Abstract

A mixed-mode reversed-phase/weak cation exchange (RP/WCX) phase has been developed by introducing a small amount of carboxylate functionality into a hydrophobic hyper-crosslinked (HC) platform. This silica based HC-platform was designed to form an extensive polystyrene network completely confined to the particle's surface. The fully connected polymer network prevents the loss of bonded phase, which leads to superior hydrolytic stability of the new phase when compared to conventional silica based phases. Compared to previously introduced HC phases the added carboxylic groups impart a new weak cation exchange selectivity to the base hydrophobic HC platform. The phase thus prepared shows a mixed-mode retention mechanism, allowing for both neutral organic compounds and bases of a wide polarity range to be simultaneously separated on the same phase under the same conditions. In addition, the new phase offers the flexibility that gradients in organic modifier, pH or ionic competitors can be used to affect the separation of a wide range of solutes. Moreover, the inherent weak acid cation exchange groups allow formic and acetic acid buffers to be used as eluents thereby avoiding the mass spectrometric ionization suppression problems concomitant to the use of non-volatile additives such as strong amine modifiers (e.g. triethylamine) or salts (e.g. NaCl) to elute basic solutes from the strong cation exchange phase which was previously developed in this lab. The use of the new phase for achieving strong retention of rather hydrophilic neurotransmitters and drugs of abuse without the need for ion pairing agents is demonstrated.

Keywords: HPLC, Stationary phase, Reversed phase, Cation exchange, Selectivity, Basic analytes, Mixed mode retention, Hydrophobically assisted ion exchange

1. Introduction

The ultimate goal of any separation is to achieve acceptable resolution (Rs) in a reasonable time. As the most essential metric of separation power in chromatography, Rs can be expressed in terms of three parameters efficiency (N), chromatographic selectivity (α) and retention (k’), where for simple mixtures the most significant impact comes from selectivity [1-3]. Useful method development strategies for optimizing selectivity are based on manipulating the experimental conditions, such as the mobile phase compositions (%B) or mobile phase type [4-9] , stationary phase type [8,9] and sometimes temperature [2,10,11]. Previously, because of the long-held belief that retention and selectivity in RPLC are dominated by the mobile phase (i.e. the solvophobic theory [12]), major emphasis was usually given to optimizing mobile phases (e.g. %B, type of organic modifier) while the effect of the type of stationary phase on selectivity has been very much underestimated. However, with the further elucidation of retention mechanisms in RPLC, an increasing number of reports indicate that the different types of RPLC materials also play an important role in selectivity optimization [13-16]. Recently, it has been suggested by several studies [8,9,17] that varying the type of stationary phases is in fact one of the most effective ways to change chromatographic selectivity.

In response, many types of novel chemically bonded phases have been developed [18-22]. Among them, a new type of mixed-mode stationary phases has recently attracted increasing attention [23-26]. In principle, this group of stationary phases is designed by combining two or more orthogonal separation mechanisms such as non-specific hydrophobic interaction and specific electrostatic interactions. The resulting materials often tend to offer quite different selectivity from conventional ODS columns where the separation and selectivity are dominated largely by hydrophobic interactions [27-31]. As a result, the use of these mixed-mode phases, often referred as “orthogonal” phases, can provide an alternative and complementary separation for many analyses performed on the most frequently used conventional C8 or C18 columns [27-30]. This is very important for method development in both analytical and preparative HPLC where dramatically different selectivity is required or is highly advantageous. For example, for compounds that are very difficult to separate on traditional ODS phases, the elution order of solutes often differs on the “orthogonal” phases thus providing enhanced selectivity [32]. This can aid in identification, proof of purity and quantitation. Hence many have found them extremely useful when incorporated into a method development screening process [8,9,32-36]. One the other hand, a change in elution order can also be useful in preparative HPLC. It may enable the elution of a minor component in front of a major component upon using a unique phase, thereby making collection and/or quantitation considerably easier. Also in two dimensional chromatographic separations, the column in the second dimension must be very different from the column in the first dimension to achieve high peak capacities [37].

In fact, mixed-mode phases are not a new concept. It is well established in solid phase extraction materials [38] and capillary electrochromatography [31,39-44] where a reversed phase is usually combined with an ion exchange phase. In LC, the early mixed-mode RP/ion-exchange phases have been developed predominantly based on organic polymer because of their good pH stability and the relative ease of introducing cation exchange sites [45]. However, these purely organic polymeric phases generally have low plate counts compared to silica based stationary phases [46] and equilibration upon a change in solvent can be slow [46,47]. More recently, several examples of silica based mixed-mode RP/ion-exchange phases have also been reported [23-30,48-50]. For example, Nogueira and Lindner synthesized a reversed-phase/weak anion exchange (RP/WAX) material by grafting N-(10-undecenoyl) -3-aminoquinuclidine onto thiolfunctionalised silica particles [23-25] or monoliths [26]. It has several distinct interaction sites including a hydrophobic alkyl chain (hydrophobic domain), embedded polar functional groups (hydrophilic domains), and a terminal bicyclic quinuclidine ring as an anion exchange site on silica. A reversed-phase/weak cation exchange (RP/WCX) silica phase (Primesep™) has also been introduced, with ionic carboxylate groups embedded within hydrophobic ligands according to the manufacture [51]. These phases offer very unique selectivity and concurrently enhanced mass loading capacity compared to traditional C8 or C18 phases [23-25]. However, the hydrolytic stability of the material can be wanting. The hydrophobic organic layer on the silica surface was mainly bridged by some polar groups (e.g. amide and sulfide). The rather facile hydrolysis of these groups, especially at elevated temperatures, can lead to continuous loss of the bonded phases and thus limit the application of the phase under acidic conditions.

In the present study, a novel type of ultra stable highly efficient mixed-mode reversed-phase/weak cation exchange (RP/WCX) phase based on the previous HC-platform will be described. This silica based HC-platform was designed to form an extensive polystyrene network completely confined to the particle's surface [52-57]. Although the chemistry involved in making these cross-linked functionalized aromatic layer is similar to that employed by Davankov [58-60], our work is fundamentally different in that Davankov's materials are totally organic polymers whereas as our materials are based on modified silica with a surface confined layer of highly crosslinked aromatic polymer. The fully connected polymer network prevents the loss of bonded phase, which leads to a superior hydrolytic stability in acid of these new phases when compared to conventional silica based phases [52-56]. In this work, the HC-platform is carboxylated with ethyl phenyl acetate. The added carboxylic groups provide weak cation exchange selectivity to the hydrophobic HC platform. The phase thus prepared shows a mixed-mode retention mechanism, allowing for both neutral organic compounds and charged bases simultaneously separated on the same phase under the same conditions. The preparation and characterization of this new packing material are studied. Its chromatographic properties are also evaluated.

2. Experimental Section

2.1 Chemicals

Reaction reagents: dimethyl chloromethylphenylethylchlorosilane (DM-CMPES) was obtained from Gelest Inc. (Tullytown, PA). Styrene heptamer (SH) is a polystyrene standard (number average molecular weight Mn: 800) purchased from Scientific Polymer Products Inc. (Ontario, NY). Diisopropylethylamine (≥ 99%), Chloromethylmethyl ether (CMME, CH3OCH2Cl), SnCl4 (99%) and ethyl phenyl acetate were obtained from Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI)

Reaction solvents: Dichloromethane was obtained from Mallinkrodt (HPLC grade, Phillipsburg, NJ) and dried by MB-SPS (Solvent Purification System from MBRAUN, Stratham, NH) before use. ACS grade tetrahydrofuran (THF), acetone, 37.6% HCl and HPLC grade methanol (MeOH), isopropanol (IPA) were also obtained from Mallinkrodt (Phillipsburg, NJ). Anhydrous 1,2-dichloroethane (99+%, ACS grade) was obtained from Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI).

HPLC buffers and solvents: ACS grade lithium chloride and potassium chloride were obtained from Aldrich, 50% formic acid, acetic acid and ammonium acetate are HPLC grade reagents from Fluka (Allentown, PA). HPLC acetonitrile (MeCN) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). HPLC water was prepared by purifying house deionized water with a Barnstead Nanopure II deionizing system with an organic-free cartridge and run through an “organic-free” cartridge followed by a 0.45 μm Mini Capsule filter from PALL (East Hills, NY).

HPLC solutes: Ephedrine, methamphetamine, methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA), methylenedioxyethylamphetamine (MDEA), methcathinone, cathinone were purchased from Cerilliant (Round Rock, TX) as 1 mg/mL solutions of drug in methanol. The alkylphenone homologs, the 22 solutes for the LSER study [61] and the 16 solutes for hydrophobic subtraction method study (uracil, acetophenone, benzonitrile, anisole, toluene, ethylbenzene, 4-nitrophenol, 5-phenylpentanol, 5, 5-diphenylhydatoin, chalcone, N, N-dimethylacetamide, N, N-diethylacetamide, 4-n-butylbenzoic acid, mefenamic acid, nortriptyline, and amitriptyline) were of reagent grade or better and were used as obtained from Sigma-Aldrich without further purification. Standards of the amphetamines, opiates, and benzodiazapine drugs used for selectivity study were obtained from the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension (BCA) as 1 mg/mL stock solutions in methanol (originally from Ceriliant (Round Rock, TX, USA)). Uracil was purchased from Sigma and dissolved in pure water at a concentration that gave adequate signal to determine column dead volume.

Silica substrate: Type-B HiChrom silica particles and ACE C18 particles were gifts from Mac-Mod, Inc (Chadds Ford, PA). The particle diameter, surface area, and pore diameter of the particles are 5.0 microns, 250 m2/g, and 150 Å respectively.

2.2 Synthesis of HC-COOH Phases

2.2.1 Silanization

All glassware was rigorously cleaned, rinsed thoroughly with HPLC water, dried at 150 °C overnight and cooled under nitrogen prior to use. 10 grams of type-B HiChrom silica were dried under vacuum at 160 °C for 12 hours prior to use. After cooling to room temperature under vacuum, the dried silica was slurried in fresh dichloromethane at a ratio of 5 ml/g (of silica). The slurry was sonicated under vacuum in a 250 mL roundbottom flask for 15 minutes to fully wet the pores. After sonication, diisopropylethylamine was added to the slurry as the “acid scavenger” and silanization catalyst at a concentration of 3.2 μmoles/m2 (of silica). Then, 16 μmoles/m2 (of silica) of DM-CMPES was added to the stirring slurry. An activated alumina column was used to cap the condenser to prevent water contamination. The reaction mixture was refluxed at 50 °C for 4 hours. Next, the silica particles were washed sequentially with 350 mL aliquots of dichloromethane, THF, MeOH, MeOH/water, and acetone. After washing, the silica was air dried overnight at room temperature before the next step was performed.

2.2.2 Synthesis of Hyper-Crosslinked Platform

The hyper-crosslinked platform was prepared by a series of two SnCl4 catalyzed Friedel-Crafts alkylations on type-B HiChrom silica that has been silylated with DMCMPES. The detailed reaction conditions are listed in Table 1.1 and can be found in our previous publications [53,54].

Table 1.

The Friedel-Craft Reaction Conditions Used in the Preparation of the Hyper-Crosslinked platform

| Reaction | Phase Designation | Reagents Used | Catalyst Type | Reaction Temperature (°C) | Reaction Time (hours) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Crosslinking | SH-DMCMPES | SHa (2 ×) | SnCl4d (10 ×) | 80 | 3 |

| Secondary Crosslinking | Hyper-Crosslinked platform | CMMEb (10 ×) | SnCl4d (10 ×) | 50 | 1.5 |

| Derivatization | HC-COOH | Ethyl phenyl acetatec (10 ×) | SnCl4d (10 ×) | 80 | 1.0 |

SH: styrene heptamer. The mole ratio of styrene heptamer to chloromethyl group on DMCMPES is 2.

CMME: chloromethylmethyl ether. The mole ratio of CMME to chloromethyl group on DMCMPES is 10.

The mole ratio of Ethyl phenyl acetate to chloromethyl group on DMCMPES is 10.

The mole ratio of SnCl4 to chloromethyl group on DMCMPES is 10.

Other detailed procedures are described in Section 2.2.2

2.2.3 Derivatization of HC-COOH phase

10 grams of alkylated type-B HiChrom silica were put into a 250 mL two-neck round-bottom flask and sonicated under vacuum with 92 mL of anhydrous 1,2-dichloroethane for 10 minutes, followed by addition of 11 grams of ethyl phenyl acetate. Next, 7.9 mL of SnCl4 dissolved in 8 mL of anhydrous 1, 2-dichloroethane was injected into the heated stirred slurry through a rubber septum seal on one neck of the flask. The reaction mixture was refluxed at 80 °C for 1 hour. After reaction, the particles were filtered and washed sequentially with 350 mL of 1,2-dichloroethane, THF, THF with 10% (v/v) concentrated hydrochloride, MeOH, and acetone.

2.3 Gradient Acid Washing

After synthesis, the hyper-crosslinked phase HC-COOH was pre-conditioned by gradient acid washing at 150°C as described in our previous publications [53,54]. After gradient washing, the column was flushed with 50/50 IPA/water thoroughly and then unpacked to dry the particles.

2.4 Elemental Analysis

A small amount of stationary phases after each step was sent for carbon, hydrogen, and chlorine analysis conducted by Atlantic Microlabs, Inc. (Norcross, GA).

2.5 Column packing

HC particles were packed into a 5.0 × 0.46 cm column for further characterization. The particles were slurried in a mixture of n-BuOH/DMSO/THF (v/v/v) 7.5/7.5/85 (1.0 g/22.5 mL) and sonicated for 20 minutes prior to packing. Columns were packed by the downward slurry technique using a Haskel 16501 high-pressure pump to drive methanol through the column. The packing pressure was slowly increased from 500 psi to 7000 psi during the first 2 minutes of packing, and maintained at the highest pressure until about 150 mL of solvent were collected before the pressure was released.

2.6 Characterization of the cation-exchange capacity

The cation exchange capacity of the HC-COOH phase was assessed by the frontal uptake method [62], wherein the amount of surface cation-exchange sites on the HC-COOH phase were measured at different pHs. In order to keep the conditions consistent with the chromatographic conditions used in our study of the retention of basic compounds, the column was first washed by 60 ml of 24/76 ACN/water with 10 mM potassium acetate at pH of 4.0, 5.0 or 6.0 (buffered by acetic acid) at 1 ml/min to saturate the cation exchange sites with potassium ions. The column was then detached and the pumping system was purged with 24/76 ACN/water with 10mM lithium acetate at the same pH. After the system was thoroughly flushed, the flow was stopped and the column pre-filled with potassium reattached. The potassium ions were then eluted and collected in a 25-ml graduated cylinder. The concentration of potassium ions was determined by quantitative cation chromatography, using a Dionex ICS-2000 system equipped with a CS16 analytical column and a CMMS III suppressor. The cation exchange capacity Λ (μmol/m2) can be then calculated through Eq. (1):

| (1) |

where NK+ is the amount of potassium ions eluted out of the column. The measured amount of potassium was corrected for the amount of free ions in the void volume of the column represented by CK+V0, where CK+ is the concentration of potassium ion in the eluent, V0 is the void volume measured by uracil. The term A represents the specific area of the silica particles (250 m2/g) and ω is the weight of the particles in a 5.0×0.46cm column, which is assumed to be 0.5 g.

2.7 Chromatographic Conditions

All chromatographic experiments were carried out on a Hewlett-Packard 1090 chromatography system, equipped with a binary pump, an autosampler, a temperature controller and a diode array detector (Hewlett Packard S.A., Wilmington, DE). Data were collected and processed using Hewlett Packard Chemstation software. The solutes were prepared in ca. 1 mM 24/76 MeCN/water solutions and the injection volume was 10 μL. Acetate buffer was prepared from ammonium acetate, adjusting to the required pH with acetic acid. Formate buffer was prepared from ammonium formate, adjusting to the required pH by adding formic acid. pH was measured before addition of organic solvent unless otherwise noted.

2.8 Characterization of the loading capacity

Overloading studies were performed on a 5.0 cm × 0.46 cm HC-COOH column and a 5.0 cm × 0.46 cm Ace C18 column. Both columns were unused. Column efficiency (i.e. plate count) was measured at a series of different amounts of sample between 0.05 to 10 ug. The columns were thermostated at 40 °C and detection was at 210 nm. The mobile phases were 5 mM ammonium acetate (SW pH = 6.08, SS pH = 6.14 [63]) in 10/90 ACN/water (v/v) for the Ace C18 column and 5 mM ammonium acetate (SW pH = 5. 96, SS pH = 6.13 [63]) in 40/60 ACN/water (v/v) for the HC-COOH column. These mobile phases gave a similar range of retention factors for the basic solutes on both phases. Note that in this study, buffers were prepared and adjusted to the desired pH after addition of organic solvent (SwpH values), where the meter was calibrated in aqueous buffers. The measured pHs were then corrected by the appropriate δ parameter to convert pH scales from SW pH to SS pH by eliminating the differences in residual liquid junction potential of the electrodes between the aqueous calibration buffer and the target solutions [63].

2.9 Characterization of column stability

Dynamic stability tests were performed on an unused 5.0 cm × 0.21 cm HC-COOH column. A 24/76(v/v) ACN/water with 5 mM ammonium acetate (pH=5.0) mobile phase was first passed through the column at 60 °C for approximately 1.2 thousand column volumes, wherein the retentions of a neutral compound and a basic probe were recorded over time. The eluent was then switched to 24/76(v/v) ACN/water with 10 mM ammonium acetate (pH=6.0) to further test the stability of the HC-COOH phase. The same procedure was repeated.

3. Result and Discussion

3.1 Elemental analysis

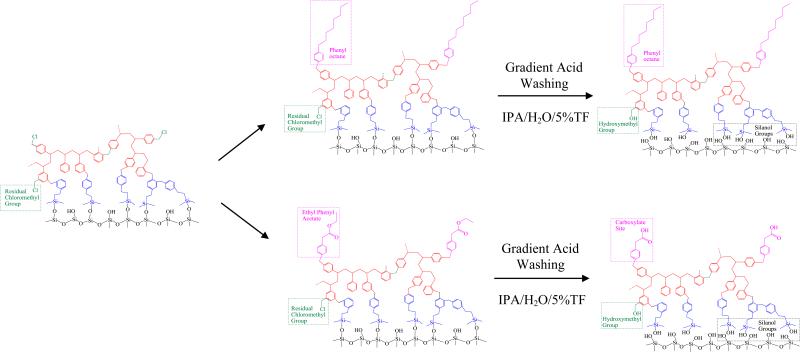

The synthesis scheme from the previous described HC-platform to the final HC-COOH phase and the phase structure at each step are shown in Figure 1. The product at each stage in the preparation was characterized by elemental analysis (see Table 2).

Figure 1.

Synthesis scheme for the HC-COOH and HC-C8 phases.

Table 2.

Summary of Elemental Analysis at Each Step in the Synthesis of the HC-COOH and the HC-C8 Phases

| Elemental analysis (wt/wt) | Surface coverage (mmol/m2) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase designation | %Ca | %Clb | Chloromethyl groupc | Octyl groupd | Carboxylic groupe |

| HC-platformf | 10.95 | 2.23 | 2.9 | N/A | N/A |

| HC-COOC2H5 | 12.54 | 0.89 | 1.2 | N/A | 0.5 |

| HC-COOH | 12.29 | <0.25 | <0.3 | N/A | 0.5 |

| HC-platformf | 11.00 | 2.09 | 2.8 | N/A | N/A |

| HC-C8 | 14.43 | 0.71 | 1.0 | 1.0 | N/A |

| HC-C8 after acid washing | 14.84 | 0.26 | 0.4 | 1.1 | N/A |

Detection limit is 0.10% (wt/wt).

Detection limit is 0.25% (wt/wt).

Surface coverage of chloromethyl groups based on chlorine analysis.

Surface coverage of octyl groups based on carbon analysis.

Surface coverage of carboxyl groups based on carbon analysis.

As shown in Figure 1, the HC platform has an extensive aromatic network completely confined to the particle's surface; the network was formed by a multi-layer, two-dimensional, orthogonal polymerization method using Friedel-Crafts chemistry [53,54] The resulting monolayer surface polymer shows dramatically enhanced acid stability and can be used at quite high temperatures [53,54,64].

In the development of the cation exchange HC-COOH phase, we decided to choose the Friedel-Crafts alkylation as our synthetic method after careful study of many derivatization reactions and in view of our experiences with Friedel-Crafts chemistry [53-56]. Specifically, a 10-fold molar excess of ethyl phenyl acetate, relative to amount of initial surface chloromethylphenyl groups, was used to introduce the cation exchange sites. During control reactions (data not shown) carried out in solution where benzyl chloride was used instead of complex silica matrix but otherwise under identical conditions, different reactivity was observed for ethyl phenyl acetate when compared to 1-phenyloctane. This result is not surprising and can be explained by the well known “substituent effect”[65]. In particular, the electron-donating octyl chains facilitated the reaction by increasing the electron density and thus activated the aromatic rings of phenyl octane; whereas the electron-withdrawing acetate groups inhibited the reaction by decreasing the electron density and thus deactivated the aromatic rings of ethyl phenyl acetate. As a result, after an hour of reaction with the surface chloromethyl groups at 80 °C, only 0.5 ± 0.1 μmol/m2 of phenyl acetate groups were attached to the aromatic network based on carbon content analysis, which is 50% less than the loading density of the phenyl octyl groups. After the synthesis was complete, the HC-COOH phase was extensively pre-treated by “gradient” washing at pH 0.5 and 150 °C. The purpose of this aggressive gradient acid washing is to: 1) introduce ion exchange sites by hydrolyzing the acetate into the corresponding carboxylic acid, 2) remove tin contamination introduced during the Friedel-Crafts reactions, 3) hydrolyze residual chloromethyl groups [66] and the labile Si-O-Si bonds to prevent their slow hydrolysis over time during use. We believe that almost all the labile bonds and groups will be broken or reacted after the aggressive acid treatment. For example, nearly all chlorine was removed from both phases as shown in Table 2, which suggests that the chloromethyl groups were almost completely hydrolyzed to hydroxylmethyl groups.

It is very important to note that based on the change in the carbon content of the HC-C8 phase there was essentially no loss in the amount of bonded phase as a result of this very aggressive acidic washing procedure. This confirms the existence of the hyper-crosslinked network on the particle surface. This also indicates that the 2% decrease in the carbon content of the HC-COOH phase is mainly due to the hydrolysis of the ester bond and the amount of carboxylate groups remains about 0.5 ± 0.1 μmol/m2, which is five times higher than that of sulfonyl groups on the –SO3-HC-C8 phase[30,49]. Previous work [30,49] in this lab demonstrated the strong cation exchange ability due to the presence of 0.1 μmol/m2 sulfonyl groups. Thus we believe the amount of carboxylate sites on the HC-COOH phase should provide a reasonable degree of weak acid cation exchange selectivity to the hydrophobic hyper-crosslinked substrate.

3.2 Characterization of the cation-exchange capacity at different pH

3.2.1 Ion chromatography

The ion exchange capacity was first assessed by ion chromatography as described in our previous publications [49]. Table 3 shows the ion exchange capacity for potassium on the HC-COOH and HC-C8 phases measured at three different pHs respectively. As can be seen, at pH = 4, the cation exchange capacity of the HC-COOH phase is only slightly higher than the HC-C8. This is because the carboxyl groups are weak acids with pKa ~ 5, suggesting only half of the groups should be ionized at pH 5 and less than 10% at pH 4. Therefore, at this pH (i.e. 4.0) when the ionization of carboxylic groups are greatly suppressed, the ion exchange sites found on the HC-COOH phase are mainly due to ionized surface silanol sites on silica and possibly from the organic silanol sites generated when siloxane bonds of the bonded phase are hydrolyzed during the hot acid aging step and thus would be about the same in number on the HC-COOH phase as on the related HC-C8 phase. However, as the pH is increased we see an increasingly more potassium ions on the HC-COOH column. At pH = 6 where almost all of the carboxylic acids are ionized (i.e. pH > pKa+1), more than twice as many cation exchange sites were measured on HC-COOH phase than on the HC-C8 material. Overall, the results here confirm the significant increase in cation exchange capacity on the HC-COOH phase due to the introduction of the carboxylic acid groups after acid treatment. The total amount of carboxylic acid groups, as measured under pH = 6, is roughly 0.54 μmol/m2. This agrees very well with the results based upon the elemental analysis as discussed above.

Table 3.

The Cation Exchange Capacity of the HC-COOH and HC-C8 Phases

| Stationary phases | Void volume (ml) | Total amount of K+ eluted from column (mmol) | Cation-exchange capacity (mmol/m2)a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH = 4.0 | pH = 5.0 | pH = 6.0 | pH = 4.0 | pH = 5.0 | pH = 6.0 | ||

| HC-COOHb,c | 0.608 | 58.96 | 77.95 | 130.95 | 0.42 | 0.57 | 1.00 |

| HC-C8b,d | 0.572 | 52.69 | 57.70 | 62.73 | 0.38 | 0.42 | 0.46 |

| [-COOH]=L(HC-COOH)-L(HC-C8)e | 6.27 | 20.25 | 68.21 | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.54 | |

| -SO3-HC-C8b,f | 0.476 | 11.99 | 0.11 | ||||

The cation exchange capacity was calculated based on Eq. (1) assuming that each column was packed with 0.5 g of particles.

Phase designation is the same as in Table 1.

For HC-COOH phase, Λ(HC – COOH) = Λ(–SiOH) + Λ(–COOH).

For HC-C8 phase, Λ(HC – C8) = Λ(–SiOH).

The number of ionized carboxylic groups on the HC-COOH at different pH.

The data was obtained from reference [49]. The cation exchange capacity of the -SO3-HC-C8 was measured in 50/50 ACN/water containing 0.1% formic acid (pH=2.8).

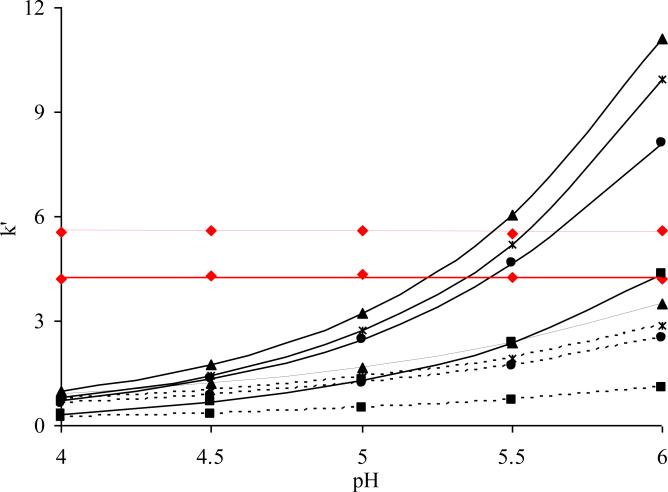

3.2.2 Effect of pH on the retention of basic compounds on HC-COOH phase

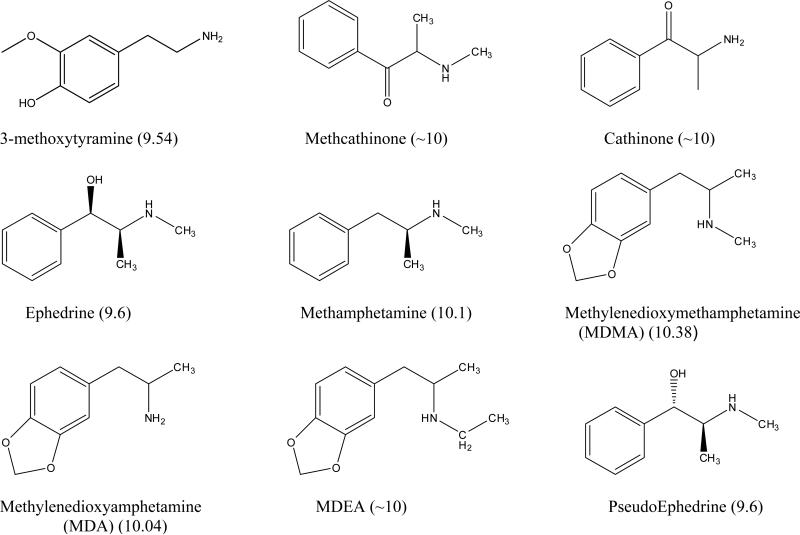

We next examined the cation exchange capacity of the HC-COOH phase by measuring the retention of basic solutes at different pHs. The probes used in this study were a number of highly hydrophilic basic compounds including catecholamines and amphetamine related drugs (see Figure 2 for the compounds structure). Figure 3 shows the retention changes of the test solutes as a function of the pH. As expected, all the basic solutes become substantially more retained as the pH is increased while the retention of neutral compounds stays the same. If we compare the two HC phases, it is clear that the two curves essentially converge on the left side of the plot at pH = 4, suggesting the similar numbers of ion exchange sites as found in the ion exchange capacity study. As we move to higher pH where the carboxylic acid groups start to ionize, the two curves begin to separate where increasingly more retention of the basic compounds is obtained on the HC-COOH column. At pH = 6 where the carboxylic acids are mostly charged and significantly enhanced ionic retention should occur, retention has increased more than 10 fold relative to retention at pH 4.

Figure 2.

The structures and pKa values of the basic solutes used in the ion-exchange and overload studies.

Figure 3.

Plots of k’ vs. pH on the HC-COOH and HC-C8 phases. Chromatographic conditions: 24/76 ACN/water with 10mM NH4Ac at pH 4.0, 4.5, 5.0, 5.5 or 6.0 buffered by acetic acid. 5.0 cm × 0.46 cm column, T = 40 °C, F = 1.0 ml/min. Solutes: (◇) Acetophenone; (▲) Methcathinone; (*) Ephedrine; (•) Cathinone; (■) 3-methoxytyramine. The solid lines are the retentions measured on the HC-COOH phase; The dotted lines are the retentions measured on the HC-C8 phase.

Based on the retentions of basic solutes on HC-COOH phase and HC-C8 phase, the percent contributions of the –COOH groups to the total retention at different pH were estimated using the following equation:

| (2) |

where the ion exchange contribution from silanol groups can be estimated and calibrated based on the HC-C8 phase. As shown in Table 4, clearly the HC-COOH phase showed a mixed-mode retention mechanism with the presence of both cation exchange sites and hydrophobic interaction sites. When the pH is below 5.0, retention on HC-COOH is dominated by the hydrophobic hyper-crosslinked substrate; when the pH is above 5.0, the added carboxylate groups start to play a more important role in determining the overall retention of basic analytes. This suggests that the new HC-COOH phase can function as an ordinary RPLC phase for polar and non-polar non-electrolyte analytes. At the same time, polar cationic compounds which could not be separated on typical reversed phases due to very low retention are now much more retained and thus better separated on the new weak cation exchange phase. As a result, one of the most interesting features of this new material is that both neutral organic compounds and charged bases can be simultaneously separated on the same phase under the same conditions, that gradients in either organic modifier, pH or ionic competitors can be used to affect the separation of a wide range of solutes and in contradistinction to what is usually observed on traditional RPC media charged organic bases are more retained than are related but uncharged solutes. This will be discussed in more detail below.

Table 4.

The Total Retention and Percent Cation Exchange Contributions on the HC-COOH Phase as a Function of pHa

| pH | Stationary phase | Retention | Acetophenone | 3-methoxy tyramine | Solutes Methcathinone | Cathinone | Ephedrine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.0 | HC-COOH | k′total=k'RP+k'IEX,[SiOH]+k'IEX,[COOH] | 4.21 | 0.33 | 0.97 | 0.73 | 0.82 |

| HC-C8 | k′total=k'RP+k'IEX,[SiOH] | 5.57 | 0.22 | 0.90 | 0.65 | 0.74 | |

| %k ′ IEX,[COOH] b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 4.5 | HC-COOH | k′total=k′RP+k'IEX,[SiOH]+k'IEX,[COOH] | 4.30 | 0.68 | 1.74 | 1.33 | 1.45 |

| HC-C8 | k′total=k'RP+k'IEX,[SiOH] | 5.59 | 0.34 | 1.21 | 0.87 | 1.00 | |

| %k ′ IEX,[COOH] b | 35 | 27 | 29 | 26 | |||

| 5.0 | HC-COOH | k′total=k'RP+k'IEX,[SiOH]+k'IEX,[COOH] | 4.32 | 1.31 | 3.22 | 2.48 | 2.73 |

| HC-C8 | k′total=k'RP+k'IEX,[SiOH] | 5.61 | 0.50 | 1.67 | 1.22 | 1.38 | |

| %k ′ IEX,[COOH] b | 53 | 46 | 48 | 47 | |||

| 5.5 | HC-COOH | k′total=k'RP+k'IEX,[SiOH]+k'IEX,[COOH] | 4.26 | 2.38 | 6.04 | 4.64 | 5.20 |

| HC-C8 | k′total=k'RP+k'IEX,[SiOH] | 5.51 | 0.73 | 2.36 | 1.70 | 1.94 | |

| %k ′ IEX,[COOH] b | 65 | 60 | 62 | 61 | |||

| 6.0 | HC-COOH | k′total=k'RP+k'IEX,[SiOH]+k'IEX,[COOH] | 4.23 | 4.35 | 11.10 | 8.11 | 9.93 |

| HC-C8 | k′total=k'RP+k'IEX,[SiOH] | 5.59 | 1.06 | 3.51 | 2.50 | 2.85 | |

| %k ′ IEX,[COOH] b | 73 | 68 | 68 | 71 |

It is also noteworthy that the chemical nature of the carboxyl groups does not seem to be strongly affected by their being a part of surface-bound monolayer structure. Based on the combined pH profiles of two independent experiments: 1) frontal analysis of ion exchange capacity using small inorganic probes (i.e. potassium acetate)(see Table 3); and 2) the retention studies of basic drugs at various pHs (see Figure 3), we can estimate the dissociation constant of the bonded acid groups. In the 24/76 (v/v) ACN/water mixture, the pKa value of the surface carboxyl groups is approximately 5.3. Interestingly, this is in good agreement with the reported pKa value for free phenyl acetic acids in 24/76 ACN/water [67], suggesting the solvation environment around these surface-anchored carboxylic groups is not significantly different from the free acid dissolved in bulk mobile phase. A possible explanation is that the carboxylic acid groups introduced during the last step of phase synthesis are primarily attached to the surface of the hyper-crosslinked network rather than deeply embedded within the stationary phase.

3.3 Hydrophobicity of the HC-COOH phase

To better understand the overall retention of the HC-COOH phase, we also evaluated the hydrophobicity of the HC-COOH phases based on the free energy of transfer per methylene group from the stationary phase to the mobile phase. A series of alkylphenone homologs were tested on the HC-COOH phase, HC-C8 phase, -SO3-HC-C8 phase and a commercial ODS phase (i.e. SB-C18). The free energy can be estimated via the Martin equation:

| (3) |

Where linear regression analysis of log k’ versus nCH2 allows the free energy to be calculated from the slope, B from the equation:

| (4) |

The slopes, intercepts and free energies of transfer per methylene group for the various phases together with the correlation coefficients and standard errors of the regression are listed in Table 5. We see from the result that the hydrophobicity (represented by ΔG°CH2) follows the order: HC-COOH < -SO3-HC-C8 < HC-C8 < SB C18. As expected, the new HC-COOH phase shows the lowest hydrophobicity; the lower free energy of transfer compared to the other two HC phases is mainly due to the absence of the hydrophobic octyl chain. The HC phase's hydrophobicity decreases upon introduction of polar sulfonyl groups but it is only a very small change as clearly indicated by less than 10% decrease in the ΔG°CH2 of -SO3-HC-C8 when compared to HC-C8. The lower hydrophobicity of the HC-C8 phases compared to the commercial C18 phases results from a combined effect of shorter alkyl chain (i.e. C8 vs. C18) as well as a lower surface ligand density (i.e. 0.9 μmol/m2 vs. 2-3 μmol/m2). Nevertheless, it is important to note that the hydrophobic hyper-crosslinked platform ensure that the ΔG°CH2 of the HC-COOH phase to be still about 65% of that of SB C18 and 81% of that of HC-C8. As will be discussed in more detail below, the hydrophobicity of the HC-COOH phase is very important for the separation of hydrophilic cations.

Table 5.

The Slopes and intercepts of logk' vs. nCH2, and ΔG°CH2 Obtained on Different Stationary Phases

| Stationary phases | Slopea | Interceptb | R2c | S.E.d | ΔG°CH2e(cal.mol-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SB C18f | 0.226 ±0.0006 | -0.073 ±0.003 | 0.999985 | 0.0019 | -324 ±0.9 |

| HC-C8f | 0.195 ±0.0006 | 0.100 ±0.003 | 0.999980 | 0.0014 | -280 ±0.9 |

| -SO3-HC-C8g | 0.183 ±0.0002 | -0.033 ±0.001 | 0.999997 | 0.0007 | -262 ±0.3 |

| HC-COOHf | 0.147 ±0.0004 | -0.003 ±0.002 | 0.999979 | 0.0012 | -210 ±0.6 |

The slope of the linear regression of log k' vs. nCH2 based on the data in Fig. 4

The intercept of the linear regression of log k' vs. nCH2 based on the data in Fig. 4

The squared correlation coefficient of the linear regression of log k' vs. nCH2 based on the data in Fig. 4

The standard error of the linear regression of the linear regression of log k' vs. nCH2 based on the data in Fig. 4

The free energy of transfer per methylene group calculated from Eq. (4) using the corresponding slope given in Table 4.

Chromatographic conditions: 50/50 MeCN/H2O with 0.1% formic, 5.0 cm × 0.46 cm column, T = 40 °C, F = 1.0 ml/min. Alkylphenone homolog solutes: acetophenone, propiophenone, butyrophenone, valerophenone, hexanophenone.

The data is obtained from reference [49]. Chromatographic conditions: 50/50 MeCN/H2O with 0.1% formic acid and 10mM TEA.HCl, 5.0 cm × 0.46 cm column, T = 40 °C, F = 1.0 ml/min.

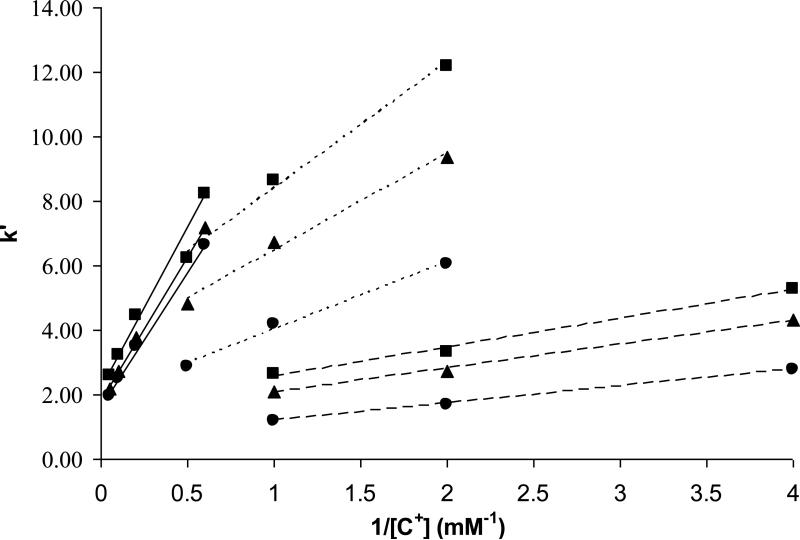

3.4 Retention mechanism on HC-COOH phase

Ion-exchange theory indicates that the ion-exchange contributions to k’ must decrease as the eluent concentration of counterion is increased. Specifically, according to the stoichiometric displacement model involving both reversed phase and ion exchange mechanism [68], the total retention factor of a singly charged basic compounds on a hydrophobic ion-exchange phase using a singly charged displacer is given by the following equation, where [C+] is the displacer concentration in the mobile phase:

| (5) |

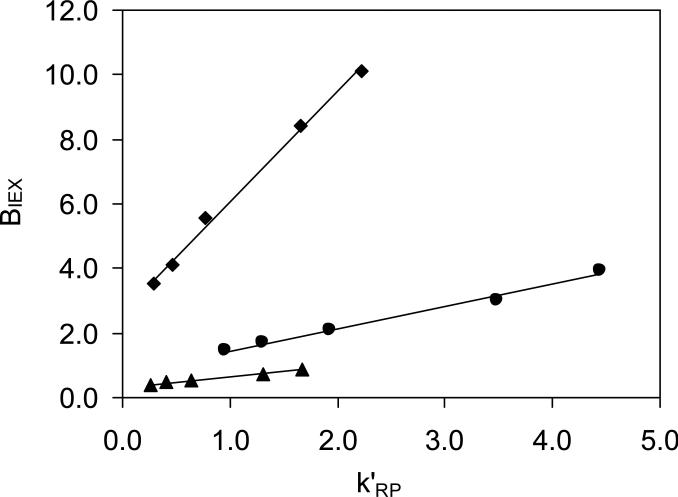

The intercept of a plot of k' versus1/[C+]m, k'RP represents an “ion-exchange-free” contribution to retention since it corresponds to the k' at infinite displacer concentration. The slope BIEX is a measure of the strength of the ion-exchange interaction process; it is proportional to the ion-exchange equilibrium constant and to the number of negatively charged sites on the stationary phase surface. Figure 4 illustrates the dependence of the retention factors of three singly charged analytes on HC-COOH phase as a function of different monoamine displacers. As can be seen, very good linear relationships were observed between k’ and the reciprocal of the displacer concentration where the protonated ammonium (NH4+), n-butylamine (n-BuNH3+) and n-octylamine (n-OctNH3+) were used as the displacers. The slopes BIEX and the intercepts k'RP of the regression are listed in Table 6a. The reversed-phase and ion exchange contributions to the total retention at different displacer concentrations (see Table 6b) can be further separated using Eq. (5) by applying the BIEX and k'RP from Table 6a.

Figure 4.

Plots of k’ vs. 1/[C+] on the HC-COOH phase. Chromatographic conditions: 24/76 ACN/water with different amount of cationic displacer buffered by acetic acid (pH=5.0). 5.0 cm × 0.46 cm column, T = 40 °C, F = 1.0 ml/min. Cationic solutes: (■) Methcathinone; (▲) Ephedrine; (•) Cathinone. a. Solid lines displacer is NH4+. b. Dotted lines (....) displacer is n-BuNH3+. c. Dashed lines (----) displacer is n-OctNH3+.

Table 6a.

The Slopes and Intercepts of k' vs. 1/[C+] Obtained on the HC-COOH Phase with Different Cationic Displacers

Table 6b.

The Total Retention and the Percent Cation Exchange Contribution on the HC-COOH Phase as a Function of Cationic Displacera

| Solutes |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Displacer | [C+] (mM) | Retention | Acetophenone | Cathinone | Methcathinone | Ephedrine |

| ammonium | 10 | k ′ total | 4.32 | 1.31 | 3.22 | 2.48 |

| %k ′ IEX b | 0 | 42 | 31 | 34 | ||

| 5 | k ′ total | 4.36 | 1.96 | 4.44 | 3.49 | |

| %k ′ IEX b | 0 | 59 | 48 | 50 | ||

| 1.67 | k ′ total | 4.41 | 4.09 | 8.24 | 6.65 | |

| %k ′ IEX b | 0 | 81 | 73 | 75 | ||

| n-butylamine | 2 | k ′ total | 4.32 | 2.87 | 6.21 | 4.80 |

| %k ′ IEX b | 0 | 35 | 31 | 30 | ||

| 1 | k ′ total | 4.33 | 4.17 | 8.64 | 6.74 | |

| %k ′ IEX b | 0 | 52 | 47 | 46 | ||

| 0.5 | k ′ total | 4.32 | 6.05 | 12.17 | 9.37 | |

| %k ′ IEX b | 0 | 68 | 64 | 63 | ||

| n-octylamine | 1 | k ′ total | 4.16 | 1.20 | 2.62 | 2.11 |

| %k ′ IEX b | 0 | 45 | 35 | 36 | ||

| 0.5 | k ′ total | 4.16 | 1.66 | 3.34 | 2.71 | |

| %k ′ IEX b | 0 | 62 | 52 | 53 | ||

| 0.25 | k ′ total | 4.21 | 2.79 | 5.26 | 4.32 | |

| %k′IEXb | 0 | 77 | 68 | 69 | ||

First, it is quite clear that finite intercepts were obtained in all three cases. The finite intercepts unambiguously validated the existence of the hydrophobic interaction mechanism on HC-COOH phase, resulting in retention under conditions where retention by ion-exchange has been eliminated [69].

Secondly, we see from the slopes that changing the cationic modifiers has a significant impact on the magnitude of the ion exchange interaction (represented by BIEX). Specifically, it follows the order: BIEX (NH4+) > BIEX (n-BuNH3+) > BIEX (n-OctNH3+), suggesting the ion exchange retention of basic analytes can be suppressed as the length of the alkyl chain on the amine displacers is increased that is as the displacer becomes more hydrophobic. The same trend was reported previously where the effects of various amine mobile phase modifiers were investigated as silanol blocking agents [68,70-72]. Amine modifiers that have higher hydrophobicity but little increases in steric hinderance [68,70] are found to be more effective in reducing peak tailing and controlling the retention of basic analytes. As pointed out by Nahum and Horvath, and Bij et al. [68,70-72], this results from enhanced binding of these more hydrophobic displacers. Consequently they act as better competitors for surface silanol groups and thus at a given concentration, give lower retention of basic analytes. This was also confirmed by a study in this laboratory on PBD-ZrO2 [73] a completely different reversed phase where dynamically adsorbed phosphate ions act as the ion exchange sites.

In general, it is clear that the choice of the amine modifier is critical in determining the ion-exchange contribution to the overall retention on HC-COOH phase. For the purpose of this study, most of the work was done using ammonium ion as the amine modifier, mainly because of its high volatility and considerable cation exchange ability at low concentration, which makes the mobile phase more LC-MS compatible. In addition, as will be discussed in detail later on, ammonium ion also provided very good peak shape for the basic compounds studied.

Similar to what we reported previously on silica based Alltima ODS, PBD-ZrO2 phase [73] and -SO3-HC-C8 phase [49], a good linear relationship is observed between the two parameters k'RP and BIEX with finite intercepts (see Figure 5). This indicated the presence of an interesting type of ion exchange sites, which we previously termed “hydrophobic assisted ion exchange sites” [73], in addition to the pure ion exchange interaction site. As we know, for equally charged solutes, the increase in “pure” ion-exchange retention can not improve selectivity [69,73], but only contributes to the overall retention. However, the existence of the hydrophobic assisted ion exchange sites facilitates the separation of analytes with similar charge to size ratios provided that they have different hydrophobicitites. As a result, hydrophobic interactions superimposed on ion exchange become one of the key factors to provide high and adjustable selectivity for different basic compounds on the HC-COOH phase.

Figure 5.

Plots of BIEX vs. k'RP on the HC-COOH phase with different cationic displacers. Chromatographic conditions are the same as Figure 4. The solid lines in each plot are the least square fittings of the corresponding data. (■) [NH4+], R2 = 0.995; slope = 3.4±0.1; S.D. = 0.2; (•) [n-BuNH3+], R2 = 0.991; slope = 0.68±0.04; S.D. = 0.1; (▲) [n-OctNH3+], R2 = 0.997; slope = 0.33±0.01; S.D. = 0.1.

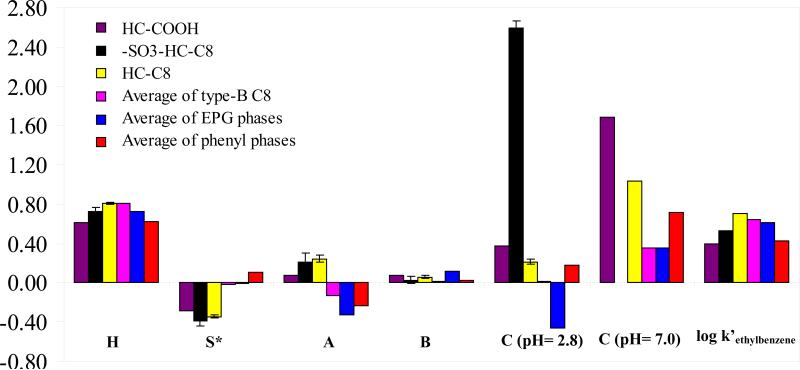

3.5 Comparison of HC-COOH phases and other RPLC phases by Snyder-Dolan Hydrophobic Subtraction Method

To more completely investigate the selectivity of the HC-COOH phase, the comprehensive hydrophobic subtraction method (HSM) developed by Snyder and his collaborators [18-22,32,74-76] was used to characterize and compare it with a few related stationary phases for differences in their selectivities. In the HSM approach, a set of 16 very judiciously selected but chemically simple probe solutes are used to study the stationary phases with a set of 5 phase parameters by fitting relative retention data of the 16 probe solutes to the equation [32]:

| (6) |

Here, ethylbenzene is a “neutral” reference compound. The five phase coefficients represent the five dominant solute-column interactions as elucidated and explained by the Snyder group; specifically they are: hydrophobicity (H), steric resistance (S*), hydrogen-bond acidity (A), hydrogen-bond basicity (B), and cation-exchange activity (C). The first four stationary phase parameters have been shown to be relatively independent of the mobile phase [32], although the C-term is very pH dependent and C is available at two pHs (2.8 and 7.0) [32]. This approach has been explored extensively [18-22,32,74-76] and found very useful in the classification of more than 400 reversed phases of different types.

The new HC-COOH phase was studied by this method to compare it with the reversed phase HC-C8 and the strong cation exchange phase –SO3-HC-C8 derivatized from the same hyper-crosslinked platform. The resulting column parameters together with the average data of a few related commercials phases are listed and compared in Figure 6. As indicated by the regression results (see the caption of Figure 6), all of the HC-based phases showed excellent fittings using the HSM. The squared correlation coefficients are very close to one and the corresponding standard errors are quite small.

Figure 6.

The column selectivity parameters of different phases measured by Snyder-Dolan HSM method. Chromatographic conditions: 50/50 ACN/60mM phosphate buffer (pH = 2.8 or 7.0), T = 35 °C, F = 1.0 ml/min. The squared correlation coefficients and the standard errors of the regression of Eq. 6 indicate good fits for all three phases: HC-COOH, R2 = 0.994, S.E. = 0.034 ; HC-C8, R2 = 0.999, S.E. = 0.022; –SO3-HC-C8, R2 = 0.995, S.E. = 0.060; The data for HC-C8, –SO3-HC-C8, type-B C8 phases, EPG phases and phenyl phases were obtained from reference [49].

We see from the results in Figure 6, the hydrophobicity (represented by H) follows the order: HC-COOH ~ Phenyl < EPG ~ –SO3-HC-C8 < HC-C8 ~ type-B C8, which agrees very well with the order of hydrophobicity measured by the alkylphenone homolog solutes (see section 3.3). As expected, the H value of the HC-C8 phase is almost the same as the average of 38 type-B silica-based commercial C8 phases, both of which showed the highest hydrophobicity among all the phases compared. The hydrophobicity of –SO3-HC-C8 is reduced upon introduction of polar sulfonyl groups as previously reported [49]. A bigger decrease as compared to the –SO3-HC-C8 in H is observed with the HC-COOH phase, which exhibits a hydrophobicity close to the average value of the phenyl phases. This can be attributed to the absence of the hydrophobic octyl chain on the HC-COOH phase as discussed above.

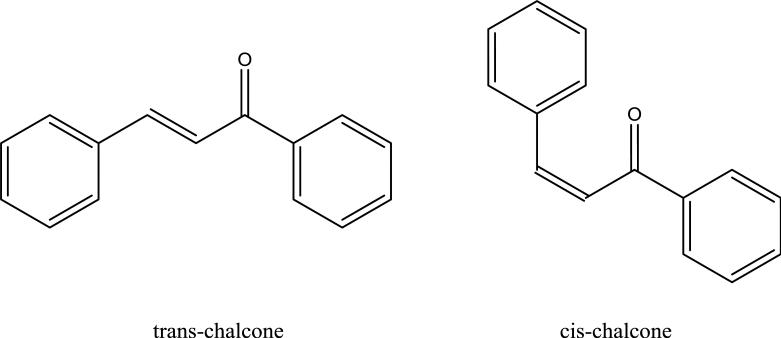

The S* coefficients, are clearly negative and larger in magnitude for all the HC-phases compared to the three general classes of conventional phases given in the figure. This means that the steric repulsion contribution to selectivity is actually retention enhancing on these materials. All HSM coefficients other than the H coefficient are best understood as phase properties relative to a “typical” type-B alkyl silica phase. Thus if a phase has a parameter of zero it means that it behaves in this regard just as does the “typical” phase. Consequently a phase with a negative S* means that a solute with a correspondingly larger σ value (steric impedance) will be more retained on the phase in question as compared to a “typical” phase. In fact, when we compared the S* values for over 400 reversed phases (data not shown here) derivatized with a wide variety of surface chemistries (e.g. cyano, phenyl, fluoro, EPG), the HC phases showed the most negative value of all phases reported by Snyder [77], suggesting that the two solutes (i.e. trans-chalcone and cis-chalcone), which are major determinants of S*, are much more strongly retained on the HC phases than on conventional RPLC phases. One potential cause of high retention of solutes with large σ values on HC phases is the rather low surface density of C8 groups (1.0±0.1 μmole/m2) or the ethyl phenyl acetic groups (0.5±0.1 μmole/m2) when compared to the typical 2.0 to 3.5 μmole/m2 of conventional alkylsilica phases. In addition, we also noticed that the two σ marker compounds are highly aromatic (see Figure 7). From the phase structures shown in Figure 1, we can see that our HC phases are also highly aromatic. Therefore, it is possible that strong π - π interactions might also contribute significantly to the strong retention of the two solutes and consequently lead to an apparent highly negative S*. Snyder and coworkers have previously pointed out the importance of such interactions especially with phenyl and cyano phases [20,21] and introduced an additional solute and phase parameter to deal with them. In the absence of such parameters we believe that π interactions “show up” in the S* parameter.

Figure 7.

The structures of the two marker compounds to determine S* in Snyder-Dolan HSM method.

The A values, which represent the stationary phase H-bond acidity, are higher for all the HC phases as compared to the averages of the other types of reversed phases (see Figure 6) and are among the top 10% of all the RPLC columns studied . This is mainly due to the large number of active hydrogen bond donors released upon hydrolyzing the siloxane bonds and hydrolysis of the chloromethyl groups on the surface of the HC platform upon post-synthesis hot acid washing. A further increase in A was expected on HC-COOH upon the introduction of the carboxylic acid groups. However, this change was not observed in this study, suggesting the small amount of the weak acid groups do not contribute significantly to the H-bond acidity of the HC-COOH phase.

The B terms, which represent the H-bond basicity of stationary phase, are lower on the HC phases than the average of the polar-embedded phases, but higher than the other commercial reversed phases listed in Figure 6. Comparing the B value of the three HC phases, the hydrogen-bond basicity of HC-COOH is similar to that of the –SO3-HC-C8 and essentially the same as that of HC-C8. According to Snyder, the B coefficient is postulated to be closely related to adsorbed water on the stationary phase [32]. This suggests that the amount of water adsorbed on the HC phases may be mainly controlled by the surface silanol groups and probably the benzyl alcohol groups from the hyper-crosslinked platform while the effect of the ion exchange groups (i.e. sulfonyl, carboxylate) is negligible.

As expected, radically different cation exchange interactions (represented by the C term) were observed for the HC phases derivatized with different functionalities. In particular, at pH of 2.8, an extraordinary C coefficient was measured for the strong cation exchange phase –SO3-HC-C8 (C –SO3-HC-C8 = 2.59), followed by the weak cation exchange phase HC-COOH (C HC-COOH = 0.378 ); while the C(2.8) coefficient of the HC-C8 phase (C HC-C8 = 0.215 ) is not very different from the average of all the commercial phenyl phase(C Phenyl = 0.181 ) [49]. As discussed above, the strong cation exchange ability of the –SO3-HC-C8 phase is mainly due to the presence of 0.11 μmole/m2 of sulfonate groups; while the ionization of carboxylic acid groups are greatly suppressed at pH 2.8, producing only a small value of C(2.8) for the HC-COOH phase. On the other hand, at pH 7.0, the cation exchange ability of the HC phases are greatly enhanced as indicated by its C(7.0) coefficient, particularly C HC-C8 = 1.032 on the reversed phase and C HC-COOH = 1.689 on the weak cation exchange phase. Compared to the average C8 phase, the HC-C8 phase has a much higher C (7.0) value. The finite positive C value of the HC-C8 phase indicates that it does have quite high cation exchange behavior at pH 7.0. We believe this is due to the large number of surface silanol groups released by the hot acid treatment. Further it should be noted that the HC phases are not endcapped because they are designed to be used in acid media. The presence of such deprotonated silanols along with the rather high surface density of carboxylate groups leads to further increases in the C(7.0) value of the HC-COOH phase, which is critical for the separation of polar cationic compounds that can not be retained on typical reversed phases.

It is very important to point out that the relatively high population of the surface silanol groups of the HC platform does not compromise the separation efficiency of the HC phases for basic analytes. In fact, when we compared the performance of HC-C8 with several commercial ODS phases with the best plate counts for amines, it showed the highest plate counts for all three basic compounds [54]. This suggests that silanol groups inherent in the silica base of the HC phases do not generate deleterious secondary interactions, which are believed to be the main reason for the bad peak shape and poor plate counts specifically for cationic analytes. This is further confirmed by this study wherein a set of drug compounds were tested on the HC-COOH phase (see Section 3.7).

Overall, the unique phase coefficients S, A, B, C(2.8), and C(7.0) of the HC-COOH phase were indicative for significant differences in phase selectivity in the separation of a wide variety of analytes. In the next section, we will compare the selectivity of the HC-C8-Hi-Sn phase with several commercial columns in the separation of non-electrolytes and basic analytes.

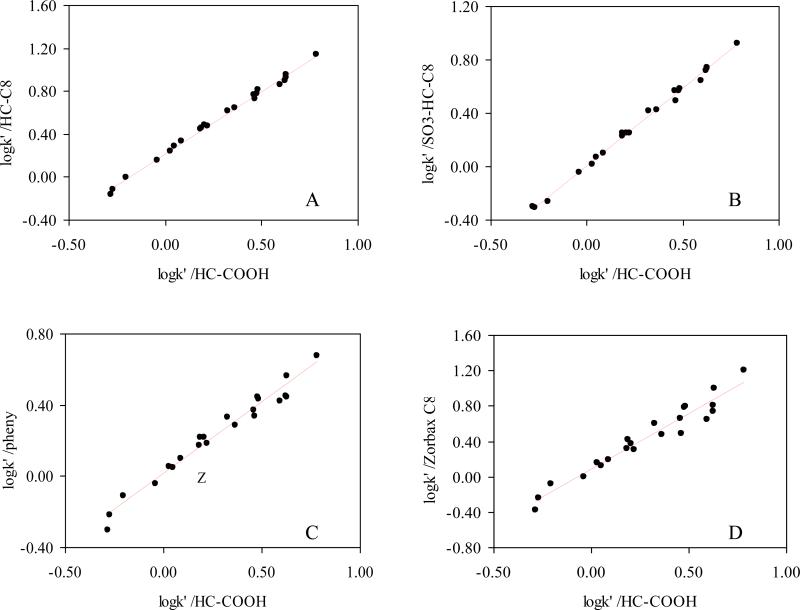

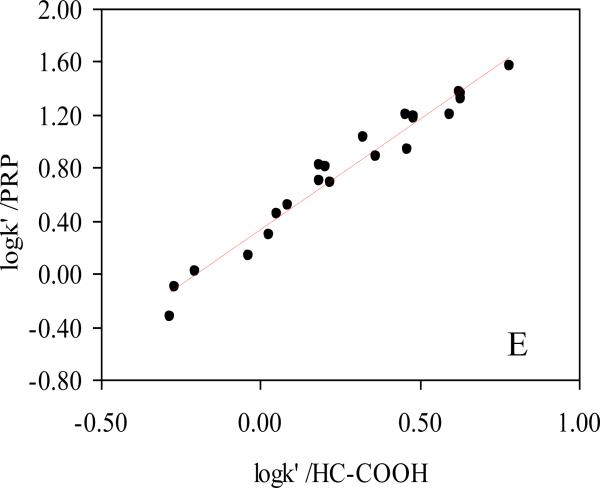

3.6 Selectivity comparison of the HC-COOH phase vs. other RPLC phases via κ−κ plot

3.6.1 Separation of non-electrolyte solutes

The difference in selectivity between two stationary phases can be summarized globally by a κ-κ plot [12]; this is a plot of log k’ of a judiciously selected set of solutes on one stationary phase versus the log k’ on a second phase. According to Horvath and coworkers [12], a good linear correlation between the two sets of log k’ indicates a similar retention mechanism on the columns compared; if the slope is close to 1.0 then the energetics are identical. On the other hand a poor linear correlation coefficient implies differences in retention mechanisms and selectivities.

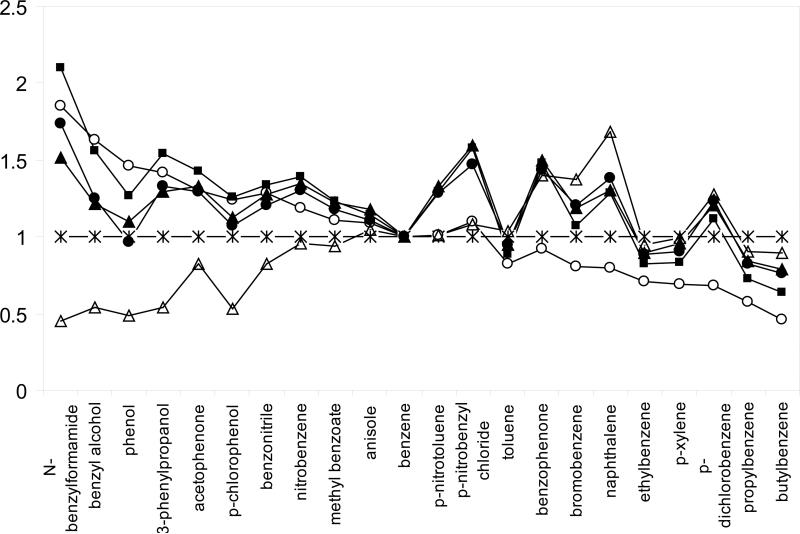

The HC-COOH phase was studied by twenty two non-electrolyte solutes commonly used in linear solvation energy relationship (LSER) studies of RPLC [14,61,78-80] and compared to a C8, phenyl, PRP, HC-C8 and –SO3-HC-C8 phases. The twenty-two solutes were selected to span a wide range in hydrophobicities, polarities and hydrogen bonding characteristics [78,79]. The κ-κ plots of the HC-COOH phase vs. the other four phases are shown in Figure 8. As expected, the HC-COOH shows very good correlations with the other two HC phases, which means that the three phases based upon the same hyper-crosslinked platform are very similar in the separation of these non-ionic solutes. For the three commercial phases, the HC-COOH phase exhibits the most different selectivity from the aliphatic phase Zorbax C8 and more closely resembles the two aromatic phases: phenyl phase and PRP. Moreover, the normalized k’ ratios (relative to the k’ of Zorbax C8) of all twenty two solutes on different phases were plotted to investigate the difference in selectivity towards each solute. As shown in Figure 9, the solutes were sorted from left to right in the ascending order of hydrophobicity according to their retentions on Zorbax C8. Therefore, we should expect a flat line at 1.00 for a phase that has very similar properties to the Zorbax C8. However, selectivities are clearly different among these phases as illustrated by the diverse retention patterns and many fluctuations. More importantly, the retention pattern of all twenty two solutes on the HC-COOH phase is almost identical to both of the other two HC phases. This indicated that the 0.5 μmol/m2 of surface carboxylate groups do not significantly change the surface non-ionic properties and the unique reversed phase selectivity of the hyper-crosslinked platform is preserved. This observation is consistent with previous result reported by Luo et. al [49].

Figure 8.

Selectivity comparison of various phases via log k’ vs. log k’ plots for the separation of the 22 LSER solutes. Chromatographic conditions: 50/50 ACN/water, T = 30 °C, F = 1.0ml/min. Data of –SO3-HC-C8 is obtained from reference [49]; Data of Zorbax C8, Phenyl and PRP phases are obtained from reference [73].

A HC-COOH vs. HC-C8 phase;

R2 = 0.995; slope = 1.17±0.02; S.D. = 0.03;

B. HC-COOH vs. –SO3-HC-C8 phase;

R2 = 0.996; slope = 1.16±0.02; S.D. = 0.02;

C. HC-COOH vs. Phenyl phase;

R2 = 0.969; slope = 0.80±0.03; S.D. = 0.05;

D. HC-COOH vs. Zorbax C8 phase;

R2 = 0.943; slope = 1.26±0.07; S.D. = 0.10;

E. HC-COOH vs. PRP phase;

R2 = 0.964; slope = 1.67±0.07; S.D. = 0.10;

Figure 9.

Selectivity comparison of different phases based on the retention of twenty two non-electrolyte LSER solutes via a plot of normalized k’ ratio. Chromatographic conditions are the same as Fig. 8. (*) Zorbax C8; (■) HC-COOH; (▲) HC-C8; (●) -SO3-HC-C8; (○) Phenyl; (∆) PRP.

To further assess and compare non-electrolyte selectivity of the HC-COOH phase, the retention of the twenty-two solutes on the new phase were fitted into the RPLC-LSER retention equation:

| (7) |

This equation allows the free energy of retention to be separated into several molecular interaction terms involved during the separation. Thus it has been used over two decades to study the physicochemical properties of stationary and mobile phases and assess the relative strength of the chemical interactions which contribute to differences in retention [78]. According to the definition of each parameter given by Kamlet and Taft [79,81], log k’0 is an independent term which relates to phase ratio. V2, π2*, Σα2H, Σβ2H, and R2 coefficients represent the “molecular volume [82], dipolarity/polarizability, hydrogen bond donor acidity, hydrogen bond acceptor basicity, and excess molar refraction behavior” of the solutes respectively. The multi-variable linear regression coefficients ν, s, a, b, and r refer to the chemical properties of the mobile and stationary phases that are complimentary to the solute descriptors. The definitions of the coefficients are listed below:

The rR2 term is a correction term that accounts for the inadequacy of lumping dipolarity and polarizability into a single term (sπ2 *). For a fixed mobile phase composition, these five coefficients of the chromatographic system can be used to quantitatively measure stationary phase selectivity; different interaction coefficients usually indicate different physicochemical properties of the phases.

The coefficients of the different stationary phases of interest are listed and compared in Table 7. It is clear that changes in surface chemistry have a profound effect on the intermolecular interactions and thus affect the selectivity of the HC-COOH phase. One of the major differences is seen in the ν-coefficient. When the carboxylic groups are introduced, the HC-COOH phase has a considerably decreased dispersiveness (smaller ν) than the reversed HC-C8 phase. This is undoubtly due to the absence of the hydrophobic octyl chain, thereby reducing the hydrophobic interaction between the solutes and the stationary phase. If we further compare the ν-values among different types of stationary phases, it follows the order: Phenyl < HC-COOH < HC-C8 < PRP < Zorbax C8, which agrees very well with the order of hydrophobicity measured by the homolog solutes and the HSM. Another significant difference is seen in the hydrogen bonding ability of the HC-COOH phase, as represented by changes in b-coefficients as compared to the HC-C8 phase. The enhanced hydrogen bonding basicity is not very surprising since the HC-COOH phase has both ionized carboxylate functionalities (i.e. 50/50 (v/v) ACN/water, pH~7.0) and more water sorption [32] on silica surface.

Table 7.

Comparison of LSER Coefficients on Different Stationary Phasesa

| Stationary phases | Column coefficients |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| log k'0 | v | s | a | b | r | SE | R2 | |

| HC-COOH | -0.47± 0.05 | 1.07 ± 0.06 | -0.11 ± 0.05 | -0.45 ± 0.05 | -1.24 ± 0.07 | 0.22 ± 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.989 |

| HC-C8b | -0.24 ± 0.06 | 1.21 ± 0.08 | -0.14 ± 0.06 | -0.54 ± 0.06 | -1.44 ± 0.08 | 0.19 ± 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.987 |

| -SO3-HC-C8b | -0.47 ± 0.05 | 1.22 ± 0.06 | -0.14 ± 0.04 | -0.55 ± 0.04 | -1.42 ± 0.06 | 0.20 ± 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.991 |

| Zorbax C8b | -0.25 ± 0.05 | 1.41 ± 0.06 | -0.27 ± 0.05 | -0.42 ± 0.05 | -1.61 ± 0.07 | 0.02 ± 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.993 |

| PRPb | 0.03 ± 0.07 | 1.35 ± 0.08 | -0.39 ± 0.06 | -0.94 ± 0.06 | -1.89 ± 0.08 | 0.48 ± 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.994 |

| Phenylb | -0.22 ± 0.06 | 0.83 ± 0.07 | -0.14 ± 0.05 | -0.34 ± 0.05 | -0.99 ± 0.07 | 0.09 ± 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.980 |

No significant changes were seen in the r-coefficient, which is consistent with previous HSM studies of hyper-crosslinked phases (see section 3.5). However, it is worthwhile pointing out that all of the HC phases (r = 0.19~0.22) showed rather high r-values, possibly indicating strong π - π interactions as compared to conventional aliphatic phases (Zorbax C8, r = 0.02) and even aromatic phases (phenyl, r = 0.09). These rather high r coefficients of our HC phases result from the hyper-crosslinked aromatic network, which appears to confirm our belief that π - π does play an important role in determining the selectivity of hyper-crosslinked phases.

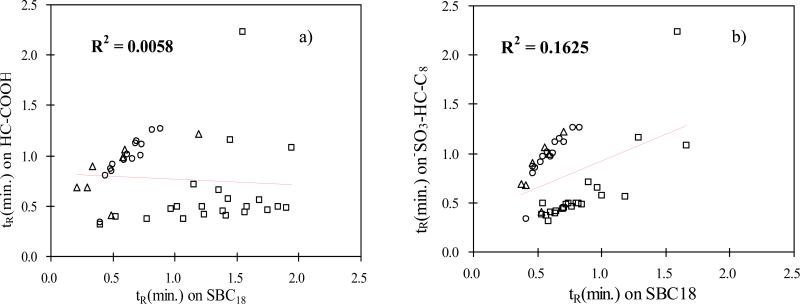

3.6.2 Separation of drugs of abuse

We noted in the HSM study above that the HC-COOH phase has a unique type of cation exchange behavior when compared to the other phases of interest. This suggests that the selectivity of the HC-COOH phase, especially for basic analytes, should be exceedingly different from the other RP phases, including the two HC phases based on the same platform.

A set of 43 basic drugs were chosen so that we could compare the selectivity of the HC-COOH phase with both –SO3-HC-C8 and a commercial ODS phase SB C18 (see Figure 10). These drugs can be divided into three chemical classes based upon their structures: phenethylamines, benzodiazepines and opiates. The compounds in each group share the same parent structure but are derivatized with different side groups. It should be pointed out that because of the fundamental differences in retention mechanisms, different eluent compositions must be applied under gradient elution conditions on the three phases to achieve comparable retention ranges. Specifically, an acetonitrile gradient from 10% to 56% and a salt (i.e. triethylamine) gradient from 0 to 50 mM in 2.50 min were used on SB-C18 and –SO3-HC-C8 phases, with acidic perchlorate solute used as the buffer for both gradient systems to increase retention times or loading capacities of some of the weakly retained cationic drugs through ion pair formation with the anion [83-85]. On the other hand, a pH gradient from 6.0 to 4.0 based on the use of acetate/formate was used with the HC-COOH phase. The normalized retention times obtained on the three separation systems are plotted in a manner similar to a κ − κ plot (see Figure 10). The scattered pattern of the data and close to zero correlations in both cases indicate the vastly different selectivities among the phases compared, and strongly suggest that the HC-COOH phase is a good candidate for “orthogonal” separations especially when cationic solutes are involved.

Figure 10.

Selectivity comparison of different phases via tR vs. tR plots based on the retention of the 43 regulated intoxicants. a) HC-COOH vs. HC-C8 phase; b) HC-COOH vs. –SO3-HC-C8 phase; Solutes: (○) Phenethylamine class; (□) Benzodiazepine class; (Δ) Opiate class.

Chromatographic conditions:

SB C18: eluent A: 20mM perchloric acid in water; eluent B: 20mM perchloric acid in 80/20 (v/v) ACN/water; gradient profile: 12.5-70% B in 0.00-2.50 min, 70-12.5% B in 2.50-2.51 min, and 12.5% B in 2.51-2.80min.

–SO3-HC-C8: eluent A: 20mM perchloric acid in 63/37 (v/v) ACN/water; eluent B: 20mM perchloric acid and 50mM triethylamine.HCl in 63/37 (v/v) ACN/water; gradient profile: 0-100% B in 0.00-2.50 min, 100-0% B in 2.50-2.51 min, and 0% B in 2.51-2.80 min;

HC-COOH: eluent A: 2mM ammonium acetate in 40/60 (v/v) ACN/water, pH = 5.5; eluent B: 2mM ammonium formate in 40/60 (v/v) ACN/water, pH = 4.0; gradient profile: 0-100% B in 0.00-2.50 min, 100-0% B in 2.50-2.51 min, and 0% B in 2.51-2.80 min;

Other chromatographic conditions: 5.0 cm × 0.21 cm column, T = 40 °C, F = 1.0 ml/min. wavelength =210 nm. Data of –SO3-HC-C8 and SB C18 are obtained from reference [30];

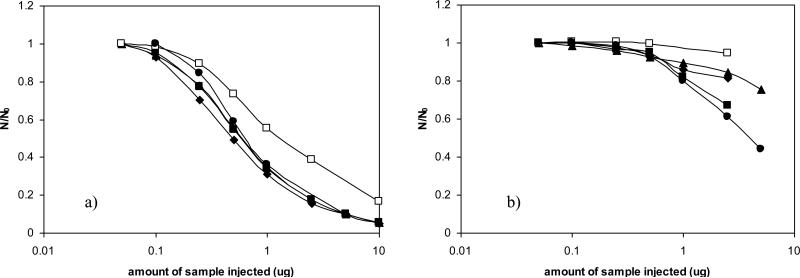

3.7 The loading capacity and limiting efficiency of bases on HC-COOH phase

The sample loading capacity of the HC-COOH phase was studied together with a commercial Ace C18 phase, which was selected for its high separation efficiency and loading capacity for basic analytes [86]. For both stationary phases, the plate counts of basic probes (N) were measured at a series of different sample loads (w) to generate an “overload profile” i.e. plot of N vs. w. The data (N, w) were then fitted to Eq. 8, which was developed by Dai and Carr [86] based on the kinetic Langmuir model of peak shape under overload conditions [87,88], to obtain the two key parameters: the limiting plate count (N0) and sample loading capacity (w0.5):

| (8) |

where ω’= w/ w0.5 is the normalized sample load.

Figure 11 shows the “overload profiles” for five basic drugs (structures are shown in Figure 2) on the HC-COOH and the ACE C18 phases using 60% ACN and 10% ACN as the eluent respectively. Due to the difference in strengths of the reversed-phase and ion-exchange interactions, the retentions for the five testing solutes on the two phases are radically different. On the ODS phases, there is essentially no retention of the basic compounds using polar solvent rich mobile phase. On the other hand, the amines are so strongly retained on the HC-COOH that a high percentage of ACN has to be used to ensure their elution within a reasonable time. To achieve similar retentions of the basic probes, we operated the columns at very different mobile phase conditions with substantially more acetonitrile used for the HC-COOH phase. As can be seen from Figure 11, both of the plots followed the same pattern with plate counts decreasing as the sample load was increased. However, it is evident that all of the five basic probes on the Ace C18 phase gave rather abruptly dropping plots; while the change of efficiency on the HC-COOH phase showed only moderate curvature suggesting much less tendency to overload.

Figure 11.

Comparison of sample loading capacity of Ace C18 vs. HC-COOH phase. Chromatographic conditions: a) Ace C18 column: 5mM ammonium acetate in 10/90 (v/v) ACN/water, pH = 6.08; b) HC-COOH column: 5mM ammonium acetate in 40/60 (v/v) ACN/water, pH = 5.96; Other chromatographic conditions: 5.0 cm × 0.46 cm column, T = 40 °C, F = 1.0ml/min. wavelength =210 nm. Solutes: (□) Methcathinone; (▲) MDA; (■) MDMA; (•) MDEA; (◇) Methamphetamine. The structures of the basic solutes are shown in Fig. 2. The retention factors are given in Table 8.

To quantitatively explore the overload behavior of the two phases, Table 8 shows the limiting efficiency N0, i.e. the efficiency under conditions of linear chromatography, and ω0.5 the sample loading capacity (the amount of sample (in nmol)) that can be injected which causes a decrease in efficiency by 50% from N0, and the limiting retention factor (defined as k’0) on both columns. As can be seen, both loading capacity and the limiting efficiency are found to be much better on HC-COOH compared to the ACE C18. In particular, the average column capacities on HC-COOH are more than an order of magnitude higher than that of the commercial ODS phase. This observation agrees with similar results reported by McCalley et al. [89] and can be attributed to the presence of additional retention sites (i.e. the ionized COOH sites) or to the neutralization of solute charge and reduction in mutual repulsion effects (note that the silica particles used for both columns have approximately the same surface area: 250 m2/g). In addition, very good column efficiency was obtained on the HC-COOH phase for all basic analytes using ammonium acetate buffer, with N0 in some cases almost 30% higher than for the ACE C18 phase. We believe that this results mainly from the open pore structure of the HC platform even after the extensive “orthogonal polymerization” and thus the phase maintains the fast mass transfer as previously described [52,54]. Note that these are 5 μm diameter particles and the column packing procedure has not been thoroughly optimized (Nacetophenone = 4100 for a 0.46 cm × 5.0 cm column), the separation efficiency of the HC-COOH phase in the low ionic strength buffer is clearly superior to the vast majority of classical ion exchangers based on organic polymer [90-92].

Table 8.

Effect of Column Type on Efficiency, Sample Loading Capacity, and Retention of Basic Drugs.

| HC-COOHb | Ace C18c | N0(HC-COOH) / N0(Ace C18) | w1/2(HC-COOH) / w1/2(Ace C18) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solutesa | k' | N0d | w1/2 (nmol)e | r2f | k' | N0d | w1/2 (nmol)e | r2f | ||

| Methamphetamine | 5.12 | 3680 | 77.4 | 0.885 | 3.90 | 2950 | 3.4 | 0.997 | 1.25 | 22.7 |

| MDMA | 5.58 | 3450 | 26.9 | 0.987 | 4.19 | 2980 | 3.0 | 1.000 | 1.16 | 9.1 |

| MDA | 4.21 | 3430 | 89.7 | 0.968 | 3.38 | 2960 | 3.0 | 0.999 | 1.16 | 30.2 |

| Methcathinone | 3.79 | 3490 | 190.0 | 0.978 | 2.21 | 2730 | 9.9 | 0.992 | 1.28 | 19.2 |

| MDEA | 6.56 | 3310 | 34.9 | 0.998 | 6.56 | 3110 | 5.0 | 1.000 | 1.06 | 7.0 |

Structures of the basic solutes are shown in Fig. 2.

The chromatographic conditions are the same as in Fig. 12.

The chromatographic conditions are the same as in Fig. 12.

The limiting plate count calculated from Eq. (7) using the corresponding data given in Fig. 12.

The sample loading capacity calculated from Eq. (7) using the corresponding data given in Fig. 12.

The squared correlation coefficient of the fits based on the data in Fig. 12.

It has been shown [93-95] that, due to the presence of detrimental ionic interactions, the separation of basic compounds on conventional RP columns frequently suffer from peak tailing and overloading. As discussed by McCalley peak shape and overload can deteriorate when low ionic strength buffers (e.g. formic acid) that are suitable for mass spectrometric detection are used [96]. However, even with the introduction of the carboxylate sites and the increase in the silanol population released from the post synthesis acid washing, the separation efficiency of basic analytes is not harmed. This suggests the amount of ionic sites/silanol is not the main cause of poor peak shape for basic analytes as previously reported by Bidlingmeyer [97]. We believe the application of the new HC-COOH phase, with the rather significantly improved loading capacity and limiting efficiency, can be fruitfully employed for the analysis of basic compounds including many pharmaceuticals and biomedical samples under conditions compatible with mass spectrometric detection.

3.8 Stability of HC-COOH phase

Previous studies [54-56] in this lab have adequately demonstrated the very high acid stability (i.e. at pH < 2) of the underlying HC platform even at elevated temperatures (>100 °C) thus this was not tested in the present work. However, the HC-COOH phase will likely find its greatest uses at higher pHs where the carboxylate group is partially ionized, thus the stability of the HC-COOH phase was further tested at two higher pHs (i.e. pH =5.0, and 6.0). In particular, we first flushed the column with 5 mM ammonium acetate (pH = 5.0) in 24/76 (v/v) ACN/water at 60 °C. After 1000 column volumes of mobile phase, there was essentially no change of retention for either the neutral or basic probes. The column was then subjected to a second stability test where the pH of the mobile phase was increased from 5.0 to 6.0. Note that 10 mM of ammonium acetate instead of 5 mM but otherwise identical conditions were used to ensure the reasonable retention of the basic compound at the higher pH. The changes in pH and ionic strength did not affect the stability of the HC-COOH phase. The plots (not shown here) of % k’ versus column volume for the two testing probes showed almost no loss in retention and confirmed the stability of the hyper-crosslinked phases even under the higher pH conditions.

4.0 Conclusions

A novel type of silica-based carboxylate modified reversed phase HC-COOH has been synthesized by introducing a small amount of carboxylate functionality into an aromatic hyper-crosslinked (HC) networks of a previously developed acid stable materials. We concluded that:

Based upon the free energy of transfer per methylene unit, ΔG°CH2, the H coefficient of the Snyder-Dolan HSM characterization method, and ν coefficient of the LSER approach to understanding retention mechanisms, it is clear that the hydrophobicity of HC-COOH is reduced compared to other hyper-crosslinked phases mainly due to the absence of the hydrophobic octyl chain. However, ~80% of the hydrophobicity of the original HC-C8 phase is preserved on the new HC-COOH phase.

Based upon the C coefficient observed in our study of the Snyder-Dolan HSM characterization method at pH 2.8 and pH 7.0, and the inverse correlation between the retention of basic probes and the eluent concentration of counter ion, it is clear that the HC-COOH phase acts as a hydrophobically assisted weak cation exchanger, wherein the strength of the cation exchange interaction between cationic solutes and HC-COOH phase is largely controlled by the intensity of the hydrophobic interaction between the solutes and the stationary phase.

The phase thus prepared showed a mixed-mode reversed-phase/weak cation exchange (RP/WCX) retention mechanism, which clearly distinguishes the carboxylic phase from conventional reversed phases.

The novel retention mechanism provides the HC-COOH phase with a very different selectivity allowing the facile separation of both highly hydrophilic basic compounds and neutral solutes.

Excellent efficiency and enhanced sample loading capacity for basic compounds were also demonstrated in the successful application of the HC-COOH phase to the separation of drugs of abuse.

Selectivity can be tuned by varying the concentration of weak acid buffers such as formate and acetate systems which are very compatible with mass spectrometric detection.

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Institutes of Health for financial support. We also thank Agilent Technologies Inc. (Wilmington, DE, USA) for the donation of Zorbax silica and Mac-Mod Analytical for their generous gift of HiChrom silica.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dolan JW, Snyder LR, Djordjevic NM, Hill DW, Saunders DL, Van Heukelem L, Waeghe TJ. J. Chromatogr. A. 1998;803:1. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(97)01293-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hancock WS, Chloupek RC, Kirkland JJ, Snyder LR. J. Chromatogr. A. 1994;686:31. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(94)00077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu PL, Snyder LR, Dolan JW, Djordjevic NM, Hill DW, Sander LC, Waeghe TJ. J. Chromatogr. A. 1996;756:21. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(96)00721-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diehl DM, Grumbach ES, Mazzeo JR, Neue UD. Abstracts of Papers of the American Chemical Society. 2004;227:U58. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dolan JW, Maule A, Bingley D, Wrisley L, Chan CC, Angod M, Lunte C, Krisko R, Winston JM, Homeier BA, McCalley DV, Snyder LR. J. Chromatogr. A. 2004;1057:59. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2004.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krisko RM, McLaughlin K, Koenigbauer MJ, Lunte CE. J. Chromatogr. A. 2006;1122:186. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.04.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Makarov A, LoBrutto R, Kazakevich Y. J. Liq. Chrom. Rel. Technol. 2008;31:1533. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marin A, Barbas C. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2006;40:262. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2005.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pellett J, Lukulay P, Mao Y, Bowen W, Reed R, Ma M, Munger RC, Dolan JW, Wrisley L, Medwid K, Toltl NP, Chan CC, Skibic M, Biswas K, Wells KA, Snyder LR. J. Chromatogr. A. 2006;1101:122. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.09.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mao Y, Carr PW. Anal. Chem. 2000;72:110. doi: 10.1021/ac990638x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mao Y, Carr PW. Anal. Chem. 2000;72:2788. doi: 10.1021/ac991435b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melander W, Stoveken J, Horvath C. J. Chromatogr. 1980;199:35. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Destefano JJ, Lewis JA, Snyder LR. Lc Gc. 1992;10:130. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan LC, Carr PW, Abraham MH. J. Chromatogr. A. 1996;752:1. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka N, Kimata K, Hosoya K, Miyanishi H, Araki T. J. Chromatogr. A. 1993;656:265. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wheeler JF, Beck TL, Klatte SJ, Cole LA, Dorsey JG. J. Chromatogr. A. 1993;656:317. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(93)80807-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marchand DH, Snyder LR, Dolan JW. J. Chromatogr. A. 2008;1191:2. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.10.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilroy JJ, Dolan JW, Carr PW, Snyder LR. J. Chromatogr. A. 2004;1026:77. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2003.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilroy JJ, Dolan JW, Snyder LR. J. Chromatogr. A. 2003;1000:757. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(03)00512-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marchand DH, Croes K, Dolan JW, Snyder LR. J. Chromatogr. A. 2005;1062:57. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2004.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marchand DH, Croes K, Dolan JW, Snyder LR, Henry RA, Kallury KMR, Waite S, Carr PW. J. Chromatogr. A. 2005;1062:65. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson NS, Gilroy J, Dolan JW, Snyder LR. J. Chromatogr. A. 2004;1026:91. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2003.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bicker W, Lammerhofer M, Keller T, Schuhmacher R, Krska R, Lindner W. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:5884. doi: 10.1021/ac060680+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]