Abstract

This case involves a 43-year-old female patient with highly uncontrolled type 2 diabetes for the past 14 years. Her weekly mean (SD) glycaemia (WMG) concentration at week 1 was 20.9 (4.8) mmol/l (377 (87) mg/dl). Four weeks after reaching full control at week 3 with insulin glargine plus regular insulin and metformin (WMG 7.0 (1.9) mmol/l (127 (34) mg/dl)) she was diagnosed with acute pulmonary tuberculosis and treated with rifampicin, isoniazid and pyrazinamide, which caused her to lose glycaemic control (WMG 21.0 (7.1) mmol/l (378 (128) mg/dl)). No other potentially hyperglycaemic drug such as corticosteroid was used. During this entire period she was intensively treated with NPH (neutral protamine Hagedorn) and regular insulins, reaching a total daily dose of 170 IU, but with no clinical response. Together with insulin therapy, rosiglitazone was started at week 12 and glycaemic control returned to normal within just 3 weeks (WMG 6.6 (2.9) mmol/l (120 (53) mg/dl)).

BACKGROUND

Tuberculosis and drugs used for its treatment in diabetic patients promotes a deep negative impact on glycaemic control. This case is important because this effect was adequately and quantitatively evaluated and also because of the significant response to rosiglitazone by a patient who was not responding to insulin doses as high as 170 IU/day and who had her glycaemic control restored to normal just 3 weeks after starting rosiglitazone in addition to insulin treatment at the same daily dose.

CASE PRESENTATION

This case report involves a 43-year-old woman with a history of highly uncontrolled type 2 diabetes for the past 14 years. She was referred by the outpatient department to the Diabetes Education and Control Group of the Kidney and Hypertension Hospital for intensive care and educational intervention. In her first visit she weighed 87.5 kg, with a height of 1.58 m, a body mass index (BMI) of 35 kg/m2, and an abdominal circumference of 113.5 cm. Comorbidities included hypertension, dyslipidaemia and hypothyroidism, and she was being treated with losartan, hydrochlorothiazide, ciprofibrate, and levothyroxine. She had a glycated haemoglobin (A1C) of 12.0% and a fasting blood glucose of 17.2 mmol/l (310 mg/dl), in spite of her ongoing diabetes treatment with metformin (850 mg three times daily), NPH (neutral protamine Hagedorn) insulin (40 IU in the morning and 20 IU at bedtime), and regular insulin (5 IU before lunch). At week 1 she presented with hyperglycaemia and high glycaemic variability (weekly mean (SD) glycaemia (WMG) concentration 20.9 (4.8) mmol/l (377 (87) mg/dl)). Initially, she was started on insulin glargine (40 IU/day) plus regular insulin (4 IU just before meals) and metformin (850 mg three times daily). She had full response to treatment at week 3 (WMG 7.0 (1.9) mmol/l (127 (34) mg/dl)). At week 6 she presented a clinical picture of “respiratory infection”, with malaise, productive cough, fever and mild dyspnoea, later diagnosed as active pulmonary tuberculosis (APT). At week 7 she was back again to poor glycaemic control (WMG 21.0 (7.1) mmol/l (378 (128) mg/dl)), in spite of massive insulin doses reaching 170 IU/day. At week 12 she was started on rosiglitazone (4 mg/day) as add on therapy, with a good therapeutic response at week 13, after which the rosiglitazone daily dose was increased to 8 mg/day and glycaemic control was fully regained at week 15 (WMG 6.6 (2.9) mmol/l (120 (53) mg/dl)).

INVESTIGATIONS

The patient received a glucose monitor and reagent strips (Accu-Chek Active, Roche Diagnostics) to perform three glycaemic profiles of 7 points per week (glycaemic tests were performed seven times a day: fasting, 2 h after breakfast, before lunch, 2 h after lunch, before dinner, 2 h after dinner, and an early morning test between 2–4 am: 21 tests/week). At each weekly visit glycaemic results were downloaded onto a computer with the help of software (Accu-Chek 360°, Roche Diagnostics) in order to calculate the weekly mean (SD) glycaemia (WMG) concentration.

TREATMENT

Tuberculosis treatment was started between weeks 6 and 7 with triple drug therapy: rifampicin, isoniazid and pyrazinamide. Rifampicin accelerates the metabolism of antidiabetic drugs and may increase insulin requirements. Isoniazid antagonises sulfonylureas and may cause pancreatitis, besides intensifying insulin resistance.1 The mechanism of antidiabetic effect of pyrazinamide is not known. A treatment strategy including pharmacological and educational interventions by nurses, nutritionists, psychologists and other related professionals was implemented and the patient was followed-up weekly for 15 weeks. In the first visit the patient was started on insulin glargine (40 IU at bedtime) and regular insulin (4 IU three times daily before meals), together with metformin (850 mg three times daily). At week 12, glargine was replaced by NPH insulin and regular insulin was maintained. Metformin had been discontinued since the start of tuberculosis treatment. At this point, the total insulin dose was reaching 170 IU/day, being 80 IU of NPH and 90 IU of regular insulin.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

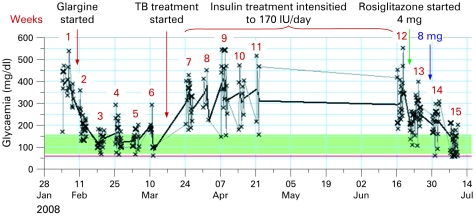

In spite of this massive insulin dose, the patient was not responding to treatment. For this reason, rosiglitazone was started on week 12 at a dose of 4 mg/day, with an initial good response. At week 13, rosiglitazone dose was increased to 8 mg/day and at week 15 the normalisation of glycaemic control was again achieved, with a WMG of 6.6 (2.9) mmol/l (120 (53) mg/dl) (fig 1).

Figure 1.

Weekly mean (SD) glycaemia (WMG) concentration before and during tuberculosis treatment, and the impact of rosiglitazone treatment on glycaemic control (weeks 13 to 15) (see text for details). When utilising the concept of WMG for the evaluation of glycaemic control the following targets should be considered as indications of adequate glycaemic control: WMG <8.3 (2.7) mmol/l (<150 (50) mg/dl).

DISCUSSION

Tuberculosis is a chronic and serious infection which also affects the endocrine function of the pancreas and the adrenal, thyroid and pituitary glands, warranting exogenous insulin and other hormone replacements. Diabetic patients are not only more susceptible to infection but when infections do occur they are more severe, as the diabetic patient is a compromised host.1 Tuberculosis in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is not uncommon, affecting 5–10% of T2DM patients in developing countries.

Adequate glycaemic control seems to reduce the risk of tuberculosis. Diabetic subjects with A1C <7% at enrolment were not at increased risk, but those with A1C >7% were at higher risk of active, culture confirmed, and pulmonary tuberculosis.2 T2DM seems to have a negative effect on treatment outcome of pulmonary tuberculosis,3 but tuberculosis also has a negative impact on treatment outcome of diabetes.1

The decision to start rosiglitazone for this patient was made as a last resort in our efforts to control the resistant hyperglycaemia, even with the use of a 170 IU total daily insulin dose. In fact, our goal was just to try to reduce insulin resistance, and we did not expect such an impressive response. The full mechanism by which this result was obtained is unclear. Could this be interpreted as a modality of serendipity? To our knowledge there are no reports of similar cases of such a significant response to rosiglitazone in restoring glycaemic control in a fully “insulinised” patient. Whether or not this finding could be applicable to the general diabetes population with tuberculosis and very poor glycaemic control deserves further investigation.

By using this new weekly mean glycaemia concept we can directly measure the parameter that really counts—that is, the average glucose concentrations, whereas A1C is a surrogate parameter for the evaluation of average glucose concentrations. Besides, the full effect of any implemented therapeutic strategy will only be fully reflected by A1C values 3–4 months later and the use of the weekly mean glycaemia concept allows for weekly adjustments in the therapeutic strategy, speeding up the return to normal glycaemic control within 3–4 weeks. This patient presented an A1C of 12.0% in the first visit and 6 months after her return to normal glycaemic control the A1C dropped to 7.4%. Her present total insulin daily dose was recently reduced from 170 IU/day to 140 IU/day, maintaining the 8 mg daily dose of rosiglitazone.

LEARNING POINTS

Diabetes and tuberculosis are two very serious medical conditions with reciprocal negative impact—diabetes makes tuberculosis worse, and vice versa.

Drugs used for tuberculosis treatment tend to promote a deep worsening of glycaemic control.

Diabetic patients with tuberculosis should preferably receive intensive insulin treatment in order to restore glycaemic control.

The significant response to rosiglitazone in a fully “insulinised” patient being treated for tuberculosis warrants further research.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication

REFERENCES

- 1.Rao PV. Persons With Type 2 Diabetes and Co-Morbid Active Tuberculosis Should Be Treated With Insulin. Int J Diab Dev Countries 1999; 19: 79–86 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leung CC, Lam TH, Chan WM, et al. Diabetic control and risk of tuberculosis: a cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 2008; 167: 1486–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang CS, Yang CJ, Chen HC, et al. Impact of type 2 diabetes on manifestations and treatment outcome of pulmonary tuberculosis. Epidemiol Infect 2008; June 18: 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]