Abstract

Many chiropractors believe that chiropractic treatments are effective for gastrointestinal disorders. The aim of the present systematic review was to critically evaluate the evidence from controlled clinical trials supporting or not supporting this notion. Six electronic databases were searched for relevant studies. No limits were applied to language or publication date. Prospective, controlled, clinical trials of any type of chiropractic treatment for any type of gastrointestinal problem, except infant colic, were included. Only two trials were found – one was a pilot study, and the other had reached a positive conclusion; however, both had serious methodological flaws. There is no supportive evidence that chiropractic is an effective treatment for gastrointestinal disorders.

Keywords: Alternative medicine, Chiropractic, Effectiveness, Evidence, Gastroenterology

Abstract

De nombreux chiropraticiens pensent que les traitements chiropratiques sont efficaces pour soigner les troubles gastro-intestinaux. La présente analyse systématique visait à procéder à une évaluation critique des données probantes tirées d’essais cliniques contrôlés pour ou contre cette notion. Le chercheur a fouillé six bases de données électroniques pour trouver des études pertinentes. Il n’a appliqué aucune limite de langue ou de date de publication. Il a inclus les essais cliniques prospectifs contrôlés sur tous les types de traitement chiropratique, en présence de tous les types de trouble gastro-intestinal, sauf les coliques des nourrissons. Il n’a trouvé que deux essais, un essai pilote et un autre qui tirait une conclusion positive. Cependant, tous deux étaient enta-chés de graves anomalies méthodologiques. Aucune donnée probante n’étaye que la chiropraxie constitue un traitement efficace des troubles gastro-intestinaux.

Chiropractic can be defined as “a system of healthcare which is based on the belief that the nervous system is the most important determinant of a person’s state of health” (1). The hallmark treatment of chiropractic is spinal manipulation (2). Chiropractors mostly treat spinal problems, but many believe that chiropractic is also effective for a range of nonspinal conditions (3).

Some chiropractors claim that, after treating patients with spinal manipulation for spinal problems, symptoms related to the digestive system frequently improved (4). According to a survey conducted in 2004 by the United Kingdom (UK) General Chiropractic Council (3), 57% of all UK chiropractors believed that their treatments were effective for digestive disorders. According to a similar survey conducted in 2007 (5), 61% of UK chiropractors believed that gastrointestinal complaints are “effectively treatable by chiropractic methods”.

The present review attempts to establish supportive evidence for or against this notion based on the totality of the evidence from clinical trials.

METHODS

The following databases were searched from their respective inceptions to March 2010: Embase (via OVID), Medline (via OVID, Cinahl (via EBSCO), AMED (via EBSCO), the Cochrane Library (via Wiley) and The Index of Chiropractic Literature. The search strategy included freeword search terms and MeSH, which were adapted for each database. The bibliographies of all relevant articles were manually searched. No limits were applied to language. The search results were exported into a single reference manager file.

To be included, an article was required to pertain to a prospective, controlled clinical trial of any type of chiropractic treatment for any type of gastrointestinal problem. Studies of infant colic were, however, excluded because a recent systematic review (6) previously addressed this issue. Data from all included studies were extracted according to predefined criteria, with their methodological quality assessed using the Jadad score. A meta-analysis was considered; however, due to the paucity and heterogeneity of the primary data, the plan was abandoned.

RESULTS

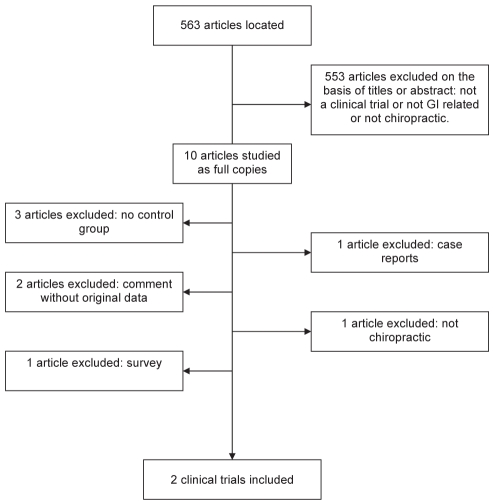

The search located 563 articles, the vast majority of which were excluded on the basis of reading their titles or abstracts. Two of 17 articles that were potential clinical trials and met the aforementioned inclusion criteria were reviewed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of included studies. GI Gastroenterology

Hains et al (7) recruited 62 patients who experienced gastroesophageal reflux disease for at least three months as diagnosed “by a physician or doctor of chiropractic” (7). Group 1 was randomly assigned to receive 20 sessions of spinal manipulation plus ischemic compression (a chiropractic myofascial technique), group 2 received purely spinal manipulation and group 3 received purely ischemic compression. The authors did not provide details regarding patient history or concomitant treatments. The duration of the typical treatment phase was seven weeks (three sessions per week). Outcomes were recorded via patient questionnaire and numerical rating scales of symptom severity. At the end of the treatment phase, group 1 reported an average improvement of 66%, group 2 40% and group 3 65%. The authors concluded that “both spinal manipulation and ischemic compression were found to be effective treatments for patients experiencing gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms”. This trial received a Jadad score of 1.

Pikalov and Kharin (8) treated 11 patients with duodenal ulcers with spinal manipulations (three to 14 sessions in total) plus conventional treatments. Twenty-four patients treated conventionally served as controls. No details of previous treatments or diagnostic tests were provided. Outcomes were “evaluated using clinical parameters” (no further details supplied). The spinal manipulation group was reported to experience clinical remission earlier than the control group. The authors concluded that “this pilot study indicates a very promising direction for research in the conservative care of duodenal ulcers”. This nonrandomized study scored zero points on the Jadad scale.

DISCUSSION

The results of the present systematic review showed that very few controlled clinical trials of chiropractic treatments for gastrointestinal problems have been published. The two included studies were both of very poor methodological quality; one (7) scored 1, and the second (8) scored zero points on the Jadad scale.

The study by Hains et al (7) failed to control for nonspecific effects including natural history of the disease, regression toward the mean and placebo effects. Thus, the seemingly positive results may have been entirely unrelated to the interventions. Moreover, essential details regarding the patient population were missing. The authors’ conclusions do not seem justified – both treatments may have been similarly ineffective.

The pilot study by Pikalov and Kharin (8) was not randomized. Its sample size was very small and there was no attempt to control for nonspecific effects. Moreover, unclear and subjective criteria for evaluating the clinical outcome were used, and essential patient details were not provided. The authors were aware of some of these limitations and drew adequately cautious conclusions.

Chiropractors adjust ‘subluxtions’ (ie, minimal perceived malalignments of the vertebrae). Such abnormalities – if they exisit at all – have no proven pathophysiological significance (9). The dictum of DD Palmer (10), the founder of chiropractic, that “95% of all diseases are caused by displaced vertebrae, the remainder by luxations of other joints” is clearly not correct. Yet many chiropractors still seem to adhere to it, arguing that “it seems unreasonable to limit the horizons of clinical chiropractic unnecessarily…” (11).

Given the paucity and the poor quality of the existing evidence, this attitude seems questionable, particularly because some chiropractic treatments are associated with considerable risks (2). Therapeutic claims should be supported by sound evidence in all areas of health care. The notion that chiropractic is an effective treatment for gastrointestinal problems is not supported by good evidence.

Unsubstantiated therapeutic claims made by chiropractors are not confined to gastroenterology. Many investigations have disclosed claims that are not based on good evidence (12–17). It is, therefore – high time, one might argue – that the chiropractic profession worldwide draws the correct conclusions from this evidence and adheres to the basic principles of evidence-based medicine and medical ethics.

CONCLUSION

Although many chiropractors seem to believe otherwise, there is no supportive evidence to show that chiropractic treatments are effective for gastrointestinal problems.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author is indebted to Leala Watson for conducting the literature searches.

Footnotes

FUNDING/CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: The author has no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Segen JC. Dictionary of alternative medicine. Stamford: Appleton and Lange; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ernst E. Chiropractic: A critical evaluation. J Pain Sympt Man. 2008;35:544–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.General Chiropractic Council. Consulting the profession: A survey of UK chiropractors. London: General Chiropractic Council; 2004. [(Accessed on October 6, 2010)]. < http://www.gcc-uk.org/files/link_file/ConsultTheProfession.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leboeuf-Yde C, Axén I, Ahlefeldt G, Lidefelt P, Rosenbaum A, Thurnherr T. The types and frequencies of improved nonmusculoskeletal symptoms reported after chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1999;22:559–64. doi: 10.1016/s0161-4754(99)70014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pollentier A, Langworthy JM. The scope of chiropractic practice: A survey of chiropractors in the UK. Clin Chiropractic. 2007;10:147–55. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ernst E. Chiropractic spinal manipulation for infant colic: A systematic review of randomised clinical trials. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63:1351–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hains G, Hains F, Descarreaux M. Gastroesophageal reflux disease, spinal manipulative therapy and ischemic compression: A preliminary study. J Am Chiropract Assoc. 2007;44:7–19. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pikalov AA, Kharin VV. Use of spinal manipulative therapy in the treatment of duodenal ulcer: A pilot study. J Manip Physiol Ther. 1994;17:310–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mirtz TA, Morgan L, Wyatt LH, Greene L. An epidemiological examination of the subluxation construct using Hill’s criteria of causation. Chiropr Osteopat. 2009;17:13. doi: 10.1186/1746-1340-17-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Homola S. Chiropractic: History and overview of theories and methods. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;444:236–42. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000200258.95865.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chance MA, Peters RE. While the jury is out. Chiro J Australia. 1997;27:97. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dew K. Apostasy to orthodoxy: Debates before a commission of inquiry into chiropractic. Sociol Health Illn. 2000;22:310–30. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grod JP, Sikorski D, Keating JC. Unsubstantiated claims in patient brochures from the largest state, provincial, and national chiropractic associations and research agencies. J Man Phys Ther. 2001;24:514–9. doi: 10.1067/mmt.2001.118205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sikorski D, Grod JP. The unsubstantiated website claims of chiropractic colleges in Canada and the United States. J Chiropr Educ. 2003;17:113–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holt S. The responses of alternative practitioners when approached about common childhood illnesses. J New Zealand Med Assoc. 2008;121:114–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ernst E. The ethics of chiropractic. New Zealand Med J. 2008;121:96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ernst E, Gilbey A. Chiropractic claims in the English-speaking world. New Zealand Med J. 2010;123:36–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]