thought to be entirely RNA-directed.24 Therefore, our finding that DRM2 is required for nucleolar dominance in A. suecica, combined with the occurrence of abundant 24 nt siRNAs that match rRNA gene promoter and IGS sequences, suggested a functional role for siRNA-directed rRNA gene silencing. To test this hypothesis, we targeted DCL3 and RDR2 for RNAi-mediated knockdown in A. suecica. In the resulting transgenic lines, DCL3 and RDR2 mRNA levels were reduced, as were siRNAs corresponding to both A. arenosa and A. thaliana 45S rRNA genes.4 Importantly, nucleolar dominance was disrupted, such that A. thaliana 45S rRNA genes are derepressed in the RNAi lines. Cytologically, A. thaliana rRNA genes in wild-type A. suecica are organized in one or two highly compact foci associated with histone H3 that is dimethylated on lysine 9 (H3K9me2), a mark of silent heterochromatin enriched at chromocenters.13 By combining in situ-immunolocalization with DNA-FISH in DCL3- and RDR2-RNAi lines, we observe the decondensation of A.thaliana 45S rRNA gene chromatin and the loss of their association with H3K9me2 (Fig. 3; Table 1) as previously described in other mutants that disrupt nucleolar dominance.2,3,13

Figure 3.

Derepression of A. thaliana 45S rRNA genes in A. suecica DCL3- and RDR2-RNAi lines results in chromatin decondensation (red) and partial loss of its association to H3dimethylK9 (green). DNA was counterstained with DAPI (blue). Representative interphase nuclei are shown (size bar = 10 µm).

Table 1.

Decondensation of A. thaliana rDNA foci is accompanied by loss of association to H3K9me2

| A. thaliana 45S rDNA foci number (%) | ||||

| ≤2 | >2 | Fisher | n | |

| LC1 (wt) | 85.4 | 14.6 | 82 | |

| LC1 RDR2-RNAi | 41.4 | 58.6 | p < 0.0001 | 128 |

| LC1 DCL3-RNAi | 46.9 | 53.1 | p < 0.0001 | 113 |

| Total | Partial | |||

| H3K9me2 vs. rDNA colocalization | ||||

Frequency (%) of nuclei observed with distinct numbers of A. thaliana rRNA FISH signals in A. suecica LC1 and progeny of T1 transformants of A. suecica RDR2-RNAi and A. suecica DCL3-RNAi lines. A. thaliana NORs are considered partially localized with H3K9me2 when decondensed (>2 foci) and colocalized when condensed (≤2 foci). Fisher's exact test was used to compare distributions between LC1 and transgenic lines.

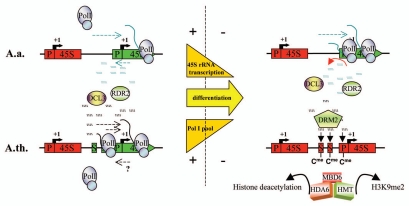

A Model for siRNA-Dependent Establishment of Nucleolar Dominance in A. suecica

Our studies show that nucleolar dominance in A. suecica requires RdDM pathway proteins RDR2 and DCL3, the de novo DNA methyltransferase DRM2, the methylcytosine binding protein MBD6 and the histone deacetylase HDA6. We propose that siRNAs direct DRM2 methylation activity to promoter and or other regulatory regions of the IGS and that these de novo methylation patterns are in turn recognized by MBD6. We hypothesize that MBD6 interacts with other corepressors to bring about gene silencing, rendering rRNA gene promoters inaccessible to the Pol I transcription machinery (Fig. 4). Because we observe higher siRNA accumulation levels in MBD6-RNAi lines compared to wild-type,4 we also think that MBD6-mediated repression limits further production of siRNA precursor transcripts. The identities of co-repressor activities that might interact with MBD6 to bring about nucleolar dominance are unknown, but our data suggest that HDA6 is likely responsible for the majority of the histone deacetylation activity involved in rRNA gene silencing3 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

A model for A. thaliana derived rRNA gene silencing in A. suecica. In early development, both parental sets of rRNA gene are active in A. suecica.37 As protein synthesis requirements decrease in differentiated mature leaf tissues, rRNA gene transcription is epigenetically downregulated in a process involving RNA-dependent DNA methylation. Non-coding RNAs originating in the intergenic spacer serve as substrates for RDR2 and DCL3 dependent 24 nt siRNA biogenesis which target promoter and or other regulatory elements for DRM2-mediated de novo cytosine methylation. A. thaliana genes are preferentially silenced via an unknown mechanism that involves siRNAs capable of discriminating between the parental sets of rRNA genes. MBD6 recognizes DRM2 dependent cytosine methylation patterns and likely recruits HDA6 and histone methyltransferase activities to reinforce the heterochromatic state and lock in the silencing of IGS and 45S rRNA transcription. (S) spacer promoter; (P) core promoter

Future Directions

Our finding that siRNAs are involved in chromosomal silencing on a multi-megabase scale in nucleolar dominance is not known to be the case in all large-scale gene silencing phenomena, but non-coding RNA molecules are clearly involved in X-chromosome inactivation and gametic imprinting in mammals.25–27 Moreover, rRNA gene silencing in mouse28,29 has been found to involve highly structured RNAs of 200–300 nt that are processed from longer transcripts originating within the IGS, presumably from spacer promoters. These RNAs are required for the NoRC (nucleolar remodeling complex) repressor complex to localize to the core promoter region and ultimately bring about rRNA gene silencing.28,30 Although the size of the RNA molecules involved in rRNA gene silencing appear to differ between plants and mice (i.e., siRNAs versus long RNAs), the involvement of IGS transcripts is a common link. The origins of IGS transcripts giving rise to siRNAs in Arabidopsis requires further investigation in order to determine if they are derived from spacer promoters transcribed by Pol I31,32 or from cryptic promoters recognized by other polymerases, such as Polymerases II, IV or V.

An apparent paradox that requires further study stems from our analyses of siRNAs derived from the 45S rRNA genes inherited from the two progenitors of A. suecica. We have observed that siRNAs derived from A. arenosa rRNA genes are more abundant than siRNAs derived from A. thaliana rRNA genes in mature leaf tissues displaying nucleolar dominance. This is unexpected given that the A. arenosa-derived genes are active and the A. thaliana-derived rRNA genes are silenced in a siRNA-dependent manner. One possibility may be that siRNAs act at a very specific time in early development when nucleolar dominance is first established. Later, in tissues of mature plants, we may only be seeing siRNAs involved in regulating the number of active genes among the dominant class, as part of the dosage control system that regulates rRNA genes in all eukaryotes.2,32–34

Our understanding of the epigenetic mechanisms regulating nucleolar dominance in A. suecica has advanced greatly in the last decade. Still, a number of questions remain unanswered, including the origins of regulatory IGS transcripts and the timing of their expression, the mechanisms by which chromatin remodeling activities regulate promoter accessibility to the transcription machinery, and the full set of chromatin modifying activities involved in uniparental rRNA gene silencing. By pursuing these questions we hope to ultimately comprehend the enduring biological mystery that is nucleolar dominance, an enigma that has puzzled the scientific community since the pioneering work of Navashin and McClintock35,36 nearly 80 years ago.

Acknowledgements

We thank Thomas Ream, Alexa Vitins and Sarah Tucker for helpful insights on the manuscript. P.C.N. performed the siRNA blots and DCL3 and RDR2 knockdowns. O.P. performed all microscopy. S.P. conducted DNA methyltransferase and MBD knockdown screens. P.C.N. and C.S.P. wrote the manuscript. This work was supported by United States NIH grant GM60380 to C.S.P. RNAi vector development was supported by United States National Science Foundation grant no. 9975930. P.C.N. was supported by grant SFRH/BPD/30386/2006 from F.C.T., Portugal. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of our sponsors.

Extra View to: Preuss SB, Costa-Nunes P, Tucker S, Pontes O, Lawrence RJ, Mosher R, et al. Multimegabase silencing in nucleolar dominance involves siRNA-directed DNA methylation and specific methylcytosine-binding proteins. Mol Cell. 2008;32:673–684. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.11.009.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/nucleus/article/11741

References

- 1.Chen ZJ, Pikaard CS. Epigenetic silencing of RNA Polymerase I transcription: a role for DNA methylation and histone modification in nucleolar dominance. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2124–2136. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.16.2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrence RJ, Earley K, Pontes O, Silva M, Chen ZJ, Neves N, et al. A concerted DNA methylation/histone methylation switch regulates rRNA gene dosage control and nucleolar dominance. Mol Cell. 2004;13:599–609. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Earley K, Lawrence RJ, Pontes O, Reuther R, Enciso AJ, Silva M, et al. Erasure of histone acetylation by Arabidopsis HDA6 mediates large-scale gene silencing in nucleolar dominance. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1283–1293. doi: 10.1101/gad.1417706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Preuss SB, Costa-Nunes P, Tucker S, Pontes O, Lawrence RJ, Mosher RA, et al. Multimegabase silencing in nucleolar dominance involves siRNA-directed DNA methylation and specific methylcytosine-binding proteins. Mol Cell. 2008;32:673–684. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kakutani T, Jeddeloh JA, Richards EJ. Characterization of an Arabidopsis thaliana DNA hypomethylation mutant. Nuc Acids Res. 1995;23:130–137. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.1.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao X, Jacobsen SE. Role of the Arabidopsis DRM Methyltransferases in De Novo DNA Methylation and Gene Silencing. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1138–1144. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00925-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao X, Aufsatz W, Zilberman D, Mette MF, Huang MS, Matzke M, et al. Role of the DRM and CMT3 methyltransferases in RNAdirected DNA methylation. Curr Biol. 2003;13:2212–2217. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones PL, Veenstra GJ, Wade PA, Vermaak D, Kass SU, Landsberger N, et al. Methylated DNA and MeCP2 recruit histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Nat Genet. 1998;19:187–191. doi: 10.1038/561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nan X, Ng HH, Johnson CA, Laherty CD, Turner BM, Eisenman RN, et al. Transcriptional repression by the methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 involves a histone deacetylase complex. Nature. 1998;393:386–389. doi: 10.1038/30764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimura H, Shiota K. Methyl-CpG-binding protein, MeCP2, is a target molecule for maintenance DNA methyltransferase, Dnmt1. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4806–4812. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209923200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zemach A, Li Y, Wayburn B, Ben-Meir H, Kiss V, Avivi Y, Kalchenko V, et al. DDM1 binds Arabidopsis methyl-CpG binding domain proteins and affects their subnuclear localization. Plant Cell. 2005;17:1549–1558. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.031567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fransz P, De Jong J, Lysak M, Castiglione MR, Schubert I. Interphase chromosomes in Arabidopsis are organized as well defined chromocenters from which euchromatin loops emanate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14584–14589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212325299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pontes O, Lawrence RJ, Neves N, Silva M, Lee JH, Chen ZJ, et al. Natural variation in nucleolar dominance reveals the relationship between nucleolus organizer chromatin topology and rRNA gene transcription in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11418–11423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1932522100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pontes O, Li CF, Nunes PC, Haag J, Ream T, Vitins A, et al. The Arabidopsis chromatin-modifying nuclear siRNA pathway involves a nucleolar RNA processing center. Cell. 2006;126:79–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aufsatz W, Mette MF, Van Der Winden J, Matzke M, Matzke AJ. HDA6, a putative histone deacetylase needed to enhance DNA methylation induced by double-stranded RNA. EMBO J. 2002;21:6832–6841. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aufsatz W, Stoiber T, Rakic B, Naumann K. Arabidopsis histone deacetylase 6: a green link to RNA silencing. Oncogene. 2007;26:5477–5488. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan SW, Henderson IR, Jacobsen SE. Gardening the genome: DNA methylation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:351–360. doi: 10.1038/nrg1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huettel B, Kanno T, Daxinger L, Bucher E, van der Winden J, Matzke AJ, et al. RNA-directed DNA methylation mediated by DRD1 and Pol IVb: a versatile pathway for transcriptional gene silencing in plants. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1769:358–374. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kasschau KD, Fahlgren N, Chapman EJ, Sullivan CM, Cumbie JS, Givan SA, et al. Genome-wide profiling and analysis of Arabidopsis siRNAs. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:57. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mosher RA, Schwach F, Studholme D, Baulcombe DC. PolIVb influences RNA-directed DNA methylation independently of its role in siRNA biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3145–150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709632105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanno T, Mette MF, Kreil DP, Aufsatz W, Matzke M, Matzke AJ. Involvement of putative SNF2 chromatin remodeling protein DRD1 in RNA-directed DNA methylation. Curr Biol. 2004;14:801–805. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.May BP, Lippman ZB, Fang Y, Spector DL, Martienssen RA. Differential regulation of strand-specific transcripts from Arabidopsis centromeric satellite repeats. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:79. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pontes O, Costa-Nunes P, Vithayathil P, Pikaard CS. RNA polymerase V functions in Arabidopsis interphase heterochromatin organization independent of the siRNA-directed DNA methylation pathway. Molecular Plant. 2009;2:700–710. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssp006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matzke M, Kanno T, Huettel B, Daxinger L, Matzke AJ. RNAdirected DNA methylation and Pol IVb in Arabidopsis. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2006;71:449–459. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2006.71.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Payer B, Lee JT. X-chromosome dosage compensation: How mammals keep the balance. Annu Rev Genet. 2008;47:733–772. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.42.110807.091711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohammad F, Mendal T, Kanduri C. Epigenetics of imprinted long noncoding RNAs. Epigenetics. 2009;4:277–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heard E, Disteche CM. Dosage compensation in mammals: fine-tuning the expression of the X chromosome. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1848–1867. doi: 10.1101/gad.1422906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mayer C, Schmitz KM, Li J, Grummt I, Santoro R. Intergenic transcripts regulate the epigenetic state of rRNA genes. Mol Cell. 2006;22:351–361. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayer C, Neubert M, Grummt I. The structure of NoRC-associated RNA is crucial for targeting the chromatin remodelling complex NoRC to the nucleolus. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:774–780. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strohner R, Nemeth A, Jansa P, Hofmann-Rohrer U, Santoro R, Langst G, et al. NoRC—a novel member of mammalian ISWI containing chromatin remodeling machines. EMBO J. 2001;20:4892–4900. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doelling JH, Gaudino RJ, Pikaard CS. Functional analysis of Arabidopsis thaliana rRNA gene and spacer promoters in vivo and by transient expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7528–7532. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doelling JH, Pikaard CS. The minimal ribosomal RNA gene promoter of Arabidopsis thaliana includes a critical element at the transcription initiation site. Plant J. 1995;8:683–692. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1995.08050683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grummt I, Pikaard CS. Epigenetic mechanisms controlling RNA Polymerase I transcription. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:641–649. doi: 10.1038/nrm1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McStay B. Nucleolar dominance: a model for rRNA gene silencing. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1207–1214. doi: 10.1101/gad.1436906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Navashin M. Chromosome alterations caused by hybridization and their bearing upon certain general genetic problems. Cytologia. 1934;5:169–203. [Google Scholar]

- 36.McClintock B. The relation of a particular chromosomal element to the development of the nucleoli in Zea mays Zeit. Zellforsh mik Anat. 1934;21:294–328. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pontes O, Lawrence RJ, Silva M, Preuss S, Costa-Nunes P, Earley K, et al. Postembryonic establishment of megabase-scale gene silencing in nucleolar dominance. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1157. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]