Abstract

Salmonella meningitis is an unusual complication of Salmonella sepsis that occurs almost exclusively in infants and young children. Cases that do occur in adults are associated with a high morbidity and mortality. The present study concerns a rare case of Salmonella meningitis, the first to be reported in Qatar, in a previously healthy young adult man who was admitted with fever, headache and nuchal rigidity. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) culture produced Salmonella paratyphi A, although cultures of blood were negative. The patient was admitted to the medical intensive care unit (MICU) and assisted with mechanical ventilation for 1 week, then transferred to the medical ward where he exhibited progressive improvement on treatment with meropenam for 3 weeks. The patient was found to have an incidental schwannoma causing right-sided hydronephrosis, and hydroureter, treated with double J stent insertion. He was discharged in good condition without any neurological sequelae.

BACKGROUND

Salmonella meningitis is a rare cause of meningitis in adult and carries high morbidity and mortality. Despite many complications, our patient was successfully treated and discharged without any sequelae. This case features the incidental finding of a rare pelvic schwannoma.

Salmonella are motile non-sporulating Gram-negative bacilli that infect or colonize a wide range of mammalian hosts. In humans, infection commonly causes gastroenteritis and enteric fever. Salmonella is one of the leading causes of food-borne diarrhoea in the developed world, and is responsible for 31% of food-related deaths in the USA.1

Salmonella infection in humans can cause four recognized forms of infections, including enteric (68%), Salmonella sepsis (8%), non-enteric focal infections (7%, including meningitis 0.8%) and a chronic carrier state (15%).2 When Salmonella bacteria enter the bloodstream, all tissues and organs are susceptible, leading to focal Salmonella infections such as abscesses, osteomyelitis, mycotic aneurysms, septic arthritis, pneumonia, endocarditis and meningitis. These focal infections are rare, and most commonly seen in patients who are immunocompromised . Even among patients who are immunocompetent , risk factors for non-enteric Salmonella can often be identified; for example, urinary tract infections occur more frequently in patients with urolithiasis, structural abnormalities, or concurrent renal infections (eg, renal tuberculosis), and Salmonella pneumonia or empyema typically occur in patients with chronic medical conditions such as malignancy, diabetes, chronic glucocorticoid use and sickle-cell disease.3,4

Gram-negative meningitis was first recognized and reported in 1892. Spontaneous Gram-negative meningitis is usually community acquired (two-thirds of cases in one series), and most frequently occurs in older patients or those who have underlying conditions such as alcohol-induced cirrhosis, diabetes, malignancy or splenectomy, or patients on glucocorticoid therapy.

Other cases in adults might be nosocomial or secondary to trauma or neurosurgery.5–7

Salmonella species account for more than 50% of the Gram-negative enteric organisms isolated from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).8 Salmonella meningitis is an unusual complication of salmonella sepsis and occurs almost exclusively in infants and young children.9 The central nervous system-related symptoms account for 5% to 35% of patients in one report.10 CSF studies are usually normal or reveal a mild pleocytosis, even in patients with neuropsychiatric symptoms.5

The response of Salmonella meningitis to conventional therapy including chloramphenicol and/or ampicillin is slow; complications arise frequently and mortality rates of 60% to 80% are common.8

We present a rare case of Salmonella meningitis with a positive CSF culture in an immunocompetent adult discovered to be a chronic carrier for hepatitis B virus with an incidental schwannoma, who recovered completely without any neurological sequalae.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 20-year-old man presented with a 5-day history of fever and severe headache associated with neck pain, chills and repeated vomiting. He had no convulsions, skin rash, contact with any ill persons, high-risk sexual exposure, significant past medical history, was on no regular medications and did not drink alcohol. Three days prior to his presentation he attended a private clinic and received an unidentified oral medication that produced no response.

On arrival he looked ill but was conscious and oriented with Glasgow coma scale of 15/15, nuchal rigidity, positive Kerning sign and no focal neurological deficit; temperature was 39.3°C, heart rate 130 beats/min, blood pressure 100/60 mm Hg, respiratory rate 20 breaths/min and O2 saturation 95% on room air. He had no skin rash, petechiae or purpuric lesions. Bibasal coarse crackles were heard on auscultation of the chest. Abdominal examination revealed a palpable liver and a palpable soft, painless mass (7×6 cm) in the suprapubic region and the left iliac fossa. The rest of the examination was unremarkable.

On the third day of hospitalisation he developed breathlessness with desaturation (O2 saturation 81% on room air), hypotension (98/52 mm Hg) and signs of circulatory hypoperfusion with bilateral pedal oedema. Abdominal examination revealed distension with minimal ascites. He was admitted to the medical intensive care unit (MICU) where mechanical ventilation was started and a central venous line was inserted.

On admission to the MICU his haemoglobin had dropped to 9.2 g/dl with a low platelet count of 73×103, prolonged prothrombin time 70.9 s and activated partial thromboplastin time 157.8 s, elevated D-dimer 1233 μg/litre, fibrinogen 5.3 g/litre, lactic acid 2.78 mmol/litre, creatinine kinase 232 U/litre, creatine kinase-muscle/brain (CK-MB) 7.28 ng/ml. serum myoglobin 372 ng/ml; arterial blood gas pH 7.22, pCO2 63.9 mm Hg, pO2 55.8 mm Hg, HCO3 26.1 mmol/litre.

Abdominal and pelvic ultrasound showed minimal ascites with a cystic mass (8×8 cm) posterior to the urinary bladder and marked right-sided hydronephrosis, hydroureter and an enlarged liver (17.6 cm span). A CT scan of the chest showed widespread incomplete consolidation over both lung fields with small bilateral pleural effusions. An abdominal CT scan showed a heterogeneously enhancing cystic mass 9×7.3 cm anterior to the sacrum (between S2 and S3), with moderate pelvic fluid, causing pressure and consequent dilatation of the collecting system of the right kidney with marked hydroureter and hydronephrosis (fig 1). Ascitic fluid was minimal and cultures of the transudate produced neither bacterial nor fungal growth.

Figure 1.

The kidney, ureter, bladder (KUB) film shows the right double J stent to relive the hydronehrosis and hydroureter.

A hepatitis viral screen was positive for hepatitis B surface antigen, IgG hepatitis B core antibodies and hepatitis B e antibodies; HIV and hepatitis C virus screens were negative. Stool examination for occult blood was repeatedly negative and the anaemia work-up was unremarkable. Thyroid hormonal assay and cortisol level were normal. Gastric lavages and endotracheal tube secretion (taken three times) were repeatedly negative for acid-fast bacilli (AFB).

A CT-guided fine needle aspiration of the pelvic mass, followed by tissue biopsy showed a spindle cell tumour consistent with schwannoma.

INVESTIGATIONS

Initial laboratory tests showed, peripheral white blood cell (WBC) count 30.5×103/μl with 88% neutrophils; Hb 11.1 g/dl with normal platelet count, normochromic normocytic anaemia with toxic granulation and a mild shift to the left, normal prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time; elevated alanine transaminase (ALT) 177 U/litre, aspartate transaminase (AST) 116 U/litre, alkaline phosphatase 437 U/litre, total protein 55 g/litre, serum albumin 22 g/litre.

The CSF was turbid and contained glucose 2.7 mmol/litre (concomitant blood sugar of 7.24 mmol/litre), protein 1.94 g/litre, total leukocyte count 60 cell/μl, predominantly neutrophils.

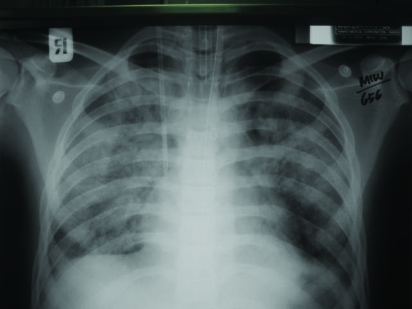

A computed tomography scan of the brain was normal. Chest x ray showed a bilateral basal infiltrate (fig 2). An echocardiogram (ECG) was normal apart from sinus tachycardia.

Figure 2.

Chest x ray showing bilateral patchy infiltration suggestive of pneumonia.

Culture of the CSF produced a growth of type A Salmonella paratyphi but repeated blood cultures were negative. Urine analysis showed RBC (3+) and a trace of albumin but no bacterial growth. Stool culture was negative for Salmonella, Shigella, campylobacter and Clostridium difficile A and B toxins. Salmonella antibody titre was positive only for S paratyphi A (1:2560).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Other causes of meningitis.

TREATMENT

The patient was treated empirically for bacterial meningitis with ceftriaxone and vancomycin for the first 3 days, then changed to meropenam after receiving the results of the CSF culture.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient was treated successfully with meropenam, and on day 8 of hospitalisation he was extubated. The urinary obstruction was relieved temporarily by insertion of a double J stent, and the patient was scheduled for later surgical removal of the pelvic schwannoma after recovery from his acute illness. He was discharged home after 28 days in a satisfactory condition with clinical and laboratory improvement.

DISCUSSION

Gram negative bacilli are an uncommon aetiology of community acquired meningitis in adults.11 They account for only 0.7% to 3.6% of cases in two different reports from The Netherlands12 and the USA.13 Salmonella meningitis is an unusual complication of Salmonella sepsis; accounting for 0.8% to 6% of all cases of bacterial meningitis.14–16 The first reported case of Salmonella meningitis was made by Gohn in 1907.17

Salmonella meningitis is a rare complication in adults associated with high morbidity and mortality and has been reported mainly in those with sickle-cell anaemia, AIDS, lymphoma, acute leukaemia,18–20 other immune system-compromising conditions and those patients receiving corticosteroids;21 however, our patient was previously healthy and has no reported underlying diseases.

There is a higher incidence of bacteraemia (75% to 100%) in patients who are immunocompromised compared to 1% to 4% in patients who are immunocompetent;22 additionally, the disease tends not to respond to antibiotics and/or reoccurs with the discontinuation of the therapy.23

The CNS-related symptoms account for 5% to 35% of patients in one report.10 However, headache and myalgia occur in 90%, stupor and delirium are present in 40% to 70% and neck rigidity is seen in 10% of the patients.21

In another large study, 95% of patients who presented with bacterial meningitis had at least two out of four of the following symptoms: headache, fever, neck stiffness and altered mental status; however, only 44% have the classic triad of fever, neck stiffness and altered mental status.24

Our patient presented with classical symptoms of fever, headache and neck stiffness but later he developed altered mental status on his third day of hospitalisation.

Although lumbar puncture usually normal or disclose mild pleocytosis.21 The CSF of our patient was purulent and the culture was positive for S paratyphi A, while his negative blood culture may be attributed to the probable empirical antibiotic used by the patient before his presentation. Lumbar puncture was negative 6 days after starting meropenam.

Pulmonary manifestations occur only in 1% of the patients with enteric fever. Mild cough with sticky sputum is the earliest symptoms in a study of 360 cases reported by Stuart and Roscoe. Bronchitis occurred in 85% and pneumonia in 11% of the patients. Non-specific chest x ray abnormalities were observed in 25% of the patients with pulmonary symptoms. Salmonella organisms were rarely found in the sputum.21 Our patient developed a productive cough with bilateral pulmonary infiltrate consistent with pneumonia, but his sputum culture was repeatedly negative. We believe that his pneumonia is part of Salmonella complications, as he responded to treatment with clinical and radiological improvement. Adult respiratory distress syndrome may be another possibility secondary to sepsis.

Typhoid fever is often associated with abnormal liver enzymes, but severe hepatic involvement with a clinical feature of acute hepatitis is a rare complication.

Clinical jaundice in Salmonella hepatitis usually occurs within the first 2 weeks of the febrile illness. Hepatomegaly and moderate elevation of transaminase levels are common findings. A positive culture for Salmonella from blood or stool is essential to differentiate Salmonella hepatitis from other causes of acute hepatitis.

Regarding our patient, we think that elevated liver enzymes is secondary to sepsis rather than specific Salmonella hepatitis as his blood and stool culture were negative and the patient showed a remarkable response to treatment of the underlying infection with recovery of his liver enzymes. Although his hepatitis serology markers are suggestive of chronic carrier state, it was not possible to diagnose him with chronic hepatitis without clinical stigmata of chronic liver disease and definite liver biopsy.

Schwannoma was just an incidental finding and had no relation to his present illness, apart from the pressure symptoms causing hydronephrosis and hydroureter. The pelvic and retroperitoneal location is uncommon, and accounts only for (0.5% to 12%) of all retroperitoneal tumours, which makes our case one of the more interesting to be reported. Although his structural abnormality makes him at a higher risk for Salmonella urosepsis, this has been excluded by repeatedly negative urine analysis and culture. The patient was assessed thoroughly by a urologist, the obstruction temporarily released by double J stent, and the patient was scheduled for surgical removal of the pelvic schwannoma at a later date.

The response to conventional therapy (chloramphenicol and ampicillin) is poor and the mortality rate is higher among patients treated with antibiotics because of bacterial resistance to ampicillin, chloramphenicol and cotrimaxozole; therefore the third generation cephalosporin is considered the first choice.25–34

Because of different patterns of antibiotic resistant among Salmonella species,35–39 antibiotic susceptibility studies for each isolate should determine the drug of choice. Our patient was successfully treated with meropenam according to the result of CSF culture and antibiotics susceptibility.

Cases of Salmonella meningitis in adults are associated with high morbidity and mortality, reaching 94% in one study.9 In 1979, Kauffmann and St Hilaire40 reported a mortality rate of 71.4% in their series of 14 adult patients with Salmonella meningitis.

Mortality is highest for patients with a profound disturbance of consciousness.10 Of those who do survive, 43% are left with permanent neurological deficits. Although ventriculitis, subdural empyema, hydrocephalus and very rarely brain abscess are recognised acute neurological complications of Salmonella meningitis,41 our patient did not develop any of these complications.

Prolonged therapy for Salmonella meningitis is indicated in view of slow response and high possibility of relapse, which might approximate 64% of cases.41

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends treatment of Salmonella meningitis for 4 weeks or 3 weeks after sterile CSF culture.42 Our patient ran a complicated course of symptoms; however, he was successfully treated with meropenam for 3 weeks after sterilisation of his CSF culture, and discharged home without any neurological sequelae.

LEARNING POINTS

Although Salmonella meningitis is a rare cause of meningitis, it still can occur even in patients who are immunocompetent.

The diagnosis of Salmonella meningitis needs a high index of suspicion.

Although Salmonella meningitis is associated with high morbidity an mortality rates, early diagnosis and aggressive treatment can save the patient’s life and minimise complication risk.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mead PS, Slutsker L, Dietz V, et al. Food-related illness and death in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis 1999; 5: 607–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saphra J, Winter JW. Clinical manifestations of salmonellosis in man: an evaluation of 7779 human infections identified at the New York Salmonella Center. N Engl J Med 1957; 256: 1128–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lesser C, Miller SI.Salmonellosis.:Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, et al., eds. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine, 16th edn New York, USA: McGraw-Hill, 2005: 897–902 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen JI, Bartlett JA, Corey GR. Extra-intestinal manifestations of Salmonella infections. Medicine (Baltimore) 1987; 66: 349–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berk SL, McCabe WR. Meningitis caused by Gram-negative bacilli. Ann Intern Med 1980; 93: 253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahal JJ, Simberkoff MS. Host defense and antimicrobial therapy in adult Gram-negative bacillary meningitis. Ann Intern Med 1982; 96: 468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu CH, Chang WN, Chuang YC, et al. The prognostic factors of adult Gram-negative bacillary meningitis. J Hosp Infect 1998; 40: 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryan JP, Scheld WM. Therapy of experimental meningitis due to Salmonella enteritidis. Antimicrob agents chemother 1992; 36: 949–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Denis F, Badiane S, Chiron JP, et al. Salmonella meningitis in infants. Lancet 1977; 1: 9–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uysl H, Karademir A, Kilinic M, et al. Salmonella encephalopathy with seizure and frontal intermittent rhythmic delta activity. Infection 2001; 29: 103–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolff MA, Young CL, Ramphal R. Antibiotic therapy for Enterobacter meningitis: a retrospective review of 13 episodes and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis 1993; 16: 772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van de Beek D, de Gans J, Spanjaard L, et al. Clinical features and prognostic factors in adults with bacterial meningitis. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Durand ML, Calderwood SB, Weber DJ, et al. Acute bacterial meningitis in adults. A review of 493 episodes. N Engl J Med 1993; 328: 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henderson LL. Salmonella meningitis: report of three cases and review of 144 cases from the literature. Am J Dis Child 1948; 75: 371–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barclay N. High frequeny of Salmonella species as a cause of neonatal meningitis in Ibadan, Nigeria. Acta Paediatar Scand 1971; 60: 540–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osuntotokun BO, Bademosi O, Ogunremi K, et al. Neuropsyghiatric manifestations of typhoid fever in 959 patients. Arch Neurol 1972; 27: 7–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghon J. Bericht uber den XIV Internationalen Knogress fur Hygiene und Demographie [in German]. Berlin 1907; 4: 21–3 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heineman HS, Janes WN, Cooper WM, et al. Hodgkin’s disease and Salmonella typhimurium infection. JAMA 1964; 188: 632–34 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolfe MS, Louria DB, Armstrong D, et al. Salmonellosis in patients with neoplastic diseases. A review of 100 episodes at Memorial Cancer Center over a 13 year period. Arch Intern Med 1971; 128: 546–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cherubin CE, Fodor T, Denmark LI, et al. Symptoms, septicemia and death in salmonellosis. Am J Epidemiol 1969; 90: 285–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stuart B, Roscoe P. Typhoid clinical analysis of 360 cases. Arch Intern Med 1946; 78: 629–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cherubin CE, Marr JS, Sierra MS, et al. Listeria and Gram negative meningitis in NYC 1972–1979. Am J Med 1981; 71: 199–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacobs JL, Gold JW, Murray HW, et al. Salmonella infection in acquired immune deficiency sundrome. Ann Intern Med 1985; 102: 186–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schuchat A, Robinson K, Wenger JD, et al. Bacterial meningitis in the United States in 1995. N Engl J Med 1997; 337: 970–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheubin CE, Corrado ML, Nair SR, et al. Treatment of Gram negative bacillary meningitis: role of the new cephalosporin antibiotics. Rev Infect Dis 1982; 4: 453–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bryan JP, Soheld WP. Therapeutic evaluation of experimental Salmonella enteritidis meningitis (M). Abstract from the 24th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Washington DC, 1984. Washington DC, USA: American Society for Microbiology, 1984 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kinsella TR, Yoger R, Shulman ST, et al. Treatment of Salmonella meningitis and brain abscess with the new cephalosporins: two case reports and a review of the literature. Ped Inf Dis J 1987; 6: 476–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olarte J, Galindo E. Salmonella typhi resistant to chloramphenicol, ampecillin, and other antimicrobial agents. Strain isolated during an extensive typhoid fever epidemic in Mexico. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1973; 4: 597–601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chhina RS, Gupta BK, Wander GS, et al. Chloramphenicol resistant Salmonella meningitis in adults. A report of three cases. J Assoc Physicians India 1993; 41: 535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ward LR, Rowe B, Threlfall EJ. Incidence of trimethoprim resistance in Salmonella isolated in Britain: a twelve year study. Lancet 1982; 2: 705–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hadfield TL, Monson MH, Wachsmuth JK. An outbreak of antibiotic resistant Salmonella enteriditis in Liberia. West Africa J Inf Dis 1985; 151: 790–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rowe B, Ward LR, Threlfall EJ. Spread of multi resistant Salmonella typhi. Lancet 1990; 36: 1065–6 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zavala I, Barrera E, Nava A. Ceftriaxone in the treatment of bacterial meningitis in adults. Chemotherapy 1988; 34(Suppl 1): 47–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCracken GH, Jr, Threlkeld N, Mize S, et al. Moxalactam therapy for neonatal meningitis due to Gram-negative enteric bacilli: a prospective controlled evaluation. JAMA 1984; 252: 1427–32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sirinavin S, Chiemchanya S, Visudhipan P, et al. Cefuroxime treatment of bacterial meningitis in infants and children. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1984; 25: 273–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith MD, Duong NM, Hoa NTT, et al. Comparison of ofloxacin and ceftriaxone for short-course treatment of enteric fever. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1994; 381: 716–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wallace MR, Yousif AA, Mahroos GA, et al. Ciprofloxacin versus ceftriaxone in the treatment of multiresistant typhoid fever. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1993; 12: 907–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhat KG, Andrade AT, Karadesai SG, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Salmonella typhi to quinolones and cephalosporins. Indian J Med Res 1998; 107: 247–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhutta ZA, Khan IA, Shadmani M. Failure of short-course ceftriaxone chemotherapy for multi-drug resistant typhoid fever in children: a randomized controlled trial in Pakistan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2000; 37: 1572–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kauffman CA, St Hilaire RJ. Salmonella meningitis: occurrence in an adult. Arch Neurol 1979; 36: 578–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.West SE, Goodkin R, Kaplan A. Neonatal Salmonella meningitis complicated by cerebral abscesses. 1977; 127: 142–5 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases Salmonella infection. : Peter G, ed. Report of the committee on infectious diseases, 25th edn Elk Grove Village, Illinois, USA: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2000 [Google Scholar]