Abstract

Two very rare conditions, ileosigmoid knot and intra-abdominal mucormycosis, occurred sequentially in a middle-aged HIV positive male.

At laparotomy for peritonitis, a gangrenous sigmoid volvulus with ileosigmoid knot was resected; 2 days later, colo-rectal continuity was restored, the distal ileum stapled and an end jejunostomy fashioned.

At re-laparotomy on day 15, necrotic stomach and spleen required a total gastrectomy and splenectomy. At reoperation 2 days later, a bile leak at the oesophago-jejunostomy site was repaired. Despite this intervention he continued to deteriorate and died of multiple organ failure 4 days later.

BACKGROUND

Two very rare conditions, ileosigmoid knot and intra-abdominal mucormycosis, occurred in a patient who was HIV positive. We discuss management dilemmas posed by this lethal combination.

CASE PRESENTATION

A middle-aged, non-diabetic male was admitted with a 24-hour history of abdominal pain, distension, vomiting and obstipation. On examination he was acutely ill and had peritonitis.

INVESTIGATIONS

Abdominal x rays showed dilated loops of small bowel and multiple air-fluid levels, but no free air. His blood tests showed a white blood count of 15 × 103/μL, a Hb 15.5 g/dL, normal electrolytes and creatinine, a venous CO2 18.7 mmol/L, a international normalised ratio of 1.6, a pH of 7.3, with a Base excess of –5. His HIV test was positive and total lymphocyte count was 0.34 × 103/μL.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

A diagnosis of small bowel obstruction with gangrenous bowel was made and after fluid resuscitation the patient was taken for emergency laparotomy.

TREATMENT

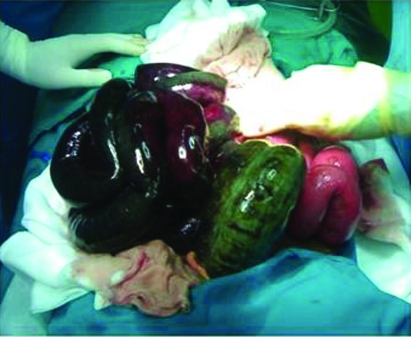

Intraoperative pathological findings were confined to the colon and small bowel. There was a gangrenous ileosigmoid knot shown in fig 1. The gangrenous bowel was resected without untwisting. About 80 cm of proximal small bowel remained. As the patient was unstable the ends of the small bowel and colon were tied off. Two days later at reoperation, colo-rectal continuity was restored, the distal ileum stapled and an end jejunostomy fashioned. His albumin was 7 g/L and he was started on intravenous nutritional support.

Figure 1.

Operative findings of the necrotic small bowel and sigmoid colon.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient had a wound dehiscence on day 15 and at re-laparotomy he was found to have necrotic proximal stomach and spleen with a large retroperitoneal abscess collection. A total gastrectomy and splenectomy was performed with an oesophago-jejunostomy reconstruction. A naso-jejunal feeding tube was inserted. Two days later a significant bile leak was noted in the abdominal drain. At reoperation an anastomotic leak from the oesophago-jejunostomy site was repaired. Despite this intervention he continued to deteriorate and developed multiple organ failure and died 4 days later.

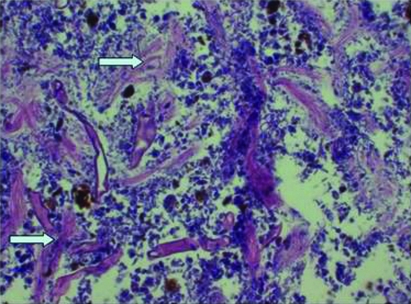

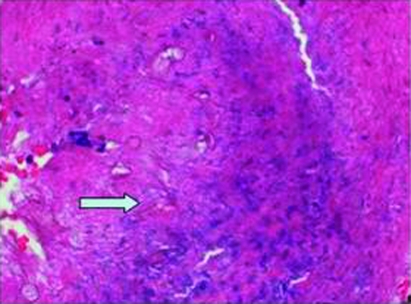

Small bowel and sigmoid colon histology showed typical features of gangrenous bowel with areas of haemorrhage, transmural necrosis and peritonitis. Stomach and spleen histology showed extensive necrotising inflammation with haemorrhage, peritonitis and vasculitic changes. Figure 2 and 3 show several branching (non-septate hyphae) organisms consistent with mucormycosis.

Figure 2.

Stomach histology and H&E stain showing necrotic background with distorted hypheal forms with large organisms (arrow).

Figure 3.

Spleen histology: arterial wall showing the organisms on H&E stain (arrow).

DISCUSSION

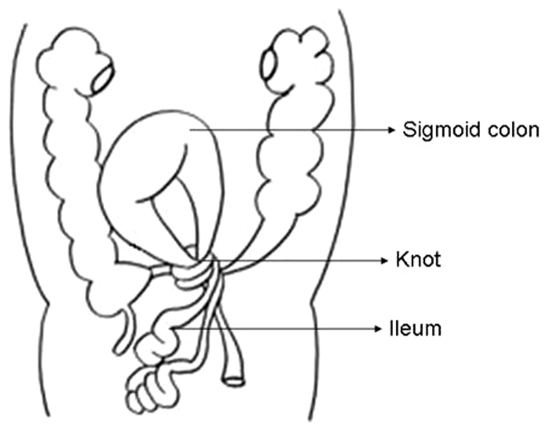

Ileosigmoid knot or compound volvulus is a rare but serious cause of intestinal obstruction. It is characterised by double-loop obstruction with both loops often found to be gangrenous. It is most frequently seen in males in their forties but is also well documented in children.1 Though rare, this entity is more common in developing countries like Africa and Asia than in developed countries. The frequency of ileosigmoid knot in tropical countries has been reported to account for as high as 15–25% of sigmoid colon obstructions. The condition is initiated by loops of ileum wrapping around the base of a redundant sigmoid loop shown schematically in fig 4. This is the most common type (type IA) found in about 47% of cases and it was the finding in our case.2

Figure 4.

Anatomic relationship of colon and small bowel.

Pre-operative diagnosis of ileosigmoid knot is difficult due to the rarity and the non-specific radiological findings. It is usually diagnosed during exploratory laparotomy for acute bowel obstruction. It is the rapid progression of double-loop obstruction leading to gangrene, which produces the clinical picture of hypovolaemic shock, acidosis, endotoxaemia and peritonitis. Mortality rate of ileosigmoid knot ranges from 19% to 47% due to the systemic effects of the gangrenous bowel. A short period of aggressive resuscitation followed by prompt surgery to relieve the obstruction with postoperative organ support are the key elements in reducing the morbidity and mortality.

If the general condition allows, the non-viable sigmoid and ileum are best resected and anastomosed.3 In unstable patients, damage control without the creation of stomas or restoring intestinal continuity has the potential to allow physiological restoration before progressing to more definitive surgery. This was the case in this instance and was effective in the short term allowing more definitive surgery at the second operation.

The surprising diagnosis of mucormycosis was made on the histology from the resected specimen on the day 15 re-laparotomy. Mucormycosis is an opportunistic fungal infection caused by the order Mucorals, class Zygomycetes. They most commonly cause infection in immunocompromised states, particularly diabetic ketoacidosis, severe malnutrition, haematological malignancies with neutropenia, organ transplantation and in patients with HIV/AIDS.4 Rhinocerebral infections account for more than half of the cases and are common in diabetics. Pulmonary and disseminated forms are seen with haematological malignancies. Gastrointestinal tract infections account for only 7% of cases and primarily found in patients suffering from extreme malnutrition. The stomach is the most frequently involved site (67%), but only 25% of cases are diagnosed antemortem. Gastric mucormycosis can be categorised into three forms: colonisation, infiltration and vascular invasive. The invasive form has a very high mortality. Antifungal treatment is often delayed because the diagnosis is only revealed after the histological examination and its bearing on the outcome in severe gastrointestinal mucormycosis is unclear.5,6

Disseminated mucormycosis although extremely rare is usually fatal. It is felt that mucor enters the respiratory tract, invades the lung and embolises to the brain, spleen and heart. We postulate that our patient already had gastric colonisation with the mucor. The dormant mucor became invasive in the stomach, after the acute physiological insult and extensive surgery, and progressed to disseminated mucormycosis as evidenced by the splenic involvement. Our index patient was not diabetic, he was acidotic from ischaemic bowel, he was not neutropenic but rather he was neutrophilic. His HIV status was known only when he was admitted to the intensive care unit second time after the re-laparotomy. His CD4 count was not done and he was not on any antiretroviral treatment. He was severely malnourished, documented by significant weight loss and emaciation with temporal wasting, which was supported by very low serum albumin and lymphocytes counts.

Post-mortem examination was not done and we do not know whether his lungs were colonised, but his transverse and dissecting colon had dusky looking areas, which were suggestive of invasiveness although these parts of the colon were not resected.

Management of mucormycosis is rapid correction of the predisposing factors if possible, surgical debridement of necrotic tissues and antifungal treatment with amphotericin B. Adjunctive treatment with hyperbaric oxygen, granulocyte colony stimulating factor and granulocyte transfusion have been used to some effect.

In our patient, gangrene associated with ileosigmoid knot necessitated laparotomy and extensive resection; the critical illness coupled with severe malnutrition and the immune compromised state resulted in the previously unreported co-pathology of invasive mucormycosis. Although correct management was instituted, the combined sequential factors of acute physiological insult, massive resectional surgery, immunocompromised states and disseminated mucormycosis resulted in the ultimate death of the patient.

LEARNING POINTS

Ileosigmoid knot should be resected without reduction.

Staged restoration of continuity is appropriate in critically ill patients.

Immunocompromised patients can manifest severe concomitant infections.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atamanalp S, Oren D, Yildirgan M, et al. Ileosigmoid knotting in children: a review of 9 cases. World J Surg 2007; 31: 31–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atamanalp SS, Oren D, Basoglu M, et al. Ileosigmoid knotting: outcome in 63 patients. Dis Colon Rectum 2004; 47: 906–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bawa D, Ikenna EC, Ugwu BT. Ileosigmoid knotting: a case for primary anastomosis. Niger J Med 2008; 17: 115–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiva PBN, Shenoy A, Nataraj KS. Primary gastrointestinal mucormycosis in an immunocompetent person. J Postgrad Med 2008; 54: 211–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomson SR, Bade PG, Taams M, et al. Gastrointestinal mucormycosis. Br J Surg 1991; 78: 952–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taams M, Bade PG, Thomson SR. Post-traumatic abdominal mucormycosis. Injury 1992; 23: 390–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]