Abstract

A 67-year-old man with a history of multiple myeloma (treated with chemotherapy) was referred with a left hyperaemic conjunctival lesion covering almost 360° of the limbus and extending onto the corneal surface. Conjunctival biopsy revealed conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia. Initial treatment consisted of topical and intralesional injections of interferon α-2b. The patient subsequently developed limbal stem cell deficiency resulting in a persistent non-healing corneal epithelial defect. This was successfully managed with total excisional biopsy of the lesion, combined with limbal stem cell autograft (from the fellow eye) and amniotic membrane transplantation. Histopathology revealed a conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma. The corneal epithelium completely healed postoperatively and there is no evidence of tumour recurrence at 1 year follow-up. This case highlights a rare case of advanced ocular surface neoplasia causing secondary limbal stem cell deficiency. Medical and surgical management of ocular surface neoplasia with limbal stem cell transplantation is effective in treating such cases.

Background

Ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN: conjunctival or corneal intraepithelial neoplasia / squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva) is a rare form of ocular surface neoplasia that usually presents as a perilimbal lesion affecting the bulbar conjunctiva. Limbal stem failure secondary to ocular surface neoplasia is rare. We present a case of advanced OSSN that resulted in limbal stem failure in an elderly Caucasian male on chemotherapy for multiple myeloma.

Case presentation

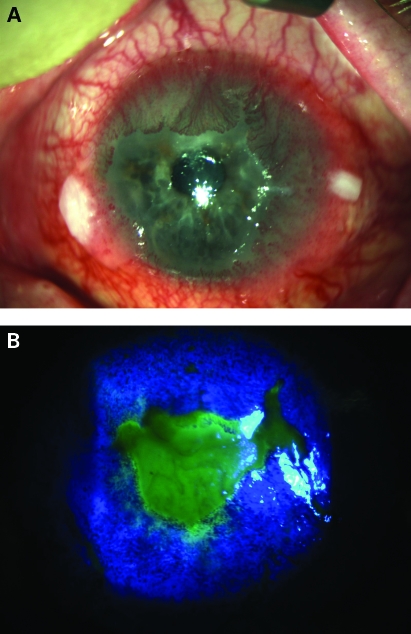

A 67-year-old Caucasian male was referred to our eye department with a left conjunctival lesion of 5 months duration. Slit lamp biomicroscopy revealed a 360° raised, hyperaemic limbal lesion with extensive conjunctival vessels extending onto the corneal surface in the left eye (fig 1A). The patient had no past ocular history. Past medical history was significant for relapsing IgG multiple myeloma for which he had been treated with chemotherapy on six occasions since 2002. Most recent chemotherapy was with Melphalan and dexamethasone. Conjunctival biopsy performed under local anaesthesia revealed conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia. Initial treatment consisted of topical and intralesional injections of 1.5 million IU of interferon α-2b. The patient subsequently developed limbal stem cell failure due to the extensive perilimbal lesion resulting in a central non-healing corneal epithelial defect (fig 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) Advanced conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia extending onto the cornea and leukoplakic nodules. (B) Central epithelial defect secondary to limbal stem cell deficiency seen after instillation of fluorescein eye drops and viewed under cobalt blue light illumination.

Investigations

Initial conjunctival biopsies revealed conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia. In situ hybridisation for human papilloma virus (HPV) types 16 and 18 were negative from all samples of biopsied tissue. Staining for p53 showed strong positivity of the nuclei within the basal epithelium.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of OSSN would normally include a conjunctival papilloma. The other clinical differential diagnosis that was entertained was an extramedullary plasmacytoma as our patient had an underlying medical history of multiple myeloma.

Treatment

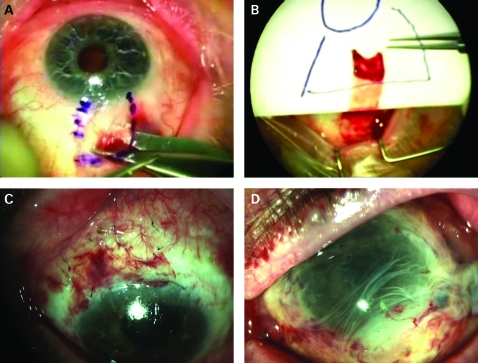

As the patient was not responding to topical and intralesional alpha interferon therapy, total excisional and intraoperative cryotherapy (double freeze thaw technique) to the conjunctival margins combined with a limbal stem cell autograft (from the fellow eye) and amniotic membrane graft was performed under local anaesthesia (fig 2).

Figure 2.

(A) Removal of limbal stem cell autograft from right eye. (B) Transferring graft to left eye on plate, correctly orientated so limbal edge identifiable. (C) Following removal of the neoplasia, the stem cell autograft is sutured to the superior limbus of the left eye. (D) Initial postoperative appearance with amniotic membrane graft in situ.

Outcome and follow-up

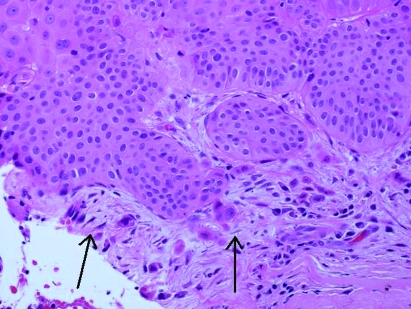

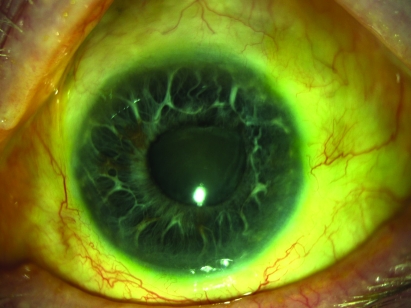

Histological examination confirmed conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia on the temporal side (fig 3). In addition, on the nasal side there was individual cell infiltration through the basement membrane representing early invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Follow-up examination showed total resolution of the tumour with a well healed conjunctival and corneal epithelium with respective phenotypes. The patient continues to remain tumour-free at 12 months follow-up (fig 4).

Figure 3.

Nasal biopsy showing focal early invasive squamous cell carcinoma with individual cellular infiltration (arrowed; haematoxylin and eosin ×400).

Figure 4.

Following degeneration of the amniotic membrane, re-epithelialisation of the corneal surface can be seen. At 12 months follow-up the superior limbal stem cell autograft is barely visible with no evidence of tumour recurrence.

Discussion

OSSN is a rare tumour with an incidence rate of 17 to 20 cases per million per year.1 Various appearances are described, the most common being a vascularised, slightly elevated lesion, greyish in colour, demarcated from the surrounding conjunctiva. Other clinical appearances described include nodular, diffuse, gelatinous, leukoplakic or papilliform.2 Several topical treatments have been reported in treating OSSN including topical mitomycin C and topical and intralesional interferon α-2b.1,3

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most advanced in the spectrum of OSSN. This occurs when malignant epithelial cells invade through the basement membrane into the submucosa.2 This occurs rarely in approximately 3% of OSSN cases. Advanced cases of squamous cell carcinoma carry a higher recurrence rate after surgical excision and are most likely to do so within the first 2 years.2 Although squamous cell carcinoma is regarded as a low grade malignancy, intraocular spread has been reported in 2–11% of cases and death from metastatic spread in up to 8% of cases.4 Advanced corneoscleral limbal spread can lead to destruction of the epithelial stem cells that reside in papillary structures known as the palisades of Vogt.5,6 OSSN has been reported as an extremely rare cause of limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD).5

The aetiology of LSCD is varied. Congenital causes include aniridia and ectodermal dysplasia. Acquired causes include Stevens–Johnsons syndrome, ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, thermal or chemical injury and iatrogenic causes in the form of extensive contact lens wear, topical chemotherapy such as mitomycin C, and previous surgery with cryotherapy.7,8 OSSN causing LSCD is extremely rare with only a few individual cases reported in the literature.5,6,9,10 The aim of treating LSCD is to re-establish a stable ocular surface with regression of vascularisation and to maintain a smooth corneal surface allowing good visual performance.8 The aim of initial management in cases of partial LSCD is to optimise the condition of the corneal surface. This can be done by frequent lubrication, bandage contact lens insertion, tarsorrhaphy or debridement of the conjunctival epithelium which encourages the exposed area to be repopulated with corneal epithelium.8,11 In cases of total limbal stem cell deficiency, the aim of surgical treatment is to establish a new source of corneal epithelium. Several techniques are described in achieving this through limbal transplantation with or without keratoplasty. In unilateral cases of LSCD, the other eye can be used as a donor for providing healthy limbal stem cells.5,12 An autograft has the added benefit of not requiring immunosuppression.

Several aetiological factors have been associated with OSSN development. These include HIV and HPV infection and increased sun exposure.13 HPV infection had previously been excluded in this case. However, he did have a history of myeloma. It is thought that immunosuppression induced by his chemotherapy is the underlying cause of why the lesion progressed to such an advanced state in a relatively short period of time.

In conclusion, we report a rare case of OSSN that resulted in total LSCD which was successfully managed with limbal stem cell graft and ocular surface reconstruction with amniotic membrane graft.

Learning points

Squamous cell carcinoma is an extremely rare cause of unilateral corneal limbal stem cell deficiency.

Total excision and cryotherapy combined with limbal stem cell transplantation from the fellow eye is an effective option to treat large tumours with secondary limbal stem cell failure.

Amniotic membrane transplantation is used in addition to limbal stem cell transplantation to aid epithelialisation of the corneal surface and minimise inflammation.

A limbal autograft of 90° or less is recommended in order to avoid iatrogenic stem cell deficiency in the donor eye.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication

REFERENCES

- 1.Hamam R, Bhat P, Foster CS. Conjunctival/corneal intraepithelial neoplasia. Int Ophthalmol Clin 2009; 49: 63–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee GA, Hirst LW. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Surv Ophthalmol 1995; 39: 429–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schechter BA, Koreishi AF, Karp CL, et al. Long-term follow-up of conjunctival and corneal intraepithelial neoplasia treated with topical interferon alfa-2b. Ophthalmology 2008; 115: 1291–6, 1296 e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKelvie PA, Daniell M, McNab A, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva: a series of 26 cases. Br J Ophthalmol 2002; 86: 168–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dua HS, Azuara-Blanco A. Autologous limbal transplantation in patients with unilateral corneal stem cell deficiency. Br J Ophthalmol 2000; 84: 273–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamamoto N, Ohmura T, Suzuki H, et al. Successful treatment with 5-fluorouracil of conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia refractive to mitomycin-C. Ophthalmology 2002; 109: 249–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dua HS, Azuara-Blanco A. Limbal stem cells of the corneal epithelium. Surv Ophthalmol 2000; 44: 415–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hatch KM, Dana R. The structure and function of the limbal stem cell and the disease states associated with limbal stem cell deficiency. Int Ophthalmol Clin 2009; 49: 43–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meallet MA, Espana EM, Grueterich M, et al. Amniotic membrane transplantation with conjunctival limbal autograft for total limbal stem cell deficiency. Ophthalmology 2003; 110: 1585–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson DF, Ellies P, Pires RT, et al. Amniotic membrane transplantation for partial limbal stem cell deficiency. Br J Ophthalmol 2001; 85: 567–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dua HS, Saini JS, Azuara-Blanco A, et al. Limbal stem cell deficiency: concept, aetiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis and management. Indian J Ophthalmol 2000; 48: 83–92 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kenyon KR, Tseng SC. Limbal autograft transplantation for ocular surface disorders. Ophthalmology 1989; 96: 709–22; discussion 722–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiire CA, Dhillon B. The aetiology and associations of conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia. Br J Ophthalmol 2006; 90: 109–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]