Summary

Morphogen gradients play fundamental roles in patterning and cell specification during development by eliciting differential transcriptional responses in target cells. In Drosophila, Decapentaplegic (Dpp), the BMP2/4 homolog, downregulates transcription of the nuclear repressor brinker (brk) in a concentration-dependent manner to generate an inverse graded distribution. Both Dpp and Brk are critical for directing Dpp target gene expression in defined domains and the consequent execution of distinct developmental programs. Thus determining the mechanism by which the brk promoter interprets the Dpp activity gradient is essential for understanding both Dpp-dependent patterning, and how graded signaling activity can generate different responses through transcriptional repression. We have uncovered key features of the brk promoter that suggest it uses a complex enhancer logic not represented in current models. First, we find that the regulatory region contains multiple compact modules that can independently drive brk-like expression patterns. Second, each module contains binding sites for the Schnurri/Mad/Medea (SMM) complex, which mediates Dpp-dependent repression, linked to regions that direct activation. Third, the SMM repression complex acts through a distance-dependant mechanism that likely uses the canonical co-repressor C-terminal Binding Protein (CtBP). Finally, our data suggest that inputs from multiple regulatory modules are integrated to generate the final pattern. This unusual promoter organization may be necessary for brk to respond to the Dpp gradient in a precise and robust fashion.

Keywords: morphogen, developmental patterning, transcriptional regulation, decapentaplegic, brinker

Introduction

Dpp, the Drosophila homolog of vertebrate Bone Morphogenetic Protein BMP2/4, plays a vital role in patterning embryonic and larval structures. A gradient of BMP signaling is essential for specifying cell fates throughout the dorsal region of the embryo, while later in embryogenesis Dpp acts more locally to induce specific cell fates or tissues. During larval development, Dpp regulates growth and patterning in the imaginal discs. In the wing disc, a gradient of Dpp activity centered on the anterior-posterior (A/P) compartment boundary controls cell fate, proliferation and survival. In adults Dpp acts as a juxtacrine signal to maintain stem cell fates in the male and female germline (Parker et al., 2004; Raftery and Sutherland, 1999; Segal and Gelbart, 1985).

Dpp signaling is initiated by binding of the ligand to a complex of the type-I and type-II serine/threonine kinase receptors, Thickveins (Tkv) and Punt (Put), respectively. Activated Tkv phosphorylates the BMP-specific Smad, Mothers against dpp (Mad), leading to its association with the co-Smad Medea (Med) and accumulation of the Mad/Med complex in the nucleus. Mad and Med binding sites have been found in the promoters of many Dpp-responsive genes. However two other transcription factors, Brinker (Brk) and Schnurri (Shn), also play essential roles in the regulation of most Dpp targets. Brk binds to the enhancers of Dpp target genes and functions as a constitutive repressor (Kirkpatrick et al., 2001; Rushlow et al., 2001; Saller and Bienz, 2001). Shn, a conserved protein with multiple zinc-finger DNA-binding domains, represses brk in regions where Dpp signaling is present (Marty et al., 2000; Torres-Vazquez et al., 2001). This repression is mediated by a Shn/Mad/Med (SMM) complex that antagonizes transcriptional activation by binding to a GRCGNC(N5)GTCTG motif (Gao and Laughon, 2006; Gao et al., 2005; Muller et al., 2003; Pyrowolakis et al., 2004). Thus Dpp regulates its target genes through two mechanisms: directly by activating gene expression, and indirectly by Shn-dependent repression of Brk.

Repression by Dpp results in an inverse gradient of Brk throughout development. Inputs from both Dpp and Brk are required for regulating growth and apoptosis and establishing the distinct thresholds that direct target gene expression in defined domains (Moser and Campbell, 2005; Muller et al., 2003). The contribution of brk to delimiting regions of gene expression has been best demonstrated for spalt (sal) and optomotor blind (omb), which are expressed in domains of high and low Dpp activity respectively, and are differentially sensitive to repression by ectopic Brk (Jazwinska et al., 1999; Moser and Campbell, 2005; Muller et al., 2003). These essential roles for Brk underscore the importance of understanding the mechanism through which the Dpp gradient is interpreted to generate a graded brk expression pattern. The complex and dynamic expression pattern of dpp throughout development is mediated by multiple tissue and stage-specific enhancers distributed over ~50 kb (St Johnston et al., 1990; Stultz et al., 2006). In contrast, the similarly dynamic brk pattern results from two simple inputs – ubiquitous activation and spatially restricted Dpp-dependent repression mediated by the SMM complex (Muller et al., 2003). This work identified only a single region within the brk promoter which drives ubiquitous activation, and three repression elements that mapped as far as 3 kb away, suggesting a model in which SMM complexes act at long range to counteract activation.

Contrary to this model, we show that the brk promoter uses a much more intricate enhancer logic. We demonstrate that the 16 kb brk regulatory region harbors multiple modular elements along its length, each of which can independently drive a brk-like expression pattern. Analysis of individual modules reveals that they contain SMM sites closely linked to sequences that mediate activation. We show that the SMM complex represses adjacent activators through a distance-dependent mechanism that enables each module to respond autonomously to Dpp signaling. Thus in the brk promoter, multiple SMM sites individually interpret the Dpp gradient and combined outputs from multiple modules generate the endogenous brk pattern. This unique architecture may be required to produce a robust and precise response to Dpp signaling.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila strains and genetics

shn4738 and brkX47 have been described (Arora et al., 1995; Campbell and Tomlinson, 1999). en-Gal4>UAS-TkvA embryos were maintained at 18°C and shifted to 25°C at first instar. For shn4738 rescue, embryos received two 1 hour heat shocks at 37°C separated by 25°C rest periods (Yao et al., 2006). Homozygous mutants were identified by the absence of marked balancers. Embryo extracts from Myc-tagged UAS-ShnCT and UAS-ShnCTM lines were used to monitor expression by probing Western blots with anti-Myc antisera (9E10, Santa Cruz) and re-probing with anti-ßtubulin to confirm equivalent loading.

Promoter analysis and histochemistry

Fragments L3, L6, L7, L13 and L13M3, L13M4, L13M7/8/9 and L13M3+M7/8/9 were cloned into C4PLZ (Wharton and Crews, 1993), while pCasPerhs43βgal (Thummel et al., 1988) was used for all other inserts. The eGFP coding region, which does not block long range repression (Barolo and Levine, 1997), was used as spacer DNA in L12+Spacer and multimerized module reporters. Multimerized modules were generated from L12 by sequential insertion of 180 bp spacers and additional modules in the same orientation with respect to the lacZ transcriptional start. The L12 SMM site lies at +97 bp from the 5’ end, and insertion of the 180 bp spacer ensures that each SMM site is separated by 768 bp. The endpoints of fragments amplified to demonstrate the presence of modules in vivo are: module-3 -2608/-3188, module-4 -4864/5634, module-5 -6217/6990, module-7/8/9 -7798/8581, module-10 -13467/14212. Mutant constructs were generated using PCR and standard molecular techniques.

Embryos and imaginal discs were stained (Torres-Vazquez et al., 2000) or visualized by fluorescence microscopy using mouse anti-ßgal and goat anti-rabbit-Alexa488 antibodies (Molecular Probes). omb-Gal4>UAS-eGFP expression was visualized directly. Except in Fig. 5, reporter expression is from homozygous transgenic lines. Multiple lines were tested for each construct.

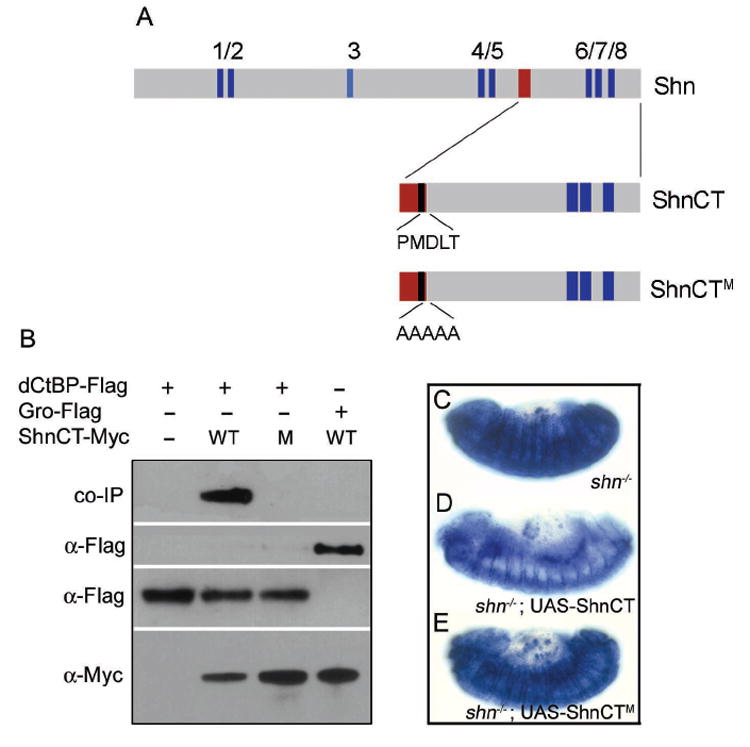

Figure 5. Shn interacts with the short-range co-repressor dCtBP.

(A) Full length Shn and ShnCT, a polypeptide sufficient for Dpp-dependent repression of brk, are shown. Zinc finger domains are marked in blue. An ~100 residue domain required for repression (red bar) includes a CtBP interaction motif PMDLT, that was mutated in ShnCTM as shown. (B) ShnCT interacts with dCtBP but not Gro. Extracts from S2 cells transfected as indicated, were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc and probed with anti-Flag. Expression levels were monitored by probing separate blots with anti-Flag or anti-Myc. Wildtype ShnCT bound dCtBP but not Gro, while ShnCTM failed to interact with dCtBP. (C-E) The CtBP interaction motif contributes to repression in vivo. (C) The brkX47 reporter is expressed ubiquitously in shn- embryos. (D) In shn- embryos Hsp70-Gal4 driven expression of ShnCT restores brk-LacZ repression in the dorso-lateral ectoderm and rescues dorsal closure defects. (E) ShnCTM is unable either to repress brk-LacZ or rescue the shn- morphology.

Identification of SMM motifs

Potential SMM sites in brk regions of D. melanogaster, D. pseudoobscura and D. virilis, were identified by searching with MERmaid (http://opengenomics.org/mermaid) for close matches to the SMM consensus GRCGNC(N5)GTCTG (Pyrowolakis et al., 2004). D. melanogaster contains nine perfect matches and two sites that diverge at one nucleotide (#3 GCGCC(N5)GTCTG at -3,097 and #1 GTCGTC(N5)GTCTG at -271 bps). Reporters (L1 and L12) containing these and other divergent sites (Yao et al., 2006) are functional in vivo, suggesting a modified consensus of GNCKNC(N5)GTCTG (K=G/T). SMM sites matching this consensus were identified in the Anopheles gambiae promoter using Fly Enhancer (http://genomeenhancer.org/fly) (Markstein et al., 2002).

Biochemical assays

Co-repressor constructs for S2 cell expression were obtained from David Arnosti (dCtBP-2xFlag) and Albert Courey (Flag-Groucho). ShnCT sequences (residues 1892-2529; (Gao et al., 2005) were subcloned into pAWM, containing an Actin5C promoter and C-terminal 6XMyc epitopes (a gift from T. D. Murphy). ShnCTM was generated by PCR mutagenesis. Whole-cell extracts from S2 cells transfected with ShnCT or ShnCTM and dCtBP or Gro were incubated with anti-Myc antisera and the immunoprecipitates run on 4-12% gradient SDS-polyacrylamide gels followed by visualization of interacting protein with anti-Flag antisera (M2, Sigma).

In vitro DNA binding assays

Gel shift and supershift assays were performed as described (Yao et al., 2006). In competition experiments excess unlabelled probes were used at 100X (GST-Med) or 500X (GST-Mad). The wildtype sequence 5’-TTCAAACGCAGACAGCGCGGCGGAGCGTCGA-3’ contains an SMM site (bold) that was abolished in the mutant oligo 5’-TTCAAACGactcaAGCGCttattaAGCGTCGA-3’.

Results

The brk promoter contains multiple activator elements

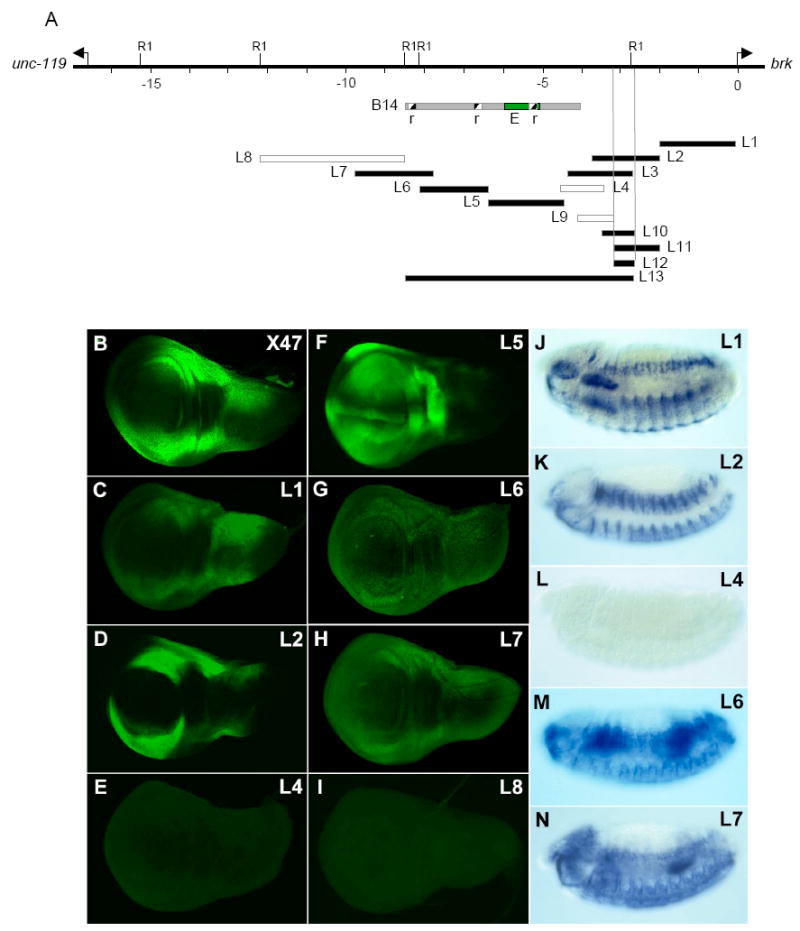

To analyze the cis-regulatory properties of the brk promoter, we generated transgenic ß-gal reporter lines containing a series of partially overlapping fragments spanning ~12 kb upstream of the coding region (Fig. 1). Reporters derived from at least four separate regions directed expression in the wing disc in a pattern resembling endogenous brk, i.e., low to no expression medially where Dpp is transcribed along the A/P boundary, and high levels laterally where Dpp signaling is absent (Campbell and Tomlinson, 1999; Jazwinska et al., 1999; Minami et al., 1999). These four regions correspond to fragments L1, L2/L3, L5/L6, and L6/L7 (Fig. 1A). The patterns driven by individual fragments, while similar, were not identical, and could be distinguished based on the level of expression and the extent of repression in the center of the disc. Fragment L1 drove expression at extremely low levels relative to a control brkX47 enhancer trap that mimics the endogenous brk expression pattern (Campbell and Tomlinson, 1999), (Fig. 1B, C; see legend for details). The adjacent overlapping fragments L2 and L3 resolved similar patterns but were transcribed at high levels compared to L1 (Fig. 1D, data not shown). Fragment L5 drove strong expression and was excluded from only a narrow region along the A/P boundary (Fig. 1F). Reporters L6 and L7 differed in the width of their expression domains relative to brkX47 and each other (Fig. 1G, H); additionally L6 was much weaker (see legend). Not all promoter regions drove patterned expression; two transgenes L4 and L8 were inactive (Fig. 1E, I). All fragments that directed brk-like patterns in the wing disc also drove expression in stage 11 and older embryos in regions where endogenous brk is detected, suggesting that the regulatory elements are not tissue or stage-specific (Fig. 1J, K and M, N). Fragment L4, which was inert in the disc, showed no embryonic expression (Fig. 1L). Prior to stage 11 brk expression is directly activated by the Dorsal morphogen through sites contained in L8 (Markstein et al., 2002). Consistent with this, the L8 reporter that was inactive in the disc drove embryonic expression prior to stage 11 (data not shown).

Figure 1. The brk regulatory region contains multiple elements that mediate activation.

(A) The brk promoter with arrows indicating transcription start sites for brk and unc-119. Scale is in kb and EcoR1 sites (R1) are marked. Filled fragments drive expression in wing discs and embryos after stage 11; open fragments are transcriptionally inactive at these stages. The B14 construct of Muller et al. (2003) is in gray, with ‘r’ signifying repressor elements and E the activator. (B-I) Reporter expression in wing discs oriented anterior up, ventral left. (B) The brkX47 enhancer trap reproduces wildtype brk pattern. (C-D) L1 and L2 are non-overlapping promoter fragments that direct patterns resembling endogenous brk. L1 drives low-level expression and the image was enhanced by increased exposure time. (E) L4 does not display detectable expression. (F) L5 is expressed strongly and excluded from only a narrow central domain. The central stripe of expression corresponds to the A/P compartment boundary where pMad levels are reduced (Tanimoto et al., 2000). (G-H) L6 and L7 also drive laterally restricted expression. L6 directs expression at lower levels than L7, and was enhanced by increasing exposure time. (I) Expression of L8 cannot be detected. (J-N) Reporter expression in late stage 12/13 embryos, oriented laterally. (J-K) Both L1 and L2 reporters mimic brk expression in ventral and lateral stripes in the ectoderm. (L) No embryonic expression is detected with L4. (M-N) L6 and L7 reporters can be detected in a brk-like pattern in the ectoderm and midgut.

The unexpected finding that several non-overlapping fragments drive patterned expression indicates that, at a minimum, the brk promoter contains four independent activator elements. These results are in striking contrast to a previous study (based on analysis of a nested deletion series), which concluded that the brk pattern results from a balance between activation mediated through a single region that maps between -5 and -6 kb (E1), and Dpp-dependent repression mediated through three ‘silencer’ elements (r) located 0.2 to 3 kb away (Muller et al., 2003; see Fig. 1A).

A compact brk promoter element contains closely linked but separable sites mediating activation and repression

We next chose to delineate one cis-regulatory unit and study its composition and mechanism of regulation. We focused on the region of overlap between fragments L2 and L3. Analysis of three additional overlapping fragments (L9-L11) identified a region between the proximal end of L10 and the distal end of L11 that was critical for expression (see Fig. 1A). A construct containing these 580 bases (L12) drove a brk-like expression pattern in both wing discs and embryos (Fig. 2A, B). To establish that the L12 reporter was Dpp-responsive, we expressed a constitutively activated Tkv receptor (TkvA) in the posterior compartment of the wing disc using the en-Gal4 driver. Ectopic activation of the Dpp pathway resulted in down regulation of reporter activity (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, the reporter was ubiquitously expressed in embryos mutant for shn, which is essential for Dpp-dependent repression (Fig. 2D). These results argue that the pattern driven by L12 is generated by repression of a ubiquitous activator in response to Dpp signaling.

Figure 2. A compact promoter fragment is sufficient to generate a brk-like pattern.

A 580 bp fragment (L12) located ~3 kb upstream of the transcription start drives expression in (A) wing discs, and (B) embryos. (C) Up-regulation of Dpp signaling by expression of TkvA using en-Gal4, results in repression of the L12 reporter in the posterior compartment. (D) L12 is derepressed in shn- embryos.

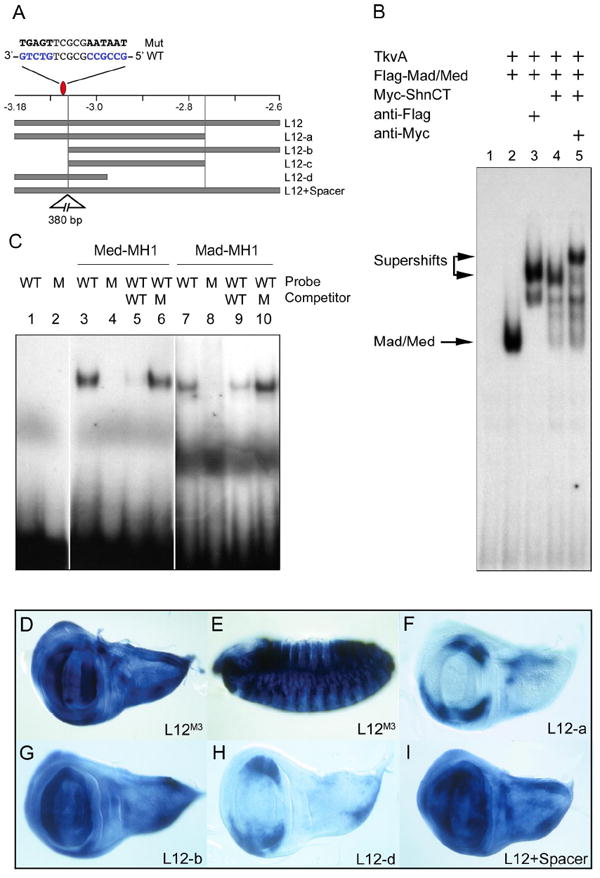

The L12 reporter could contain either a composite activator/repressor element or separable activator and repressor sites that generate a brk-like pattern through a balance of their activities. Previous analysis of the brk promoter has shown that a GRCGNC(N5)GTCTG motif at -8.2 kb (silencer S) can assemble a Shn/Mad/Med complex and mediate transcriptional repression in response to Dpp signaling (Pyrowolakis et al., 2004). The GRCGNC sequence is bound by Mad while Med binds GTCTG, and the 5-nucleotide spacer is critical for recruitment of Shn to the complex (Gao et al., 2005; Pyrowolakis et al., 2004). We identified a single SMM site within L12 that diverges from the consensus at the second position (C rather than A/G, Fig. 3A). We tested whether this non-canonical motif in L12 could assemble a Shn/Mad/Med complex using gel-shift assays. Nuclear extracts from S2 cells transfected with Mad/Med or Shn/Mad/Med were incubated with oligos containing the L12 motif. Incubation with Mad/Med produced a slower migrating complex that was further retarded in the presence of Shn. Incubation with antibodies against epitope tags on Shn, Mad or Med resulted in supershifts, demonstrating that despite the divergent nucleotide, these proteins can form a complex at this site (Fig. 3B). We introduced mutations in the Mad and Med sites that disrupt binding by both proteins (Fig. 3C). A reporter containing the mutated Mad/Med sites (L12M3) was ubiquitously expressed in both wing discs and embryos, demonstrating that the SMM motif in L12 is critical for repression in vivo (Fig. 3D, E).

Figure 3. A modular promoter element contains closely linked sites that mediate activation and Dpp-dependent repression.

(A) Schematic showing L12 and derivatives. The red oval marks the SMM site containing C rather than A/G at position 2. The triangle in L12+Spacer marks the location of the insert. (B) Lysates from S2 cells transfected as indicated, were used to gel-shift an oligo containing the SMM site. Lane-1 contains probe alone. The presence of Mad/Med results in a slower mobility complex (lane-2) that is further retarded by anti-Flag (lane-3) or Myc-ShnCT (lane-4). The Shn/Mad/Med complex is supershifted by incubation with anti-Myc (lane-5). (C) Wildtype (WT) or mutant (M) SMM oligos were incubated with GST-Mad or Med. Both proteins bind wildtype (lanes 3, 7) but not the mutant site (lanes 4, 8). Excess wildtype (lanes 5, 9), but not mutant oligos (lanes 6, 10), block Mad/Med binding. L12M containing the mutant SMM site is ubiquitously expressed in (D) wing discs, and (E) embryos. (F-I) Expression patterns of L12 derivatives in wing discs. (F) L12-a drives laterally restricted expression. (G) L12-b lacking the SMM site is derepressed medially. (H) A 187 bp L12-d fragment drives brk-like expression indicating the presence of closely linked SMM and activator sites. (I) Insertion of a 380 bp spacer between the SMM site and activator sequences (L12+Spacer) results in broad expression.

Next we generated a series of constructs to localize the sequences required for activation. A fragment lacking 161 nucleotides from the 3’ end (L12-a) drove expression in a pattern similar to L12, indicating that all sequences necessary for resolving pattern are present within this minimal fragment (Fig. 3F, compare with Fig. 2A). In contrast, deletion of 119 nucleotides from the 5’ end (L12-b and L12-c) resulted in ubiquitous expression in discs and embryos, consistent with the elimination of the SMM site at -3.1 kb (Fig. 3G, data not shown). Thus sequences mediating activation lie within the central 303 bp region. Furthermore, a 5’ fragment containing only 187 nucleotides (L12-d) also directed a brk-like pattern in the wing disc, indicating that it retains most of the sequences required for activator function (Fig. 3H). In conclusion, the L12 fragment contains a compact module in which separable but adjacent elements that direct ubiquitous expression and Dpp-dependent repression.

SMM-mediated repression is distance dependent

Transcriptional repression is thought to occur through at least four distinct mechanisms – inhibition of the basal machinery at the core promoter (silencing or direct repression), competition between activators and repressors for overlapping or shared binding sites (competition), recruitment of co-repressors that act over distances of 50–150 bases (short-range repression), or enlistment of a distinct set of co-repressors effective over distances of a kb or more (long-range repression) (reviewed in Arnosti, 2002; Courey and Jia, 2001). The initial characterization of the SMM site in silencer S suggested that it functions at long-range to repress an activator located ~3 kb away (Muller et al., 2003). However the proximity of sequences required for activation and repression in L12 suggested that repression by the SMM complex may be distance-sensitive. To investigate this possibility, we increased the spacing between the SMM site and sequences necessary for activation and examined whether reporter expression was altered. Insertion of a 380 bp neutral spacer adjacent to the SMM site in L12 resulted in widespread derepression throughout the wing pouch and the embryo (Fig. 3A, I and data not shown). These results indicate that the SMM complex uses a distance-sensitive, rather than a long-range mechanism for repression.

The brk promoter contains multiple modular enhancers

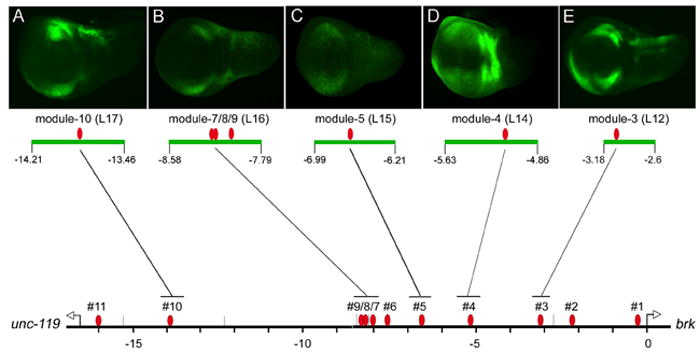

If the SMM complex is only effective at repressing closely linked activators, we reasoned that other functional SMM sites should also be associated with activator binding sites. Since our promoter analysis detected multiple fragments capable of mediating activation independently (see Figs. 1, 2), we searched the regulatory region to determine if additional SMM motifs were located in transcriptionally active fragments. We found eleven sites (nine perfect matches and two that diverge at a single base) within 16 kb upstream of the transcription start site (Fig. 4, and Materials and Methods). Remarkably, every fragment that drove a brk-like expression pattern (L1-L3, L5, L6 and L7) contained one or more SMM sites (see Fig. 1A). Conversely, fragments that lacked activator function (L4, L8 and L9) contained no SMM motifs, reinforcing the idea that repression and activation elements are closely linked. To test this hypothesis directly, we generated reporters containing selected SMM sites flanked by ~380 bp on either side, and examined whether they drove patterned expression (Fig. 4). We chose SMM sites #4, #5, and the #7/8/9 cluster, since regions containing these sites have been implicated in repression (Muller et al., 2003; Pyrowolakis et al., 2004, see r sites in Fig. 1A); and site #10 because it is located near the brkX47 enhancer trap insertion at ~-14.0 kb (Campbell and Tomlinson, 1999). No activators have been mapped adjacent to site #5 and #7/8/9, providing a stringent test for the idea that SMM motifs and activation sequences are linked. Although site #4 is located within a 1 kb region (E1) required for activation (Muller et al., 2003), it has not been established whether the activator and SMM sequences are closely linked.

Figure 4. The brk promoter contains multiple modular regulatory elements.

(A-E) Transgenic reporters containing ~780 bp fragments (green bars), centered on SMM sites, drive brk-like expression patterns in the wing disc. Red ovals mark the location of 11 predicted SMM sites (#1-11) within the brk promoter at -271, -2,165, -3,097, -5,175, -6,627, -7,653, -8,023, -8,174, -8,206, -13,833, and -15,983 bps. (A-D) Expression patterns derived from fragments L17, L16, L15, L14 containing modules-10, 7/8/9, 5, and 4, respectively. Module-4 drives the highest levels of expression laterally. Module-5 drives weak expression, and the image enhanced by increasing exposure time. (E) Module-3 (L12) shown for comparison.

Strikingly, in all four cases, transgenic reporters containing SMM sites flanked by 380 bp on either side drove a ‘lateral on - medial off’ expression pattern in the wing disc (Fig. 4A-D). Thus, along with the enhancer elements identified in L12 (module-3; Fig. 4E), these data identify five separate examples, where activator elements and SMM sites are closely linked to form compact regulatory modules. The expression patterns generated by individual modules share common features, but differ considerably in their level of expression and domain of repression. For instance, module-4 shows only minimal repression along the A/P boundary, compared to module-7/8/9, which contains three SMM sites and shows the broadest region of repression. Importantly, we find that the expression profiles of large fragments that contain a single module correspond closely with the pattern derived from the module itself (e.g., L5 and module-4, L7 and module-7/8/9; see Fig. 1). These similarities suggest that the critical cis-elements responsible for the pattern are contained within the cognate module. In conclusion, these results establish that the brk promoter contains multiple discrete, compact regulatory modules, each of which can individually drive expression in a brk-like pattern.

The short-range co-repressor dCtBP contributes to SMM repression activity

We have shown that repression of adjacent activators in individual modules by the Shn/Mad/Med complex has a limited range. The ability of transcription factors to repress at short or long-range has been proposed to depend on their interaction with different classes of co-repressors. Drosophila C-terminal Binding Protein (dCtBP), a paradigmatic example of a short-range co-repressor, has been implicated in repression by the transcription factors Giant, Kruppel, Knirps and Snail (Arnosti et al., 1996; Hewitt et al., 1999; Keller et al., 2000). Analysis of the Shn sequence revealed that residues 1981-1985 (PMDLT; Fig. 5A) resemble the consensus CtBP interaction motif PX(D/N)LS (Aihara, 2006; Chinnadurai, 2002). This motif maps within a minimal Shn polypeptide (ShnCT, 1892-2529) that can complex with Mad/Med and repress brk transcription in vivo (Gao et al., 2005; Pyrowolakis et al., 2004). To determine if Shn can recruit dCtBP, we tested its ability to form a complex in S2 cells. We observed a strong interaction between dCtBP and ShnCT (Fig. 5B). A mutated ShnCTM protein in which the PMDLT motif was replaced with Ala residues, failed to associate with dCtBP, demonstrating that this sequence is required for interaction. In control experiments, ShnCT failed to co-immunoprecipitate with the long-range co-repressor Groucho (Gro), consistent with the inability of the SMM complex to repress adjacent activators at long range (Fig. 5B).

We next examined the requirement for dCtBP in Shn-mediated brk repression in vivo. Ubiquitously expressed wild type and mutant UAS-ShnCT transgenes were assayed for their ability to repress a brk reporter in shn- embryos. ShnCT repressed brk-LacZ in 74% of mutant embryos (Fig. 5C, D, n=140). In contrast, ShnCTM, which lacks the dCtBP interaction motif, repressed brk-LacZ in only 16% of shn- embryos (Fig. 5E, n=164). Equivalent levels of wildtype and mutant protein were detected on western blots of transgenic embryos (data not shown). Taken together, these data argue that interaction between Shn and dCtBP is biologically relevant, and that dCtBP contributes to the repressive function of the SMM complex in vivo.

The brk promoter integrates outputs from multiple modules

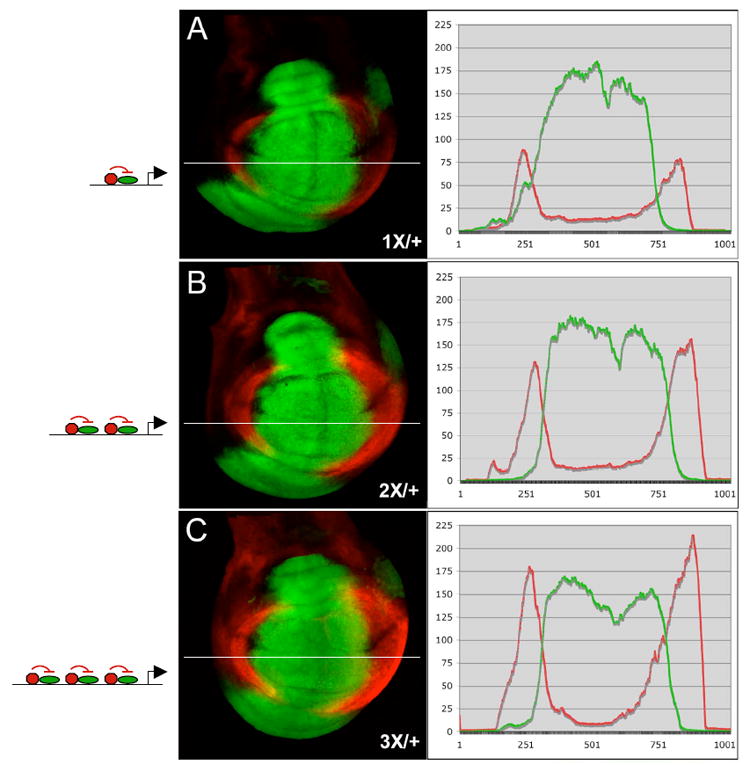

To gain insight into the logic of the multi-modular brk promoter architecture, we first examined the effects of changes in module copy number on the amplitude and spatial domain of reporter gene expression. Simplified promoters were constructed containing 1, 2 or 3 copies of module-3 (1X, 2X and 3X) with spacers to separate individual SMM sites by ~700 bp. The patterns driven by these LacZ reporters in wing discs were examined using omb>GFP expression to aid in comparison across samples (Fig. 6A-C). Confocal analysis of the intensity profile of the ß-gal and GFP channels revealed that reporter expression levels in lateral regions of the disc increased with the number of modules. Interestingly, the domain of Dpp-dependent repression (i.e., sensitivity to Dpp activity) did not appear to change significantly with increased copy number, at least over a three-fold range. These results suggest that one consequence of multiple modules in the endogenous brk promoter could be to help boost expression in lateral regions of the disc where Dpp signaling is absent.

Figure 6. The brk promoter integrates inputs from multiple modules.

Confocal images of wing discs (dorsal up, anterior left) showing reporter-LacZ (red) and omb-Gal4>UAS-eGFP expression (green). The module number and organization (green oval represents activator, red the SMM complex) is depicted schematically. Discs in (A-C) were stained in parallel and visualized using identical settings. Graphs show signal intensity in the red and green channels, measured at the white bar. (A) A 1X/+ reporter containing a single copy of module-3 (L12) was expressed in the wing pouch region lateral to omb>GFP. (B) The 2X/+ and (C) 3X/+ reporter drive increasingly higher levels of expression, but showed no significant overlap with omb>GFP.

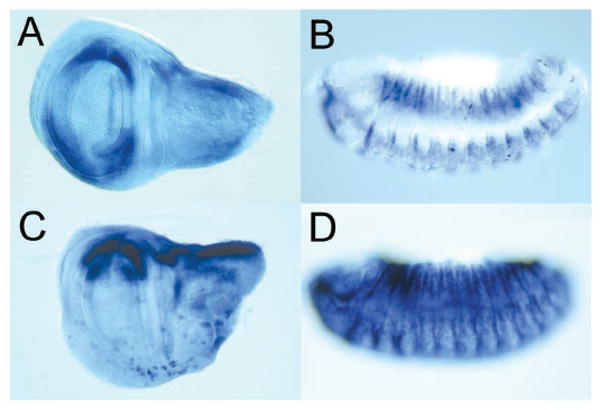

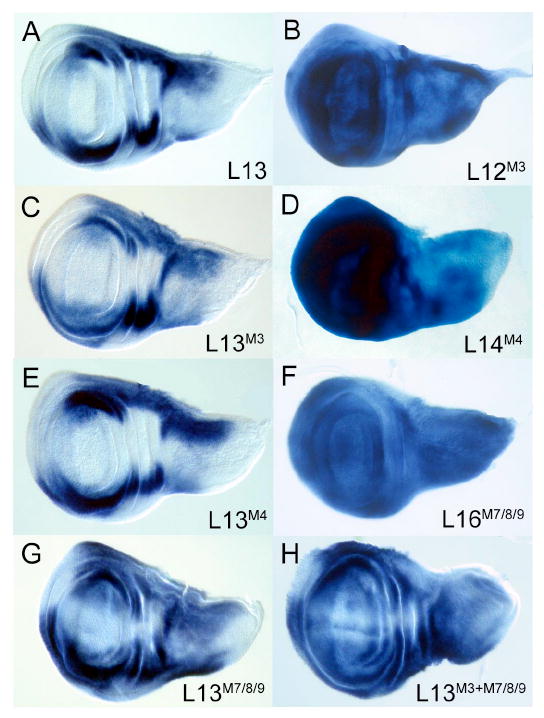

The modules characterized in this study drive patterns that are similar but not identical to each other and endogenous brk. To explore how these distinct patterns are integrated, we examined how a Dpp-insensitive (derepressed) module affects the transcriptional output of a larger promoter fragment that also contains several intact modules. We reasoned that if each module contributes independently to the final pattern, the mutant module lacking an SMM site should activate expression in the center of the disc, similar to the derepression it enables as an isolated module. For these experiments we used the L13 fragment (-8.3 to -2.7 kb; see Fig. 1A) that contains at least four modules (module-3, -4, -5, and -7/8/9). The wildtype L13 reporter drives expression in a pattern closely resembling endogenous brk (Fig. 7A). As shown previously, mutation of the lone SMM site in module-3 (L12M3) resulted in loss of Dpp-responsiveness and widespread activation throughout the wing pouch (Fig. 7B). We generated the identical lesion in L13. Surprisingly, the mutant reporter (L13M3) showed no expression in the medial region of the wing disc where Dpp activity is high (Fig. 7C). Double labeling with omb>GFP showed that the lateral domains of expression were slightly derepressed (Fig. S1). The absence of medial derepression in L13M3 is not due to the fortuitous presence of sequences immediately distal to L12, that act redundantly with the SMM site in module 3, since the same mutation in a larger fragment that contains 511 bp of additional sequence distal to the SMM site (L10M3) also results in ubiquitous expression similar to L12M3 (Fig. S2). These results reveal that in a multi-modular promoter, the presence of wildtype Dpp-sensitive modules can significantly ‘buffer’ the impact of a mutant module in regions of high Dpp signaling.

Figure 7. The impact of Dpp-insensitive mutant modules is ameliorated in multimodular brk reporters.

Wing discs stained for LacZ to visualize reporter expression. (A) Wildtype L13 reporter. (B, D, F) In fragments containing individual modules (see Fig. 4 for nomenclature; mutant modules indicated in superscript) disruption of SMM sites results in expression throughout the wing pouch. (C, E, G) In contrast multimodular L13 reporters containing the same lesions do not show derepression in the medial region (compare with B, D, F, respectively). (H) L13M3+M7/8/9 that contains two mutant modules shows significant expansion of lateral expression but continues to be repressed medially, where Dpp activity is highest. The narrow central stripe of expression corresponds to the A/P boundary where pMad levels are lower (Tanimoto et al., 2000).

To determine whether other Dpp-insensitive modules in the brk promoter are susceptible to buffering, we analyzed reporters in which SMM sites in two other modules (module-4 and module-7/8/9) were mutated in the context of the larger L13 fragment. We first examined the effects of the mutations in isolation (L14M4 and L16M7/8/9, respectively). In both cases ubiquitous activation was observed throughout the central region of the disc (Fig. 7D, F). In contrast, the presence of a mutated module-4 in L13 (L13M4) did not result in upregulation of expression in the center of the disc, similar to the buffering seen with L13M3 (Fig. 7E). Likewise, the L13M7/8/9 reporter was also repressed medially in regions of high Dpp signaling, although significant derepression was seen laterally (Fig. 7G). L13M7/8/9 which lacked three SMM sites, showed more pronounced derepression compared to L13M3 with a single mutant SMM site. We also assayed reporters in which more than one module was disrupted (L13M3+M7/8/9). Remarkably, despite stronger derepression in lateral regions, expression of this transgene was still not detected near the A/P boundary, indicating that the remaining Dpp-sensitive modules retained the ability to override the effects of the mutant modules, albeit in a narrow central domain (Fig. 7H).

Thus although each module is capable of generating an expression pattern independently, the endogenous pattern does not result from mere superimposition of modular inputs. Instead, in the context of a multi-modular promoter, wildtype repressed modules appear to override the contribution of individual ‘derepressed’ modules thus buffering their effect in regions of high Dpp signaling.

Discussion

The brk promoter contains multiple enhancer modules

The brk gene is unique in that eleven SMM sites are present in its regulatory region: no other locus in the genome has more than three sites. These sites are widely dispersed over 16 kb and separated from each other by 0.35 to 5.5 kb, with the exception of sites 7/8/9 which are clustered in a 183 bp region (see Fig. 4). We have shown that for seven of the eleven SMM sites (3, 4, 5, 7/8/9 and 10), sequences that mediate transcriptional activation are located within ~380 bp of the SMM sites. These SMM sites and linked activator sequences can independently generate brk-like expression patterns, suggesting that they function as autonomous modules. The fact that the L1 transgene, which contains a single SMM site (#1) also drives a brk-like pattern, strongly argues for a sixth module in addition to the five we have demonstrated (see Figs. 1, 4). Thus the eleven SMM sites in the brk regulatory region likely correspond to a total of 9 or 10 distinct modules, depending on whether the 7/8/9 cluster represents one or more modules. The evolutionary conservation of this unusual promoter organization provides additional support for its functional importance. Analysis of brk flanking regions in D. pseudoobscura and D. virilis which are 30 and 40 million years distant from D. melanogaster, identified 12 and 11 SMM sites respectively, arranged with a similar spacing relative to the basal promoter. Furthermore, eleven sites are found upstream of the brk coding region in the mosquito Anopheles gambiae, separated from Drosophila by ~ 200 million years (L.Y and R.W., unpublished data).

Functional consequences of a modular promoter organization

How does the brk promoter read the pMad gradient and generate a complementary graded expression pattern, and what benefit could the presence of multiple modular enhancers confer in generating the Brk gradient? Our work as well as earlier studies (Muller et al., 2003; Pyrowolakis et al., 2004), indicate that SMM sites act as sensors for Dpp signaling by binding a repressor complex that antagonizes broadly expressed activators in a dose-dependent manner. Our data that SMM-mediated repression has a limited range suggests that each module can autonomously generate an output representing the balance between activation and signaling-dependent repression within that module. The patterns produced by individual modules likely reflect variation in SMM site sequence and affinity, the distance between SMM and activator sites, activator site sequence and number, as well as whether sites for additional transcription factors are present.

The endogenous brk pattern does not appear to reflect the activity of a single ‘dominant’ module, but rather is a composite pattern resulting from integration of multiple modular inputs. This can be inferred from the fact that large promoter fragments containing more than one module (for e.g., L2 and L6) drive patterns that resemble but are not identical to those of their constituent modules. Furthermore, the additive effect of module multimerization on expression levels in regions of low Dpp activity is also consistent with integration across modules (see Fig. 6). Finally, strong support for this idea comes from the buffering capacity of multimodular promoter fragments (see below).

A significant feature of the brk promoter is the remarkable ability of intact modules to override medial activation by mutant modules that are Dpp-insensitive. This is apparent from our data that activators uncoupled from Dpp-dependent repression drive strikingly different expression patterns in isolation, than they do in the context of larger fragments containing additional wild type modules (see Fig. 7). Thus disruption of the SMM sites in module-3 (L12M3), module-4 (L14M4) and module-7/8/9 (L15M7/8/9) caused derepression throughout the center of the wing disc. However the same mutations in a larger fragment containing several additional modules (L13M3, L13M4 and L13M7/8/9) resulted in no derepression in the center of the disc. These results are inconsistent with a simple model in which only modules unbound by SMM complexes contribute to the transcriptional output of the promoter. If this were the case, in cells at the A/P boundary high levels of Dpp signaling would repress all intact modules in the L13M variants, leaving the constitutively active mutant module(s) free to interact with the transcriptional machinery. As a consequence L13M variants would be expected to up-regulate expression throughout the medial region of the disc. One potential explanation for the ability of wildtype modules to dampen expression from mutant modules could be that, activators from SMM-repressed modules may compete disproportionately with activators from unrepressed modules for access to the transcriptional machinery, thus diluting the effect of the mutant modules. Alternatively, the SMM repressor complexes bound at multiple modules could act cooperatively (perhaps by modifying chromatin structure), thus reducing the output from adjacent mutant modules. In both cases, the absence of any expression in the medial region even with two Dpp-insensitive modules present (see Fig. 7H), argues that repressed modules make a significant contribution to the transcriptional output compared to the derepressed modules. Such an integrative mechanism, also provides a framework for understanding how poorly resolved patterns like those generated by module-4 (see Fig. 4D), could be refined to generate the wildtype brk pattern. An important consequence of this promoter logic is that although individual SMM repression complexes act locally, nevertheless modules in aggregate can exert a long range/global effect on promoter activity.

The specialized architecture of the brk promoter may provide a mechanism to respond to Dpp signaling in a uniquely precise and robust fashion. Multiple modules allow simultaneous parallel reads of the pMad gradient, thus increasing the precision with which the brk promoter detects Dpp morphogen levels. Integration would also be predicted to increase the fidelity of the brk promoter response by making it less sensitive to fluctuations at any individual module. This fidelity would be further enhanced by a disproportionate contribution from repressed as opposed to active modules. This buffering ability of the brk promoter is likely to be important in preventing stochastic fluctuations or transcriptional noise in wild type animals (Arias and Hayward, 2006; Blake et al., 2003; Kaern et al., 2005), as well as in rendering brk transcription more resistant to mutational insults.

The brk promoter organization is distinct from other modular promoters

Several developmentally important genes have modular promoters consisting of multiple non-overlapping enhancers that function autonomously to generate a composite expression pattern. The segmentation gene eve provides an archetypal example, with five enhancers that drive expression in seven discrete stripes in the embryonic blastoderm (Fujioka et al., 1999; Goto et al., 1989; Harding et al., 1989). While brk resembles eve in its modular promoter organization and the ability of individual modules to function independently, three key differences make brk unique. First, individual eve elements are bound by different combinations of activators and repressors and thus drive expression in distinct stripes in the embryo. In contrast individual brk modules respond to a common set of repressive cues and drive expression in largely overlapping domains. Second, in any given region of the embryo, the eve pattern represents the output of a single enhancer. In contrast, multiple brk modules are active in each cell and contribute collectively to the final expression pattern. A final crucial difference is that in eve short-range repression prevents cross-talk between enhancers driving expression in different stripes, while in brk the outputs of modules that appear to respond autonomously to the Dpp gradient are integrated. Why do brk and eve cis-regulatory elements display different properties even though both use the CtBP co-repressor? One potential explanation arises from the fact that CtBP functions as part of a complex that includes histone deacetylases, histone methylase/demethylases, and SUMO E2/E3 ligases (Chinnadurai, 2007). CtBP complexed with SMM on the brk promoter may recruit a different subset of activities from a CtBP-gap gene complex on eve enhancers. Also the SMM complex itself may recruit unique activities to the brk promoter. Furthermore, since the activators that mediate brk and eve expression are likely to be distinct, they may be affected by CtBP differentially.

Shn is likely to interact with additional co-repressors and co-activators

Two lines of evidence argue that SMM activity is distance-dependant - Shn interacts directly with the co-repressor dCtBP, and there is a functional requirement for close linkage of SMM sites and activator sequences. Short-range repression appears to be a property of the SMM complex in other contexts as well, since an SMM site located ~89 bp from a germ cell specific enhancer in the bag of marbles (bam) gene fails to mediate repression when this spacing is increased (Chen and McKearin, 2003). Furthermore, an SMM site and activator sequences are closely linked in a compact 514 bp Dpp-dependant enhancer in the gooseberry (gsb) promoter (Pyrowolakis et al., 2004). Loss of dCtBP binding strongly reduces repression by ShnCTM, demonstrating that this interaction is relevant in vivo. However, ShnCTM still retains residual ability to repress brk-LacZ, and brk is not ectopically expressed in dCtBP clones in the wing disc (Hasson et al., 2001; D. Bornemann and R.W, unpublished). This could indicate that the dCtBP interaction motif actually has a different function in vivo. Alternatively Shn may employ redundant repression strategies, consistent with the current view that Shn proteins act as scaffolds for co-repressors, and indeed co-activators and other modulators, enabling the Smad complex to elicit different transcriptional responses dependant on cellular context (Jin et al., 2006; Yao et al., 2006).

The identity of the activator(s) targeted by the SMM repression complex remain to be determined, as do the precise sequences to which it binds. It is possible that different brk modules incorporate inputs from distinct activators, and that some of these activators are spatially or temporally restricted. In addition to inputs from the SMM complex and the activator, there is genetic evidence that brk negatively autoregulates its own expression, most prominently in the medio-lateral regions of the wing disc (Hasson et al., 2001; Moser and Campbell, 2005). Consistent with this the brk promoter contains multiple sites that match the Brk consensus (L.Y and R.W, unpublished data) and may mediate autoregulation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge David Arnosti, Al Courey, Alan Laughon, and Yutaka Nibu for providing reagents. We thank Douglas Bornemann for discussions, unflagging interest and help in developing models. We also thank Arthur Lander for insights, Ira Blitz for comments on the manuscript and an anonymous reviewer for helpful comments. Support was provided by NIH-GM-55442 and MOD-FY2-06-135 to KA, NIH-GM-63024 to CR, and CRCC 34384 and NIH-2R01-GM067247 to RW.

References

- Aihara H, Perrone Lorena, Nibu Yutaka. Transcriptional Repression by the CtBP Corepressor in Drosophila. In: Chinnadurai G, editor. CtBP Family Proteins. Austin, TX: Landes Bioscience; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Arias AM, Hayward P. Filtering transcriptional noise during development: concepts and mechanisms. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:34–44. doi: 10.1038/nrg1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnosti DN. Design and function of transcriptional switches in Drosophila. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;32:1257–73. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(02)00089-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnosti DN, Gray S, Barolo S, Zhou J, Levine M. The gap protein knirps mediates both quenching and direct repression in the Drosophila embryo. Embo J. 1996;15:3659–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora K, Dai H, Kazuko SG, Jamal J, O’Connor MB, Letsou A, Warrior R. The Drosophila schnurri gene acts in the Dpp/TGFß signaling pathway and encodes a transcription factor homologous to the human MBP family. Cell. 1995;81:781–790. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90539-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barolo S, Levine M. hairy mediates dominant repression in the Drosophila embryo. Embo J. 1997;16:2883–91. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake WJ, M KA, Cantor CR, Collins JJ. Noise in eukaryotic gene expression. Nature. 2003;422:633–7. doi: 10.1038/nature01546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell G, Tomlinson A. Transducing the Dpp morphogen gradient in the wing of Drosophila: regulation of Dpp targets by brinker. Cell. 1999;96:553–62. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80659-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, McKearin DM. A discrete transcriptional silencer in the bam gene determines asymmetric division of the Drosophila germline stem cell. Development. 2003;130:1159–70. doi: 10.1242/dev.00325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnadurai G. CtBP, an unconventional transcriptional corepressor in development and oncogenesis. Mol Cell. 2002;9:213–24. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00443-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnadurai G. Transcriptional regulation by C-terminal binding proteins. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:1593–607. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courey AJ, Jia S. Transcriptional repression: the long and the short of it. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2786–96. doi: 10.1101/gad.939601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka M, Emi-Sarker Y, Yusibova GL, Goto T, Jaynes JB. Analysis of an even-skipped rescue transgene reveals both composite and discrete neuronal and early blastoderm enhancers, and multi-stripe positioning by gap gene repressor gradients. Development. 1999;126:2527–38. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.11.2527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S, Laughon A. Decapentaplegic-responsive silencers contain overlapping mad-binding sites. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:25781–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603371200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S, Steffen J, Laughon A. DPP-responsive silencers are bound by a trimeric mad-medea complex. J Biol Chem. 2005 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506882200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto T, Macdonald P, Maniatis T. Early and late periodic patterns of even skipped expression are controlled by distinct regulatory elements that respond to different spatial cues. Cell. 1989;57:413–422. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90916-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding K, Hoey T, Warrior R, Levine M. Autoregulatory and gap gene response elements of the even- skipped promoter of Drosophila. Embo J. 1989;8:1205–1212. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson P, Muller B, Basler K, Paroush Z. Brinker requires two corepressors for maximal and versatile repression in Dpp signalling. Embo J. 2001;20:5725–36. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.20.5725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt GF, Strunk BS, Margulies C, Priputin T, Wang XD, Amey R, Pabst BA, Kosman D, Reinitz J, Arnosti DN. Transcriptional repression by the Drosophila giant protein: cis element positioning provides an alternative means of interpreting an effector gradient. Development. 1999;126:1201–10. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.6.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazwinska A, Rushlow C, Roth S. The role of brinker in mediating the graded response to Dpp in early Drosophila embryos. Development. 1999;126:3323–34. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.15.3323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin W, Takagi T, Kanesashi SN, Kurahashi T, Nomura T, Harada J, Ishii S. Schnurri-2 Controls BMP-Dependent Adipogenesis via Interaction with Smad Proteins. Dev Cell. 2006;10:461–71. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaern M, Elston TC, Blake WJ, Collins JJ. Stochasticity in gene expression: from theories to phenotypes. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:451–64. doi: 10.1038/nrg1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller SA, Mao Y, Struffi P, Margulies C, Yurk CE, Anderson AR, Amey RL, Moore S, Ebels JM, Foley K, et al. dCtBP-dependent and -independent repression activities of the Drosophila Knirps protein. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7247–58. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.19.7247-7258.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick H, Johnson K, Laughon A. Repression of dpp targets by binding of brinker to mad sites. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:18216–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101365200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markstein M, Markstein P, Markstein V, Levine MS. Genome-wide analysis of clustered Dorsal binding sites identifies putative target genes in the Drosophila embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:763–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012591199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marty T, Muller B, Basler K, Affolter M. Schnurri mediates Dpp-dependent repression of brinker transcription. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:745–749. doi: 10.1038/35036383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami M, Kinoshita N, Kamoshida Y, Tanimoto H, Tabata T. brinker is a target of Dpp in Drosophila that negatively regulates Dpp-dependent genes. Nature. 1999;398:242–6. doi: 10.1038/18451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser M, Campbell G. Generating and interpreting the Brinker gradient in the Drosophila wing. Dev Biol. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller B, Hartmann B, Pyrowolakis G, Affolter M, Basler K. Conversion of an extracellular Dpp/BMP morphogen gradient into an inverse transcriptional gradient. Cell. 2003;113:221–33. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00241-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker L, Stathakis DG, Arora K. Regulation of BMP and activin signaling in Drosophila. Prog Mol Subcell Biol. 2004;34:73–101. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-18670-7_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyrowolakis G, Hartmann B, Muller B, Basler K, Affolter M. A simple molecular complex mediates widespread BMP-induced repression during Drosophila development. Dev Cell. 2004;7:229–40. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raftery LA, Sutherland DJ. TGF-beta family signal transduction in Drosophila development: from Mad to Smads. Dev Biol. 1999;210:251–68. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushlow C, Colosimo PF, Lin MC, Xu M, Kirov N. Transcriptional regulation of the Drosophila gene zen by competing Smad and Brinker inputs. Genes Dev. 2001;15:340–51. doi: 10.1101/gad.861401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saller E, Bienz M. Direct competition between Brinker and Drosophila Mad in Dpp target gene transcription. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:298–305. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal D, Gelbart WM. Shortvein, a new component of the decapentaplegic gene complex in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1985;109:119–143. doi: 10.1093/genetics/109.1.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Johnston RD, Hoffmann FM, Blackman RK, Segal D, Grimaila R, Padgett RW, Irick HA, Gelbart WM. Molecular organization of the decapentaplegic gene in Drosophila melanogaster. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1114–27. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.7.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stultz BG, Lee H, Ramon K, Hursh DA. Decapentaplegic head capsule mutations disrupt novel peripodial expression controlling the morphogenesis of the Drosophila ventral head. Dev Biol. 2006;296:329–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanimoto H, Itoh S, ten Dijke P, Tabata T. Hedgehog creates a gradient of DPP activity in Drosophila wing imaginal discs. Mol Cell. 2000;5:59–71. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80403-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thummel CS, Boulet AM, Lipshitz HD. Vectors for Drosophila P-element-mediated transformation and tissue culture transfection. Gene. 1988;74:445–456. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90177-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Vazquez J, Park S, Warrior R, Arora K. The transcription factor Schnurri plays a dual role in mediating Dpp signaling during embryogenesis. Development. 2001;128:1657–70. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.9.1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Vazquez J, Warrior R, Arora K. schnurri is required for dpp-dependent patterning of the Drosophila wing. Dev Biol. 2000;227:388–402. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wharton KA, Jr, Crews ST. CNS midline enhancers of the Drosophila slit and Toll genes. Mech Dev. 1993;40:141–54. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(93)90072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao LC, Blitz IL, Peiffer DA, Phin S, Wang Y, Ogata S, Cho KW, Arora K, Warrior R. Schnurri transcription factors from Drosophila and vertebrates can mediate Bmp signaling through a phylogenetically conserved mechanism. Development. 2006;133:4025–34. doi: 10.1242/dev.02561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.