Abstract

Defective closure of the posterolateral pleuroperitoneal canal during embryogenesis gives rise to a congenital hernia (usually left sided) which was originally described by Bochdalek in 1948. It manifests primarily in children with respiratory symptoms and pulmonary hypoplasia. It is exceptionally rare for this defect to present in adulthood, with just over 50 symptomatic cases being described in the literature. Most adolescent and adult cases are diagnosed incidentally during imaging for upper gastrointestinal symptoms. It is unusual for adults to present with respiratory symptoms. We describe the case of a 71-year-old man who presented with features of left ventricular failure due to an exceptionally large, right sided Bochdalek hernia. This is the oldest clinical presentation of a right sided Bochdalek hernia, which uniquely included trans-diaphragmatic herniation of the pancreas.

Background

In 1948 Victor Alexander Bochdalek, a professor of anatomy from Prague, described his dissection of a newborn infant who had died from a congenital hernia through a hiatus in the diaphragm through the left posterolateral pleural cavity.1,2 Since then, hernias occurring on the right have also been described, albeit with reduced frequency. These are also designated Bochdalek’s herniae and are thought to occur by the same mechanism. The majority of cases are described in children, but approximately 50 symptomatic cases have been documented in the adult literature. Cases usually involve the left hemidiaphragm (90%).3 The current case is sufficiently exceptional with regard to age, mode of presentation, location and contents of the hernial sac to merit a report.

Case presentation

A 71-year-old retired fork lift driver was referred to outpatients with an 8 week history of dyspnoea on exertion and when lying flat. He had no associated chest pain, palpitations, cough, belching, dysphagia, or odynophagia. His appetite had been normal, with no weight loss or altered bowel habit.

Previous medical history was notable for heartburn and early satiety for which he underwent an endoscopy several years before presentation. This identified a hiatal hernia; symptoms were controlled by lansoprazole 15 mg daily. He had treated hypertension (ramipril 5 mg, bisoprolol 1 0mg, felodipine 2.5 mg), benign prostatic hypertrophy (tamsulosin 400 μg), high cholesterol (simvastatin 20 mg), and asthma (beclomethasone and salbutamol inhalers). He had never smoked and consumed <10 units of alcohol per week. Respiratory and abdominal examination was normal, but an audible diastolic murmur was heard at the lower left sternal edge. His jugular venous pressure (JVP) was not elevated; blood pressure was 143/87 mm Hg and oxygen saturations were normal.

Investigations

Full blood count, renal, liver and thyroid function tests were all normal. A plain chest radiograph showed a large viscus with multiple air–fluid levels projected over the mid and lower zones (fig 1). Echocardiography showed mild aortic regurgitation in the absence of stenosis and left atrial compression from an adjacent posterior structure (fig 2). Exercise tolerance test was normal. A computed tomography (CT) scan revealed that the stomach, a large quantity of small bowel, the transverse colon and the pancreas had herniated into the posterior part of the chest, with the superior part of this hernia at the level of the carina (fig 3). This had caused bibasal pulmonary atelectasis.

Figure 1.

Anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) chest radiographs demonstrating massive herniation of abdominal viscera into the thoracic cavity (arrows).

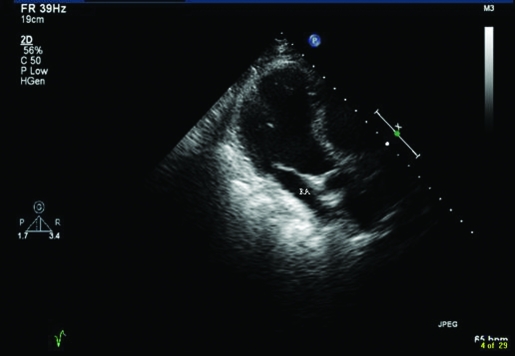

Figure 2.

Echocardiogram (four chamber view) illustrating gross external compression of the heart leading to a slit like right atrial cavity (RA).

Figure 3.

Computed tomography scan showing herniation of the pancreas (small arrow) and small and large bowel viscera (large arrow) into the thoracic cavity.

Treatment

After discussion about the risks of attempting to repair such a large volume of the hernia, the patient elected for conservative, symptomatic treatment.

Outcome and follow-up

Twelve months later he had just returned from a holiday in Cornwall and reported no progression of symptoms.

Discussion

Separation of the thoracic and abdominal cavities occurs in the eighth week of gestation, when closure of the pleuroperitoneal canal takes place. Failure of this process results in a congenital diaphragmatic hernia. In 1948, Bochdalek described incomplete fusion of the posterolateral diaphragmatic foramina, through which abdominal viscera might herniate. Bochdalek stressed that this hernia may not purely be a congenital malformation, but rather the stretching of a defect existent in almost any fetus, resulting in rupture of an intact membrane of the diaphragm referred to as the trigone of Bochdalek.1,2 Subsequent case reports have predominantly described left sided herniation as being more common, as pleuroperitoneal folds preferentially terminate on the right side during embryonic development. It is also conceivable that the liver confers protection to herniation of abdominal contents.2,3

The incidence of diaphragmatic (Bochdalek) herniation in neonates is 1 in 2000–5000.4 Presentation in adulthood is very uncommon; a PubMed search (Bochdalek, hernia, adult) revealed just over 50 reported symptomatic cases. The true prevalence is difficult to estimate, because hernias are increasingly identified by imaging for non-specific symptoms. The largest study to date estimates 0.17% incidence in adults,5 remarkably similar to that in neonates. Various abdominal organs may migrate through the defect. Colonic herniation is most common and may present with obstruction and strangulation.6–8 Herniations of the stomach, small bowel, spleen, omentum, and kidney have also been described.9 The current case included pancreatic herniation, which has not previously been documented.

Principal symptoms at birth are respiratory distress from pulmonary hypoplasia, because intestinal herniation prevents lung maturation. There may be cyanosis, dyspnoea and lateral displacement of the apex of the heart. In adulthood, however, respiratory symptoms are rare. Upper gastrointestinal symptoms, often unusual (vomiting, dyspepsia, or abdominal pain triggered by increased intra-abdominal pressure) are more common.

Chest radiographs may demonstrate diaphragmatic elevation on the affected side and an air–fluid interface, or soft tissue shadows related to solid viscera. Confirmation by CT scan is appropriate.10 It may be misdiagnosed as a pleural effusion or lung cyst.11 High proportions of cases are asymptomatic, or have symptoms that are difficult to attribute to the herniation; careful consideration should then be given to the potential consequences of intervention.

Definitive treatment means operative repair, with reduction of the herniated organs and repair of the defect. Specialist advice is appropriate, because hepatic herniation necessitates thoracotomy, rather than laparotomy, and a laparoscopic assisted approach in experienced hands may reduce morbidity. Congenital diaphragmatic (Bochdalek) herniation should be considered as a differential diagnosis if an incarcerated hiatal hernia is detected on a chest radiograph or at endoscopy.

Learning points

Separation of the thoracic and abdominal cavities via closure of the pleuroperitoneal canal takes place in the eighth week of gestation. Failure of this process results in a Bochdalek’s hernia.

Left sided herniation is more common.

Symptomatic Bochdalek’s hernia usually present in childhood with respiratory distress from pulmonary hypoplasia.

In adulthood, however, respiratory symptoms are rare. Upper gastrointestinal symptoms (vomiting, dyspepsia, or abdominal pain triggered by increased intra-abdominal pressure) are more common.

Congenital diaphragmatic (Bochdalek) herniation should be considered as a differential diagnosis if an incarcerated hiatal hernia is detected on a chest radiograph or at endoscopy.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bochdalek VA. Vjschr. prakt. Heilk 1848; 19: 89 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haller JA. Professor Bochdalek and his hernia: then and now. Prog Pediatr Surg 1986; 20: 252–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mullins ME, Saini S. Imaging of incidental Bochdalek hernia. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 2005; 26: 28–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison MR, de Lorimier AA. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Surg Clin North Am 1981; 61: 1023–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mullins ME, Stein J, Saini SS, et al. Prevalence of incidental Bochdalek’s hernia in a large adult population. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001; 177: 363–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kavanagh DO, Ryan RS, Waldron R. Acute dyspnoea due to an incarcerated right-sided Bochdalek’s hernia. Acta Chir Belg 2008; 108: 604–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terzi A, Tedeschi U, Lonardoni A, et al. A rare cause of dyspnea in adult: a right Bochdalek’s hernia-containing colon. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2008; 16: 42–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kocakusak A, Arikan S, Senturk O, et al. Bochdalek’s hernia in an adult with colon necrosis. Hernia 2005; 9: 284–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alam A, Chander BN. Adult Bochdalek hernia. Med J Armed Forces India 2005; 61: 284–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shin MS, Mulligan SA, Baxley WA, et al. Bochdalek hernia of diaphragm in the adult. Diagnosis by computed tomography. Chest 1987; 92: 1098–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas S, Kapur B. Adult Bochdalek hernia – clinical features, management and results of treatment. Jpn J Surg 1991; 21: 114–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]