Abstract

Neurotransmitter release from mammalian sensory neurons is controlled by CaV2.2 N-type calcium channels. N-type channels are a major target of neurotransmitters and drugs that inhibit calcium entry, transmitter release and nociception through their specific G protein–coupled receptors. G protein–coupled receptor inhibition of these channels is typically voltage-dependent and mediated by Gβγ, whereas N-type channels in sensory neurons are sensitive to a second G protein–coupled receptor pathway that inhibits the channel independent of voltage. Here we show that preferential inclusion in nociceptors of exon 37a in rat Cacna1b (encoding CaV2.2) creates, de novo, a C-terminal module that mediates voltage-independent inhibition. This inhibitory pathway requires tyrosine kinase activation but not Gβγ. A tyrosine encoded within exon 37a constitutes a critical part of a molecular switch controlling N-type current density and G protein–mediated voltage-independent inhibition. Our data define the molecular origins of voltage-independent inhibition of N-type channels in the pain pathway.

N-type calcium channels are located at presynaptic terminals of nociceptive neurons that synapse in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. In this location, they control release of neurotransmitter and the transmission of nociceptive information1. Furthermore, N-type channels in nociceptors possess high sensitivity to inhibition by neurotransmitters and drugs that act through G protein–coupled receptors2–4. Endogenous transmitters including enkephalins, endocannabinoids and GABA all inhibit N-type channels through their respective G protein–coupled receptors to attenuate nociception1,2,5. This inhibitory pathway has a key role in limiting transmitter release from primary sensory afferents in the dorsal horn. Morphine and other opiates co-opt this inhibitory pathway, explaining their powerful analgesic actions at the spinal level6.

The most ubiquitous form of transmitter-initiated inhibition acting on the N-type channel is fast, membrane delimited, voltage-dependent and mediated by Gβγ binding directly to the channel7–9. This form of inhibition, seen throughout the nervous system, is thought to have a key role in transmitter-mediated control of transmitter release10,11. It is especially effective at attenuating low-frequency stimuli but less effective during periods of intense activity because depolarization relieves voltage-dependent inhibition12,13. In some neurons, N-type channels also possess a sustained form of inhibition that is independent of voltage. Voltage-independent inhibition is particularly prominent and well studied in neurons of dorsal root ganglia and sympathetic ganglia. In sympathetic neurons, voltage-independent inhibition of N-type current is relatively slow and is mediated by the Gq and G11 classes of G protein and phospholipase C activation14. By contrast, in dorsal root ganglia, voltage-independent inhibition of N-type current requires protein tyrosine kinase activation15,16. The mechanisms that govern the coupling of N-type channels to specific G protein signaling pathways and the sensitivity of N-type channels to voltage-independent inhibition are unknown.

We recently discovered a splice isoform of the main α1 subunit of the N-type calcium channel. Exons 37a and 37b are a pair of mutually exclusive exons encoding two alternative 32–amino acid modules (e37a and e37b, respectively) at the C terminus of CaV2.2. The protein containing the former, CaV2.2e[37a], is notable for its enrichment in nociceptors17. Previously, we showed that substitution of e37b with e37a increases CaV2.2 current densities17 and consequently calcium entry during action-potential waveforms18. However, the physiological significance of CaV2.2e[37a] expression to nociceptor function is not completely understood.

Here we report that selective inclusion of e37a in CaV2.2 creates an inhibitory pathway that is voltage independent and that increases substantially the sensitivity of CaV2.2 channels to opiates and GABA. This pathway diverges from voltage-dependent inhibition downstream of Gi- and Go-coupled receptors and requires tyrosine kinase. We identify a tyrosine encoded within e37a and absent in e37b as essential for voltage-independent inhibition of CaV2.2e[37a] channels. Cell-specific alternative splicing of the mRNA encoding CaV2.2 thus serves as a molecular switch that controls the sensitivity of N-type channels to neurotransmitters and drugs that modulate nociception.

RESULTS

Exon 37a augments G protein–dependent inhibition

We first determined that e37a modulated the responsiveness of CaV2.2 to G proteins. We expressed CaV2.2e[37b] and CaV2.2e[37a] channels in tsA201 cells (large T-antigen–transformed HEK293 cells) together with auxiliary subunits CaVβ3 and CaVα2δ1, and we determined their sensitivity to internal GTP-γS, which globally activates G proteins (0.4 mM; Fig. 1). By carefully optimizing transfections, we minimized variability in expression (see Methods). Consistent with our previous studies, current densities produced by N-type CaV2.2e[37a] were significantly (1.8-fold; P = 0.0039 at +10 mV) larger than those produced by CaV2.2e[37b] (Fig. 1a,b)17,18. We showed that GTP-γS inhibited both CaV2.2e[37b] and CaV2.2e[37a] currents relative to their respective control currents recorded in the absence of internal GTP-γS (Fig. 1a,b). Notably, we found that the extent of GTP-γS–mediated inhibition differed greatly between splice isoforms. GTP-γS was about twice as effective on CaV2.2e[37a] currents as it was on CaV2.2e[37b] currents. It reduced peak CaV2.2e[37b] current densities on average to 63% of control levels, whereas it reduced CaV2.2e[37a] current densities to only 34% of their respective controls (Fig. 1a,b).We also noted that CaV2.2e[37b] and CaV2.2e[37a] current densities were indistinguishable from each other in the presence of internal GTP-γS. Next, we asked whether G protein activation inhibited CaV2.2e[37b] and CaV2.2e[37a] channels by the same mechanism.

Figure 1.

G protein activation differentially inhibits CaV2.2e[37b] and CaV2.2e[37a] channels. Calcium currents from cells expressing (a) CaV2.2e[37b] (e37b) and (b) CaV2.2e[37a] (e37a) channels recorded with control (con) internal solution and with 0.4 mM internal GTP-γS. Currents were evoked by test pulses alone (−pp) and preceded by a prepulse to +80 mV (+pp). In the presence of GTP-γS, prepulses to +80 mV recovered CaV2.2e[37b] currents fully (a; current densities not significantly different from control; P > 0.5). Prepulses only partially recovered inhibited CaV2.2e[37a] currents (b; current densities significantly different from control at test voltages between −5 mV and +55 mV, P < 0.05). Prepulses did not induce facilitation in the absence of internal GTP-γS. Values of n for panel a are 20 (con), 16 (−pp) and 16 (+pp). Values of n for panel b are 21 (con), 21 (−pp) and 21 (+pp). (c) Currents evoked by test pulses to +80 mV in control and in the presence of 0.4 mM internal GTP-γS. Exemplar currents are shown above average (mean ± s.e.m. throughout) current densities for each isoform. Number of cells in each dataset is indicated. CaV2.2e[37a] current densities in the presence of GTP-γS are significantly different from control (*P = 0.0024).

Voltage-dependent inhibition is the most common form of G protein–mediated modulation of CaV2.2 channels. This widely studied inhibitory pathway involves Gβγ binding to the intracellular loop between transmembrane α-helices IS6 and IIS1 (the I–II loop), as well as to other locations of the CaV2.2 subunit8,19–22. Hallmark features of voltage-dependent inhibition include (i) significantly greater inhibition of N-type currents at hyperpolarized voltages, (ii) a concomitant depolarizing shift in channel activation, (iii) relief of inhibition by strong depolarizing prepulses (facilitation) and (iv) slowing of channel activation kinetics with prolonged depolarization, reflecting slow relief of inhibition7,8,22,23. A second voltage-independent pathway also inhibits N-type currents, particularly N-type currents in sensory neurons5,24. By definition, strong depolarizing prepulses do not relieve G protein–mediated, voltage-independent inhibition. We therefore used saturating depolarizing prepulses to determine the extent of voltage-dependent and voltage-independent inhibition mediated by GTP-γS on CaV2.2e[37b] and CaV2.2e[37a] channels.

Two distinct G protein–dependent inhibitory pathways

We found evidence that a voltage-dependent pathway inhibited CaV2.2e[37b]. Depolarizing prepulses completely relieved the inhibitory effects of internal GTP-γS on CaV2.2e[37b] currents (Fig. 1a). CaV2.2e[37b] current densities that were evoked after prepulses and measured in the presence of GTP-γS were indistinguishable from control currents measured in the absence of GTP-γS. Our data imply that CaV2.2e[37b] currents are inhibited by a purely voltage-dependent mechanism (Fig. 1a). Consistent with this, we also found that outward currents through CaV2.2e[37b] channels that were induced by step depolarizations to +80 mV were resistant to the inhibitory actions of GTP-γS (Fig. 1c), as predicted for voltage-dependent inhibition.

A similar voltage-dependent inhibitory mechanism also acted on CaV2.2e[37a] channel currents, but we observed that GTP-γS induced an additional component of inhibition that persisted even after prepulses to +80 mV (Fig. 1b,c). CaV2.2e[37a] current densities measured in the presence of GTP-γS but after a prepulse were significantly reduced as compared with control recordings (Fig. 1b; P = 0.0007 at +10 mV). Similarly, outward currents through CaV2.2e[37a] channels induced by step depolarizations to +80 mV recorded in the presence of GTP-γS were significantly smaller than currents recorded in the absence of GTP-γS (Fig. 1c; P = 0.0024). Under the same conditions as described above, outward CaV2.2e[37b] current densities measured at +80 mV were unaffected by GTP-γS (P = 0.5629). Our data are consistent with the hypothesis that a second, G protein–dependent, voltage-independent inhibitory pathway couples to CaV2.2e[37a] channels.

To confirm that our prepulse protocols completely reversed all voltage-dependent inhibition in both isoforms, we compared channel activation curves from normalized tail currents generated from control recordings with those recorded in the presence of GTP-γS with and without prepulses to +80 mV (Fig. 2a,b). GTP-γS induced depolarizing right shifts in channel-activation curves from both isoforms, a hallmark of voltage-dependent inhibition7,8,12. In the continued presence of GTP-γS, depolarizing prepulses shifted channel-activation curves of both isoforms back to control values (Fig. 2a,b). Notably, the voltage dependence of CaV2.2e[37a] channel activation in the presence of GTP-γS was indistinguishable from that under control conditions if recorded immediately after a prepulse, even though current density levels recovered to only 50% of control values (Fig. 1b). We fit individual data sets with the sum of two Boltzmann functions, with parameters V11/2 and V21/2 being the activation midpoints (mV) and A1 and A2 the normalized amplitudes for each Boltzmann function. Average parameters (mean ± s.e.m.) for CaV2.2e[37b] in the absence (n = 4) and in the presence of GTP-γS without (n = 5) and with (n = 5) prepulse were, for V11/2, 2.68 ± 0.64 mV, 3.00 ± 1.09 mV and 3.31 ± 0.75 mV; for A1, 0.49 ± 0.03, 0.14 ± 0.08 and 0.53 ± 0.05; for V21/2, 28.43 ± 1.09 mV, 27.34 ± 1.48 mV and 25.69 ± 2.63 mV; for A2, 0.55 ± 0.03, 0.89 ± 0.09 and 0.50 ± 0.05. Average parameters for CaV2.2e[37a] in the absence (n = 6) and in the presence of GTP-γS without (n = 3) and with (n = 3) prepulse were, for V11/2, −0.47 ± 0.86 mV, −4.42 ± 1.00 mV and 0.24 ± 2.03 mV; for A1, 0.49 ± 0.01, 0.02 ± 0.03 and 0.54 ± 0.06; for V21/2, 23.17 ± 0.71 mV, 27.15 ± 2.40 mV and 23.09 ± 2.32 mV; for A2, 0.53 ± 0.01, 1.03 ± 0.02 and 0.49 ± 0.06. The normalizing effect of prepulses on channel activation kinetics in the presence of GTP-γS is also apparent in the current-voltage relationships in Figure 1a,b.

Figure 2.

Prepulse relieves voltage-dependent inhibition fully. Averaged, normalized activation curves generated from tail currents recorded at −60 mV in cells expressing (a) CaV2.2e[37b] and (b) CaV2.2e[37a] channels in the absence (con; n = 4 and 6) and presence of GTP-γS without (−pp; n = 5 and 3) and with (+pp; n = 5 and 3) prepulse. Recording conditions are the same as in Figure 1. Activation curves only reflect data from recordings with rapid settling times that permit accurate resolution of calcium channel tail currents. The sum of two Boltzmann functions fit individual datasets20. Insets in a show examples of tail currents evoked by a hyperpolarizing step to −60 mV from a test depolarization to +10 mV. Amplitudes are normalized to peak current.

These data showed that the prepulse protocol used in our studies fully reversed voltage-dependent inhibition. Thus, a voltage-dependent pathway inhibits CaV2.2e[37b] channels. However, both voltage-dependent and voltage-independent pathways inhibit CaV2.2e[37a] channels. Notably, in the presence of GTP-γS, average CaV2.2e[37b] and CaV2.2e[37a] current densities were indistinguishable when evoked either with or without prepulses (Fig. 1a,b).

μ-opioid and GABAB receptors use both inhibitory pathways

Our studies using internal GTP-γS suggested that e37a created a voltage-independent inhibitory pathway affecting the N-type channel that was not present when e37b replaced e37a. To determine the functional relevance of this pathway, we coexpressed CaV2.2e[37b] or CaV2.2e[37a] channels with the μ-opioid receptor as well as with the heteromeric GABAB receptor (GABABR1a and GABABR2 subunits) in tsA201 cells. These G protein–coupled receptors are important in regulating N-type channel activity and transmitter release from sensory neurons. We initially used the perforated-patch recording method to avoid cell dialysis and minimize disruption of G protein–coupled receptor signaling pathways. Later, we reached the same conclusions using standard whole-cell recording (as discussed below).

We used 50 µM baclofen to activate the GABAB receptor, and we limited agonist exposure to avoid receptor desensitization16,25. Baclofen induced rapid and reversible inhibition of both CaV2.2e[37b] and CaV2.2e[37a] currents (Fig. 3a,b). N-type current densities transiently rebounded to values greater than those in the control immediately after removing baclofen, as documented by others26. GABAB receptor activation inhibited CaV2.2e[37b] and CaV2.2e[37a] current densities to 61% (n = 11; P < 0.0001) and 45% (n = 10; P < 0.0001) of control values, respectively. Prepulses to +80 mV reversed the effects of baclofen on CaV2.2e[37b] current densities completely (107% of control; n = 11, P = 0.502; Fig. 3c,d) whereas the same prepulses only partially reversed the inhibitory effects of baclofen on CaV2.2e[37a] current densities (69% of control; n = 10, P < 0.0001; Fig. 3e,f). Consistent with our studies using GTP-γS, inhibition of CaV2.2e[37b] channels by GABAB receptor was exclusively voltage-dependent, but inhibition of CaV2.2e[37a] channels was mediated by both voltage-dependent and voltage-independent mechanisms.

Figure 3.

Differential inhibition of CaV2.2e[37b] and CaV2.2e[37a] channels by GABAB receptor activation. (a–f) Calcium currents recorded using the perforated-patch technique from cells expressing CaV2.2e[37b] channels (a,c,d; n = 11) and CaV2.2e[37a] channels (b,e,f; n = 10) together with GABABR1a and GABABR2 subunits. Peak currents evoked by test pulses to 0 mV recorded from representative cells expressing CaV2.2e[37b] (a) and CaV2.2e[37a] (b) illustrate the time course of inhibition mediated by 50 µM baclofen. Exemplar CaV2.2e[37b] (c) and CaV2.2e[37a] (e) currents together with average, peak current densities as a percentage of control (d,f) recorded in the absence (con) and presence of baclofen without (−pp) and with (+pp) a prepulse to +80 mV. In f, the prepulse is only partially effective at recovering CaV2.2e[37a] current inhibited by baclofen (*significantly different from 100%; P < 0.0001).

We obtained very similar results in cells coexpressing the μ-opioid receptor using 10 µM [d-Ala2,N-methyl-Phe4,Gly5-ol]-enkephalin (DAMGO) as the agonist (Fig. 4). Inhibition of CaV2.2e[37b] currents was primarily voltage dependent, as indicated by nearly complete recovery of receptor-mediated inhibition by a prepulses to +80 mV (92% of control; Fig. 4c,d). By contrast, μ-opioid receptor activation was coupled to both voltage-dependent and voltage-independent inhibition of CaV2.2e[37a] currents. Here, prepulses led to only partial recovery of CaV2.2e[37a] currents in the presence of DAMGO (Fig. 4e,f). DAMGO inhibition of CaV2.2e[37a] currents also featured an initial fast block (<10 s, followed by a slower inhibitory phase (100 s; Fig. 4b; see also Supplementary Fig. 1 online). By comparison, DAMGO inhibited CaV2.2e[37b] currents rapidly (Fig. 4a; see also Supplementary Fig. 1). Both isoforms recovered slowly from μ-opioid receptor–dependent inhibition, and complete reversal took >100 s after agonist removal (Fig. 4a,b).We do not know the significance of this biphasic onset of inhibition mediated by DAMGO, which was only seen in cells expressing CaV2.2e[37a], not CaV2.2e[37b].

Figure 4.

Differential inhibition of CaV2.2e[37b] and CaV2.2e[37a] channels by μ-opioid receptor activation. (a–f) Calcium currents recorded using the perforated-patch technique from cells expressing CaV2.2e[37b] channels (a,c,d; n = 10) and CaV2.2e[37a] channels (b,e,f; n = 6) together with μ-opioid receptor. Peak currents evoked by test pulses to 0 mV recorded from representative cells expressing CaV2.2e[37b] (a) and CaV2.2e[37a] (b) illustrate the time course of inhibition mediated by 10 µM DAMGO. Exemplar CaV2.2e[37b] (c) and CaV2.2e[37a] (e) currents together with average, peak currents as a percentage of control (d,f) recorded in the absence (con) and presence of DAMGO without (−pp) and with (+pp) a prepulse to +80 mV. Significant CaV2.2e[37a] current remains inhibited by DAMGO when evoked by test potentials preceded with a step to +80 mV (f) (*significantly different from 100%; P < 0.0001).

Our data show that G protein activation inhibits both CaV2.2e[37b] and CaV2.2e[37a] channels by a voltage-dependent pathway. However, sequences unique to e37a create a second G protein–dependent inhibitory domain on CaV2.2e[37a] channels allowing G protein receptor activation to suppress N-type currents through an additional voltage-independent pathway.

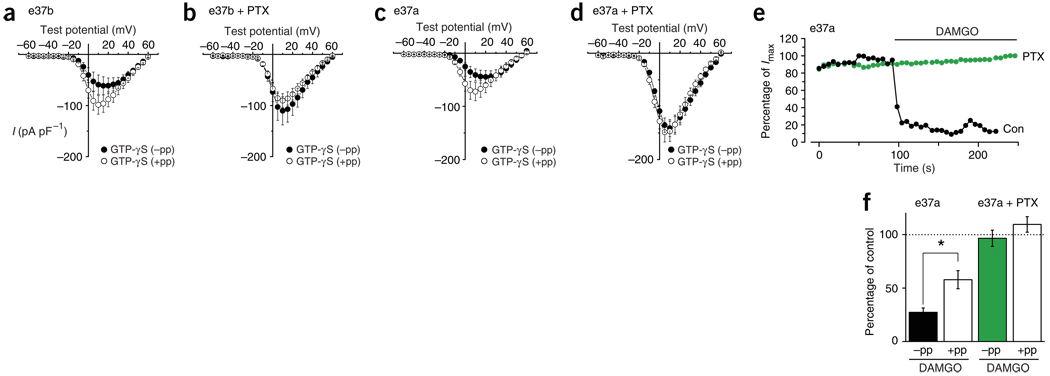

Pertussis toxin occludes both inhibitory pathways

Gβγ dimer released from activated pertussis toxin (PTX)-sensitive Gi and Go proteins mediates voltage-dependent inhibition of native N-type currents in sensory neurons16,27. We next confirmed that this same signaling pathway mediates voltage-dependent inhibition of CaV2.2e[37b] and CaV2.2e[37a] isoforms when activated by GTP-γS or receptor stimulation (Fig. 5). CaV2.2e[37b] currents recorded from cells pretreated with PTX were insensitive to internal GTP-γS; currents showed no facilitation in response to a prepulse (Fig. 5a,b). Notably, CaV2.2e[37a] currents recorded from cells pretreated with PTX were also insensitive to internal GTP-γS, as neither voltage-dependent nor voltage-independent inhibition was observed (Fig. 5c,d). CaV2.2e[37a] currents recorded in the presence of GTP-γS not only lacked prepulse facilitation but were twice as large in cells pretreated with PTX (Fig. 5c,d).

Figure 5.

PTX-sensitive G proteins mediate inhibition of CaV2.2 isoforms. (a,b) CaV2.2 e[37b]) and (c,d) CaV2.2e[37a] currents recorded with internal GTP-γS from untreated cells (a,c) and cells pretreated with PTX (500 ng ml−1 for 16 h) (b,d) without (−pp) and with (+pp) a prepulse to +80 mV. a, n = 7; b, n = 6; c, n = 7; d, n = 7. CaV2.2e[37a] current densities were significantly greater after PTX pretreatment than those in untreated cells (P = 0.0154, +10 mV, +pp). (e,f) CaV2.2e[37a] currents in cells coexpressing the μ-opioid receptor. Recordings without and with prepulse to +80 mV are compared in untreated (n = 7) and PTX-treated (n = 7) cells. (e) Representative time course of current amplitude as a percentage of current before exposure to 10 µM DAMGO of CaV2.2e[37a] currents from an untreated cell (con) and one preincubated with PTX. DAMGO inhibited currents in untreated cells, and currents were significantly greater after prepulse (*P = 0.007). (f) Average CaV2.2e[37a] currents in the presence of 10 µM DAMGO expressed as a percentage of control currents. DAMGO had no effect on currents in cells pretreated with PTX (not significantly different from 100%; P = 0.66 without prepulse and P = 0.23 with prepulse).

Furthermore, PTX occluded both of the inhibitory pathways to CaV2.2e[37a] channels in cells coexpressing μ-opioid receptor and challenged with DAMGO (Fig. 5e,f). Our data thus show that a common class of Gi and Go protein couples to CaV2.2e[37b] and CaV2.2e[37a] channels to mediate both voltage-dependent and voltage-independent inhibition.

Distinct signaling pathways mediate inhibition

Voltage-dependent inhibition of native N-type currents is likely to involve direct binding of Gβγ. We therefore used a Gβγ buffer to assess the effectiveness of G protein stimulation on CaV2.2 isoforms. We expressed a myristoylated C-terminal Gβγ-binding domain of the G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (MAS-GRK2-ct). This protein fragment buffers Gβγ and occludes voltage-dependent inhibition of native N-type currents28. CaV2.2e[37b] currents in cells expressing MAS-GRK2-ct were completely insensitive to G protein stimulation by internal GTP-γS (Fig. 6a–c). We observed no significant difference between control CaV2.2e[37b] current densities and those recorded with internal GTP-γS (P = 0.7632 at 0 mV), consistent with previous reports that Gβγ is essential for voltage-dependent inhibition of N-type currents8. MAS-GRK2-ct also occluded voltage-dependent inhibition of CaV2.2e[37a] currents, as illustrated by the lack of prepulse facilitation in cells stimulated by internal GTP-γS (Fig. 6d–f). However, voltage-independent inhibition of CaV2.2e[37a] channels by internal GTP-γS was intact and unaffected by MAS-GRK2-ct (Fig. 6d–f). CaV2.2e[37a] currents recorded in the presence of internal GTP-γS were significantly inhibited as compared with control (P = 0.0068 at 0 mV). Thus, voltage-dependent inhibition of CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b] channels uses a Gβγ-dependent signaling pathway. By contrast, an additional Gβγ-independent, Gi- and Go-dependent pathway couples to CaV2.2e[37a] channels to mediate voltage-independent inhibition.

Figure 6.

Voltage-dependent but not voltage-independent inhibition requires Gβγ. Average current-voltage relationships for currents recorded in cells expressing MAS-GRK2-ct (ref. 28) together with (a,b,c) CaV2.2e[37b] and (d,e,f) CaV2.2e[37a] in the absence (a,d) and presence (b,e) of GTP-γS (0.4 mM). Average (c) CaV2.2e[37b] and (f) CaV2.2e[37a] current densities recorded at 0 mV. CaV2.2e[37b] currents recorded with internal GTP-γS were not significantly different (NS) from control currents at all potentials with (+pp) or without (−pp) prepulse. CaV2.2e[37a] currents recorded in cells expressing MAS-GRK2-ct were inhibited by internal GTP-γS (f; *P = 0.00678), but inhibition was unaffected by a prepulse. For a, n = 10; b, n = 10; c, n = 11 and n = 10 (GTP-γS); d, n = 10; e, n = 10; f, n = 11 and n = 12 (GTP-γS).

Non-receptor tyrosine kinases mediate a number of neuronal functions. Of special significance here, research in chick sensory neurons implicates src tyrosine kinases in voltage-independent inhibition of native N-type currents triggered by G protein–coupled receptors29. Furthermore, nerve terminals are enriched in pp60c-src tyrosine kinase30,31. We therefore used a selective peptide inhibitor of pp60c-src tyrosine kinase to test for its involvement inG protein–mediated inhibition of CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b] channels. We observed no significant effect of the pp60c-src peptide on GTP-γS–mediated inhibition of CaV2.2e[37b] currents; voltage-dependent inhibition remained intact (Fig. 7a,b). This was supported by the presence of robust prepulse facilitation of CaV2.2e[37b] in recordings obtained in the presence of internal GTP-γS (P = 0.0304 in the presence of pp60 peptide compared with and without prepulse, n = 8 for each data set).We also found no effect of pp60c-src peptide on voltage-dependent inhibition of CaV2.2e[37a] currents, as illustrated by the presence of robust prepulse facilitation in cells stimulated by internal GTP-γS (Fig. 7c,d).However, the pp60c-src peptide did prevent internal GTP-γS from inducing voltage-independent inhibition of CaV2.2e[37a] channels (Fig. 7c,d). These data are consistent with the hypothesis that voltage-independent inhibition is absent when pp60c-src tyrosine kinase is inhibited. Voltage-independent inhibition of N-type current mediated by activation of μ-opioid receptor (Fig. 7e–h) and GABAB receptor (see Supplementary Fig. 2 online) was also selectively occluded by the pp60c-src inhibitory peptide. CaV2.2e[37b] and CaV2.2e[37a] currents in cells coexpressing μ-opioid receptor showed robust voltage-dependent inhibition in response to DAMGO, independent of the presence of the pp60c-src peptide (Fig. 7e,f). By contrast, the pp60c-src peptide reduced significantly receptor-mediated voltage-independent inhibition of CaV2.2e[37a] channels (Fig. 7g,h). Parameters from Boltzmann linear fits of current-voltage relationships are in Supplementary Table 1 online. Voltage-dependent inhibition of CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b] channels thus occurs independent of src tyrosine kinase. But voltage-independent inhibition is a feature unique to CaV2.2e[37a] channels dependent on src tyrosine kinase.

Figure 7.

pp60c-src tyrosine kinase peptide inhibitor prevents voltage-independent inhibition. (a–d) Averaged, peak current voltage-relationships from cells expressing CaV2.2e[37b] (a, n = 7; b, n = 8) and CaV2.2e[37a] (c, n = 9; d, n = 10) in the presence of 0.4 mM internal GTP-γS with (+pp) and without (−pp) prepulses to +80 mV. Currents recorded from cells without (a,c) and with (b,d) 70 µM pp60c-src peptide inhibitor (pp60c-src) in the pipette. CaV2.2e[37b] currents with and without pp60c-src peptide are not significantly different at any test potential (P > 0.05). Control CaV2.2e[37a] currents (c) compared with recordings with 70 µM pp60c-src peptide (d) are significantly different at test potentials between −20 mV and +55 mV in presence or absence of the prepulse (P < 0.05). (e–h) Average peak current density values at 0 mV from cells expressing μ-opioid receptor together with CaV2.2e[37b] (e,f) and CaV2.2e[37a] (g,h). Currents recorded using standard whole-cell method without (−pp) and with (+pp) prepulses to +80 mV in the absence (con) and presence of DAMGO with and without pp60c-src tyrosine kinase peptide inhibitor. CaV2.2e[37a] currents recorded in the presence of DAMGO remained significantly inhibited after a prepulse compared with control (g, *P = 0.0076; voltage-independent inhibition), but the peptide inhibitor prevented this form of inhibition (h, not significant (NS)). For e, n = 7; f, n = 7; g, n = 10; h, n = 10. Exemplar current traces are shown above bar graphs.

Voltage-independent inhibition requires tyrosine 1747

Our data showed that voltage-independent inhibition of CaV2.2e[37a] currents required pp60c-src tyrosine kinase. Which amino acids unique to e37a mediate voltage-independent inhibition? Fourteen out of 32 amino acids differ between e37a and e37b. These differences include two consensus sites for tyrosine kinase phosphorylation at positions Y1743 and Y1747 (as numbered in GenBank sequence AF055477) in e37a but not in e37b (Fig. 8a). Y1743 is present in e37b, but lacks a neighboring lysine (K1744) that renders Y1743 in e37a a potential substrate for tyrosine kinases. By contrast, phenylalanine replaces tyrosine at position 1747 in e37b. Therefore, we generated two CaV2.2e[37a] tyrosine mutants, CaV2.2e[37a]Y1743F and CaV2.2e[37a]Y1747F, to test each tyrosine’s contribution to GTP-γS–mediated inhibition. Both mutant channels expressed equally well and were inhibited by internal GTP-γS (Fig. 8b,c). GTP-γS–mediated inhibition of CaV2.2e[37a]Y1743F mutant channels was indistinguishable from that of wild-type CaV2.2e[37a] channels. CaV2.2e[37a]Y1743F showed both voltage-dependent and voltage-independent inhibition (Fig. 8b). By marked contrast, the properties of the CaV2.2e[37a]Y1747F mutant were significantly different from wild-type CaV2.2e[37d] (P = 0.0192) and were indistinguishable from those of wild-type CaV2.2e[37b] channels (Fig. 8c). GTP-γS–mediated inhibition of CaV2.2e[37a]Y1747F was exclusively voltage-dependent; it was completely relieved by prepulses to +80 mV. We found no evidence for voltage-independent inhibition of CaV2.2e[37a]Y1747F. Furthermore, CaV2.2e[37a]Y1747F current densities were significantly reduced compared with wild-type CaV2.2e[37a] (Fig. 1b; P < 0.05 over a range of voltages) but indistinguishable from wild-type CaV2.2e[37b] (Fig. 1a). Parameters from Boltzmann linear fits of current voltage relationships are in Supplementary Table 1. Effectively, the Y1747F mutation converts the e37a phenotype to that of e37b. These data identify Y1747 in CaV2.2e[37a] as a control point that sets overall current density levels and renders the CaV2.2 channel permissive to G protein–mediated, voltage-independent inhibition.

Figure 8.

Conservation of exon 37a and essential role of Y1747 in voltage-independent inhibition. (a) Amino acid sequence alignments for exons e37a and e37b of human, chimpanzee (chimp), macaque, dog, rat, mouse and chicken CaV2.2 genes. Arrows highlight two tyrosine kinase consensus sites at positions 1743 and 1747 in rat e37a. Bold font indicates 100% conservation across species. The sequence encoding the first amino acid of chimpanzee e37b was located close to a gap in the chimpanzee genome sequence. (b,c) Averaged peak current-voltage relationships from cells expressing CaV2.2e[37a]Y1743F mutant channels (b) and CaV2.2e[37a]Y1747F mutant channels (c) with control internal solution (con, n = 9 and n = 10) and with GTP-γS–containing internal solution without (−pp; n = 7 and n = 8) and with (+pp; n = 7 and n = 8) prepulses to +80 mV. Upper panels show exemplar currents evoked at +10 mV for each dataset. The prepulse did not fully relieve GTP-γS inhibition of CaV2.2e[37a] Y1743F current densities, which were significantly different from control at test pulses between −15 mV and +35 mV (P < 0.05). The prepulse relieved GTP-γS inhibition of CaV2.2e[37a] Y1747F completely. Control CaV2.2e[37a]Y1747F current densities were not significantly different from GTP-γS recordings with prepulses.

Our data implicate cell-specific expression of CaV2.2e[37a] in controlling the pharmacological sensitivity of N-type channels in nociceptors. Notably, the presence or absence of e37a modulates the inhibitory actions of neurotransmitters and drug on N-type channels by way of their respective G protein–coupled receptors. These results offer a molecular explanation for the high sensitivity of native N-type channels in sensory neurons to inhibition by opioid and GABAB receptor activation4,24.

DISCUSSION

The majority of neural genes are subject to alternative splicing, but few studies attribute cell-specific inclusion of a particular exon to a particular process in an identified population of neurons. Here, we uncover the function of exon 37a, the isoform containing which is highly expressed in nociceptors17. Exon 37a creates a module in the C terminus of CaV2.2 that controls the extent and type of inhibition that can be mediated by G protein receptor activation. GABA, opiates and probably other transmitters and drugs can utilize this pathway to inhibit CaV2.2 channels by a mechanism that is independent of stimulus intensity. Our results reveal the molecular process underlying this important feature of CaV2.2 channels in sensory neurons24.

Cell-specific enrichment of e37a in nociceptors is likely to have evolved to enable inhibition of nociceptive transmission under periods of intense neuronal activity13,32. Available genome sequences indicate that exons equivalent to e37a and e37b are highly conserved in rat, mouse, human, chimpanzee, macaque and dog, indicating that alternative splicing at the e37a and e37b site may confer functional advantage to these organisms (Fig. 8a). In all these species, e37a contains a tyrosine codon analogous to rat Y1747 in CaV2.2, which e37b replaces with a codon for phenylalanine. The chicken gene encoding CaV2.2 is of special interest because it contains only one exon in this region of the gene and has a sequence similar, but not identical, to mammalian e37a. Notably, this single exon in chicken CaV2.2 contains a tyrosine equivalent to Y1747. Consistent with our data, all sensory neurons in the chick show both voltage-dependent and voltage-independent inhibition after G protein activation24.

The N-type channel is the target of numerous G protein–coupled neurotransmitter receptors at a variety of synapses. Consequently, its presence permits neurotransmitters and drugs to modulate transmitter release. In all neurons, CaV2.2 channels are inhibited by means of a G protein–dependent voltage-dependent pathway, mediated by direct interaction of Gβγ subunit dimers with the CaV2.2 subunit, probably by way of the I–II intracellular loop10,15. This pathway is common to both CaV2.2 isoforms studied here and may be a feature of all CaV2.2 isoforms. By contrast, voltage-independent inhibition is observed in select cell types and is a prominent feature of N-type channels in sensory and also in sympathetic neurons24,28. Sensory neurons express e37a-containing CaV2.2 channels, which are present at low abundances elsewhere in the nervous system. Here, we show that e37a inclusion is the molecular basis of voltage-independent inhibition of N-type currents in these cells. Notably, PTX completely occluded GTP-γS–mediated inhibition of CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b] isoforms in tsA201 cells, consistent with exclusive coupling of these isoforms to the Gi and Go classes of G protein. However, other G proteins, particularly Gq and G11 classes, mediate inhibition of N-type channels in sympathetic neurons through phospholipase C activation14,28. It is therefore possible that other sites of alternative splicing in CaV2.2 regulate coupling to Gq and G11 signaling pathways.

By studying naturally occurring CaV2.2 splice isoforms, we have established that voltage-dependent and voltage-independent inhibition utilize functionally and molecularly separable pathways24. The two inhibitory pathways utilize the same receptors and PTX-sensitive Gi and Go classes of G protein, but diverge downstream of the trimeric G protein. Voltage-dependent inhibition requires Gβγ, which binds directly to CaV2.2 and is independent of pp60c-src tyrosine kinase. We found the characteristics of voltage-dependent inhibition mediated by G protein activation indistinguishable between isoforms, consistent with the involvement of CaV2.2 domains outside of the e37a and e37b region. In contrast, voltage-independent inhibition was unique to the CaV2.2e[37a] isoform, independent of Gβγ, dependent on pp60c-src tyrosine kinase, and in particular required tyrosine at position 1747 in the C terminus. Y1747 may be the site of src tyrosine kinase–mediated phosphorylation that underlies voltage-independent inhibition of CaV2.2 channels in sensory neurons, but it remains possible that other residues are targets of this kinase.

Our studies of CaV2.2e[37a] agree with several reports implicating kinase-dependent phosphorylation in voltage-independent inhibition of N-type currents in sensory neurons. However, the nature of the kinase implicated and the time course of inhibition of the N-type current differ with the type of G protein–coupled receptor16,33,34. Notably, src tyrosine kinase has been shown to form a complex with the CaV2.2 subunit of rat hippocampal and chick dorsal root ganglia neurons. Furthermore, rapid, reversible, GABAB-dependent and voltage-independent inhibition of CaV2.2 channels in chick sensory neurons uses src tyrosine kinase16,35,36. In addition, G protein–mediated, voltage-independent inhibition of CaV2.2 channels in sensory neurons controls channel internalization and removal from the plasma membrane33,35,37. It will therefore be interesting to determine whether e37a confers inhibition of current through channel internalization. The critical Y1747 we identify in e37a is part of an internalization motif (YXLL; Fig. 8). Evidence suggests that this motif participates in rapid, clathrin-dependent internalization of a large number of membrane proteins, including the NR2B subunit of the NMDA receptor38,39. Our results demonstrate Y1747 as essential for mediating voltage-independent inhibition, but they do not exclude involvement of other amino acids unique to e37a.

In summary, by studying evolutionarily conserved natural variants of CaV2.2, we uncovered a critical domain in N-type channels of sensory neurons that makes these channels more sensitive to neurotransmitters and drugs. Cell-specific inclusion of e37a in CaV2.2 acts as a molecular switch linking G protein–coupled receptors to voltage-independent inhibition of the N-type calcium channel. Functionally, voltage-independent inhibition in nociceptors allows for downregulation of N-type channel activity by way of G protein–coupled receptors even during periods of intense neuronal activity.

METHODS

Transient expression of CaV2.2 calcium channels in tsA201 cell line

We expressed rat-derived cDNAs encoding calcium-channel isoforms CaV2.2e[37a] (ref. 17) and CaV2.2e[37b] (ref. 40) together with CaVβ3, CaVα2δ1 (ref. 41) and enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP; BD Bioscience) in tsA201 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) as we described previously42. We also expressed cDNAs encoding the myristoylated C-terminal Gβγ binding domain of the G protein–coupled receptor kinase MAS-GRK2-ct (ref. 28), the receptors GABABR1a and GABABR2, and the μ-opioid receptor (see Acknowledgments). Single point mutants of CaV2.2e[37a] Y1743F and Y1747F were generated using the Quik-Change Plus mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). We carefully minimized variability in expression efficiency among transfections and recording days. We only transfected cells at 70% confluence, controlled cDNA concentrations and harvested all cells exactly 24 h after transfection for recording. Cells were maintained at 4 °C in DMEM on the day of recording until needed.

Electrophysiology

We performed standard whole-cell patch clamp recording as described previously42. The external solution for all recordings contained 1 mM CaCl2, 4 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 135 mM choline chloride, pH adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH. Internal control solution for standard whole-cell recording contained 126 mM CsCl, 10 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM HEPES, 4 mM Mg-ATP, pH 7.2 with CsOH. Note that our standard control solution excludes internal GTP. We found that even relatively low concentrations of internal GTP (50 µM) induced tonic, agonist-independent, voltage-independent inhibition of N-type currents in cells coexpressing G protein–coupled receptors and CaV2.2 subunits.

We used the perforated-patch recording methods in Figures 3 and 4 to assess the inhibitory effects of μ-opioid and GABAB receptor activation, essentially as described previously17. Perforated-patch pipette internal solution contained 135 mM CsCl, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 4 mM MgCl2 and 1.2 mg ml−1 amphotericin B (Sigma-Aldrich), pH adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH. We applied agonist- and antagonist-containing solutions using a microperfusion system that reduced dead time to within 1 s (ref. 41). Recording electrodes had resistances of 2–4 MΩ when filled with internal solution and were coated with Sylgard (Dow Corning) to reduce capacitance. Series resistances (<6 MΩ for whole-cell recording and <10 MΩ for perforated-patch recording) were compensated 70–80% with a 10-µs lag time. We evoked calcium currents by voltage steps and leak-subtracted currents online using a P/−4 protocol. Data were sampled at 20 kHz and filtered at 10 kHz (−3 dB) using pClamp V8.1 software and the Axopatch 200A amplifier (Molecular Devices). Tail currents were sampled at 100 kHz. All recordings were obtained at room temperature (22–25 °C). Cells were typically held at −100 mV to remove closed-state inactivation42. Test potentials 20–25 ms in duration were applied every 6 s. Prepulses to +80 mV were 20 ms in duration and applied 10 ms before the test pulse. Prepulses maximally relieved voltage-dependent inhibition mediated by 0.4 mM internal GTP-γS. We used the following compounds: GTP-γS (Sigma-Aldrich), baclofen (Sigma-Aldrich), DAMGO (Sigma-Aldrich), PTX (Sigma-Aldrich) and pp60c-src peptide (521–533) corresponding to its C-terminal regulatory domain (Tocris). The peptide binds pp60c-src at the SH2 domain, suppressing its tyrosine kinase activity43. All average values in figures and in text are mean ± s.e.m. We used one- or two-tailed t-tests for all statistical analyses.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to S. Denome for technical assistance, K. Dunlap (Tufts University) for GABABR1a and GABABR2 cDNA clones, L. Devi (New York University) for the μ-opioid receptor cDNA clone and S.R. Ikeda (US National Institutes of Health) for the MAS-GRK-ct cDNA clone. This work was supported by US National Institutes of Health grants NS29967 and NS55251 (D.L.).

Footnotes

Accession numbers. Cacna1b encoding CaV2.2e[37a], AY211499 (ref. 17); Cacna1b encoding CaV2.2e[37b], AF055477 (ref. 40); Cacnb3 encoding CaVβ3, sequence same as M88751; Cacna2d1 encoding CaVα2δ1, AF286488 (ref. 41).

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Neuroscience website.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to writing the manuscript. D.L. directed the project. J.R. performed experiments and analyses for all figures. A.J.C. originally identified the tyrosine kinase sites in e37a, contributed to the design and construction of the tyrosine mutants, and performed the sequence analysis in Figure 8a.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://npg.nature.com/reprintsandpermissions

References

- 1.Bourinet E, Zamponi GW. Voltage gated calcium channels as targets for analgesics. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2005;5:539–546. doi: 10.2174/1568026054367610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunlap K, Fischbach GD. Neurotransmitters decrease the calcium conductance activated by depolarization of embryonic chick sensory neurones. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 1981;317:519–535. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holz GG, IV, Rane SG, Dunlap K. GTP-binding proteins mediate transmitter inhibition of voltage-dependent calcium channels. Nature. 1986;319:670–672. doi: 10.1038/319670a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taddese A, Nah SY, McCleskey EW. Selective opioid inhibition of small nociceptive neurons. Science. 1995;270:1366–1369. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polo-Parada L, Pilar G. κ- and μ-opioids reverse the somatostatin inhibition of Ca2+ currents in ciliary and dorsal root ganglion neurons. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:5213–5227. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05213.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ossipov MH, Lai J, Malan TP, Jr, Porreca F. Spinal and supraspinal mechanisms of neuropathic pain. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2000;909:12–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bean BP. Neurotransmitter inhibition of neuronal calcium currents by changes in channel voltage dependence. Nature. 1989;340:153–156. doi: 10.1038/340153a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ikeda SR. Voltage-dependent modulation of N-type calcium channels by G-protein βγ subunits. Nature. 1996;380:255–258. doi: 10.1038/380255a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herlitze S, et al. Modulation of Ca2+ channels by G-protein βγ subunits. Nature. 1996;380:258–262. doi: 10.1038/380258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikeda SR, Dunlap K. Voltage-dependent modulation of N-type calcium channels: role of G protein subunits. Adv. Second Messenger Phosphoprotein Res. 1999;33:131–151. doi: 10.1016/s1040-7952(99)80008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diverse-Pierluissi M, Dunlap K. Distinct, convergent second messenger pathways modulate neuronal calcium currents. Neuron. 1993;10:753–760. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90175-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elmslie KS. Neurotransmitter modulation of neuronal calcium channels. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2003;35:477–489. doi: 10.1023/b:jobb.0000008021.55853.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park D, Dunlap K. Dynamic regulation of calcium influx by G-proteins, action potential waveform, and neuronal firing frequency. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:6757–6766. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-17-06757.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delmas P, Coste B, Gamper N, Shapiro MS. Phosphoinositide lipid second messengers: new paradigms for calcium channel modulation. Neuron. 2005;47:179–182. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strock J, Diverse-Pierluissi MA. Ca2+ channels as integrators of G protein-mediated signaling in neurons. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004;66:1071–1076. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.002261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diverse-Pierluissi M, Remmers AE, Neubig RR, Dunlap K. Novel form of crosstalk between G protein and tyrosine kinase pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:5417–5421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bell TJ, Thaler C, Castiglioni AJ, Helton TD, Lipscombe D. Cell-specific alternative splicing increases calcium channel current density in the pain pathway. Neuron. 2004;41:127–138. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00801-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castiglioni AJ, Raingo J, Lipscombe D. Alternative splicing in the C-terminus of CaV2.2 controls expression and gating of N-type calcium channels. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 2006;576:119–134. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.115030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li B, Zhong H, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Functional role of a C-terminal Gβγ-binding domain of Cav2.2 channels. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004;66:761–769. doi: 10.1124/mol.66.3.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamid J, et al. Identification of an integration center for cross-talk between protein kinase C and G protein modulation of N-type calcium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:6195–6202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qin N, Platano D, Olcese R, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L. Direct interaction of Gβγ with a C-terminal Gβγ-binding domain of the Ca2+ channel α1 subunit is responsible for channel inhibition by G protein-coupled receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:8866–8871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hille B, et al. Multiple G-protein-coupled pathways inhibit N-type Ca channels of neurons. Life Sci. 1995;56:989–992. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)00038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elmslie KS, Zhou W, Jones SW. LHRH and GTP-γ-S modify calcium current activation in bullfrog sympathetic neurons. Neuron. 1990;5:75–80. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90035-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luebke JI, Dunlap K. Sensory neuron N-type calcium currents are inhibited by both voltage-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Pflugers Arch. 1994;428:499–507. doi: 10.1007/BF00374571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diverse-Pierluissi M, Inglese J, Stoffel RH, Lefkowitz RJ, Dunlap K. G protein-coupled receptor kinase mediates desensitization of norepinephrine-induced Ca2+ channel inhibition. Neuron. 1996;16:579–585. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujikawa S, Motomura H, Ito Y, Ogata N. GABAB-mediated upregulation of the high-voltage-activated Ca2+ channels in rat dorsal root ganglia. Pflugers Arch. 1997;434:84–90. doi: 10.1007/s004240050366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diverse-Pierluissi M, Goldsmith PK, Dunlap K. Transmitter-mediated inhibition of N-type calcium channels in sensory neurons involves multiple GTP-binding proteins and subunits. Neuron. 1995;14:191–200. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90254-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kammermeier PJ, Ikeda SR. Expression of RGS2 alters the coupling of metabotropic glutamate receptor 1a to M-type K+ and N-type Ca2+ channels. Neuron. 1999;22:819–829. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80740-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richman RW, Diverse-Pierluissi MA. Mapping of RGS12-Cav2.2 channel interaction. Methods Enzymol. 2004;390:224–239. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)90015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brugge JS, et al. Neurones express high levels of a structurally modified, activated form of pp60c-src. Nature. 1985;316:554–557. doi: 10.1038/316554a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Onofri F, et al. Synapsin I interacts with c-Src and stimulates its tyrosine kinase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:12168–12173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.12168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brody DL, Yue DT. Relief of G-protein inhibition of calcium channels and short-term synaptic facilitation in cultured hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:889–898. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-03-00889.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altier C, et al. ORL1 receptor-mediated internalization of N-type calcium channels. Nat. Neurosci. 2006;9:31–40. doi: 10.1038/nn1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rane SG, Dunlap K. Kinase C activator 1,2-oleoylacetylglycerol attenuates voltage-dependent calcium current in sensory neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1986;83:184–188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.1.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tombler E, et al. G protein-induced trafficking of voltage-dependent calcium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:1827–1839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508829200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richman RW, et al. N-type Ca2+ channels as scaffold proteins in the assembly of signaling molecules for GABAB receptor effects. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:24649–24658. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312182200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lipscombe D, Raingo J. Internalizing channels: a mechanism to control pain? Nat. Neurosci. 2006;9:8–10. doi: 10.1038/nn0106-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonifacino JS, Traub LM. Signals for sorting of transmembrane proteins to endosomes and lysosomes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2003;72:395–447. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roche KW, et al. Molecular determinants of NMDA receptor internalization. Nat. Neurosci. 2001;4:794–802. doi: 10.1038/90498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin Z, Haus S, Edgerton J, Lipscombe D. Identification of functionally distinct isoforms of the N-type Ca2+ channel in rat sympathetic ganglia and brain. Neuron. 1997;18:153–166. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin Y, McDonough SI, Lipscombe D. Alternative splicing in the voltage-sensing region of N-type CaV2.2 channels modulates channel kinetics. J. Neurophysiol. 2004;92:2820–2830. doi: 10.1152/jn.00048.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thaler C, Gray AC, Lipscombe D. Cumulative inactivation of N-type CaV2.2 calcium channels modified by alternative splicing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:5675–5679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0303402101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roussel RR, Brodeur SR, Shalloway D, Laudano AP. Selective binding of activated pp60c-src by an immobilized synthetic phosphopeptide modeled on the carboxyl terminus of pp60c-src. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:10696–10700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.