Abstract

Segmental absence of intestinal musculature (SAIM) is a rare entity of uncertain aetiology. A case of SAIM in an adult is presented, and three other adult cases of SAIM are reviewed. Our case concerns a middle-aged man who underwent a Whipple’s procedure for a suspected neoplasm in the head of the pancreas. At surgery, a redundant segment of proximal jejunum with multiple large diverticula was incidentally noted and resected. On histological examination, the small bowel segment showed focal extreme thinning of the muscularis propria, focally amounting to complete absence. A peritoneal biopsy was also submitted which showed changes consistent with an old thrombosed vessel.

BACKGROUND

The gastrointestinal tract has four distinct functional layers: mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria and adventitia. The muscularis propria (main intestinal musculature) consists of smooth muscle that is usually arranged as an inner circular layer and an outer longitudinal layer.1 Segmental absence of intestinal musculature (SAIM) is a rare but recognised entity in neonates. It is a very rare entity in adults and apparently only a few cases have been reported worldwide. The importance of this case report comes from the fact that it represents an incidental finding of this entity in an adult who had no history of intestinal problems. It may be underdiagnosed and some cases of stercoral perforation may be caused by SAIM.

CASE PRESENTATION

A middle-aged man suffered an episode of acute pancreatitis. Computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a mass in the pancreatic head which appeared to be a malignant pancreatic tumour. After discussion in the multi-disciplinary team meeting, the patient was listed for elective Whipple’s procedure (pancreaticoduodenectomy). His past medical history was significant for previous myocardial infarction, previous pulmonary thromboembolism, mixed connective tissue disease, previous repair of hiatus hernia, anaemia and Raynaud’s disease. Apparently, there was no history of bowel obstruction or any significant gastrointestinal symptoms.

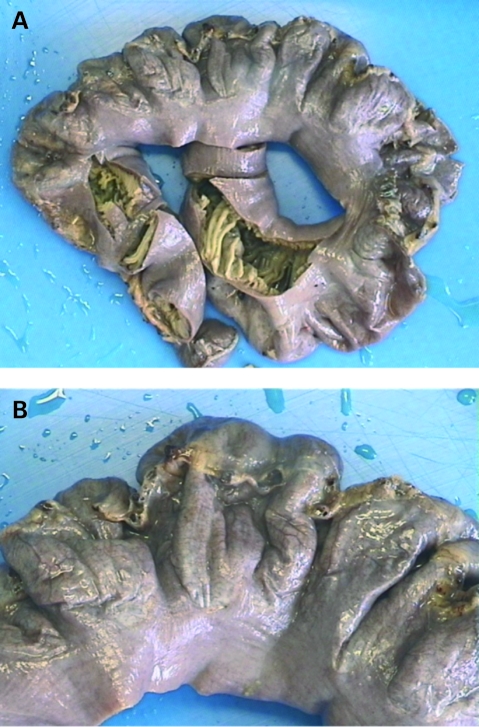

During the Whipple’s procedure, the patient was found to have a dilated and redundant segment of jejunum with multiple wide-neck diverticula (fig 1). A resection of this segment was undertaken. The remaining bowel appeared normal. Postoperatively the patient made an uneventful recovery and was discharged 13 days later.

Figure 1.

(A, B). Gross photograph of the resected jejunum with multiple wide-neck diverticula.

INVESTIGATIONS

Pathological findings: The specimen sent to the pathology laboratory included a peritoneal biopsy, a Whipple’s specimen and the separate segment of small bowel as described above (400 mm in length).

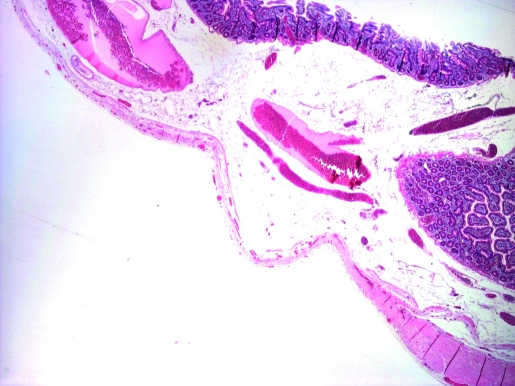

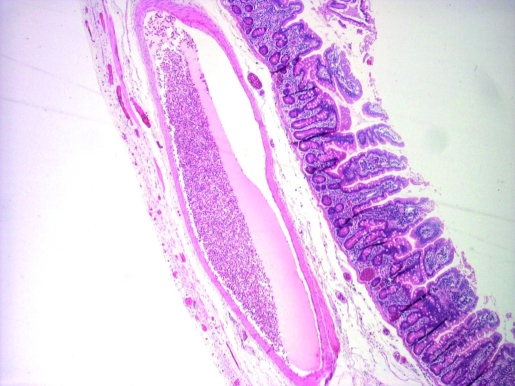

Microscopically, the small bowel segment showed focal extreme thinning of the muscularis propria (fig 2), focally amounting to complete absence (fig 3). There was no associated scarring or inflammatory changes. The part of the duodenum in the Whipple’s specimen showed similar changes. There were no associated features of chronic ischaemia. There was no evidence of pancreatic malignancy; however there was a benign lymphangioma in the duodenal papilla.

Figure 2.

Progressive thinning of muscularis propria.

Figure 3.

Complete absence of the muscularis propria.

Surprisingly, the peritoneal biopsy showed fibroadipose tissue containing a fibrous nodule surrounded by remnants of an elastic lamina. This was interpreted as an old thrombosed vessel which had become fibrosed.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Ischemic bowel disease

Diverticular disease

TREATMENT

The dilated redundant segment of the jejunum was surgically resected.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient is well 4 years after surgery with no further intestinal problems.

DISCUSSION

Since the first description by Herbert in 1943,2 there have been fewer than 30 cases of SAIM.3 These cases mainly occurred in premature infants who had a very low birth weight and presented with obstruction, perforation or intussusception.4

To our knowledge, only three adult cases of SAIM have been reported worldwide.2,3,5 SAIM usually involves the small intestine as in our case; however there has been a reported colonic case.3

In two out of three SAIM adult documented cases, the patients presented with symptoms of bowel obstruction2,5 and in the other case it was an incidental finding after endoscopic perforation for a non-bowel related indication.3

The precise aetiology of SAIM is uncertain and is still a matter of debate. Most of the theories about the aetiology were concluded from neonatal cases. Husain et al6 classified SAIM into two groups: primary and secondary. In the primary group, the aetiology is unknown, the onset of symptoms is acute, and there are no pathological findings in the remaining layers of the small bowel except for superimposed perforation, or intussusception. In the secondary group, there is a longer history of intestinal symptoms and of multiple surgical procedures. Histologically, there may be ischaemic necrosis of remaining layers, fibrosis, calcification, chronic inflammation, and presence of macrophages. These findings indicate secondary destruction (atrophy) of muscle layers due to ischaemia or trauma.

There have been several proposed theories of the pathogenesis of SAIM, such as:

Abnormal embryogenesis leading to incomplete or discontinuous myogenesis.2,6,7

An ischaemic event during fetal life or postnatally leading to injury of both mucosa and muscularis propria, and differences in the regenerative capacity between mucosa and muscle, in which mucosa rather than muscle regenerates, resulting in exclusive absence of the musculature.8,9 A noteworthy fact is that animal studies have not yet been successful in producing such a lesion.3 Ligation of the mesenteric vessels causes intestinal atresia involving all the three layers of the intestinal wall.2

Genetic and familial factors have been postulated in some cases,2,10 however some investigators do not support this theory as there is not enough evidence.3

Some authors believe that this malformation could be a relic of developmental diverticula in the embryonic small bowel.3,11,12 Others believe that it could also result from resorption of ileal muscle at the time of regression of the omphalomesenteric duct, considering the frequency of proximity to the site of Meckel’s diverticula.3,11

The theory concerning ischaemic event seems most likely in our case. According to the study of Darcha et al,3 which was published in 1996, there have never been reports of muscle necrosis, vascular thrombosis or fibrosis in cases of genuine SAIM, as opposed to several neonatal cases where there was evidence of a recent ischaemic event. Findings such as “muscle bundle with loss of nuclei and pink amorphous sarcolemic change, focal myenteric plexus absence, and irregularity of villous arrangement suggesting regenerative change in the mucosa” were noted.4,9 In our case, a thrombosed blood vessel was found in the peritoneal biopsy. Whether this finding is strong enough to draw any conclusions is a debatable matter.

However, it is worth arguing that this finding can explain why a secondary cause of SAIM can look like a primary cause as per Husain et al.6 Our patient probably had an ischaemic event in the past and due to the regenerative capacity of the mucosa, only the muscle sustained long term changes which better fit the pathological description of the primary group of the Husain et al classification, despite it being more likely to be a secondary case. However, this does not explain why there is no fibrosis after the assumed ischaemic event.

On the other hand, in the adult reported cases, one described a 34-year-old male who underwent three-vessel coronary arterial bypass grafts indicating severe early onset of cardiovascular disease.2 In our case, the patient had an myocardial infarction at the age of 53, but whether these two cases point toward ischaemic event is also a debatable matter.

LEARNING POINTS

SAIM is a rare condition which particularly in adults appears to be under-diagnosed.

It maybe mistaken for ischaemic perforation and could even be the cause of many cases of stercoral perforation.

The aetiology and pathogenesis are still uncertain, but many findings point toward an ischaemic event possibly during fetal development.

Further reports will aid in better understanding of this entity which should be included in the differential diagnosis of bowel perforation.

Acknowledgments

Dr Cordelia Phelan for her advice and support.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Young B, Lowe JS, Stevens A, et al. Wheater’s functional histology: a text and colour atlas. 5th edn London: Churchill Livingstone, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tawfik O, Newell B, Lee KR. Segmental absence of intestinal musculature in an adult. Dig Dis Sci 1998; 43: 397–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Darcha C, Orliaguet T, Levrel O, et al. Absence segmentaire de musculeuse colique. A propos d’un cas chez l’adulte. Ann Pathol 1997; 17: 31–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang SF, Vacanti J, Kozakewich H. Segmental defect of the intestinal musculature of a newborn: evidence of acquired pathogenesis. J Pediatr Surg 1996; 31: 721–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pavlovsky Z, Habanec B, Hermanova M, et al. Segmentalni chybeni strevni svaloviny. Cesk Patol 2003; 39: 85–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Husain AN, Hong HY, Gooneratne S, et al. Segmental absence of small intestinal musculature. Pediatr Pathol 1992; 12: 407–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solowiejczyk M, Koren E, Deligdish L, et al. Congenital absence of coats in the intestinal wall. Int Surg 1974; 59: 367–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Villiers DR. Ischemia of the colon: an experimental study. Br J Surg 1966; 53: 497–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morikawa N, Namba S, Fujii Y, et al. Intrauterine volvulus without malrotation associated with segmental absence of small intestinal musculature. J Pediatr Surg 1999; 34: 1549–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steiner DH, Maxwell JG, Rasmussen BL, et al. Segmental absence of intestinal musculature; an unusual case of intestinal obstruction in the neonate. Am J Surg 1969; 118: 964–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alawadhi A, Chou S, Carpenter B. Segmental agenesis of intestinal muscularis: a case report. J Pediatr Surg 1989; 24: 1089–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCarthy DW, Qualman S, Besner GE. Absent intestinal musculature: anatomic evidence of an embryonic origin of the lesion. J Pediatr Surg 1994; 29: 1476–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]