Abstract

The mental health consequences of living with intimate partner violence (IPV) are substantial. Despite the growing awareness of the incidence of depression and PTSD in women experiencing IPV, few studies have examined prospectively the experience of IPV during pregnancy and the impact of the abuse on women’s mental health. As a component of a larger clinical trial of an intervention for pregnant abused women, 27 women participated in a qualitative study of their responses to the abuse in the context of pregnancy and parenting. Results indicate that women’s changing perceptions of self was related to mental distress, mental health, or both mental distress and mental health.

Over the last decade violence against women has received increased attention among researchers and practitioners. Violence against women is now seen as a complex health problem and not just a criminal or social problem. Recent population based surveys have found a 33–37% lifetime prevalence and a 3–12% annual prevalence of intimate partner violence (IPV). More than 7% of women have been sexually assaulted by an intimate partner in their lifetime and 0.2% have been assaulted in the last year. Rates on non-lethal IPV are highest among women aged 16–24 and women residing in low income households. Among African American women between the ages of 15–24 years, IPV is the leading cause of premature death and injury from non-lethal causes.

In numerous research overviews, such as Campbell, Garcia-Moreno, and Sharps (2004), as well as a meta-analyses (Murphy, Shei, Myhr, & DuMont, 2001), abuse during pregnancy is recognized as a risk to the health of a woman (depression, smoking), her fetus, and neonate (e.g., low birth weight, child abuse). As many as 3% to 19% of pregnant women are abused; the most common prevalence reported is between 3.9% and 8.3% across studies in North America (Gazmararian et al., 1996).

These data underscore the importance of health professionals’ assessment of all pregnant women for IPV. More than 95% of pregnant women receive prenatal care, and often abused women do not seek medical care except during pregnancy (Rodriguez, Bauer, McLoughlin, & Grumback, 1999). Early recognition and subsequent care of those affected by IPV can facilitate more positive short- and long-term health outcomes. Despite the importance of the IPV-maternal health relationship, few studies have addressed the abused women’s mental health concerns. The purpose of this study was to elicit women’s perceptions of the experience of IPV during pregnancy and after birth and to examine the impact of the abuse on their mental health.

BACKGROUND

IPV During Pregnancy: Maternal Mental Health Correlates

Previous research has suggested that the mental health consequences associated with IPV may affect the parenting abilities of female survivors of IPV. There is evidence that maternal stress, in general, results in deleterious mental and physical health effects and developmental outcomes for infants and children. Abused mothers are very concerned with the well-being of their children, but they often report that daily survival needs are so overwhelming that the needs of their children, including emotional needs, are often overlooked or unmet.

The mental health consequences of living in an abusive relationship are also substantial, in part due to the repeated exposure to trauma that many women experience. Nearly 66% of the women surveyed for the National Violence Against Women Survey (NVAW) study reported two or more incidences of physical violence by the same partner, with an average of seven. Over two-thirds were victimized by the same partner for more than a year (mean: 4.5 years) (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000).

The myriad of mental health sequelae among abused women include depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), phobias, anxiety, panic disorders, and substance abuse disorders (Carbone-Lopez, Kruttschnitt, & Macmillan, 2006; Pico-Alfonso et al., 2006). A comprehensive meta-analysis by Golding (1999) showed that abused women were three to five times more likely to experience depression, suicidality, PTSD, alcohol abuse, and drug abuse than the general population. Results from the NVAW study support the links between IPV and depression, heavy alcohol use, and drug use (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000). While this study did not measure suicidality or PTSD, smaller studies have shown positive correlations between abuse and depression, PTSD, and suicidality in women (Houry, Kemball, Rhodes, & Kaslow, 2006; Nixon, Resick, & Nishith, 2004). In a recent population based survey, women who experienced psychological abuse during pregnancy, were more likely to experience postnatal depression (Tiwari et al., 2008).

Depression and PTSD are complex health issues with many mediating influences. Depression in abused women has been associated with daily stressors, childhood abuse, forced sex in the relationship, marital separations, change in residence, increased number of children, and child behavior problems (Campbell & Lewandowski, 1997; Cascardi, O’Leary, & Schlee, 1999). Factors influencing PTSD in abused women include dominant partners, social isolation, severity and number of violent episodes, presence of forced sex, a past history of child sexual abuse, trauma-related guilt and avoidant coping strategies (Astin, Lawrence & Foy, 1993; Astin, Ogland-Hand, Coleman, & Foy, 1995; Street, Gibson, & Holohan, 2005; Vitanza, Vogel, & Marshall, 1995). Over time, an abused woman’s level of depression lessens with lessened IPV, but PTSD persists long after the abuse has stopped. Woods (2000) found that 66% of the abused women continued to have PTSD symptoms despite being out of the abusive relationship for an average of 9 years (range 2–23 years).

Abused women experience depression and PTSD as comorbidities at a much higher rate than non-abused women. Two studies specifically examining the comorbidity of major depressive disorder and PTSD in abused women found that in 49–75% of the cases, major depression occurred in the context of PTSD (Nixon et al., 2004; Stein & Kennedy, 2001). Similarly, Levendosky and colleagues (2006) found that more IPV was related to worse mental health, including depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem. These researchers also found in their prospective study of adolescent mothers that the cumulative effect of IPV is to increase the level of depressive symptoms. In spite of the evidence of the associations of PTSD and IPV, there have been no identified published studies of PTSD in battered pregnant women and few longitudinal studies of PTSD in abused women to assess patterns over time. Silva and colleagues (1997) found that the severity of symptoms of both intrusion and avoidance PTSD symptoms were significantly correlated with severity of IPV regardless of ethnicity of the pregnant women.

Domestic Violence Enhanced Home Visitation (DOVE) Study

Purpose

The overall purpose of the DOVE randomized control trial was to test the effectiveness and efficacy of a structured IPV intervention for abused mothers and their infants/toddlers in a proposed sample of 360 mothers and infants, using three settings (two urban and one rural). Qualitative methods were embedded in the trial in a triangulated approach. This paper reports the results of baseline data on a subsample of 27 women who participated in qualitative interviews at Time One. The purposes of those interviews were: (1) to enhance understanding of the impact of setting (urban vs. rural) on women’s experiences with support seeking and coping with IPV; and (2) to understand the responses of the women to the IPV in the context of the pregnancy.

Procedures

Women were recruited for the study from health departments in three settings, one rural and two urban. All women referred to a community prenatal home visiting (HV) program are screened briefly for abuse by the HV nurse using the Abuse Assessment Screen and the Women’s Experience with Battering Scale (Smith, Earp, & Devellis, 1995; Soeken, McFarlane, Parker, & Lominak, 1998). If the woman screened positive for current abuse or in the year prior to pregnancy, a nurse from the research team contacted the woman to arrange to review the informed consent. If the woman agreed to participate in the study, then the following instruments were used to collected data at baseline. IPV frequency and severity were measured by Danger Assessment Scale (Campbell, Sharps, & Glass, 2000) and the Conflicts Tactics Scale (Straus, Hamby, & Sugarman, 1996). Maternal physical health and mental health (stress, depression, self-esteem, PTSD) were measured using the Parenting Stress Index (Abidin, 1995), the Prenatal Psychosocial Profile (Bullock, 1996), the Edinburgh Depression Scale (Cox, Chapman, Murray, & Jones, 1996), and the Davidson Trauma Scale (Davidson et al., 2003). Only the results of the instruments related to IPV and maternal mental health are reported here. For the depression measure (Edinburgh Depression Scale; Cox et al., 1996), scores greater than 12 are indicative of depression and for the Davidson Trauma Scale (Davidson et al., 2003) scores of 40 or more indicate PTSD.

QUALITATIVE METHODS

Purpose

The qualitative arm of the study was designed to strengthen the interpretation of the women’s responses to the IPV and, therefore, also their responses to the DOVE intervention. The goal of the qualitative portion of the study was to learn more from the participants about the patterns of IPV, what they thought influenced these patterns, and their evaluation of resources in their residential setting. Qualitative interviews were conducted by research nurses, doctoral students, and co-investigators on the study. All interviewers received training prior to conducting the interviews. The training consisted of a day-long workshop on qualitative methods and qualitative research interviewing techniques (conducted by the first author).

Sample

A subsample of women who consented to the quantitative study were invited to participate in the qualitative study. Women were selected for the qualitative portion of the study using purposive sampling of characteristics identified in the literature as related to IPV experience or alternative characteristics that were previously understudied but had theoretical importance to the intervention.

Qualitative Interviews

Interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide based on the specific aims of the study and the review of the literature on IPV and pregnancy. Whereas the interview followed a topical outline, and therefore all women were asked the same broad questions, not all interviews provided the same structured responses or even emphasized the same topics. Baseline interviews lasted approximately 60–90 minutes and were conducted in the women’s homes.

A guiding principle of the interviews was that it was important to allow the women to tell their story because IPV is a highly personal and emotionally charged experience. Building rapport with the women was important, and they were encouraged to describe the overall context of the abuse. A major goal of the initial interview was to elicit the women’s perceptions of the impact of IPV on them personally, the impact on their children and/or unborn child, what it was like to tell their families, and their experiences with seeking help and support from family members or resources in the community.

Qualitative Analysis

All interviews were transcribed verbatim and transcripts were reviewed for accuracy by the interviewer. Interviews were coded as they were completed by research team members trained in the coding process. Two members of the research team were primarily responsible for the coding activities, following a day-long training session on qualitative data analysis. This training included a opportunity for group coding of several transcripts in order to achieve consistency in scope of coding (larger “chunks” versus line by line coding), as well as clarification of the purposes and perspective of the analysis. Thus the coding process initially was “open,” that is, the codes or labels assigned to the text used the words of the women themselves, such as “fussing.” Some codes were determined a priori, for example, the codes related to social support and influence of setting. Other codes, including the major categories of codes presented here, were identified inductively from the open coding process. These in vivo codes were discussed at length by the members of the analysis team. Definitions were developed and discussions continued until all team members reached consensus on the use of the codes and their definitions. The goal of the analysis was to identify processes women engaged to deal with the abuse, and the contextual and conditional factors that influenced their responses to the situations. In this way, the impact of the DOVE intervention, if any, could be contextualized and understood at a micro level.

RESULTS

Description of the Participants

The demographic characteristics of the larger sample and the subsample of 27 women who participated in the qualitative interview at baseline are shown in Table 1. Overall, the women who participated in the qualitative interviews did not differ on most characteristics from the women in the larger sample with a few exceptions. A greater percentage of the interview participants were European Americans, and were more educated. In both groups, the women were largely unemployed and single at the time of the study. Participants in the sub-sample ranged in age from 14 to 32 years of age, with a mean age of 23.9 years. There were nearly equal numbers of African Americans and Caucasians. Most women (n = 18) were high school graduates or had a GED. When asked about their health before the pregnancy, most women (n = 23) rated their physical health as “good” or “excellent.” However, only 9 of the 27 participants rated their mental health as “good” or “excellent.” Only two of the women indicated that the pregnancy was planned, with seven women indicating that the pregnancy was a result of forced sex or not being allowed to use birth control. At the time of the baseline interviews, 63% (n = 17) indicated that the pregnancy is now wanted, with the remaining ten women indicating they are ambivalent about the pregnancy.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics at Baseline (%)

| Demographic | Total sample (n = 80) % | Subsample (n = 27) % |

|---|---|---|

| Race | ||

| African American | 51 | 44 |

| European American | 38 | 48 |

| Latina | 5 | 0 |

| Other | 6 | 8 |

| Education* | ||

| Less than H.S. | 35 | 22 |

| H.S./GED | 26 | 22 |

| Some college/trade | 20 | 26 |

| College/trade grad | 18 | 19 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 53 | 52 |

| Partnered/not married | 16 | 7 |

| Married | 13 | 15 |

| Divorced | 6 | 11 |

| Other | 13 | 11 |

| Employment Status** | ||

| Employed full-time | 18 | 15 |

| Employed part-time | 18 | 15 |

| Student | 15 | 14 |

| Unemployed | 64 | 70 |

Totals do not add up to 100 due to missing responses.

Totals add up to >100 due to multiple responses (“student” and “employed”)

Results of Quantitative Measures of Mental Health

Table 2 illustrates the scores on these measures for the total sample of 80 and the subsample of 27 who participated in the qualitative interviews at baseline. At baseline, based on the frequency distribution of scores, almost half (48%) were classified as depressed, and slightly more than half (52%) were classified as suffering from PTSD.

TABLE 2.

IPV and Mental Health Indicators at Baseline

| Health Indicator | Total Sample (n = 80) means | Subsample (n = 27) means |

|---|---|---|

| Conflict Tactics Scale (IPV) | 98 | 82 |

| Edinburgh Depression Scale (depression) | 14 | 14 |

| Davidson Trauma Scale (PTSD) | 44 | 49 |

| Severity of Violence Against Women Scale | 100 | 93 |

| Women’s Experiences with Battering | 45 | 41 |

Results of the Qualitative Analysis

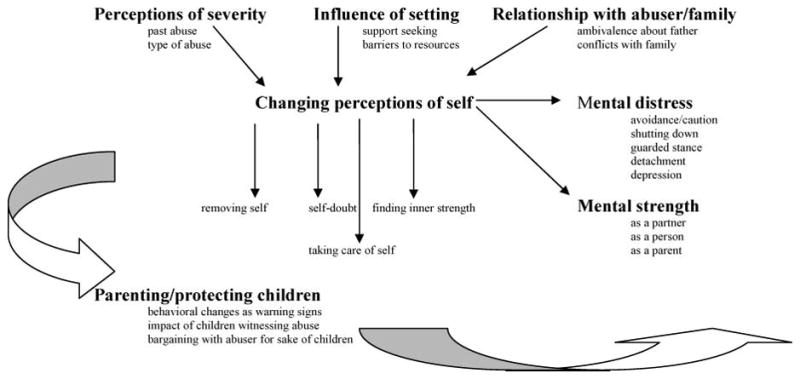

Two major categories emerged from the data analysis: women’s “changing perceptions of self,” and “parenting/protecting children.” These two categories emerged as central to the understanding of women’s responses to IPV during pregnancy and thus provided an organizing framework for other related codes. The proposed relationship of these categories and the conditional and contextual factors influencing them are shown in Figure 1.

FIG. 1.

Women’s responses to IPV during pregnancy: Mental health impact.

Changing Perceptions of Self

One of the codes we examined in the qualitative data to learn more about the impact of IPV during pregnancy on the women’s mental health was “changing perceptions of self.” This code emerged from the inductive phase of the data analysis. In other words, the women responded to broad questions about the abuse experience, the context of the abuse, and their response to the abuse. In examining these data related to women’s descriptions of how they saw themselves and how they evaluated their responses to the abuse, it became clear that this code was a broader category that encompassed mental health issues. Since we had quantitative data for depression and PTSD, we then examined the data for exemplars of those aspects of mental health. We were not bound by those quantitative definitions however, but continued to examine the data holistically, in a “back and forth” process of particulars (transcript excerpts) and the transcripts as a whole. In this way, we could examine the code “changing description of self,” to include descriptions of the participant’s perception of self as a person, including values, belief system, and any positive or negative descriptors of self. The code also included any evaluative statements about her role as a parent. Subthemes here were decisions about her leaving the situation and feeling strong in the decision. These themes in particular seemed to signify mental strength.

Two subthemes that reflected the women’s sense of self were: “taking care of self” and “self-doubt.” From these themes we see that women were actively engaged in an ongoing assessment of self and what could be done on a personal level. The phrase that one woman used, “I finally realized that I was the one caring for both of us,” points to the slow process of that assessment. In contrast, another woman had lingering doubts about her personal strength: “I don’t know. I want to hope it makes me stronger … I guess it messed me up a bit in the head.”

Mental Distress

The qualitative interviews allowed us the opportunity to elicit the women’s perspectives on the ways in which the IPV affected their mental health. We know from the quantitative measures, at least preliminarily, that many of the women were depressed and/or experienced PTSD. The conversations with the women shed light on the extent of the mental toll the abuse exacted from them. Much of what we learned about the impact on mental health was identified in the code, “reactions to the abuse.” The subtheme of “shutting down” reflected the protective stance that some women took, although in some cases, the impact of the abuse was intense just the same. “The more I went on, the more I just shut down. I started believing everything he was saying—I am nothing, nobody wants me.” Similarly, the strategies of avoiding the abuser or adopting a stance of caution around him, were used by some women who stayed with the abuser but tried to minimize the episodes of abuse. “I just avoided him when he was high or drunk and tried to keep my distance. I made sure not to press any of the things I thought were triggers.”

Reactions of “blaming self” were common. The self-blame could stem from actually contributing to the abuse, or in some cases, for somehow allowing it to continue. One woman said: “I was a control freak, I wanted things my way. I might have started the verbal abuse. I don’t think I was mean, but my friends say I was mean to him, so I don’t know.” The result of this process of self-blame was often an enduring negative self-image. Several women described themselves as “stupid,” or engaged in self-recrimination, as this woman described it: “I don’t know how I let this happen to myself.” Even for women who were able to leave the abuser, self doubts lingered. One woman described her inner conflict this way: “I realize he was wrong and I didn’t deserve it or anything like that. And it upset me that I put up with a lot when I shouldn’t have.” The internalizing of the negative messages from the abuser took their toll on the mental health of women who, as noted earlier, saw themselves as “nothing.”

Additional coping responses that were evident included “taking a guarded stance” and “trying to detach emotionally” from the situation. For some, it stemmed from a belief that they had no choice, as one woman stated: “I felt like he was backing me up against a wall.” Other women figured out over time that as one woman acknowledged: “it’s just better to try to avoid the conflict altogether.” There were women who said they in fact, “did nothing,” or “walked on eggshells,” or generally kept quiet and did not engage the abuser in conversation for fear it would escalate. One woman described it this way:

When he got mad, he would get physically violent, choking, hitting, kicking, punching, everything. When I got mad I never voiced it or said anything about it because I didn’t want to get hurt. I just kept it in … [I] try to ignore my feelings and try to stay calm.

Mental Strength

Dealing with experiences of IPV during pregnancy was clearly a process for these women that left many of them feeling intense mental distress. For some women, however, the experiences and their “thinking through” what it meant for their sense of self led them to feel stronger. One woman in particular, acknowledging that it sounded “weird” to view the experience in a positive light, explained: “I don’t regret it, because a lot of times, I felt strong enough [to ask him to leave], I am kind of glad I went through it because it made me a better person … it made me deal with issues I never really knew I had.” While this reaction was rare, it did point to the inner mental strength that some women were able to draw upon.

Other women also talked about getting stronger, accepting the advice of supportive relatives, like the aunt of one woman who told her, “You are worth more than that.” This woman came to realize that the abuse could make her stronger even though, as she described it, it “messed her up a little bit in the head.” She went on to say: “I didn’t know what else to do … I didn’t know what a stable family looked like. I didn’t know how to work all those things because I never had that.” The realization for some that it was (as one woman said) “not normal” was a step forward that helped them deal with the abuse more effectively.

Parenting/Protecting the Children

Mothers spoke passionately about their efforts to protect their children from abuse. They would go to great lengths to prevent any hitting or yelling, including bargaining with the abuser. They were concerned about the impact of the violence on the children and they looked for signs that the children were being affected.

Impact of Violence Exposure on Children

The women’s concerns about the impact of the abuse on their children influenced their responses to the abuse. Whether or not the women’s children witnessed the abuse, or the mother’s assessment that the children were acting out because of the abuse, were key factors in determining how to she would respond to the abuse. A child acting violent for example, was considered a result of him seeing the abuse according to one woman who worried that: “You are spreading the message that abuse is OK.” A young daughter clinging to her mother but avoiding contact with others, was a concern of another mother that she attributed to the abuse in her family.

Hiding the Abuse/Protecting the Children

Some women looked for ways to control the children’s actual exposure to the abuse or the risk of the children becoming abused themselves. Using phrases like, “It always happened when they weren’t there,” but then including self in that circumstance: “We always kept that part hidden,” suggests a strategy of containment of the abuse. As several women stated: “We pretty much try not to do it in front of them” and “I wouldn’t let him hit my daughter.” Women also were intent on protecting the children from being abused. As one mother stated: “He would be holding my son really, really angry and grabbing him tighter and tighter. I’m like, just give me my baby, you can walk away, you can do whatever you want, just give me my son.”

Another woman described how her leaving the abuser was related to her son being able to tell the police what had occurred. Other women identified the children witnessing the abuse as the impetus to leave the abuser. Another woman described the attempts of her child to directly confront the abuser: “You need to get out of my mommy’s house because you are crazy.” As the women described the impact of the abusive episodes on children in the home, it became apparent that they wanted to see themselves as good parents and, in some cases, it mobilized them to make decisions or make changes. The relationship of these parenting decisions to the women’s perceptions of self was evident as the women talked of making decisions about the partner because of the children.

Contextual/Conditional Factors Influencing Changing Perception of Self

Perception of Severity

In examining the women’s stories of the abuse and the context of the abuse, we found that some women tended to minimize the abuse as “not that bad.” There was a noticeable lack of strong emotion and in some cases, no emotion, when talking about the abuse. When asked to compare their situations to others, most women in this sample tended to see their own abuse as less severe. It was striking that the comparisons they made were with extreme cases of abuse. For example, one woman said: “Most women are dead … or in fear for their safety” when discussing the severity of her abuse. Another woman who was physically abused stated: “I don’t think it is as bad” because she fought back. Several women agreed that if the abuse was emotional, that it was not as severe as the physical abuse that other women endured because, as one woman explained, she did not have any broken bones. When women did see their abuse situations as severe, they talked about the “danger” of being killed, and of intense fear. One woman said: “I thought I was going to die.”

Influence of Setting

As stated earlier, one of the aims of the study was to examine the role of the residential setting—urban or rural—in women’s responses to IPV, especially their help-seeking behaviors and willingness to use resources. Barriers to resources/help-seeking were apparent. For example, this woman is constrained by the level of personal knowledge of residents in a small town.

I haven’t called the police … you call the police, it’s local, everybody knows everybody … his father’s well respected … I would have got arrested … It’s not safe … everybody in town knows each other, every body is buddy-buddy … I went to them [police] a couple times about his threats, they went back and told his father … That’s not confidential.

Relationship with Abuser

Mixed feelings were expressed about the relationship with the abusive partner. Some women described wanting to be away from the abuser while also wanting him around for the children: “I want him here for the child,” one woman explained.

Family Support/Lack of Support

We examined the data for descriptions of how other adults in the family reacted to the abuse. It was a complicated process, with some women reluctant to tell their families about the abuse. This reluctance eliminated a potentially vital source of support for many women who seemed to be dealing with the abuse in isolation from family members. Some women described minimizing the situation to their own mothers and fathers, because they anticipated negative reactions. One woman said: “My mother found out, she didn’t tell me that she knew. To this day she would throw it in my face. I didn’t want her to know, because some people don’t know how to let it go.” Another woman, when asked how her mother reacted when she talked with her about it, stated: “Nothing really, she was just like, ‘Well, be careful.’ And that’s all she really told me.” Other family members were described as supportive and “willing to help,” but “they just want to make sure he’s not in the picture.”

DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

The strategies the women described in this study seemed to be aligned with their perceptions of self and therefore their overall mental health. These self-perceptions changed over time, sometimes to a view of strength, but sometimes to a view of self-doubt.

Depression and PTSD were assessed by the Edinburgh Depression Scale (Cox, Chapman, Murray, & Jones, 1996) and the Davidson Trauma Scale (Davidson et al., 2003), which further documented the alarming presence of these mental disorders in this sample. Almost half of the women in this study met the criteria for major depression or PTSD. This finding was supported by the qualitative findings and suggests that mental health interventions should be key components of an IPV intervention. To date, most interventions have targeted the engagement of the women in safety behaviors. This study and others have shown that the negative impact of depression (self-isolation, self-doubt, lack of emotional and physical energy) can significantly hamper a woman’s ability to adhere to recommended safety behaviors. In cases where there may be forced isolation of the abused woman by the abuser, the additive impact of isolation as a result of depressed mood, may put women at greater risk for inadequate support. These women in particular should receive supportive interventions for mood disturbances in order for them to develop the mental strength that is required to make difficult life decisions. In an earlier study of women’s decision making during the child-bearing cycle (Lutz, 2005), shame and stigma associated with IPV further isolated the women who did not reveal the abuse for fear of being “labeled” and judged. In the current study women frequently described themselves as “stupid” for staying with the abuser, and engaged in other negative self-appraisals. Living in an urban area was not necessarily appraised as more supportive for accessing IPV resources as compared to living in a rural area. This is an important consideration when facilitating referrals.

Women in this study evaluated severity of the abuse as “not as bad” as abuse experienced by other women. This tendency to minimize the effect of IPV is concerning since it may discourage them from seeking help. Additionally, women who self-blame and internalize negative self-images, may exhibit signs of depressed mood, further hampering their abilities to seek help. It is important to screen for depressed mood, particularly those who are “subthreshold” on depression measures and often missed by clinicians (Varma et al., 2007), since they too may be adversely affected in their support seeking. Past and current IPV can have a cumulative effect on mental health, and women can experience disabling mental distress, such as symptoms of depressed mood. This underscores the need to assess for and treat the continuum of depressive symptoms early in the pregnancy. Level of depression also has been shown to be correlated with family emotional support (Jones et al., 2005). The lack of family support for many of the women in this study, coupled with the isolation associated with depressed mood and the forced isolation by the abuser, suggests that an important target of intervention is intensive efforts to connect the women with a support network. It cannot be assumed that family members will understand the abuse or be supportive of the woman who is experiencing abuse. In another review, Orr (2004) found that isolated mothers with little support from the father of the baby do benefit from support provided by nurses or midwives. Home visits can be instrumental in providing the social support that these young women need to become more responsive to their children (Eshel, Daelmans, Cabralde-Mello, & Martines, 2006).

The finding that some women have mixed feelings toward the abuser supports the findings of an earlier qualitative study that found that women endured the abuse for the sake of the children (Lutz, 2005). Thus, the goal of ending the abuse by leaving the relationship can be a complex process for women whose mental strength has been compromised by repeated and long-term abuse. The women in the study reported here who were screened as having depression or PTSD were referred for counseling. However, as others have noted (Lutz, 2005), not all women who need it receive this counseling, and the process of obtaining it can be arduous. In this study almost half the women were diagnosed with depression or PTSD, a finding that supports other findings reported in the literature. For example, Varma and colleagues (2007) found that depressive symptoms were significantly associated with physical abuse and women who reported abuse were more likely than non-abused women to report depressive symptoms. Other studies have shown that that social support directly and indirectly buffers stress and decreases depression in pregnant and young parenting women (Sequin, Potvin, St. Denis, & Loiselle, 1995).

As Sharps et al. (2008) found, there is a lack of protocol for addressing intimate partner violence, as well as the mental health sequelae, in perinatal home visiting programs. Peckover (2002) found in her qualitative study of health visitors for new mothers that home visiting can be interpreted by women as policing rather than supporting. Further, this study indicated that the primary focus of these home visitors was “mothering,” which meant that even if the woman mentioned depression, it was assumed to be postnatal, or was not addressed at all. Moreover, all the women in Peckover’s study actively resisted telling the home visitor about the domestic violence. While not specifically addressed in Peckover’s study, the lack of assistance may be because the home visitor did not know how to intervene in the complex situation of domestic violence and depression.

Women’s abilities to make decisions or to use resources to keep themselves and their children safe can be enhanced by interventions that provide information about the dynamics of IPV, but also include efforts to decrease depression and PTSD. Nurses working with pregnant and post-partum women are the best professionals to intervene in the home because of their persuasive power (Olds, Sadler, & Kitzman, 2007) and are viewed by the general public as being competent and caring providers. They should, however, have adequate training based on solid epidemiological and theory based interventions in order to bring about the most effective adaptive behavior change (Olds et al., 2007). Perinatal nurse home visitors are in an ideal position to screen all women for IPV as well as the mental health impact of IPV. Moreover, they can be trained to effectively provide supportive interventions. Referrals to counseling for women who are assessed as having a major depressive disorder certainly should be done. However, interventions also are needed for women who may be classified as having minor depression or depressive symptoms.

Experiences of mental distress described by many of the women in this study were pervasive and intense. Some women tried to protect themselves by being on guard and/or emotionally detached, using strategies such as “shutting down,” and actively trying to physically not move or “do nothing” to provoke an abusive episode. They made efforts to deny their own feelings of anger, and some women described bargaining with the abuser to protect their children. Persistent episodes like this can result in women concluding that they are “stupid,” that they are “nothing” and that no one will provide support. These responses to the abuse suggest that, over time, the women’s mental health status would be adversely affected. Indeed, many of the women who described themselves in these negative terms tended to have higher scores on the measure of depression, and women who described themselves as “shutting down,” or not talking about the abuse tended to have higher scores on the PTSD measure. In contrast, women who were able to assert “I deserve better,” who were able to get past the self-blaming to some extent, were characterized as moving toward “mental strength.” These women tended to have lower scores on the depression and PTSD measures. It must be noted that the findings reported are limited by the small sample size and the single data collection point at baseline. Despite these limitations, however, the findings provided important direction for future research on the impact of IPV on women’s mental health. The findings also support the conclusion that women are actively engaged in trying to be good parents and that they go to great lengths to protect their children. Future analyses of the longitudinal data with the larger sample in this study will examine these relationships more closely and will also look for changes in depression and PTSD over time.

In summary, IPV during pregnancy is of paramount concern because the consequences of abuse are extensive and can gravely impact these women’s mental health. Nurses who come in contact with them because of the pregnancy can have a substantial impact on the IPV-related health issues of these women. Early recognition and subsequent care of pregnant women affected by IPV can facilitate more positive short- and long-term mental health outcome, including the development of mental strength and the resolution of mental distress.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: The authors report no conflict of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

Contributor Information

Linda Rose, Johns Hopkins University, School of Nursing, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Jeanne Alhusen, Johns Hopkins University, School of Nursing, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Shreya Bhandari, University of Missouri, Sinclair School of Nursing, Columbia, Missouri, USA.

Karen Soeken, University of Maryland, School of Nursing, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Kristen Marcantonio, Johns Hopkins University, School of Nursing, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Linda Bullock, University of Missouri, Sinclair School of Nursing, Columbia, Missouri, USA.

Phyllis Sharps, Johns Hopkins University, School of Nursing, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

References

- Abidin RR. Professional manual. 3. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1995. Parenting Stress Index. [Google Scholar]

- Astin MC, Lawrence KJ, Foy DW. Posttraumatic stress disorder among battered women: Risk and resiliency factors. Violence and Victims. 1993;8:17–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astin MC, Ogland-Hand SM, Coleman EM, Foy DS. Posttraumatic stress disorder and childhood abuse in battered women: Comparisons with maritally distressed women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:308–312. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.2.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock LFC. Unpublished dissertation. University of Otago; Christchurch, New Zealand: 1996. Effect of a low-cost health promotion program for pregnant women. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC, Garcia-Moreno C, Sharps P. Abuse during pregnancy in industrialized and developing countries. Violence Against Women. 2004;10(7):770–789. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC, Lewandowski LA. Mental and physical health effects of intimate partner violence on women and children. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1997;20:353–374. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J, Sharps P, Glass N. Risk assessment for intimate partner violence. In: Pinard GF, Pagani L, editors. Clinical assessment of dangerousness: Empirical contributions. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 136–157. [Google Scholar]

- Carbone-Lopez K, Kruttschnitt C, Macmillan R. Patterns of intimate partner violence and their associations with physical health, psychological distress, and substance use. Public Health Report. 2006;121(4):382–392. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascardi M, O’Leary KD, Schlee KA. Co-occurrence and correlates of posttraumatic stress disorder and major depression in physically abused women. Journal of Family Violence. 1999;14:227–250. [Google Scholar]

- Cox JL, Chapman G, Murray D, Jones P. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in non-postnatal women. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1996;39:185–189. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(96)00008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JR, Book SW, Colket JT, Tupler LA, Roth S, David D, Hertzberg M, Mellman T, Beckham JC, Smith RD, Davison RM, Katz R. Assessment of a new self-rating scale for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2003;27:153–160. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshel N, Daelmans B, Cabralde-Mello M, Martines JC. Responsive caregiving: Interventions and outcomes. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 2006;84(12):990–996. doi: 10.2471/blt.06.030163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazmararian JA, Lazorick S, Spitz AM, Ballard TJ, Saltzman LE, Marks JS. Prevalence of violence against pregnant women: A review of the literature. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;275:1915–1920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding JM. Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Family Violence. 1999;14:99–132. [Google Scholar]

- Houry D, Kemball R, Rhodes KV, Kaslow NJ. Intimate partner violence and mental health symptoms in African American female ED patients. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2006;24(4):444–450. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2005.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SM, Bogat GA, Davidson WS, von Eye A, Levendosky A. Family support and mental health in pregnant women experiencing interpersonal partner violence: An analysis of ethnic differences. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;36:97–108. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-6235-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levendosky AA, Leahy KL, Bogat GA, Davidson WS, von Eye A. Domestic violence, maternal parenting, maternal mental health, and infant externalizing behavior. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20(4):544–552. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.4.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz KF. Abuse experiences, perceptions, and associated decisions during the childbearing cycle. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2005;27(7):802–824. doi: 10.1177/0193945905278078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CC, Shei B, Myhr TL, DuMont J. Abuse: A risk factor for low birth weight? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2001;165(11):1567–1572. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon RD, Resick PA, Nishith P. An exploration of comorbid depression among female victims of intimate partner violence with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;82(2):315–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds D, Sadler L, Kitzman H. Program for parents of infants and toddlers: Recent evidence from randomized trials. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2007;48:355–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr S. Social support and pregnancy outcome: A review of the literature. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;47(4):842–855. doi: 10.1097/01.grf.0000141451.68933.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peckover S. Supporting and policing mothers: An analysis of the disciplinary practices of health visiting. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2002;38(4):369–377. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pico-Alfonso MA, Garcia-Linares MI, Celda-Navarro N, Blasco-Ros C, Echeburua E, Martinez M. The impact of physical, psychological, and sexual intimate male partner violence on women’s mental health: Depressive symptoms, posttraumatic stress disorder, state anxiety, and suicide. Journal of Women’s Health. 2006;15(5):599–611. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez MA, Bauer HM, McLoughlin E, Grumbach K. Screening and intervention for intimate partner abuse. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:468–474. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.5.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sequin L, Potvin L, St Denis M, Loiselle J. Chronic stressors, social support and depression during pregnancy. Obstet-Gynecol. 1995;85:583–589. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(94)00449-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharps P, Campbell J, Baty M, Walker K, Bair-Merritt M. Current evidence on perinatal home visiting and intimate partner violence. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 2008;37:480–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00267.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva MC, McFarlane J, Soeken K, Parker B, Reed S. Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in abused women in a primary care setting. Journal of Women’s Health. 1997;6:543–552. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1997.6.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, Earp JA, DeVellis R. Development and validation of the Women’s Experience with battering (WEB) scale. Women’s Health. 1995;1:273–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soeken K, McFarlane J, Parker B, Lominak MC. Testing of a clinical instrument to measure frequency, severity, and perpetrator of abuse against women. In: Campbell JC, editor. Empowering survivors of abuse: Health care for battered women and their children. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Kennedy CJ. Major depressive and post-traumatic stress disorder comorbidity in female victims of intimate partner violence. Affective Disorders. 2001;66:133–138. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00301-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SLLMS, Sugarman DB. The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Street AE, Gibson LE, Holohan DR. Impact of childhood traumatic events, trauma-related guilt, and avoidant coping strategies on PTSD symptoms in female survivors of domestic violence. Journal of Trauma Stress. 2005;18(3):245–252. doi: 10.1002/jts.20026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden PG, Thoennes N. Rep No NCJ-183781. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice; 2000. Full report of the prevalence, incidence, and consequences of violence against women. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari A, Chan KL, Fong D, Leung WC, Brownridge DA, Lam H, Wong B, Lam CM, Chau F, Chan A, Cheung KB, Ho PC. The impact of psychological abuse by an intimate partner on the mental health of pregnant women. An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2008;115(3):377–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01593.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma D, Chandra PS, Thomas T, Carey MP. Intimate partner violence and sexual coercion among pregnant women in India: Relationship with depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;102(1–3):227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitanza S, Vogel LC, Marshall LL. Distress and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in abused women. Violence Victims. 1995;10(1):23–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods S. Prevalence and patterns of post traumatic stress disorder in abused and post-abused women. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2000;21(3):309–324. doi: 10.1080/016128400248112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]