Abstract

The resolution of acute inflammation is a process that allows for inflamed tissues to return to homeostasis. Resolution was held to be a passive process, a concept now overturned with new evidence demonstrating that resolution is actively orchestrated by distinct cellular events and endogenous chemical mediators. Among these, lipid mediators, such as the lipoxins, resolvins, protectins and newly identified maresins, have emerged as a novel genus of potent and stereoselective players that counter-regulate excessive acute inflammation and stimulate molecular and cellular events that define resolution. Given that uncontrolled, chronic inflammation is associated with many cardiovascular pathologies, an appreciation of the endogenous pathways and mediators that control timely resolution can open new terrain for therapeutic approaches targeted at stimulating resolution of local inflammation, as well as correcting the impact of chronic inflammation in cardiovascular disorders. Here, we overview and update the biosynthesis and actions of pro-resolving lipid mediators, highlighting their diverse protective roles relevant to vascular systems and their relation to aspirin and statin therapies.

Keywords: Resolution, lipid mediators, eicosanoids, omega-3 fatty acids, pro-resolving mediators

Ungoverned inflammation is a prominent characteristic of many chronic diseases, such as arthritis and diabetes, as well as cardiovascular diseases, including atherosclerosis, myocarditis, heart failure and vasculitis1–4. Anti-inflammatory therapies aimed at blocking pro-inflammatory pathways are widely used. Among these, synthetic corticosteroids, cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors and anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) antibodies are prominent examples5–10. While this approach has proven efficacious in certain clinical settings, inhibiting pro-inflammatory pathways can in some cases be detrimental (e.g. selective COX-2 inhibitors), thus effective therapeutics aimed at controlling chronic inflammation remain of interest6, 9–11. We focused on mapping endogenous cellular and biochemical pathways that operate during self-limited acute inflammatory responses that enable the return to homeostasis12, 13. This systematic approach with in vivo inflammatory exudates uncovered novel chemical mediators that are actively biosynthesized during resolution of inflammation, and potently stimulate this vital process. The identification of these new mechanisms and pathways challenged the pre-existing paradigm that inflammation passively terminates13. Within this context, a detailed appreciation of the endogenous pathways that actively turn off acute inflammation and stimulate resolution opens many new avenues for therapeutics and prevention that are aimed at controlling excessive inflammation without apparent immunosuppression.

Inflammation and its natural resolution

The acute inflammatory response is a protective, physiologic program that protects the host against invading pathogens. Local chemical mediators biosynthesized during acute inflammation give rise to the macroscopic events characterized by Celsus in the 1st century, namely, rubor (redness), tumor (swelling), calor (heat) and dolor (pain)12. Although these cardinal signs of inflammation were evident over 2000 years ago, the cellular and molecular events that regulate the inflammatory response and its timely resolution are only recently beginning to be appreciated. Tissue edema is one of the earliest events of the acute inflammatory response that arises from increased permeability of microvasculature. Polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN) are the first line of defense against microbial invasion, which contain potentially harmful stimuli via phagocytosis. PMN traverse post-capillary venules at sites of inflammation, degrade pathogens within phagolysosomes, and undergo apoptosis. Next, mononuclear cells infiltrate, differentiate into macrophages, and clear apoptotic PMN by phagocytosis in a non-inflammatory manner termed efferocytosis 14. Ultimately, clearance of microbes and efflux of phagocytes allows for the tissue to return to homeostasis13. Disruption of any of these specific checkpoints could potentially give rise to chronic inflammation, which is characterized primarily by excessive leukocyte infiltration and activation, delayed clearance, resultant tissue damage, and loss of function15. Indeed, cardiovascular diseases such as atherosclerosis display many of these features16–18.

Lipid mediators (LM) biosynthesized from essential fatty acids play pivotal roles in distinct phases of the inflammatory response13, with prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and cysteinyl leukotrienes (cysLTs) promoting early vascular permeability and leukotriene B4 (LTB4) stimulating leukocyte chemotaxis19. Prostaglandins play additional roles during the acute inflammatory response, including the regulation of local changes in blood flow and pain sensitization (reviewed in 20). During evolution of an inflammatory exudate, the profile of LM autacoids changes to biosynthesis of counter-regulatory mediators that limit further PMN congregation and stimulate resolution21–23. While the mechanisms that mediate progression from acute to chronic inflammation are not completely understood, chronic inflammation is widely viewed as an excess of pro-inflammatory mediators11. In view of mounting evidence from the authors’ laboratory, and now many other groups, it is also plausible that disruptions in endogenous pro-resolving circuits could underlie some of the aberrant mechanisms that lead to chronic inflammation1, 11, 13, 15.

Complete resolution of an acute inflammatory response is the ideal outcome following an insult12. In order for resolution to ensue, further leukocyte recruitment must be halted and accompanied by removal of leukocytes from inflammatory sites. These key events governing resolution of inflammation are the focus of our work and collaborators. In particular, we sought to identify mechanisms that regulate these key histological events in resolution using an unbiased systems approach to profile self-limited inflammation employing liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)21, 22, 24–26. These analyses identified novel LM and also provided information regarding their biosynthetic pathways and further metabolic inactivation products. It is noteworthy that, in addition to novel LM overviewed here, other important components of resolution are emerging (i.e. NF-κB, annexin-1, specific prostanoids). They are beyond the scope of this concise update and interested readers are directed to 8, 11, 23, 27.

Pro-resolving lipid mediators: Autacoid signals in exudates

Using experimental models of self-resolving acute inflammation, we uncovered a new genus of autacoids that possess potent anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving actions. These include lipoxins, which are generated from arachidonic acid (AA), resolvins, protectins, and newly identified maresins, which are generated from omega-3 fatty acids. The enzymatic generation of these families occurs primarily via transcellular biosynthesis, and in some cases within a single cell type, via lipoxygenase (LOX) enzymes. They are potent, stereoselective agonists controlling both the magnitude and duration of an acute inflammatory response. The biosynthesis and actions of each of these families of endogenous counter-regulatory autacoids are overviewed herein.

Lipoxins

Lipoxins are generated in humans from AA via LOX enzymes and comprise two distinct regioisomers, lipoxin A4 (LXA4) and LXB4. Lipoxins were the first mediators recognized to have both anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving actions28. Their biosynthesis proceeds via 15-LOX - mediated conversion of AA to 15-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (HETE), which is further transformed via 5-LOX and subsequent reactions to LXA4 and LXB4 during cell:cell interactions (e.g. epithelial:leukocyte, leukocyte:leukocyte). Lipoxins are also generated in the vasculature during platelet:leukocyte interactions, in which the intermediate in leukotriene biosynthesis, leukotriene A4 (LTA4), is produced within leukocytes and converted to lipoxins by platelet 12-LOX29. In addition to LOX-initiated lipoxin biosynthesis, an intriguing novel route involving COX-2 was uncovered. In the presence of aspirin, acetylated COX-2 loses activity required to form prostaglandin H2 (PGH2), but retains oxygenase activity to produce 15R-HETE from arachidonate. This intermediate, like 15S-HETE, is transformed via 5-LOX to generate epimeric lipoxins, termed aspirin-triggered (AT) or 15-epi-lipoxins30. The 15-epi-lipoxins share the potent bioactions of lipoxins, suggesting that their formation could underlie the anti-inflammatory actions of aspirin that cannot be attributed only to the inhibition of prostanoid formation (vide infra). Of note, 15-epi-lipoxin biosynthesis can also be initiated by cytochrome P450 enzymes and this important pathway may underlie the generation of 15-epi-lipoxins in the absence of aspirin31. In humans, low dose aspirin limits PMN infiltration via local 15-epi-lipoxin formation that in turn stimulates nitric oxide (NO) production (vida infra)32, 33.

The temporal generation and biological role of endogenous lipoxins was elucidated using animal models of sterile inflammation. The initial formation of leukotrienes corresponds with an increase in PMN infiltration and is followed by a progressive increase in prostaglandin formation, namely PGE2 and PGD221. Next, the profile of lipid mediators switches from pro-inflammatory eicosanoids to lipoxins, whereby PGE2 and PGD2 stimulate upregulation of 15-LOX, a process termed “lipid mediator class switching”21. Thus, although COX-2 derived pro-inflammatory eicosanoids are commonly viewed as harmful, they are critical for positive feed-forward regulation of anti-inflammatory LM circuits. Importantly, recent studies have shown that inhibition of COX-2 delays resolution of inflammation25, 27. Thus, in addition to inhibiting the formation of protective prostaglandins (e.g. prostacyclin)10, selective COX-2 inhibitors also interfere with endogenous resolution programs. The role of lipoxins in counter-regulating leukocyte trafficking was demonstrated in both animal and human systems, where administration of LXA4 reduces PMN transmigration, adhesion receptor expression, pro-inflammatory cytokine generation and excessive PMN infiltration into inflamed tissues (Tables 1 and 2)13, 24, 34.

Table 1.

Cellular actions of lipoxins, resolvins and maresins.

| Lipid Mediator | Target Cell | Action(s) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipoxin A4 (or aspirin-triggered Lipoxin A4) | |||

| Endothelial cells | Blocks ROS generation; Inhibits VEGF-induced migration/proliferation; Decreases ICAM-1 expression; Stimulates PGI2 & NO formation; Stimulates HO-1 expression |

33, 93–95, 113 | |

| Vascular smooth muscle cells | Decreases PDGF-stimulated migration | 96 | |

| Macrophages | Stimulates non-phlogistic phagocytosis | 25, 35 | |

| T-cells | Upregulates CCR5 expression; Inhibits TNF secretion |

69, 123 | |

| Fibroblasts | Blocks MMP-3 production | 124 | |

| Neutrophils | Blocks superoxide generation; Reduces CD11b/CD18 expression; Blocks neutrophil:endothelial interactions; Inhibits peroxynitrite formation |

125–127 | |

| Resolvin E1 | |||

| Macrophages | Stimulates non-phlogistic phagocytosis; Binds to ChemR23 in a stereospecific manner |

25, 47 | |

| Vascular smooth muscle cells | Decreases PDGF-stimulated migration | 96 | |

| Platelets | Reduces aggregation/activation | 54 | |

| Neutrophils | Blocks transmigration; Acts as partial agonist/antagonist of BLT-1 & blocks LTB4-stimulated Ca2+ mobilization |

22 | |

| Dendritic cells | Reduces IL-12 production | 47 | |

| Resolvin D1 | |||

| Neutrophils | Binds ALX and GPR32 & decreases LTB4-stimulated actin polymerization; Blocks transmigration |

61, 63 | |

| Macrophages | Enhances phagocytosis in a receptor-dependent manner | 63 | |

| Resolvin D2 | |||

| Endothelial cells | Stimulates NO & PGI2 production; Blocks leukocyte:endothelial interactions |

62 | |

| Neutrophils | Enhances microbial phagocytosis; Decreases extracellular ROS generation; Reduces CD18 expression & L-selectin shedding |

62 | |

| Macrophages | Enhances phagocytosis | 62 | |

| Maresin 1 | |||

| Macrophages | Enhances phagocytosis | 76 |

Table 2.

Lipoxins and aspirin-triggered lipoxins in animal models of disease.

| Disease model | Species | Action(s) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma | Mouse | Attenuates pulmonary inflammation & airway hyper-responsiveness | 128 |

| Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury | Mouse | Decreases hind-limb ischemia/reperfusion injury in the lung; attenuates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury | 34, 129 |

| Dermal Inflammation | Mouse | Decreases vascular permeability | 130 |

| Periodontitis | Rabbit | Decreases bone loss; reduces PMN accumulation | 131 |

| Peritonitis | Mouse | Decreases PMN infiltration; enhances phagocytosis & clearance of apoptotic cells | 24, 25 |

| Cystic Fibrosis | Mouse | Decreases disease severity, inflammation & bacterial burden | 81 |

| Angiogenesis | Mouse | Counter-regulates VEGF-induced pathologic neo-vascularization | 113 |

Pro-resolving signals

Along with the anti-inflammatory role of lipoxins in negatively regulating leukocyte infiltration into tissues, lipoxins also stimulate resolution. Within inflammatory exudates, PMN undergo apoptosis and must be cleared to prevent unwarranted tissue damage. In this regard, lipoxins and 15-epi-lipoxins stimulate phagocytosis of apoptotic PMN by macrophages in a non-phlogistic (non-fever causing) manner25, 35. Lipoxins also stimulate the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10, in macrophages and promote macrophage efflux to peripheral lymph nodes. Thus, lipoxins are dual acting mediators that not only reduce further leukocyte infiltration, but also promote their removal from inflamed sites1, 25.

LXA4 elicits its actions in nanomolar concentrations via agonist signaling by a specific G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) termed ALX (also denoted formyl peptide receptor 2; FPR2)29. Specific binding of LXA4 to ALX is stereoselective and ALX signaling mediates the protective actions of LXA4 in myeloid cells, which include inhibition of NF-κB activation, blockade of leukotriene biosynthesis, attenuation of superoxide production and regulation of leukocyte chemotaxis (Figure 1 and Table 1). Regulation of leukocyte trafficking by lipoxin A4 is partly dependent on direct stimulation of the suppressor of cytokine synthesis (SOCS-2) pathway36. Of note, LXA4 counter-regulates vascular smooth muscle cell migration37 induced by cysLTs and serves as a cysLT1 receptor antagonist38. The role of specific GPCRs in mediating diverse protective actions of lipoxins is evidenced by targeted overexpression and genetic deletion of both human and murine homologs of ALX/FPR239 in murine systems40, 41.

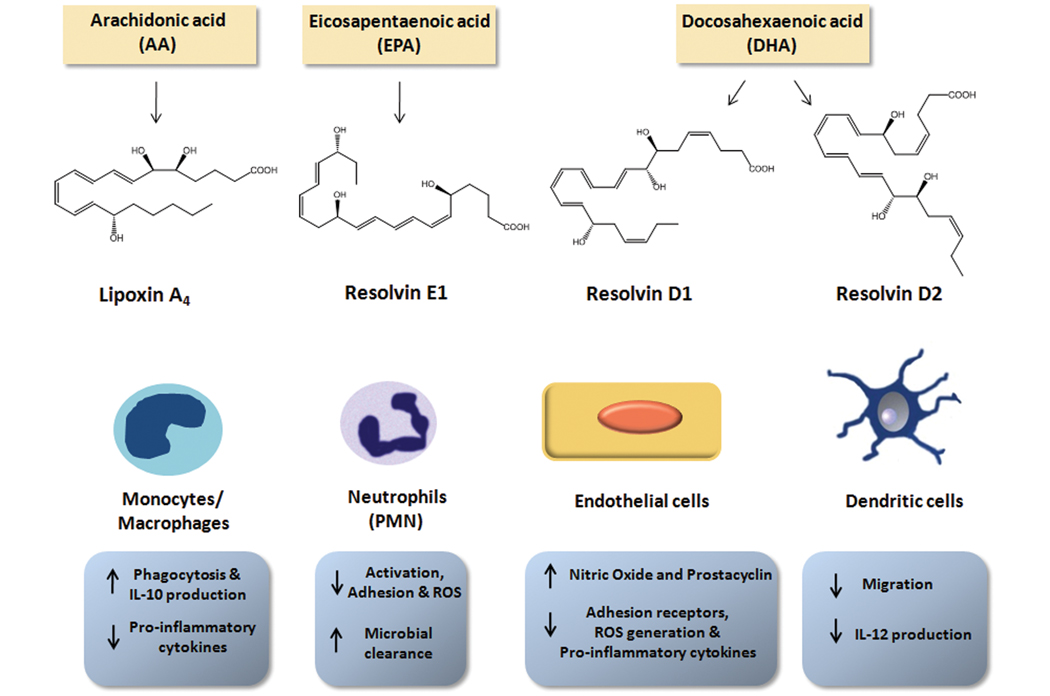

Figure 1. Key cellular actions of lipoxins and resolvins.

Lipoxin A4 is generated from arachidonic acid (AA), while omega-3 fatty acids, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), serve as precursors for E-series and D-series resolvins, respectively. Lipoxins and resolvins act in a stereospecific manner on distinct cell types through interaction with G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) to stimulate non-phlogistic macrophage phagocytosis, increase anti-inflammatory cytokines and decrease pro-inflammatory cytokine generation in macrophages, neutrophils (PMN), endothelial cells and dendritic cells. Lipoxins and resolvins also stimulate endothelial production of nitric oxide (NO) and vasoprotective prostacyclin (PGI2).

The Omega-3 pro-resolution mediators: Resolvins, Protectins and Maresins

The importance of essential omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in humans is evidenced by multiple studies demonstrating that dietary omega-3s have beneficial cardiovascular effects42. Of note, a diet rich in omega-3s is recommended by the American Heart Association (www.americanheart.org). It was first observed that Greenland Eskimos, who have a diet high in cold water fish, have a low rate of ischemic heart disease43. These findings were validated in numerous human and animal studies using purified fish oil extracts rich in omega-3s, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Most notably, the Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto miocardico (GISSI) Prevenzione trial demonstrated that omega-3 dietary supplementation (1 g/day) reduced the risk of cardiovascular death in a patient population of > 2,000 that had suffered a prior myocardial infarction44. More recently, GISSI Prevenzione determined that omega-3 supplementation also reduces the risk of death from congestive heart failure in a placebo-controlled, double blind, randomized study of over 6,000 heart failure patients45. Although multiple beneficial actions of omega-3 supplementation are widely appreciated, the mechanisms underlying their protection in complex disease remained to be identified. At higher concentrations, omega-3s act on ion channels, are metabolized to inactive eicosanoids of the 3-series prostaglandins and 5-series leukotrienes, and change cell membrane physical properties. However, the role of omega-3s in resolution of inflammation was unknown.

To address the molecular basis for anti-inflammatory properties of omega-3s, an unbiased LC-MS/MS-based informatics approach was devised to identify novel mediators generated from omega-3 precursors during acute inflammation in vivo. Using this approach, EPA and DHA were found to be enzymatically converted into novel potent LM coined resolvins for resolution phase interaction products22, 24, 26. Resolvins represent a new distinct family of mediators generated from omega-3s during resolution. Importantly, biosynthesis of resolvins gives rise to stereospecific local mediators that have potent actions and activate specific receptors. Therefore, resolvins are distinct from auto-oxidation products that can arise from EPA and DHA on food spoiling or in vivo during oxidative stress46.

E-series Resolvins

The first evidence that EPA serves as a precursor for bioactive mediators during resolution of inflammation was obtained in sterile, self-limited inflammation in mice. As >90% of patients enrolled in the GISSI Prevenzione trial were taking aspirin in addition to omega-3s44, and our earlier finding that aspirin-acetylated COX-2 gives rise to 15-epi-lipoxins, it was of interest to determine whether this combination would promote the formation of unique chemical mediators generated from EPA during resolution. In mice administered EPA and aspirin, PMN infiltration into inflamed tissues decreased and correlated with conversion of EPA to 18R-hydroxyeicosapentaenoic acid (18R-HEPE), as well as other related bioactive compounds. LM-lipidomics revealed that EPA is converted in vivo to a novel bioactive trihydroxy-conjugated triene and diene-containing mediator22. This biosynthetic pathway was recapitulated with hypoxic human endothelial cells exposed to EPA and aspirin, in which 18R-HEPE was generated and converted to the mediator by activated human PMN via 5-LOX22. The complete structure of this mediator, coined resolvin E1 (RvE1), was elucidated via total organic synthesis based on the proposed biosynthesis and basic structure (see abbreviations)22, 47. Add back of RvE1 during acute inflammation markedly reduced PMN infiltration and decreased pro-inflammatory cytokines, results that provided the first evidence for the in vivo molecular basis of anti-inflammatory, anti-PMN actions of EPA.

Given these potent actions, we reasoned that RvE1 might activate specific receptors to promote resolution. Screening of candidate GPCRs related in sequence to ALX revealed that RvE1 stereoselectively binds ChemR23, a previous orphan receptor47. In isolated cells transfected with ChemR23, RvE1 inhibits TNF-α stimulated NF-κB activation, consistent with in vivo actions of RvE1 in blocking TNF-α stimulated leukocyte trafficking. Of note, the endogenous role of ChemR23 in counter-regulating inflammation was recently demonstrated in mice with a genetic deletion of ChemR2348. Acting via ChemR23, RvE1 stimulates downstream signaling through the phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway, leading to activation of the translational regulator, ribosomal protein S649. This pathway is involved in RvE1 stimulation of macrophage phagocytosis. ChemR23 is highly expressed on dendritic cells and monocytes, although its expression is low on PMN47, 50. As RvE1 blocks PMN migration in vitro and displays specific binding on human PMN, this suggested that RvE1 might bind additional GPCRs. Indeed, RvE1 signals as a partial agonist/antagonist via the LTB4 receptor, BLT1, and attenuates LTB4-induced pro-inflammatory signaling in PMN50.

The multilevel potent actions of RvE1 were demonstrated on human cells and in acute and chronic inflammatory pathologies. As summarized in Table 3, RvE1 regulates leukocyte trafficking and pro-inflammatory signaling to promote resolution of peritonitis, colitis, periodontitis (a chronic infectious inflammation) and retinopathy25, 51–53. RvE1 also displays potent actions on human platelets. Humans taking both aspirin and EPA increase RvE1 levels in plasma50, and RvE1 blocks ADP and thromboxane-stimulated platelet aggregation without affecting either collagen or thrombin-stimulated activation54.

Table 3.

Anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving actions of resolvins and maresins in animal models of disease.

| Disease model | Species | Action(s) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolvin E1 | |||

| Peritonitis | Mouse | Stops neutrophil recruitment; regulates chemokine/cytokine production Promotes lymphatic removal of phagocytes |

22, 24, 47 |

| Retinopathy | Mouse | Protects against neovascularization | 52 |

| Colitis | Mouse | Decreases neutrophil recruitment & pro-inflammatory gene expression; improves survival; reduces weight loss | 51 |

| Pneumonia | Mouse | Improves survival; decreases neutrophil infiltration; enhances bacterial clearance; reduces pro-inflammatory cytokines | 109 |

| Inflammatory Pain |

Mouse | Reduces inflammatory pain induced by formalin, carrageenan or Freund’s complete adjuvant; Blocks capsaicin and TNF-α induced heat and mechanical hypersensitivity |

132 |

| Resolvin D1 | |||

| Peritonitis | Mouse | Reduces neutrophil recruitment; Blocks oxidative-stress induced peritonitis |

60, 61, 133 |

| Kidney ischemia-reperfusion | Mouse | Decreases fibrosis &protects from ischemia-reperfusion-induced kidney damage & loss of function | 72 |

| Retinopathy | Mouse | Reduces pathologic neovascularization | 52 |

| Inflammatory Pain | Mouse | Reduces inflammatory pain induced by formalin, carrageenan or Freund’s complete adjuvant | 132 |

| Resolvin D2 | |||

| Sepsis (CLP) | Mouse | Reduces systemic cytokine storm ; Enhances bacterial clearance ; Improves survival ; Regulates leukocyte trafficking ; Protects from hypothermia |

62 |

| Peritonitis | Mouse | Decreases neutrophil recruitment | 62 |

| Maresin 1 | |||

| Peritonitis | Mouse | Reduces neutrophil recruitment | 76 |

A second bioactive member of the E-series was identified that shares an intermediate in RvE1 biosynthesis. It was earlier proposed that enzymatic conversion of 18R-HEPE to RvE1 involves the formation of an epoxide. The 5S-hydroperoxide formed prior to epoxidation can undergo reduction to 5S,18(R/S)-dihydroxy-eicosapentaenoic acid, denoted resolvin E2 (RvE2)55. RvE2 shares some of the potent actions of RvE1, namely reducing PMN infiltration in peritonitis, and acts in an additive fashion with RvE1. Interestingly, differences in biological activity were observed that depend on the route of administration (i.e. intravenous vs. intraperitoneal) suggesting that the targets and receptors for RvE1 and RvE2 may be distinct. Further studies are warranted to appreciate the specific biosynthesis of RvE1 and RvE2 and their respective sites of action. Thus, given that E-series resolvins are biosynthesized and have direct actions within the vasculature, the importance of this pathway and related products in cardiovascular disease is an area of ongoing investigation.

D-series Resolvins

DHA also has numerous beneficial actions in the cardiovascular system42, 56–59. Exogenous DHA reduces expression of vascular endothelial adhesion molecules, such as VCAM-1 and ICAM-1, induced by pro-inflammatory stimuli and thus regulates leukocyte:endothelial interactions57. However, the amounts of DHA required to elicit these effects are generally high, i.e. µM range in vitro or gram dose ranges in vivo. Thus, it was important to determine whether DHA might also serve as a precursor to endogenous autacoids. In mice given DHA plus aspirin, a monohydroxy product, namely 17R-hydroxydocosahexaenoic acid, was generated during resolution. Both dihydroxy and trihydroxy structures biosynthesized from DHA were also identified within resolving exudates. These bioactive molecules were coined aspirin-triggered (AT) D-series resolvins because they enhance resolution26. To identify potential cellular sources of these, the proposed biosynthetic pathway was recapitulated in human cells. Hypoxic endothelial cells treated with aspirin converts DHA to 17R-hydroxydocosahexaenoic acid, which is transformed by leukocytes into D-series resolvins. Importantly, DHA is converted into resolvins in human whole blood in the absence of aspirin60. Notably, D-series resolvins generated in the absence of aspirin carry the alcohol at the 17 position in predominantly the S configuration, rather than R configuration60. Addition of this precursor to activated human PMN also generated D-series resolvins, again highlighting the importance of cell-cell interactions (as occurs during resolution of inflammation). The enzymatic pathway leading to the formation of D-series resolvins is shown in Figure 2. Additional bioactive members of this family were identified and characterized (RvD3–RvD6). Each of these arises by similar biosynthetic routes, but have distinct structures and potentially additional bioactions13.

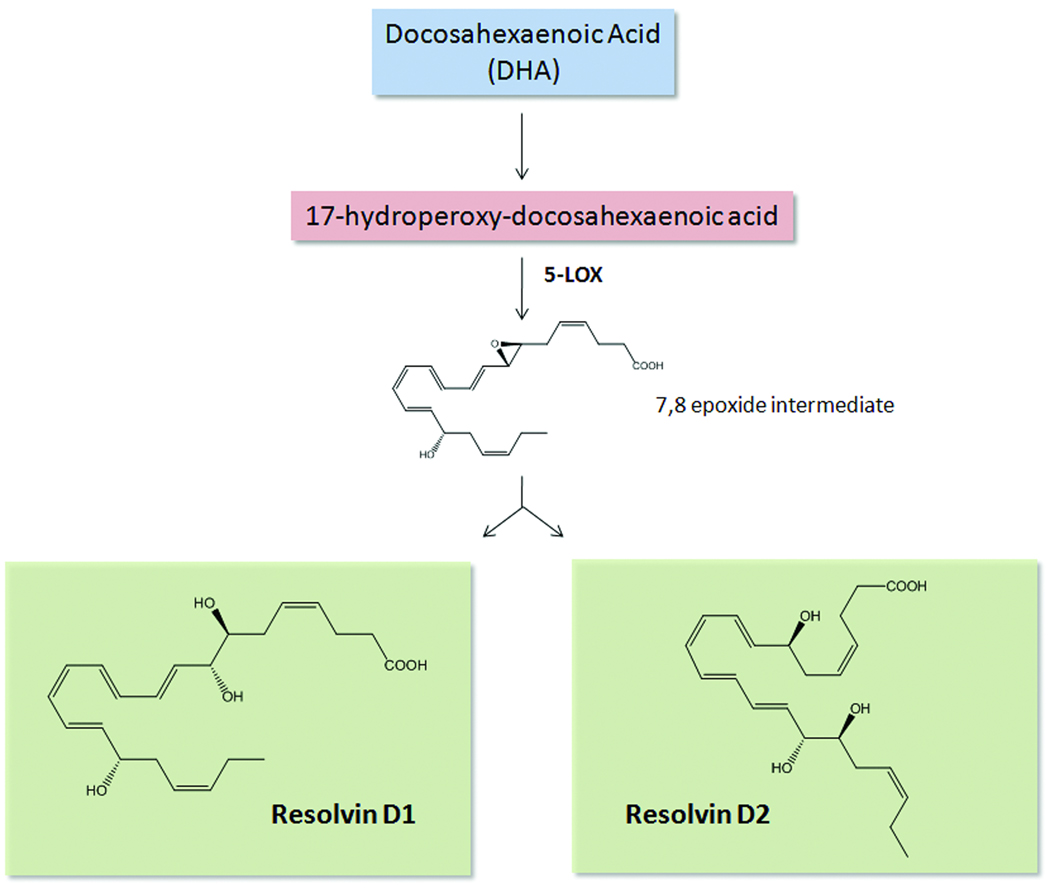

Figure 2. Biosynthetic scheme of D-series resolvins.

Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) is enzymatically converted to 17-hydroperoxydocosahexaenoic acid by 15-lipoxygenase (LOX). The 17-hydroperoxy intermediate is further transformed by 5-LOX via transcellular biosynthesis to form a 7,8-epoxide intermediate, which is enzymatically hydrolyzed to either resolvin D1 (RvD1) or RvD2. In the presence of aspirin, acetylated COX-2 converts DHA into 17-hydroxydocosahexaenoic acid in which the hydroxyl group is in the R configuration, rather than the S configuration. This intermediate is further transformed into aspirin-triggered RvD1 and RvD2.

Following complete structural elucidation, stereochemical assignment and total organic synthesis, the bioactions of both native and AT D-series resolvins were elucidated13, 26, 61. We recently established the complete structure and stereochemical assignment of RvD262. D-series resolvins have multiple beneficial actions both in vivo, and in isolated human cells (Figure 1 and Tables 1 and 3). In particular, they reduce excessive PMN infiltration into inflamed tissues, decrease PMN activation and promote phagocytosis and clearance of apoptotic cells and microbes. Protective actions of D-series resolvins have been observed in both acute and chronic inflammatory diseases, such as peritonitis, ischemia/reperfusion injury, and sepsis (Table 3). The unique mechanism of action for resolvins involves both limiting PMN infiltration and enhanced macrophage phagocytosis that uses specific receptors recently identified on human PMN, monocytes, and macrophages63. RvD1 signals via a GPCR denoted GPR32 that was an orphan human receptor. Interestingly, RvD1 was also found to activate ALX, in addition to serving as an agonist for GPR32. Signaling through these receptors, RvD1 counter-regulates LTB4-stimulated surface expression of β2 integrins, reduces actin polymerization, and enhances macrophage phagocytosis. Of note, classic GPCR second messengers, cAMP and Ca2+ are not activated by RvD1 signaling in PMN.

Protectins: docosatrienes and other novel products

In addition to DHA-derived resolvins, resolving exudates also contained novel 10,17S-dihydroxydocosatrienes, as well as other novel products including 7S,17S-diHDHA and 4S,17S-diHDHA. These dihydroxy-containing products and their regulatory actions in dermal inflammation and peritonitis were first reported in26. Further experiments revealed that DHA was transformed to 10,17S-docosatriene, 16,17S-docosatriene and D-series resolvins in whole blood, leukocytes, brain and glial cells60. In human glial cells, 10,17S-docosatriene potently regulated IL-1β and extracellular acidification, providing evidence that this compound is a ligand, evoking rapid cellular responses, Also, an omega-22 hydroxylation product of 10,17S-docosatriene was identified, suggesting that once 10,17S-docosatriene evokes its action, it is inactivated60. Studies with Bazan et al. demonstrated that 10,17S-docosatriene reduces stroke damage in part by limiting neutrophilic infiltration64. Based on its potent actions in human retinal pigmented epithelial cells and neutrophils, this 10,17-docosatriene was coined neuroprotectin D1 (NPD1) when produced in the vicinity of neural tissues, and protectin D1 (PD1) in the immune system65, 66. The identification of these biologically active endogenous products, isomers and related compounds biosynthesized from DHA provided evidence that a larger family with this basic structure from a 22-carbon backbone was warranted, and the family was coined protectins67.

PD1 is also biosynthesized by T cells and regulates apoptosis68. During peritonitis, PD1 is formed from endogenous DHA and accumulates during resolution24. PD1 has a number of potent bioactions evident in the pico-nanogram range, including the ability to limit PMN infiltration and reduce cytokine/chemokine levels during acute inflammation. Importantly, PD1 shortens the resolution interval24, 25. Hence, it was important to establish the complete stereochemistry of NPD1/PD1, which was assigned by matching with compounds prepared via total organic synthesis. PD1 proved additive with RvE1, and halted leukocytic infiltration following the initiation of an inflammatory response when administered ~two hours following exposure to challenge. Lipoxin A4, RvE1 and PD1 stimulate resolution in part by stimulating the sequestration of chemokines on T cells and apoptotic PMN by their ability to regulate CCR5 expression69. This event results in macrophage engulfment and clearing of chemokines from inflammatory sites. Transgenic mice overexpressing the fat-1 gene, which encodes a desaturase enzyme that enables the endogenous conversion of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids, are protected from a number of inflammatory insults and have higher levels of resolvins and protectins70. Levels of NPD1/PD1 are also increased in the bone marrow of mice consuming a diet rich in omega-3s71, which is renal protective via NPD1/PD1’s ability to regulate leukocyte trafficking72. Along these lines, PD1 was identified in human breath condensates obtained from healthy subjects and is diminished in exhaled breath condensates obtained from asthmatics. In murine airways, PD1 markedly accelerates resolution of airway inflammation and regulates eosinophil, T lymphocyte, mucus and pro-inflammatory mediator levels, including IL-13, leukotrienes and prostaglandins73. The important role of NPD1/PD1 in regulating retinal and neural pathophysiolgy was recently reviewed74. Trapping products indicate the involvement of an epoxide intermediate in the biosynthesis of NPD1 in retinal pigment epithelial cells, and evidence for stereoselective specific binding sites with human PMN and retinal pigmented epithelial cells was obtained75.

Maresins

Macrophages are key players in resolution and their presence in inflamed tissues is vital for tissue repair, wound healing and the restoration of homeostasis11. Recently, a new lipid mediator biosynthetic pathway was identified that involves enzymatic conversion of DHA by macrophages during resolution. Late-stage resolving exudates accumulated 14S-hydroxydocosahexaenoic acid, in addition to 17-hydroxydocosahexaenoic acid, a marker of resolvin biosynthesis. Given that monohydroxy fatty acids are markers of biosynthetic pathways leading to potent downstream mediators, as is the case for leukotrienes, lipoxins and resolvins, it was reasoned that 14-hydroxydocosahexaenoic acid might be a marker of previously unrecognized mediator pathway operative during resolution and homeostasis. Using isolated human and murine macrophages, we found that these cells convert DHA into 14-hydroxydocosahexaenoic acid and a novel 7,14-dihydroxy-containing product that showed potent anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving actions76. Addition of either DHA or 14S-hydroperoxydocosahexaenoic acid to macrophages transformed these substrates into the dihydroxy mediator, the complete structure of which was established76. Given its potent stereoselective actions and in vivo production, we coined this new family the maresins (macrophage mediators in resolving inflammation); specifically the lead mediator as maresin 1 (MaR1)76. These findings lend further support to the concept that local enzymatic conversion of DHA to bioactive and stereoselective mediators could indeed underlie the essential role of DHA.

Aspirin, COX-2 and pro-resolving pathway of local mediators

Aspirin is one of the most widely used anti-inflammatory drugs, and low-dose aspirin (81 mg) is currently recommended by the American Heart Association (www.americanheart.org) for both primary and secondary prevention of myocardial infarction, stroke, and unstable angina. The beneficial actions of aspirin in the cardiovascular system have been widely attributed to the well-documented ability of aspirin to block prostaglandin and pro-thrombotic thromboxane (TXA2) generation via acetylation of COX-177. Notably, aspirin has additional anti-inflammatory actions, such as blocking leukocyte trafficking to inflamed tissues, which cannot be attributed only to aspirin’s ability to inhibit prostanoid biosynthesis27, 78. As noted (vide supra), aspirin acetylation of COX-2 not only inhibits prostanoid formation, but alters the active site of COX-2 and thereby permits conversion of AA to 15R-HETE in vascular endothelial cells. This intermediate can be further transformed to epimeric lipoxins by leukocytes (Figure 3). The formation of 15-epi-lipoxins is documented in healthy individuals taking low-dose aspirin and was shown to be both age and gender dependent79, 80. Recently, the anti-inflammatory actions of aspirin were documented during acute inflammation in humans. Oral administration of low-dose aspirin reduced leukocyte accumulation in cantharidin-induced skin blisters and was associated with both 15-epi-lipoxin biosynthesis and an increase in ALX expression33.

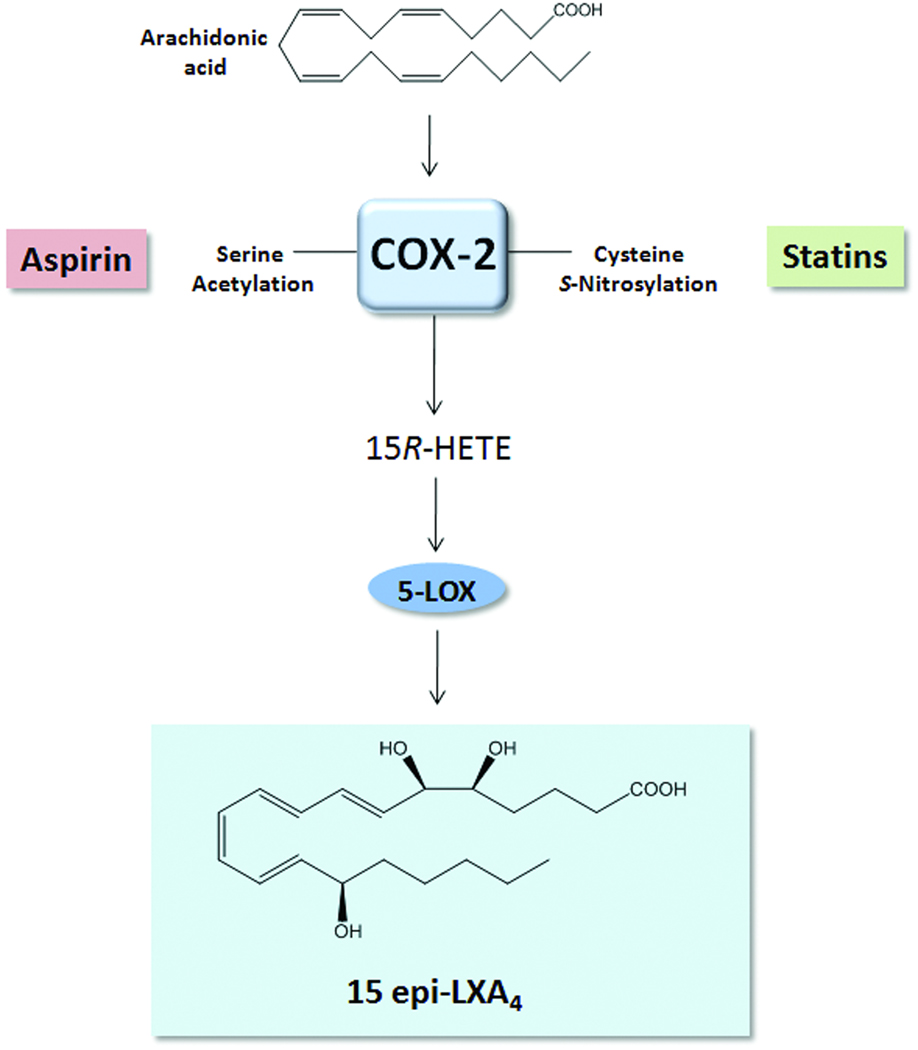

Figure 3. Aspirin and statins promote the formation of 15-epi lipoxin A4.

Both aspirin and statins promote the generation of 15R-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (HETE) from arachidonic acid via the acetylation or S-nitrosylation of COX-2, respectively. Through transcellular biosynthesis, 15R-HETE is further converted to 15-epi lipoxin A4 by 5-lipoxygenase (LOX).

As noted, both EPA and DHA are substrates for acetylated COX-2, which generates biosynthetic precursors to AT-resolvins. The AT-resolvins share potent anti-inflammatory actions of native resolvins61. Thus, it can be considered that aspirin, in addition to blocking pro-inflammatory lipid mediator production, stimulates resolution via the generation of bioactive epimers of lipoxins and resolvins. These actions could underlie the multiple beneficial effects of aspirin in complex cardiovascular diseases and suggest that formation of pro-resolving lipid mediators could, in part, explain the distinct anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution actions of aspirin.

LXA4 and aspirin-triggered 15-epi-lipoxin A4 in animal models and human diseases

The potent anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving actions of lipoxins and epi-lipoxins have been demonstrated in multiple animal models of human diseases (Table 2). Both native LXA4 and 15-epi-lipoxin A4 bind and activate ALX and decrease PMN infiltration in murine and rat models of acute peritonitis29. The endogenous protective role of ALX mediating the biological actions of lipoxins has been demonstrated in mice overexpressing the human lipoxin receptor in myeloid cells and more recently in mice lacking the murine homolog of ALX, FPR240, 41. Numerous studies have further demonstrated that the progression of inflammation in chronic diseases, such as asthma, scleroderma lung disease and cystic fibrosis, is associated with deficiencies in lipoxin production and/or an imbalance between pro-inflammatory eicosanoids and lipoxins81–83. Accordingly, restoration of these deficiencies resolves inflammation associated with these diseases, decreasing leukocyte accumulation and pro-inflammatory cytokine generation. In addition to regulating excessive leukocyte responses, lipoxins also decrease fibrosis in lung injury and in renal mesangial cells84, 85. It is noteworthy that several generations of stable analogs of lipoxins and 15-epi-lipoxins were prepared that are longer lived, and share the potent biological actions of endogenous lipoxins in vitro and in vivo86. Lipoxins are currently in clinical development, and it is clear that their potent actions in regulating leukocyte responses, fibrosis and tissue injury can have far-reaching clinical implications.

Statins and pro-resolving lipid mediators

Statins (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl (HMG)-CoA reductase inhibitors) represent a widely used class of therapeutics that have well-documented actions in reducing low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels in humans. While reducing LDL levels provides a prominent mechanism whereby statins reduce the risk of cardiovascular events (e.g. myocardial infarction, sudden cardiac death), accumulating evidence suggests that statins have additional anti-inflammatory properties that may underlie their diverse protective actions in the cardiovascular system5. Indeed, numerous studies have demonstrated that statins reduce acute inflammation in vivo, in part via direct regulation of leukocyte-endothelial interactions5, 87. Recently, results of the JUPITER trial (Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: An Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin) demonstrated that Rosuvastatin (20 mg/day) reduced systemic markers of inflammation (e.g. C-reactive protein) and provided an additional clinical benefit beyond lowering cholesterol levels in patients, namely reducing major cardiovascular events88. Recent results demonstrate that, as with aspirin, formation of 15-epi-lipoxins may underlie some of the beneficial actions of statins. Studies from Birnbaum et al. demonstrate that atorvastatin promotes the myocardial generation of 15-epi-LXA4 via S-nitrosylation of COX-289. Similar to aspirin-acetylation of COX-2, S-nitrosylated COX-2 produces 15R-HETE, which is converted by leukocyte 5-LOX to generate 15-epi-LXA4 (Figure 3). It was further elucidated that the anti-diabetic thiazolidinedione (TZD), pioglitazone, also promotes the generation of 15-epi-lipoxins in the myocardium and is additive when given together with statins89. COX-2 and 5-LOX co-precipitate in adult rat hearts after treatment with these commonly-used therapeutics90. In isolated adult rat cardiac myocytes, 5-LOX cellular distribution was regulated by statin and TZD treatment, and it was proposed that protein kinase A-dependent phosphorylation of 5-LOX induced by these therapeutics promotes its association with COX-2 to generate 15-epi-lipoxins, whereas in absence of phosphorylation, 5-LOX associates with membranous cytosolic phospholipase A2 to promote generation of leukotrienes90. Thus, these findings illustrate the delicate balance between anti-inflammatory-pro-resolving LM pathways and suggest that commonly used therapeutics may exert anti-inflammatory effects and potentially pro-resolving actions via the regulation of LM biosynthesis.

The enhanced formation of 15-epi-LXA4 by statins was recently confirmed and extended in a report showing that lovastatin promotes 15-epi-LXA4 formation and coincides with protection from murine lung inflammation91. It is noteworthy that potential adverse interactions can occur when COX-2 is both acetylated and S-nitrosylated, in that the activity of COX-2 in promoting 15-epi-LXA4 formation is inhibited92. Given that many cardiovascular disease patients are on both anti-platelet therapy and cholesterol-lowering therapy, further studies on the impact of this combination therapy on inflammation-resolution pathways will be important. It remains of interest whether these results, from both in vitro and in vivo studies, translate to humans. It is likely that this mechanism will also impact the biosynthesis of epimeric forms of resolvins.

Vascular actions of pro-resolving lipid mediators

Lipoxins and resolvins each exhibit direct actions on endothelial cells and regulate leukocyte:endothelial interactions in isolated cells and in vivo (Figure 4). Recent evidence demonstrates that receptors for these mediators, namely ALX and GPR32, are expressed on human endothelial cells29, 63. Lipoxins directly stimulate the endothelial production of vasoprotective and anti-thrombotic mediators, NO and prostacyclin (PGI2)78, 93. Of interest, aspirin-stimulated NO production was found to be dependent on the formation of 15-epi-lipoxin A4 in vivo. Notably, the anti-inflammatory actions of aspirin are dependent on both constitutive and inducible nitric oxide synthase (eNOS and iNOS)-derived NO, and both aspirin and 15-epi-LXA4 have reduced effects on leukocyte:endothelial interactions in eNOS and iNOS knock-out mice78. These results provide further support that 15-epi-lipoxin production underlies some of the beneficial cardiovascular effects of aspirin treatment. Lastly, 15-epi-lipoxin potently reduces the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in endothelial cells by preventing NADPH-oxidase activation94. Recently, we determined that resolvin D2 (RvD2) directly stimulates the endothelial production of NO and that RvD2 potently reduces leukocyte infiltration in a murine model of peritonitis in an eNOS-dependent manner62. Leukocyte adhesion to post-capillary venules was largely abolished by RvD2, as assessed by intravital microscopy, and this is also partially dependent on endogenous NO production, as a non-selective NOS inhibitor reversed this effect62.

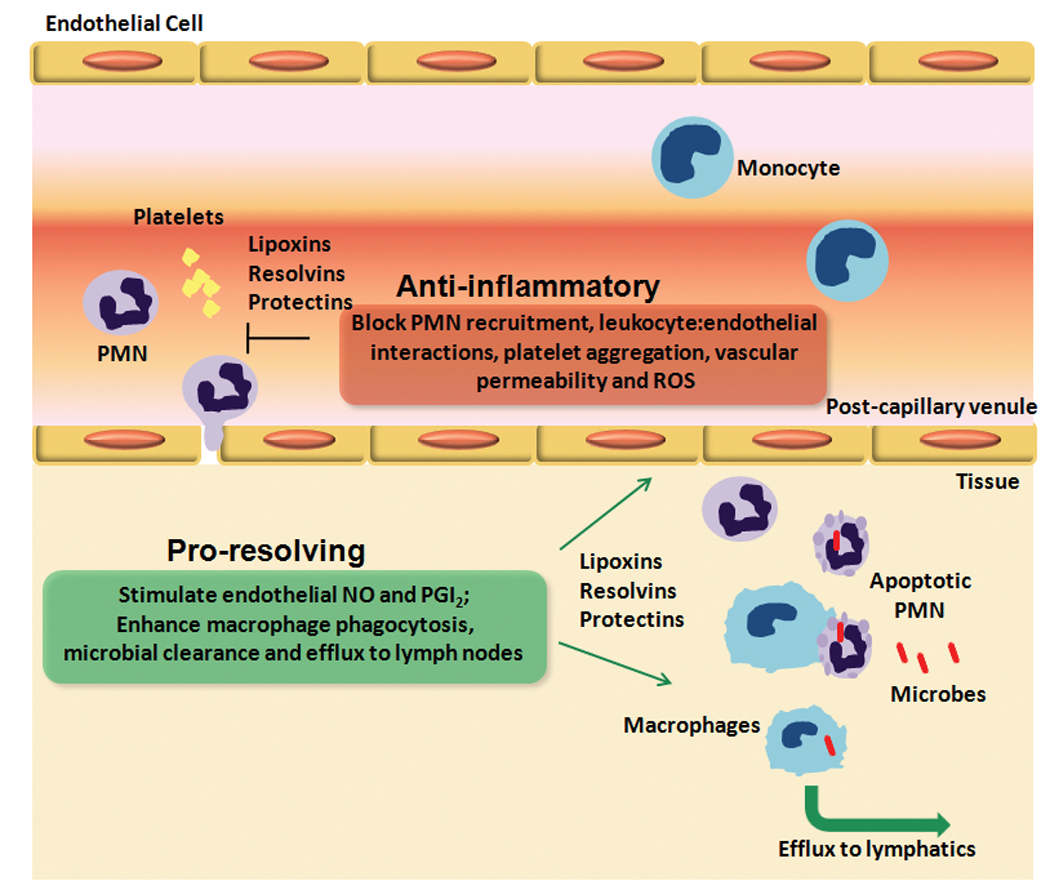

Figure 4. Novel anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving actions of lipoxins, resolvins and protectins in the vasculature.

Tissue injury and microbial invasion precipitates the release of endogenous chemical mediators that increase vascular permeability and promote leukocyte chemotaxis in post-capillary venules, which characterizes the initiation of the acute inflammatory response. After killing the invading microbes, PMN undergo apoptosis and must be cleared by macrophages to allow for tissue homeostasis to be restored. During the time course of the acute inflammatory response, endogenous lipid mediators, such as the lipoxins (LX), resolvins (Rv) and protectins are generated and act locally to stop further vascular permeability and leukocyte chemotaxis, and promote the formation of anti-adhesive and anti-thrombotic mediators, NO and prostacyclin (PGI2). These novel lipid mediators also stimulate phagocytosis and clearance of apoptotic PMN and microbes. Ungoverned activation of leukocytes and endothelial cells can lead to extracellular release of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and excessive leukocyte recruitment and/or altered clearance, which are prominent characteristics of chronic inflammatory diseases. (Illustration Credit: Cosmocyte/Cameron Slayden)

In addition to regulating the vascular production of NO and prostacyclin, 15-epi-lipoxins have been shown to underlie aspirin-induced heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) expression in endothelial cells. A stable analog of 15-epi-LXA4, denoted ATL-1, directly stimulates HO-1 expression in isolated human endothelial cells to a similar extent as aspirin alone95. These effects of ATL-1 were shown to be receptor-dependent and translated to reduced surface expression of VCAM-1 in a HO-1-dependent manner95. Lastly, recent evidence indicates that both lipoxins and resolvins have direct actions on vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC). Receptors for both LXA4 and RvE1, ALX and ChemR23, respectively, were identified on human saphenous vein SMC. Both RvE1 and 15-epi-lipoxin A4 counter-regulate platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-stimulated VSMC migration in a dose-dependent manner and decrease PDGF receptor phosphorylation96. Thus, these and related results suggest that pro-resolution LM may have multiple diverse and protective actions beyond myeloid cells. It will be important to determine if these novel actions of pro-resolution lipid mediators translate into protective actions in complex cardiovascular pathologies.

Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is widely viewed as a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by the excessive recruitment and activation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells, such as monocytes and T-cells18. Monocytes differentiate into macrophages within the plaque milieu and attempt to clear excess oxidized lipoproteins and cholesterol from the tissue. This precipitates the generation of lipid-laden foam cells that fail to clear from the plaque, continue to secrete pro-inflammatory mediators and eventually undergo post-apoptotic secondary necrosis17. Emerging evidence highlights that atherosclerosis could be viewed as a state of failed resolution of inflammation17. Indeed, recent results demonstrate that peripheral artery disease patients have a defect in generation of pro-resolution LM, 15-epi-LXA496. Given the indispensible role of macrophage efferocytosis in resolution, new evidence suggests that defective clearance of plaque macrophages may underlie the progression of advanced atherosclerotic lesions, characterized by macrophage necrosis. Li et al. demonstrated that peritoneal macrophages isolated from obese-diabetic mice crossed with LDL-receptor deficient mice (LDLR−/−) display defects in their ability to phagocytose apopotic cells16. Moreover, defective phagocytosis and clearance of apoptotic cells was observed in advanced atherosclerotic lesions from these mice. Interestingly, saturated fatty acids (palmitic and stearic) were increased in obese mice relative to endogenous omega-3s and were implicated in defective macrophage efferocytosis. Accordingly, supplementation of omega-3s, EPA and DHA, reversed deficits in macrophage efferocytosis in obese/LDLR−/− mice16. These studies highlight that progression of chronic inflammatory diseases could result in part because of altered resolution and implicates a role for endogenous lipid mediator pathways.

In accordance with the view that altered resolution contributes to atherogenesis, mice lacking both 12/15-LOX and apoE display exacerbated atherosclerotic lesion formation compared to apoE-null mice97. Similarly, targeted macrophage-specific overexpression of 12/15-LOX protected from lesion development. Importantly, 12/15-LOX gene dosage correlated with LXA4 formation in isolated macrophages, as well as the production of 17-hydroxydocosahexaenoic acid, a marker of the D-series resolvin biosynthetic pathway. Both lipoxins and resolvins display potent actions on isolated macrophages and endothelial cells, regulating production of pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines and adhesion receptors (VCAM-1 and P-selectin)97. Notably, LXA4 and RvD1 each enhance macrophage phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. These results corroborate earlier findings in rabbits demonstrating the atheroprotective effect of macrophage-specific transgenic overexpression of 15-LOX 98. The anti-inflammatory pro-resolving role of this pathway was recently independently confirmed99–101.

Containing & clearing microbes

Prevalence of polymicrobial sepsis is increasing and mortality rates associated with septic shock remain as high as 20 to 60% despite clinical efforts to control infection102. Although sepsis precipitates a robust systemic inflammatory response, anti-inflammatory therapies have largely failed in human studies in part due to sustained immunosuppression and bacterial proliferation102. Infection progresses rapidly in sepsis and must be contained by phagocytes to prevent bacterial proliferation, multiple-organ failure and ultimately, death. Thus, therapeutic strategies to control excessive inflammation without promoting immune suppression are warranted. Of note, omega-3 supplementation has protective actions in animal models of sepsis and blunts the inflammatory response to endotoxin in humans, although the mechanistic basis underlying this protection is not known103–105. Using a widely established murine model of polymicrobial sepsis that most closely resembles the human clinical picture, namely cecal ligation and puncture (CLP), we recently determined that the bioactive DHA-derived mediator RvD2 enhances survival of septic mice62. Pre- or post-operative treatment with synthetic RvD2 at nanogram doses reduced excessive leukocyte infiltration, while enhancing phagocyte-dependent bacterial clearance to inguinal lymph nodes. Both local and systemic bacteremia were largely blunted with RvD2 treatment, which protected mice from the systemic ‘cytokine storm’ and CLP-induced hypothermia. Notably, RvD2 treatment blunted systemic increases in both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-17, IL-1β and IL-10, which have been documented to have detrimental actions in sepsis106–108. Importantly, RvD2 also regulated the production of pro-inflammatory eicosanoids, such as PGE2 and LTB4. Corroboratory results were obtained with human PMN in vitro where RvD2 (nanomolar range) enhanced phagocytosis and killing of E.coli. These results further demonstrate the potent and distinct anti-inflammatory vs. pro-resolution actions of RvD2 and highlight that resolvins may represent a new class of therapeutics that are not immunosuppressive, but rather stimulate resolution of complex disease pathologies. Along these lines, RvE1 also displays anti-infective actions, enhancing clearance of bacteria from mouse lungs in a model of pneumonia, leading to increased survival109. Thus, these novel mediators display potent anti-inflammatory, anti-fibrotic, and recently demonstrated anti-infective actions in several widely used experimental models of inflammation and in human cells.

Angiogenesis

Vessel sprouting induced by mitogenic stimuli, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and fibroblast growth factor (FGF), plays an important role in wound healing, recovery from myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury, and organ regeneration110. In contrast, pathologic angiogenesis, as occurs during retinopathy and tumor growth, can be detrimental if not properly regulated110. Lipid mediators are key players in angiogenesis, with pro-inflammatory eicosanoids such as 12-HETE and prostaglandins (PGE2) promoting VEGF-stimulated angiogenesis111, 112. Like most biological processes, angiogenesis is tightly controlled by both positive and negative inputs and, while multiple chemical mediators have been shown to operate in this regard, we have recently learned that lipoxins and resolvins also regulate pathologic angiogenesis. In isolated human endothelial cells, lipoxins and their AT-epimers regulate VEGF, as well as cysteinyl leukotriene (LTD4)-stimulated migration and proliferation113–115. Godson et al. elucidated the mechanistic basis for this regulation and found that LXA4 regulates VEGF receptor-2 phosphorylation and downstream signaling115. This concept of growth factor receptor trans-inhibition was extended to other growth factor receptors, including PDGF-R-β in mesangial cells85. These potent actions of lipoxins were validated in vivo, where 15-epi-lipoxin stable analog (ATL-1) blocked angiogenesis in a granuloma model of inflammatory angiogenesis113. Gronert et al. demonstrated the role of endogenous lipoxin circuits in protecting from pathologic neovascularization induced by corneal injury100. Both the murine homolog of the lipoxin receptor and 15-LOX were upregulated during corneal injury, and genetic ablation of either 15-LOX or 5-LOX (both enzymes involved in lipoxin biosynthesis) exacerbated pathologic neovascularization and correlated with increased VEGF-A and VEGF-3 receptor expression. Along these lines, topical administration of synthetic lipoxins decreases VEGF-A expression and protects from pathologic angiogenesis100.

In addition to the role of AA-derived eicosanoids in regulating angiogenesis, recent evidence also indicates a protective role for omega-3-derived LM in pathologic angiogenesis. Transgenic mice overexpressing the fat-1 gene (vida supra), are protected from hypoxia-induced neovascularization52. Interestingly, resolvins are biosynthesized in fat-1 transgenic mice and administration of synthetic resolvins protect from pathologic neovascularization52. The protective actions of resolvins in this context were mediated in part through the direct regulation of retinal TNF-α production. These results were extended in further studies which showed that both lipoxins and resolvins modulate leukocyte infiltration into injured corneas, regulate pro-inflammatory cytokine generation, VEGF-A production, and decrease angiogenesis116. Importantly, receptors for both LXA4 and RvE1, ALX and ChemR23, are expressed in epithelial cells, stromal keratinocytes and infiltrated CD11b+ cells116. Overall, these results suggest that lipoxins and resolvins have diverse protective actions on multiple cell types and endogenous pro-resolution circuits protect against pathologic angiogenesis.

Ischemia-reperfusion injury

Several recent reports demonstrate that pro-resolution LM elicit organ-protective actions during ischemia/reperfusion. In the kidney, reperfusion following an ischemic insult results in increased circulating DHA and correlates with local production of D-series resolvins, including RvD272. This is consistent with recent results demonstrating that free plasma DHA is rapidly delivered to inflammatory sites for local generation of resolvins117. Synthetic resolvins largely abolish leukocyte infiltration into reperfused kidneys and protect from second-organ reperfusion injury in a murine model of hind-limb ischemia72, 117. Importantly, the protective actions of synthetic resolvins and their stable analogs are retained after therapeutic administration (i.e. after the initiation of reperfusion). The endogenous protective role of pro-resolution mediators was demonstrated in mice lacking the murine homolog of the lipoxin A4 receptor (ALX/FPR2), in which ischemia/reperfusion resulted in excessive leukocyte adhesion and emigration in the mesenteric microcirculation41. Of note, in addition to regulating excessive leukocyte-mediated tissue injury in response to reperfusion, pro-resolution LM also reduce organ fibrosis72, 85. Recently, it was shown that RvE1 stimulates phosphorylation of eNOS and Akt, and prevents apoptosis in cardiac myocytes exposed to hypoxia/re-oxygenation by attenuating the level of activated caspase-3. These direct actions were demonstrated in vivo where RvE1 decreased infarct size in a rat model of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury118. Of note, these protective actions of RvE1 are dependent on activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and are consistent with a recent report documenting transactivation of EGFR by RvE1 in corneal epithelial cells118, 119.

Obesity and diabetes: Lipid mediator interplay

Obesity is one of the most robust risk factors for the development of type II diabetes, and chronic low-grade inflammation is currently held to be a prominent link between the two syndromes120. Given the indispensible role of LM in orchestrating macrophage-dependent inflammatory responses, it is not surprising that operational LM pathways were recently found to play both positive and negative regulatory roles within the context of obesity-induced diabetes. Clària et al. recently found that the leukotriene pathway plays a role in the development of adipose tissue inflammation in experimental obesity121. Enzymes involved in LTB4 biosynthesis, including 5-LOX and 5-LOX activating protein (FLAP), were expressed in adipose tissue, and the level of FLAP increases with high fat feeding. Importantly, receptors for LTB4 (BLT-1 and 2), as well as the cysteinyl leukotrienes (cysLT1 and 2) are expressed in adipocytes and stromal vascular cells. Modulation of the leukotriene biosynthetic pathway with a FLAP inhibitor decreased systemic pro-inflammatory cytokines, adipose tissue macrophage content and systemic insulin resistance121. In a separate study, omega-3 feeding was protective in obesity-induced inflammation and associated with resolvin biosynthesis in adipose tissue122. Synthetic RvE1 increased mRNA expression of genes known to be protective against systemic insulin resistance, such as adiponectin, PPARγ and insulin-receptor substrate-1122.

Summary and Future Directions

Pro-resolving LM including the lipoxins, resolvins, protectins and recently identified maresins, represent a new genus of endogenous LM that carry out mult-level anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution actions to hasten the return to homeostasis. These novel mediators possess unique and specific protective functions demonstrated in animal models of acute and chronic diseases, and also have potent actions on, and are biosynthesized by, human cells. The discovery of these opens up entirely new terrain for therapeutics based on endogenous biotemplates for treating inflammatory diseases by stimulating resolution. Although these new families of autacoids share many protective actions, an appreciation of their distinct, targeted roles in regulating local diverse events in resolution is rapidly emerging.

In ongoing studies, it will be important to elucidate how pro-resolution pathways are modulated with the progression of chronic diseases and the impact of blocking these pathways in humans. Although both aspirin and statins can promote the formation of endogenous protective LM and thereby exert anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving actions, other commonly used therapeutics can delay resolution15. In summation, this new area of ‘resolution pharmacology’ is likely to lead to better targeted approaches to treat inflammatory diseases without precipitating sustained immunosuppresion that may be relevant in vascular medicine.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mary H. Small for expert assistance in manuscript preparation.

Sources of funding

Results from the C.N.S. lab reviewed here were supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants GM38765, DK074448 and DE019938. The authors also acknowledge the support of the NIH Diabetes and Obesity Center 1P20RR024489 (M.S.).

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AA

arachidonic acid

- EPA

eicosapentaenoic acid

- DHA

docosahexaenoic acid

- LOX

lipoxygenase

- LM

lipid mediators

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- LXA4

5S,6R,15S-trihydroxy-7,9,13-trans-11-cis-eicosatetraenoic acid

- ATL

aspirin-triggered LXA4, 5S,6R,15R-trihydroxy-7,9,13-trans-11-cis-eicosatetraenoic acid

- PMN

polymorphonuclear neutrophils

- NPD1/PD1

10R,17S-dihydroxy-docosa-4Z,7Z,11E,13E,15Z,19Z-hexaenoic acid

- Rv

resolvin

- RvD1

resolvin D1, 7S,8R,17S-trihydroxy-docosa-4Z,9E,11E,13Z,15E,19Z-hexaenoic acid

- AT-RvD1

aspirin-triggered-RvD1, 7S,8R,17R-trihydroxy-docosa-4Z,9E,11E,13Z,15E,19Z-hexaenoic acid

- RvD2

resolvin D2, 7S,16R,17S-trihydroxy-docosa-4Z,8E,10Z,12E,14E,19Z-hexaenoic acid

- AT-RvD2

aspirin-triggered RvD2, 7S,16R,17R-trihydroxy-docosa-4Z,8E,10Z,12E,14E,19Z-hexaenoic acid

- RvE1

resolvin E1, 5S,12R,18R-trihydroxy-eicosa-6Z,8E,10E,14Z,16E-pentaenoic acid

- MaR1

maresin 1, 7,14-dihydroxydocosa-4Z,8,10,12,16Z,19Z-hexaenoic acid

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

C.N.S. is inventor on patents covering structural elucidation and composition of matter of the resolvins and protectins, as well as their uses. These patents are assigned to Brigham and Women’s Hospital and are licensed for clinical development to Resolvyx Pharmaceutical Company. C.N.S. is a founder and retains founder stock. M.S. has no disclosures.

References

- 1.Serhan CN, Savill J. Resolution of inflammation: The beginning programs the end. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1191–1197. doi: 10.1038/ni1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braunwald E. Biomarkers in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2148–2159. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0800239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellis CR, Di Salvo T. Myocarditis: Basic and clinical aspects. Cardiol Rev. 2007;15:170–177. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e31806450c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rocha VZ, Libby P. Obesity, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6:399–409. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dinarello CA. Anti-inflammatory agents: Present and future. Cell. 2010;140:935–950. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flower RJ. The development of cox2 inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:179–191. doi: 10.1038/nrd1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor PC, Feldmann M. Anti-tnf biologic agents: Still the therapy of choice for rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2009;5:578–582. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perretti M, D'Acquisto F. Annexin a1 and glucocorticoids as effectors of the resolution of inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:62–70. doi: 10.1038/nri2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patrono C, Rocca B. Aspirin: Promise and resistance in the new millennium. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:s25–s32. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.160481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Funk CD, FitzGerald GA. Cox-2 inhibitors and cardiovascular risk. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2007;50:470–479. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e318157f72d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nathan C, Ding A. Nonresolving inflammation. Cell. 2010;140:871–882. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar V, Abbas A, Fausto N. Robbins and cotran pathologic basis of disease. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Serhan CN. Resolution phase of inflammation: Novel endogenous anti-inflammatory and proresolving lipid mediators and pathways. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:101–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rossi AG, Sawatzky DA, editors. The resolution of inflammation. Basel: Birkhäuser Verlag AG; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serhan CN, Brain SD, Buckley CD, Gilroy DW, Haslett C, O'Neill LA, Perretti M, Rossi AG, Wallace JL. Resolution of inflammation: State of the art, definitions and terms. FASEB J. 2007;21:325–332. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7227rev. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li S, Sun Y, Liang CP, Thorp EB, Han S, Jehle AW, Saraswathi V, Pridgen B, Kanter JE, Li R, Welch CL, Hasty AH, Bornfeldt KE, Breslow JL, Tabas I, Tall AR. Defective phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by macrophages in atherosclerotic lesions of ob/ob mice and reversal by a fish oil diet. Circ Res. 2009;105:1072–1082. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.199570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tabas I. Macrophage death and defective inflammation resolution in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:36–46. doi: 10.1038/nri2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansson GK, Libby P. The immune response in atherosclerosis: A double-edged sword. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:508–519. doi: 10.1038/nri1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samuelsson B, Dahlen SE, Lindgren JA, Rouzer CA, Serhan CN. Leukotrienes and lipoxins: Structures, biosynthesis, and biological effects. Science. 1987;237:1171–1176. doi: 10.1126/science.2820055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flower RJ. Prostaglandins, bioassay and inflammation. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147 Suppl 1:S182–S192. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levy BD, Clish CB, Schmidt B, Gronert K, Serhan CN. Lipid mediator class switching during acute inflammation: Signals in resolution. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:612–619. doi: 10.1038/89759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Serhan CN, Clish CB, Brannon J, Colgan SP, Chiang N, Gronert K. Novel functional sets of lipid-derived mediators with antiinflammatory actions generated from omega-3 fatty acids via cyclooxygenase 2-nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and transcellular processing. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1197–1204. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.8.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawrence T, Fong C. The resolution of inflammation: Anti-inflammatory roles for nf-kappab. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:519–523. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bannenberg GL, Chiang N, Ariel A, Arita M, Tjonahen E, Gotlinger KH, Hong S, Serhan CN. Molecular circuits of resolution: Formation and actions of resolvins and protectins. J Immunol. 2005;174:4345–4355. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwab JM, Chiang N, Arita M, Serhan CN. Resolvin e1 and protectin d1 activate inflammation-resolution programmes. Nature. 2007;447:869–874. doi: 10.1038/nature05877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Serhan CN, Hong S, Gronert K, Colgan SP, Devchand PR, Mirick G, Moussignac RL. Resolvins: A family of bioactive products of omega-3 fatty acid transformation circuits initiated by aspirin treatment that counter proinflammation signals. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1025–1037. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilroy DW, Colville-Nash PR, Willis D, Chivers J, Paul-Clark MJ, Willoughby DA. Inducible cyclooxygenase may have anti-inflammatory properties. Nat Med. 1999;5:698–701. doi: 10.1038/9550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Serhan CN, Chiang N, Van Dyke TE. Resolving inflammation: Dual anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:349–361. doi: 10.1038/nri2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chiang N, Arita M, Serhan CN. Anti-inflammatory circuitry: Lipoxin, aspirin-triggered lipoxins and their receptor alx. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2005;73:163–177. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Claria J, Serhan CN. Aspirin triggers previously undescribed bioactive eicosanoids by human endothelial cell-leukocyte interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:9475–9479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Claria J, Lee MH, Serhan CN. Aspirin-triggered lipoxins (15-epi-lx) are generated by the human lung adenocarcinoma cell line (a549)-neutrophil interactions and are potent inhibitors of cell proliferation. Mol Med. 1996;2:583–596. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morris T, Stables M, Colville-Nash P, Newson J, Bellingan G, de Souza PM, Gilroy DW. Dichotomy in duration and severity of acute inflammatory responses in humans arising from differentially expressed proresolution pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:8842–8847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000373107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morris T, Stables M, Hobbs A, de Souza P, Colville-Nash P, Warner T, Newson J, Bellingan G, Gilroy DW. Effects of low-dose aspirin on acute inflammatory responses in humans. J Immunol. 2009;183:2089–2096. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scalia R, Gefen J, Petasis NA, Serhan CN, Lefer AM. Lipoxin a4 stable analogs inhibit leukocyte rolling and adherence in the rat mesenteric microvasculature: Role of p-selectin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:9967–9972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Godson C, Mitchell S, Harvey K, Petasis NA, Hogg N, Brady HR. Cutting edge: Lipoxins rapidly stimulate nonphlogistic phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils by monocyte-derived macrophages. J Immunol. 2000;164:1663–1667. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Machado FS, Johndrow JE, Esper L, Dias A, Bafica A, Serhan CN, Aliberti J. Anti-inflammatory actions of lipoxin a4 and aspirin-triggered lipoxin are socs-2 dependent. Nat Med. 2006;12:330–334. doi: 10.1038/nm1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parameswaran K, Radford K, Fanat A, Stephen J, Bonnans C, Levy BD, Janssen LJ, Cox PG. Modulation of human airway smooth muscle migration by lipid mediators and th-2 cytokines. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;37:240–247. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0172OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gronert K, Martinsson-Niskanen T, Ravasi S, Chiang N, Serhan CN. Selectivity of recombinant human leukotriene d(4), leukotriene b(4), and lipoxin a(4) receptors with aspirin-triggered 15-epi-lxa(4) and regulation of vascular and inflammatory responses. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:3–9. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63937-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ye RD, Boulay F, Wang JM, Dahlgren C, Gerard C, Parmentier M, Serhan CN, Murphy PM. International union of basic and clinical pharmacology. Lxxiii. Nomenclature for the formyl peptide receptor (fpr) family. Pharmacol Rev. 2009;61:119–161. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.001578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Devchand PR, Arita M, Hong S, Bannenberg G, Moussignac RL, Gronert K, Serhan CN. Human alx receptor regulates neutrophil recruitment in transgenic mice: Roles in inflammation and host defense. FASEB J. 2003;17:652–659. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0770com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dufton N, Hannon R, Brancaleone V, Dalli J, Patel HB, Gray M, D'Acquisto F, Buckingham JC, Perretti M, Flower RJ. Anti-inflammatory role of the murine formyl-peptide receptor 2: Ligand-specific effects on leukocyte responses and experimental inflammation. J Immunol. 2010;184:2611–2619. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simopoulos AP. Omega-3 fatty acids in the prevention-management of cardiovascular disease. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1997;75:234–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burr ML, Fehily AM, Gilbert JF, Rogers S, Holliday RM, Sweetnam PM, Elwood PC, Deadman NM. Effects of changes in fat, fish, and fibre intakes on death and myocardial reinfarction: Diet and reinfarction trial (dart) Lancet. 1989;2:757–761. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90828-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dietary supplementation with n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and vitamin e after myocardial infarction: Results of the gissi-prevenzione trial. Gruppo italiano per lo studio della sopravvivenza nell'infarto miocardico. Lancet. 1999;354:447–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tavazzi L, Maggioni AP, Marchioli R, Barlera S, Franzosi MG, Latini R, Lucci D, Nicolosi GL, Porcu M, Tognoni G. Effect of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in patients with chronic heart failure (the gissi-hf trial): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:1223–1230. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61239-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roberts LJ, 2nd, Fessel JP. The biochemistry of the isoprostane, neuroprostane, and isofuran pathways of lipid peroxidation. Chem Phys Lipids. 2004;128:173–186. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arita M, Bianchini F, Aliberti J, Sher A, Chiang N, Hong S, Yang R, Petasis NA, Serhan CN. Stereochemical assignment, antiinflammatory properties, and receptor for the omega-3 lipid mediator resolvin e1. J Exp Med. 2005;201:713–722. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cash JL, Hart R, Russ A, Dixon JP, Colledge WH, Doran J, Hendrick AG, Carlton MB, Greaves DR. Synthetic chemerin-derived peptides suppress inflammation through chemr23. J Exp Med. 2008;205:767–775. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ohira T, Arita M, Omori K, Recchiuti A, Van Dyke TE, Serhan CN. Resolvin e1 receptor activation signals phosphorylation and phagocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:3451–3461. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.044131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arita M, Ohira T, Sun YP, Elangovan S, Chiang N, Serhan CN. Resolvin e1 selectively interacts with leukotriene b4 receptor blt1 and chemr23 to regulate inflammation. J Immunol. 2007;178:3912–3917. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arita M, Yoshida M, Hong S, Tjonahen E, Glickman JN, Petasis NA, Blumberg RS, Serhan CN. Resolvin e1, an endogenous lipid mediator derived from omega-3 eicosapentaenoic acid, protects against 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:7671–7676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409271102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Connor KM, SanGiovanni JP, Lofqvist C, Aderman CM, Chen J, Higuchi A, Hong S, Pravda EA, Majchrzak S, Carper D, Hellstrom A, Kang JX, Chew EY, Salem N, Jr, Serhan CN, Smith LE. Increased dietary intake of omega-3-polyunsaturated fatty acids reduces pathological retinal angiogenesis. Nat Med. 2007;13:868–873. doi: 10.1038/nm1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hasturk H, Kantarci A, Ohira T, Arita M, Ebrahimi N, Chiang N, Petasis NA, Levy BD, Serhan CN, Van Dyke TE. Rve1 protects from local inflammation and osteoclast- mediated bone destruction in periodontitis. FASEB J. 2006;20:401–403. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4724fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dona M, Fredman G, Schwab JM, Chiang N, Arita M, Goodarzi A, Cheng G, von Andrian UH, Serhan CN. Resolvin e1, an epa-derived mediator in whole blood, selectively counter regulates leukocytes and platelets. Blood. 2008;112:848–855. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-122598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tjonahen E, Oh SF, Siegelman J, Elangovan S, Percarpio KB, Hong S, Arita M, Serhan CN. Resolvin e2: Identification and anti-inflammatory actions: Pivotal role of human 5-lipoxygenase in resolvin e series biosynthesis. Chem Biol. 2006;13:1193–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stirban A, Nandrean S, Gotting C, Tamler R, Pop A, Negrean M, Gawlowski T, Stratmann B, Tschoepe D. Effects of n-3 fatty acids on macro- and microvascular function in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:808–813. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.De Caterina R, Cybulsky MA, Clinton SK, Gimbrone MA, Jr, Libby P. Omega-3 fatty acids and endothelial leukocyte adhesion molecules. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1995;52:191–195. doi: 10.1016/0952-3278(95)90021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.De Caterina R, Liao JK, Libby P. Fatty acid modulation of endothelial activation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:213S–223S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.1.213S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Massaro M, Habib A, Lubrano L, Del Turco S, Lazzerini G, Bourcier T, Weksler BB, De Caterina R. The omega-3 fatty acid docosahexaenoate attenuates endothelial cyclooxygenase-2 induction through both nadp(h) oxidase and pkc epsilon inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15184–15189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510086103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hong S, Gronert K, Devchand PR, Moussignac RL, Serhan CN. Novel docosatrienes and 17s-resolvins generated from docosahexaenoic acid in murine brain, human blood, and glial cells. Autacoids in anti-inflammation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14677–14687. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300218200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sun YP, Oh SF, Uddin J, Yang R, Gotlinger K, Campbell E, Colgan SP, Petasis NA, Serhan CN. Resolvin d1 and its aspirin-triggered 17r epimer. Stereochemical assignments, anti-inflammatory properties, and enzymatic inactivation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:9323–9334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609212200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Spite M, Norling LV, Summers L, Yang R, Cooper D, Petasis NA, Flower RJ, Perretti M, Serhan CN. Resolvin d2 is a potent regulator of leukocytes and controls microbial sepsis. Nature. 2009;461:1287–1291. doi: 10.1038/nature08541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Krishnamoorthy S, Recchiuti A, Chiang N, Yacoubian S, Lee CH, Yang R, Petasis NA, Serhan CN. Resolvin d1 binds human phagocytes with evidence for proresolving receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:1660–1665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907342107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marcheselli VL, Hong S, Lukiw WJ, Tian XH, Gronert K, Musto A, Hardy M, Gimenez JM, Chiang N, Serhan CN, Bazan NG. Novel docosanoids inhibit brain ischemia-reperfusion-mediated leukocyte infiltration and pro-inflammatory gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:43807–43817. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305841200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mukherjee PK, Marcheselli VL, Serhan CN, Bazan NG. Neuroprotectin d1: A docosahexaenoic acid-derived docosatriene protects human retinal pigment epithelial cells from oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8491–8496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402531101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]