Abstract

Two patients with giant, 8 cm and 19 cm melanomas of the upper extremity, respectively, are presented and discussed. Both patients had neglected their tumours and sought medical attention only after the appearance of distressing symptoms (for example, bleeding). Palpable lymph nodes were found on physical examination but no evidence of distant metastases was noted on imaging studies despite such enormous primary tumours. Both patients underwent aggressive treatment, including complete surgical resection of the primary tumour and ipsilateral axillary lymph node dissection. One patient had no evidence of local recurrence, but developed metastatic disease at 6 months follow-up. The other patient developed local recurrence and distant metastases within 2 months of resection.

Background

Melanoma is usually regarded as a small but aggressive tumour with the potential for both local recurrence and distant metastasis. Under the current American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging system, the largest tumour size (T) category, T4, includes all lesions with a thickness of >4 mm. In developed, industrialised countries, it is rare to see melanomas that are even 1 cm in size, let alone 8 or 19 cm.

The two cases of giant melanomas in this report and subsequent review of similar cases from the literature describe the initial presentation, management, and outcome of an atypical form of a relatively common cancer. Interestingly, patients with giant melanomas also tend to have local, nodal metastases but not distant metastases. In our two patients, surgical resection of the primary tumour led to rapid development of distant metastases. This phenomenon, also seen in other reported cases of giant melanoma, compels us to re-examine our current understanding of the biology of this disease, specifically the mechanisms regulating metastasis.

Case presentation

Patient A

An 88-year-old man with hypothyroidism and Parkinson’s disease was brought to medical attention by his family after noting a neglected, enormous mass on the extensor surface of his left upper arm. The patient denied any pain or disability associated with the mass, but reported occasional light bleeding. Of note, the patient had a sister who had died at a young age from metastatic melanoma.

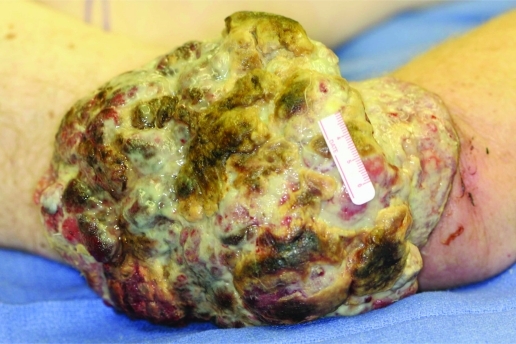

On physical examination, the patient had a fungating, cauliflower-like mass that measured 10×8×3 cm (fig 1) with maggots in the centre and erythema in the surrounding skin. The patient had one palpable node in the ipsilateral axilla. Magnetic resonance imaging (MR)I did not show deep invasion past the deep fascia, and positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) imaging did not show any evidence of distant metastases. Biopsy of the primary mass and enlarged axillary node were both positive for melanoma.

Figure 1.

Giant melanoma of the left upper arm in patient A.

Patient B

A 63-year-old man presented with an extremely large, ulcerated mass on the extensor surface of his right upper arm. He had first noted a lesion at this location at least 1 year ago, but had ignored it and sought medical attention only recently as the mass became progressively more difficult to care for and began to bleed. The patient had no known medical conditions. His family history included a sister who had had melanoma but was alive and well.

In our clinic, the patient was noted to have a malodorous, cerebreform mass that measured 23×21×6 cm (fig 2). Physical examination did not demonstrate any motor, sensory or vascular deficits in the distal forearm or hand. The patient had two palpable, matted lymph nodes in the ipsilateral axilla, but no other evidence of lymphadenopathy.

Figure 2.

Giant melanoma of the right upper arm in patient B.

Laboratory evaluation was notable for a low haematocrit which required blood transfusion. MRI was performed which suggested invasion through the superficial fascia and involvement of the distal triceps, brachialis and proximal brachioradialis muscle. The PET/CT scan showed increased uptake at the primary site and ipsilateral axilla, but demonstrated no other areas of distant disease. Fine needle aspiration biopsy of the lesion suggested squamous cell carcinoma.

Treatment

Patient A

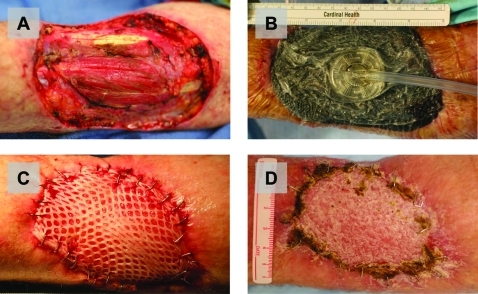

Due to the infected nature of the primary tumour, we elected to perform a two stage operation (fig 3). For the first operation, the mass was resected with a 2 cm circumferential margin to include deep fascia. The resulting defect was copiously irrigated with antibiotic-containing saline and then a wound vacuum system was applied to allow for formation of granulation tissue. The patient recovered well and was discharged home on a course of oral antibiotics.

Figure 3.

Multi-staged excision and skin graft reconstruction in patient A, who had an infected giant melanoma. (A) Wide local excision with a 2 cm circumferential margin to include deep fascia. (B) Application of a wound vacuum system to help promote granulation tissue formation. (C) Completed split-thickness autologous skin grafting of the excision site, performed 6 weeks later. (D) Complete graft uptake, seen several months later at follow-up, with no evidence of local recurrence.

Six weeks later, the patient was taken back to the operating room for placement of a split thickness skin graft harvested from the patient’s contralateral thigh. The original primary excision site had good granulation tissue and no evidence of infection. At the same operation, a left radical axillary lymph node dissection was performed. The patient did well postoperatively and ultimately had complete graft uptake at his left upper arm site.

Patient B

Under general anaesthesia, wide local excision of the mass was performed with a 2 cm circumferential margin which included triceps muscle as part of the deep margin. The defect was covered using a split thickness skin graft harvested from the patient’s contralateral thigh. At the same operation, a right radical axillary lymph node dissection was performed. The patient recovered well postoperatively with minimal deficits in the function of his right arm and complete graft uptake.

Outcome and follow-up

Patient A

The final pathologic diagnosis of the primary tumour was an 8 cm nodular type melanoma, Breslow thickness of 3.1 cm, and Clark level V. No perineural or lymphovascular invasion was noted. The final pathologic diagnosis on the axillary contents was metastatic melanoma with extracapsular extension in level I, but no evidence of disease in level II or III.

Six months after resection of his primary tumour (4 months post-axillary dissection), the patient had no evidence of local recurrence at his left upper arm or axilla. However, multiple new foci of metastatic disease were noted in the vertebral column and ribs on follow-up PET/CT.

Patient B

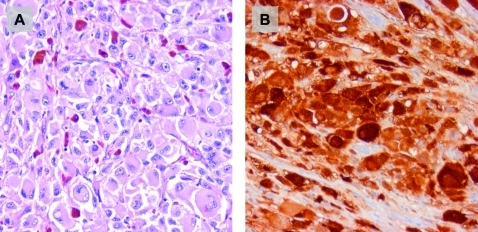

Haematoxylin and eosin stained sections demonstrated a highly cellular, malignant neoplasm composed of large polygonal cells in sheets (fig 4A). Mitotic activity was conspicuous and there was extensive tumour necrosis. Rare cells with “dusty” brown pigment were scattered throughout the tumour. Immunohistochemical stains for S100 (fig 4B), HMB 45 and tyrosinase all showed strong staining. The morphology and immunophenotype confirmed the diagnosis of melanoma and excluded other entities in the differential including squamous cell, basal cell or Merkel cell carcinoma. No perineural or blood vessel invasion was identified. Lymphatic invasion was present. The final pathologic diagnosis was a 19 cm nodular type melanoma, Breslow thickness of 7.5 cm, and Clark level V. Two level I axillary lymph nodes (measuring 6.5 cm and 3.5 cm) out of 42 nodes total were positive for disease.

Figure 4.

Histological examination of tumour specimen in patient B, whose original preoperative biopsy suggested squamous cell carcinoma. Haematoxylin and eosin staining (A) and S-100 immunohistochemistry (B) both confirm melanoma as the final diagnosis.

Less than 2 months after resection, the patient was noted to have in-transit metastases at his graft site and upper arm. MRI of his brain demonstrated multiple sites of hemorrhagic metastases. Adjuvant chemotherapy combined with novel target therapies were discussed at a multidisciplinary tumour board meeting; however, the patient was lost to follow-up.

Discussion

Cutaneous melanoma of such massive size is rarely seen in developed, industrialised countries, especially with the success of current public screening and prevention programmes. A review of the recent literature demonstrates isolated case reports which describe patients who present with giant melanomas of various anatomic sites, including the back,1,2 abdomen,3 scalp,4 eyelid5 and thumb.6 To our knowledge, patient B—who had a 19 cm diameter lesion—represents the largest primary melanoma of the upper extremity and one of the largest melanomas of all reported to date.

Based on size alone, the current TNM staging system for melanoma designates our two patients’ tumours as T4, which in actuality includes all lesions with a thickness >4 mm (not cm). Lymph node status has been shown in two large series of T4 melanomas to be the most important prognostic indicator for survival.7,8 Five year survival rates differ by almost twofold in node negative versus node positive patients. Independent of lymph node status, prognosis in T4 melanomas also depends on several other factors including absolute thickness, ulceration, and vascular involvement.Regardless of size, melanomas that are polypoid or exophytic are associated with increased malignant potential and overall, worse prognosis.9–11 These tumours demonstrate a nodular growth pattern and often are thicker and ulcerated at the time of presentation. Five year survival rates in small case series range from 33–42%. A case report of a patient with a preauricular polypoid melanoma describes local and regional recurrence <1 month after surgical excision.12

Despite the extremely large size of the melanomas in our two patients, what is remarkable is that although both patients had regional lymphadenopathy, neither had evidence of distant metastases at initial presentation. This pattern of local spread without distant disease in such massive melanomas was also noted in several other case reports1,4,5 found on review of the literature. Conventional sized melanomas are thought to follow a paradigm of orderly disease progression from primary site to regional lymph nodes and subsequently to distant sites.13–15 It is interesting that even at such enormous sizes, these melanomas still appear to follow this paradigm.

Equally intriguing is the rapid development of metastases after primary tumour resection, seen in both our patients. Primary tumour induction of tumour dormancy at distant sites has been observed in animal models and multiple tumour types.16,17 Although still controversial, the mechanism for this phenomenon may be related to production of circulating angiogenesis inhibitors by the primary tumour.18,19 In addition, host immune cells at the tumour site may help maintain a state of equilibrium between slowly proliferating tumour cells and those undergoing apoptosis.20,21 In our two patients, it is likely that distant microscopic metastases, not visible on conventional imaging, were already present at initial presentation. We hypothesise that primary tumour resection may have removed the source of endogenous inhibitory factors or somehow altered immune surveillance mechanisms to allow for outgrowth of distant metastases. Further investigation with a larger cohort of patients would be needed to make any firm conclusions.

Given the rarity of giant melanomas, it is also difficult to draw conclusions as to an appropriate management strategy. We and others1,2,4–6 support an attempt at cure with multimodality treatment, including aggressive surgical resection. Even if cure is not achieved, palliative debulking may at least offer symptom control (for example, local infection and bleeding). As giant melanomas have several poor prognostic factors (size, exophytic growth, ulceration, nodal disease), consideration should also be given to experimental treatment regimens and novel therapeutic agents.

Learning points

Melanomas can present, in rare circumstances, as giant, multi-centimetre tumours.

Giant melanomas appear to follow orderly progression first to lymph nodes, then distant sites.

Aggressive multimodality treatment should be offered to patients, but efficacy of this approach is inconclusive due to rarity of these melanomas.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication

REFERENCES

- 1.Harting M, Tarrant W, Kovitz CA, et al. Massive nodular melanoma: a case report. Dermatol Online J 2007; 13: 7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisen DB, Lack EE, Boisvert M, et al. Giant tumor of the back. Arch Dermatol 2002; 138: 1245–50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Giorgi V, Massi D, Carli P. Giant melanoma displaying gross features reproducing parameters seen on dermoscopy. Dermatol Surg 2002; 28: 646–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panajotovic L, Dordevic B, Pavlovic MD. A giant primary cutaneous melanoma of the scalp--can it be that big? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2007; 21: 1417–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pai RR, Kini H, Kamath SG, et al. Giant hanging melanoma of the eyelid skin. Indian J Ophthalmol 2008; 56: 239–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeebregts CJAM, Schraffordt Koops H. Giant melanoma of the left thumb. Eur J Surg Onc 2000; 26: 189–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heaton KM, Sussman JJ, Gershenwald JE, et al. Surgical margins and prognostic factors in patients with thick (>4 mm) primary melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol 1998; 5: 322–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zettersten E, Sagebiel RW, Miller JR, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with thick cutaneous melanoma (>4 mm). Cancer 2002; 94: 1049–56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siminovitch JM, Bergfeld W, Dinner M. Exophytic (pedunculated) malignant melanoma – Cleveland Clinic experience. Ann Plast Surg 1980; 5: 432–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manci EA, Balch CM, Murad TM, et al. Polypoid melanoma, a virulent variant of the nodular growth pattern. Am J Clin Pathol 1981; 75: 810–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Plotnick H, Rachmaninoff N, VandenBerg HJ., Jr Polypoid melanoma: a virulent variant of nodular melanoma. Report of three cases and literature review. J Am Acad Dermatol 1990; 23: 880–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeGiorgi V, Massi D, Gerlini G, et al. Immediate local and regional recurrence after the excision of a polypoid melanoma: tumor dormancy or tumor activation. Dermatol Surg 2003; 29: 664–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leong SP, Cady B, Jablons DM, et al. Clinical patterns of metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2006; 25: 221–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leong SP. Paradigm of metastasis for melanoma and breast cancer based on the sentinel lymph node experience. Ann Surg Oncol 2004; 11: 192S–7S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leiter U, Meier F, Schittek B, et al. The natural course of cutaneous melanoma. J Surg Oncol 2004; 86: 172–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Retsky MW, Demicheli R, Hrushesky WJ, et al. Dormancy and surgery-driven escape from dormancy help explain some clinical features of breast cancer. APMIS 2008; 116: 730–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peeters CF, de Waal RM, Wobbes T, et al. Metastatic dormancy imposed by the primary tumor: does it exist in humans? Ann Surg Oncol 2008; 15: 3308–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Reilly MS, Holmgren L, Shing Y, et al. Angiostatin: a novel angiogenesis inhibitor that mediates the suppression of metastases by a Lewis lung carcinoma. Cell 1994; 79: 315–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holmgren L, O’Reilly MS, Folkman J. Dormancy of micrometastases: balanced proliferation and apoptosis in the presence of angiogenesis suppression. Nat Med 1995; 1: 149–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koebel CM, Vermi W, Swann JB, et al. Adaptive immunity maintains occult cancer in an equilibrium state. Nature 2007; 450: 903–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Udagawa T. Tumor dormancy of primary and secondary cancers. APMIS 2008; 116: 615–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]