Abstract

Here we describe a case of a secondary bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP), which was associated with repeated respiratory infections caused by carbamazepine (CBZ)- induced hypogammaglobulinaemia. A 49-year-old woman had been treated with CBZ (400 mg/day). Two and a half years later, she developed of dyspnea with productive cough and high-grade fever. Chest roentgenogram and computed tomography showed bilateral infiltrates in lower lung fields. Her laboratory findings revealed severe hypogammaglobulinaemia, suggesting that an immune system disorder caused pulmonary infection. Histological examination by trans-bronchial lung biopsy (TBLB) demonstrated that many foamed alveolar macrophages were obstructing the alveolar ducts and adjacent alveoli, suggesting BOOP. After cessation of CBZ, the hypogammaglobulinaemia and chest roentgenogram findings markedly improved. The present case suggests that CBZ may have some adverse effects on the immune system and cause frequent airway infections, and that secondary BOOP could be induced by repeated infections caused by CBZ-induced hypogammaglobulinaemia.

BACKGROUND

BOOP is a distinct clinicopatholigical entity showing a subacute progression and is characterized histologically by the presence of inflammatory fibrinous plugs obstructing the terminal and respiratory bronchioles (bronchiolitis obliterans) and extending into the alveolar ducts and adjacent alveoli (organizing pneumonia).1 BOOP may result from diverse causes such as drugs, respiratory infections and radiation therapy or appear idiopathically.2 In this report, we describe a case of secondary BOOP, which was associated with repeated respiratory infections caused by CBZ-induced hypogammaglobulinaemia. This is an important adverse effect of a commonly prescribed medication.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 49-year-old woman had been treated with CBZ for 2 years because of epilepsy. She was referred to us for progressive exertional dyspnea and prolonged productive cough in spite of medications by several oral antibiotics. On admission to our hospital, her body temperature was 38.7°C. The lower lobes of bilateral lungs revealed fine crackle sounds during auscultation.

INVESTIGATIONS

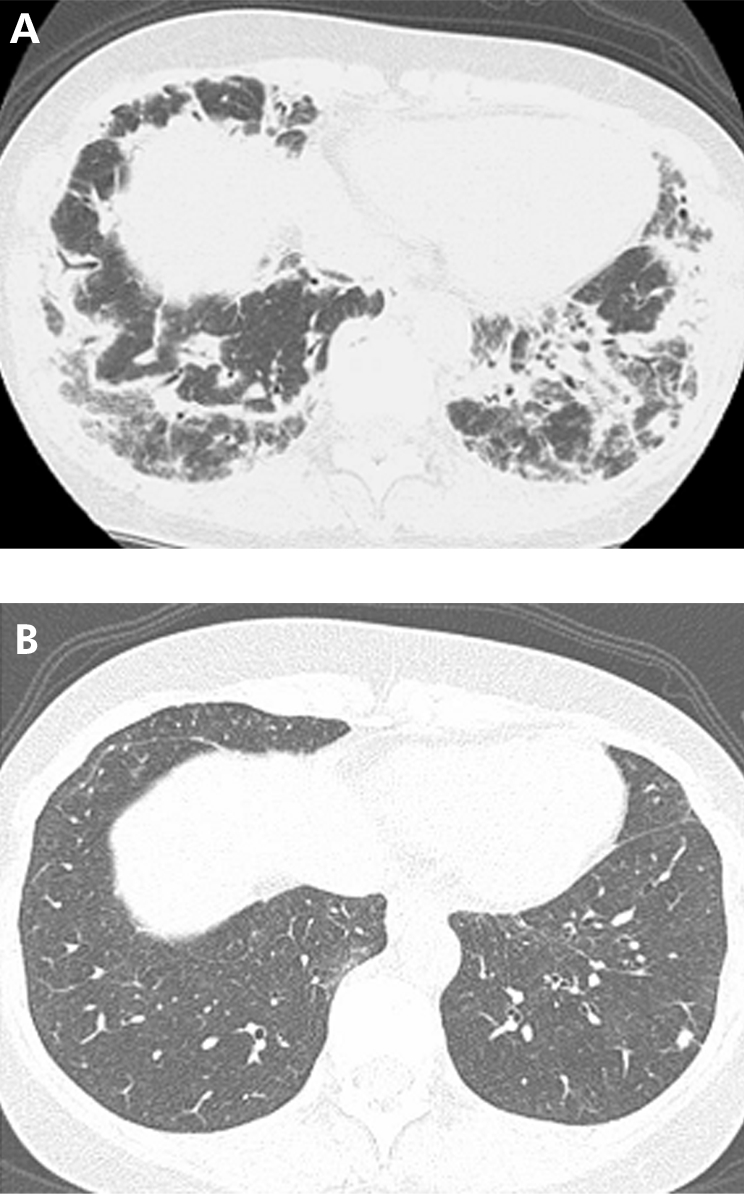

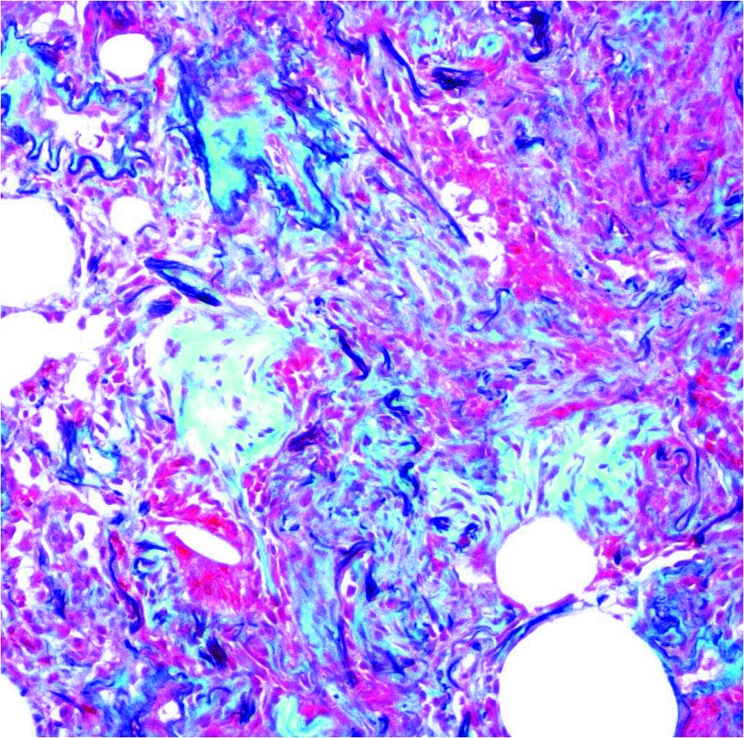

The chest roentgenogram and chest computed tomographic scan (fig 1) showed bilateral infiltrates including ground glass opacities and consolidations predominantly in the lower lung fields. Her laboratory findings showed severe hypogammaglobulinaemia with an increase in C-reactive protein, suggesting a disorder of the immune system. The serum immunoglobulin levels were as follows: IgG 418 mg/dl (normal, 748 to 1694 mg/dl), IgA 20 mg/dl (normal, 91 to 391 mg/dl), and IgM 51 mg/dl (normal, 33 to 254 mg/dl). Both KL-6 and soluble IL-2 receptor were also increased to 1826 IU/l (normal, 0 to 500 IU/l) and 1490 IU/l (normal, 145 to 519 IU/l), respectively. Lymphocyte subpopulation studies demonstrated almost normal counts of T cells and B cells. The serum concentration of CBZ was within the therapeutic range (5.52 μg/ml; normal, 5 to 10 μg/ml). CBZ and other suspected antibiotics were all negative for drug-induced lymphocyte stimulation tests (DLST). Histological examination of specimens from TBLB demonstrated that fibroblastic foci with mild fibrosis as well as many foamed alveolar macrophages were obstructing the alveolar ducts and adjacent alveoli (fig 2). Based on these findings, we made the diagnosis of BOOP.

Figure 1. (A) Chest CT scans on admission. Bilateral infiltrates including ground glass opacities and consolidations are seen predominantly in lower lung fields.

(B) Chest CT scans seven months after the cessation of carbamazepine showing marked improvement. The serum levels of Ig G, Ig A and Ig M are also increased to 1328, 69 and 355 mg/dl, respectively.

Figure 2. Elastica-Masson staining of specimens from TBLB.

Immature fibroblastic foci and foamy alveolar macrophages are obstructing the alveolar ducts and adjacent alveoli. These features are consistent with BOOP.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia

TREATMENT

Cessation of carbamazepine.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

After the cessation of CBZ, all abnormalities in laboratory and roentgenogram findings gradually improved without any medication. Seven months after the diagnosis, her chest roentgenogram findings and the serum level of gammaglobulins became almost normal.

DISCUSSION

The pathogenesis of BOOP has not been determined. In most case, BOOP is idiopathic. However, some drugs, respiratory infections and radiation therapies can be a cause of BOOP.1,2 Such secondary BOOP often develops within several weeks and has a relatively acute onset. Additionally, there are two reported cases that are associated with common variable immunodeficiency (CVID). One was a 26 year-old woman with CVID, who had been treated with monthly gamma globulin for 5 years. Despite this replacement therapy, she frequently got respiratory infections, which resulted in BOOP.3 Another was a 38 year-old woman, who had repeated respiratory infections for 3 years and finally developed BOOP. During the steroid therapy for BOOP, she had recurrent pneumonia and was diagnosed as a type of CVID. After the replacement therapy with gamma globulin, she suffered no new infections and the BOOP gradually improved without additional medication.4 These two cases are highly suggestive of the pathogenesis of BOOP with hypogammaglobulinaemia. Although the relationship between B and T cell dysfunction and BOOP has not been determined, it is speculated that an impairment of the B cell function and an inappropriate activation of T cells during the repeated respiratory infections may cause BOOP, which is roughly characterized as a cellular interstitial pneumonitis.

It is unusual that CBZ induces hypogammaglobulinaemia. Therefore, the mechanisms of this adverse effect are difficult to understand. The reported nine cases with CBZ-induced hypogammaglobulinaemia,5–8 can be classified into three groups. In the first group, all classes of immunoglobulins are decreased or lost because of the absence of B cells. A disorder in the proliferation or differentiation of B cells causes the absence of B cells in this group.5 In the second group, the number of B cells is within the normal range, but all classes of immunoglobulins except IgE are remarkably decreased. In this group, the synthesis of immunoglobulins is extensively impaired although the proliferation of B cells is not inhibited.5,8 In the third group, the number of B cells is normal and the serum level of IgM is relatively increased but that of IgG is decreased. It is speculated that a disorder of the class-switch of immunoglobulins and then the absence of maturation from B cells to plasma cells caused the hypogammaglobulinaemia in this group.8 Our case described above would therefore belong to the second group.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of secondary BOOP associated with repeated respiratory infections which were probably caused by CBZ-induced hypogammaglobulinaemia. This case suggests that CBZ may have some adverse effects on the immune system and cause frequent airway infections, and that secondary BOOP could be induced by repeated respiratory infections caused by CBZ-induced hypogammaglobulinaemia.

LEARNING POINTS

A drug-induced hypogammaglobulinaemia after long term use of carbamazepine is very rare.

A hypogammaglobulinaemia should be considered as one of the causes of secondary bronchiolitis obliterans organising pneumonia with repeated airway infections.

Acknowledgments

This article has been adapted with permission from Tamada T, Nara M, Tomaki M, Ashino Y, Hattori T. Secondary bronchiolitis obliterans organising pneumonia in a patient with carbamazepine-induced hypogammaglobulinemia. Thorax 2007;62:100.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cordier JF. Organising pneumonia. Thorax 2000; 55: 318–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cazzato S, Zompatori M, Baruzzi G, et al. Bronchiolitis obliterans-organizing pneumonia: an Italian experience. Respir Med 2000; 94: 702–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gamboa PM, Merino JM, Maruri N, et al. Hypogammaglobulinemia resembling BOOP. Allergy 2000; 55: 580–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaufman J, Komorowski R. Bronchilitis Obliterans Organizing Pneumonia in Common Vriable Immunodeficiency Syndrome. Chest 1991; 100: 552–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castro AP, Redmershi MG, Pastorino AC, et al. Secondary hypogammaglobulinemia after use of carbamazepine: case report and review. Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med Sao Paulo 2001; 56(6): 189–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aihara Y, Ito SI, Kobayashi Y, et al. Carbamazepine-induced hypersensitivity syndrome associeted with transient hypogammmaglobulinemia and reactivation of human herpesvirus 6 infection demonstrated by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Br J Dermatol 2003; 149: 165–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dionysios V, Leontini F, Kyriaki S, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis in a patient with acquired hypogammaglobulinemia. Eur J Intern Med 2001; 12: 127–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Go T. Carbamazepine-induced IgG1 and IgG2 deficiency assosiated with B cell maturation defect. Seizure 2004; 13: 187–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]