Abstract

A 34-year-old man was admitted to our hospital’s department of neurology because he had experienced a cryptogenic stroke followed by a transient ischaemic attack. The patient suffered from congenital hydrocephalus which was treated by ventriculoatrial shunt at 8 months of age. Twelve months later, because of recurrent infections, the catheter was partially removed and the distal segment was left in place. At admission, the transoesophageal echocardiogram showed severe pulmonary hypertension (80 mm Hg confirmed by invasive measurement). The distal tip of the catheter had migrated into the left atrium through a patent foramen ovale inducing a massive right-to-left shunt. We surgically removed the catheter and closed the interatrial defect. At 1 and 6 months follow-up the patient was asymptomatic with a reduced pulmonary hypertension (50 mm Hg). Since there was no other clinical finding responsible for the recurrent thromboembolic events, both at the pulmonary and cerebral level, the catheter was removed to prevent further complications.

BACKGROUND

Ventriculoatrial shunting is a well recognised procedure for the treatment of hydrocephalus. It is performed by the surgical creation of a communication between a cerebral ventricle and a cardiac atrium by means of a plastic tube, to permit drainage of cerebrospinal fluid for relief of hydrocephalus. The shunt is usually removed when it is no longer needed, to avoid complications.

This case is the first to demonstrate that a ventriculoatrial shunt positioned for a congenital hydrocephalus can be responsible not only for thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension but also for cryptogenic stroke and/or transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs).

Catheter removal was the only possible course of action to prevent future thromboembolic events and thus avoid further complications.

CASE PRESENTATION

In November 2007, a 34-year-old man was admitted to our department to undergo a transoesophageal echocardiogram (TOE) in order to evaluate the presence of a patent foramen ovale (PFO) underlying a cryptogenic stroke followed by a transient ischaemic attack that he had experienced a few months earlier.

The patient had suffered from hydrocephalus since birth. When he was 8 months old, he underwent surgical positioning of a ventriculoatrial shunt. Twelve months later, according to what the patient was able to report, he had several recurrent infections and the catheter was removed. Unfortunately, it was not possible to remove the distal part of the catheter that was cut and left in place.

At the age of 26, he was diagnosed with immune complex mediated glomerulonephritis and arterial hypertension. As a result he now suffers from chronic renal failure.

In November 2007 the patient was admitted to the department of neurology in our hospital for diagnostic evaluation because of cryptogenic stroke followed by frequent TIAs. In May 2007 the patient presented with an episode of TIA lasting half an hour with paresthesis of the face and right arm, and in August 2007 he presented with breathlessness, nausea, dizziness, right sided hemiparesis of the face and diplopia which resolved after 5 days. In the neurology department, no correlation between the ventriculoatrial shunt and the cerebrovascular events were initially considered.

The familial history was negative for thrombotic tendency.

Physical examination revealed normal and stable vital signs with dyspnoea on exertion (New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class II). Chest x ray, cranial computed tomography without contrast medium, carotid Doppler ultrasound, electrocardiography, coagulation parameters (prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), international normalised ratio (INR), fibrinogen, antithrombin III, fibrin D-dimer, C reactive protein (CRP)) and blood count, all produced normal findings.

We also performed a thrombophilic screening including functional assessment of protein C and protein S that resulted in normal values. Factor V and II values were normal and no genetic variants were present.

The findings of the chest x ray were negative.

Biochemical parameter examination revealed an increased concentration of creatinine (2.2 mg/dl, normal range 0.6–1.3 mg/dl) as a consequence of the glomerulonephritis.

Chest computed tomography, with and without contrast medium, showed thrombosis of the superior vena cava. A catheter was observed, starting from the superior vena cava and terminating in the right atrium.

Since there was no other explanation for the recurrent TIAs, the patient underwent a TOE and a transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) in order to evaluate the presence of a PFO as a cause of the cerebral ischaemia.

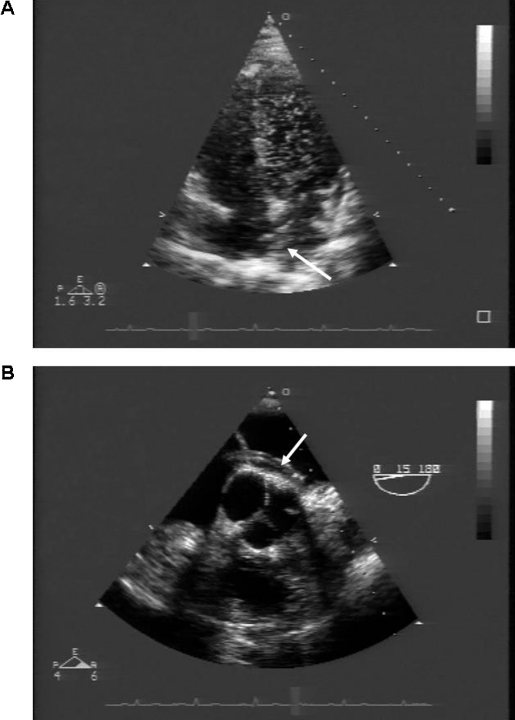

The TTE showed a massive right-to-left shunt by microbubble injection through the antecubital vein, with even the left ventricle deluged with bubbles (fig 1).

Figure 1.

(A) Transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrating a massive right-to-left shunt. The left ventricular chamber is completely filled with microbubbles after intravenous injection through the antecubital vein. The arrow indicates the catheter passing through the interatrial septum. (B) Transoesophageal echocardiogram clearly showing the catheter passing through the interatrial septum (arrow). The tip of the catheter has reached the mitral leaflets.

The TOE examination showed that the distal tip of the catheter had migrated into the left atrium throughout a patent foramen ovale (PFO) (fig 1) with right-to-left interatrial shunt confirmed by microbubble injection through the antecubital vein. Severe tricuspid regurgitation and severe pulmonary hypertension (80 mm Hg) were also found. Pulmonary hypertension was likely due to chronic recurrent pulmonary embolisms misdiagnosed until the current admission. Haemodynamic study confirmed the pulmonary hypertension with a mean wedge pressure of 15 mm Hg.

The superior vena cava thrombosis due to the persistence of the catheter was supposed to be the cause of misdiagnosed recurrent pulmonary embolism with secondary pulmonary hypertension.

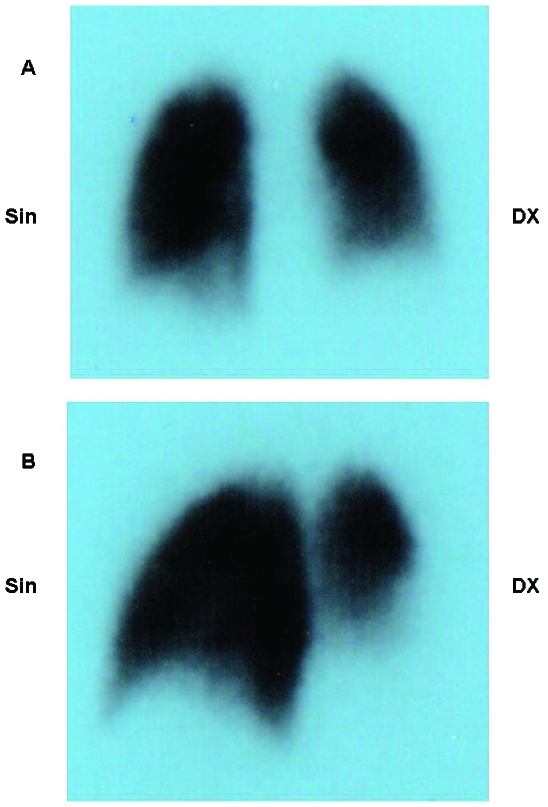

A pulmonary scan (185 MBq of the 99mTc-MAA intravenously) was then undertaken to confirm the presence of the pulmonary embolism and showed left lateral–basal and total right basal perfusion deficit. A reduced perfusion of the right superior segment was also found (fig 2).

Figure 2.

(A) Posterior view of the perfusional pulmonary scintigraphy scan. (B) Posterior oblique view of the perfusional pulmonary scintigraphy scan. Left lateral–basal and total right basal perfusion deficit is clearly visible. A reduced perfusion of the right superior segment was also found.

These findings strongly supported the hypothesis that the persistence of the catheter placed in the superior vena cava was causing a recurrent pulmonary and paradoxical thromboembolism. By passing through the PFO, the catheter had increased the possibility of a right-to-left shunt, which was even more likely after the development of pulmonary hypertension.

TREATMENT

We decided to remove the catheter to prevent future events. Since the catheter was not visible by x ray, a surgical approach was used instead of a percutaneous approach. The catheter was removed via standard median sternotomy and the PFO closed.

A few days after the intervention the patient was asymptomatic and discharged, and oral treatment with bosentan 125 mg twice daily was initiated.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

One month later the patient was still asymptomatic and a follow-up TTE showed normal left ventricular function, with tricuspid regurgitation and pulmonary hypertension (60 mm Hg) reduced in comparison to pre-surgery findings. A follow-up at 6 months demonstrated a further reduction in the pulmonary hypertension (50 mm Hg).

DISCUSSION

Ventriculoatrial shunting is a well recognised procedure for treatment of hydrocephalus. The shunt is usually removed when it is no longer needed, to avoid complications.

Obstruction and infection are the most frequent complications.1–4 Other complications include chronic pulmonary thromboembolism,5–8 cardiac tamponade, endocarditis of the tricuspid valve,1 superior vena cava obstruction, and immune complex mediated glomerulonephritis due to recurrent infections.9–11

In this case, recurrent infections of the catheter required its removal. Unfortunately the distal part of the catheter was left in place. At that time the surgeon thought that it would not have caused any significant consequences, reassuring the parents about the safety of this kind of procedure.

However, the patient was admitted at the age of 34 to our hospital with several health problems related to the ventriculoatrial shunting performed for his hydrocephalus. The chronic renal failure was likely due to an immune mediated glomerulonephritis as described in the literature as a consequence of shunting for hydrocephalus even years after a chronically infected ventricular shunt.9–11 Some years later he was admitted for recurrent cerebrovascular ischaemic events.

However, no data are available in the literature about thromboembolic stroke and/or transient ischaemic attacks related to a ventriculoatrial shunt.

Our patient was admitted for detection of a PFO, which is present in 40% of patients with cryptogenic stroke and may be associated with paradoxical emboli to the brain.12

Before performing the TOE to diagnose whether or not the TIAs were due to the persistence of the PFO with paradoxical embolism, there was no evidence that the catheter inserted for the shunt had crossed the interatrial septum, thus creating the possibility of paradoxical embolism. The demonstration of the catheter crossing the PFO was also associated with a basal right-to-left shunt. In fact, there was evidence of a severe pulmonary hypertension which in turn led to an increase of right atrial pressure causing basal right-to-left shunt.

Since the catheter had also caused thrombus formation in the superior vena cava, we thought that the pulmonary hypertension was related to chronic and recurrent thromboembolic events that had not been diagnosed in the past. Pulmonary thromboembolism most commonly originates from deep venous thrombosis of the legs, and ranges from asymptomatic, incidentally discovered emboli to massive embolism causing immediate death. Chronic sequelae of venous thromboembolism (deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism) include the post-thrombotic syndrome13 and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.14

Annually as many as 300 000 people in the USA die from acute pulmonary embolism15 and the diagnosis is often not made until autopsy.16,17 Non-lethal pulmonary embolism is also often misdiagnosed.

The pulmonary scan (185 MBq of the 99mTc-MAA intravenously) confirmed the presence of the pulmonary embolism and showed left lateral–basal and total right basal perfusion deficit. A reduced perfusion of the right superior segment was also found.

The thrombophilic screening was completely negative. Therefore we decided to remove the catheter and to close the PFO to reduce the risk for recurrent pulmonary and/or paradoxical embolism.

The literature reports the successful retrieval of the detached intracardiac segment of an atrial catheter by a percutaneous transvenous approach.18–21 Unfortunately, since the catheter was not visible at x ray, we could not try to remove it percutaneously and the patient underwent a surgical procedure of catheter removal and closure of the PFO by standard median sternotomy, cardiopulmonary bypass and right atriotomy.

This paradigmatic case shows how a negligent approach can be extremely deleterious, causing life threatening diseases that can present years after the wrong decision has been made.

Leaving part of the catheter inserted to treat the hydrocephalus resulted in a number of problems that affected the physical ability and the prognosis of our patient. He suffers from chronic renal failure (most likely due to immune mediated glomerulonephritis), cerebral ischaemia (from paradoxical emboli), and pulmonary hypertension (derived from recurrent and misdiagnosed pulmonary thromboembolic events arising from superior vena cava thrombi). All of these complications are related to the ventriculoatrial shunt as described in the literature.

This is the first demonstration that a ventriculoatrial shunt positioned for a congenital hydrocephalus can be responsible not only for thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension but also for cryptogenic stroke and/or TIAs.

Catheter removal was the only possible course of action to take in order to prevent future thromboembolic events, thus avoiding further complications. Oral treatment with bosentan helped to reduce pulmonary hypertension during the follow-up, leading to an improvement in symptoms. The patient was in NYHA functional class I at both 1 and 6 months follow-up.

LEARNING POINTS

Ventriculoatrial shunt for congenital hydrocephalus can induce important complications such as obstruction, infection, chronic pulmonary thromboembolism, cardiac tamponade, endocarditis of the tricuspid valve, superior vena cava obstruction and immune complex mediated glomerulonephritis due to recurrent infections. When it is no longer needed, it is very important to remove the catheter completely in order to avoid future severe complications.

This is the first demonstration that a ventriculoatrial shunt is able to induce pulmonary as well paradoxical embolism after crossing a patent foramen ovale causing cryptogenic stroke and/or TIAs.

Complete catheter removal was necessary to prevent future thromboembolic events, thus avoiding further complications.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication

REFERENCES

- 1.Bellamy CM, Roberts DH, Ramsdale DR. Ventriculo-atrial shunt causing tricuspid endocarditis: its percutaneous removal. Int J Cardiol 1990; 28: 260–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borgbjerg BM, Gjerris F, Albeck MJ, et al. A comparison between ventriculo-peritoneal and ventriculo-atrial cerebrospinal fluid shunts in relation to rate of revision and durability. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1998; 140: 459–64; discussion 465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langen HJ, Alzen G, Avenarius R, et al. [Diagnosis of complications of ventriculo-peritoneal and ventriculo-atrial shunts]. Radiologe 1992; 32: 333–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samtleben W, Bosch T, Bauriedel G, et al. [Internal medicine complications of ventriculoatrial shunt]. Med Klin (Munich) 1995; 90: 67–71 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byard RW. Mechanisms of sudden death and autopsy findings in patients with Arnold-Chiari malformation and ventriculoatrial catheters. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 1996; 17: 260–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kadar K, Hartyanszky I, Kiraly L, et al. Right heart thrombus in infants and children. Pediatr Cardiol 1991; 12: 24–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGrail KM, Muzzi DA, Losasso TJ, et al. Ventriculoatrial shunt distal catheter placement using transesophageal echocardiography: technical note. Neurosurgery 1992; 30: 747–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milton CA, Sanders P, Steele PM. Late cardiopulmonary complication of ventriculo-atrial shunt. Lancet 2001; 358: 1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Black JA, Challacombe DN, Ockenden BG. Nephrotic syndrome associated with bacteraemia after shunt operations for hydrocephalus. Lancet 1965; 2: 921–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kubota M, Sakata Y, Saeki N, et al. A case of shunt nephritis diagnosed 17 years after ventriculoatrial shunt implantation. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2001; 103: 245–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rifkinson-Mann S, Rifkinson N, Leong T. Shunt nephritis. Case report. J Neurosurg 1991; 74: 656–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casaubon L, McLaughlin P, Webb G, et al. Recurrent stroke/TIA in cryptogenic stroke patients with patent foramen ovale. Can J Neurol Sci 2007; 34: 74–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schulman S, Lindmarker P, Holmstrom M, et al. Post-thrombotic syndrome, recurrence, and death 10 years after the first episode of venous thromboembolism treated with warfarin for 6 weeks or 6 months. J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4: 734–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pengo V, Lensing AW, Prins MH, et al. Incidence of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 2257–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silverstein MD, Heit JA, Mohr DN, et al. Trends in the incidence of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a 25-year population-based study. Arch Intern Med 1998; 158: 585–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergqvist D, Lindblad B. A 30-year survey of pulmonary embolism verified at autopsy: an analysis of 1274 surgical patients. Br J Surg 1985; 72: 105–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sandler DA, Martin JF. Autopsy proven pulmonary embolism in hospital patients: are we detecting enough deep vein thrombosis? J R Soc Med 1989; 82: 203–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furui S, Yamauchi T, Makita K, et al. Intravascular foreign bodies: loop-snare retrieval system with a three-lumen catheter. Radiology 1992; 182: 283–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grabenwoeger F, Dock W, Pinterits F, et al. Fixed intravascular foreign bodies: a new method for removal. Radiology 1988; 167: 555–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Propp DA, Cline D, Hennenfent BR. Catheter embolism. J Emerg Med 1988; 6: 17–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tatsumi T, Howland WJ. Retrieval of a ventriculoatrial shunt catheter from the heart by a venous catheterization technique. Technical note. J Neurosurg 1970; 32: 593–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]