Abstract

Infective endocarditis caused by Streptococcus bovis is known to be associated with colorectal malignancy. Other less common streptococci, specifically Streptococcus sanguis, can be similarly associated with gastrointestinal carcinoma. We present a case of disseminated colorectal carcinoma occurring after a confirmed S sanguis endocarditis, that required mitral valve surgery. There may be a need for gastrointestinal surveillance in patients presenting with bacteraemia caused by less common streptococci.

Background

Infective endocarditis caused by Streptococcus bovis is known to be associated with colorectal malignancy.1 Less well known is that other streptococci, specifically Streptococcus sanguis, can be similarly associated with gastrointestinal carcinoma.2 This case suggests the need for gastrointestinal surveillance in patients presenting with endocarditis and bacteraemia caused by less common streptococci. Gastrointestinal lesions may be found at an earlier stage, potentially improving prognosis.

Case presentation

A 56-year-old man was admitted with a 1 week history of fevers, anorexia and night sweats in May 2006. Bilateral splinter haemorrhages were noted and a pan-systolic murmur was heard at the apex. There was no evidence of hepatosplenomegaly. Three sets of blood cultures grew S sanguis and transthoracic echocardiography demonstrated thickened mitral valve cusps with posterior leaflet prolapse and moderate mitral regurgitation. Transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE) showed several small vegetations attached to, but moving independently of, the mitral leaflet (fig 1). Four weeks of intravenous antibiotics (benzylpenicillin, with 2 weeks of gentamicin) were given with a further 2 week course of oral antibiotics. The fever resolved and the white cell count and C reactive protein value returned to normal. Repeated blood cultures were negative. Assessment of the oral cavity revealed minor gingival inflammation with peri-apical radiolucency of a single tooth, which was removed under antibiotic cover. It was felt this was the source of the S sanguis. Repeat TOE after completion of antibiotics showed no resolution of the vegetations and demonstrated chord rupture and severe mitral regurgitation.

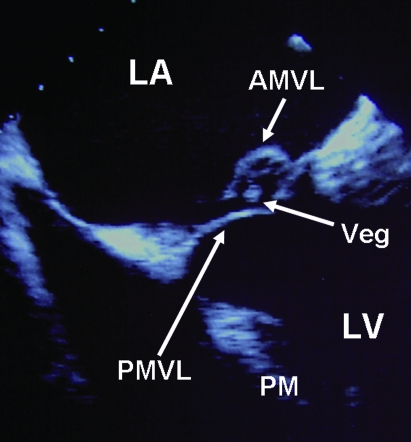

Figure 1.

Transoesophageal echocardiographic view showing a highly mobile vegetation suspended from a flail segment of the posterior mitral valve leaflet which prolapses back into the left atrium. Significant mitral regurgitation was evident on both colour flow and spectral Doppler imaging. AMVL, anterior mitral valve leaflet; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; PMVL, posterior mitral valve leaflet; PM, papillary muscle; Veg, vegetation.

While the mitral regurgitation was asymptomatic, the patient was referred for mitral valve repair on prognostic grounds. Preoperative coronary angiography was normal but confirmed severe mitral regurgitation on ventriculography. Surgical repair of the mitral valve repair was uneventful. No active endocarditis was seen, but ruptured chords of the P2 leaflet with mild A2 prolapse were noted to have contributed to the severe mitral regurgitation. Histological assessment confirmed signs of recent infective endocarditis, although no bacteria were grown on culture.

The patient re-presented 33 months later with night sweats, weight loss, malaise and lethargy. There had been no change in bowel habit. He had no family history of malignancy. He was a life-long non-smoker, ate a vegetarian diet, and was of normal weight. On examination, conjunctival pallor was noted and a liver edge was palpable. No splinter haemorrhages were seen and rectal examination was normal. A microcytic anaemia was found (haemoglobin 8.5 g/dl, normal range (NR) 13.0–18.0 g/dl; mean corpuscular volume (MCV) 75.4 fl, NR 80–98 fl), C reactive protein was 50 mg/, and white cell count was normal. Blood cultures were negative. Echocardiography showed an immobile posterior mitral valve leaflet and evidence of the previous mitral valve repair, but no endocarditis. Computed tomography of the abdomen showed a thickened hepatic flexure with enlarged lymph nodes in the para-aortic region. Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy was normal. Colonoscopy revealed a circumferential hepatic flexure tumour (fig 2) lesion. Biopsy confirmed infiltrating adenocarcinoma. Right hemicolectomy was performed and a staging assessment demonstrated extensive disease (C1 T4 N2 Mx). Adjuvant chemotherapy (oxaliplatin and capecitabine) was offered. Despite aggressive management, liver and lung metastases developed and the patient died of progressive malignancy 39 months after the initial endocarditis.

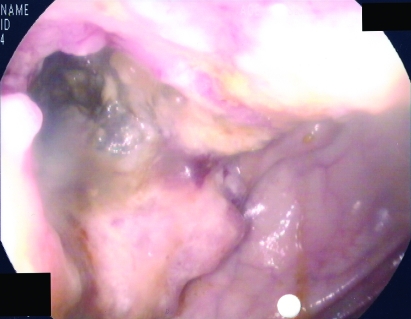

Figure 2.

Endoscopy image showing a circumferential tumour at the hepatic flexure.

Discussion

Endocarditis is an important disease with a median incidence of 3.6/100000 population, male preponderance (2:1), and an in-hospital mortality rate of 16%.3 Streptococcus viridans is one of the most common causes of native valve infective endocarditis.4 S bovis, a commensal in the lower colon, is strongly associated with colonic malignancy and adenomas.5 It is estimated that 20–80% of cases of S bovis endocarditis will have a bowel lesion and bowel screening is advocated.6 The incidence of extra-colonic malignancies, including pancreatic adenocarcinoma, may also be increased.6 In contrast, patients with known colon carcinoma have a 3–6% incidence of developing S bovis endocarditis.5

While the S bovis link to bowel lesions is well established, there is evidence that other forms of streptococcal infection are associated with colonic malignancy, including S viridans, S sanguis, S equinus and S agalactiae.2,7 Our case describes an association between S sanguis and transverse colon malignancy.

S sanguis, an α-haemolytic Gram positive coccus, is normally resident within gingival crevices and occasionally in the gastrointestinal tract.8 It is implicated in endocarditis after dental work or in severe periodontal disease. It rarely causes positive blood cultures but may do so in chronic respiratory or oropharyngeal conditions.8

Five previous reports suggest an association between S sanguis bacteraemia and colorectal malignancy.2,8–11 In these cases, endocarditis was not demonstrated on echocardiography. It is presumed that S sanguis entered the blood via ulcerated bowel lesions. The majority of cases featured elderly female patients with well differentiated adenocarcinomas in either the sigmoid or caecum. Based on previous reports, the time interval between bacteraemia and discovery of the colonic neoplasm ranged from days7 to 28 months12 following S bovis endocarditis.

The bacteraemia represents a marker of the occult malignancy; the streptococci are low grade pathogens and bacteraemia suggests an opportunistic change from their usual state. An ulcerating colonic malignancy may allow the bacteria to penetrate the bloodstream with subsequent endocarditis. Intact local polyps with metaplasia may allow bacterial translocation across a weakened protective wall. Animal work in rat models has suggested extracted antigens from S bovis may cause carcinoma,13 raising the possibility of an aetiological role for the bacteria.

It remains possible that the colonic lesion in our patient is a coincidental event. The patient was found to have mild gingival inflammation, potentially being the portal for the endocarditis with coincidental later malignancy. However, given the previously reported cases, some with long intervals between infection and malignancy, it is equally possible there is a true association between the two events.

Together with the previous descriptions, this report suggests that patients with confirmed streptococcal endocarditis, particularly caused by unusual subspecies, should undergo colonic assessment. However, it remains unclear how long surveillance should continue for, given that colonic malignancy may develop at a later period. While there is no formal guidance, a strong clinical suspicion of occult malignancy is recommended for both S bovis and S sanguis endocarditis.

Learning points

Several case reports have suggested different streptococcal bacteraemia can be associated with gastrointestinal malignancy. While S bovis is commonly considered, S sanguis has also been implicated.

S sanguis bacteraemia may be a consequence of an ulcerated gastrointestinal lesion and this may present later as a malignancy.

Investigation of the gastrointestinal tract should be considered in cases of S sanguis bacteraemia.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.McCoy WC, Mason JM. Enterococcal endocarditis associated with carcinoma of the sigmoid. J Med Assoc State Ala 1951; 21: 162–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marinella MA. Streptococcus sanguis bacteremia associated with cecal carcinoma: case report and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol 1997; 92: 1541–2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prendergast BD. The changing face of infective endocarditis. Heart 2006; 92: 879–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mylonakis E, Calderwood SB. Infective Endocarditis in Adults. N Engl J Med 2001; 345: 1318–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waisberg J, Matheus Cde O, Pimenta J. Infectious endocarditis from Streptococcus bovis associated with colonic carcinoma: case report and literature review. Arq Gastroenterol 2002; 39: 177–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gold JS, Bayar S, Salem RR. Association of Streptococcus bovis bacteremia with colonic neoplasia and extracolonic malignancy. Arch Surg 2004; 139: 760–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin CY, Chao PC, Hong GJ, et al. Infective endocarditis from Streptococcus viridans associated with colonic carcinoma: a case report. J Card Surg 2008; 23: 263–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macaluso A, Simmang C, Anthony T. Streptococcus sanguis bacteremia and colorectal cancer. South Med J 1998; 91: 206–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fass R, Alim A, Kaunitz JD. Adenocarcinoma of the colon presenting as Streptococcus sanguis bacteremia. Am J Gastroenterol 1995; 90: 1343–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kampe CE, Vovan T, Alim A, et al. Streptococcus sanguis bacteremia and colorectal cancer: a case report. Med Pediatr Oncol 1995; 24: 67–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siegert CE, Overbosch D. Adenocarcinoma of the colon presenting as Streptococcus sanguis bacteremia. Am J Gastroenterol 1995; 90: 1528–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robbins N, Klein RS. Carcinoma of the colon 2 years after endocarditis due to Streptococcus bovis. Am J Gastroenterol 1983; 78: 162–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biarc J, Nguyen IS, Pini A, et al. Carcinogenic properties of proteins with pro-inflammatory activity from Streptococcus infantariusc (formerly S. bovis). Carcinogenesis 2004; 25: 1477–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]