Abstract

A 79-year-old man presented to the Emergency Department with abdominal pain 1 day after an elective total knee replacement. The patient was confused and drowsy, with a high fever, hypotension and uncontrolled atrial fibrillation. He subsequently developed respiratory failure, requiring admission to intensive care. It was then noted that a large pleural effusion had developed between two chest radiographs performed only 4 h apart. A pigtail catheter inserted into the pleural space revealed a transudate of pH 7.0 with an amylase of 17 220 U (serum amylase 54 U), and thus a diagnosis of spontaneous oesophageal rupture or Boerhaave syndrome was made. Despite drainage of the pleural space, the patient developed shock and multiorgan failure requiring mechanical ventilation, renal replacement therapy and cardiovascular support. The oesophageal leak was treated conservatively with intercostal tube drainage; the patient made a full recovery and was discharged from hospital 75 days later.

BACKGROUND

Boerhaave syndrome or spontaneous oesophageal rupture is a rare but potentially fatal condition characterised by a transmural tear of the oesophagus and is the most lethal perforation of the gastrointestinal tract.1 The classic clinical presentation is of a middle-aged male with episodes of repeated vomiting or retching followed by lower chest or upper abdominal pain and subcutaneous emphysema. Unfortunately, patients presenting with this syndrome are a heterogeneous group and often present atypically.2–4 Mortality is generally related to the infectious complications of oesophageal rupture (empyaema, mediastinitis and septic shock) and increases with delayed diagnosis. This case describes a 79-year-old man who presented with Boerhaave syndrome following an elective total knee replacement. Unfortunately, little history was available in the Emergency Department because the patient had become critically ill. However, a chest radiograph was undertaken on presentation followed 4 h later by a second radiograph to check the position of a central venous catheter. It was noted that a large pleural effusion developed in this short time period, prompting further investigation of the pleural fluid, which proved diagnostic.

CASE PRESENTATION

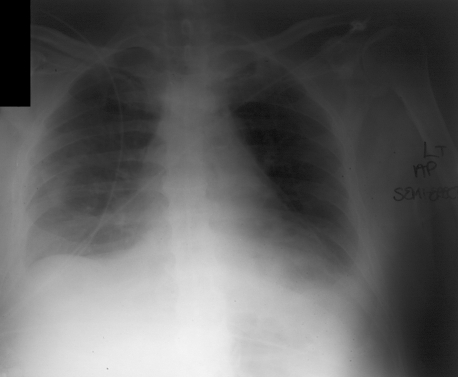

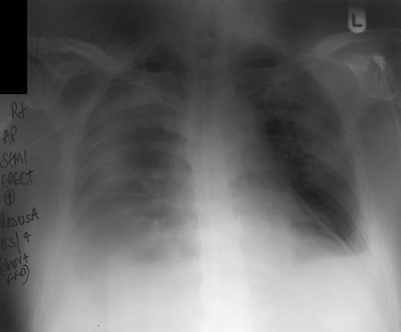

A 79-year-old man with abdominal pain was referred to the emergency surgical team, 1 day after an elective left total knee replacement at an independent orthopaedic centre. Postoperatively, he had complained of abdominal pain, and a nasogastric tube had been placed for a presumed ileus. No additional history was available from the patient, who had now become drowsy and confused. The patient had been independent prior to surgery with no significant past medical history. Examination of the abdomen was unremarkable. However, the patient had a fever of 39°C and was in uncontrolled atrial fibrillation and hypotensive with a blood pressure of 105/45 mm Hg. He was tachypnoeic, but oxygen saturations were maintained at 100% on high-flow oxygen. A chest radiograph was performed (fig 1) at this time. In the absence of an acute abdomen, the patient was referred to the emergency medical team. A right subclavian central line was inserted for fluid management and a further chest radiograph performed to check correct positioning (fig 2). Over the subsequent 8 h, the patient deteriorated, developing crackles throughout the chest and becoming increasingly hypoxic with a rising Paco2, but lactate and base excess remained normal.

Figure 1.

Semierect chest radiograph taken on admission showing bilateral pleural effusions and a tramline at the left heart border suggestive of a pneumomediastinum.

Figure 2.

Semierect chest radiograph taken 4 h after that in fig 1 to check the correct positioning of a right subclavian line, showing massive enlargement of the right pleural effusion with veiling of the entire right hemithorax.

The patient was transferred to intensive care for management of his respiratory failure and haemodynamic instability, and to establish a diagnosis and plan of treatment.

INVESTIGATIONS

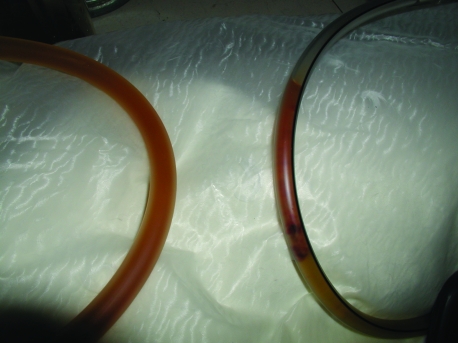

The two chest radiographs were reviewed on admission to intensive care (figs 1, 2). The initial chest film showed bilateral pleural effusions and a tramline adjacent to the left heart border. The second film, taken 4 h later, demonstrated that the right pleural effusion had increased substantially in size. It is unusual for pleural fluid collections to develop over such a short time interval. The insertion of a right subclavian venous catheter raised the possibility of an iatrogenic haemothorax, and so a pigtail catheter was inserted into the pleural space. Two litres of dark fluid matching the nasogastric aspirate drained rapidly (fig 3). Analysis of the pleural fluid demonstrated a transudate with a pH of 7.0 and an amylase of 17 220 U, with a normal serum amylase of 54 U. On the basis of these results, a diagnosis of spontaneous oesophageal rupture or Boerhaave syndrome was made.

Figure 3.

Tubing from the pleural drain (left) and nasogastric tube (right) showing identical contents.

A subsequent computerised tomography (CT) scan of the chest confirmed that the abnormality at the left heart border was a pneumomediastinum. An endoscopy revealed a 1cm tear just above the oesophagogastric junction typical of Boerhaave syndrome.

Subsequent discussion with the patient’s relatives and review of the fluid balance charts established that there had been sustained episodes of vomiting following the knee replacement.

TREATMENT

Despite drainage of the right pleural space, the patient deteriorated further and required mechanical ventilation, vasopressors and haemofiltration. The oesophageal tear was managed conservatively with bilateral intercostal tube drainage, acid-suppression therapy, antibiotics and jejunostomy feeding. Although thoracotomy and repair were considered, it was felt unnecessary, as the tear was small, and adequate drainage was achieved with large intercostal drains.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient remained in intensive care for 21 days and a total of 75 days in hospital before discharge home. The patient returned to his fully independent premorbid state.

DISCUSSION

Spontaneous oesophageal rupture or Boerhaave syndrome is associated with a mortality of around 20% and is usually fatal if left untreated.1,5,6 The mechanism of injury is acute barotrauma caused by vomiting or retching. A transmural tear commonly occurs at the weakest part of the oesophagus, the lower third on the left side where it is covered only by mediastinal pleura. This syndrome frequently presents a diagnostic conundrum, as the classic triad of vomiting or retching, abdominal or chest pain and subcutaneous emphysema is absent in many patients.2–4,6 This should be considered in the differential diagnosis of acute abdominal or chest pain. Delays in diagnosis are inevitably associated with increased mortality, probably as a consequence of late source control.

The majority of reports of Boerhaave syndrome are single case studies or small case series. The most recent large case series by Teh and colleagues6 encompassed 34 patients over a 15-year period in a single thoracic centre and reported an overall mortality of 17.6%. The majority of patients had a late diagnosis (>24 h), and approximately one-third were identified incidentally as a consequence of a CT scan in the absence of any other diagnosis.

The chest radiograph is abnormal in 90% of cases and may show evidence of a pleural effusion (more frequently on the left), pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, hydropneumothorax, subcutaneous emphysema or the V sign of Naclerio.7 The latter is caused by radiolucent streaks of gas in the fascial planes behind the heart, which form the letter V and is a specific but insensitive sign of oesophageal perforation. The unusual radiographic feature in this case, which has not been previously described, was the rapid development of a pleural effusion in a patient who had been fit enough 2 days earlier to have an elective surgical procedure. The differential causes of such an effusion would include haemothorax, chylothorax and oesophageal rupture. However, the findings of a transudate with low pH and very high (salivary) amylase (>2500 U) are typical of oesophageal rupture. The oesophageal tear usually requires surgical management, ideally by primary repair over a T-tube, or by lavage and drainage—rarely oesophageal diversion or even oesophagectomy is necessary.1 Primary repair is generally considered if presentation is not delayed beyond 24 h, but some advocate this procedure for all patients.5 Occasionally, as in this case, where the tear is small, percutaneous insertion of wide-bore intercostal drain is sufficient.6,8 Following appropriate resuscitation antibiotics, acid suppression and enteral nutrition are also essential. Since this disease occurs infrequently, no trials have been undertaken comparing primary surgical repair with a conservative medical approach using intercostal tube drainage, and this remains an area of debate.5,8

LEARNING POINTS

In summary:

Spontaneous oesophageal rupture is a rare, but the most lethal, perforation of the gastrointestinal tract.

Although the classic clinical presentation is of repeated vomiting or retching followed by lower chest or upper abdominal pain and subcutaneous emphysema, the majority of patients do not present in this way.

Delayed diagnosis increases morbidity and mortality.

The chest radiograph is commonly abnormal. Pleural effusions are common, particularly on the left. Pleural fluid characteristically shows by a transudate of low pH with a high amylase (salivary).

Causes of a rapidly developing effusion are serious and require urgent investigation.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication

REFERENCES

- 1.Wolfson D, Barkin JS. Treatment of Boerhaave’s syndrome. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2007; 10: 71–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemke T, Jagminas L. Spontaneous oesophageal rupture: a frequently missed diagnosis. Am Surg 1999; 65: 449–52 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henderson JA, Peloquin AJ. Boerhaave revisited: spontaneous oesophageal perforation as a diagnostic masquerader. Am J Med 1989; 86: 559–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brauer RB, Liebermann-Meffert D, Stein HJ, et al. Boerhaave’s syndrome: analysis of the literature and report of new cases. Dis Esophagus 1997; 10: 64–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jougon J, McBride T, Delcambre F, et al. Primary oesophageal repair for Boerhaave’s syndrome whatever the free interval between perforation and treatment. Eur J Cardiothoracic Surg 2004; 25: 475–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teh E, Edwards J, Duffy J, et al. Boerhaave’s syndrome: a review of management and outcome. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2007; 6: 640–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naclerio EA. The V sign in the diagnosis of spontaneous rupture of the oesophagus (an early roentogram clue). Am J Surg 1957; 93: 291–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Platel JP, Thomas P, Giudicelli R, et al. Oesophageal perforations and ruptures: a plea for conservative treatment. Ann Chir 1997; 51: 611–16 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]