Correct splicing of U12 introns is essential for constitutive and regulated gene expression in eukaryotes. This study provides evidence that U11/U12-31K, a U12-type spliceosomal protein in Arabidopsis thaliana, is an RNA chapereone that is indispensible for proper U12 intron splicing and for normal growth and development of plants.

Abstract

U12 introns are removed from precursor-mRNA by a U12 intron-specific spliceosome that contains U11 and U12 small nuclear ribonucleoproteins. Although several proteins unique to the U12-type spliceosome have been identified, the manner by which they affect U12-dependent intron splicing as well as plant growth and development remain largely unknown. Here, we assessed the role of U11/U12-31K, a U12-type spliceosomal protein in Arabidopsis thaliana. T-DNA–tagged homozygote lines for U11/U12-31K could not be obtained, and heterozygote mutants were defective for seed maturation, indicating that U11/U12-31K is essential for the normal development of Arabidopsis. Knockdown of U11/U12-31K by artificial microRNA caused a defect in proper U12 intron splicing, resulting in abnormal stem growth and development of Arabidopsis. This defect in proper splicing was not restricted to specific U12-type introns, but most U12 intron splicing was influenced by U11/U12-31K. The stunted inflorescence stem growth was recovered by exogenously applied gibberellic acid (GA), but not by cytokinin, auxin, or brassinosteroid. GA metabolism-related genes were highly downregulated in U11/U12-31K knockdown plants. Importantly, U11/U12-31K was determined to harbor RNA chaperone activity. We propose that U11/U12-31K is an RNA chapereone that is indispensible for proper U12 intron splicing and for normal growth and development of plants.

INTRODUCTION

Precursor-mRNA splicing, the basic mechanism of which is similar in all eukaryotes, is an indispensible step for constitutive and regulated gene expression in eukaryotes. U2-dependent introns (U2 introns) are the most common type of intron, whereas U12-dependent introns (U12 introns) are rare. U12 introns have been identified in a wide range of eukaryotes (Russell et al., 2006) and constitute ~0.35% of all introns in human and mouse and 0.17% of all introns in Arabidopsis thaliana (Levine and Durbin, 2001; Zhu and Brendel, 2003; Sheth et al., 2006; Alioto, 2007). Although U12-type introns are significantly less frequent than U2-type introns, their importance is substantial in many organisms. Loss-of-function of either the U12 or U6atac small nuclear RNA (snRNA) gene causes defects in embryonic development in Drosophila melanogaster and zebra fish (Danio rerio; Otake et al., 2002; König et al., 2007), and the RNA interference–mediated knockdown of U11/U12-specific proteins reduces the viability of HeLa cells (Will et al., 2004). U12 intron splicing has also been implicated in nonsense-mediated mRNA decay, which is important for destroying transcripts bearing premature termination codons (Zhu and Brendel, 2003; Hirose et al., 2004). Splicing of rare U12-type introns is catalyzed by the minor spliceosome (Wu et al., 1996; Burge et al., 1998; Zhu and Brendel, 2003), in contrast with the vast majority of U2-type introns, which are catalyzed by the major spliceosome. Although the overall assembly and splicing process of the minor spliceosome is analogous to that of the major spliceosome, there is one major difference. In contrast with the U1 and U2 small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs), the U11 and U12 snRNPs form a stable U11/U12 di-snRNP complex that recognizes the 5′ splice site and branchpoint site during minor spliceosome formation (Wassarman and Steitz, 1992; Frilander and Steitz, 1999). Among the distinct proteins identified in the U11/U12 di-snRNPs, seven unique proteins, denoted 65K, 59K, 48K, 35K, 31K, 25K, and 20K, specifically associate with human U11/U12 di-snRNPs (Schneider et al., 2002; Will et al., 2004). Minor spliceosome-associated proteins were also found to be well conserved in both dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous plants (Will et al., 2004; Lorković et al., 2005; Russell et al., 2006).

Although the significance of many minor spliceosomal proteins has not yet been proven experimentally, we have recently gained insight into the roles of minor spliceosomal proteins. In HeLa cells, U11/U12-59K and U11/U12-65K were found to be integral proteins that bridge U11 snRNP at the 5′ splice site and U12 snRNP at the branchpoint site (Benecke et al., 2005). U11/U12-48K was also shown to interact with the 5′ splice site and U11/U12-59K protein (Turunen et al., 2008), suggesting that these three minor spliceosomal proteins are involved in the formation of the stable U11/U12 di-snRNP complex in animals. However, reports demonstrating the functional roles of minor spliceosomal proteins in plants are limited. Arabidopsis U11/U12-35K, which interacts with cyclophilin, was proposed to facilitate the recognition of the 5′ splice site (Lorković et al., 2004). U11/U12-31K proteins are highly conserved compared with other minor spliceosomal proteins (Will et al., 2004), which is consistent with the notion that they perform important cellular functions. Nevertheless, little is known about the biological roles of U11/U12-31K proteins in both animal and plant species.

RNA–protein and RNA–RNA interactions, which are mainly facilitated by spliceosome-associated RNA binding proteins (RBPs), are required for spliceosome assembly, splicing, and subsequent spliceosome disassembly (Staley and Guthrie, 1998, 1999). RNA must be correctly folded into a splicing-competent conformation for efficient intron splicing, and specific types of RBPs, such as RNA chaperones, are thought to be involved in this process. RNA chaperones resolve misfolded, nonfunctional RNAs into correctly folded, functional forms. Diverse protein families function as RNA chaperones, including cold shock domain proteins, Gly-rich RBPs, histone-like proteins, ribosomal proteins, and viral nucleocapsid (NC) proteins (Jiang et al., 1997; Kim et al., 2007; Rajkowitsch et al., 2007). Viral NC proteins harbor one CCHC-type zinc finger motif, and the RNA chaperone activity of this motif is critical for viral RNA packaging and replication (Williams et al., 2001; Buckman et al., 2003; Heath et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2007). Plant cold shock domain proteins possess one to seven CCHC-type zinc finger motifs and exhibit RNA chaperone activities (Nakaminami et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2007; Park et al., 2009). Since Arabidopsis U11/U12-31K is characterized by the presence of one CCHC-type zinc finger motif, it is likely that this protein has RNA chaperone activity. Here, we present evidence that U11/U12-31K is essential for U12-type intron splicing by functioning as an RNA chaperone and that this U11/U12-31K-dependent U12 splicing is critical for normal plant development.

RESULTS

Characterization of U11/U12-31K in Arabidopsis

Arabidopsis U11/U12-31K shares 62% amino acid sequence identity with its human counterpart (Will et al., 2004). To determine the characteristic features of plant U11/U12-31K proteins, we searched public databases for similar proteins. We found that plant U11/U12-31K proteins are well conserved from mosses to woody plants and that these proteins share over 70% amino acid sequence identity (see Supplemental Figure 1 online). Arabidopsis U11/U12-31K is the homolog of human U11/U12-31K. Note that plant U11/U12-31K proteins have a peptide upstream of the RNA recognition motif in their N-terminal regions (see Supplemental Figure 1 online) that is absent in animal putative orthologs (Will et al., 2004). The length of these additional peptides varies among plant species, being the shortest in moss and the longest in woody plants. Based on primary amino acid sequence data, the N terminus is the most divergent region of plant U11/U12-31K proteins. This suggests that the N-terminal extension plays specific roles in individual plant species (Will et al., 2004).

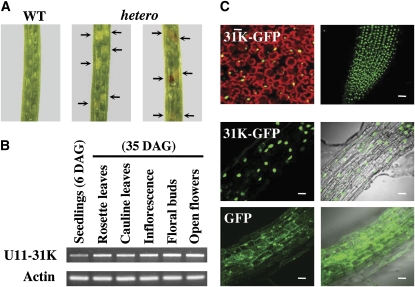

To determine the functional roles of AtU11/U12-31K during plant growth and development, a T-DNA insertion mutant line (WiscDsLox485-488L9) was obtained from the ABRC. The T-DNA was inserted in the coding region of U11/U12-31K, which contains no introns. Efforts to select homozygous mutants from the heterozygous T-DNA insertion plants were unsuccessful. Instead, about one-fourth of the seeds were aborted, presumably due to the presence of homozygous embryos (Figure 1A). This result is the first indication that U11/U12-31K is essential for embryonic development in plants.

Figure 1.

Lethality of Loss-of-Function Mutants and Expression Patterns of Arabidopsis U11/U12-31K.

(A) Siliques of wild-type (WT) and T-DNA–tagged heterozygous mutant (hetero) plants. Aborted or immature seeds are indicated by arrows.

(B) Expression patterns of U11/U12-31K in various tissues at 6 and 35 d after germination (DAG). The experiment was repeated three times using different batches of RNA samples, and similar results were obtained.

(C) Nuclear localization of U11/U12-31K in the leaf (top left) and roots (top right, middle). Bars = 50 μm.

To investigate the expression profile of U11/U12-31K, total RNAs extracted from rosette leaves, cauline leaves, inflorescence stems, floral buds, and flowers were analyzed by RT-PCR. U11/U12-31K was ubiquitously expressed in all organs tested (Figure 1B). Recently, a controversy has emerged regarding the subcellular localization of the minor spliceosome and whether it exists in the nucleus or the cytoplasm (König et al., 2007; Pessa et al., 2008). To determine the subcellular localization of U11/U12-31K, the expression of the green fluorescent protein (GFP)-31K fusion protein was investigated in transgenic Arabidopsis plants via confocal microscopy. Strong GFP signal was detected exclusively in the nucleus (Figure 1C); similarly, human U11/U12-31K concentrates in the nucleus of HeLa cells (Wang et al., 2007). Taken together, these results indicate that U11/U12-31K is a nuclear protein that plays an essential role in the embryonic development of Arabidopsis, consistent with its role in U12-dependent splicing in other organisms.

Arabidopsis U11/U12-31K Is Crucial for Normal Plant Development

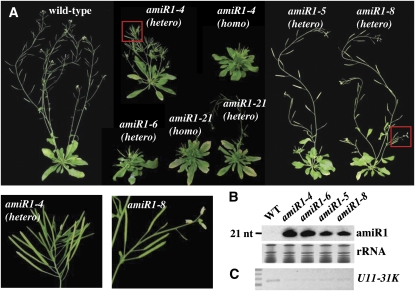

Since homozygous T-DNA insertion embryos are limited in their development, we employed an artificial microRNA (amiRNA)–mediated knockdown strategy to study the functional role of U11/U12-31K in Arabidopsis. amiRNA can efficiently and specifically knock down a particular gene of interest (Schwab et al., 2006). We generated transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing three different amiRNAs, which were designed to target different sites of U11/U12-31K (see Supplemental Tables 1 and 2 online). Among the three generated amiRNA plants, amiRNA2 and amiRNA3 caused only a moderate reduction in U11/U12-31K transcript levels and correspondingly had no effect on plant morphology and development. However, amiRNA1-expressing transgenic plants displayed severe developmental defects, including severely arrested meristem formation (Figure 2A). The 21-mer mature amiRNAs were detected in all transgenic plants (Figure 2B), and RT-PCR confirmed that U11/U12-31K transcript levels in knockdown plants ranged from ~15 to 30% of the levels in wild-type plants (Figure 2C). Multiple independent T1 plants expressing amiRNA1 exhibited pleiotropic phenotypes, including severely arrested meristem formation, serrated leaves, and the production of rosette leaves after bolting. amiRNA1-expressing plants displayed arrested meristems in inflorescence stems, although the stem length of each transgenic plant varied according to the degree of knockdown (Figure 2A; see Supplemental Figure 2 online).

Figure 2.

Phenotypes of miRNA-Mediated U11/U12-31K Knockdown Mutants.

(A) Defects in the growth and development of homozygous (homo) and heterozygous (hetero) transgenic lines of miRNA-mediated knockdown mutants. Abnormal phenotypes highlighted in red boxes are enlarged at the bottom.

(B) Expression of amiRNAs in each transgenic line [amiR1-4 (homo), amiR1-6 (hetero), amiR1-5 (hetero), and amiR1-8 (hetero)] was confirmed by RNA gel blotting. nt, nucleotide; WT, wild type.

(C) Downregulation of U11/U12-31K expression in each transgenic line was confirmed by RT-PCR. The experiment was repeated three times using different batches of RNA samples, and similar results were obtained.

To further examine the transgenic plant phenotypes, we selected two hypermorphic alleles, amiR1-4 and amiR1-6, that produce severely arrested primary inflorescence stems, and two hypomorphic alleles, amiR1-5 and amiR1-8, that produce defects only in the growth of secondary inflorescence stems. It is noteworthy that RNA gel blot analysis revealed that the expression of amiR1-4 and amiR1-6 was stronger than that of amiR1-5 and amiR1-8 (Figure 2B), which is consistent with the observed severity of phenotypes. Although stem growth was strongly inhibited in both amiR1-4 and amiR1-6 plants, there is a major difference. We were not able to select homozygous T3 amiR1-6 transgenic plants from independent T2 plants. All amiR1-6 T3 plants had a 3:1 survival ratio on antibiotic selection media. Moreover, we found that some amiR1-6 T1 plants die and cannot develop beyond vegetative growth, possibly due to strong U11/U12-31K knockdown. This result suggests that strong U11/U12-31K knockdown causes embryonic lethality similar to the effect of the homozygous T-DNA insertion embryo, which further supports the hypothesis that U11/U12-31K plays an essential role in plant development.

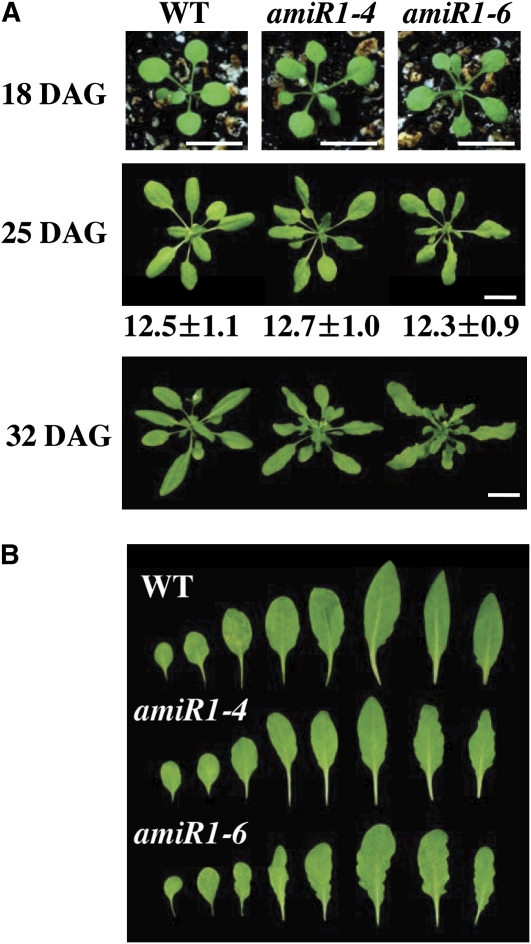

Flowering Time and Leaf Morphology of U11/U12-31K Knockdown Plants

Since mutations in RNA metabolism affect leaf morphology and flowering time (Bezerra et al., 2004; Grigg et al., 2005), we next examined the effect of U11/U12-31K knockdown on flowering time. Since amiRNA1-4 and -6 plants do not often elongate primary inflorescence stems, flowering time was determined when the first floral bud was visible and the first flower opened. U11/U12-31K knockdown plants did not display any noticeable differences in flowering time compared with wild-type plants (Figure 3A). However, after floral transition, the number of rosette leaves was rapidly increased in U11/U12-31K knockdown plants. Homozygous amiRNA1-4 plants exhibited slightly serrated leaf morphologies, whereas heterozygous amiR1-6 plants developed severely serrated leaf morphologies 18 d after germination (Figure 3B). The growth of transgenic plants was not affected by abscisic acid (ABA). Many mutant plants impaired in RNA processing, transport, and degradation display pleiotropic phenotypes, such as serrated leaf formation or altered ABA response and flowering time (Hugouvieux et al., 2001; Bezerra et al., 2004; Lobbes et al., 2006; Laubinger et al., 2008). Therefore, the serrated leaf formation, arrested meristem, and delayed growth of U11/U12-31K knockdown plants in the absence of an altered ABA response or flowering time likely arise from a specific effect of U11/U12-31K knockdown and not from the general effects of impaired RNA metabolism.

Figure 3.

Flowering Time and Leaf Morphology of U11/U12-31K Knockdown Plants.

(A) The number of leaves in wild-type (WT) and knockdown plants (amiR1-4 and amiR1-6) was the same at 18, 25, and 32 d after germination (DAG). The numbers beneath the 25 DAG panel indicate the number of leaves when floral buds appeared. Values are means ± sd (n = 5).

(B) The leaf morphology of wild-type and knockdown plants 18 DAG.

[See online article for color version of this figure.]

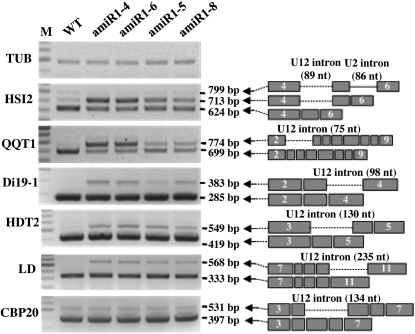

Abnormal Splicing of U12-Introns in U11/U12-31K Knockdown Plants

To ascertain whether the phenotypes observed in U11/U12-31K knockdown plants were due to defects in U12-dependent splicing, we determined the splicing patterns of U12-type introns in each knockdown plant after bolting (~30-d-old plants). Among the 165 U12-type intron-containing genes in Arabidopsis (Alioto, 2007), 20 that have been previously documented or known to be evolutionarily conserved across organisms were randomly chosen and their splicing patterns analyzed. To confirm the effects of U11/U12-31K on U12-dependent splicing, we designed RT-PCR primers to amplify flanking exons, including at least one neighboring U2-type intron and one U12-type intron (see Supplemental Table 3 online). The splicing patterns of U12-type introns were examined by RT-PCR, and the identities of PCR products were confirmed by cloning and sequencing. Most U12 introns investigated in this study were completely retained in U11/U12-31K knockdown plants. By contrast, U2-type intron splicing was not affected by U11/U12-31K knockdown (Figure 4; see Supplemental Figure 3 online). The splicing of U12 introns in HIGH-LEVEL EXPRESSION OF SUGAR-INDUCIBLE GENE2 (HSI2), Quartre-Quart 1 (QQT1), Drought induced 19-1 (Di19-1), Di19-2, Di19-3, Di19-4, Di19-6, Di19-7, HISTONE DEACETYLASE2 (HDT2), HDT3, LUMINIDEPENDENS (LD), glutathione synthetase, E2FA transcription factor (E2FB), Ras family GTP binding protein, abscisic acid deficient 3 (ABA3), sodium/hydrogen exchanger 5 (NHX5), and NHX6 was affected in U11/U12-31K knockdown plants, whereas the splicing patterns of U12 introns in CAB BINDING PROTEIN 20 (CBP20), E2FA, and Di19-5 were similar in both transgenic and wild-type plants (Figure 4; see Supplemental Figure 3 online). It is noteworthy that U12 intron-containing transcripts of HSI2, QQT1, and Di19 family genes strongly accumulated in amiRNA1-4 and amiRNA1-6 alleles, indicating that the frequency of U12 intron splicing defects correlated with the severity of observed phenotypes in U11/U12-31K knockdown plants.

Figure 4.

Arabidopsis U11/U12-31K Affects U12-Dependent Intron Splicing.

The splicing patterns of several U12 intron-containing transcripts were analyzed by RT-PCR in wild-type (WT) and four different knockdown plants (amiR1-4, amiR1-6, amiR1-5, and amiR1-8). Identical results were obtained from three independent experiments, one of which is shown. The gray boxes with numbers represent exons, and the dashed and solid lines represent U12 and U2 introns, respectively.

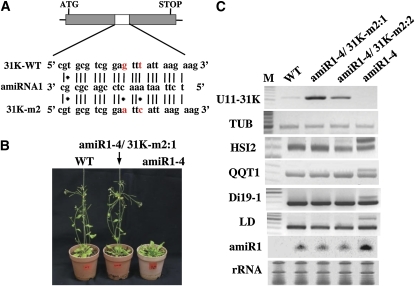

Expression of amiRNA-Resistant U11/U12-31K Recovers Normal Phenotypes

To further determine whether the developmental defects seen in U11/U12-31K knockdown plants resulted from the specific knockdown of U11/U12-31K, we generated transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing mutant U11/U12-31K, which is resistant to cleavage by amiRNA in an amiRNA1-4 background. The mutant U11/U12-31K gene (31K-m2) was designed to have G-to-A and T-to-C substitutions in the amiRNA1 target site (Figure 5A), which resulted in the disruption of U11/U12-31K cleavage by amiRNA1 and therefore formation of full-length active U11/U12-31K. As expected, transgenic plants expressing 31K-m2 in an amiRNA1-4 background showed normal phenotypes, comparable with those of wild-type plants (Figure 5B). RT-PCR analysis showed that the expression of U11/U12-31K is higher in the complementation lines than in wild-type plants (Figure 5C), confirming the successful expression of amiRNA1-resistant U11/U12-31K in the complementation plants. Furthermore, the splicing patterns of the transcripts of four representative U12 intron-containing genes, HSI2, QQT1, Di19-1, and LD, in transgenic plants expressing 31K-m2 were identical to those in wild-type plants (Figure 5C). These results further confirm that U11/U12-31K is critical for the correct splicing of U12 introns, which plays a prominent role in plant development.

Figure 5.

Recovery of Normal Phenotype and Splicing Activity in Complementation Lines.

(A) Schematic presentation and the sequences of amiRNA1 along with its wild-type target (31K-WT) and mutant target (31K-m2) designed to have C•A and A•C mismatches.

(B) The normal phenotype of amiR4-1 plants is recovered by the expression of the mutant target gene 31K-m2. WT, wild type.

(C) Expression of U11/U12-31K in complementation lines expressing the mutant target in amiR1-4 plants and normal splicing of several U12 intron-containing transcripts were analyzed by RT-PCR in the wild type and two different complementation lines (amiR1-4/31K-m2:1 and amiR1-4/31K-m2:2). The experiment was repeated three times using different batches of RNA samples, and similar results were obtained.

[See online article for color version of this figure.]

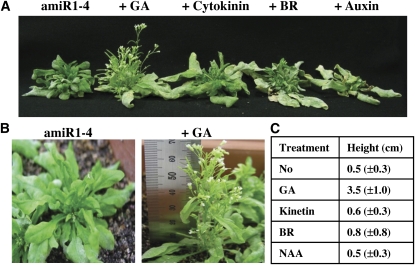

Exogenously Applied Gibberellic Acid Recovers the Stunted Stem Growth in U11/U12-31K Knockdown Plants

To gain insight into how U11/U12-31K knockdown causes stunted primary inflorescence stems, we determined the effect of exogenously applied hormones, including gibberellic acid (GA3; 100 μM), cytokinin (kinetin; 50 μM), brassinosteroid (BR; 24-epibrassinolide; 5 μM), and auxin (α-naphthalene acetic acid; 0.5 μg/mL), on the growth of U11/U12-31K knockdown plants. These hormones used are all known to influence stem growth and development. When the indicated amounts of each hormone were applied to amiRNA1-4 plants on a daily basis, we found that the stunted inflorescence stems were recovered only by the application of GA (Figure 6A). The primary inflorescence stems of amiRNA1-4 plants were~7 times longer (from 0.5 to 3.5 cm) 2 weeks after the application of GA (Figures 6B and 6C), and their length increased further upon prolonged application of GA.

Figure 6.

Effect of Exogenously Applied Hormones on the Stem Length of U11/U12-31K Knockdown Plants.

(A) Stunted inflorescence of amiR1-4 plants and phenotypes of the plants 2 weeks after application of 100 μM GA, 50 μM kinetin, 5 μM BR, or 0.5 μg/mL α-naphthalene acetic acid (NAA).

(B) Phenotypes of 6-week-old amiR1-4 plants grown in the absence (left) and presence (right) of 100 μM GA.

(C) Stem lengths of amiR1-4 plants 2 weeks after the application of each hormone.

[See online article for color version of this figure.]

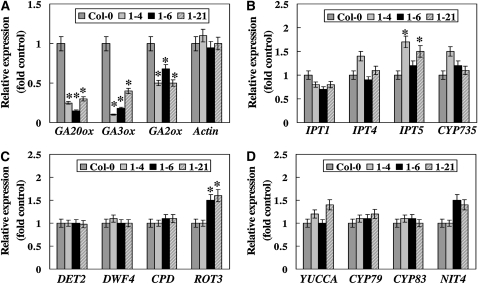

Because the inflorescence stem growth of amiRNA1-4 plants appeared to be regulated by exogenously applied GA, we next determined whether the genes involved in hormone metabolism are disturbed in U11/U12-31K knockdown plants. Several genes involved in key biosynthetic pathways for each hormone were selected for investigation: GA20-oxidase (GA20ox), GA3-oxidase (GA3ox), and GA2-oxidase (GA2ox) for GA; isopentenyl transferase (IPT1, IPT4, and IPT5) and CYP735-type p450 monooxygenase (CYP735) for cytokinin; steroid 5α-reductase (DET2), 22α-hydroxylase (DWF4), and cytochrome p450 monooxygenase (CPD and ROT3) for BR; and flavin monooxygenase-like enzyme (YUCCA), cytochrome p450 monooxygenase (CYP79 and CYP83), and nitrilase (NIT4) for auxin. The transcript levels of these genes were determined via real-time RT-PCR analysis using the primers listed in Supplemental Table 4 online. Since U11/U12-31K influences the growth of primary inflorescence stems, we specifically aimed to determine the expression levels of these genes in meristemic regions of the plants. When U11/U12-31K knockdown plants began to bolt, the leaves, roots, and stems of the plants were removed and only the meristem-containing regions were collected for RNA extraction and subsequent analysis. The means and standard errors for the transcript levels of each gene were measured from three different batches of RNA samples (Figure 7). It was evident that the transcript levels of the genes involved in GA metabolism were significantly downregulated in U11/U12-31K knockdown plants compared with the wild-type plants (Figure 7A). By contrast, transcript levels of the genes involved in cytokinin, BR, or auxin metabolism were not changed noticeably, except for ROT3 and IPT5, in U11/U12-31K knockdown plants compared with the wild-type plants (Figures 7B to 7D). It is noteworthy that the decreases in the transcript levels of GA metabolism-related genes were not apparent in the whole aerial parts of U11/U12-31K knockdown plants (see Supplemental Figure 4 online). These results demonstrate that the defect in GA biosynthesis in meristematic regions is responsible for abnormal growth and stunted inflorescence stems of U11/U12-31K knockdown plants.

Figure 7.

Expression Levels of the Genes Involved in Hormone Metabolism in U11/U12-31K Knockdown Plants.

Values are means ± sd (n = 5). Asterisks above the columns indicate values that are significantly different from control Columbia-0 values (P ≤ 0.05).

(A) Expression of GA metabolism-related genes in the meristematic region only.

(B) Expression of cytokinin metabolism-related genes in the meristematic region only.

(C) Expression of BR metabolism-related genes in meristematic region only.

(D) Expression of auxin metabolism-related genes in meristematic region only.

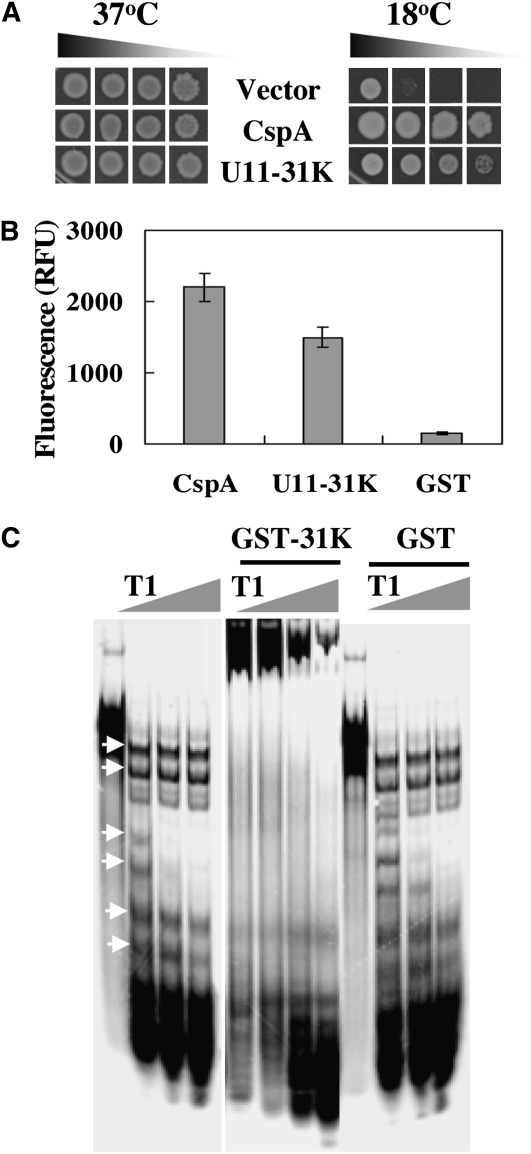

RNA Chaperone Activity of U11/U12-31K

snRNP assembly and splice site recognition require a dynamic network of snRNA–snRNA and snRNA–precursor-mRNA interactions, during which RBPs play important roles in RNA–RNA and/or RNA–protein interactions. It is likely that RBPs with RNA chaperone activity participate in this process either by assisting the folding of RNA substrates or by disrupting misfolded RNAs for the formation of splicing-competent structures. U11/U12-31K proteins contain one viral-like CCHC-type zinc finger as well as short regions rich in basic amino acids and Pro residues (Wang et al., 2007; see Supplemental Figure 1 online), the domains of which are implicated in the RNA chaperone activity of NC protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (Williams et al., 2001; Heath et al., 2003). We therefore reasoned that Arabidopsis U11/U12-31K functions as an RNA chaperone during U12 intron splicing. To determine whether U11/U12-31K harbors RNA chaperone activity, we considered the well-established complementation analysis of cold-sensitive Escherichia coli BX04 mutant cells. It has been shown that BX04 cells, which lack four cold shock protein (CSP) genes, are highly sensitive to low temperatures (Xia et al., 2001) and that CSPs function as RNA chaperones during cold adaptation (Bae et al., 2000; Phadtare et al., 2002). We therefore asked whether U11/U12-31K expression in BX04 cells can complement the cold-sensitive phenotype of BX04 cells. U11/U12-31K expression was verified in BX04 cells by immunoblot analysis (see Supplemental Figure 5A online), and BX04 cells expressing U11/U12-31K, together with positive control cells expressing E. coli CspA and negative control cells harboring the pINIII vector, were investigated for colony formation. The BX04 cells expressing each construct grew well under normal growth conditions (37°C) with no noticeable differences. However, only the BX04 cells expressing either CspA or Arabidopsis U11/U12-31K grew well when subjected to low temperature (18°C), whereas those harboring the pINIII vector did not (Figure 8A). These results show that U11/U12-31K successfully complemented the cold sensitivity of BX04 cells, which suggests that U11/U12-31K may function as an RNA chaperone similar to CspA.

Figure 8.

RNA Chaperone Activity of U11/U12-31K.

(A) The colony-forming abilities of 10−1 to 10−4 diluted BX04 E. coli cells expressing either Arabidopsis U11/U12-31K, E. coli CspA (positive control), or pINIII (negative control) were examined at normal (37°C) and cold stress (18°C) conditions.

(B) DNA melting activity of U11/U12-31K. The fluorescence of a 78-nucleotide-long molecular beacon was monitored as 10 μg of GST-31K, 5 μg of GST-CspA, or 5 μg of GST was added. Values are means ± sd (n = 5). RFU, relative fluorescence unit.

(C) The enhancement of RNase T1 cleavage of substrate RNA by U11/U12-31K was measured. The RNase T1-resistant bands, which are indicated by arrows, disappeared in the presence of the GST-31K fusion protein. The gray triangle next to T1 indicates increases in T1 concentration: 0.1, 0.2, and 0.4 μg.

To further demonstrate that U11/U12-31K possesses RNA chaperone activity, its nucleic acid melting ability was evaluated. Recombinant glutathione S-transferase (GST)-31K and GST-CspA proteins were purified from E. coli (see Supplemental Figure 5B online), and the identity of U11/U12-31K was confirmed by immunoblot analysis (see Supplemental Figure 5C online). We first determined the DNA melting ability of proteins using a molecular beacon that produces fluorescence signals upon DNA melting. Strong fluorescent signals appeared upon the addition of recombinant GST-CspA or GST-31K to the reaction mixture. However, no fluorescence was detected upon the addition of GST (Figure 8B), indicating that U11/U12-31K possesses DNA melting ability in vitro similar to CspA. We next used a ribonuclease T1 cleavage assay to determine whether U11/U12-31K is capable of melting RNA secondary structures. The RNA substrate used in this study was prepared by transcribing pET-22b(+) plasmid. The RNA substrate was shifted to upper positions only when recombinant GST-31K protein was added to the reaction mixture and not by the addition of GST (Figure 8C), indicating that U11/U12-31K binds to the RNA substrate. The addition of RNase T1 to the RNA mixture and incubation for 15 min on ice produced several RNase T1-resistant bands at lower positions (Figure 8C, indicated by arrows). However, these RNase-resistant bands disappeared when U11/U12-31K was added before RNase T1. By contrast, cleavage of RNA substrates by RNase T1 was not increased by the addition of GST. These results indicate that U11/U12-31K destabilizes RNA secondary structure, allowing RNase T1 to further digest RNAs into smaller fragments. All of these results demonstrate that U11/U12-31K is capable of melting nucleic acids and harbors RNA chaperone activity.

DISCUSSION

The results of our study indicate that U11/U12-31K, the minor spliceosomal protein, is crucial for plant development, particularly in the reproductive stages, such as embryonic development and inflorescence stem elongation. The severity of phenotypes exhibited by U11/U12-31K knockdown plants appears to correlate with the degree to which U12-dependent splicing is defective. The observation that insertion of homozygous T-DNA in the U11/U12-31K locus causes embryonic lethality (Figure 1A) implies that U11/U12-31K plays an essential role in plant development, which is consistent with previous reports that the minor spliceosomal components are essential for cell viability and proliferation in other organisms (Otake et al., 2002; Will et al., 2004; König et al., 2007). The serrated leaf phenotype observed in amiRNA1-4 and amiR1-6 plants resembles that of other well-characterized mutants, including ABA hypersensitive 1 (abh1/cbp80), cbp20, and SERRATE (se-1), all of which demonstrate impaired RNA metabolism and altered leaf morphology, flowering time, and ABA response (Hugouvieux et al., 2001; Bezerra et al., 2004; Papp et al., 2004; Grigg et al., 2005; Lobbes et al., 2006; Laubinger et al., 2008). However, mutation of U11/U12-31K produced pleiotropic effects, such as serrated leaf formation and arrested meristem growth, without altering ABA response and flowering time. This observed phenotype is likely a specific effect of U11/U12-31K knockdown and not a general effect of RNA metabolism impairment.

It was well supported that U11/U12-31K acts after bolting rather than at the vegetative stage. Although expression of U11/U12-31K was lower in seedlings than in adult plants (Figure 1B), U12-dependent splicing was found to be normal at the seedling stage of wild-type plants and defective at the seedling stage of U11/U12-31K knockdown plants. This suggests that the endogenous low level of U11/U12-31K expression allows U12 intron splicing. Despite aberrant U12-dependent splicing at the seedling stage, the morphology of knockdown plants was similar to that of wild-type plants at this growth stage (Figure 3A). In correlation with the observed phenotypic defects in knockdown plants, we found higher expression of U11/U12-31K in the shoot apical meristem, late stage seeds, and pollen, further suggesting important roles for U11/U12-31K in these tissues. The defects in inflorescence stem growth in homozygous amiR1-4 and amiR1-21 plants were more severe than those in heterozygous plants (Figure 2A), and the significant difference in stem growth between wild-type and U11/U12-31K knockdown plants cannot be explained by the difference in epidermal cell size in the primary inflorescence stem. This suggests that U11/U12-31K is mainly responsible for meristem activity.

Among organisms possessing a minor spliceosome, U12 introns are often found in genes that function in important information processes, such as DNA replication/repair, RNA processing, and translation, which suggests a role for U12 introns in the regulation of cell proliferation (Burge et al., 1998; Chang et al., 2007). It remains unknown at present if the observed phenotypic defects in the U11/U12-31K knockdown plants are caused by the abortion of all U12-dependent splicing. However, it is clear that a set of U12 intron-containing genes could be responsible for the developmental defects. Our analysis of U12-dependent splicing showed that the mature mRNA levels of QQT1, HSI2, and several Di19 genes were significantly reduced particularly in amiR1-4 and amiR1-6 knockdown plants, which displayed much more severe phenotypic defects compared with other knockdown plants (Figure 4; see Supplemental Figure 3 online). QQT1 encodes an ATP/GTP binding protein that colocalizes with microtubules during cell division. Moreover, insertion of T-DNA in the second intron of QQT1 made the allele embryo defective (Lahmy et al., 2007). HSI2 is a B3 DNA binding transcription factor that is known to repress the sugar-inducible ectopic expression of seed maturation genes during seedling growth (Tsukagoshi et al., 2007). The Arabidopsis Di19 gene family has been implicated in stress and light signaling pathways (Milla et al., 2006). We propose that cumulative defects in the splicing of these U12 introns are responsible for the abnormal developmental phenotypes observed in U11/U12-31K knockdown plants.

It is conceivable that the stunted primary inflorescence stems observed in U11/U12-31K knockdown plants may be due to the defect in hormone metabolism necessary for stem growth in meristemic regions. It is noteworthy that exogenous application of cytokinin, BR, or auxin did not recover the stunted inflorescence stem growth, whereas application of GA increased the inflorescence stem growth (Figure 6). GA promotes stem growth by stimulating both cell division and cell expansion (Jacobs, 1997). Since U11/U12-31K knockdown plants express a significantly lower level of GA biosynthesis-related genes than wild-type plants (Figure 7), it is evident that the defect in GA biosynthesis is a key reason for the stunted primary inflorescence stems in U11/U12-31K knockdown plants. Since the splicing of most U12 introns is affected by U11/U12-31K knockdown, it is unclear at present how U12 intron splicing influences the expression of GA metabolism-related genes. It would be of keen interest to identify possible factors or components that connect U12 intron splicing with GA metabolism in plants.

Although the molecular mechanism by which U11/U12-31K facilitates U12-type intron splicing is not clear, U11/U12-31K most likely functions as an RNA chaperone during U12 intron splicing based on analyses that demonstrate RNA chaperone activity, such as BX04 complementation, RNase T1 cleavage, and DNA melting (Figure 8). A major effect of the RNA chaperone activity of U11/U12-31K could be the maintenance of pre-RNA substrates in splicing-competent conformations. It is also likely that U11/U12-31K facilitates the rearrangement of spliceosomal RNAs and/or mRNAs during the splicing process. The observation that U11/U12-31K influences the splicing of diverse classes of U12 introns further supports the hypothesis that U11/U12-31K functions as an RNA chaperone, since RNA chaperones bind their RNA substrate sequences nonspecifically (Jiang et al., 1997; Kim et al., 2007). However, it should be emphasized that splicing of some U12 introns, including CBP20, E2FA, E2FB, and Di19-5, was unaffected by U11/U12-31K knockdown (Figure 4; see Supplemental Figure 3 online). It is likely that these U12 introns can fold into splicing-competent structures without the RNA chaperone activity of U11/U12-31K. However, it remains uncertain whether U11/U12-31K exerts its role by directly binding to RNA substrates or if additional protein factors are required. Although there is no direct evidence confirming the presence of Arabidopsis U11/U12-31K in minor spliceosomal complexes, the existence of human U11/U12-31K in 18S U11/U12 snRNPs (Will et al., 2004) suggests that Arabidopsis U11/U12-31K may well be present in minor spliceosomal complexes. In addition, the presence of an RNA recognition motif and CCHC-type zinc knuckle domain in Arabidopsis U11/U12-31K suggests that this protein comes into contact with U11 or U12 snRNA. Considering these results, we propose that U11/U12-31K is involved in U12 intron splicing as a component of the minor spliceosomal complex.

In conclusion, these findings demonstrate that U11/U12-31K, an Arabidopsis U12-type spliceosomal protein homologous to a human U11/U12 snRNP-associated protein, plays crucial roles in plant growth and development. Considering that the biological functions of most U11/U12-31K proteins are not yet determined in either plants or animals, our proposal that Arabidopsis U11/U12-31K is an indispensible RNA chapereone that functions in U12 intron splicing and is necessary for the normal growth and development of plants opens new opportunities for the further investigation of the roles of U11/U12-31K proteins. It is important to analyze the splicing patterns of other U12-type introns in wild-type and U11/U12-31K knockdown plants and also to determine whether U11/U12-31K interacts with these U12 intron-containing genes in plants.

METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana Columbia-0 ecotype was grown at 23°C under long-day conditions (16-h-light/8-h-dark cycle). Plants were also grown in half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium containing 1% sucrose. Arabidopsis seeds with T-DNA inserted into U11/U12-31K (WiscDsLox485-488L9) were obtained from the ABRC.

amiRNA Construction

Web MicroRNA Designer (http://wmd3.weigelworld.org/) was used to construct amiRNA for the specific downregulation of U11/U12-31K expression. Three different amiRNAs were generated using the primer pairs listed in Supplemental Table 1 online to target different sites of the U11/U12-31K transcript listed in Supplemental Table 2 online. Transformation of Arabidopsis was performed by vacuum infiltration (Bechtold and Pelletier, 1998) using Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101. The T3 or T4 homozygous lines were selected and used for investigation of phenotypes.

RT-PCR and RNA Gel Blot Analysis

For RT-PCR analysis of U12 intron-containing genes, total RNAs were extracted from 30-d-old plants, and 5 to 10 μg of total RNAs were treated with RQ1 DNase (Promega) and further purified using an RNeasy cleanup kit (Qiagen). To determine the expression patterns of U11/U12-31K in different organs, total RNAs were extracted from 6-d-old seedlings and from different organs of 35-d-old plants. Two hundred nanograms of RNAs were reverse transcribed and amplified using a one-step RT-PCR kit (Qiagen) and the primers listed in Supplemental Table 3 online. The quantification of RNA transcripts was conducted in a Rotor-Gene real-time thermal cycling system (Corbett Research) using the primers listed in Supplemental Table 3 online. For the detection of 21-mer mature amiRNAs, 12 μg of total RNA was separated via denaturing 12% PAGE and transferred to a nylon membrane by a semidry blotting device (TransBlot SD; Bio-Rad). RNA gel blots were hybridized in 1× Ultrahyb-Oligo hybridization buffer (Ambion) with a radiolabeled probe complementary to amiRNA1. After washing the membrane with washing buffer (2× SSC, 0.25% SDS), the signals for amiRNA were detected using a phosphor imager (Fuji).

Ribonuclease Cleavage Assay

The 32P-labeled RNA substrates were prepared by transcription of pET-22b(+) plasmid using T7 RNA polymerse (Promega), followed by incubation with recombinant GST-31K fusion proteins for 15 min on ice. The reaction products were separated on an 8% acrylamide gel. All experimental conditions were maintained essentially as described (Kim et al., 2007).

Cold Shock Assay in E. coli

U11/U12-31K cDNA was cloned into the pINIII vector (Masui et al., 1983), and the cold shock test in E. coli was conducted essentially as described (Kim et al., 2007). The pINIII expression vector was transformed into E. coli BX04 mutant cells (Xia et al., 2001), and the cells were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium to an optical density of 1.0 at 600 nm. Cell cultures were subjected to serial dilution, spotted on Luria-Bertani-agar plates, and incubated at low temperature (18°C). For detection of U11/U12-31K in E. coli BX04 cells, soluble proteins from bacterial extracts were separated by SDS-12% PAGE, and then transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The signals for U11/U12-31K were detected using anti-His HRP conjugate antibody (Novagen) and a chemiluminescence image analyzer (Fuji).

Nucleic Acid Melting Assay

The molecular beacon used in this study was a 78-nucleotide-long hairpin-shaped DNA molecule labeled with a fluorophore (tetramethyl rhodamine) and quencher (dabcyl) (Phadtare et al., 2002). The nucleic acid melting assay was conducted essentially as described (Kim et al., 2007). Briefly, recombinant GST-31K fusion proteins were reacted with the molecular beacon, and emitted fluorescence was measured using a Spectra Max GeminiXS spectrofluorometer (Molecular Devices) with excitation and emission wavelengths of 555 and 575 nm, respectively.

Analysis of Cellular Localization of U11/U12-31K

cDNA corresponding to U11/U12-31K was fused in frame with GFP, and the 31K-GFP fusion protein was expressed in Arabidopsis under control of the cassava mosaic virus promoter. The cellular expression of 31K-GFP was observed in root and leaf samples using a Zeiss LSM510 laser scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss) equipped with an inverted Zeiss Axiovert 100M microscope. Excitation and emission wavelengths were 488 and 505 to 545 nm, respectively.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers At3g10400 (At U11-31K), CAO68868 (Vv 31K), ACG44013 (Zm 31K), EDQ74690 (Pp 31K), gi_21314767 (Hs 31K), and Os09g0549500 (Os 31K). The Arabidopsis T-DNA insertion mutant is WiscDsLox485-488L9.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure 1. Alignment of Amino Acid Sequences of 31K Proteins from Different Organisms.

Supplemental Figure 2. Growth and Developmental Defect Phenotypes of Artificial miRNA-Mediated Knockdown Mutants.

Supplemental Figure 3. Abnormal Splicing Patterns of U12-Type Introns in Artificial miRNA-Mediated Knockdown Mutants.

Supplemental Figure 4. Expression Levels of GA Metabolism-Related Genes in the Whole Aerial Part of U11/U12-31K Knockdown Plants.

Supplemental Figure 5. Expression of U11/U12-31K in BX04 E. coli Mutant Cells and Purification of GST-31K Fusion Proteins.

Supplemental Table 1. PCR Primers Used for Artificial MicroRNA Construction.

Supplemental Table 2. Target Site Prediction for Artificial MicroRNA.

Supplemental Table 3. Gene-Specific Primer Pairs Used in RT-PCR Experiments.

Supplemental Table 4. Gene-Specific Primer Pairs Used in Real-Time RT-PCR Experiments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Inouye and S. Phadtare for the BX04 mutant cells and pINIII vector and Detlef Weigel for the pRS300 vector. We thank the ABRC for providing Arabidopsis T-DNA insertion mutants. This work was supported in part by a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea to the Agricultural Plant Stress Research Center (R11-2001-092-04002-0) of Chonnam National University and by a grant (CG2112-1) from the Crop Functional Genomics Center of the 21st Century Frontier Research Program funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology and Rural Development Administration of Republic of Korea.

References

- Alioto T.S. (2007). U12DB: A database of orthologous U12-type spliceosomal introns. Nucleic Acids Res. 35(Database issue): D110–D115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae W., Xia B., Inouye M., Severinov K. (2000). Escherichia coli CspA-family RNA chaperones are transcription antiterminators. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97: 7784–7789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechtold N., Pelletier G. (1998). In planta Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of adult Arabidopsis thaliana plants by vacuum infiltration. Methods Mol. Biol. 82: 259–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benecke H., Lührmann R., Will C.L. (2005). The U11/U12 snRNP 65K protein acts as a molecular bridge, binding the U12 snRNA and U11-59K protein. EMBO J. 24: 3057–3069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezerra I.C., Michaels S.D., Schomburg F.M., Amasino R.M. (2004). Lesions in the mRNA cap-binding gene ABA HYPERSENSITIVE 1 suppress FRIGIDA-mediated delayed flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 40: 112–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckman J.S., Bosche W.J., Gorelick R.J. (2003). Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid zn(2+) fingers are required for efficient reverse transcription, initial integration processes, and protection of newly synthesized viral DNA. J. Virol. 77: 1469–1480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge C.B., Padgett R.A., Sharp P.A. (1998). Evolutionary fates and origins of U12-type introns. Mol. Cell 2: 773–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang W.-C., Chen Y.-C., Lee K.-M., Tarn W.-Y. (2007). Alternative splicing and bioinformatic analysis of human U12-type introns. Nucleic Acids Res. 35: 1833–1841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frilander M.J., Steitz J.A. (1999). Initial recognition of U12-dependent introns requires both U11/5′ splice-site and U12/branchpoint interactions. Genes Dev. 13: 851–863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigg S.P., Canales C., Hay A., Tsiantis M. (2005). SERRATE coordinates shoot meristem function and leaf axial patterning in Arabidopsis. Nature 437: 1022–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath M.J., Derebail S.S., Gorelick R.J., DeStefano J.J. (2003). Differing roles of the N- and C-terminal zinc fingers in human immunodeficiency virus nucleocapsid protein-enhanced nucleic acid annealing. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 30755–30763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose T., Shu M.-D., Steitz J.A. (2004). Splicing of U12-type introns deposits an exon junction complex competent to induce nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 17976–17981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugouvieux V., Kwak J.M., Schroeder J.I. (2001). An mRNA cap binding protein, ABH1, modulates early abscisic acid signal transduction in Arabidopsis. Cell 106: 477–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs T. (1997). Why do plant cells divide? Plant Cell 9: 1021–1029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W., Hou Y., Inouye M. (1997). CspA, the major cold-shock protein of Escherichia coli, is an RNA chaperone. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 196–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.S., Park S.J., Kwak K.J., Kim Y.-O., Kim J.Y., Song J., Jang B., Jung C.-H., Kang H. (2007). Cold shock domain proteins and glycine-rich RNA-binding proteins from Arabidopsis thaliana can promote the cold adaptation process in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 35: 506–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- König H., Matter N., Bader R., Thiele W., Müller F. (2007). Splicing segregation: The minor spliceosome acts outside the nucleus and controls cell proliferation. Cell 131: 718–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahmy S., Guilleminot J., Schmit A.C., Pelletier G., Chaboute M.E., Devic M. (2007). QQT proteins colocalize with microtubules and are essential for early embryo development in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 50: 615–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laubinger S., Sachsenberg T., Zeller G., Busch W., Lohmann J.U., Rätsch G., Weigel D. (2008). Dual roles of the nuclear cap-binding complex and SERRATE in pre-mRNA splicing and microRNA processing in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105: 8795–8800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine A., Durbin R. (2001). A computational scan for U12-dependent introns in the human genome sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 29: 4006–4013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobbes D., Rallapalli G., Schmidt D.D., Martin C., Clarke J. (2006). SERRATE: A new player on the plant microRNA scene. EMBO Rep. 7: 1052–1058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorković Z.J., Lehner R., Forstner C., Barta A. (2005). Evolutionary conservation of minor U12-type spliceosome between plants and humans. RNA 11: 1095–1107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorković Z.J., Lopato S., Pexa M., Lehner R., Barta A. (2004). Interactions of Arabidopsis RS domain containing cyclophilins with SR proteins and U1 and U11 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein-specific proteins suggest their involvement in pre-mRNA splicing. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 33890–33898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masui Y., Coleman J., Inouye M. (1983). Multipurpose expression cloning vehicles in Escherichia coli. In Experimental Manipulation of Gene Expression. Inouye M., (New York: Academic Press; ), pp. 15–32 [Google Scholar]

- Milla M.A.R., Townsend J., Chang I.F., Cushman J.C. (2006). The Arabidopsis AtDi19 gene family encodes a novel type of Cys2/His2 zinc-finger protein implicated in ABA-independent dehydration, high-salinity stress and light signaling pathways. Plant Mol. Biol. 61: 13–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaminami K., Karlson D.T., Imai R. (2006). Functional conservation of cold shock domains in bacteria and higher plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103: 10122–10127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otake L.R., Scamborova P., Hashimoto C., Steitz J.A. (2002). The divergent U12-type spliceosome is required for pre-mRNA splicing and is essential for development in Drosophila. Mol. Cell 9: 439–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp I., Mur L.A., Dalmadi A., Dulai S., Koncz C. (2004). A mutation in the Cap Binding Protein 20 gene confers drought tolerance to Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 55: 679–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.J., Kwak K.J., Oh T.R., Kim Y.O., Kang H. (2009). Cold shock domain proteins affect seed germination and growth of Arabidopsis thaliana under abiotic stress conditions. Plant Cell Physiol. 50: 869–878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessa H.K., Will C.L., Meng X., Schneider C., Watkins N.J., Perälä N., Nymark M., Turunen J.J., Lührmann R., Frilander M.J. (2008). Minor spliceosome components are predominantly localized in the nucleus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105: 8655–8660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phadtare S., Inouye M., Severinov K. (2002). The nucleic acid melting activity of Escherichia coli CspE is critical for transcription antitermination and cold acclimation of cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 7239–7245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkowitsch L., Chen D., Stampfl S., Semrad K., Waldsich C., Mayer O., Jantsch M.F., Konrat R., Bläsi U., Schroeder R. (2007). RNA chaperones, RNA annealers and RNA helicases. RNA Biol. 4: 118–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell A.G., Charette J.M., Spencer D.F., Gray M.W. (2006). An early evolutionary origin for the minor spliceosome. Nature 443: 863–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C., Will C.L., Makarova O.V., Makarov E.M., Lührmann R. (2002). Human U4/U6.U5 and U4atac/U6atac.U5 tri-snRNPs exhibit similar protein compositions. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 3219–3229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab R., Ossowski S., Riester M., Warthmann N., Weigel D. (2006). Highly specific gene silencing by artificial microRNAs in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18: 1121–1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheth N., Roca X., Hastings M.L., Roeder T., Krainer A.R., Sachidanandam R. (2006). Comprehensive splice-site analysis using comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 34: 3955–3967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley J.P., Guthrie C. (1998). Mechanical devices of the spliceosome: Motors, clocks, springs, and things. Cell 92: 315–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley J.P., Guthrie C. (1999). An RNA switch at the 5′ splice site requires ATP and the DEAD box protein Prp28p. Mol. Cell 3: 55–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukagoshi H., Morikami A., Nakamura K. (2007). Two B3 domain transcriptional repressors prevent sugar-inducible expression of seed maturation genes in Arabidopsis seedlings. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 2543–2547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turunen J.J., Will C.L., Grote M., Lührmann R., Frilander M.J. (2008). The U11-48K protein contacts the 5′ splice site of U12-type introns and the U11-59K protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28: 3548–3560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Gao M.X., Li L., Wang B., Hori N., Sato K. (2007). Isolation, expression, and characterization of the human ZCRB1 gene mapped to 12q12. Genomics 89: 59–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassarman K.M., Steitz J.A. (1992). The low-abundance U11 and U12 small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs) interact to form a two-snRNP complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12: 1276–1285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Will C.L., Schneider C., Hossbach M., Urlaub H., Rauhut R., Elbashir S., Tuschl T., Lührmann R. (2004). The human 18S U11/U12 snRNP contains a set of novel proteins not found in the U2-dependent spliceosome. RNA 10: 929–941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams M.C., Rouzina I., Wenner J.R., Gorelick R.J., Musier-Forsyth K., Bloomfield V.A. (2001). Mechanism for nucleic acid chaperone activity of HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein revealed by single molecule stretching. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98: 6121–6126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H.J., Gaubier-Comella P., Delseny M., Grellet F., Van Montagu M., Rouzé R. (1996). Non-canonical introns are at least 10(9) years old. Nat. Genet. 14: 383–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia B., Ke H., Inouye M. (2001). Acquirement of cold sensitivity by quadruple deletion of the cspA family and its suppression by PNPase S1 domain in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 40: 179–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W., Brendel V. (2003). Identification, characterization and molecular phylogeny of U12-dependent introns in the Arabidopsis thaliana genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 31: 4561–4572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.