Abstract

Multiple lung abscesses are extremely rare in healthy children. We report a case of polymicrobial bilateral lung abscess in a 9-month-old previously well infant presenting with a short history of fever and respiratory distress. The management options and outcome are discussed.

Background

Lung abscess is an infrequent but serious paediatric problem.1 Children with congenital or acquired immunodeficiency are particularly prone to the development of lung abscess.2 Literary evidence for bilateral lung abscesses in healthy, non-immunocompromised children is mostly in the form of isolated case reports or small case series.1,3–5 Most of these cases have underlying congenital or chronic medical disorders. We hereby report the occurrence of bilateral lung abscesses in a 9-month-old previously well infant.

Case presentation

A previously healthy developmentally normal, appropriately immunised 9-month-old male infant from an average socioeconomic background presented with complaints of cough and fever for 5 days. There was dry cough with high spiking intermittent fever but no nasal discharge, poor feeding or lethargy. He was admitted to a local hospital and treated with intravenous ceftriaxone for 3 days and oxygen before referral to our institute for persisting symptoms.

At admission, the infant was febrile, had tachycardia (heart rate 122/min), tachypnoea (respiratory rate 48/min) with laboured breathing, saturation of 94% in room air, mild intercostal and subcostal recessions, and bilateral wheeze. He was lethargic with poor oral acceptance. The rest of the systemic examination was within normal limits.

Investigations

Investigations done at admission revealed haemoglobin of 10 g/dl, total leucocyte count (TLC) of 10.2×109/l with 55% neutrophils, and platelet count of 203×109/l. Serum electrolytes, liver function tests and renal function tests were within normal limits. The chest x-ray (posterioanterior view) was normal.

At day 4 of admission, TLC increased to 20.1×109/l with neutrophilic leucocytosis. C reactive protein (CRP) of 16.8 mg/dl (normal range 0.6–6 mg/dl) was documented and the chest x-ray showed bilateral pleural effusions with no other significant signs or findings.

Pleurocentesis was suggestive of an exudative effusion (glucose 78 mg/dl, protein 5.2 g/dl, lactate dehydrogenase 712 IU/l, leucocytes 1100 per high power field with >90% lymphocytes). The pleural fluid and blood cultures remained sterile.

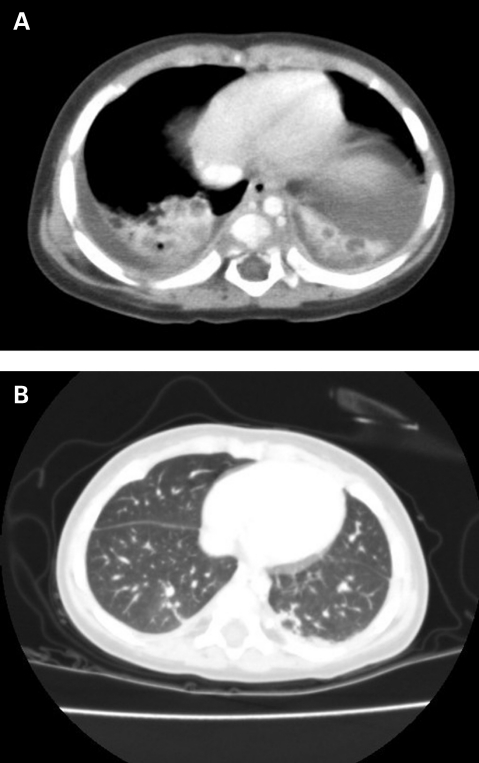

The respiratory distress persisted without significant radiological findings on chest x-ray apart from minimal effusions. A contrast enhanced chest computed tomography (CT) scan was done on day 10 of hospital stay. It showed collapse and consolidation in both lower lobes with multiple well defined cavitating lesions (fig 1A). There was bilateral pleural effusion and necrotic lymph nodes in the right supraclavicular region. CT guided aspiration of the right lower lobe lesion revealed thick pus which on culture grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Klebsiella pneumoniae sensitive to clindamycin, meropenem and ciprofloxacin.

Figure 1.

(A) Section of computed tomography (CT) scan of chest showing bilateral lung abscesses. (B) Section from follow-up CT scan of chest showing complete healing of abscesses and normal lung parenchyma.

In view of multiple lung abscesses, the history was reviewed and the child was investigated further. There was no history of delayed cord fall at birth, consanguinity, regurgitation of feeds or foreign body aspiration. Mantoux test was negative; immunoglobulin levels were normal and ELISA for HIV 1 and 2 was negative. Mutation analysis performed for cystic fibrosis for common mutations in India was non-contributory.

Treatment

With a clinical diagnosis of bronchiolitis, the infant was started on supportive treatment. After an initial clinical improvement, the child had recurrence of fever and worsening of respiratory distress requiring increments in oxygen support on day 4 of admission. Thereafter intravenous antibiotics (amoxicillin+clavulanic acid and amikacin) were added. Vancomycin was started on day 5. These were continued until day 12 of admission. On day 10, CT guided aspiration of the right lower lobe lung abscess was performed. On day 13 of hospital stay, clindamycin, meropenem and ciprofloxacin were given as per the sensitivity pattern of Klebsiella and Pseudomonas species. These were continued for 2 weeks where after oral antibiotics were continued for another 2 weeks.

Outcome and follow-up

A steady improvement was observed after CT guided aspiration as fever defervesced rapidly and respiratory distress subsided. Chest x-ray after 18 days of treatment showed no new shadows, with small residual right sided pleural effusion. At discharge, the child was afebrile, active and feeding well. A follow-up CT scan at 6 months showed complete healing of abscesses with normal lung parenchyma (fig 1B). The child is thriving well and is asymptomatic.

Discussion

With the advent of modern antibiotic treatment, the incidence of lung abscess has decreased notably.1 However, when anatomical and physiological barriers against acid reflux and aspiration are compromised by neurodevelopmental, gastrointestinal, and immunological disorders, lung abscess can ensue.1,5,6 Despite thorough clinical evaluation and extensive investigations, no underlying pathogenetic factor or comorbid condition contributing to the occurrence of bilateral lung abscesses could be identified in the index patient. Aspiration, though difficult to exclude, is unlikely to cause multiple and bilateral lesions.7

The most common organisms causing lung abscess in children include Staphylococcus aureus followed by Streptococcus pneumoniae and in cases of suspected aspiration, Gram-negative organisms and anaerobes.5,8 Pseudomonas is extremely unlikely to cause primary lung abscess, especially in patients without immunosuppression or an underlying chronic illness such as cystic fibrosis.8,9 The index patient developed bilateral polymicrobial (Pseudomonas and Klebsiella) lung abscesses.

Most investigators have observed that aggressive management should be reserved for those patients in whom fever persists more than 1 week despite appropriate treatment or who deteriorate clinically and develop complications such as empyema or bronchogenic spread.7,8 However, the type of treatment remains controversial. Pneumonostomy and catheter drainage, resection of the abscess and, recently, transtracheal aspiration and drainage has been reported to be useful.8 Children with a lung abscess, both primary and secondary, have a significantly better prognosis than adults with the same condition.8 We managed our patient conservatively with antibiotics after a diagnostic aspiration of the lesion with good response. Smaller, multiple lesions and a constitutionally stable young infant made us decide against a more aggressive therapeutic approach.

Learning points

The serial chest x-rays done in our case did not identify the lesions which were picked up only on the CT scan. The lesions were in the basal parts of both lower lobes and would have probably been picked up on lateral chest x-ray, which is not obtained in the portable images routinely done in paediatric critical care units.

To the best of our knowledge, polymicrobial bilateral lung abscess manifesting at 9 months of age in a previously well infant without prior surgical intervention has not been previously reported.

In conclusion, awareness of this entity, appropriate investigations to rule out secondary causes, with expeditious action to obtain microbiological proof and prompt institution of appropriate treatment, are mandatory to ensure optimum outcome.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yen CC, Tang RB, Chen SJ, et al. Pediatric lung abscess: a retrospective review of 23 cases. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2004; 37: 45–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kosloske AN, Ball WS, Jr, Butler C, et al. Drainage of pediatric lung abscess by cough, catheter, or complete resection. J Pediatr Surg 1986; 21: 596–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amaya RA, Baker CJ. Bilateral lung abscesses in an adolescent. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis 2002; 13: 71, 142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zaputowycz O, Williams FA, Arthur A. Bilateral lung abscess associated with a severe masticator space infection. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1986; 61: 327–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pei CC, Li MH, Ping SW, et al. Clinical management and outcome of childhood lung abscesses. J Microbiol Innunol infect 2005; 38: 183–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carrascosa M, Pérez-Castrillón JL, Sampedro I, et al. Lung abscess due to Streptococcus mitis: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis 1994; 19: 781–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moreira JD, Camargo JJD, Felicetti JC, et al. Lung abscess: analysis of 252 consecutive cases diagnosed between 1968 and 2004. J Bras Pneumol 2006; 32: 136–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patradoon-Ho, Fitzgerald D. Lung abscess in children. Paediatric Respiratory Reviews 2007; 8: 77–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang CC, Chang LY, Lu CY, et al. Bilateral lung abscesses due to pseudomonas aeruginosa infection after open heart surgery in an infant: report of one case. Acta Paediatr Taiwan 2005; 46: 370–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]