Abstract

Gastroparesis is a chronic disorder that affects a significant subset of the population. Diabetes mellitus is a risk factor for the development of gastroparesis. Currently, metoclopramide is the only US FDA-approved medication for the treatment of gastroparesis. However, the FDA recently placed a black-box warning on metoclopramide because of the risk of related side effects, including tardive dyskinesia, the incidence of which has been cited to be as high as 15% in the literature. This review will investigate the mechanisms by which metoclopramide improves the symptoms of gastroparesis and will focus on the evidence of clinical efficacy supporting metoclopramide use in gastroparesis. Finally, we seek to document the true complication risk from metoclopramide, especially tardive dyskinesia, by reviewing the available evidence in the literature. Potential strategies to mitigate the risk of complications from metoclopramide will also be discussed.

Keywords: diabetes mellitus, gastroparesis, metoclopramide, tardive dyskinesia

Gastroparesis is a chronic disorder characterized by impaired gastric emptying and altered motility in the upper GI tract in the absence of mechanical obstruction. It is estimated to affect approximately 5 million individuals in the USA and is most often seen in young individuals with a mean age of onset of 34 years. There is a large female-to-male predominance (4:1 ratio), and gastroparesis is frequently seen in diabetics [1]. It generally presents with nonspecific symptoms including early satiation, nausea, emesis, bloating, abdominal pain, heartburn, anorexia and weight loss. Gastroparesis is likely a heterogeneous condition with the most common etiologies having been identified as idiopathic (36%) and diabetes mellitus (30%) [2]. Numerous physiological factors may contribute to symptoms such as abnormalities in liquid and solid meal emptying, emptying of indigestible objects (e.g., fiber), and gastric and proximal small bowel contractility.

The pathophysiology behind gastroparesis is varied and depends upon the etiology of disease. Vagal and/or autonomic neuropathy [3,4] play an important role in the development of diabetic gastroparesis and it is estimated to occur in up to 20–40% of patients with diabetes mellitus [5]. Metabolic abnormalities, especially hyperglycemia, may lead to a delay in gastric emptying, even in healthy individuals [6]. Interruption of hormonal and neural feedback mechanisms is also believed to be significant in the pathogenesis of gastroparesis. The main hormones involved include cholecystokinin from the proximal small bowel as well as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), peptide YY from the distal small bowel and amylin from the pancreas [7]. In addition, there is a loss of expression of neuronal nitric oxide, a loss of enteric neurons, smooth muscle abnormalities and disruption of the network of the interstitial cells of Cajal [8]. This can lead to impaired meal-induced relaxation of the gastric fundus, altered intragastric distribution, fewer antral contractions, tonic motor defects, increased outflow resistance in the pylorus or small intestines and impaired distal regulatory mechanisms [9]. Other etiologies for gastroparesis, including idiopathic causes, are less-well understood and may involve inflammatory mechanisms [10].

However, there is poor correlation between the symptoms of gastroparesis and the severity of delayed gastric emptying. Studies have shown that symptomatic improvement in gastroparesis is only variably correlated with objective improvement in gastric emptying [11–13]. This may be because other pathophysiologic mechanisms (e.g., fundic relaxation, small bowel dysmotility and/or central mechanisms) are improving. However, it is harder to objectively test these factors in clinical practice. It is therfore important to note the distinction between physiologic versus symptomatic improvement of gastroparesis.

Metoclopramide is currently the only medication that is US FDA approved for the treatment of gastroparesis [14]. It was first described by Louis Justin-Besaçon and Charles Laville in 1964 and has been available in the USA since 1979 [15]. However, its use has been increasing over the last decade and is estimated by the FDA to be used by over 2 million Americans currently [16]. Given the recent black-box warning issued by the FDA, this review seeks to highlight the clinical efficacy as well as the adverse risks associated with metoclopramide use and to educate healthcare professionals regarding potential ways to mitigate those risks.

Chemistry

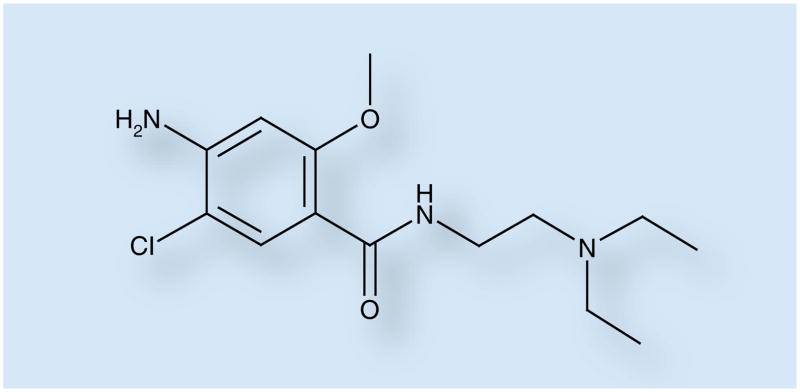

Metoclopramide (4-amino-5-chloro-N-(2-(diethylamino)ethyl)-2-methoxybenzamide) is a substituted benzamide derivative (Figure 1) with a chemical structure similar to procainamide but without anti-arrhythmic effects.

Figure 1. Metoclopramide.

Metoclopramide is a substituted benzamide derivative.

Pharmacokinetics & metabolism

Metoclopramide undergoes first-pass hepatic metabolism and exhibits significant individual variation in metabolism. Metoclopramide is partially metabolized by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) system. It is primarily metabolized via the CYP2D6 iso-form and to a lesser extent by CYP3A and CYP1A2 [17]. Oral bioavailability ranges from 30 to 100%, while approximately 20–30% of the drug is excreted unchanged in the urine [18]. Impaired clearance of the drug is seen in cirrhosis as well as renal insufficiency [19,20]. Interindividual differences in the genotype and phenotype of CYP2D6 may increase the risk for complications from metoclopramide, including tardive dyskinesia (TD) [21]. Moreover, metoclopramide acts not only as a substrate for CYP2D6, but also as a competitive inhibitor of the enzyme. This is similar to other neuroleptic agents, such as haloperidol, thio-ridazine, chlorpromazine, perphenazine and risperidone [22]. As a result, concomitant use of metoclopramide with a neuroleptic agent may increase the bioavailability of each drug and lead to an increased risk of TD.

The vast majority (>90%) of therapeutic drugs are metabolized by CYP1A2, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6 and CYP3A4. Drug–drug interactions occur because of induction and/or inhibition of these isoforms [23]. Patients on metoclopramide are particularly at risk for these interactions because of a likelihood of polypharmacy. Patients with gastroparesis often take medications to relieve pain and nausea, and drugs to treat comorbidities (e.g., diabetes and psychiatric illness). Medications for diabetes, such as amylin analogs (e.g., pram-lintide) and GLP-1 (e.g., exenatide), have been demonstrated to cause or exacerbate delayed gastric emptying [24–26]. Coexisting psychiatric disorders are also common and may contribute to symptoms of gastroparesis. In a cross-sectional study, depression, anxiety and neuroticism were associated with a doubling of the prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in diabetics [27]. In addition, adverse drug reactions involving CYP2D6 are likely to be significant, as 30% of drugs are substrates of this enzyme, including opioids, neuroleptics, antidepressants and cardiac medications [28].

Mechanism of action

Metoclopramide is principally a dopamine D2 antagonist but also acts as an agonist on serotonin 5-HT4 receptors and causes weak inhibition of 5-HT3 receptors.

Actions on gut motility

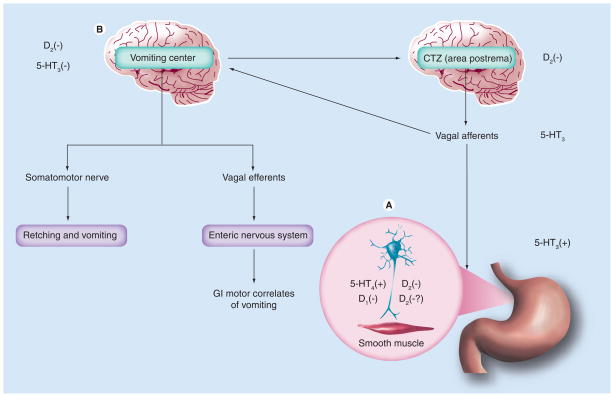

Metoclopramide stimulates gut motility by affecting different receptors in the GI tract (BOX 1). Most importantly, it acts as an antagonist of the dopamine D2 receptor subtype. Dopamine has a direct relaxant effect on the gut by activating muscular D2 receptors in the lower esophageal sphincter and stomach (fundus and antrum). It also inhibits the release of acetylcholine from intrinsic myenteric cholinergic neurons by activating pre-junctional D2 receptors, which leads to an indirect inhibition of the musculature [29]. Metoclopramide promotes gut motility by the following three mechanisms: inhibition of presynaptic and postsynaptic D2 receptors, stimulation of presynaptic excitatory 5-HT4 receptors and antagonism of presynaptic inhibition of muscarinic receptors (Figure 2A). This promotes release of acetylcholine, which in turn leads to increased lower esophageal sphincter (LES) and gastric tone, increased intragastric pressure, improved antroduodenal coordination and accelerated gastric emptying [30–33]. Overall, metoclopramide leads to increased gastric emptying by enhancing antral contractions as well as decreasing postprandial fundus relaxation [34]. However, the prokinetic properties of metoclopramide are limited to the proximal gut [35].

Box 1. Effects of metoclopramide.

Gastric motility

D2 receptor antagonist

Stimulation 5-HT4 receptors

Muscarinic receptor antagonist

Symptoms of gastroparesis

Promotes gastric emptying

Anti-emetic effects via central pathways

Normalization of gastric slow wave dysrhythmias

Modulates visceral hypersensitivity

Figure 2. Mechanism of action of metoclopramide.

(A) Metoclopramide promotes gut motility by inhibiting presynaptic and postsynaptic D2 receptors as well as presynaptic 5-HT4 receptors. (B) Metoclopramide also produces antiemetic effects by inhibition of D2 and 5-HT3 receptors in the CTZ.

CTZ: Chemoreceptor trigger zone; GI: Gastrointestinal.

Adapted from [30].

Actions on emesis

Emesis is a highly organized process that is coordinated by the vomiting center in the CNS and receives input from visceral afferent neurons in the GI tract. In animal models, stimulation of dopamine D2 receptors at the level of the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ), located in the area postrema in the medulla oblongata, has been used to characterize vomiting as well as gastrointestinal motor correlates, including gastric relaxation and commencement of the retrograde giant contraction in the small bowel. Metoclopramide produces its antiemetic effects by inhibition of D2 and 5-HT3 receptors in the chemoreceptor trigger zone (Figure 2B) [36,37].

Indications

Metoclopramide is used for the symptomatic treatment of postoperative or chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, gastro-esophageal reflux disease and gastroparesis. Metoclopramide is generally started at a dose of 5–10 mg orally, 30 min before meals and at bedtime. The dose can be increased up to 20 mg four-times daily if necessary, but may be limited by side effects.

Metoclopramide is available in a liquid preparation for patients for whom there is concern that oral tablets may not be adequately emptied from the stomach to allow sufficient absorption of the medication. Recently, an orally disintegrating sublingual formulation of metoclopramide has been developed and is available for use. An intranasal formulation of metoclopramide is also available and may have advantages including rapid-onset of delivery and circumvention of first-pass elimination compared with oral formulations. Bioavailability was recently demonstrated to be increased with the intranasal compared with the oral formulation of metoclopramide (54.61 vs 40.67%) [38].

Subcutaneous injections of metoclopramide are also available and have been demonstrated to improve symptoms in patients with more refractory symptoms [39]. Finally, intravenous metoclopramide is often used for patients who are hospitalized with exacerbations of gastroparesis.

Clinical efficacy

Metoclopramide is approved for short-term use in diabetic gastroparesis. Five controlled trials and four open-label series [13,40–47] have evaluated the efficacy of metoclopramide in the treatment of diabetic gastroparesis. Symptoms improved in seven studies and gastric emptying was accelerated in five studies. The largest study to date was by Patterson et al., who performed a randomized, double-blind multicenter trial on 45 patients with diabetic gastroparesis to compare the efficacy and safety of domperidone versus metoclopramide. Gastroparesis symptom scores as well as adverse CNS effects were evaluated after 2 and 4 weeks. Metoclopramide improved symptoms by 39% but this was not statistically different from domperidone. However, CNS side effects were more pronounced with metoclopramide [47].

Perkel et al. performed the second-largest trial to date. This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study on 28 subjects with gastroparesis secondary to diabetes (n = 5), owing to post-surgical causes (n = 4) and idiopathic causes (n = 19). Symptom scores, including meal tolerance, epigastric pain, postprandial bloating, heartburn, belching and regurgitation, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and early satiety were evaluated pre-study at weekly intervals and at 4 weeks. Metoclopramide significantly improved the symptoms scores of patients with idiopathic and postsurgical causes of gastroparesis. Overall, symptom scores improved by 29% with metoclopramide, and there was a significantly greater improvement of symptoms scores with metoclopramide compared with placebo (p < 0.05) [42].

Metoclopramide has been demonstrated to be effective for the short-term treatment of gastroparesis for up to several weeks [13,42], but long-term efficacy has not been proven [48]. Longstreth et al. showed prolonged improvement in symptoms, as well as gastric emptying, in one subject over 6 months [41]. Lata et al. reviewed studies from 1965 to 2002 to investigate the efficacy of chronic metoclopramide therapy. No consistent benefit was observed from the use of metoclopramide for more than 1 month. The longest trial was 6 months in duration and showed improvement in only three patients for 1 month or more. However, these were small, uncontrolled, open-label studies that do not provide sufficient data to determine whether chronic metoclopramide improves symptoms [48]. Gastric emptying has also been demonstrated to improve with short-term administration of metoclopramide, but returned to baseline with long-term dosing for more than 1 month [49]. There was also poor correlation between the acceleration of gastric emptying and symptomatic improvement (coefficient of correlation [r] = 0.09 and 0.29 for parenteral and oral metoclopramide, respectively) [45]. However, some patients reported continued symptomatic relief without a prolonged effect on gastric emptying [48]. Thus, symptomatic improvement from metoclopramide may not result entirely from promotility effects, but also from antiemetic effects and potentially from normalization of gastric slow-wave dysrhythmias [50]. Finally, there is some evidence that antidopaminergic agents, specifically domperidone, may modulate visceral hypersensitivity by acting along the brain–gut axis and thus improving pain [51]. Metoclopramide has been demonstrated to improve visceral hypersensitivity in rats, but it is still unclear whether metoclopramide has similar effects in humans [52].

Metoclopramide has been compared in studies with other promotility agents, including cisapride and domperidone. Cisapride showed significantly improved gastric emptying compared with metoclopramide [53]. However, in a double-blind crossover study between metoclopramide and cisapride, there was no significant difference in symptomatic control. There was a trend towards reduced nausea and vomiting with metoclopramide while cisapride showed a trend towards reduced epigastric fullness [54]. Both metoclopramide and cisapride were most effective in reversing the morphine-induced delay in gastric emptying and small intestinal transit in mice compared with domperidone, erythromycin and mosapride [55]. As mentioned previously, metoclopramide was also compared directly with domperidone in a randomized, double-blind multicenter trial. Metoclopramide and domperidone were found to be equally effective in controlling symptoms from diabetic gastroparesis, but CNS side effects were significantly more pronounced with metoclopramide [47].

Adverse effects

Dopamine-containing neurons are found in the substantia nigra, ventral tegmental area and hypothalamic nucleus. Nigrostriatal pathways with initiation, regulation and in the control of movements represent 80% of dopamine-containing neurons in the brain [56,57]. Dopamine-containing neurons from the hypothalamus projecting to the pituitary gland form the tuberoinfundibular pathway and act to suppress prolactin excretion [58].

Most of the side effects from metoclopramide result from its ability to easily cross the blood–brain barrier and are observed in up to 30% of patients [59,60]. Drowsiness, fatigue and lethargy are reported by 10% of patients. Metoclopramide can also worsen underlying depression. Blockade of central D2 receptors may cause extrapyramidal reactions as well as hyperprolactinemia.

Extrapyramidal reactions

Populations most at risk for extrapyramidal reactions include young women, children, the elderly, diabetics, patients with neurologic disorders and patients taking concurrent neuroleptic medications [61,62]. Genetic factors may also play a role as polymorphisms of CYP2DG have been demonstrated to decrease themetabolism of metoclopramide and increase the risk for extrapyramidal reactions [63]. The incidence of these reactions also increases in patients receiving higher intravenous doses. In 479 reports of metoclopramide-related extrapyramidal reactions in the UK from 1967–1982, 455 were for acute dystonias, 20 for parkinsonism and four for TD [64].

Acute dystonic reactions

Acute dystonic reactions are the most frequent extrapyramidal side effects (EPS) from metoclopramide and typically occur within 24–48 h of initiating treatment, thus affecting approximately 0.2–6% of patients taking metoclopramide and the incidence increases with higher doses [64]. Dystonia consists of spasmodic or sustained involuntary muscle contractions resulting in twisting, repetitive movements or abnormal postures. It can present as facial spasm, torticollis, oculogyric crisis, trismus, tortipelvic (abdominal rigidity) or opisthotonic (spasm of the entire body). Acute dystonic reactions typically resolve with discontinuation of the drug [65].

Akithisia

Akithisia presents with subjective feelings of inner restlessness as well as objective findings of motor restlessness. Incidence ranges from 10 to 25% depending on the mode of metoclopramide administration [66,67]. Oral and intramuscular formulations have a lower rate of akithisia compared with intravenous administration. Furthermore, the speed of administration of intravenous metoclopramide also appears to influence the risk of akithisia. In one report, akithisia was reduced from 11.1 to 0% when 10 mg of metoclopramide were administered intravenously over 2 versus 15 min [68].

Drug-induced Parkinsonism

Prolonged therapy with metoclopramide can result in Parkinsonian-like symptoms, including bradykinesia, tremor and rigidity. Incidence is unknown, but one series found a fourfold increased risk of developing drug-induced Parkinsonism in those taking metoclopramide compared with controls [65]. Another series found that patients on metoclopramide had a threefold increased risk of starting anti-Parkinsonian therapy compared with nonusers [69]. Parkinsonian symptoms generally resolve within 2–3 months of discontinuation of metoclopramide.

Tardive dyskinesia

The most feared complication of chronic metoclopramide use is TD, which is characterized by involuntary movements of the face, tongue or extremities. National guidelines [59,70] suggest the prevalence of TD ranges from 1 to 15% after usage of metoclopramide for at least 3 months and may not reverse even after discontinuation of the medication [16,65]. As a result, in 2009, the FDA came out with a black-box warning that must be attached to all metoclopramide labeling, which warns against chronic use except in rare cases. However, a recent review by Rao et al. estimated the risk of TD from metoclopramide use to be less than 1%, much less than the estimated 1–15% suggested by national guidelines [14]. Interestingly, the use of metoclopramide and concurrent rise in metoclopramide-induced TD has been increasing since 2000, which is also the year that Cisapride (Apotex Inc., Ontario, Canada) was withdrawn from the market [16].

Unfortunately, no prospective studies exist to evaluate the risk of TD from metoclopramide use. Available data come from reports by MedWatch (FL, USA) and similar programs in other countries that originate from involuntary movement clinics, prescription databases and case-controlled observational studies (Table 1). One study from the UK looked at 15.9 million prescriptions given between 1967 and 1982 and found 479 reported adverse drug events of extrapyramidal symptoms. Of these, only four were classified as TD, with an incidence far less than 0.1%. However, it is unclear how many of these people were on chronic therapy [64]. A Scandinavian study estimated the incidence of TD owing to metoclopramide to be one in 2000–2800 treatment years [71].

Table 1.

Risk of tardive dyskinesia with metoclopramide.

| Study (year) | Study design | Number studied | Result | Estimated prevalence | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wilholm et al. (1984) | Scandinavian prescription database, 1977–1981 | 11 million Rx of metoclopramide | 37 reports of EPS with 11 TD cases All females, mean age of 76 years | One in 2000–28,000 patient-years, one in 17,800 perscriptions | [71] |

| Bateman et al. (1985) | UK prescription database, 1967–1982 | 15.9 million Rx of metoclopramide | 479 reports of EPS, four with TD | One in ~35,000 prescriptions, significantly higher risk in females, especially those 12–19 years old | [64] |

| Sewell et al. (1992) | Analysis of 67 case reports of metaclopramide- induced TD | 52 patients on at least 30 days of metoclopramide | Mean age of 70 ± 19 years, 3:1 female predominance and Rx duration of 20 ± 15 months; 47% TD cases persisted at 6 months despite discontinuation of metoclopramide | Not estimable | [74] |

| Ganzini et al. (1993) | VA study using exposed/ unexposed design, matched for age, gender, diabetes and comorbidities | 51 chronic Rx of metoclopramide; 51 unexposed | Mean age of 63.9 ± 10.8 years, male predominant, duration of treatment 2.6 ± 2.0 years | 29% TD in metoclopramide Rx vs 17.6% in nonusers (p = 0.08) | [65] |

| Sewell et al. (1994) | VA cross-sectional study | 51 patients with metoclopramide- associated TD; 35 controls matched for age, race, gender and diabetes | Duration of metoclopramide treatment of at least 30 days | 27% TD in metoclopramide Rx vs 12% nonusers (p = 0.08) Patients on metoclopramide and diabetic more likely to develop TD (p = 0.05) | [73] |

| Shafter et al. (2004) | International metoclopramide adverse event reports and US drug-use data | 87 case reports | Mean duration of Rx of 753 ± 951 days; 37% used concomitant drugs, 18% had comorbid diseases with TD risk | Not estimable Increased use of metoclopramide afer cisapride withdrawal | [16] |

| Kenney et al. (2008) | Observational study in a tertiary-care movement- disorder clinic | 434 patients referred for TD | Metoclopramide accounted for 39.4% of TD, the second-leading cause of TD after haloperidol | Not estimable | [72] |

Another series looked retrospectively at 434 patients referred to a movement disorders clinic for TD. All patients had been exposed to a dopamine antagonist for at least 3 months prior to the onset of symptoms. Metoclopramide was second to only haloperidol in inducing TD and was responsible for 39.4% of cases in this series [72].

Ganzini et al. looked at the prevalence of metoclopramide-induced TD in a cohort of 51 patients at a single Veterans Administration hospital on chronic therapy compared with matched controls. They found that 29% of patients on metoclopramide met the criteria for TD compared with 17.6% of controls. The calculated relative risk for developing TD owing to metoclopramide was 1.67 (95% CI: 0.92–2.97) [65]. Sewell et al. looked at a different cohort of 51 patients in a Veterans administration hospital to determine the prevalence of metoclopramide-induced TD. All patients were on metoclopramide for at least 30 days and were compared with 35 matched controls. A total of 27% of metoclopramide users met the criteria for TD as opposed to 12% of controls (p = 0.08). Diabetic patients on metoclopramide had an increased risk for developing TD (p = 0.05) [73].

Finally, Sewell et al. evaluated risk factors for metoclopramide-induced TD in 67 case reports. They found that patients with TD tended to be older (70 ± 10 years), women (3:1 ratio), on higher doses of metoclopramide (mean dose: 32 ± 7 mg) and on a longer duration of treatment (20 ± 15 months). Mean follow-up time was 16 ± 6.5 months and 47% of cases had persistence of TD at 6 months despite discontinuation of the medication [74].

Hyperprolactinemia

Hyperprolactinemia has been associated with metoclopramide and dopamine D2 receptor antagonists with resultant gyneco-mastia, galactorrhea, amenorrhea and impotence. These side effects occur irrespective of the ability of the drug to cross the blood–brain barrier as the pituitary gland lies outside of the barrier. Metoclopramide is a potent stimulator of prolactin release as it blocks dopamine D2 receptors and has been associated with galactorrhea [75]. Hyperprolactinemia and galactorrhea typically occur 3 days to 2 weeks after starting therapy, but have been noted as early as 36 h after initiation of therapy [76,77]. The incidence of hyperprolactinemia and related disorders in a study of 408 patients treated with oral levosulpiride for 4 weeks was 7% in female patients [78]. No studies of hyperprolactinemia with other prokinetics of this size are currently available. Generally, hyperprolactinemia tends to decrease during chronic administration of dopamine antagonists and symptoms typically resolve within 1 week of discontinuation of the medication.

Expert commentary

Prevalence of TD associated with metoclopramide

National guidelines estimate the risk of developing TD from metoclopramide to be 1–15%. Chronic use of metoclopramide certainly appears to increase the risk of developing TD [72]. However, it is currently impossible to calculate the true risk of developing TD from metoclopramide from the current studies available. No prospective studies exist to truly delineate risk. In all but four studies available to date, the number of patients exposed to chronic metoclopramide is unknown, which is essential for determining prevalence [64,65,71,73]. To add to the uncertainty, in two separate Veterans Administration studies, there was no statistically significant difference in the rate of TD in patients on chronic metoclopramide therapy compared with controls [65,73]. One of these studies by Ganzini et al. [65] is referenced by both national guideline positions as the estimate of risk for TD from metoclopramide [59,70].

Increased use of metoclopramide

Usage of metoclopramide has been increasing since 2000, likely because Cisapride was withdrawn from the market at that time and metoclopramide is currently the only medication approved for the treatment of gastroparesis [16]. Whether this will lead to an increased rate of TD from metoclopramide is unknown as all but two of the studies available were published before 2000 [16,72]. Metoclopramide is available in oral, liquid, intranasal and sublingual formulations as well as subcutaneous and intravenous injections. Owing to inconsistent emptying of solid gastric contents, liquid, intranasal and sublingual formulations may lead to more predictable plasma drug levels. Perhaps this will allow physicians to identify the lowest possible dose for patients and lead to a decreased side effect profile.

When to use metoclopramide

Metoclopramide is currently indicated for the treatment of postoperative- or chemotherapy-induced nausea and emesis, gastro-esophageal reflux disease, and gastroparesis. Certainly, with the introduction of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors, there are safer agents available for the treatment of nausea and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Metoclopramide should not be the first-line therapy for these indications. However, in the case of gastroparesis, there are fewer agents available and inadequate treatment of this disease can lead to significant morbidity and mortality [79,80].

Risk stratification

Metoclopramide has been demonstrated to be effective for the short-term treatment of gastroparesis. However, chronic therapy over 3 weeks has not been demonstrated to be effective and is associated with an increased risk for TD. This leads to the clinical paradox that long-term use of metoclopramide has not been demonstrated to be effective and leads to an increased risk of serious adverse events, but unfortunately, no other medical therapies are currently approved for the treatment of gastroparesis.

Therefore, it is important to evaluate the risk/benefit profile before initiating treatment. Risk factors for the development of extrapyramidal reactions include female gender, advanced age, renal insufficiency, cirrhosis, being an alcoholic, being a patient with an underlying movement disorder or those on concurrent neuroleptic medications. Diabetes is also a known risk factor, which further complicates the situation, as diabetes is a risk factor for the development of gastroparesis.

Prior to initiating treatment with metoclopramide, informed consent with the physician, patient, family members and nurse should take place. This should also be documented in the medical chart for medicolegal reasons. Patients should be counseled on the potential side effects of metoclopramide, including potential irreversible effects such as TD, before initiating treatment. Physicians should start with the smallest possible dose and then titrate the medication as needed. Consideration of alternative formulations, such as liquid, sublingual or intranasal forms, may be beneficial in providing more consistent absorption of the medication and may potentially allow for the lowest efficacious dose to be used. Physicians can also consider ‘drug holidays’ to minimize total drug exposure if clinically possible. Patients should also be educated on signs and symptoms of extrapyramidal reactions, especially lip smacking, abnormal movements and facial grimaces, as this may represent early TD. Patients and family members should be instructed to immediately discontinue the drug and notify the physician if they notice any alarming symptoms. Both the patient and physician should be especially vigilant in monitoring for TD, as it may be potentially reversible if recognized early. Refills should be prescribed only by gastrointestinal specialists and healthcare professionals who are trained and educated in monitoring for side effects from metoclopramide. Close follow-up monitoring by the prescribing physician should also be performed while the patient is on metoclopramide as problems may occur if the patient is followed only by the referring physician who may not be as knowledgeable about the potential adverse risks associated with metoclopramide.

Finally, if there is an adverse risk profile, it may be necessary to consider alternative agents, such as domperidone or erythromycin. However, these agents are not approved for use in gastroparesis and domperidone requires an investigational new drug application prior to initiating treatment.

Five-year view

In 5 years’ time, hopefully prospective studies looking into the prevalence of TD from metoclopramide will be available. In addition, potential agents targeting 5-HT4- receptors as well as gastric dysrhythmias will be emerging and comparison with the efficacy and safety of metoclopramide will be evaluated. Other formulations may also prove to have a greater tolerability and increase bioavailability leading to decreased side effects.

Key issues.

Metoclopramide is a dopamine D2 antagonist as well as a 5-HT4 agonist and a weak 5-HT3 antagonist, which leads to the stimulation of gut motility as well as an antiemetic effect.

Metoclopramide easily crosses the blood–brain barrier leading to much of its side effect profile, including extrapyramidal reactions, such as tardive dyskinesia (TD).

Recently, the US FDA has issued a black-box warning regarding long-term usage of metoclopramide, given the potential irreversible nature of TD. National guidelines estimate the prevalence of TD from metoclopramide to be 1–15%. However, no prospective studies exist to calculate actual risk and the actual prevalence may be much lower.

Risk factors for extrapyramidal reactions from metoclopramide include diabetes mellitus. Unfortunately, this is also a risk factor for developing gastroparesis and metoclopramide is the only FDA-approved medication for the treatment of gastroparesis. This leaves physicians and patients in a clinical conundrum. Newer agents with efficacy in improving both short- and long-term symptoms need to be developed and side effect profiles should be examined.

Footnotes

For reprint orders, please contact reprints@expert-reviews.com

Financial & competing interests disclosure

Braden Kuo has received funding from Evoke Pharmaceuticals to carry out clinical trials into the development of intranasal metoclopramide for diabetic gastroparesis. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

• of interest

•• of considerable interest

- 1.Stanghellini V, Tosetti C, Paternico A, et al. Risk indicators of delayed gastric emptying of solids in patients with functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 1996;110(4):1036–1042. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8612991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soykan I, Sivri B, Sarosiek I, Kiernan B, McCallum RW. Demography, clinical characteristics, psychological and abuse profiles, treatment, and long-term follow-up of patients with gastroparesis. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43(11):2398–2404. doi: 10.1023/a:1026665728213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kristensson K, Nordborg C, Olsson Y, Sourander P. Changes in the vagus nerve in diabetes mellitus. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1971;79(6):684–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1971.tb01872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merio R, Festa A, Bergmann H, et al. Slow gastric emptying in Type I diabetes: relation to autonomic and peripheral neuropathy, blood glucose, and glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(3):419–423. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.3.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vinik AI, Ziegler D. Diabetic cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy. Circulation. 2007;115(3):387–397. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.634949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rothstein RD. Gastrointestinal motility disorders in diabetes mellitus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85(7):782–785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanger GJ, Lee K. Hormones of the gut-brain axis as targets for the treatment of upper gastrointestinal disorders. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7(3):241–254. doi: 10.1038/nrd2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forster J, Damjanov I, Lin Z, Sarosiek I, Wetzel P, McCallum R. Absence of the interstitial cells of Cajal in patients with gastroparesis and correlation with clinical findings. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9(1):102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parkman HP, Camilleri M, Farrugia G, et al. Gastroparesis and functional dyspepsia: excerpts from the AGA/ANMS meeting. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22(2):113–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hasler WL. Gastroparesis: symptoms, evaluation, and treatment. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2007;36:619–647. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horowitz M, Fraser R. Disordered gastric motor function in diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1994;37(6):543–551. doi: 10.1007/BF00403371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kong MF, Horowitz M. Gastric emptying in diabetes mellitus: relationship to blood-glucose control. Clin Geriatr Med. 1999;15(2):321–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snape WJ, Jr, Battle WM, Schwartz SS, Braunstein SN, Goldstein HA, Alavi A. Metoclopramide to treat gastroparesis due to diabetes mellitus: a double-blind, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96(4):444–446. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-96-4-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14••.Rao AS, Camilleri M. Review article: metoclopramide and tardive dyskinesia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31(1):11–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04189.x. Although the incidence of tardive dyskinesia from chronic metoclopramide therapy is unknown, it is likely far below the estimated 1–15% cited in national guidelines. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Justin-Besancon L, Laville C. Antiemetic action of metoclopramide with respect to apomorphine and hydergine. CR Seances Soc Biol Fil. 1964;158:723–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaffer D, Butterfield M, Pamer C, Mackey AC. Tardive dyskinesia risks and metoclopramide use before and after U.S. market withdrawal of cisapride. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2004;44(6):661–665. doi: 10.1331/1544345042467191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Desta Z, Wu GM, Morocho AM, Flockhart DA. The gastroprokinetic and antiemetic drug metoclopramide is a substrate and inhibitor of cytochrome P450 2D6. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002;30(3):336–343. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.3.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bateman DN. Clinical pharmacokinetics of metoclopramide. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1983;8(6):523–529. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198308060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magueur E, Hagege H, Attali P, Singlas E, Etienne JP, Taburet AM. Pharmacokinetics of metoclopramide in patients with liver cirrhosis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;31(2):185–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1991.tb05511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bateman DN, Gokal R, Dodd TR, Blain PG. The pharmacokinetics of single doses of metoclopramide in renal failure. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;19(6):437–441. doi: 10.1007/BF00548588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muller DJ, Shinkai T, De Luca V, Kennedy JL. Clinical implications of pharmacogenomics for tardive dyskinesia. Pharmacogenomics J. 2004;4(2):77–87. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shin JG, Soukhova N, Flockhart DA. Effect of antipsychotic drugs on human liver cytochrome P-450 (CYP) isoforms in vitro: preferential inhibition of CYP2D6. Drug Metab Dispos. 1999;27(9):1078–1084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolf CR, Smith G, Smith RL. Science, medicine, and the future: pharmacogenetics. Br J Med. 2000;320(7240):987–990. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7240.987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vella A, Lee JS, Camilleri M, et al. Effects of pramlintide, an amylin analogue, on gastric emptying in Type 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2002;14(2):123–131. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2002.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ratner RE, Dickey R, Fineman M, et al. Amylin replacement with pramlintide as an adjunct to insulin therapy improves long-term glycaemic and weight control in Type 1 diabetes mellitus: a 1-year, randomized controlled trial. Diabet Med. 2004;21(11):1204–1212. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heine RJ, Van Gaal LF, Johns D, Mihm MJ, Widel MH, Brodows RG. Exenatide versus insulin glargine in patients with suboptimally controlled Type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(8):559–569. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-8-200510180-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Talley SJ, Bytzer P, Hammer J, Young L, Jones M, Horowitz M. Psychological distress is linked to gastrointestinal symptoms in diabetes mellitus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(4):1033–1038. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu J, Paine MJ, Marechal JD, et al. In silico prediction of drug binding to CYP2D6: identification of a new metabolite of metoclopramide. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34(8):1386–1392. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.009852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valenzuela JE, Dooley C. Dopamine antagonists in the upper gastrointestinal tract. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1984;96:127–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tonini M, Cipollina L, Poluzzi E, Crema F, Corazza GR, De Ponti F. Review article: clinical implications of enteric and central D2 receptor blockade by antidopaminergic gastrointestinal prokinetics. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19(4):379–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fernandez AG, Massingham R. Peripheral receptor populations involved in the regulation of gastrointestinal motility and the pharmacological actions of metoclopramide-like drugs. Life Sci. 1985;36(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(85)90280-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Albibi R, McCallum RW. Metoclopramide: pharmacology and clinical application. Ann Intern Med. 1983;98(1):86–95. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-98-1-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clarke DE, Craig DA, Fozard JR. The 5-HT4 receptor: naughty, but nice. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1989;10(10):385–386. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(89)90177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dumitrascu DL, Ungureanu O, Verzea D, Pascu O. The effect of metoclopramide on antral emptying of a semisolid meal in patients with functional dyspepsia. A randomized placebo controlled sonographic study. Rom J Intern Med. 1998;36(1–2):97–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kishibayashi N, Karasawa A. Stimulating effects of KW-5092, a novel gastroprokinetic agent, on the gastric emptying, small intestinal propulsion and colonic propulsion in rats. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1995;67(1):45–50. doi: 10.1254/jjp.67.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lang IM, Sarna SK, Condon RE. Gastrointestinal motor correlates of vomiting in the dog: quantification and characterization as an independent phenomenon. Gastroenterology. 1986;90(1):40–47. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(86)90072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitchelson F. Pharmacological agents affecting emesis. A review (part I) Drugs. 1992;43(3):295–315. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199243030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahajan HS, Gattani S. In situ gels of metoclopramide hydrochloride for intranasal delivery: in vitro evaluation and in vivo pharmacokinetic study in rabbits. Drug Deliv. 2010;17(1):19–27. doi: 10.3109/10717540903447194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCallum RW, Valenzuela G, Polepalle S, Spyker D. Subcutaneous metoclopramide in the treatment of symptomatic gastroparesis: clinical efficacy and pharmacokinetics. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;258(1):136–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brownlee M, Kroopf SS. Letter: metoclopramide for gastroparesis diabeticorum. N Engl J Med. 1974;291(23):1257–1258. doi: 10.1056/nejm197412052912321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Longstreth GF, Malagelada JR, Kelly KA. Metoclopramide stimulation of gastric motility and emptying in diabetic gastroparesis. Ann Intern Med. 1977;86(2):195–196. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-86-2-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perkel MS, Moore C, Hersh T, Davidson ED. Metoclopramide therapy in patients with delayed gastric emptying: a randomized, double-blind study. Dig Dis Sci. 1979;24(9):662–666. doi: 10.1007/BF01314461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCallum RW, Ricci DA, Rakatansky H, et al. A multicenter placebo-controlled clinical trial of oral metoclopramide in diabetic gastroparesis. Diabetes Care. 1983;6(5):463–467. doi: 10.2337/diacare.6.5.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loo FD, Palmer DW, Soergel KH, Kalbfleisch JH, Wood CM. Gastric emptying in patients with diabetes mellitus. Gastroenterology. 1984;86(3):485–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ricci DA, Saltzman MB, Meyer C, Callachan C, McCallum RW. Effect of metoclopramide in diabetic gastroparesis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1985;7(1):25–32. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198502000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Erbas T, Varoglu E, Erbas B, Tastekin G, Akalin S. Comparison of metoclopramide and erythromycin in the treatment of diabetic gastroparesis. Diabetes Care. 1993;16(11):1511–1514. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.11.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Patterson D, Abell T, Rothstein R, Koch K, Barnett J. A double-blind multicenter comparison of domperidone and metoclopramide in the treatment of diabetic patients with symptoms of gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(5):1230–1234. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48•.Lata PF, Pigarelli DL. Chronic metoclopramide therapy for diabetic gastroparesis. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37(1):122–126. doi: 10.1345/aph.1C118. Although studies do not show benefit for the long-term use of metoclopramide, many patients with gastroparesis continue to be on long-term therapy given the lack of alternative agents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schade RR, Dugas MC, Lhotsky DM, Gavaler JS, Van Thiel DH. Effect of metoclopramide on gastric liquid emptying in patients with diabetic gastroparesis. Dig Dis Sci. 1985;30(1):10–15. doi: 10.1007/BF01318364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen JD, Pan J, McCallum RW. Clinical significance of gastric myoelectrical dysrhythmias. Dig Dis. 1995;13(5):275–290. doi: 10.1159/000171508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bradette M, Pare P, Douville P, Morin A. Visceral perception in health and functional dyspepsia. Crossover study of gastric distension with placebo and domperidone. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36(1):52–58. doi: 10.1007/BF01300087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Banner SE, Sanger GJ. Differences between 5-HT3 receptor antagonists in modulation of visceral hypersensitivity. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;114(2):558–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rowbotham DJ, Bamber PA, Nimmo WS. Comparison of the effect of cisapride and metoclopramide on morphine-induced delay in gastric emptying. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1988;26(6):741–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1988.tb05313.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Caestecker JS, Ewing DJ, Tothill P, Clarke BF, Heading RC. Evaluation of oral cisapride and metoclopramide in diabetic autonomic neuropathy: an eight-week double-blind crossover study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1989;3(1):69–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1989.tb00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suchitra AD, Dkhar SA, Shewade DG, Shashindran CH. Relative efficacy of some prokinetic drugs in morphine-induced gastrointestinal transit delay in mice. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9(4):779–783. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i4.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kelly J, Alheid GF, McDermott L, Halaris A, Grossman SP. Behavioral and biochemical effects of knife cuts that preferentially interrupt principal afferent and efferent connections of the striatum in the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1977;6(1):31–45. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(77)90157-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Quenzer LF, Galli CL, Neff NH. Activation of the nigrostriatal dopaminergic pathway by injection of cholera enterotoxin into the substantia nigra. Science. 1977;195(4273):78–80. doi: 10.1126/science.831258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ben-Jonathan N, Hnasko R. Dopamine as a prolactin (PRL) inhibitor. Endocr Rev. 2001;22(6):724–763. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.6.0451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Parkman HP, Hasler WL, Fisher RS. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(5):1592–1622. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jolliet P, Nion S, Allain-Veyrac G. Evidence of lowest brain penetration of an antiemetic drug, metopimazine, compared with domperidone, metoclopramide and chlorpromazine, using an in vitro model of the blood–brain barrier. Pharmacol Res. 2007;56(1):11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miller LG, Jankovic J. Metoclopramide-induced movement disorders. Clinical findings with a review of the literature. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149(11):2486–2492. doi: 10.1001/archinte.149.11.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pasricha PJ, Pehlivanov N, Sugumar A, Jankovic J. Drug insight: from disturbed motility to disordered movement – a review of the clinical benefits and medicolegal risks of metoclopramide. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;3(3):138–148. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van der Padt A, van Schaik RH, Sonneveld P. Acute dystonic reaction to metoclopramide in patients carrying homozygous cytochrome P450 2D6 genetic polymorphisms. Neth J Med. 2006;64(5):160–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64••.Bateman DN, Rawlins MD, Simpson JM. Extrapyramidal reactions with metoclopramide. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985;291(6500):930–932. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6500.930. Although the incidence of tardive dyskinesia from chronic metoclopramide therapy is unknown, it is likely far below the estimated 1–15% cited in national guidelines. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ganzini L, Casey DE, Hoffman WF, McCall AL. The prevalence of metoclopramide-induced tardive dyskinesia and acute extrapyramidal movement disorders. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153(12):1469–1475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McCallum RW, Ippoliti AF, Cooney C, Sturdevant RA. A controlled trial of metoclopramide in symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux. N Engl J Med. 1977;296(7):354–357. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197702172960702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jungmann E, Schoffling K. Akathisia and metoclopramide. Lancet. 1982;2(8291):221. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)91077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Regan LA, Hoffman RS, Nelson LS. Slower infusion of metoclopramide decreases the rate of akathisia. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27(4):475–480. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Avorn J, Gurwitz JH, Bohn RL, Mogun H, Monane M, Walker A. Increased incidence of levodopa therapy following metoclopramide use. JAMA. 1995;274(22):1780–1782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abell TL, Bernstein RK, Cutts T, et al. Treatment of gastroparesis: a multidisciplinary clinical review. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18(4):263–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wiholm BE, Mortimer O, Boethius G, Haggstrom JE. Tardive dyskinesia associated with metoclopramide. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984;288(6416):545–547. doi: 10.1136/bmj.288.6416.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kenney C, Hunter C, Davidson A, Jankovic J. Metoclopramide, an increasingly recognized cause of tardive dyskinesia. J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;48(3):379–384. doi: 10.1177/0091270007312258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sewell DD, Kodsi AB, Caligiuri MP, Jeste DV. Metoclopramide and tardive dyskinesia. Biol Psychiatry. 1994;36(9):630–632. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)90077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sewell DD, Jeste DV. Metoclopramide-associated tardive dyskinesia. An analysis of 67 cases. Arch Fam Med. 1992;1(2):271–278. doi: 10.1001/archfami.1.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cooper BT, Mountford RA, McKee C. Galactorrhoea, hyperprolactinaemia, and pituitary adenoma presenting during metoclopramide therapy. Postgrad Med J. 1982;58(679):314–315. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.58.679.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maddern GJ. Galactorrhoea due to domperidone. Med J Aust. 1983;2(11):539–540. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1983.tb122658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kaufman JM, Elewaut A, Vermeulen A. Effect of domperidone on prolactin (PRL) and thyrotrophin (TSH) secretion. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1981;254(2):293–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Corazza GR, Biagi F, Albano O, et al. Levosulpiride in functional dyspepsia: a multicentric, double-blind, controlled trial. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1996;28(6):317–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hyett B, Martinez FJ, Gill BM, et al. Delayed radionucleotide gastric emptying studies predict morbidity in diabetics with symptoms of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(2):445–452. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jung HK, Choung RS, Locke GR, 3rd, et al. The incidence, prevalence, and outcomes of patients with gastroparesis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, from 1996 to 2006. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(4):1225–1233. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]